LSB April 2022 LR

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

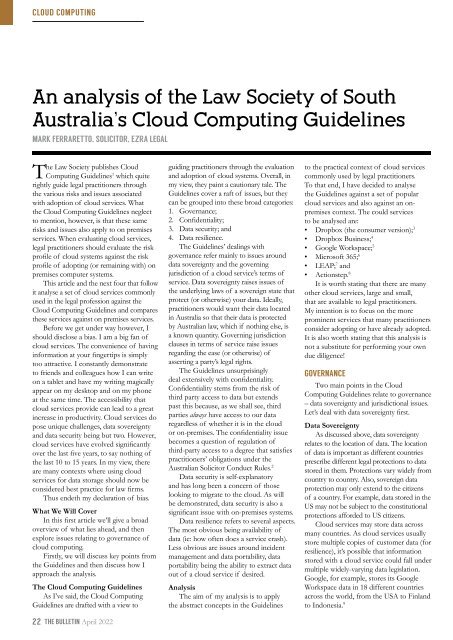

CLOUD COMPUTING<br />

An analysis of the Law Society of South<br />

Australia’s Cloud Computing Guidelines<br />

MARK FERRARETTO, SOLICITOR, EZRA LEGAL<br />

The Law Society publishes Cloud<br />

Computing Guidelines 1 which quite<br />

rightly guide legal practitioners through<br />

the various risks and issues associated<br />

with adoption of cloud services. What<br />

the Cloud Computing Guidelines neglect<br />

to mention, however, is that these same<br />

risks and issues also apply to on premises<br />

services. When evaluating cloud services,<br />

legal practitioners should evaluate the risk<br />

profile of cloud systems against the risk<br />

profile of adopting (or remaining with) on<br />

premises computer systems.<br />

This article and the next four that follow<br />

it analyse a set of cloud services commonly<br />

used in the legal profession against the<br />

Cloud Computing Guidelines and compares<br />

these services against on premises services.<br />

Before we get under way however, I<br />

should disclose a bias. I am a big fan of<br />

cloud services. The convenience of having<br />

information at your fingertips is simply<br />

too attractive. I constantly demonstrate<br />

to friends and colleagues how I can write<br />

on a tablet and have my writing magically<br />

appear on my desktop and on my phone<br />

at the same time. The accessibility that<br />

cloud services provide can lead to a great<br />

increase in productivity. Cloud services do<br />

pose unique challenges, data sovereignty<br />

and data security being but two. However,<br />

cloud services have evolved significantly<br />

over the last five years, to say nothing of<br />

the last 10 to 15 years. In my view, there<br />

are many contexts where using cloud<br />

services for data storage should now be<br />

considered best practice for law firms.<br />

Thus endeth my declaration of bias.<br />

What We Will Cover<br />

In this first article we’ll give a broad<br />

overview of what lies ahead, and then<br />

explore issues relating to governance of<br />

cloud computing.<br />

Firstly, we will discuss key points from<br />

the Guidelines and then discuss how I<br />

approach the analysis.<br />

The Cloud Computing Guidelines<br />

As I’ve said, the Cloud Computing<br />

Guidelines are drafted with a view to<br />

22 THE BULLETIN <strong>April</strong> <strong>2022</strong><br />

guiding practitioners through the evaluation<br />

and adoption of cloud systems. Overall, in<br />

my view, they paint a cautionary tale. The<br />

Guidelines cover a raft of issues, but they<br />

can be grouped into these broad categories:<br />

1. Governance;<br />

2. Confidentiality;<br />

3. Data security; and<br />

4. Data resilience.<br />

The Guidelines’ dealings with<br />

governance refer mainly to issues around<br />

data sovereignty and the governing<br />

jurisdiction of a cloud service’s terms of<br />

service. Data sovereignty raises issues of<br />

the underlying laws of a sovereign state that<br />

protect (or otherwise) your data. Ideally,<br />

practitioners would want their data located<br />

in Australia so that their data is protected<br />

by Australian law, which if nothing else, is<br />

a known quantity. Governing jurisdiction<br />

clauses in terms of service raise issues<br />

regarding the ease (or otherwise) of<br />

asserting a party’s legal rights.<br />

The Guidelines unsurprisingly<br />

deal extensively with confidentiality.<br />

Confidentiality stems from the risk of<br />

third party access to data but extends<br />

past this because, as we shall see, third<br />

parties always have access to our data<br />

regardless of whether it is in the cloud<br />

or on-premises. The confidentiality issue<br />

becomes a question of regulation of<br />

third-party access to a degree that satisfies<br />

practitioners’ obligations under the<br />

Australian Solicitor Conduct Rules. 2<br />

Data security is self-explanatory<br />

and has long been a concern of those<br />

looking to migrate to the cloud. As will<br />

be demonstrated, data security is also a<br />

significant issue with on-premises systems.<br />

Data resilience refers to several aspects.<br />

The most obvious being availability of<br />

data (ie: how often does a service crash).<br />

Less obvious are issues around incident<br />

management and data portability, data<br />

portability being the ability to extract data<br />

out of a cloud service if desired.<br />

Analysis<br />

The aim of my analysis is to apply<br />

the abstract concepts in the Guidelines<br />

to the practical context of cloud services<br />

commonly used by legal practitioners.<br />

To that end, I have decided to analyse<br />

the Guidelines against a set of popular<br />

cloud services and also against an onpremises<br />

context. The could services<br />

to be analysed are:<br />

• Dropbox (the consumer version); 3<br />

• Dropbox Business; 4<br />

• Google Workspace; 5<br />

• Microsoft 365; 6<br />

• LEAP; 7 and<br />

• Actionstep. 8<br />

It is worth stating that there are many<br />

other cloud services, large and small,<br />

that are available to legal practitioners.<br />

My intention is to focus on the more<br />

prominent services that many practitioners<br />

consider adopting or have already adopted.<br />

It is also worth stating that this analysis is<br />

not a substitute for performing your own<br />

due diligence!<br />

GOVERNANCE<br />

Two main points in the Cloud<br />

Computing Guidelines relate to governance<br />

– data sovereignty and jurisdictional issues.<br />

Let’s deal with data sovereignty first.<br />

Data Sovereignty<br />

As discussed above, data sovereignty<br />

relates to the location of data. The location<br />

of data is important as different countries<br />

prescribe different legal protections to data<br />

stored in them. Protections vary widely from<br />

country to country. Also, sovereign data<br />

protection may only extend to the citizens<br />

of a country. For example, data stored in the<br />

US may not be subject to the constitutional<br />

protections afforded to US citizens.<br />

Cloud services may store data across<br />

many countries. As cloud services usually<br />

store multiple copies of customer data (for<br />

resilience), it’s possible that information<br />

stored with a cloud service could fall under<br />

multiple widely-varying data legislation.<br />

Google, for example, stores its Google<br />

Workspace data in 18 different countries<br />

across the world, from the USA to Finland<br />

to Indonesia. 9