AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 4

In this issue, we sit down with artist, Malik Roberts, who relates the experience of creating one of the few African American artworks to sit permanently in the Vatican collection. Fashion designer, Prajjé Oscar John-Baptiste introduces his latest collection — an ode to Haiti, and its goddesses. We head to South Carolina to experience the Gullah-inspired music of Ranky Tanky. And in New York, we watch a new world being born with photographer and journalist, Naeem Douglass, who takes us inside the city’s Black Lives Matter protests, and economist Janelle Jones, who reminds us in these times that we are the economy. We are thrilled to share our cover with chef and musician, Lazarus Lynch. Inside, we talk with him about his cookbook, Son of a Southern Chef and his new album, I’m Gay. From a house tour in Brooklyn to a travel piece in Tobago, this issue takes you all over the Diaspora. And we see how of the concept of Diaspora was first introduced in a look back at how Pan-Africanism led the way to how we think of international Blackness today. It is a showcase of our culture, our creativity, our resilience, and our diversity, our demands for the present and our hopes for the future. Welcome to our summer issue.

In this issue, we sit down with artist, Malik Roberts, who relates the experience of creating one of the few African American artworks to sit permanently in the Vatican collection. Fashion designer, Prajjé Oscar John-Baptiste introduces his latest collection — an ode to Haiti, and its goddesses. We head to South Carolina to experience the Gullah-inspired music of Ranky Tanky. And in New York, we watch a new world being born with photographer and journalist, Naeem Douglass, who takes us inside the city’s Black Lives Matter protests, and economist Janelle Jones, who reminds us in these times that we are the economy.

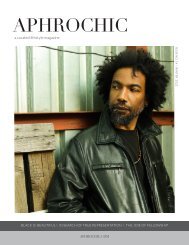

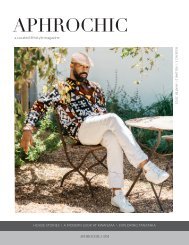

We are thrilled to share our cover with chef and musician, Lazarus Lynch. Inside, we talk with him about his cookbook, Son of a Southern Chef and his new album, I’m Gay.

From a house tour in Brooklyn to a travel piece in Tobago, this issue takes you all over the Diaspora. And we see how of the concept of Diaspora was first introduced in a look back at how Pan-Africanism led the way to how we think of international Blackness today. It is a showcase of our culture, our creativity, our resilience, and our diversity, our demands for the present and our hopes for the future. Welcome to our summer issue.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 4 \ VOLUME 1 \ SUMMER 2020<br />

RENAISSANCE MAN \ FREEDOM SUMMER \ TOBAGO IN COLOR<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

SLEEP ORGANIC<br />

Avocado organic certified mattresses are handmade in sunny Los Angeles using the finest natural<br />

latex, wool and cotton from our own farms. With trusted organic, non-toxic, ethical and ecological<br />

certifications, our products are as good for the planet as they are for you. Shop online for fast<br />

contact-free delivery. Start your organic mattress trial at AvocadoGreenMattress.com

We took this photo back in February, during a trip to Wilmington, <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina. We didn’t<br />

know it would be our only trip to the beach this year. Back then we imagined that the year<br />

ahead would be full of adventure, travel, and new directions for the magazine. But suddenly<br />

the world changed and all of those things were gone.<br />

Our world is changing in profound ways. What seemed relevant even a few months ago, is almost hard to remember<br />

today. Every two weeks, or sometimes two days, it feels like we wake up in a new reality. News of the virus is replaced by news<br />

of how many Black people are being killed by the virus. That news is replaced by how many Black people are being killed by<br />

the police, the virus, and the rush to reopen.<br />

Somewhere in the middle of mourning all that we have lost this year — including a grandmother — our perspective<br />

changed. We began to see the opportunities in the crisis, the clear lens that this catastrophe has offered on a broken society.<br />

This clarity was demonstrated when people who’d never felt anguish over seeing a Black life extinguished on video before,<br />

joined the fight to ensure they’d never see it again. It extends to an economy designed for the richest alone and a government<br />

that would rather use taxpayer money to break protests than to provide safety and stability for taxpayers during a health<br />

emergency. And it reminds us, a people strengthened by a culture forged in hardships, saved by music and the DJs that play<br />

it, comforted by food traditions begun by people in bondage, inspired by elders, that these times have come and gone before<br />

— and we have remained.<br />

Our fourth issue is a celebration of the new world we are all entering. One that is intersectional, inclusive, just, and<br />

focused on a full acknowledgment of the undeniable valuable of Black life. In this issue, we sit down with artist Malik Roberts,<br />

who relates the experience of creating one of the few African American artworks to sit permanently in the Vatican collection.<br />

Fashion designer, Prajjé Oscar John-Baptiste introduces his latest collection — an ode to Haiti and its goddesses. We head to<br />

South Carolina to experience the Gullah-inspired music of Ranky Tanky. And in New York, we watch a new world being born<br />

with photographer and journalist Naeem Douglass, who takes us inside the city’s Black Lives Matter protests, and economist<br />

Janelle Jones, who reminds us in these times that we are the economy.<br />

We are thrilled to share our cover with chef and musician Lazarus Lynch. Inside, we talk with him about his cookbook,<br />

Son of a Southern Chef and his new album, I’m Gay. In a moment where the intersections matter more than ever, Lynch’s<br />

multi-hyphenate talents and spirit of Black Gay Pride are exactly what the world needs right now.<br />

From a house tour in Brooklyn to a travel piece in Tobago, this issue takes you all over the Diaspora. And we see how the<br />

concept of Diaspora was first introduced in a look back at how Pan-Africanism led the way to how we think of international<br />

Blackness today. It is a showcase of our culture, our creativity, our resilience, and our diversity, our demands for the present<br />

and our hopes for the future. Welcome to our summer issue.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter<br />

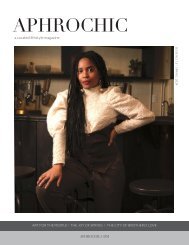

With the amazing Danielle Brooks<br />

Photo: Chinasa Cooper

SUMMER 2020<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Visual Cues 14<br />

It’s a Family Affair 16<br />

Mood 24<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // A Spirit of Duality 28<br />

Interior Design // Brooklyn Dreamscape 36<br />

Culture // Freedom Summer 60<br />

Food // Renaissance Man 78<br />

Travel // Tobago in Color 84<br />

Wellness // Plant Life 98<br />

Reference // The Emergence of Diaspora 102<br />

Sounds // Ranky Tanky 106<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 110<br />

The Remix 116<br />

Hot Topic 120<br />

Who Are You? 122

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

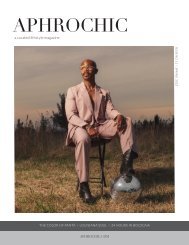

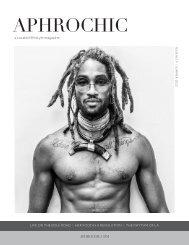

Cover photo: Lazarus Lynch by Anisha Sisodia<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Brooklyn, NY<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

info@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors (left to right below):<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

Janelle Jones<br />

David A. Land<br />

Tedecia Wint<br />

issue four 9

READ THIS<br />

Summer is so important to the book trade that summer reading lists always start appearing in early<br />

May, offering ideas for beach reads and lazy days. But this is a summer like no other. With a pandemic,<br />

economic instability, and worldwide protests for racial equality, light summer fiction seems to belong<br />

to another era. But with great change comes great opportunity; in revolution there is evolution. Our<br />

expanded reading list in this issue both celebrates Black culture and illuminates where we’ve been, and<br />

where we are headed.<br />

Misty Copeland<br />

By Gregg Delman<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli. $39.95<br />

My Brother Moochie<br />

By Issac J. Bailey<br />

Publisher: Other Press. $25.95<br />

City/Game: Basketball in New York<br />

Edited by William C. Rhoden<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli. $45<br />

10 aphrochic<br />

serenaandlily.com

READ THIS<br />

Meals, Music, and Muses<br />

By Alexander Smalls<br />

Publisher: Flatiron Books. $25<br />

The Third Reconstruction<br />

By The Reverend Dr.<br />

William J. Barber II<br />

Publisher: Beacon. $25<br />

River Hymns<br />

Poetry by Tyree Daye<br />

Publisher: Copper<br />

Canyon Press. $23<br />

Wild Interiors<br />

By Hilton Carter<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli. $24.95<br />

12 aphrochic

VISUAL CUES<br />

The U Street corridor in <strong>No</strong>rthwest Washington, DC, could almost be a model for what happens to a<br />

neighborhood when gentrification moves in. Once known as Black Broadway, home to thriving Black-owned<br />

businesses in the early 20th century, U Street is now filled with the same chain stores and restaurants<br />

that you might find on any other nameless road in any other city. But an intrepid group of students has<br />

launched a project to showcase and celebrate U Street’s history and impact. Led by Georgetown University<br />

professor Ananya Chakravarti and students from both Georgetown and Howard University, the project is<br />

creating a digital bank of photos, archives, and oral histories about U Street’s past. “It’s a layered history,”<br />

says Chakravarti. “The community became really interested in the project, and are invested in it, which<br />

means so much.” The kickoff for the project, held in <strong>No</strong>vember 2019, featured events in 16 U Street venues<br />

over two days, including neighborhood trivia with Dr. Bernie Demczuk at Ben’s Chili Bowl, an iconic<br />

restaurant that has been a pillar on the street since 1958. The students have just finished an app – with<br />

work slowed by the pandemic and shutdown – that offers as a comprehensive digital library to celebrate<br />

not only U Street, but Black history in the nation’s capital. If you have photos or an oral history of U Street<br />

that you would like to share, contact Ananya Chakravarti at ac1646@georgetown.edu. To learn more, go<br />

to www.rememberingyoudc.org.<br />

14 aphrochic issue four 15

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

A Refuge<br />

One of the more interesting functions that my family house has served over the years has been that of a<br />

refuge for members of my family as they made the transition from one stage of life to another. My Uncle<br />

Allen — my grandmother’s brother — lived there for several months after leaving the Air Force. My<br />

uncle Rodney did, too, having served in the Air Force as well. Other family members came and went for a<br />

multitude of reasons. More than once the change in circumstances came after a fire had claimed another<br />

home. For me, the house was my first home. I lived there for a year before my parents moved first into an<br />

apartment, then into the house that I grew up in.<br />

<strong>No</strong> matter where home was for me,<br />

“The House,” remained a constant, though<br />

it was much emptier by the time I arrived.<br />

In fact, for all of my life before 2005, the<br />

family home was just “Mom-Mom’s house,”<br />

to me. My grandmother lived in the home<br />

alone when I was a kid, and as the youngest<br />

grandchild I had no grasp of how long it<br />

had been in the family, how many of us had<br />

lived there, or what it had meant.<br />

It never occurred to me to wonder<br />

what it was like for her to live alone in a<br />

place that had once been full of so many<br />

people she loved. Whether it felt a little<br />

lonely or if she was grateful for the quiet<br />

wasn’t something she ever expressed to<br />

me. Had I thought to ask, I suspect her<br />

answer might’ve included a little of both.<br />

But whatever her answer might have been,<br />

it wasn’t a question I considered when my<br />

turn came to have the house (mostly) to<br />

myself.<br />

I moved into the house after college<br />

along with my brother Andre. By the time<br />

we took up residence, Mom-Mom, whose<br />

health was dwindling, had moved to live<br />

in my parent’s home. After years of dorm<br />

rooms and tiny apartments, it was good<br />

to have an entire house with what felt like<br />

massive spaces, more bedrooms than<br />

we needed, and one of the tiniest, most<br />

weirdly designed bathrooms either of us<br />

had ever seen.<br />

There’s a reason why real estate<br />

agents say that bathrooms and kitchens<br />

sell houses — it’s because in both cases,<br />

bad ones will seriously impact the experience<br />

of living there. This bathroom<br />

had survived the coming and going of<br />

many family members, but along the way<br />

it had developed both structural and<br />

aesthetic issues. The bathtub and shower<br />

were separate, the latter consisting of<br />

little more than a closet with an ill-fitting<br />

curtain that kept all of the light out<br />

but none of the water in. The sink was too<br />

small, and the toilet was crowded in by the<br />

massive radiator (painted an oppressive<br />

dark green) that actually dominated the<br />

space.<br />

On the aesthetic side, the bathroom<br />

had received a beautiful facelift about<br />

15 years before we moved in. Time had<br />

done its work on the very 1990s look,<br />

It‘s a Family Affair is an ongoing series<br />

focusing on the history of the Black family<br />

home, stories from the Harper family,<br />

and the renovations and restorations of a<br />

house that bonds this family.<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

and from Harper Family Archive<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Bryan Mason’s grandmother, “Mom-Mom,” Alice Harper<br />

16 aphrochic issue four 17

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

Bryan Mason‘s Uncle Allen, left.<br />

Allen with Bryan‘s maternal grandfather<br />

Leroy, below.<br />

The family home‘s bathroom, before the <strong>AphroChic</strong> renovation.<br />

18 aphrochic issue four 19

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

however, and by the time we were there the<br />

wallpaper was peeling, tiles were cracking,<br />

and pieces of the popcorn ceiling were frequently<br />

on the floor.<br />

It’s not that the bathroom made life<br />

there unbearable. I loved living with my<br />

brother, and 22-year-old men are rarely<br />

bothered by inconvenient bathroom architecture.<br />

But even then it was easy to see<br />

that there was room for improvement. So<br />

when the opportunity came, years later,<br />

to renovate certain parts of the home’s<br />

interior, there was one space that was definitely<br />

at the top of my mind.<br />

Smart renovation is about picking<br />

your battles, and even then there are some<br />

you win and some you lose. For us, that<br />

meant accepting that there was a lot about<br />

the bathroom’s structure that we couldn’t<br />

change. There wasn’t time or money, for<br />

example, to bring the bathtub and shower<br />

together. In fact, just changing the bathtub<br />

would prove a nearly impossible task. After<br />

starting the project we quickly learned<br />

that not only was the cast iron tub original<br />

to the house, but it had actually been built<br />

into the structure of the home in a way that<br />

made it impossible to remove in one piece.<br />

The solution was a sledge hammer and a lot<br />

of work for my brother-in-law Will.<br />

For this iteration of the bathroom,<br />

we wanted to create something with a<br />

more timeless feel. We simplified the<br />

color palette to a classic black and white,<br />

expressed together in the large, dazzling<br />

patterned tiles that replaced the earlier<br />

speckled pink versions. As the centerpiece<br />

of the room, we placed a larger vanity with<br />

a marble top and black base that worked<br />

with the lines of the new bathtub and toilet<br />

to give the room a more modern feel.<br />

Though Mom-Mom never got to see<br />

the bathroom’s redesign, we thought a<br />

lot about her when bringing it to life. The<br />

house was not just a refuge for those on<br />

their way to something new. Mom-Mom<br />

was young when the family first moved<br />

into the house. She raised her daughter<br />

and her grandchildren there. It was open<br />

to everyone who needed it and when the<br />

time came, she passed it on. It was her<br />

house. We wanted to honor that by creating<br />

a calm and relaxing space she would have<br />

enjoyed. Hopefully it will last for as many<br />

years, and offer as much comfort to the<br />

family members who are there now and<br />

those who will be there next. AC<br />

20 aphrochic issue four 21

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

“Though<br />

Mom-Mom<br />

never got<br />

to see the<br />

bathroom’s<br />

redesign, we<br />

thought a lot<br />

about her<br />

when bringing<br />

it to life.”<br />

22 aphrochic issue four 23

MOOD<br />

Caribbean Queen<br />

The Beanie Man and Bounty Killer Verzuz battle was<br />

Blas One Piece $300<br />

May Two Piece $230<br />

Hama Two Piece $275<br />

maygelcoronel.com<br />

legendary. Even among the explosion of live social media<br />

events in the last few months, this virtual concert stands<br />

out for its huge reception. It was a moment for fans of<br />

all kinds – DJs, dancehall queens, and hype men alike –<br />

to honor the Jamaican cultural phenomenon that has<br />

influenced music around the globe. You can bring a bit<br />

of that same energy into your space with a few fresh and<br />

Oroo Natural Tote $210<br />

aaksonline.com<br />

modern pieces that bring the queens of dancehall to your<br />

dining table, pre-Colombian weaves to your outdoor<br />

retreat, and woven pieces that reflect the colors of the<br />

amazing Caribbean sea.<br />

Lisa Braided Tassel<br />

Earrings $85<br />

lillianandjoan.com<br />

La Perla II Armless $299<br />

jaimeluisorganic.com<br />

Sisters Lumbar $159<br />

aphrochic.com<br />

Dancehall Queen Salt and Pepper<br />

Shakers by BAUGHaus Design Studio<br />

$55 per pair<br />

baughausdesign.com<br />

Woven Necklace Pendant Lighting<br />

in Cobalt $485<br />

54kibo.com<br />

24 aphrochic issue four 25

FEATURES<br />

A Spirit of Duality | Brooklyn Dreamscape | Freedom Summer |<br />

Renaissance Man | Tobago in Color | Plant Life | The Emergence<br />

of Diaspora | Ranky Tanky

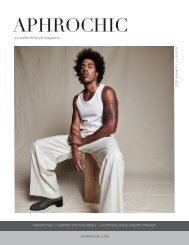

Fashion<br />

A Spirit<br />

of Duality<br />

It is a tale of two sisters. One, the Rada Loa, Erzulie<br />

Fréda Dahomey, is the goddess of love, beauty,<br />

jewelry, dancing, and flowers. The other is Erzulie<br />

Dantor, most senior of the Petro Loa and goddess of<br />

motherhood, credited as the spiritual inspiration to<br />

Haiti’s famed revolution. Opposites in nature and<br />

rivals for the love of Ogun, the two are traditionally<br />

depicted as enemies. But for his SS20 collection,<br />

Haitian-born designer Prajjé Oscar Jean-Baptiste,<br />

painted a different story.<br />

Photos courtesy of Prajjé Oscar Jean-Baptiste<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

28 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

In Jean-Baptiste’s new vision, the goddesses are reconciled, working together to bring<br />

their people to freedom. Though their personalities may contrast, they work synergistically<br />

towards a common goal. In Prajjé Oscar’s ÈZILI collection, the legacy of these<br />

goddesses is celebrated beautifully. The designer worked extensively in his native<br />

country to acquaint himself with local manufacturers and techniques, determined to<br />

create a collection that would benefit the nation by being manufactured locally.<br />

Featuring an eye-catching palette, the collection is modern yet traditional, presenting a<br />

mix of ready-to-wear pieces and stunning couture gowns. Bold hues evoke the natural<br />

splendor of Haiti through beading and embroidery handmade by Haitian artisans. The<br />

most special piece of all - a hand-painted jacket. A work of art, made for the people,<br />

inspired by the gods. AC<br />

32 aphrochic

Fashion

Interior Design<br />

Brooklyn Dreamscape

Interior Design<br />

The Whimsical Home<br />

of Artist Paul Suepat<br />

The interior world of an artist is a dreamscape full of wonders — improbable tricks<br />

of physics that bend realities, alter perceptions, and open minds. To bring even a<br />

fraction of what he or she sees into reality, the artist labors for a lifetime. For it to<br />

ever be seen in full, the time, labor, and strain it would take to produce it would be<br />

nearly impossible to accommodate. Which is why, for the most part, it stays inside<br />

their heads — then there’s the house where Paul Suepat lives.<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

issue four 39

Interior Design<br />

For 17 years, Paul Suepat has made his<br />

home in the historic Stuyvesant Heights area<br />

of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, New York.<br />

The Jamaican-born artist has spent much of<br />

that time in an effort to map the interior of his<br />

mind onto the interior of his home. As a result,<br />

his expansive and beautifully designed brownstone<br />

is as much an art gallery as a home, showcasing<br />

Paul’s surrealist aesthetic while demonstrating<br />

the clear overlap that he feels exists<br />

between art and design.<br />

“I don’t want to be bored,” he muses,<br />

looking effortlessly Brooklyn in an outfit that<br />

pairs a vest and button-down shirt with well<br />

worn jeans, a broken-in “Camp Vibes” ball cap<br />

and meticulously maintained white sneakers.<br />

As we move through the house, his train of<br />

thought doesn’t so much move from topic to<br />

topic as from sentence to sentence as he looks<br />

for the combination of words that will best<br />

convey the meaning he wants to offer. “I’m very<br />

obsessed with art and design,” he adds quickly.<br />

“Growing up as a child I was really obsessed<br />

with art and design, so I created this whole kind<br />

of gallery that you can live in.” Looking around<br />

the amazing interior with its colors, oddities,<br />

and what seems like a million tiny details, it’s<br />

hard to imagine where boredom could hide.<br />

As an artist, Paul Suepat is a man driven<br />

by contrasts. Focused constantly on the<br />

nebulous space between ambiguity and definition,<br />

his art moves between sculpture and<br />

painting, whimsical figures and strong abstract<br />

shapes, specific emotions and imaginative<br />

contexts. Or perhaps the point is not so much<br />

the contrasts themselves, but creating an<br />

instance of connection between them, bridging<br />

the gap so that for the moment in time that the<br />

piece represents, “this” and “that” become indistinguishable.<br />

It’s a drive that fuels his design<br />

aesthetic as well as his artistic approach.<br />

“My design style and my art style are totally<br />

connected,” he reflects. “It’s one of those things<br />

where you can’t stop and say, ‘I’m doing art,’ or<br />

‘I’m doing design.’ I just do.”<br />

If someone were inclined to create their<br />

own private wonderland, they could hardly<br />

do better for a canvas than a brownstone in<br />

Bed-Stuy. The two-story home has spacious<br />

rooms, impossibly high ceilings, and impeccable<br />

architectural details, including crown<br />

moldings on just about every wall and every<br />

ceiling. To step in through the front door is to<br />

be greeted by the home’s classic entryway,<br />

complete with luxuriously tiled floors. The<br />

effect is stunning, but the real attractions start<br />

in the living room, which is just to the left.<br />

There are two things a guest is likely to<br />

notice about Paul Suepat’s living room shortly<br />

after they enter. The second is that it, like many<br />

of the other rooms in the house, is decorated<br />

to take full advantage of the terrific amount of<br />

natural light that the home receives. The first is<br />

that they entered the room between two beautifully<br />

crafted pillars — painted a bright, electrifying<br />

shade of blue.<br />

“I didn’t want to take it too seriously,”<br />

Paul says about his playfully-colored throughway.<br />

“Sometimes columns are so pretentious.<br />

So I said let’s play with it and put it in<br />

blue and just have fun.” Past the pillars, the<br />

living room is the first space in the home to<br />

give a full taste of Paul’s theory of contrasts,<br />

pairing mid-century modern classics with<br />

a surfboard-shaped coffee table and a chair<br />

painted in a screen-printed, rainbow camouflage.<br />

Paul explains his combinations, saying,<br />

“I think design is just design. Whether it’s old,<br />

it’s mid-century, it’s art-nouveau, it’s art-deco,<br />

it’s Memphis, it’s whatever it is. It’s all one.<br />

It’s good design. It’s just how you put them<br />

together and make them work. I have too many<br />

layers sometimes, and it’s about how I put<br />

them together.” But what really helps it all hang<br />

together is the fact that, visually, the furniture<br />

is really just an accessory to the art.<br />

Paul’s art is very patient. It’s surreal in<br />

a way that seems to make sense the first few<br />

times you walk past it, as it waits for you to<br />

take a closer look. For example, one could walk<br />

past the coffee table half a dozen times before<br />

realizing that there’s a six-pack of armed men<br />

sitting on it in a convenient carrying case<br />

42 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

marked “no deposit, no return.” Or that the<br />

beautiful painting of yellow flowers hanging<br />

over the loveseat is actually three-dimensional<br />

and thickly ribboned with texture. Or that<br />

in place of wood, the fireplace has only a small<br />

electric light with a neon filament spelling out,<br />

“lamp.” There’s no end to the details, and no<br />

standard on how long it takes to notice them.<br />

But once noticed they become irresistible,<br />

enticing you to stare and daring you to look for<br />

more.<br />

Past the living room, the dining room is<br />

Paul’s image of a dinner under the sea. One of<br />

the first contrasts to be bridged here is the one<br />

between form and function, as the lighting<br />

over the dining table is a work of art in itself,<br />

and the centerpiece of the concept. “I always<br />

had this vision of people kind of living in art —<br />

that art is around you — and so I wanted to have<br />

this fantasy dinner where art is everywhere.”<br />

Beginning with the idea of eating underwater<br />

with jellyfish all around, the light, which was<br />

originally a single jellyfish, became several.<br />

The form and function motif continues around<br />

the table as, capped by mid-century bentwood<br />

chairs at the head and foot, the seating along<br />

the sides is equipped with back rollers to<br />

keep guests comfortable as they sit and chat.<br />

Because dinner beneath the sea is pointless<br />

without any interesting creatures in attendance,<br />

another of the artist’s unique creations<br />

stands sentinel at the far end of the room. With<br />

only one of its two legs attached to the pedestal,<br />

the piece was originally intended as a commentary<br />

on balance. But when inspiration hit to<br />

use rolled foam to add a larger head, something<br />

new was born. It was the kind of spur-of-themoment<br />

creativity that Paul relies on to keep<br />

things interesting.<br />

“You have to take risks to make art,<br />

because sometimes it’s the accident that makes<br />

it great,” he says. “The first thing is to be open<br />

as an artist, open your mind to everything and<br />

look at everything, and be curious. Examine everything<br />

and pay attention to everything.” It’s<br />

this openness that allows space for all of the<br />

contrasts Paul builds into the decor of each<br />

room on a small level, and between rooms and<br />

floors on a larger scale. “I have a certain feel on<br />

one floor and a different feel on another. Every<br />

room is special to me in different ways.”<br />

Upstairs the decor takes a step away from<br />

the sublime and into the realm of memory.<br />

The library, one of Paul’s favorite spaces in the<br />

entire home, speaks specifically to the memory<br />

of his godparents. “The library came from my<br />

godparents, who I lived with when I first came<br />

to New York,” he remembers. “They were very<br />

kind of radical, political, very Black Panther<br />

kind of people. So when they passed away a<br />

couple of years ago, I decided that I wanted<br />

to remember them very, very much. So we<br />

literally took the library out of their house, bitby-bit,<br />

and we gently brought it all here and<br />

put it all together and recreated that room and<br />

the memory of them. That was really very, very<br />

important to me.”<br />

Memory plays a role in the bedroom as<br />

well. Amid the tropical colors and modern<br />

lines that define one of the home’s most resolutely<br />

contemporary spaces, one playfully<br />

designed art piece disguises a dresser as a stack<br />

of “Pablo” (Paul’s nickname) brand bananas.<br />

The piece is a call-back to both the bodegas he<br />

frequented after late nights of bartending in<br />

his early days in New York and to his childhood<br />

home in Kingston, Jamaica. This blending of<br />

memories is another feature common to both<br />

his art and his design.<br />

“I question my existence a lot,” he begins.<br />

“And so, I look back at my past to get some of<br />

why I do this, why am I attracted to texture,<br />

why am I attracted to the earth. I grew up in this<br />

area of Jamaica that had a lot of mango trees and<br />

cherry trees and plum trees, and that’s one of<br />

the things I miss most about the Caribbean …<br />

it’s like you literally can wallow in the nature,<br />

like it’s all over you. That’s more my aesthetic.<br />

It’s a mix of the nature of the Caribbean and the<br />

man-made of New York. And I kind of mix that<br />

together in a way, like blend it in a blender and<br />

just kind of spit it out.”<br />

The outdoor spaces behind the house are<br />

as much a fantasy as the rooms within it. The<br />

first is an enclosed dining area that combines<br />

modern seating with a table lined with an assortment<br />

of Paul’s sculpted characters. The<br />

enclosure is perfect for those days when the<br />

44 aphrochic

“You have to take risks<br />

to make art, because<br />

sometimes it’s the accident<br />

that makes it great.”<br />

issue four 47

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

artist wants to enjoy the outdoors, but the<br />

weather is not cooperating.<br />

Stairs from the enclosed dining room lead<br />

down to the home’s final surprise: a sculpture<br />

garden. Perhaps the most fantastic part of this<br />

fantasyland, the garden features wide open<br />

spaces replete with sculpted tables, planters<br />

and even oversized flowers.<br />

A final figure stands on a raised platform<br />

as the center of attention, between two chairs.<br />

It’s an oasis built to transport visitors far away<br />

from the city to a place where Cheshire cats and<br />

Mad Hatters might not be an unexpected sight.<br />

It would be hard for someone walking by<br />

to guess at the wonders that sit waiting inside<br />

Paul Suepat’s house, and that’s probably by<br />

design.<br />

The home itself represents a meeting of<br />

contrasts, the mundane world outside of it, and<br />

the dream world inside. But as always, the point<br />

is likely not to note the difference, but to make<br />

a connection. Inside and outside, textured and<br />

smooth, normal and abnormal, art and design<br />

— Paul is open to everything and receives it all<br />

in the same way. “It’s all the same thing. It’s fun.<br />

I laugh, I smile every day I look at it. And that’s<br />

what I like about coming home.”<br />

Paul Suepat is the founder of 2AC Space<br />

(www.2acspace.com), a gallery located in<br />

Brooklyn, New York. AC<br />

52 aphrochic issue four 53

Interior Design

58 aphrochic issue four 59

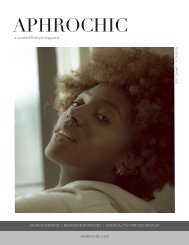

Culture<br />

Freedom<br />

Summer<br />

An <strong>AphroChic</strong> interview<br />

with Naeem Douglas, the<br />

Brookladelphian<br />

Interview by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by The Brookladelphian<br />

60 aphrochic issue four 61

The summer of 2020 marks an incredible moment in history, seeing the birth of one of the<br />

largest civil rights movements the world has ever known. After years of what seemed like an<br />

endless cycle of Black death and white apathy, something new has happened. Cries of support<br />

for Black lives have begun to come from places that were once deathly silent as the terrifying<br />

immunity with which the police could kill Black people was proven over and over, one video at<br />

at time. The outrage of a community used to suffering alone has been felt by others and together<br />

they are beginning to stand up, not in one city or one nation, but all over the world.<br />

The spirit of protest that promises to define this summer is<br />

about more than any one person or one community, and certainly<br />

more than one “bad apple.” This is about every community that<br />

has seen too many lost coming together to declare an end to a centuries-old<br />

system that will terrorize, oppress, and kill to ensure<br />

supremacy. It’s a constitutional right being asserted by people<br />

pushed too far by racist subjugation, economic exploitation, and governmental<br />

apathy, and who will no longer be silent.<br />

<strong>No</strong> matter how many words we throw at this historic moment,<br />

they’ll all fail to capture it: the weary grief of people so tired of<br />

grieving that there’s nothing left to do but explode; the sudden<br />

awakening of those abruptly coming to realize that nothing costs<br />

more than privilege and struggling to figure out what to do about<br />

it; the optimism of seeing so many voices calling out together for<br />

change; and the fear and outrage of those who champion the status<br />

quo as they see it come crumbling down around them. When a<br />

thousand words won’t begin scratch the surface, there’s only one<br />

thing to do: take a picture.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>: What inspired you to go out and capture what’s been<br />

happening around Black Lives Matter in New York?<br />

Naeem Douglas: The reaction to George Floyd’s death was<br />

unlike anything I’ve ever seen. It sounds absurd to say, but Black<br />

people dying at the hands of police is something this country has<br />

been okay with for a long time. This latest incident has seemed to<br />

wake up America. Black people aren’t the only ones upset. I wanted to<br />

document what was happening.<br />

AC: With a deadly pandemic going on, were you concerned<br />

about going out to march?<br />

ND: COVID-19 is definitely something I’m constantly thinking<br />

about. You probably can notice none of my photos are particularly<br />

close up. I try my best to stay out the fray but still take a photo. This<br />

is history in the streets and I felt compelled to document it. I COULD<br />

NOT STAY HOME.<br />

AC: What was the spirit of the people that you saw marching<br />

like? What was your own spirit like?<br />

ND: Good spirits, but you could also sense a bit of exhaustion<br />

from Black people. I think people really want police interactions with<br />

Black people to change. In the streets of New York City, there’s a lot of<br />

support for this movement. People honk their horns in support as the<br />

marches and protest move throughout New York City.<br />

AC: Was there anything in particular that surprised you about<br />

this moment?<br />

ND: I was certainly surprised by white people’s involvement. I<br />

covered many protests in the past going back to the Sean Bell protest.<br />

It’s mostly a Black affair. But I’ve seen so many white people involved<br />

in these recent protests. They’re not taking leadership roles but I’ve<br />

seen a few rallies that were 80% white.<br />

AC: There have been many reports of police violence against<br />

protestors here in the city. Did you witness any violence as you<br />

captured this movement?<br />

issue four 63

Entertaining

Culture<br />

ND: I did see some on the first day. The<br />

very first day of the protests I happened to<br />

be in [Manhattan] and was riding my bike by<br />

Foley Square and saw a rally. I always have a<br />

camera with me so I started to make some<br />

photos. Then the marchers started moving<br />

north and the police were not having it.<br />

They were really aggressive and definitely<br />

initiated contact. It escalated fairly quickly.<br />

It ended up being a little too much for<br />

me. So I broke off the march and tried to<br />

get myself situated. I was straddling my Citi<br />

Bike trying to put my phone away, load film<br />

in my camera and get a bearing on what was<br />

going on. I was about a block away from the<br />

protest. Suddenly I feel a tap on leg which<br />

turned into pounding. I looked up and saw<br />

a bicycle officer and he’s hitting my leg with<br />

his front wheel and yelling at me to move. It<br />

was so bizarre and unnerving. I was the only<br />

person on the street, between two parked<br />

cars and clearly just trying to put myself<br />

together. Before anything could really<br />

happen, his fellow officer pulled him away<br />

and he went back to the group.<br />

AC: What role can photography play in<br />

amplifying movements?<br />

ND: Photography is pivotal because<br />

one photograph can tell many stories. With<br />

video, you have a lot going on. However,<br />

a photograph is one moment in time. <strong>No</strong><br />

sound, no music, and in my case no color<br />

(I mostly shoot black and white film). One<br />

moment and one subject can sum up years<br />

of frustration, ignorance, exhaustion, etc.<br />

The simplicity of it is powerful to me. I’m<br />

reminded of the photo from the late 1950s<br />

of a Black student walking to school in<br />

Arkansas and you see these white women<br />

and students behind her screaming insults<br />

at her. That one moment captured the vitriol<br />

of racism during that time and the struggle<br />

for us to be treated like humans.<br />

AC: Which photographers have inspired<br />

your work?<br />

ND: I have to start with the greats,<br />

Gordon Parks and Jamel Shabazz. I would<br />

be remiss if I didn’t mention Ernest Withers,<br />

but his life as a FBI informant during the<br />

civil rights movement leaves me conflicted.<br />

I’m also a big fan of Andre Wagner, a Brooklyn-based<br />

photographer who’s doing incredible<br />

work.<br />

AC: Is there one moment or image that<br />

stands out in your mind?<br />

ND: One is a man praying at The<br />

Barclays Center. He’s so peaceful in his<br />

prayer. It moved me in the moment and<br />

when I saw the photo later. The second<br />

photo is of a young Black woman leading a<br />

march through Brooklyn. It was inspiring<br />

to see her putting her voice to the rally, so<br />

it was particularly moving to see her and be<br />

able to document it.<br />

AC: What do you hope will come out<br />

of this moment? Could we see real police<br />

reform, or something even bigger?<br />

ND: I hope a real change comes from<br />

this. America has had a hard time facing<br />

its original sin (slavery) and the effects it<br />

continues to have. This country definitely<br />

needs to address it in a meaningful way.<br />

Naeem Douglas is the Brookladephian, a photographer<br />

and journalist based in Brooklyn, NY.<br />

(www.naeemdouglas.com) AC<br />

66 aphrochic issue four 67

Culture

Culture

Culture

Culture<br />

“One moment and one subject<br />

can sum up years of frustration,<br />

ignorance, exhaustion. The<br />

simplicity of it is powerful to me.”<br />

74 aphrochic

Culture<br />

issue four 77

Food<br />

Renaissance<br />

Man<br />

Lazarus Lynch Is<br />

Freely Expressing<br />

Himself and We’re<br />

Here For It!<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos by Anisha Sisodia<br />

Styling by Keeon Mullins<br />

Assistant Styling by Windy Dias<br />

78 aphrochic

Food<br />

Lazarus Lynch is a rock star, a bona fide food star, an author and an all-around renaissance<br />

man. And this summer, the chef-singer-songwriter is on a roll. His bold and energetic<br />

cookbook, Son of a Southern Chef: Cook With Soul, continues to inspire those who are looking for<br />

new ways to bring soul food to life. And on Spotify his recent release, I’m Gay, is a self-professed<br />

Black Pride anthem, written and produced by Lynch himself. But before he was a multi-hyphenate<br />

artist with irons in just about every fire, Lazarus Lynch was a young boy from Jamaica,<br />

Queens, who grew up watching one of his favorite chefs make magic in the kitchen — his father,<br />

the renowned restaurateur Johnny Ray Lynch.<br />

To say that food was in Lazarus’s blood would be an understatement.<br />

His father was an inspiration to him from the start, but<br />

the family’s culinary roots ran even deeper. “[Dad] moved to New<br />

York when he was pretty young. All the recipes that he cooked for us<br />

growing up were inspirations from my grandmother Margaret Lynch,”<br />

he recalls. “He inherited that gene watching her as a kid and I started<br />

watching him. When my dad finally opened up Baby Sister’s Soul Food,<br />

I was like, ‘I really love this.’ I loved that my dad was cooking. I loved<br />

going to the restaurant and watching him, helping him.”<br />

The cooking lessons didn’t end when father and son left the<br />

restaurant. Food was part of the family dynamic, and played a role<br />

in just about everything they did. “Food was always central. It was a<br />

cultural thing. It was how we gathered. I grew up in the church. Every<br />

Sunday after service, there was dinner. Those dinners were shared<br />

and oftentimes we would make things and bring it to the church.”<br />

The next major turn in his food career came during high school,<br />

where Lazarus began to mix the art of cooking with the art of media.<br />

“I had four years in high school just really developing my skills as a<br />

chef,” he remembers. Lynch is a graduate of New York City’s Food<br />

and Finance High School, the city’s only culinary-focused public<br />

high school. The rich environment provided incredible opportunities<br />

to a young culinary mind, giving him access to coveted positions,<br />

including interning and working in the test kitchens of The Food<br />

Network, a brand he would later work for professionally.<br />

Lazarus’ own brand, Son of A Southern Chef, which he began<br />

in 2014, is an homage to his father, his way of continuing the legacy<br />

that his grandmother passed down. It’s also a culmination of all of the<br />

experiences that made food mean so much: the moments watching<br />

his father in the kitchen, Sunday dinners after church service, and<br />

gatherings with family were all translated into stunning dishes<br />

that mix beloved tradition with bold innovation. Dishes like his,<br />

Oh-My-Gah Green Beans with Crushed Peanuts, and Mother Soand-So’s<br />

Lemon Pound Cake are featured throughout his cookbook.<br />

A colorful, energetic tour of the chef’s philosophy of food and life,<br />

the book is a collection of dishes culled from family recipes, many<br />

which had only been passed down through stories or by watching and<br />

learning, as Lazarus often did. “In our community a lot of the things<br />

that are passed down are oratory, so nothing is documented. I started<br />

watching my dad cook and then I started taking notes. Literally<br />

notebooks of this is the potato salad, this is the macaroni and cheese.”<br />

Just a year after founding the brand, Lazarus’x father passed away<br />

from cancer. “I was able to sit down with my dad. He and I talked for<br />

several hours. I think he realized that I had a gift and that I was really<br />

passionate about food. He also saw that there were a lot of opportunities<br />

coming my way. It all was very exciting for him,” he reflects. “One<br />

of the things he said to me, which I’ll never forget, was I want [you] to<br />

take this to the next level. I’ve never forgotten it and it has been such<br />

a grounding place for me. Almost a mantra for me to continue doing<br />

80 aphrochic issue four 81

Food<br />

this work because it’s more than just the food and<br />

the recipes. It’s really about inspiring another generation<br />

to own your story.”<br />

The young food star has certainly taken things<br />

to the next level. A two-time champion of the series<br />

Chopped, Lazarus is also host of the Food Network’s<br />

digital series Comfort Nation. With several shows<br />

under his arm, and now a successful cookbook,<br />

Lazarus is diving deeper into another love — music.<br />

After finishing up his cookbook, Lynch decided<br />

it was time to get back to other forms of creativity,<br />

and took some time off to refocus his energy. It<br />

was during that time that he began writing music.<br />

Dozens of songs poured out of him, and by the end<br />

of 2019, just months after his book had launched, he<br />

was working on his first album. “The themes [are]<br />

around identity, self-expression, spirituality and<br />

allowing your spirit and your body to be the home<br />

for you.”<br />

The centerpiece of his growing catalog is the<br />

exploration of gay, Black male identity, I’m Gay.<br />

Equal parts emotional ballad and defiant anthem,<br />

the song is a conversation between Lazarus and<br />

his younger self that ends in a joyous declaration<br />

of self-acceptance, set against the backdrop of a<br />

church organ. “I’m gay,” he says simply. “It is an<br />

anthem. It is jubilant. It is a freedom song.”<br />

While music might seem like an unexpected<br />

turn in a burgeoning culinary career, it’s not at<br />

all surprising. For Lazarus, it’s all about authentic<br />

self-expression and creating work that helps him<br />

speak his truth, whether in food, music or whatever<br />

creative pursuit fits the moment and the emotion.<br />

“I feel that ingredients are like clothes. It’s like you<br />

go into a store, into a closet and it’s really about expressing<br />

how you feel. It’s like notes in music. The<br />

arrangement of those notes. The arrangement of<br />

those flavors. That’s all a form of expression,” he<br />

reflects. “Cooking techniques are the accessories<br />

— the glasses, the frames, a round toe versus a<br />

pointed toe. That’s how I think about food. What do<br />

i feel like creating? What are the accessories? And<br />

then ultimately how will it make me feel?” AC<br />

I’ve Been Drinking Watermelon Cocktails<br />

(inspired by Queen Bey)<br />

Serves 2<br />

Prep Time 5 minutes<br />

Total Time 10 minutes<br />

INGREDIENTS:<br />

2 teaspoons kosher salt<br />

2 teaspoons sugar<br />

2 teaspoons chili powder<br />

Zest of 1 lime, plus lime wedges for serving<br />

2 cups fresh watermelon juice<br />

4 ounces of tequila<br />

2 ounces fresh citrus juice (any combination of orange, lemon, and lime)<br />

1/2 ounce agave nectar<br />

1 bunch fresh basil leaves, plus more for garnish<br />

1 bunch fresh mint leaves, plus more for garnish<br />

1 small jalapeño, sliced and seeded, plus more for garnish<br />

Ice<br />

INSTRUCTIONS:<br />

Mix together the salt, sugar, chili powder, and lime zest on a small, shallow<br />

plate. Use lime wedges to wet the rims of two glasses, then gently press the<br />

rims into the salt mixture to coat.<br />

Fill a cocktail shaker with watermelon juice, tequila, citrus juice, agave, 3<br />

leaves each of the basil and mint, and jalapeño. Add ice and shake well, until<br />

the outside of the shaker is cold, about 30 seconds.<br />

Strain cocktail through a strainer and fill the prepared glasses with the<br />

watermelon cocktail. Garnish each with basil, int and jalapeño.<br />

Recipe excerpt from Son of a Southern Chef: Cook With Soul published by<br />

Penguin Random House (https://bit.ly/37UASDD). Listen to I’m Gay on Spotify<br />

(spoti.fi/37Mhoke)<br />

82 aphrochic issue four 83

Travel<br />

Tobago<br />

in Color<br />

The Island’s Real<br />

Treasures Are Its<br />

People and Culture<br />

Photos by David A. Land<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

84 aphrochic

Travel

Travel<br />

Tobago is beautiful. With lush rainforests, towering mountains and<br />

endless beaches, it is beautiful in a way rivaled only by those few places<br />

equally fortunate to be located somewhere in the Caribbean Sea. It’s easy<br />

to believe that when Christopher Columbus first set foot on the island in the<br />

last years of the 15th century, that the beauty of the place was the first thing<br />

he noticed. Despite all the harm he caused, and all that transpired after as<br />

colonial powers struggled to control it, the island, which was conquered and<br />

reconquered more than thirty times, remains beautiful. Linked to Trinidad<br />

since the 1800s, the twin nations entered freedom together, liberated from<br />

British control in 1962, becoming a joint republic in 1976.<br />

At only 116 square miles, Tobago offers a startling variety of natural<br />

terrains. In addition to rainforests, mountains and beaches, the island is<br />

home to foothills, plains, mangrove swamps, waterfalls, and coral reefs.<br />

Its historical imprint is wide as well as it shares with Trinidad the pride of<br />

adding CLR James, Eric Williams, and Henry Sylvester Williams, among<br />

others to the international college of thinkers, activists and politicians who<br />

have shaped our collective notion of Blackness through their work.<br />

The island’s true treasures, however, are its people and culture. What<br />

Tobago calls its own are its traditional dances — the salaka, the reel, and the<br />

jig — and tambrin, the uniquely Tobagonian musical style that often accompanies<br />

them. Festivals and celebrations commemorate the history of the<br />

island and the culture of the people, highlighting what is uniquely their own<br />

while honoring the connection to Africa that unites us all.<br />

After centuries of colonization, the long fight for freedom and the work<br />

of creating a new culture, through it all the beauty of the Tobago, its people<br />

and heritage are plain to see. AC<br />

88 aphrochic issue four 89

Travel

Travel<br />

92 aphrochic issue four 93

94 aphrochic issue four 95

issue four 97

Wellness<br />

Plant Life<br />

Evann E. Webb, Social<br />

Media Specialist for<br />

Bloomscape, Talks to Us<br />

About How Plants Can Aid<br />

in Your Wellness Routine<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos by Cyrus Tetteh

Wellness<br />

Whether you’re looking to be an expert home gardener growing your own salads and herbs,<br />

or just a capable plant parent able to keep things green for as long as possible, the world of<br />

plants has become one of the biggest home trends of 2020. Sustainable, affordable, and with<br />

big benefits for health and wellness, plant life is attracting a growing number of homeowners<br />

— especially millennials — who are looking to breathe new life into their spaces. And with so<br />

many of us only able to watch the seasons change through our windows, who wouldn’t love to<br />

bring a bit of the outdoors in? Growing along with the trend, a whole new crop of brands have<br />

sprung up, ready to help you not only find the perfect plants for your home, but care for them as<br />

well. We sat down with Evann E. Webb, the woman who runs social media for the Detroit-based<br />

brand Bloomscape to discuss all things plants and wellness.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>: The houseplant industry is thriving right now, especially<br />

among millennials. Why do you think that is?<br />

Evann E. Webb: Millennials aren’t settling down or making super<br />

heavy commitments at the same ages our parents were. And it’s not<br />

because we don’t want to. It’s because a lot of us can’t right now. The<br />

economy isn’t set up in a way that makes starting a family or buying a<br />

forever home ideal for us at the moment. So many of us have hundreds<br />

of thousands of dollars in student loans, are still looking for jobs that<br />

pay us reasonable salaries, and to put it more plainly — trying to<br />

figure things out for ourselves. Buying plants still allows us to make<br />

rental spaces feel like home, and gives us the opportunity to care of<br />

something other than ourselves — without having to break the bank!<br />

AC: What plants do you have at home and what does your plant<br />

care routine look like?<br />

EW: Right now, I have a ZZ Plant, a Bird of Paradise, and two<br />

Philodendron Heartleafs. Since I’ve been working from home for<br />

the past few months, I’ve been making it a habit to mist my Bird of<br />

Paradise and Philodendron Heartleafs every day, and on the weekends<br />

I check the plants’ soil to see if they need to be watered. Being cooped<br />

up in the house has definitely made me reevaluate my space, and I’ll be<br />

ordering some more plants and plant stands soon! I need all the green<br />

I can get right now.<br />

AC: The last few months have definitely been challenging with<br />

an ongoing pandemic. As we physically distance and spend more time<br />

inside, how can caring for plants be part of our self-care routine?<br />

EW: Caring for plants is a meditative practice. It allows you to<br />

take a step away from the computer, phone and television and focus<br />

on the present. Turning on some relaxing music and taking an hour or<br />

two each week to water, trim, mist or re-pot really is soothing.<br />

AC: Part of the difficulty in caring for plants is the level of care<br />

that some plants require. How does Bloomscape help those who might<br />

be green thumb-challenged pick the right options for their lifestyle?<br />

EW: Some of the easiest plants to care for that we offer are<br />

the Bird of Paradise, our Tough Stuff Collection, the Monstera, the<br />

Silver Pothos and the Hedgehog Aloe. With each order, we give every<br />

customer detailed care instructions. Information can be found<br />

right on the care card, and we have a series of blog posts that feature<br />

different care tips and educational info from our resident Plant Mom<br />

that are always available to read.<br />

AC: Just as different plants require their own levels of care, they<br />

can have different roles in the home. What are the best plants that we<br />

can have at home with us right now that will help us have a cleaner,<br />

healthier environment? Are there some you like best for decorating?<br />

EW: I love how my four little plant babies have transformed my<br />

space. It’s so interesting how no matter what your style of decor is,<br />

there’s a plant that can help tie everything together. Some of the best<br />

plants to have at home are the Sansevieria (it helps to purify the air),<br />

the Money Tree, our Fur Friendly Collection (for all the pet parents out<br />

there), the Red Pear Plant, and the Bamboo Palm.<br />

AC: So many people we know (including us) who have tried<br />

keeping plants in their apartment have horror stories about how hard<br />

it is, and guilt over what happened to their little green friends. What<br />

are the steps to being good plant parents?<br />

EW: I’m still learning how to be a good plant parent myself. Lol!<br />

To me, the first step is practicing patience. Plants are living things,<br />

and some of them are quite sensitive. So understanding that, and<br />

realizing that you’re not going to see immediate growth overnight, is<br />

really important. Also, give yourself some grace. It’s a natural thing<br />

to feel sad when your plant journey isn’t going well (I have admittedly<br />

killed my fair share of plants), but I’m learning that a lot of this is trial<br />

and error. I know now that plants that require a ton of TLC aren’t my<br />

thing, so I try to stick to more low-maintenance ones. Learning what<br />

works best for you and your everyday schedule or routine will definitely<br />

be helpful in the long run.<br />

AC: One last question. With so many companies offering plants<br />

right now, what sets Bloomscape apart from other plant brands?<br />

EW: The company’s desire to see its customers succeed as plant<br />

parents. When you order a plant from Bloomscape, you get detailed<br />

instructions on how to care for it, from what kind of light it needs all<br />

the way down to humidity and how often you should fertilize it. Plus,<br />

we make it easy for customers to contact us if they need any extra help<br />

or advice.<br />

100 aphrochic issue four 101

Reference<br />

The Emergence<br />

of Diaspora<br />

The world of Pan-Africanism in the 1960s was very different from the one into which<br />

the Trinidadian lawyer Henry Sylvester Williams first introduced the term in 1900. <strong>No</strong>t<br />

only had 60 years passed, but with them two World Wars that had depleted the empires<br />

of Europe, loosening the stranglehold they once held on much of the rest of the world.<br />

But the impact of time wasn’t felt by Europe alone. Pan-Africanism had made its share<br />

of strides in that time as well.<br />

From Pan-Africanism To Diaspora<br />

Five Pan-African Congresses had passed<br />

since Williams’ original conference, with<br />

more to come. The New Negro Movement, The<br />

Harlem Renaissance, and Negritude all came<br />

and went in their time along with countless<br />

other movements, organizations, journals and<br />

groups. In the wake of their relentless pursuit<br />

of liberation, cracks had begun to form in the<br />

facade of colonial power.<br />

Progress was also coming to internally<br />

colonized nations like the United States. The<br />

American Civil Rights Movement was reaching<br />

its peak in a decade that would see the passing<br />

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights<br />

Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Yet<br />

in the victories of Pan-Africanism lay the seeds<br />

of its dissolution. Soon it too would fade away.<br />

With many of its goals achieved, but so much<br />

left to be done, the passing of Pan-Africanism<br />

would prove a necessary step, paving the way<br />

for something new — diaspora.<br />

As a concept, the African Diaspora was<br />

officially born in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. in<br />

1965. Two papers presented at the First International<br />

Congress on African History -<br />

convened under Tanzania’s first president<br />

Julius Nyerere — introduced the term to the<br />

world. The first, The African Abroad or the<br />

African Diaspora, by British historian George<br />

Shepperson is often credited as the first use of<br />

the term “diaspora” with regard to the historical<br />

dispersal of Africans. Shepperson himself<br />

preferred to share the distinction of this<br />

milestone with the African American scholar<br />

and author Joseph Harris, whose address,<br />

Introduction to the African Diaspora, appeared<br />

at the same conference. Though not himself a<br />

member of the diaspora he helped to define,<br />

Shepperson was an assiduous researcher and<br />

theorist of Pan-Africanism and the African<br />

Diaspora and remained so until his passing<br />

early in 2020.<br />

In a later essay, Shepperson would trace<br />

the history of the diaspora concept to such<br />

figures as Edward Wilmot Blyden, W.E.B.<br />

Du Bois, and Lorenzo Dow Turner, marveling,<br />

as so many have since, that so much time<br />

should have passed before “diaspora” was<br />

added to the arsenal of terms with which<br />

people of African descent fought for their historical<br />

position. In particular, he singled out<br />

Blyden, whose work employed so many biblical<br />

references, and revolved around a concept so<br />

Dr. Edward Wilmot Blyden.<br />

Sir Harry Johnston,<br />

Liberia, (London: Hutchinson<br />

& Co., 1906). General<br />

Research and Reference<br />

Division, Schomburg<br />

Center for Research in<br />

Black Culture, The New<br />

York Public Library.<br />

The Second Pan-African Congress. Special Collections & University Archives,<br />

W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.<br />

W.E.B. Du Bois.<br />

Photographs and Prints<br />

Division, Schomburg Centers<br />

for Research in Black Culture,<br />

The New York Public Library.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

102 aphrochic issue four 103

Reference<br />

near to diaspora, yet which never seemed to<br />

openly connect the phrase.<br />

The Politics of Pan-Africanism<br />

Despite the lengthy progress of forbears<br />

that Shepperson cited as constituting the long<br />

march to diaspora, the conceptual point of<br />

origin can be found earlier in his own work,<br />

specifically in his wrestling with the meaning<br />

and uses of the term, “Pan-Africanism.”<br />

In response to what he termed, “a most<br />

inadequate section on African Nationalism,”<br />

in the second book of the Tropical Africa series,<br />

by George H. T. Kimble, Shepperson wrote the<br />

concise but dense article, Pan-Africanism and<br />

“Pan-Africanism”: Some Historical <strong>No</strong>tes. In it,<br />

Shepperson made it clear that he took issue<br />

with Kimble’s simplistic description of Marcus<br />

Garvey’s political and economic philosophies<br />

as “the alloy of pan-Africanism … smelted into<br />

the ore of Ethiopianism.” In response, Shepperson<br />

clarified his position on the proper<br />

meaning and use of the term Pan-Africanism,<br />

dividing it into two separate terms, one with a<br />

capital “P,” and the other a lowercase “p”.<br />

The distinction between the two confines<br />

the overtly political “Pan-African” movement<br />

to the wide sphere of influence of W.E.B.<br />

Du Bois, whom he posits as the official center<br />

of the movement. Meanwhile, the lowercase<br />

“pan-Africanism,” consists of all of the more<br />

culturally-focused and less centralized<br />

movements that were also happening at the<br />

time — such as the Black Arts Movement —<br />

along with any political movements with no<br />

“organic relationship” to Du Bois’ Pan-Africanism.<br />

Shepperson placed Marcus Garvey,<br />

whose enmity with Du Bois was well established,<br />

somewhere between the two.<br />

While we are free to debate the efficiency<br />

of his approach to the problem (which also<br />

included the addition of a third term: “All-African”),<br />

Shepperson’s struggle to contain<br />

so many movements under a single term<br />

demonstrates the emerging limitations of the<br />

Pan-African concept. As Brent Hayes Edwards<br />

observed:<br />

On the one hand, Shepperson<br />

rereads the term precisely to make<br />

room for ideological difference and disjuncture<br />

in considering black cultural<br />

politics in an international sphere …<br />

In Shepperson’s view, it is crucial to be<br />

able to account for the transformative<br />

‘sea changes’ that Pan-African thought<br />

undergoes in a transnational circuit.<br />

Among the "sea changes" that Edwards<br />

mentions were the issues associated with<br />

communicating competing ideologies<br />

between languages. The many differences that<br />

separated the various forms of Pan-Africanism<br />

together with the scope of activity taking<br />

place on several continents, made the process<br />

of Internationalism (a term employed here to<br />

include both forms of Pan-Africanism) one of<br />

continual translation. This difficulty added to<br />

the already numerous gaps between groups —<br />

gaps that were widening in importance at the<br />

moment of Shepperson’s reconsideration of<br />

the term. His solution, Edwards reflects, was<br />

to work, “toward a revised or expanded notion<br />

of black international work that would be able<br />

to account for such unavoidable dynamics of<br />

difference, rather than either assuming a universally<br />

applicable definition of ‘Pan-African’<br />

or presupposing an exceptionalist version of<br />

New World ‘Pan-African’ activity.”<br />

Reconciling the needs of the quickly<br />

changing landscape with any of the constructions<br />

of Pan-Africanism available at the time<br />

quickly proved to be more than the concept<br />

could bear. Something new was needed. The<br />

process of becoming a conceptual diaspora<br />

therefore was not a simple one of connecting<br />

the story of African dispersal to that of<br />

Jewish dispersal as told in the Bible and other<br />

histories. Instead, the African Diaspora<br />

concept emerged as the result of a process of<br />

outgrowing the unilateral vision of a single,<br />

mono-centric Pan-African movement. Yet, the<br />

transition away from Pan-Africanism didn’t<br />

come about because the strategies and efforts<br />

that comprised its movements hadn’t worked,<br />

but because they had.<br />

The Birth of Many Nations<br />

The catalyst which would begin to<br />

render obsolete what the celebrated anthropologist<br />

St. Clair Drake called “traditional<br />

Pan-Africanism”, was the accomplishment<br />

of the political liberation that the movement<br />

had labored for so long to realize. As Drake<br />

framed it, “[T]he period of uncomplicated,<br />

united struggle to secure independence from<br />

the white oppressor ended for each colony as it<br />

became a nation.”<br />

With the gradual absence of a ubiquitous<br />

force of oppression came the crumbling of<br />

the amalgamated front that had been erected<br />

to resist it. Africa was no longer the centerpiece<br />

of an internationally-aligned struggle<br />

for independence. Divergent national identities<br />

emerged as political priorities diversified.<br />

New African and Caribbean nations turned to<br />

questions of self-governance, while those on<br />

the American continent devoted themselves to<br />

the fight for civil rights and equality at home.<br />

Meanwhile, in Africa, a series of armed<br />

coups led to what Drake termed “a parade to<br />

the seats of power of military men who had no<br />

allegiance to the kind of sentimental Pan-Africanism<br />

[that their predecessors espoused],<br />

and who were without any previous experience<br />

in dealing with West Indians and Afro-Americans.”<br />

Yet despite this political parting of ways,<br />

the sense of connection culturally, historically,<br />

if not politically, remained and demanded new<br />

modes of articulation.<br />

New words, that would embrace the<br />

legacy of Internationalism, support cultural<br />

pan-Africanism, and yet loosen the bonds of<br />

a Pan-African ideology based on a common<br />

political destiny that stratified even as it was<br />

being achieved. Shepperson’s nomination of<br />

diaspora filled that gap.<br />

It’s questionable whether Henry<br />

Sylvester Williams envisioned Pan-Africanism<br />

as a singular movement, or if he imagined the<br />

number of activities, groups, and leaders that<br />

would eventually be gathered under the term<br />

— or all that they would accomplish. That it<br />

was ultimately unable to contain the multitude<br />

of ideas that grew under its umbrella was<br />

perhaps the greatest mark of Pan-Africanism’s<br />

success.<br />

The vision of what Black Liberation<br />

was, what it would mean and how it could be<br />

achieved was never truly singular, even within<br />

a single organization. But there was a certain<br />

unity of direction that became difficult to<br />

maintain as African colonies became African<br />

nations, and the restricted yet somewhat<br />

generalized national identity of the “African<br />

Abroad” became specifically “Trinidadian,”<br />

“Jamaican,” “African American” and so on.<br />

The solidification of national identities<br />

and the necessary separation of political goals<br />

that attended it created a level of self-interest<br />

that was antithetical to the “Pan” element of<br />

“Pan-Africanism.”<br />

Diaspora, therefore makes a timely<br />

entrance into a conversation that was just<br />

beginning to turn from the politics of unity to<br />

a deeper exploration of the meanings of difference<br />

in the global Black community.<br />

What remains of Pan-Africanism today<br />

is largely culturally focused. Though it would<br />

be inaccurate to ever categorize Black cultural<br />

activity as apolitical, to the extent that any<br />

unified Pan-African movement could be said<br />

to exist today, it lacks much of the ability to<br />

influence policy that Du Bois and other leaders<br />

had at the height of their activity. Harris and<br />

Shepperson introduced diaspora as, undoubtedly,<br />

the more accurate description of<br />

the amalgam of African and Africa-descended<br />

cultures that cross the world today.<br />

However, there is still much that the<br />

focus and intensity of Pan-Africanism could<br />

teach to its far less politically-inclined<br />

successor.<br />

And as the strength and support behind<br />

the Movement for Black Lives and other<br />

groups continues to grow, inspiring protests<br />

across the world in response to the continued<br />

murder of Black people by police in America,<br />

the examples of Pan-Africanism’s chief<br />

leaders, strategists, and theorists may be<br />

becoming more relevant by the day. AC<br />

Marcus Garvey in Regalia, 1924. James VanDerZee. Copyright Donna Mussenden<br />

VanDerZee. All rights reserved. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Centers for<br />

Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.<br />

The Ethiopian World Federation. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Centers for<br />

Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.<br />

104 aphrochic issue four 105

Sounds<br />

Ranky Tanky<br />

The Award-Winning Quintet’s Latest Album Good Time Offers<br />

the World s Taste of the Gullah Music of the Carolina Coast<br />

There was a time when African<br />

American culture was thought to be devoid of<br />

“Africanisms,” those unique cultural components<br />

that are direct survivals of older, African<br />

practices. The idea was that the form of<br />

slavery practiced in the United States was so<br />

complete in its extermination of pre-existing<br />

culture among those it enslaved that no such<br />

links remained. It was never true, of course.<br />

Finding Africa in American culture is easy —<br />

just listen to the music. Better yet, listen to<br />

where it came from.<br />