You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FEBRUARY 4, 2021

WEEKLYNEWS.NET - 978-532-5880 13

Cancer treatment crosses a frontier

Harold Brubaker

The Philadelphia

Inquirer

PHILADELPHIA – As she

fights cancer, Lisa Oney is not

shackled to a hospital bed for days

at a time, stuck there while she is

infused with chemotherapy drugs.

She’s undergoing chemo at

home — even on the move. At

times, the life-saving medicine is

flowing into her as she drives to

make curbside pickups at Target.

Thanks to a new program at

Penn Medicine, Oney, 33, carries

her chemotherapy medicine in a

backpack with a small pump that

feeds the drug into her body. “I’m

able to walk around, and take care

of my kids,” she said. “I can go

places.”

Typically, her particular regimen

of chemotherapy would require

several five-day stays in the hospital

spread over 18 weeks. The

trouble was, Oney needed to be

home in Souderton to care for her

3-month-old son and 3-year-old

daughter.

“I couldn’t do that,” she said,

referring to the hospital visits.

“My husband wouldn’t be able to

work.”

Because of COVID-19, Oney

and her husband, Kevin O’Driscoll,

also can’t accept help from friends

and coworkers. The risk of her

catching the coronavirus or something

else is too great.

Chemotherapy at home is a

rising trend, driven by patient convenience

and the widespread fear

of hospitals during the pandemic.

But as much as patients love it,

antiquated health-care billing systems,

especially in Medicare, remain

a formidable obstacle to the

practice.

Penn’s shift of some chemotherapy

treatments to home started

on a small scale before the pandemic,

but then took off, according

to Justin Bekelman, the radiation

oncologist who directs the Penn

Center for Cancer Care Innovation

Under the at-home process, Penn

nurses drive to patients’ residences

to set up the complex lines and

do the injections involved in the

cancer treatment, which in Oney’s

case continues for days. After that,

the backpack-wearing patients are

free to go about their lives.

Bekelman said that Penn had

good reasons to launch the effort.

“It’s obviously patient-centric and

will enhance patients’ experience

of cancer treatment,” he said, “but

also our infusion suites were all full

up.”

Most experts see the move as

positive for employers and taxpayers,

who pay much of the cost

of health care. Insurers pay less for

patients who choose an at-home

option as opposed to infusion at

their main facility or even a specialist’s

office.

Aetna, a major health insurer

in the Philadelphia region, said

last year that a single infusion of

a specialty drug in a hospital, even

on an outpatient basis, costs more

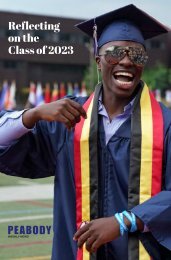

PHOTO | PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER

Lisa Oney juggles her chemotherapy treatment bag on her right shoulder and three-month-old

Jack O’Driscoll in her left arm while daughter Fiona O’Driscoll, 3, has a snack in the kitchen.

than $20,000. The savings from

moving it to an independent outpatient

center can exceed 50%, it

said. Home treatments save about

the same, experts said.

But chemo in the home means

much less money for hospitals,

Bekelman noted, making it harder

to expand the treatments.

“We need a payment model that

keeps health-care providers whole

irrespective of where we deliver

the treatment,” he said. “That’s a

crucial incentive for health systems

to invest in providing more care at

home and other less expensive locations

— a shift that should ultimately

save insurers money.”

A more logical payment system

would promote changes such as inhome

chemotherapy. And there has

been some movement in that direction,

said Larry Levitt, a health

policy scholar at the Kaiser Family

Foundation. One approach would

be to uncouple insurance payments

from specific procedures, he said.

“The concept is to pay providers

a flat amount for certain patients or

conditions,” Levitt said, “and let

the providers figure out the best

way to deliver care, keeping any

savings they realize.”

He added: “The key is to build

in safeguards to prevent providers

from skimping on care.”

Not a new concept

Since at least the mid-1990s,

home health care companies have

talked about providing in-home

chemotherapy, but little has come

of it.

John Sprandio, an oncologist

with offices in Delaware and

Chester Counties, welcomes athome

chemotherapy, but cautions

that it is actually more costly to

provide than many realize.

“In terms of efficiency,”

Sprandio said, “it’s obviously more

cost-effective to administer these

drugs for the majority of patients in

a group setting where you have a

team of a dozen nurses and 28 or

30 treatment areas that’s equipped

to handle anything.”

Meanwhile, major trade associations

such as the American Society

of Clinical Oncology and the

Community Oncology Alliance

have formally opposed the practice.

In statements last year, they

cited a fear that patients might have

a bad drug reaction with no doctors

nearby.

Richard Snyder, chief medical

officer for the parent company of

Independent Blue Cross, said he

was convinced that the trend was

safe.

“Physicians and hospitals tend

to be creatures of habit,” Snyder

said. “We keep doing what seems

to work for us, and so we’re not inclined

to change our habit of giving

the medication in a hospital or a

higher-cost setting.”

Snyder described Penn as being

at the forefront of moving chemotherapy

to the home, where the patient

is probably as safe as possible

from exposure to COVID-19 and

other infections.

Penn’s Cancer Care at Home

program ramped up from 39 patients

in March to more than 300

within a month as patients were

eager to avoid hospitals. In all of

last year, nearly 1,500 Penn patients

received in-home chemo.

Currently, patients with breast

cancer, prostate cancer and lymphoma

are candidates for the program,

Bekelman said. Penn hopes

to add patients with lung cancer,

head and neck cancers, and others,

but that depends on higher reimbursements

and other changes to

insurance plans.

Bekelman said the goal wasn’t

to transfer all cancer care, but to

establish that it can be done safely

off premises.

He noted that there were some

limits because the risk of side effects

was too severe with some

chemo drugs.

Other Philadelphia-area providers

of cancer care are not as

active. Jefferson Health’s Sidney

Kimmel Cancer Center has helped

only 50 or so in-home patients in

recent years. Fox Chase Cancer

Center said it has no plans to join

the trend. Nor does MD Anderson

Cancer Center at Cooper hospital

in Camden.

Nationally, CVS Health has

joined Penn in trying to move

more chemotherapy treatments to

homes. This month, CVS, which

owns Aetna, announced that its

infusion unit, Coram, would work

with Cancer Treatment Centers

of America to do that, starting in

Atlanta.

The insurance problem

Limiting wider adoption of inhome

chemotherapy is a legacy

payment system that provides

much larger reimbursement

when the treatments are done at a

hospital.

Comparisons for such costs at

different sites are hard to find. But

a 2019 report showed that the average

claim for an injection of infliximab,

used to treat autoimmune

diseases, was about $3,100 in a

physician’s office, compared with

$5,800 in a hospital’s outpatient

department. Bekelman said that

the same pattern holds for chemotherapy

drugs and that reimbursement

at home is similar to in a physician’s

office.

Jefferson’s Sidney Kimmel

Cancer Center has received widely

varying reimbursement rates for

home infusion. Some plans reimburse

“on par with on-site infusion,

Offer available to new subscribers only

while others reimburse at very

low levels or not at all,” Karen E.

Knudsen, a top oncology expert at

Jefferson, said in an email.

Timothy Kubal, an oncologist

who directs the infusion center

at the Moffit Cancer Center in

Tampa, Fla., predicted that much

more cancer care could be provided

in the home within a decade,

“but in between now and then,

there’s going to be a lot of conversation

about what’s the right rate.”

The patient’s perspective

The bulk of the cancer patients

Penn has been treating at home —

instead of at an infusion center —

are receiving injections for breast

and prostate cancer. Penn Home

Infusion nurses work around the

patients’ schedules to they don’t

have to lose time at jobs, Bekelman

said.

Avoiding a hospital stay, as

Oney, the patient from Souderton,

is doing, is an even bigger deal

during the pandemic.

“We have generally seen

that being in the hospital can be

tough, no family, food is different.

Depression can set in, so overall

I think this is a good trend if patients

can manage at home,” said

Kelly Harris, CEO of the nonprofit

Cancer Support Community

Greater Philadelphia.

Oney was diagnosed with lymphoma

in November, just two

weeks after her son was born.

Before she began receiving steady

treatment at home, she was given

her first round of chemo in the hospital

to ensure that she didn’t have

an adverse reaction.

There was none. But on one later

evening, Oney, a neonatal nurse

at Grand View Hospital in upper

Bucks County, got a headache as

soon as the infusion started — possibly

because she had forgotten to

take the medication out of the refrigerator

ahead of time.

Oney got a quick response from

Penn’s on-call oncologist, who told

her to take ibuprofen. “It’s all very

connected,” she said.

Although being home doesn’t

head off the miserable side effects

of chemotherapy, she considers it

a blessing to avoid those overnight

hospital says.

Local news on your doorstep

Home delivery starts at only $4.50 per week.

50% off your first month of home delivery

when you use coupon code dailyitem

at checkout at www.itemlive.com