Aphrochic Magazine: Issue No. 7

For our Summer 2021 issue, we have an issue full of color, life and all of the things that make our Diaspora beautiful. For our cover story, we are thrilled to sit down with one of our favorite folks in fashion, the amazing Charles Harbison. After a 5-year hiatus and a cross-country jump from New York to Los Angeles, Charles is back with the much-anticipated return of his eponymous fashion line, HARBISON. We also sit down with the iconic Dyana Williams. A legend of the Philadelphia radio scene that we grew up on, she’s better known outside the city as the mother of Black Music Month. We sat down with Dyana to talk about Black music, the newly opened National Museum of African American Music and the artists on her playlist that she feels are doing the most for the culture. In our Hot Topic, AphroChic contributor Ruby Brown takes an incisive look at Pride, all that the LGBTQIA+ community has accomplished and all that’s left to do. And in response to the growing debate over Critical Race Theory, which in the last months has taken over news feeds and legislative floors alike, we take a break from our ongoing discussion of the African Diaspora to offer a brief exploration of CRT, it’s origins, it’s concepts and why it seems to have everyone so upset. Throw in some amazing art from THE CONSTANT NOW gallery in Antwerp, inspirational words from author Alexandra Elle, and the latest updates from the outdoor spaces at the AphroFarmhouse and we think this issue will have you ready for the summer season.

For our Summer 2021 issue, we have an issue full of color, life and all of the things that make our Diaspora beautiful. For our cover story, we are thrilled to sit down with one of our favorite folks in fashion, the amazing Charles Harbison. After a 5-year hiatus and a cross-country jump from New York to Los Angeles, Charles is back with the much-anticipated return of his eponymous fashion line, HARBISON. We also sit down with the iconic Dyana Williams. A legend of the Philadelphia radio scene that we grew up on, she’s better known outside the city as the mother of Black Music Month. We sat down with Dyana to talk about Black music, the newly opened National Museum of African American Music and the artists on her playlist that she feels are doing the most for the culture.

In our Hot Topic, AphroChic contributor Ruby Brown takes an incisive look at Pride, all that the LGBTQIA+ community has accomplished and all that’s left to do. And in response to the growing debate over Critical Race Theory, which in the last months has taken over news feeds and legislative floors alike, we take a break from our ongoing discussion of the African Diaspora to offer a brief exploration of CRT, it’s origins, it’s concepts and why it seems to have everyone so upset.

Throw in some amazing art from THE CONSTANT NOW gallery in Antwerp, inspirational words from author Alexandra Elle, and the latest updates from the outdoor spaces at the AphroFarmhouse and we think this issue will have you ready for the summer season.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

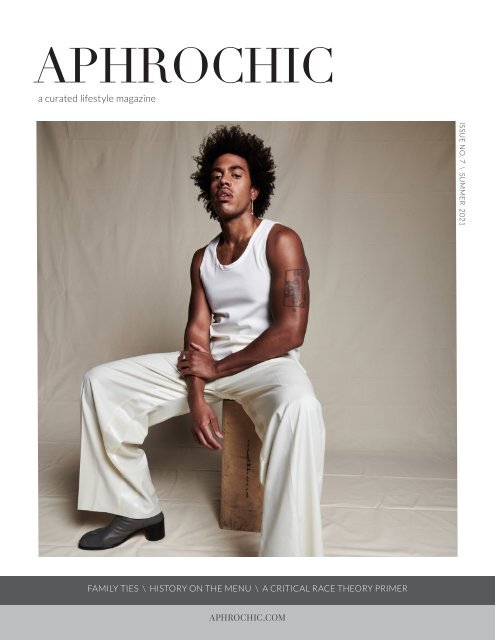

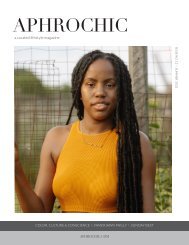

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 7 \ SUMMER 2021<br />

FAMILY TIES \ HISTORY ON THE MENU \ A CRITICAL RACE THEORY PRIMER<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

SLEEP ORGANIC<br />

Avocado organic certified mattresses are handmade in sunny Los Angeles using the finest natural<br />

latex, wool and cotton from our own farms. With trusted organic, non-toxic, ethical and ecological<br />

certifications, our products are as good for the planet as they are for you. Shop online for fast<br />

contact-free delivery. Start your organic mattress trial at AvocadoGreenMattress.com

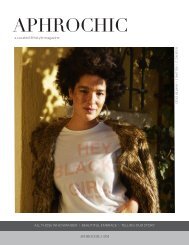

Summer is here and we are ready! After more than a year inside, we are vaccinated<br />

(hopefully you are, too) and ready to get some sun. We’re especially happy to<br />

celebrate the return of AphroChic founder and creative director Jeanine Hays to the<br />

editor’s desk. The road to recovery post-COVID has been long, and while we’re still<br />

on it, she’s getting stronger day by day.<br />

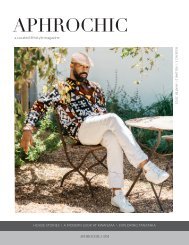

To celebrate, we have an issue full of color, life, and all of the things that make our Diaspora beautiful. In this<br />

issue, we are thrilled to sit down with one of our favorite folks in fashion, the amazing Charles Harbison. After<br />

a five-year hiatus and a cross-country jump from New York to Los Angeles, Charles is back with the much-anticipated<br />

return of his eponymous fashion line, HARBISON. We also sit down with the iconic Dyana Williams. A<br />

legend of the Philadelphia radio scene that we grew up on, she’s better known outside the city as the mother of<br />

Black Music Month. We sat down with Dyana to talk about Black music, the newly opened National Museum of<br />

African American Music, and the artists on her playlist that she feels are doing the most for the culture.<br />

In our Hot Topic, AphroChic contributor Ruby Brown takes an incisive look at Pride, all that the LGBTQIA+<br />

community has accomplished, and all that’s left to do. And in response to the growing debate over Critical Race<br />

Theory, which in the last few months has taken over news feeds and legislative floors alike, we take a break from<br />

our ongoing discussion of the African Diaspora to offer a brief exploration of CRT, its origins, its concepts, and<br />

why it seems to have everyone so upset.<br />

Throw in some amazing art from THE CONSTANT NOW gallery in Antwerp, inspirational words from author<br />

Alexandra Elle, and the latest updates from the outdoor spaces at the AphroFarmhouse and we think this issue<br />

will have you ready for the summer season. So find a sunny spot, put on some Black music that you appreciate,<br />

and welcome to lucky issue #7!<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, AphroChic<br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

SUMMER 2021<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Watch List 12<br />

The Black Family Home 14<br />

Mood 20<br />

FEATURES<br />

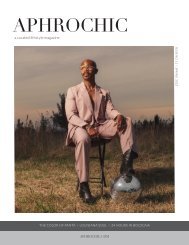

Fashion // Transformation, Rebirth, and Re-Emergence 26<br />

Interior Design // Family Ties 40<br />

Culture // Lit! 52<br />

Food // History on the Menu 56<br />

Travel // The Goodtime Hotel 64<br />

Entertaining // Brunch with Purpose 80<br />

Reference // Talking Points 86<br />

Sounds // Celebrating Our Sound 92<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 102<br />

Hot Topic 106<br />

Who Are You? 112

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover photo: Charles Harbison<br />

Photographer: Lee Morgan<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

AphroChic<br />

AphroChic.com<br />

magazine@aphrochic.com<br />

Sales Contact:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

ruby@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors (left to right below):<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

issue seven 9

READ THIS<br />

The poet Gwendolyn Brooks — the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize — wrote in a poem<br />

dedicated to the actor Paul Robeson: “We are each other's harvest, we are each other's business, we are<br />

each other's magnitude and bond.” Her quote was a call to every person, to remind them that we are all<br />

part of a larger community, responsible for each other. Our book selections in this issue all have that<br />

"call to action" as their common theme — they each shine a spotlight on communities within the larger<br />

Diaspora. The first takes its name directly from Brooks' poem, showcasing the Black farming communities<br />

that were once thriving and are now being regrown by a group of young farmers. Queer Love in Color gives<br />

an inclusive look at what it means to love and live at the intersections of queer and POC identities. And<br />

AfroSurf highlights the unique surf culture of 18 coastal countries in Africa while also supporting the<br />

critical need for suf tourism in local economies.<br />

Queer Love in color<br />

by Jamal Jordan<br />

Publisher: Ten Speed Press. $23.99<br />

We Are Each Other's Harvest<br />

by Natalie Baszile<br />

Publisher: Amistad. $19.99<br />

AfroSurf<br />

by Mami Wata<br />

Publisher: Ten Speed<br />

Press. $32<br />

10 aphrochic<br />

Well-traveled home goods, from the rug up.<br />

REVIVALRUGS.COM

WATCH LIST<br />

Public art is perfect for summer days, and an outdoor digital exhibit in Atlanta is celebrating artists<br />

and the South. The South Got Something to Say, curated by Karen Comer Lowe, showcases artwork by 10<br />

Atlanta-based artists on four A&E Atlanta digital signs throughout downtown Atlanta. Running through<br />

July 31, the title of the exhibit comes from something Atlanta-based rapper Andre 3000 said at the Source<br />

Awards in 1995. Lowe says, “That phrase [about the South] issued a proclamation about the rising impact<br />

of Atlanta as a city. Since that time, the city has risen as an influential force in music, film, and politics.<br />

This digital exhibition is a recognition of the visual culture of Atlanta and the people who contribute<br />

to that culture. The works, while variant in medium, address a reckoning with the intersectional<br />

inequities of our being.” The featured artists include Sheila Pree Bright, Jurell Cayetano, Alfred Conteh,<br />

Ariel Dannielle, Shanequa Gay, Kojo Griffin, Gerald Lovell, Yanique <strong>No</strong>rman, Fahamu Pecou, and Jamele<br />

Wright. Interestingly, the works are mostly filled with color and joy, offering a post-pandemic form of<br />

celebration in the great outdoors.<br />

Flat Splat, Just Like That<br />

by Jamele Wright<br />

Mixed Media on a Found Canvas<br />

12 aphrochic<br />

serenaandlily.com

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Navigating Outdoor Space<br />

As a child I loved being outdoors. I was born in the summer and it always felt like the most natural time<br />

to me. Feet bare, I would spend hours in the sunshine, playing, picking flowers, dreaming of the life<br />

I would one day have. Back then my dream house was surrounded by apple trees. It had a giant front<br />

porch and lots of space to stretch out in out back. Looking around today, I see that my dream has largely<br />

materialized (give or take some apple trees). But the road here was long and hard. I spent a lot of last year,<br />

and this year, extremely ill. I watched a summer of police violence turn into a winter of insurrection and<br />

now a not-at-all-subtle attempt to silence our voices and our votes.<br />

Looking at all my newfound yard<br />

space for the first time in the summer sun,<br />

I found myself wondering: <strong>No</strong>w that I had<br />

it, did I still want it? I started thinking a<br />

lot about the child that I was and the home<br />

that she dreamt of — how it feels; if it’s safe;<br />

and how my husband and I, as Black people<br />

in America, can navigate our very own<br />

outdoors.<br />

Moving into a 1930s farmhouse, one<br />

thing that grabbed us immediately was the<br />

front porch. If you’re from the Philadelphia<br />

area, you know that front porch culture is<br />

a very big thing. My nana and porgie used<br />

to sit out on their front porch all summer<br />

long. They would say hi to the passersby,<br />

greet us on the porch when we visited,<br />

and they also knew all of the comings and<br />

goings of the block, clocking everything<br />

that went on from their front porch vista.<br />

The porch at the AphroFarmhouse<br />

reminded me a lot of their home in the<br />

suburbs of Philly. I wanted to recreate<br />

what it felt like sitting out with them on<br />

warm summer nights, gathered with<br />

aunts, uncles, cousins and friends. I<br />

wanted to bring to our home that feeling<br />

of security. Working with our friends at<br />

Serena & Lily, we started on the journey<br />

to make our front porch more than just<br />

a couple of rocking chairs looking out on<br />

our street, but instead, a communal space<br />

fit for gathering together.<br />

We imagined the porch as a living<br />

area, bringing in a Moroccan-inspired<br />

outdoor rug, seagrass pillows and a<br />

Bamileke table that can withstand weather<br />

conditions. Creating a floor plan that<br />

allows guests to sit and chat around the<br />

table, or sit to the side and enjoy views of<br />

the garden, we created a space where we<br />

can gather with family and friends and talk<br />

all night, until even the fireflies go to bed.<br />

As we moved to designing the back<br />

of the home, that feeling of security<br />

became more and more of a factor. Those<br />

summers as a child, I had no cares. I was<br />

free and unencumbered by the world. But,<br />

The Black Family Home is an<br />

ongoing series focusing on the<br />

history and future of what home<br />

means for Black families.<br />

Stay tuned for the upcoming book<br />

from Penguin Random House.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Jeanine in the<br />

Celeste Kaftan,<br />

see page 23<br />

14 aphrochic

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

I’ve realized that the summer of 2020 left<br />

me feeling uneasy, particularly about<br />

going outside. While we loved seeing the<br />

BLM protests march by our apartment in<br />

Brooklyn, and we chanted and whistled<br />

support from our windows, a summer of<br />

seeing protestors be attacked by police;<br />

of hearing NYPD helicopters fly over our<br />

neighborhood for weeks; of late night firecrackers<br />

that sounded so close I thought<br />

the building would catch fire, I had become<br />

traumatized and outside didn’t feel so<br />

free anymore. I was constantly worried<br />

that we would do something “wrong”<br />

outside of the apartment and encounter<br />

an officer who might shoot us. I worried<br />

about walking down the street with my<br />

husband and that he might be mistaken for<br />

someone and be shot by the police. I was<br />

constantly worried that we would be the<br />

next victims of state-sanctioned violence.<br />

And that worry was also impacting how I<br />

thought about living in my own space.<br />

Reflecting on those feelings of uneasiness,<br />

and with the porch being a space for<br />

community, it felt important that the back<br />

of the home be designed as a place of solace<br />

— a place to be quiet; to rest and to heal.<br />

Again, we worked in partnership with<br />

Serena & Lily to find the right pieces to<br />

create that healing space.<br />

A cushy sectional was chosen to<br />

take center stage on the deck. Plump<br />

with pillows, it became the perfect place<br />

to sit and read a book at any time of day.<br />

Hurricane lanterns filled with citronella<br />

incense sticks were brought in to keep<br />

the bugs at bay and add a touch of indoor-style<br />

to the outdoor space. For the<br />

outdoor dining area we wanted something<br />

throwback and chose a 1970s-style wicker<br />

set. A collection of wood serving ware and<br />

chargers completed the aesthetic.<br />

Coming out of a year defined by the<br />

twin epidemics of COVID-19 and police<br />

violence, it’s been hard for me to feel completely<br />

safe outside. But, as we’ve worked<br />

on completing our outdoor space at our<br />

new house, I’ve realized how important it<br />

is to take up space, to be unafraid in doing<br />

so and to craft spaces that support and<br />

nurture us. Coming back outdoors has<br />

been so healing. I’m starting to feel like<br />

that kid again — loving the sunshine. And<br />

even though life may not be as carefree, I<br />

choose to make my own space where I can<br />

be free and soak up some rays. AC<br />

Outdoor Dining Area<br />

Pieces from Serena & Lily: Catalina Dining Chair $498, Pacifica Dining Table $2298, Cayman<br />

Glasses (set of 4) $48, Cayman Seagrass-Wrapped Pitcher $48, Kokkari Placemat $28, Salento<br />

Image of Jeanine and her best friend, age 4.<br />

Linen Napkins (set of 4) $48, Wood and Marble Serving Set $68, Rhinebeck Bowls $98, Woodbury<br />

Serving Board $128, Rhinebeck Serving Board $78, Millerton Footed Fruit Bowl $198<br />

16 aphrochic issue seven 17

THE BLACK FAMILY HOME<br />

Front Porch<br />

Pieces from Serena & Lily: Capistrano Tete-A-Tete $3298, Bamileke<br />

Outdoor Coffee Table $1998, Palisades Outdoor Chair $498, Whitehaven<br />

Rug $2298, South Seas Side Cart $498, Salerno Pillow Cover $88, Madrona<br />

Pillow Cover $158, Venice Rattan Chair $498, Natural Blue Woven Fan from<br />

Reflektion Design $30<br />

Back Deck<br />

Pieces from Serena & Lily: Sundial Outdoor Slipcovered Sectional<br />

$9498, Bamileke Outdoor Side Table $798, Del Mar Cotton Throw<br />

$168, Montecito Floor Pillow $228, Verano Tray $58, Summerland<br />

Lantern $178<br />

18 aphrochic issue seven 19

MOOD<br />

SOULFUL SUMMER<br />

It’s summertime and we’re embracing all that is simply<br />

beautiful. Easy silhouettes for lounging in. Handcrafted<br />

items that are perfect for alfresco entertaining. A<br />

restful palette of greenish-blues and lush corals that<br />

reflect both the water and the sun. Here are our musthave<br />

pieces that will help you create the most stunning<br />

retreat at home this season.<br />

KIDA Hanging Lounge<br />

Chair by Stephen Burks,<br />

inquire for pricing<br />

dedon.de<br />

Curve Mug in Rosewater $42<br />

tellefsenatelier.com<br />

Hand Dipped Beeswax Taper Candle<br />

Half Dozen $36<br />

alysiamazzella.com<br />

100% Linen Sheet Set in Sage $269<br />

linoto.com<br />

Natural Blue Woven Fan $35<br />

reflektiondesign.com<br />

20 aphrochic issue seven 21

MOOD<br />

Amur Wall Sconce in<br />

Copper $750<br />

perigold.com<br />

rayo & honey canvas<br />

pennants $75<br />

rayoandhoney.com<br />

Goodee Teal Pillow $149<br />

goodeeworld.com<br />

Caribe Plis Kann Wallpaper $72<br />

ze-haus.com<br />

Celeste Kaftan in Shell $225<br />

sanctuairelife.com<br />

22 aphrochic issue seven 23

FEATURES<br />

Transformation, Rebirth, and Re-Emergence | Family Ties | Lit! |<br />

History on the Menu | The Goodtime Hotel | Brunch with Purpose |<br />

Talking Points | Celebrating Our Sound

Fashion<br />

Transformation<br />

Rebirth, and<br />

Re-Emergence<br />

HARBISON is reborn<br />

2021 has been the story of our comeback as a society,<br />

our re-entry into the world, and for many, embracing<br />

a whole new way of being. We have gone through this<br />

collectively as individuals and there are even some<br />

brands that have also taken a breath and transitioned<br />

during this time. HARBISON is one of those brands.<br />

Interview by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos by Dan Dealy and Lee Morgan<br />

26 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

Five years ago, Charles Harbison was<br />

everywhere. He was a favorite designer<br />

of Beyoncé, Solange, and Michelle. He<br />

had been featured by coveted fashion<br />

magazines and was in the spotlight<br />

at New York Fashion Week. And then<br />

suddenly, he was gone, relocated from<br />

New York to Los Angeles, and placing the<br />

brand on an indefinite hiatus.<br />

In late 2020 came an announcement<br />

on his Instagram, he would be designing<br />

a sustainable line for Banana Republic in<br />

partnership with Harlem’s Fashion Row.<br />

HARBISON was back on the scene and<br />

fashion-lovers were thrilled. Since that<br />

announcement, HARBISON has been<br />

preparing to launch an A/W21 collection,<br />

is expanding its capsule with Banana<br />

Republic, and was honored by the CFDA.<br />

AphroChic <strong>Magazine</strong> editor, Jeanine<br />

Hays, sat down with Charles to talk<br />

about lessons learned in absence, the<br />

importance of valuing ourselves, and<br />

honoring the “her” in us all.<br />

JH: Congratulations on the relaunch<br />

of HARBISON! Why is now the<br />

right time to start this new chapter?<br />

CH: Damn, this is a good question. I<br />

think now is the right time because I have<br />

the right perspective. It's been, what, five<br />

years? Which is funny, because it's longer<br />

than HARBISON actually existed in New<br />

York. But it's taken that amount of time<br />

for me to get my footing in a new place, to<br />

reconfigure my perspective into one that<br />

is more honoring of myself, that is more<br />

self-protective. And then I think there<br />

are some ideas that I was navigating<br />

in the beginning stages of HARBISON<br />

that needed some maturation. And then<br />

these years “away,” have had me working<br />

for brands at different levels, working<br />

abroad in Europe, and working across<br />

different product categories. So all of<br />

this expansion has refined my design<br />

perspective and I think the years away,<br />

reminding and refining my self-sustaining<br />

nature, has renewed my personal<br />

perspective. It's coming together in a<br />

way that I think aligns with a time where<br />

people are willing to listen to ideas that<br />

I was navigating back then, but in a way<br />

that is a bit more primed now, through<br />

product and through fashion.<br />

JH: Fashion can feel really forced a<br />

lot of the time. As if everyone's always<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

32 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

forcing it to be cool, whether or not it actually is. But when I<br />

saw you start putting out the first images of the new line on<br />

Instagram, it felt really magical. It felt organic and very unforced.<br />

And a lot of it surrounded this concept of “her” that seems to be<br />

very much at the center of it all. So who is “her” in this collection?<br />

How are you defining that and how does it work as connection<br />

point for your audience?<br />

CH: The great thing about that pronoun is that, as we are<br />

navigating a world that is less binary, less gendered in general,<br />

the ideas around pronouns are just far more expansive. So there<br />

are a few different answers. My primary “her” is always my<br />

mom and those matriarchs that taught me about beauty, who<br />

showed me its complexity and evolution, and how to use it as a<br />

tool. Also, because the “her” in me is reflective of their “her,”<br />

the years of understanding and nurturing those places in me<br />

that are softer, more nurturing, and more feminine, have really<br />

helped round out my design perspective and my experience<br />

as a human in the world. And when I do that for myself, I'm<br />

much better at doing that for my customer base. Beyond that,<br />

the “hers” in my life, the women, the people, peers, I find so<br />

inspiring just watching them live, watching how they navigate<br />

oppression in such a beautiful way. Seeing them be women in<br />

the world, navigating misogyny and sexism, without sacrificing<br />

those parts of themselves that the oppression targets. And then<br />

the earth, which is kind of this newer priority for me. Coming<br />

to Cali really helped remind me of who I am as a country boy<br />

and loving the earth and seeing the earth as my first canvas,<br />

my first playground. It's wonderful to remember the earth as<br />

the first and primary resource that we have and prioritizing<br />

it. It is not just cute, it is imperative. So it's all of those “hers”<br />

collectively. And I think I just noticed I was habitually aligning<br />

myself with the feminine. So I just made it a concrete decision,<br />

one that’s to the benefit of every customer.<br />

JH: You studied architecture and textile design. How does<br />

that fit in to your fashion aesthetic and what you're creating now?<br />

CH: Studying architecture was one of the most important<br />

foundational things that I did. I didn't complete my degree in<br />

it because midway through I found that the tactile nature of<br />

textiles gave me a sense of joy and immediacy in the process<br />

of design that I adore, and the long lead of architecture was<br />

just something that wasn't quite right for me then. But what<br />

architecture represents is just my love of building things, of<br />

constructing things or configuring things. And that's how<br />

I approach fashion. It is building. I love the challenges of<br />

construction. I love when I have an aesthetic idea, and then<br />

working backward to figure out how do we actually build this<br />

thing? That really excites me and it shows up in my work, in<br />

construction but also in textile design, and everything. Textiles<br />

and fibers become the bricks I use to build dresses or suits or<br />

whatever it is. And I love all of it. That's why I comprehensively<br />

adore the process of fashion design.<br />

JH: We’ve spoken at a number of schools and met with Black<br />

students who were studying architecture, and they were having<br />

a really tough time. In many cases we found that the school was

Fashion<br />

telling them that there was no such thing<br />

as a Black architectural perspective,<br />

really trying to beat into them that their<br />

perspective was irrelevant to “real”<br />

architecture. What was it like for you<br />

studying architecture as a Black man? Was<br />

it also constraining? And is fashion less so?<br />

CH: One-hundred percent. That<br />

was it in a nutshell. It did feel early on<br />

as if architecture required some sort<br />

of removal of identity and personal<br />

aesthetic. I didn’t feel that when I began<br />

painting and then moving into fiber arts.<br />

For one of the first projects I took on<br />

when I transitioned from architecture<br />

to textile science, I was on the loom for<br />

17 to 20 hours a day, weaving yards of<br />

fabric. And when I took this fabric, and<br />

started creating forms on the body I felt<br />

I was really trying to work through my<br />

indigenous heritage, trying to find some<br />

way to connect to that age-old process<br />

of weaving on a loom, and applying those<br />

textiles to the body in ways that were<br />

reflective of me. So it's interesting to see<br />

that the freedom of those curriculums<br />

showed up immediately in ways that<br />

affirmed my cultural identity in a way<br />

that I never was able to remotely process<br />

early in architecture.<br />

JH: Congrats on winning Banana<br />

Republic’s design competition. It sounds<br />

really exciting. How did the collaboration<br />

between Banana Republic and Harlem's<br />

Fashion Row come together? And what<br />

are the goals for you in terms of this<br />

collaboration with them?<br />

CH: So I think Harlem's Fashion<br />

Row and Gap Inc. had been working to<br />

establish a greater partnership. And<br />

then with Banana Republic, they decided<br />

to hold a competition, looking for a<br />

designer with whom to create a capsule<br />

collection of sustainably-thoughtful<br />

pieces. And it's hilarious, because it all<br />

happened in such a weird way. I don't do<br />

competitions because I have lost a lot<br />

of them. And my perspective on losing<br />

them unfairly isn't based on ego, it’s<br />

based on judges coming to me, telling<br />

me about backroom deals and loyalties,<br />

people on the judging panel pulling<br />

rank and all kinds of stuff. So one of<br />

the things I decided when I decided to<br />

leave New York was that I would never<br />

compete again. But this felt different. It<br />

was being led by Harlem’s Fashion Row,<br />

and I have so much respect for Brandice,<br />

who has been an advocate for us for<br />

years. So I knew that that piece of trauma<br />

that I experienced for years wouldn't<br />

be present. And Banana Republic is an<br />

entity that I relate to. I worked there<br />

for a while in undergrad. The idea of<br />

attainable luxury is something that I<br />

adore and Banana does it in a way that<br />

gets into people's hands quickly. And<br />

sustainability was a central component.<br />

So I submitted my application and<br />

I didn't think anything else of it. I was<br />

happy that I had decided to do it, and for<br />

me, it felt like I was getting my muscle<br />

back, as if doing this was taking the step<br />

forward and HARBISON would be in<br />

the near future. And then I got a couple<br />

callbacks. And I didn't say anything<br />

different from what I've always said.<br />

And I didn't really even prepare. It was<br />

incredibly authentic, incredibly organic.<br />

And I stuck to the things that I love, and<br />

our approach to sustainability, which is<br />

not just environmental sustainability,<br />

but also personal sustainability, and<br />

cultural sustainability, and needing all<br />

three of those components to be present.<br />

And they loved it. The collection was<br />

supposed to be 3-5 pieces when it was<br />

announced in Vogue in <strong>No</strong>vember 2020.<br />

<strong>No</strong>w we're up to 20 pieces and the size<br />

range has expanded to go from zero<br />

up to 22. It is a capsule of pieces that I<br />

just find really, really comfortable and<br />

fun and desirable and thoughtful. And<br />

it's a really nice way to reintroduce<br />

myself to the industry, because it does a<br />

thing that I couldn't do before, which is<br />

make pieces more democratic and more<br />

accessible. I'm happy about it and the<br />

Banana team is great.<br />

JH: So on top of everything else<br />

you’ve just been honored by the CFDA,<br />

which is like the ultimate moment of<br />

36 aphrochic issue seven 37

Fashion<br />

recognition for a designer. How are you<br />

processing this moment?<br />

CH: For the four years that we were<br />

doing collections, made Fashion Week, had<br />

incredible celebrity endorsements and press<br />

articles, print, digital, everything, I had no<br />

relationship with that entity, which was in<br />

essence the mother of fashion in New York.<br />

Then all of a sudden all these years later, they<br />

just show up. And for us, we just wanted to<br />

know why. And when I talked to Lisa Smilor, it<br />

was really an amazing conversation because<br />

she acknowledged all of those things. And<br />

even after that conversation, I was honestly<br />

prepared to walk away. I let them know that<br />

if this comes with strings attached, I don't<br />

want it. I would rather navigate life with a<br />

tight budget and our agency intact rather<br />

than take on a grant that would force us to<br />

have to defer to an entity that my trust in had<br />

waned. But the response was that this is for<br />

you to spend in the way that you find most<br />

profitable for your business. So it feels right.<br />

And I'm grateful. And I'm excited. And it's<br />

coming at a time where we all need it. But it's<br />

also nice to know that we genuinely deserve<br />

it. And being able to say that and know that<br />

it's coming from a place of humility, but also<br />

from a place of knowing your value, which<br />

is central to the experience of Black people<br />

in every industry. It’s very, very important<br />

for Black creatives, because we do navigate<br />

systems and dynamics that are inherently<br />

racist. And so in order to persist, and to be<br />

tenacious, you have to go back to that mirror,<br />

you have to go back to your drawing board,<br />

and look at your work daily, and know that<br />

it is better than what they are trying to tell<br />

you it is. If we stay true to our crafts and the<br />

reasons why we do them, eventually they<br />

catch up. AC<br />

38 aphrochic

FAMILY<br />

TIES

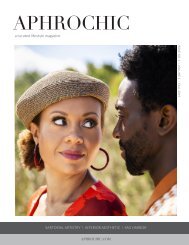

Interior Design<br />

A Brooklyn Brownstone Where<br />

Family Is The Heart of the Story<br />

A Brooklyn brownstone with good bones, a family of seven in need of a space<br />

that promotes togetherness, and a blending of cultural heritages. These are<br />

the elements that were in the brief when we began working with our clients,<br />

Jodi Querbach and Kemis Lawrence, on the design of their home. The couple<br />

led a busy life. Jodi, an executive for one of Brooklyn’s oldest non-profits, and<br />

Kemis, a development chef for some of the city’s hottest new restaurants. Their<br />

five children, three of whom were very energetic young boys, also had a lot of<br />

activities as well. This was a family in need good design that offered relaxation<br />

and togetherness.<br />

Interior Design by AphroChic<br />

Photos by Patrick Cline<br />

Styling Assistant Tanika Goudeau<br />

Photography Assistant Chinasa Cooper<br />

Words by Bryan Mason and Jeanine Hays<br />

42 aphrochic

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

Sometimes it feels cliché to say that design matters. But<br />

good design has the ability to accomplish so much. It can meet<br />

your needs, it can help reshape your environment, and it can<br />

serve a purpose. For Jodi and Kemis, we wanted this space to be<br />

a retreat for them. Immediately calming when they walked in<br />

the front door, and relaxing for the kids as well. A place where<br />

they could gather around the TV or eat dinner as a family after<br />

some very long days in the city.<br />

We began with color. Kemis is an unabashed fan of his<br />

Jamaican heritage. When we first entered the home, a Jamaican<br />

flag was hung on the living room wall. And while we love Jamaica<br />

too (we got married on the cliffs in Negril), we wanted to find<br />

a way to bring the island home without being too literal. We<br />

reflected on our own time in the country, and what we loved<br />

most about Jamaica. One of the best moments for us was<br />

watching the sunsets on the island. Watching the sun go down,<br />

it looked as if it was falling into the ocean. Some nights there<br />

would be a lilac hue in the sky that was magical. We brought<br />

that lilac feeling in, working with a full-spectrum paint that was<br />

gray in the morning light, but as the sun went down in Brooklyn,<br />

became more lilac at night, echoing those magical sunsets. The<br />

effect was immediately relaxing.<br />

To keep with the island theme, woven pieces were brought<br />

in to the home. Beneath the dining table, that now could easily<br />

seat the whole family for dinner, a seagrass rug was brought<br />

in. On the built-in bookshelves, woven baskets were placed as<br />

storage for each boy’s toys and accessories. Among the mix of<br />

island-inspired pieces, we brought in a collection of artisan<br />

pottery and metallic sculptures, a nod to Jodi’s love of contemporary<br />

farmhouse style.<br />

We had also met our objective. The living room could<br />

easily seat 6-8 people, with a new sectional sofa and leather<br />

swan chairs that the kids immediately loved. We designed a new<br />

fireplace surround with our contractor, Will Johnson, and it<br />

became the perfect entertaining unit for when the boys want to<br />

watch TV or play video games.<br />

<strong>No</strong> home is complete without art, and we brought two<br />

special pieces into the space. A limited edition print from<br />

Tappan Collective, Palm Shadow 2 by David Kitz, was a nod to<br />

Jamaica. And in the dining room, we worked with the Jenn<br />

Singer Gallery to secure Gold #2 by local artist, Valincy-Jean<br />

Patelli. Valincy lived just around the corner, and was able to<br />

bring the piece over and meet the family. A thrill for everyone!<br />

Good design matters. It can bring a family joy. It can<br />

promote togetherness. It can help a family tell their story. As<br />

one of the kids said when he stepped into the finished project,<br />

“this is paradise on world tour!” We are thrilled we could create<br />

a paradise that they can enjoy for years to come. AC<br />

46 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

48 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

“Good design matters. It<br />

can bring a family joy. It can<br />

promote togetherness. It can<br />

help a family tell their story.”<br />

50 aphrochic

Culture<br />

Lit!<br />

An Excerpt from After The Rain: Gentle<br />

Reminders for Healing, Courage and Self-Love<br />

by Alexandra Elle<br />

In her latest book, After The Rain, author and poet, Alexandra Elle takes us on a<br />

journey. It is all at once her journey and ours, as Alexandra shares her personal<br />

stories of love, loss, acceptance, and healing, delivering lessons that can help you<br />

move from self-doubt to self-love. The book, divided into 15 life lessons on change,<br />

identity, learning to breathe, soothing suffering and so much more, is filled with<br />

meditations that you’ll find yourself coming back to again and again as you chart<br />

your own path to self-discovery and self-care. After The Rain also has a beautiful<br />

companion piece, the In Courage Journal, that offers daily practice in self-care.<br />

Photos by Erika Layne<br />

52 aphrochic

Culture<br />

Loving yourself isn’t always<br />

a beautiful process.<br />

It’s hard.<br />

It can break you open.<br />

It can wear you down.<br />

Self-love is birthed in the<br />

trenches of our darkest moments —<br />

that’s why the light feels so good<br />

when we finally find it.<br />

Learn more about Alexandra’s work, her upcoming workshops and books at alexelle.com<br />

54 aphrochic issue seven 55

Food<br />

History on<br />

the Menu<br />

The Magnolia House Serves Up<br />

the Past to Preserve Its Future<br />

On Feb. 1, 1960, four students from <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina<br />

Agricultural and Technical State University<br />

sat down at a Woolworths' “whites only” lunch<br />

counter and began a movement that spread<br />

around the country. That one history-changing<br />

act also put Greensboro, N.C., on the map.<br />

But for decades before that sit-in, Greensboro<br />

was already “on the map” for many Black artists,<br />

entertainers, and families who consulted the<br />

iconic Green Book for a safe harbor for the night.<br />

Words by Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Photos from Magnolia House<br />

56 aphrochic

Food<br />

Built in 1889 and listed in<br />

the National Register of Historic<br />

Places, the Historic Magolia<br />

House was originally a family<br />

home in the South Greensboro<br />

Historic District. Around WWII,<br />

the Gist family purchased the<br />

home and opened it in 1949 as an<br />

inn for Black travelers who were<br />

not allowed to stay in other segregated<br />

hotels and motels.<br />

The Historic Magnolia<br />

House was listed in the famous<br />

Green Book, named for founder<br />

Victor Hugo Green. The Green<br />

Book listed establishments<br />

across the country that were safe<br />

for African Americans to sleep<br />

and to eat as they traveled.<br />

Magnolia House was<br />

included in the Green Book as<br />

late as 1968, and played host<br />

to famous guests like James<br />

Baldwin, Carter G. Woodson,<br />

Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson,<br />

Ray Charles, Duke Ellington's<br />

Band, Ike and Tina Turner, and<br />

Louis Armstrong. It is one of<br />

only six Green Book inns still in<br />

operation in <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina.<br />

After the '70s, the house fell<br />

into disrepair and in 1995 Samuel<br />

Pass bought the house from the<br />

Gist family with a plan to restore<br />

it and create a museum to honor<br />

its past. His daughter Natalie<br />

Pass Miller is now the owner and<br />

manager of the historic property.<br />

And to fund that restoration,<br />

Natalie Pass Miller has<br />

created another way to use<br />

history to create a future for The<br />

Magnolia House with a Shoebox<br />

Lunch.<br />

"With the Pandemic, much<br />

like other museums and organizations,<br />

we had to close our doors<br />

to the community. The Magnolia<br />

Shoebox Lunch was created as a<br />

way to bring Black history and<br />

education to the community's<br />

doorstep," she says.<br />

"Everything we do is intentional<br />

to replicate the Green Book<br />

and history of the Negro Traveler.<br />

All of the services we offer are<br />

that of what the Gist family<br />

offered during the '50s and '60s.<br />

The Shoebox Lunch was a critical<br />

survival tool of Negro Travelers<br />

during Jim Crow that provided<br />

a meal in the event there was no<br />

Green Book stop on their route.<br />

With that being an important part<br />

of history, we created the box<br />

and programming to honor the<br />

tradition, provide education, and<br />

a tool that fosters dialogue within<br />

our community," she explains.<br />

The Shoebox Lunch is in<br />

an actual shoebox that's been<br />

adapted to deliver delicious food.<br />

Popular items inside the box<br />

include Fried Chicken, Bombay<br />

Toast, and Fish N Grits, as well<br />

as a classic Shoebox pound cake<br />

slice.<br />

But Pass Miller says she also<br />

serves up a side of history. "We<br />

deem Magnolia's Shoebox Lunch<br />

as 'history in a box,' because we<br />

provide Black history education<br />

on the box as a way to support and<br />

foster family and school dialogue,<br />

while at the lunch table."<br />

In addition, the Magnolia<br />

House is offering brunches<br />

during the week. "Music and the<br />

Arts are an important part of<br />

our programming as it is part of<br />

rich history within the walls of<br />

Magnolia and the historical guest<br />

list," Pass Miller says. "When<br />

guests such as Louis Armstrong<br />

would stay with us for three<br />

weeks at a time, of course Mama<br />

Gist would provide meals for<br />

them. In honor of that we offer a<br />

Smooth Jazz Brunch."<br />

The House also operates as<br />

a museum with both permanent<br />

and temporary exhibits, as well<br />

as meeting spaces and other programming.<br />

The focus of both food-centric<br />

programs and business programming<br />

is to raise funds to<br />

help in The Historic Magnolia<br />

House's transformation. The<br />

goal is to create a boutique hotel<br />

that is a "100% replica of the 1949<br />

Green Book Hotel both structurally<br />

and operationally," Pass<br />

Miller says.<br />

To learn more about its<br />

history, or to make a donation, go to<br />

thehistoricmagnoliahouse.org.<br />

58 aphrochic issue seven 59

Food<br />

Cooking to Connect to Memories<br />

Natalie Pass Miller's Aunt Linda has been a staple to Magnolia's Black<br />

culinary experience. Known to the rest of the world as Linda Aamal Kite, she is a<br />

chef, food scientist, and seasonal fruit specialist. Here is her take on why food is<br />

so critical to the African American story, why you should never trust 15-minute<br />

collards, and three recipes she swears by.<br />

“Food has always been celebratory for Black people because we didn’t<br />

have a whole lot to celebrate. But we found a way. There’s this whole back story<br />

before it gets to the plate. A lot of these foods were considered trash. What we<br />

had to do is make do with what we could find and put together.<br />

"For example, collards are very nutritious and very filling. But you have to<br />

be very patient with them because it takes a long time to cook. My mother would<br />

say that we eat collards after the first frost. And I would say: 'Mama, why is that?'<br />

And she said, 'Well, they’re more tender.'<br />

"Well, lo and behold, the collard plants produce a natural enzyme when<br />

it’s cold and, consequently, it’s a natural tenderizer! You can’t overcook a<br />

collard green. So how do you know it’s ready? When it’s really tender and it<br />

almost melts in your mouth, that’s when you know it’s ready.<br />

“Anytime that someone tries to convince you that you can cook collard<br />

greens in 15 minutes….run. It takes time and a lot of patience.<br />

"In the end, cooking anything brings me closer to my family, because with<br />

these hands (her hands)...my mama is still here. So it’s a spiritual experience for<br />

me. I’m standing on my grandmother’s shoulders. I’m standing on my mama’s<br />

shoulders.<br />

"When you think about where we’ve come from…but we still have a long<br />

way to go. The difficulties that we’ve had as a people, somehow we could always<br />

use food as a distraction. <strong>No</strong> matter how hard things were, you come together<br />

around a plate of food that has been soulfully and lovingly prepared for you, it<br />

would make everything ok. <strong>No</strong> matter what.”<br />

Natalie Pass Miller on the front porch of The Historic Magnolia House in Greensboro, N.C.<br />

Hoppin’ John<br />

Cook 3 slices of bacon (traditional, beef, or<br />

turkey) until crispy and drain on paper towel.<br />

Sauté onion with chopped red and green<br />

peppers. Then add 2 cans of black eyed peas<br />

and heat thoroughly. Stir in about 2 cups of<br />

rice and crumbled bacon.<br />

Garnish with the tops of green onions for<br />

serving.<br />

Sweet Potatoes<br />

Bake sweet potatoes in a 400-degree preheated<br />

oven for approximately 45 minutes, depending<br />

on size. Sweet potatoes should be thoroughly<br />

washed, dried, and oiled prior to baking.<br />

Once cooked, slice sweet potatoes diagonally<br />

and set aside.<br />

For the sauce, heat 1 cup orange juice. Once<br />

heated, add ½ cup light or dark brown sugar<br />

mixing with butter or preferred fat, (i.e., olive or<br />

coconut oil). Stir in cinnamon, vanilla, and rum<br />

extract at the end. Heat until just boiling, simmer<br />

to reduce a little bit.<br />

Toss sweet potatoes in sauce and coat thoroughly.<br />

Collard Greens<br />

Stem collards. Stack, roll, and cut collards to your<br />

liking. Wash collards 6-8 times, or until water<br />

runs clear (to rinse off any grit).<br />

In a stock pot add oil, enough to cover the<br />

bottom of the pot. Sauté some onions until translucent.<br />

Add chopped garlic and sauté.<br />

Add collards, stirring down until all the greens<br />

are added to the pot. You will see liquid from the<br />

greens as they reduce in the pot. This is when<br />

you add whatever stock of choice or water, just<br />

enough to cover the greens about 2 inches, along<br />

with your seasonings.<br />

Be patient as collards take quite a while to cook.<br />

Depending on the amount of greens, start with<br />

45 minutes to an hour over medium-high heat.<br />

Cooking time should be adjusted for gas. Gas<br />

cooks quicker!<br />

62 aphrochic issue seven 63

The Goodtime Hotel

Travel<br />

A Feel-Good<br />

Destination in Miami<br />

Pharrell Williams and Partner David Grutman<br />

Open A Pastel Paradise in South Beach<br />

It’s no question that pink is a smile-inducing color, and Miami’s<br />

new The Goodtime Hotel will have you smiling from the moment<br />

you enter. Everything from the blushing pink-and-peach Library,<br />

where you can enjoy coffee, cocktails and casual meet-and-greets,<br />

to the private cabanas that extend the color palette, have been<br />

designed with happy pursuits and relaxed escapism in mind.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Images from The Goodtime Hotel<br />

66 aphrochic

Travel

Travel

Travel<br />

From the moment you step into this tropical oasis that blends<br />

mid-century Caribbean style, with Miami’s Art Deco past and today’s<br />

modern pastel palette, you are ready to relax and enjoy.<br />

“We want The Goodtime Hotel to impart a feeling of both revitalization<br />

and that rare, exciting thrill that takes over when you discover<br />

something special,” says Williams of his new hotspot that just opened<br />

this spring in South Beach. Overlooking Biscayne Bay on one side and<br />

the Atlantic Ocean on the other, it’s the kind of place built with Instagram-worthy<br />

views in mind, and a host of cool furnishings that<br />

will help you capture that perfect shot. “It’s that adrenaline-fueled<br />

sensation of entering a whole new setting and a whole new mindset.<br />

This place will provide a natural good time, for all who come through.”<br />

Williams, who has always known how to bring his audience joy<br />

through songs like Happy and his books Places and Spaces I’ve Been<br />

and A Fish Doesn’t Know When It’s Wet, has worked in partnership with<br />

Grutman to bring sunshine-seekers into a beautifully curated oasis<br />

where everyone can experience a good time. You can enjoy beautiful<br />

appointed rooms where the bathrooms feature that oh-so-trendy<br />

pink brick tile, cozy upholstered beds and cool leopard print benches.<br />

And when venturing further into the hotel, experience cocktails at the<br />

stylish pool bar or just hang in the lobby that looks like the living room<br />

of many of our dreams.<br />

With so much fun to be hand inside the hotel, decorated by the<br />

iconic Ken Fulk, you can’t forget that you’re also in Miami, where everywhere<br />

you venture there’s something fun to experience. Enjoy the<br />

nightlife, or take in an artistic tour of the Wynwood Walls to complete<br />

your trip to Florida’s newest destination. AC<br />

You can book your stay at thegoodtimehotel.com.<br />

72 aphrochic

Travel

Travel<br />

76 aphrochic issue seven 77

Travel<br />

78 aphrochic

Entertaining<br />

Brunch With<br />

Purpose<br />

Estelle Colored Glass Hosts A Stunning Fête To<br />

Support Local Food Purveyors in Charleston<br />

Stephanie Summerson Hall is the founder of Estelle Colored Glass, a luxury<br />

brand of colored glassware that’s handmade by artisans in Poland. Jewel-tone<br />

stemware, decanters and cake stands are all part of Stephanie’s collection<br />

that has a cult following. Oprah, Hoda and Martha are fans.<br />

To celebrate the launch of her new line of mint green martini glasses,<br />

Stephanie had an idea. She would host a casual brunch showcasing her new<br />

collection, and would include local bakeries and restaurants. “I like living in<br />

a community that is unique and so much of that uniqueness comes from the<br />

local restaurant and food purveyors in the community.”<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Photos from Estelle Colored Glass<br />

80 aphrochic

Entertaining<br />

The timing of such an event could not have been more perfect,<br />

as restaurants around the country are beginning to reopen, but<br />

are struggling with business due to the slow-down caused by the<br />

pandemic. A casual brunch was arranged at the Dewberry Hotel in<br />

Charleston, South Carolina. Glassware, cake stands and decanters<br />

from Estelle were used to create a fresh green and yellow color<br />

palette. Foods from the local community complemented the theme.<br />

“The pastries and croissants came from my neighborhood<br />

bakery, the Rustic Muffin,” Stephanie explains. “The pound cake was<br />

made by my neighbor three doors down. I love supporting her homebased<br />

bakery, Sunny Park Cakes. The dozen assortment of handmade<br />

biscuits came from Callie’s Hot Little Biscuit which has an eatery on<br />

King Street in Charleston and happened to be around the corner<br />

from our brunch location at the Dewberry Hotel. And expertly crafted<br />

offerings from Red Hot Clay Sauce - another Charleston-based<br />

brand - were added to our condiments table.”<br />

The launch of a new collection became the celebration of<br />

local community. What could be more beautiful? “I support [local<br />

purveyors] every time I get a chance and encourage you to do likewise<br />

in your own communities. These businesses thrive with our dollars<br />

and we need the authentic feel and goodness they add to our quality<br />

of life.” AC<br />

84 aphrochic

Reference<br />

Talking Points<br />

A Critical Race Theory Primer<br />

When it comes to starting a fire in this country, it seems<br />

all it takes is three words. If the words acknowledge the<br />

existence of white supremacy, the oppression of Black<br />

people, or propose meaningful steps towards a world in<br />

Photo by “cottonbro” from Pexels<br />

which neither exist, the reaction is immediate, visceral and<br />

widespread. In the last few years, words like Black Lives<br />

Matter, I Can’t Breathe, or Know Your Rights, have been at<br />

the center of firestorms of white outrage that have erupted<br />

from every right-wing outlet, spilling from the mouths of<br />

every conservative pundit to be repeated ad nauseam, often<br />

becoming larger and less accurate with every telling. The<br />

most recent triptych of words to be used by conservative<br />

media and lawmakers to stoke the ire of their constituencies<br />

is Critical Race Theory, or CRT.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Chances are you’ve seen it in the news<br />

recently as nearly a dozen states have either<br />

passed laws banning its teaching or are poised<br />

to do so. As the controversy rages on and the<br />

conversation becomes more about education,<br />

history, and the danger of harming white children’s<br />

sense of self-worth with an accurate recounting<br />

of American history, it’s becoming<br />

clear that there are many on both sides who<br />

aren’t entirely clear on what CRT is, where it<br />

comes from, or what it’s trying to do. So here is<br />

a very brief primer on Critical Race Theory and<br />

resources to help you be better informed.<br />

What Is Critical Race Theory?<br />

One of the main problems surrounding<br />

the current conversation on CRT is that<br />

many people seem to have it confused with a<br />

number of other things that it is not. Contrary to<br />

recent popular belief, CRT is not an approach to<br />

teaching, a version of history, or the 1619 project.<br />

It’s not a form of inclusivity, diversity, or sensitivity<br />

training. It’s not even a singular theory,<br />

as numerous scholars, authors, and academics<br />

have contributed to its development with<br />

varying points of emphasis.<br />

Though it has since spread to a number<br />

of other fields of study, CRT was originally a<br />

series of legal critiques viewing the American<br />

system of laws as the means by which racist<br />

power structures are codified, normalized, and<br />

enforced. It refutes the idea of colorblind laws,<br />

demonstrating that even laws ostensibly written<br />

to be race-neutral, such as sentencing laws<br />

for drug possession, can be applied in racially<br />

biased ways, resulting in disproportionate punishment<br />

for people of color and the reification of<br />

predetermined racial stereotypes.<br />

In this, CRT borrows from the older<br />

Critical Legal Studies, which is one of its main<br />

influences. This school of thought, which also<br />

focuses on the law as the codification of social<br />

biases, holds that the law and its applications<br />

are determined as much or more by political<br />

or ideological positions as they are by logic and<br />

legal reasoning. While this may seem obvious,<br />

for decades prevailing legal doctrine held that<br />

law and logic were the only pertinent factors in<br />

legal decision making.<br />

In arguing that American laws and the<br />

mechanisms through which those laws are<br />

enforced (e.g. police, courts, prisons) are<br />

primary support structures of systematic<br />

racism, CRT views the structures themselves as<br />

being inherently racist and in need of reform.<br />

At the same time, it advocates for the rule of law<br />

and acknowledges the great role that judicial<br />

and legislative progress has played in improving<br />

the lives of people of color. Yet it eschews Liberalism<br />

as a wholesale answer to the problems<br />

that it outlines, highlighting the frequency and<br />

facility with which liberal agendas co-opt or<br />

slow progressive racial movements, either redirecting<br />

their efforts for the benefit of white<br />

interests or allowing opportunities for conservative<br />

challenges and backsliding.<br />

The specific arguments and proofs offered<br />

within the confines of Critical Race Theory are<br />

far too numerous to list here. However some of<br />

86 aphrochic issue seven 87

Reference<br />

Photo by Darlene Alderson from Pexels<br />

its basic principles are:<br />

1. That racism is not a biological fact but a<br />

socially constructed set of categories designed<br />

to codify a specific set of power relationships.<br />

Therefore race is not real, but racism is.<br />

2. That racism is normal in American<br />

society. It is not an aberration, the exception to<br />

the rule or restricted to the thoughts and actions<br />

of a marginalized few. It is the daily lived experience<br />

of most, if not all, people of color in this<br />

country.<br />

3. The establishment and protection<br />

of racist power differentials is encoded into<br />

American society, enforced by its laws and<br />

expressed in its public policy. These structures<br />

normalize the habitually racist perspectives and<br />

processes of the country making them invisible<br />

or at least deniable.<br />

4. The process of legislative racial progress<br />

and regression in America — such as affirmative<br />

action or legalizing marijuana — is often manipulated<br />

to serve white interests. Simultaneously,<br />

actions designed to benefit whites are often<br />

branded as progress for people of color.<br />

5. Accurate and adequate representation<br />

is crucial. The same mechanisms of control<br />

which are used to ascribe negative stereotypes<br />

to people of color are used to deny our ability to<br />

speak accurately and meaningfully to our own<br />

experiences of racism in legal, political, and<br />

social settings.<br />

6. That humanity is intersectional and no<br />

one person can be fully described by their membership<br />

in a single group. Every person has a<br />

race, gender identity, ethnicity, sexual preference,<br />

etc., and their experience of society will<br />

be determined largely by the groups that they<br />

belong to.<br />

Where Did It Come From?<br />

Even though a lot of the controversy and<br />

anger around CRT seems very new, the idea<br />

itself started back in the 1970s and has roots<br />

that go back even further. Initially CRT grew<br />

in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement<br />

as scholars of color sought to understand why<br />

the gains of the movement were not resulting<br />

in the level of change they had anticipated and<br />

why many of those gains seemed under constant<br />

threat of being rolled back. Continued disparities<br />

in education following the Brown v. Board<br />

of Education case were of particular interest to<br />

Derrick A. Bell Jr., a legal scholar and the first<br />

tenured African American professor at Harvard<br />

Law School. Professor Bell’s analysis of postcivil-rights<br />

era America laid much of the foundation<br />

for what would become CRT. Equally<br />

impactful was his career which saw him lead<br />

several protests in response to student demands<br />

for more diverse faculty and leave several<br />

notable posts in protest over refusals to hire or<br />

promote qualified women of color as professors.<br />

In 1981, the year after Bell resigned his<br />

position at Harvard for the second time, then<br />

incoming student, now noted scholar, Kimberlé<br />

Crenshaw, organized with other students<br />

to arrange for 12 scholars to hold talks at the<br />

school around Bell’s work, “Race, Racism, and<br />

American Law.” In 1989, Crenshaw held the first<br />

workshop on the topic, calling it "New Developments<br />

in Critical Race Theory,” and is therefore<br />

credited with giving the discipline its name.<br />

Further, she is the architect and first<br />

positor of intersectionality, now an extremely<br />

widespread and influential concept. Since then,<br />

the field has both grown and diversified with<br />

additional scholars not only adding to the canon<br />

of what could now be termed core CRT, while<br />

others have created group specific interpretations<br />

including LatCrit (Latino-critical) and<br />

TribCrit (Tribal Critical) along with Queer-critical<br />

and Asian-critical approaches. Other<br />

highly notable founders of CRT include Richard<br />

Delgado, who was one of the scholars invited by<br />

Kimberlé Crenshaw to speak at Harvard, Mari<br />

Matsuda, a highly influential legal scholar and<br />

the first Asian American female law professor<br />

to gain tenure in the United States, and Patricia<br />

J. Williams, a noted scholar and professor<br />

who writes the column “Diary of a Mad Law<br />

Professor” for the Nation.<br />

Why They Scared?<br />

At its core, CRT is simply the realization<br />

that American laws and legal structures<br />

are deeply impacted by race in ways that shape<br />

every aspect of American life while obscuring<br />

the presence and effect of race as a determining<br />

factor. For anyone familiar with American<br />

history, the formation of early laws to enforce<br />

the rule of slavery, the crucial impact discussions<br />

over slavery had on the writing and ratification<br />

of the constitution, and the importance<br />

of equality movements at every stage in<br />

this nation’s development from abolition to<br />

suffrage to LGBTQIA+ rights and BLM, this is<br />

not an earth-shaking revelation. So why are<br />

there those who find it so terrifying that they<br />

are currently doing so much to criminalize even<br />

the discussion of what is in fact just a set of legal<br />

theories?<br />

This is a very good question, and one that<br />

is unfortunately beyond the scope of this article<br />

to answer. Better answers than any we might<br />

provide here are expectedly to be found in any<br />

Photo by Darina Belonogova from Pexels<br />

88 aphrochic issue seven 89

Reference<br />

of the books on CRT this article lists. We might<br />

also suggest the works of Patricia Hill Collins,<br />

Robert L. Allen, and any number of other Black<br />

sociologists who have dedicated themselves to<br />

this question. It’s a difficult question to answer<br />

because it’s both subjective and suppositional.<br />

As Black people we can’t truly know what<br />

motivates those who work tirelessly to ensure<br />

that we remain marginalized and disadvantaged<br />

in this society.<br />

What we do know is this: they are scared.<br />

Because after 2020 and a whole year of marches<br />

and BLM protests, people are listening and<br />

there’s a real opportunity for things to change.<br />

This fear is evident in any number of very visible<br />

ways. First, and most obvious is the whole idea<br />

of attempting to illegalize CRT in the first place.<br />

Using America’s laws to criminalize the conversation<br />

on how America uses its laws to criminalize<br />

Black people is the perfect example of the<br />

exact problem that CRT was created to address.<br />

Then there is the haphazard way in which CRT<br />

is being posited as a threat. As mentioned at the<br />

beginning of this piece, most of what’s being<br />

called CRT in conservative attacks against<br />

it, is not. Suddenly finding itself used as a<br />

euphemism for diversity, inclusivity training,<br />

gender sensitivity and inclusive history and<br />

pedagogy, CRT has seemingly become the repository<br />

for all of their fears, making it at once<br />

a bigger target and a way to kill many birds<br />

with one law. As usual, there is method to this<br />

madness. For a base driven by slogans and<br />

sound bites rather than facts, CRT is the perfect<br />

scary-sounding three-word antagonist to use<br />

to create exactly the groundswell of fear and<br />

loathing that has been seen and used to push<br />

through a series of vaguely worded, constitutionally-questionable<br />

laws.<br />

What’s At Stake?<br />

Still, however sloppy these moves on the<br />

part of conservatives might appear, they are incredibly<br />

calculated and extremely dangerous.<br />

You might find it ridiculous that these attempts<br />

at censorship are coming from the same people<br />

who have openly argued that hate speech is<br />

free speech, but it’s no more hypocritical than<br />

a cadre of slave owners listing liberty and the<br />

pursuit of happiness among humanity’s inalienable<br />

rights. And they never batted an eye. Just<br />

because a law should be challenged and struck<br />

down on constitutional grounds doesn’t mean<br />

that it will be. And vaguely worded laws can<br />

be used to enforce restrictions against a wide<br />

number of things not specifically outlined in the<br />

law itself. As the Atlantic’s Adam Harris reports,<br />

“The New Hampshire House of Representatives,<br />

introduced a bill that would bar schools [and]<br />

organizations that have entered into a contract<br />

or subcontract with the state from endorsing<br />

“divisive concepts,” [such as] “race or sex scapegoating,”<br />

questioning the value of meritocracy,<br />

and suggesting that New Hampshire — or<br />

the United States — is “fundamentally racist.”<br />

Citing the “fuzzy” language of other such bills,<br />

Harris cautions that these laws, while open to<br />

constitutional challenge as violations of the<br />

first amendment, will likely be used to censure a<br />

wide range of progressive educational and professional<br />

conversations on intersectionality,<br />

structural racism and diversity.<br />

What’s at stake here then, is ultimately<br />

our legal ability to openly take this society to<br />

task over issues of marginalization and disenfranchisement<br />

on the basis of race, gender,<br />

religion or any number of other grounds. What it<br />

requires of us is that we educate ourselves and,<br />

where possible, others; that we make ourselves<br />

heard through our votes and by using every<br />

platform at our disposal to make it clear that we<br />

will not be silent, complacent or placated; that<br />

we resist any and all attempts to steal from us<br />

the joy of legitimate victories like Juneteenth<br />

and Black Music Month which were not given<br />

to us but fought for and won; and that we keep<br />

the perspective that an honest and inclusive<br />

view of American history gives us: that we have<br />

never been what they say we are or been what<br />

they wanted us to be, that we have never given<br />

an inch in this fight and we see no reason to start<br />

now. AC<br />

A Critical Race Theory Book List<br />

Where is Your Body?,<br />

Mari J. Matsuda<br />

Words That Wound: Critical Race<br />

Theory, Assaultive Speech, And<br />

The First Amendment, Mari J.<br />

Matsuda, Kimberlé Crenshaw,<br />

Richard Delgado, Charles R.<br />

Lawrence III<br />

The Derrick Bell Reader, Richard<br />

Delgado & Jean Stephancic<br />

Faces at the Bottom of the Well,<br />

Derrick Bell<br />

Critical Race Theory: The<br />

Key Writings That Formed<br />

the Movement, Kimberlé<br />

Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary<br />

Peller, Kendall Thomas<br />

Critical Race Theory (Third<br />

Edition): An Introduction,<br />

Richard Delgado, Jean<br />

Stephancic & Angela Harris<br />

90 aphrochic issue seven 91

Sounds<br />

Celebrating<br />

Our Sound<br />

Music Icon Dyana Williams and the Importance<br />

of Recognizing the History of Black Music<br />

Dyana Williams is a Philly music legend. Actually, she’s a music<br />

legend everywhere, but if you’re from Philly (and we are), you not<br />

only know the name, you know the vibes. Arriving in Philadelphia<br />

after deejaying in her native New York and Washington D.C.,<br />

where she was known for a time as “Ebony Moonbeams,” Williams<br />

established the popular radio show “Love on the Menu” for radio<br />

station WDAS and later Soulful Sundays for Classix 107.9. The latter<br />

show lasting for 12 years before signing off for the last time in 2020.<br />

Interview by Bryan Mason and Jeanine Hays<br />

Vintage photos from Dyana Williams<br />

Photos of Dyana Williams by Caliph Gamble<br />

92 aphrochic

Sounds<br />

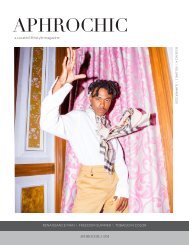

Even with her luminous on-air career,<br />

Dyana’s contributions behind the scenes have<br />

been even more impactful. Formerly married<br />

to music producer Kenny Gamble (Gamble &<br />

Huff), Williams has long been associated with<br />

the “Sound of Philadelphia” (Patti LaBelle,<br />

McFadden & Whitehead, Teddy Pendergrass,<br />

etc.) and has produced documentaries, founded<br />

and led organizations, and mentored countless<br />

emerging artists, a passion that she continues to<br />

pursue.<br />

But perhaps her most lasting gift to us is<br />

her role in the founding of Black Music Month.<br />

Its initial recognition in 1979 was the beginning<br />

of a process that Dyana would shepherd until<br />

it was written into law by congress and proclaimed<br />

first by President Bill Clinton in 2000<br />

and again by President Barack Obama in 2009<br />

and 2016.<br />

We were delighted to sit down with this<br />

icon of Philadelphia radio and tireless advocate<br />

for Black music culture to talk about the creation<br />

of Black Music Month, why it still matters, and in<br />

light of all that our community has endured in<br />

the past year, who she feels is making the music<br />

we need to keep us going right now.<br />

America just celebrated it’s 42nd Black<br />

Music Month this past June! We’re so excited to<br />

speak with you about the history of Black Music<br />

Month and how it came together because it’s<br />

such an amazing story and so important for us<br />

today. To start with, tell us about the Black Music<br />

Association. How did the organization come<br />

together and what was its purpose?<br />

DW: The Black Music Association<br />

was created by Kenny Gamble after a visit<br />

to Nashville Music City, which is known as<br />

a country music capital. And he felt that<br />

something could be done similarly in terms<br />

of organizing members of the music industry<br />

community to come together to show, not only<br />

our cultural contributions to America's indigenous<br />

music, but the economic impact of African<br />

American music throughout the world. And so<br />

the Black Music Association was established. It<br />

was a wonderful aggregation of radio personalities,<br />

artists, everybody from Stevie Wonder,<br />

Bob Marley, Dionne Warwick, Teddy Pendergrass,<br />

all of the artists of the day as well as the<br />

songwriters, producers, retailers, educators…It<br />

was just a wonderful entity of people who were<br />

like-minded and coming out of the creative<br />

culture of producing Black music.<br />

So that was the birth of the Black Music<br />

Association in 1978. Credit to Kenny Gamble,<br />

and a group of other people. I was a member.<br />

We were a couple at that time. We have three<br />

children and a six-and-a-half-year-old<br />

grandson now, but we, much like the two of<br />

you working together, Gamble and I did the<br />

same thing because we were committed to<br />

letting the world know that Black music isn't<br />

just to feel-good. It permeates every aspect<br />