You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

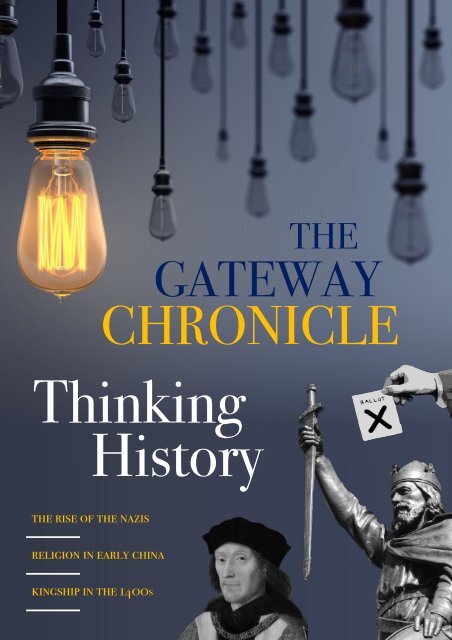

CHRONICLE<br />

Thinking<br />

History<br />

THE<br />

GATEWAY<br />

the rise of the nazis<br />

religion in early china<br />

kingship in the 1400s

“there is one thing stronger than all the<br />

armies in the world, and that is an idea<br />

whose time has come”<br />

Victor Hugo

Contents<br />

A word from the editors… 02<br />

Political ideologies 03<br />

Mare Nostrum – <strong>The</strong> rise of Fascism in Italy 04<br />

Lebensraum – <strong>The</strong> Nazis’ plan for the East and 08<br />

the largest war crime in history<br />

How was Hitler able to promote Nazism in 12<br />

1930s Germany?<br />

How was Nazi ideology reflected in their 15<br />

architecture?<br />

Labor Zionism and the creation of a state 17<br />

Individuals 21<br />

Was Henry VII really the king who created a 22<br />

new style of kingship?<br />

Gauchito Gil: <strong>The</strong> cowboy saint of Argentina 24<br />

Marlene Dietrich: Re-defining modern German 25<br />

culture and sexual liberalism in the 20 th century<br />

<strong>The</strong> music of Shostakovich 28<br />

Religion 31<br />

Establishing and developing religion in China 32<br />

<strong>The</strong> infancy of Christian England 37<br />

How did the Islamic Golden Age help develop 43<br />

modern day science?<br />

Putney Debates – October 1647 47<br />

<strong>The</strong> origins of laïcité in the French Revolution 50<br />

Senior Editors<br />

Georgie<br />

Alex<br />

Design<br />

Alex<br />

Illustrations<br />

Gracie<br />

With thanks to<br />

Mrs. Gregory<br />

Power 55<br />

<strong>The</strong> Rule of Law and Democracy 56<br />

<strong>The</strong> concept of kingship in the 1400s 60<br />

Pravda vítězí (‘truth prevails’) 64<br />

Mathematics and Economics 66<br />

<strong>The</strong> history of numbers and their development 67<br />

into modern mathematics<br />

<strong>The</strong> history of Universal Basic Income 69<br />

How laissez-faire was Britain in the late 18 th 72<br />

and early 19 th century<br />

Coronavirus – ‘the science of uncertainty?’ 74

A word from the<br />

editors…<br />

Throughout history, beliefs and ideas<br />

have varied significantly: from the early<br />

Caveman reverence for nature and fire,<br />

to the prevalent political ideologies of the<br />

modern day. Beliefs and ideas have<br />

shaped the way societies and civilisations<br />

have defined themselves, enabling<br />

people to seek unity and refuge during<br />

times of conflict and uncertainty, as well<br />

as to build community. At the same time,<br />

wars have often been fought and<br />

violence perpetrated in the name of<br />

ideology and faith, whether that be<br />

political, scientific or religious. Through<br />

this year’s chronicle title ‘Thinking<br />

History’, we hope to capture the power<br />

of ideas throughout history and the way<br />

they shaped the world today.<br />

Our magazine has been divided into five<br />

sections based on themes: Political<br />

Ideologies, Individuals, Religion, Power,<br />

and Maths and Economics, within which<br />

the articles are ordered chronologically.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se themes reflect the wide-ranging<br />

articles we received, which cover beliefs<br />

from 5000 BCE to modern day. Through<br />

this diversity of articles, we have covered<br />

a significant variety of ideas and beliefs<br />

from across the world, and we truly<br />

believe there is something for everyone –<br />

with topics ranging from the history of<br />

numbers and their integration into<br />

modern mathematics, to an exploration<br />

of religion in early China. Fittingly, there<br />

is also an article exploring the history of<br />

pandemics. It was also important to us<br />

that this year’s articles were reflective of<br />

the school community as a whole, and we<br />

encouraged wider participation from<br />

students lower down the school as well as<br />

teaching staff.<br />

As well as those who wrote articles for the<br />

<strong>Chronicle</strong> this year, we would also like to<br />

thank a few people for their invaluable hard<br />

work. Firstly, building on his experience at<br />

previous school publications, Upper Sixth<br />

student Alex Jennings has helped immensely<br />

with the creative design and layout of the<br />

<strong>Chronicle</strong>, as well as contributing an article.<br />

Alex designed the front cover and general<br />

layout of the articles and helped greatly with<br />

the formatting of the magazine. Secondly, we<br />

would like to thank Gracie Thornham,<br />

another Upper Sixth student, who very<br />

kindly produced some amazing artwork for<br />

the introduction pages to each theme.<br />

Finally, a big thank you goes to the History<br />

department and Mrs Gregory especially, to<br />

whom we can attribute the wide-ranging<br />

participation, through her encouragement<br />

and support both in the sixth form and lower<br />

down the school.<br />

Unfortunately, for reasons beyond our<br />

control, this edition of the <strong>Gateway</strong><br />

<strong>Chronicle</strong> will remain a virtual one for now,<br />

which we feel is a shame for all of those who<br />

worked so hard towards it, but given the<br />

current situation, it was the safest and only<br />

option. We hope that you are all staying safe<br />

and healthy during this time and, despite<br />

current events, you are able to enjoy reading<br />

the contributions and learning more about<br />

areas of history which you may not have<br />

thought to explore before.<br />

Georgie and Alex<br />

Senior Editors

4<br />

Political Ideologies<br />

Mare Nostrum – <strong>The</strong> Rise of<br />

Fascism in Italy<br />

T<br />

he March on Rome, ending on 29 th<br />

October 1922, signified the final<br />

blow to Italian democracy in the<br />

1920s. It replaced a parliamentary<br />

It is important to explain the main reasons<br />

why Fascism was able to take over and the<br />

context of the final March on Rome. During<br />

the<br />

“…the final blow to Italian<br />

democracy”<br />

early 1920s,<br />

both society<br />

and the<br />

economy<br />

were facing<br />

several deep underlying problems. Politically,<br />

problems had arisen because Parliament<br />

had been struck with three decades<br />

of weak majorities between the liberal parties.<br />

This coalition was finally broken in<br />

the 1919 election which<br />

saw the Socialist Party<br />

win 32 percent of the<br />

vote, mainly due to the<br />

newly introduced proportional<br />

voting system<br />

and the economic hardship<br />

post World War<br />

One.<br />

democracy with a fascist regime,<br />

led by Benito Mussolini and his<br />

National Fascist Party. <strong>The</strong>y retained<br />

their iron grip upon Italy<br />

for 21 years until 1943, following a<br />

plot to topple Mussolini’s leadership as a<br />

result of failures in World War Two. <strong>The</strong><br />

end of Fascist control also seems to have<br />

led to the end of the constitutional monarchy<br />

in Italy, following the result of a refer-<br />

Benito Mussolini<br />

endum on its abolition in 1946.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se events therefore brought<br />

upon a new chapter in Italy’s history.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rising popularity of<br />

socialism presented an intimidating<br />

force to the<br />

upper and business classes,<br />

who, in reaction,<br />

were either more sympathetic<br />

or lent their support<br />

to Mussolini. With<br />

the support of these<br />

groups, Mussolini was<br />

viewed as less revolutionary<br />

and instead a political<br />

leader that could protect<br />

the status quo. This was<br />

particularly important because<br />

it allowed the Fascists to solidify positions<br />

of power within the government,<br />

while also allowing them to operate without<br />

as much accountability for their actions.

5<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was also widespread economic and<br />

social discontent from the events of the Biennio<br />

Rosso (two red years), a period of<br />

unemployment and political instability.<br />

Following World war One, the number of<br />

unemployed had risen to 2 million, while<br />

many factories shut down for lack of government<br />

wartime contracts. This led to<br />

widespread strike action from trade unions,<br />

with 1,881 in 1920 alone and, following<br />

a rejection of their demands, they occupied<br />

factories which brought<br />

the possibility of revolution<br />

even<br />

closer. Fortunately<br />

for the<br />

other parties,<br />

the Socialists<br />

decided not to<br />

call a revolution<br />

due to their voting<br />

base of<br />

trade union<br />

members being<br />

relatively reformist<br />

rather<br />

than revolutionary.<br />

Meanwhile,<br />

the weak coalition<br />

governments<br />

were unable<br />

to supress<br />

any union activity,<br />

only urging<br />

businesses to offer<br />

concessions<br />

and, therefore,<br />

soon lost the<br />

confidence of<br />

the middle class.<br />

Within this period of economic and political<br />

chaos, an opportunity for militaristic,<br />

nationalist movements was presented.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se movements mainly consisted of the<br />

soldiers returning from World War One,<br />

students and ex-syndicalists (a labour<br />

movement that promoted unionism).<br />

<strong>The</strong>se movements expressed themselves<br />

usually in the form of violent agitation<br />

and major clashes with other political<br />

groups, predominantly workers and police<br />

at first but then socialists and communists.<br />

In April 1919, the offices of<br />

‘L’Avanti!’, a socialist daily newspaper,<br />

were burned down by fascist agitators. A<br />

continuing string of violent attacks coming<br />

from socialists, communists and fascists<br />

lasted throughout the inter-war<br />

years. However, of these, attacks by the<br />

fascist ‘Squadristi’ (better known as the<br />

Black Shirts due to the black uniforms<br />

they wore) are the most wellknown.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y were<br />

soon systematically<br />

destroying<br />

any opposition<br />

by using intimidation,<br />

assassination<br />

and<br />

strikebreaking<br />

across Italy, and<br />

even overseas in<br />

the Italian<br />

owned colony<br />

of Libya. Compared<br />

to other<br />

political factions<br />

at the time, the<br />

Squadristi were<br />

well organised,<br />

imitating the<br />

structure of the<br />

Roman military<br />

and, as a result,<br />

they were able<br />

to gain lots of<br />

members - an<br />

estimated<br />

Italian National Fascist<br />

Party logo<br />

200,000 by the<br />

time of the<br />

March on Rome.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y consolidated<br />

power in many regions by installing<br />

Squadristi squad leaders as local bosses.<br />

However, the control of the fascists in<br />

these areas was often welcomed by the<br />

middle class and landowners that wished<br />

to see a return to stability rather than the<br />

numerous strikes and civil unrest they<br />

had seen previously. As a result of this<br />

growing influence, the new ‘National

6<br />

Fascist Party’ was able to win 35 deputies<br />

(the equivalent of members of Parliament)<br />

as part of a government bloc of 275 deputies<br />

within the Parliament in the May 1921<br />

elections. This represented a large majority<br />

in the Italian Parliament with 275 out<br />

of the total 535 seats being representative<br />

of a broad coalition of nationalist and conservative<br />

outlooks. Additionally, this allowed<br />

them to hold political legitimacy rather<br />

than just being a radical group with<br />

Mussolini saw the situation unfolding before<br />

him and, therefore, began to draw up<br />

future plans before the opportunity was<br />

lost - plans for the March on Rome. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

were finalised in mid-October 1922 and<br />

envisaged public buildings being occupied<br />

in major cities, Squadristi being assembled<br />

in central Italy, an ultimatum to<br />

the government to make Mussolini the<br />

Prime Minister and finally the march into<br />

Rome itself. All these measures were<br />

Benito Mussolini<br />

power and signalled a general<br />

during the March on<br />

Rome<br />

movement from a fringe political<br />

group to an established party with<br />

the policy decisions and government sympathy<br />

it provided.<br />

made to make sure that the government<br />

was unable to respond in time, as all communications<br />

were crippled, while also<br />

providing a peaceful alternative to civil<br />

war by handing power to the Fascists. On<br />

the actual date, 27 th October, only 16,000<br />

Squadristi turned out to assembly points

7<br />

Fascist Italy<br />

around Rome with the majority not having<br />

any weapons or food- which would<br />

have required a minimal force to crush.<br />

Despite their relative weakness, due to an<br />

overestimation of their strength by the<br />

government and the speed<br />

of their assembly, no physical<br />

efforts were made to<br />

quell them. A state of siege<br />

was declared on the 28 th<br />

but was later revoked and<br />

the Prime Minister, Luigi<br />

Facta, resigned. King Victor<br />

Emmanuel then asked Mussolini to<br />

form a new government and allowed the<br />

Squadristi to conduct a victory parade in<br />

Rome. On 31 st of October, 50,000 marched<br />

through Rome brandishing an array of<br />

weapons for intimidation, while the local<br />

National Fascist Party had seized power<br />

with seemingly no physical resistance.<br />

All that Mussolini now needed to stay in<br />

control was consolidating his power. He<br />

immediately saw democracy as an obstacle<br />

to making Italy into a fascist state, only<br />

having the power of the previously incumbent<br />

Prime Ministers available to him<br />

- many of which had been unable to<br />

solve Italy’s problems as they faced large<br />

opposition. His first action to remove this<br />

problem was by passing the Acerbo Law.<br />

This changed the electoral system so that<br />

if a party gained over 25 percent of the<br />

vote then they<br />

would receive two<br />

thirds of the seats in<br />

the parliament- a<br />

system that vastly<br />

benefited the National<br />

Fascist Party.<br />

Unsurprisingly, in<br />

the following 1924 election, the National<br />

Fascist Party won 355 out of 535 seats<br />

which effectively gave Mussolini completely<br />

unchecked power. However, despite<br />

this control of the Parliament, Mussolini<br />

instead turned to the Grand Council<br />

of Fascism which he created in 1922 for<br />

governance of the country. <strong>The</strong> Council<br />

initially acted as a body for patronage<br />

within the Party (choosing the deputies<br />

for the Parliament and<br />

other local party members)<br />

but, by that time, it had effectively<br />

replaced the Parliament<br />

as the main legislative<br />

body and served to decide<br />

most other major functions<br />

of government. By<br />

1926, all rival political parties<br />

and opposition newspapers<br />

were banned, in<br />

1927 the OVRA secret police<br />

force arrested most political<br />

opponents and finally<br />

by 1928 the Grand<br />

Council of Fascism was<br />

consulted on all constitutional<br />

issues. Italy was now<br />

under the complete control<br />

of Mussolini, who appointed<br />

whoever he<br />

wanted to whatever positions,<br />

to implement his decisions<br />

on the economy and foreign policy,<br />

effectively making him dictator.<br />

“By 1926, all rival political<br />

parties and opposition<br />

newspapers were banned”<br />

Sam, L6LAB

8<br />

Political Ideologies<br />

Lebensraum: <strong>The</strong> Nazis’ plan for the<br />

East and the largest war crime in history<br />

L<br />

ebensraum as a concept has existed<br />

in Germany since Friederich<br />

Ratzel first wrote about it in 1901.<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea grew to mean expansion of German<br />

territory to accommodate Germany’s<br />

growing population For Germany, this direction<br />

was often east, towards the vast<br />

lands of Eastern Europe and Russia. In the<br />

20 th century, twice Germany has driven<br />

eastwards under an autocratic government<br />

to conquer land in eastern Europe.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first was during the World War One,<br />

where the German Empire in<br />

tandem<br />

with<br />

Austria-<br />

Hungary<br />

bludgeoned the<br />

Russian Empire into civil<br />

war, setting up puppet regimes<br />

with plans to colonies areas of Poland,<br />

the Baltic States and Ukraine<br />

under the abortive Septemberprogramm<br />

which involved the ethnic<br />

cleansing of Jews and Poles<br />

from areas of annexed Poland.<br />

However, it is the second attempt<br />

which is the focus of today’s<br />

piece; Nazi Germany’s Generalplan<br />

Ost (Master Plan for the East).<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea of Lebensraum in Nazi ideology<br />

was popularized by the movement’s eventual<br />

leader, a certain Adolf Hitler. In the<br />

titular Mein Kampf, he states that ‘the German<br />

people must be assured the territorial<br />

area which is necessary for it to exist’ and<br />

‘the German frontiers are an outcome of<br />

chance and only temporary frontiers’. This<br />

outlines the framework of his idea, primarily<br />

the expansion of Germany into<br />

Eastern Europe at the expense of other nations,<br />

to create more space for the burgeoning<br />

German population (despite the<br />

fact that the German birth rate had been<br />

declining since the 1880s). Furthermore,<br />

they needed to secure resources, such as<br />

farmland, so that Germany would never<br />

be hit with the kind of mass starvation<br />

that happened to Germany in World War<br />

One, due to the Entente blockade, and raw<br />

materials to power German industry and<br />

further the principle of Autarky (German<br />

economic independence and self-reliance).<br />

This was also partially based on his hatred<br />

of both Jews and Soviet Communism,<br />

which he saw as linked through<br />

the<br />

conspiracy<br />

theory<br />

that Jews<br />

organised the<br />

1917 Russian Revolution and<br />

were using communism as a tool<br />

for world domination.<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea was already there<br />

within the Nazi party but,<br />

upon the commencement of<br />

World War Two, the Nazis<br />

now planned to make this idea<br />

a reality, with all the horror that<br />

entailed. For this, the Nazis gradually<br />

began development on Generalplan<br />

Ost, their plan for genocide, ethnic<br />

cleansing and colonisation in Central and<br />

Eastern Europe, the extent of which was<br />

known only to the top echelon of the Nazi<br />

party. <strong>The</strong> plan was divided into 2 phases,<br />

Kliene Planung and Gross Planung. <strong>The</strong> former<br />

dictated German colonial policy during<br />

the war, whilst the latter was due to be<br />

implemented over 30 years to cement German<br />

control. <strong>The</strong> Kliene Planung was partially<br />

completed during the war, consisting<br />

of the killing of any leaders, whether<br />

political, military or cultural, in the Eastern<br />

European states as well as Jews,

9<br />

Gypsies and the mentally ill. <strong>The</strong>re were 4<br />

drafts of the plan, with the first being in<br />

1940 and the last in 1942. This was prefaced<br />

by the invasion of Poland, where 7<br />

SS Einsatzgruppe, special task forces<br />

formed by Reinhard ‘Young Evil God of<br />

Death’ Heydrich to carry out mass murder<br />

of anyone not deemed acceptable by the<br />

Nazi regime, followed the regular army,<br />

who's goal was to eliminate "all anti-German<br />

elements in hostile country behind<br />

the troops in combat", which is a fancy<br />

way to say killing all Polish figures of political<br />

or military importance and Jews.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Germans attempted to crush Polish<br />

culture through the execution of 60000<br />

Polish ex-government officials, reserve<br />

army officers, landowners, clergy and<br />

members of the intelligentsia were killed<br />

in 10 regional actions, as characterised by<br />

Hitler’s order ’Whatever we find in the<br />

shape of an upper class in Poland will be<br />

liquidated’. Whilst eliminating many cultural<br />

and political influencers in Poland<br />

with the goal of destroying the Polish<br />

sense of identity, they also took out many<br />

people who could lead an uprising. This<br />

process was continued by Operation AB-<br />

Aktion, where 30,000 more Poles were arrested<br />

from major cities across occupied<br />

Poland, interrogated in prisons then transferred<br />

to concentration camps in order to<br />

keep the growing Polish resistance scattered<br />

so there would be no disturbances<br />

during the upcoming invasion of France.<br />

Thousands of intellectuals were massacred<br />

in mass executions, for example with<br />

the Palmiry massacre, in 1946 investigators<br />

from the Polish Red Cross found the<br />

bodies of 2180 men and women in 24 mass<br />

graves, all executed by gunfire for crimes<br />

such as being a Polish artist, an athlete or<br />

even living in the same a<br />

partment block as a resistance member.<br />

Hundreds of thousands had already died<br />

due to the deliberate actions of the German<br />

authorities in Poland, but that was<br />

barely a drop of blood in a mass grave<br />

compared to what was coming next. Operation<br />

Barbarossa, the Nazi invasion of the<br />

Soviet Union. Millions of those the Nazi’s<br />

viewed as being from inferior races were<br />

brought under the control of a state with<br />

the will and the means to commit one of<br />

the largest atrocities in history. <strong>The</strong><br />

Einsatzgruppen were divided into 4 sections,<br />

marked A, B, C and D, and spread<br />

across the Eastern front to follow behind<br />

the troops executing mid and high level<br />

Communist Party officials, dedicated<br />

Communists, the mentally ill, members of<br />

the Roma people and all Jews, working in<br />

tandem with the regular German army to<br />

commit<br />

massacres<br />

on multiple<br />

occasions.<br />

After November<br />

1941, it was<br />

decided<br />

that there<br />

would be a<br />

transition<br />

to using<br />

gassing targeted<br />

people<br />

after the<br />

leader of<br />

the SS<br />

Heinrich<br />

Himmler<br />

visited a<br />

mass execution<br />

of 100<br />

Jews near<br />

Minsk, being<br />

thoroughly<br />

nauseated by the experience,<br />

it was deemed that<br />

mass shootings were taking too much of a<br />

mental and physical toll on the Einzatsgruppen<br />

themselves. Overall, estimates<br />

put the death toll from the<br />

Einsatzgruppen and related agencies between<br />

1.5 and 2 million with millions<br />

more being sent to labour or death camps.<br />

In the relatively short span of 6 years, the<br />

Nazis perpetrated 3 out of the 5 most<br />

deadly genocides in history if taken in<br />

‘Our Lebensraum even lies<br />

here!’ – A Nazi propaganda<br />

poster from WW2

10<br />

isolation. Firstly, the Holocaust. <strong>The</strong> Jews<br />

were the focus of their racial hatred and as<br />

a result were the primary focus of the<br />

Nazi's ethnic cleansing. Jews were deported<br />

from across Europe to German<br />

concentration camps, initially designed to<br />

function as work camps, where the death<br />

rates were high but they were not designed<br />

for mass extermination at first. After<br />

the Wanasee Conference on 20 January<br />

1942, where the ‘Final Solution to the Jewish<br />

Question’ was decided. All Jews in Europe<br />

would be killed, worked to death or<br />

deported to undecided locations in the<br />

East. Under these orders, 6,000,000 Jews,<br />

or 2/3 of Europe’s Jewish population,<br />

died through a combination of shootings,<br />

gassings, starvation and being worked literally<br />

to death. Secondly, the rest of Generalplan<br />

Ost where, even in its incomplete<br />

phase, with the total death toll estimated<br />

to be between<br />

4.5 million and<br />

nearly 14 million,<br />

using similar<br />

methods to<br />

the Holocaust,<br />

such as seizing<br />

all farmland in<br />

the Ukraine and<br />

sending all produce back to Germany<br />

combined with German soldiers being ordered<br />

to ‘live off the land’ to avoid having<br />

to manage the chaotic and expensive logistics<br />

of feeding the troops during the<br />

largest ground invasion ever, causing<br />

mass starvation among the occupied areas.<br />

<strong>The</strong> third was the Nazi occupation of<br />

Poland, in which 13% of Poland’s pre-war<br />

population were killed in an effort to Germanise<br />

the area, to combat the resistance<br />

through methods such as reprisal killings,<br />

more forced labour and the infamous<br />

Warsaw uprising.<br />

From the ruins of the Soviet Union, Germany<br />

planned to set up 4 puppet states<br />

would be carved out. Reichskomissarat(RK)<br />

Ostland, consisting of the Baltic<br />

States, part of Belarus and stretching to<br />

Leningrad, RK Ukraine, RK Kaukasien,<br />

Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and most of<br />

the Russian Caucasus, and RK Moskowien,<br />

all the land east of Ostland and<br />

Ukraine up to an arbitrary line between<br />

Archangelsk and Astrakan (the A-A Line),<br />

with thisthe finish line for Barbarossa. In<br />

reality, only Ostland and Ukraine were<br />

ever set up as Germany’s invasion was<br />

turned around before these other areas<br />

could be brought fully under their control.<br />

Next, the areas acquired in the name of<br />

Lebensraum had to undergo 'Germanisation’<br />

where the culture and often the local<br />

people themselves of a country were destroyed<br />

and replaced with those culturally<br />

or ethnically German. Certain percentages<br />

of the population of the local population<br />

were selected for Germanisation as they<br />

apparently were racially similar enough to<br />

Germans (Nazi racial policy was based on<br />

science that was very shaky at best and extremely<br />

harmful<br />

pseudoscience<br />

“In the relatively short span of 6 years,<br />

the Nazis perpetrated 3 out of the 5<br />

most deadly genocides in history”<br />

at worst). <strong>The</strong>se<br />

figures were<br />

seemingly<br />

picked at random<br />

with 50%<br />

of Czechs, 35%<br />

of Ukrainians<br />

and 10% of Poles possessed ‘Germanic<br />

blood’ and those not selected were to be<br />

killed, sent to forced labour camps or deported<br />

to Siberia. Even children were not<br />

spared. An estimated 50,000 to 200,000<br />

Polish children who were deemed to have<br />

German traits were taken from their parents<br />

to be Germanised and re-introduced<br />

into German society. Only 10-15% ever<br />

made it back to their parents and thousands<br />

ended up in concentration camps.<br />

During the war, 350,000 Baltic Germans<br />

and 1.7 million Poles were the subject of<br />

Germanisation, plus 400,000 Germans<br />

were sent from Germany to help colonise<br />

the new conquests. As the Nazis pushed<br />

further and further east, Germanisation efforts<br />

became confused, with some in<br />

Ukraine being torn between the German<br />

rule of needing 3 German grandparents to<br />

be classed as German whilst some saw no

11<br />

reason to kill people if they acted German<br />

and showed no ’racial concerns’. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

were also further disagreements where<br />

the Reich decided a person was Jewish if<br />

they had 3 Jewish grandparents, but the<br />

Einsatzgruppen decided it was if you had<br />

one Jewish grandparent, weather you<br />

practiced the religion or not, further showing<br />

the inconsistencies of the pseudoscience<br />

and the unlucky dip that was Nazi<br />

racial policy.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kleine Planung resulted in some of the<br />

largest man-made losses of life in history,<br />

and this is just the ’small’ half of the plan<br />

carried out over 6 years. <strong>The</strong> Gross Planung<br />

was to be even more horrific,<br />

involving the removal of 45 million<br />

people from Central and Eastern<br />

Europe via being sent to the death<br />

camps, deliberate starvation due to<br />

seizure of food supplies or deportation<br />

to Siberia. This would involve<br />

50-60% of Russians exterminated<br />

with 15% being driven to Siberia,<br />

nearly 50% of Estonians, 50%<br />

of Latvians, 50% of Czechs, 65% of<br />

Ukrainians, 75% of Belarussians,<br />

80-85% of Poles, 85% of Lithuanians<br />

and 100% of Latgalians. Deportation<br />

to Siberia is simply a euphamism<br />

for mass murder as, with<br />

very little infrastructure to accommodate<br />

to new arrivals, they<br />

would freeze or starve to death in<br />

the wilderness. Even the most advanced<br />

countries today would struggle heavily to<br />

properly provide for an influx of millions<br />

of people, let alone the less developed areas<br />

of what was to be a military crushed<br />

USSR. <strong>The</strong> regions would then be repopulated<br />

by 8-10 million German settlers and<br />

all the recently Germanised peoples over<br />

the next 2-3 decades in order to fully<br />

transform the Slavic lands into German<br />

ones. As there were not enough Germans<br />

to properly populate the new conquests,<br />

people judged to be racially between Germans<br />

and Russians called Mittleschicht (e.g<br />

Latvians and Czechs) were also to be settled<br />

there. Near the end of the war, all<br />

copies of Generalplan Ost were destroyed<br />

as the horrific plans detailed within which<br />

would almost certainly warrant the death<br />

penalty for anyone involved in its execution,<br />

but we have been able to reconstruct<br />

the main points of it through various documents<br />

referring to it or supplementing it<br />

as well as the testimonies of SS officers<br />

during the Nuremburg trials.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Second World War was a long time<br />

ago and to many of us and numbers on a<br />

page are hard to comprehend. <strong>The</strong> total<br />

death toll of Lebensraum is hard to accurately<br />

place, but civilian casualties sat in<br />

the tens of millions due to this one idea,<br />

‘Danzig greets its leader!’ –<br />

civilians who had parents, <strong>The</strong> Nazi invasion of Poland,<br />

children or siblings as entire<br />

September 1939<br />

towns and villages were<br />

mercilessly wiped out. <strong>The</strong> idea of Lebensraum<br />

was a horrific one and it is a<br />

dark stain on humanity that it proceeded<br />

as far as it did without seeing severe ethical<br />

objections about from the German<br />

army or high command. We can only<br />

thank God that the Allies managed to defeat<br />

the forces of evil, resulting in unprecedented<br />

growth in the latter half of the 20 th<br />

century, instead of the unspeakable atrocities<br />

that would have come about if Generalplan<br />

Ost was seen to its conclusion.<br />

Henry, L6JRW

12 Political Ideologies<br />

How was Hitler able to promote<br />

Nazism in 1930s<br />

Germany?<br />

B<br />

y 1933, Germany had already suffered<br />

a depression and its streets<br />

were plagued with hyperinflation<br />

and poverty, so they were in desperate<br />

need of a new ideology to steer them to<br />

success. As Nazism spread through Europe<br />

like an infection in the 1930s, it<br />

seemed this would result in a reinvigorated<br />

Germany, a far cry away from the<br />

one who had been humiliated at Versailles.<br />

However, the challenge of maintaining<br />

and enforcing this new regime<br />

proved to be the test of Nazism; how<br />

much did German citizens want this new<br />

ideology and what methods did Hitler<br />

employ to ensure they wanted it?<br />

Dr Joseph Goebbels and the mighty propaganda<br />

machine were pivotal to the survival<br />

of Nazism. He had the power to not<br />

only censor any media criticising the<br />

Reich but also the power to control mainstream<br />

media. <strong>The</strong> organization of the Nuremberg<br />

rallies, pro-Nazi radio broadcasts,<br />

Nazi cinema and newspapers all<br />

helped to<br />

ensure Hitler<br />

stayed<br />

in power<br />

and continually<br />

promoted<br />

Nazism.<br />

Books<br />

and works<br />

of art were restricted to only ones promoting<br />

the Nazi message and those deemed<br />

unacceptable were burnt. Hitler did this to<br />

attempt to censor all media and appeal to<br />

the German multitudes but also as a public<br />

demonstration of the rejection of alternative<br />

ideas.<br />

Goebbels<br />

was able to<br />

marry his<br />

fascination<br />

with new<br />

technology<br />

to his<br />

power of<br />

media censorship.<br />

In<br />

this way,<br />

he was able<br />

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s<br />

to tap into the mind of every<br />

propaganda minister<br />

German as his media was so<br />

mainstream and cheap. Consequently,<br />

everyone was exposed to propaganda no<br />

matter their social status or education.<br />

Germany was in a depression, but Goebbels<br />

combated this by putting speakers in<br />

bars and creating cheap radios. It was on<br />

these radios that Hitler’s speeches were<br />

repeated – guaranteeing that his ideas<br />

were heard by all.<br />

Posters aimed at the poorly educated<br />

had simplistic<br />

bright<br />

“Goebbels had the power to not only censor<br />

any media criticising the Reich but also<br />

the power to control mainstream media”<br />

pictures to attract<br />

them. <strong>The</strong><br />

content and design<br />

typically<br />

featured povertystricken<br />

Germans<br />

and exposed Communists and Jews<br />

as the cause of this problem. This visual<br />

propaganda meant that it appealed to<br />

those who couldn’t afford to visit an art<br />

gallery or visit the cinema but at the same<br />

time it attracted Germans everywhere<br />

with its dramatic slogans and shocking

13<br />

pictures. This, again, promoted the idea of<br />

the Fuhrer and gave the average German<br />

during the depression hope that Nazism<br />

could recover Germany’s former<br />

glory.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Berlin Olympics in 1936 only further<br />

served to exaggerate the power of the Nazis<br />

on the<br />

world<br />

stage. With<br />

Germany<br />

topping the<br />

medals table<br />

in the<br />

state-of-theart<br />

arena,<br />

doubters of<br />

the regime<br />

both inside<br />

and outside<br />

of Germany<br />

were silenced.<br />

As<br />

well as<br />

boosting<br />

national<br />

pride, the<br />

Olympics<br />

further<br />

served as a<br />

reminder of<br />

Aryan superiority.<br />

Hitler knew the key to unlocking the full<br />

potential of Germany was the support of<br />

the German masses. His promises of employment<br />

and German glory won over<br />

some, but others<br />

needed a stick<br />

to complement<br />

this carrot. This<br />

came in the<br />

form of violent<br />

law enforcers.<br />

<strong>The</strong> SS were<br />

formed from the<br />

ashes of the SA and were trained meticulously<br />

by Heinrich Himmler. <strong>The</strong>ir sole<br />

aim was to destroy any opposition to Nazism<br />

and strengthen the stranglehold that<br />

the Nazis had on Germany. <strong>The</strong>y ruled<br />

with an iron fist; they ensured nobody<br />

stepped out line with the threat of concentration<br />

camps at their disposal. Unsurprisingly,<br />

the SS were all Aryans with zealous<br />

devotion to Hitler which enabled them to<br />

commit the most ruthless acts of torture<br />

and violence to eliminate opposition. At<br />

the same time, the SS became a<br />

form of promotion for Nazism as<br />

Himmler had created an idealistic, elitist<br />

order that was unparalleled since the ages<br />

of knights.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> aim of the SS was to destroy any<br />

opposition to Nazism and strengthen<br />

the stranglehold that the Nazis had on<br />

Germany”<br />

Nazism was reinforced<br />

by<br />

newly implemented<br />

social<br />

policies. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

were introduced<br />

gradually so as<br />

not to shock the civilians. Nazism’s<br />

shameless promotion of Aryan superiority<br />

led to the persecution of minorities, in<br />

particular, Jews. As well as holding them<br />

Hitler attending the<br />

1936 Berlin Olympics

14<br />

at fault for losing the First World War,<br />

Hitler believed that their race was inferior<br />

that of the Aryan. To accept the principles<br />

of Nazism, the German citizens had to<br />

truly believe that they were the Herrenvolk<br />

(master race).<br />

This meant Hitler put in place restrictions<br />

on German Jews to reinforce this idea. By<br />

banning them from owning businesses, he<br />

reinforced the idea that Jews profited<br />

from the failure of<br />

others. By implementing<br />

this ban,<br />

he was able to<br />

convince and assure<br />

faithful Nazi<br />

supporters of the<br />

Jew’s evil nature.<br />

He stopped Jews<br />

becoming German<br />

citizens, lawyers,<br />

doctors or journalists.<br />

He also<br />

barred them from<br />

schools and social<br />

and sports clubs,<br />

stopped mixed racial<br />

marriages and<br />

relationships. In<br />

addition, Jewish<br />

shops and people<br />

were marked with<br />

a Star of David.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se policies<br />

led to ordinary<br />

German civilians<br />

having less everyday<br />

contact with<br />

Jews, cementing<br />

the ideologies of Nazism. <strong>The</strong>se policies<br />

were, albeit in a less extreme manner, mirrored<br />

regarding other minority groups<br />

like Communists, African Americans, homosexuals,<br />

and gypsies. In particular, the<br />

campaign against Communism made it<br />

easier for Germans to embrace Nazism.<br />

Great emphasis was placed on the education<br />

of the young with the Hitler Youth<br />

and German League of Maidens being<br />

created. <strong>The</strong>y were vital to ensure Hitler<br />

achieved a ‘1000-year Reich’ because, not<br />

only did they teach children arms drills,<br />

they further exaggerated a common enemy.<br />

Hitler focused on the younger generations<br />

as he knew that by isolating them<br />

from their parents, through love for the<br />

Nazis, would mean their primary loyalty<br />

would be to Hitler and not them. This led<br />

to children reporting their parents and<br />

made it easier for the Nazis to silence enemies<br />

of the state<br />

who complained<br />

within the confines<br />

of their own<br />

homes. By e<br />

ffectively brainwashing<br />

the next<br />

generation, Nazism<br />

was further<br />

forced upon the<br />

German society.<br />

A propaganda poster for the<br />

Hitler Youth<br />

In their own ways,<br />

each of the methods<br />

employed by<br />

the Nazis were<br />

able to alter the<br />

opinions of the<br />

German masses.<br />

While the fear and<br />

propaganda techniques<br />

preyed previously<br />

existing<br />

prejudice, social<br />

controls ensured<br />

compliance and alienation<br />

of anyone<br />

who didn’t fit the<br />

Nazi model. Hitler<br />

made the choice to<br />

the people black and white: you were either<br />

with the Nazis or against them. With<br />

the threat of the SS looming over them,<br />

the German citizens had very little choice<br />

but to accept the Nazi regime and with it<br />

their ideology.<br />

Arthur, 5.3

Political Ideologies<br />

15<br />

How was Nazi ideology<br />

reflected in their architecture?<br />

A<br />

fter coming to power in 1933,<br />

Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party<br />

began a radical transformation of<br />

German culture, including architecture.<br />

Indeed, architecture played a large role in<br />

Hitler’s regime, with his chief architect Albert<br />

Speer becoming one of the most important<br />

men in the Nazi government by<br />

the 1940s. <strong>The</strong> designs formulated<br />

by the Nazis very<br />

much reflected their political<br />

agenda.<br />

Firstly, Nazi architecture<br />

reflected the authoritarian<br />

and populist nature of<br />

their rule and their ideology.<br />

Hitler himself was renowned<br />

for his populist<br />

tactics, including large<br />

public addresses which<br />

sought to enthuse his followers<br />

and whip up support.<br />

As a result, his architecture<br />

often accommodated<br />

such methods of outreach. For example,<br />

a 30 square kilometre area near<br />

Nuremburg was supposed to be developed<br />

in order to host up to 500,000 guests<br />

for Nazi rallies, demonstrating how the<br />

populist elements of Nazi ideology were<br />

mirrored in their architecture. Likewise,<br />

plans for a new city called ‘Germania’ to<br />

replace Berlin included buildings such as<br />

the ‘Volkshalle’, or People’s Hall, further<br />

demonstrating the populist nature of Nazi<br />

ideology, and echoing their desire to build<br />

a utopian society with similarly named<br />

policies such as the ‘Volksgemeinschaft’.<br />

Nazi architecture also reflected the more<br />

sinister, authoritarian elements of their regime.<br />

Indeed, many of the planned buildings<br />

were designed in such a way that<br />

they highlighted the domineering nature<br />

of their rule. <strong>The</strong> aforementioned<br />

Volkshalle was planned to have a 300-metre-high<br />

dome in the style of Hitler’s favoured<br />

neo-classicism. Hitler even stated<br />

that ‘our enemies and followers must realise<br />

that these buildings strengthen our authority’,<br />

perhaps because the sheer size of<br />

his buildings would have dwarfed the individual<br />

and acted as a visible metaphor<br />

for extreme state power.<br />

Likewise, architecture was used by the<br />

Nazis as a means by which to demonstrate<br />

their supposed supremacy over rivals and<br />

those who they viewed as ‘inferior’. Supremacy<br />

played a large role Nazi propaganda<br />

– they sought to build the image of<br />

the supposedly superior Aryan race. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

truly believed that the Aryans were a<br />

‘master race’ who prevailed over all others,<br />

especially over the perceived ‘inferior<br />

races’ such as the Slavs and the Jews. Indeed,<br />

there is much evidence of their bid<br />

for Germanic superiority in their architecture.<br />

Firstly, only German materials were<br />

used in many of their most important architectural<br />

projects.<br />

<strong>The</strong> proposed<br />

‘Volkshalle’ of Berlin

16<br />

For instance, for the 1937 Paris International<br />

Exhibition of Arts and Technology,<br />

Speer designed and built a huge 65-metre<br />

tower out of only German materials. Relying<br />

solely on German materials helped<br />

them to showcase their belief in German<br />

superiority on an international stage, as it<br />

suggests that they viewed non-German<br />

materials as unworthy. Combined with<br />

the imposing nature of the tower, this<br />

demonstrated further how the Nazis<br />

wanted to pursue their all-powerful image<br />

in their architecture,<br />

almost<br />

as if it was a<br />

form of propaganda<br />

itself.<br />

More importantly,<br />

the<br />

tower was almost<br />

an exact<br />

replica of the<br />

Soviet version (for which the Nazis had<br />

acquired the blueprints), but the only major<br />

difference was the fact that the German<br />

version was much bigger, proving how<br />

the Nazis used architecture in order to devalue<br />

their rivals and to uphold their perceived<br />

superiority and authority. <strong>The</strong><br />

Olympic Stadium in Berlin was also built<br />

in an elaborate neo-classical style preferred<br />

by Hitler in order to showcase the<br />

perceived German sporting superiority.<br />

“Nazi architecture<br />

reflected the authoritarian<br />

and populist nature of<br />

their rule and ideology”<br />

Similarly, the Nazis used architecture as a<br />

means by which to promote their traditionalist<br />

ideological values. Indeed, during<br />

the Weimar Period, architecture became<br />

a progressive force for change,<br />

alongside other elements of German culture<br />

such as the performing arts and music.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Art Deco buildings which hosted<br />

such modern culture were in many ways<br />

symbolic of the changes that were going<br />

on in German society. Of course, the Nazis<br />

ideologically detested such changes. Hitler<br />

and his party were innately traditionalist,<br />

believing developments during Weimar<br />

Germany to be ‘un-German’, such as<br />

the new, financially independent role of a<br />

woman in society. <strong>The</strong>refore, they sought<br />

to reverse the changes to architecture<br />

which had been symbolic of modern Weimar<br />

society. <strong>The</strong> Nazis were especially<br />

critical of housing schemes during the<br />

Weimar Republic, which took on modernist,<br />

experimental designs, going against<br />

everything the Nazis believed in. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

much preferred the traditional Germanic<br />

housing designs; the type that one would<br />

probably expect to see in old Germanic<br />

fairy tales. Indeed, many senior Nazis had<br />

their residences built in this style, including<br />

Hermann Goering’s “Carinhall”. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

similarly wanted to build youth hostels in<br />

this style, reflecting another aspect of Nazi<br />

ideology – the belief in indoctrinating the<br />

youth. Likewise, not only did the Nazis<br />

oppose modernist and experimental design,<br />

but many also opposed the heavy industrial<br />

architecture that had come to<br />

dominate cities such as Berlin. It was no<br />

secret that Hitler didn’t like Berlin – he<br />

spent little time there after all, despite it<br />

being Germany’s capital. Rapid industrialisation<br />

was another aspect of modern German<br />

life which the Nazis opposed, since it<br />

went against the aforementioned traditionalist<br />

image that they yearned for, and<br />

as such they planned to renovate Berlin<br />

into ‘Germania’ before 1950, which would<br />

supposedly have captured the essence of<br />

the their desired view of Germany. Hitler<br />

himself drew up the basic plan, which was<br />

to include neo-classical architecture such<br />

as the Volkshalle. This renovation of Berlin<br />

thus demonstrates the Nazis’ antimodernist<br />

values.<br />

In many ways then, Nazi architecture<br />

acted as a metaphor for their regime.<br />

Huge projects such as the planned city of<br />

Germania demonstrated the sheer authority<br />

of the Nazi state, whilst also highlighting<br />

their hatred of progressive Weimar<br />

culture. Likewise, the Nazis’ opposition to<br />

modern architecture was evidence of their<br />

favour for traditionalism.<br />

Alex

Political Ideologies<br />

17<br />

Labor Zionism and the<br />

creation of a<br />

state<br />

T<br />

he first - and now second longest<br />

serving - Prime Minister of<br />

Israel was David Ben-Gurion;<br />

he declared that, “<strong>The</strong> assets of the<br />

Jewish National Home must be created<br />

exclusively through our own work.”<br />

This idea is known as Labor [sic] Zionism,<br />

but what was Labor Zionism and<br />

how powerful was this idea and the<br />

actions it brought about in bringing<br />

about a “Jewish National Home”?<br />

Before one can begin to answer that<br />

question, it is necessary to first understand<br />

what Labor Zionists actually believed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> primary focus of Labor Zionists<br />

was the creation of a Jewish State<br />

through manual labour; it was believed<br />

that only a Jewish proletariat could bring<br />

about a Jewish State. In order to bring<br />

that about, Labor Zionists relied on the<br />

emigration of diaspora Jews to Palestine.<br />

However, merely the presence of Jews<br />

was not sufficient; Labor Zionists had<br />

three goals of ‘Kibbush’ (roughly translated<br />

as ‘Conquest’): guarding land (that is agriculture)<br />

and labour (that is any non-academic<br />

work). It was believed that when<br />

Jews did all three types of work, and only<br />

then, could a solution to the question of<br />

Jewish statehood be found: whether that<br />

be political or revolutionary.<br />

Arguably, the most interesting part of this<br />

was the methods used by Labor Zionists<br />

to achieve ‘Kibbush’. In 1910, the first of<br />

many ‘kibbutzim’ was founded: D’ganya.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se kibbutzim aimed to create an environment<br />

that encouraged Jewish diaspora<br />

emigration to Palestine by facilitating<br />

<strong>The</strong> Palestine<br />

‘social salvation’ in the form of an<br />

Post, May 14, 1948<br />

agrarian, egalitarian commune and<br />

‘individual salvation’ in the form of service<br />

to a wider community. <strong>The</strong>se communities<br />

received many refugees of Russian<br />

pogroms but also radical socialist Zionist<br />

youth and, by 1939, 24,105 people<br />

were living on kibbutzim. In fact, even today<br />

many of these kibbutzim still exist (although<br />

only about 60 still exist on a communal<br />

basis as of 2010) and account for<br />

about 40% of Israel’s agricultural output.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were a variety of opinions on how<br />

this might lead to a Jewish State in Palestine:<br />

while the Marxist elements of the<br />

movement argued that an active Jewish<br />

proletariat would naturally create a revolution<br />

that would build a Jewish State,<br />

others merely argued that it facilitated<br />

Jewish economic independence in the region<br />

that would facilitate the creation of a<br />

state by purely political means.

18<br />

With that said, how did it actually contribute<br />

to the creation of the State of Israel in<br />

1948?<br />

To briefly recap, the State of Israel was declared<br />

in 1948 following the approval of<br />

the United Nations partition plan by the<br />

General Assembly which had precipitated<br />

a civil war in British Mandatory Palestine.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Partition Plan itself was created at the<br />

request of the British Government who<br />

had concluded in 1937 that its Mandate of<br />

Palestine was untenable due to the conflict<br />

between Jews and Arabs in the region and<br />

– after the Second World War – were<br />

<strong>The</strong> First Prime<br />

Minister of Israel, struggling to control Jewish revolt<br />

David Ben-Gurion over the limits on Jewish migration<br />

to Palestine (especially in the aftermath<br />

of the Holocaust).<br />

One impact of Labor Zionism was that the<br />

radical ‘kibbutznik’ represented a large<br />

group of Jews living in Palestine who<br />

were willing to fight for a state. In fact, the<br />

predecessor to the modern Israel Defence<br />

Forces, the Jewish paramilitary ‘Haganah’<br />

(literally, ‘the defence’) was linked to the<br />

Labor Zionist movement; Haganah was<br />

considered the largest armed force in the<br />

region after the British Army. <strong>The</strong>se paramilitary<br />

groups smuggled weapons into<br />

Palestine and were part of the armed revolts<br />

which proved the British Mandate<br />

untenable. <strong>The</strong>se armed rebellions ultimately<br />

forced the British out, but it is<br />

equally likely that the British would have<br />

been forced to leave anyway; there was an<br />

appetite for self-determination among the<br />

United Nations and the British especially<br />

were not desperate to keep it in their Empire.<br />

However, it is certainly true that the<br />

military wing of the Labor Zionist movement<br />

sped up the British withdrawal.<br />

Nevertheless, the partition would never<br />

have been considered without a viable alternative.<br />

For<br />

the Jewish<br />

State at least,<br />

this came<br />

from the Labor<br />

Zionists.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kibbutzim<br />

– as well as<br />

‘nomadic’<br />

groups such<br />

as G’dud<br />

HaAvodah<br />

(Labor Battalion)<br />

– created<br />

viable agriculture<br />

and<br />

manual labour<br />

forces<br />

for a future<br />

state; G’dud<br />

HaAvodah notably built roads and drained<br />

swamps in the 1920s where the British had<br />

not. Moreover, the associated labour unions<br />

(mainly Histadrut, that of David Ben<br />

Gurion) began to establish education,<br />

health care and social services for the Jewish<br />

population outside of the kibbutzim<br />

themselves. This created the very beginnings<br />

of the State: one which not only had<br />

some sort of economic output but provided<br />

for its citizens. <strong>The</strong>refore, as a result<br />

of the institutions of Labor Zionism (themselves<br />

a result of the ideology), it was<br />

possible both for the United Nations and<br />

the British government to consider a Jewish<br />

State in the region; after all, there

19<br />

already appeared to be a State at the<br />

hands of the Labor Zionists so Labor Zionism<br />

made it more difficult to refuse a formal<br />

Jewish State too. Indeed, the United<br />

Nations Special Committee on Palestine<br />

Report specifically notes that kibbutzim,<br />

“express the spirit of sacrifice and co-operation<br />

through which [agricultural success]<br />

has been achieved”.<br />

Regardless, a Jewish State would not have<br />

been considered without a Jewish population<br />

in Mandatory Palestine. This too was<br />

provided in part by the Labor Zionists. Of<br />

course, the various issues facing European<br />

Jews (social and economic) were the main<br />

‘push factors’ but the kibbutzim created a<br />

method of getting<br />

work, finding<br />

a community<br />

upon arrival and<br />

– for most immigrants<br />

during the<br />

Third Aliyah (literally<br />

‘ascent’,<br />

but a word for<br />

the waves of migration)<br />

from<br />

1919 until 1923<br />

but fewer immigrants<br />

among the<br />

later (and larger)<br />

waves of Aliyot –<br />

provided an ideological<br />

home for socialist Jews. While<br />

only a minority of Jews lived on kibbutzim,<br />

their success did create a sense among the<br />

Jewish diaspora that moving to Israel was<br />

possible; for many it grew to be necessary,<br />

but it did make the move more palatable.<br />

In 1936, the local population of Palestine<br />

began a general strike that turned into a<br />

violent rebellion; the 1937 Peel Commission<br />

found the cause of this to be the rapid<br />

demographic change. <strong>The</strong> Peel Commission<br />

also concluded that the Mandate was<br />

untenable and that partition would be<br />

necessary; according to Roza El-Elini, the<br />

Commission’s report, “proved to be the<br />

master partition plan, on which all those<br />

that followed were either based, or to<br />

which they were compared”. Furthermore,<br />

the presence of a Jewish population<br />

specifically was vital for a Jewish State to<br />

be considered; if there were no Jews in<br />

Palestine, there would have been no reason<br />

to consider creating a state for Jews in<br />

Palestine. This strongly suggests that Labor<br />

Zionism had a notable impact on the<br />

demographic change which ultimately<br />

lead to the partition of Palestine and hence<br />

the creation of the State.<br />

With that said, there were many other significant<br />

factors in the creation of the State<br />

of Israel. First among them was the collapse<br />

of the Ottoman Empire. From the<br />

beginning of the First World War, the British<br />

Government<br />

concerned itself<br />

with the fate of<br />

Ottoman Palestine.<br />

As part of<br />

that, the British<br />

Government entered<br />

into negotiations<br />

with another<br />

group of<br />

Zionists: the socalled<br />

Political<br />

Zionists, who<br />

aimed to create a<br />

Jewish State<br />

through pure diplomacy.<br />

<strong>The</strong> result<br />

of the negotiations was the Balfour<br />

Declaration of 2 November 1917, giving<br />

sympathy to the Zionist Cause. Historians<br />

have argued at great length as to why the<br />

Government did this; Lloyd-George himself<br />

claimed in his memoir it was to gain<br />

financial support from Jews and the<br />

American Government (Geoffrey Wheatcroft<br />

notes that the Balfour Declaration<br />

was almost “Wilson’s Fifteenth Point”), to<br />

prevent Zionist support for Germany, due<br />

to the negotiating of the Political Zionists<br />

and his own support for the cause. Whatever<br />

the actual reason, the declaration is of<br />

paramount importance to the Zionist<br />

cause. <strong>The</strong> declaration was later endorsed<br />

by the United States and gave hope to

20<br />

Zionists both in Palestine and the Jewish<br />

diaspora. Ultimately, the Balfour Declaration<br />

served as the basis for all future efforts,<br />

and the basis (if not motivation) for<br />

the Peel Commission’s Report. However,<br />

it is worth noting that the Balfour Declaration<br />

left intentionally vague the details of<br />

how Jewish the “national home” would<br />

be; other events – including those resulting<br />

from the work of Labor Zionists –<br />

must therefore be considered significant in<br />

the creation of a specifically Jewish State.<br />

One thing has been glaringly missing<br />

from the narrative so far: anti-Semitism in<br />

Europe. <strong>The</strong> impacts of anti-Semitism on<br />

the eventual creation of the State of Israel<br />

are wide-ranging. For one thing, Zionism<br />

as a form of nationalism developed – at<br />

least in part – out of necessity derived<br />

from anti-Semitism. Zionists such as <strong>The</strong>odore<br />

Herzl (considered so important to<br />

the Zionist cause that he was mentioned<br />

in the Declaration of Independence as part<br />

of the new State’s history) were inspired<br />

by anti-Semitic incidents: in the case of<br />

Herzl, the Dreyfus affair. Others, however,<br />

were not, including David Ben<br />

Gurion who in his 1970 memoirs wrote<br />

that “For<br />

many of [the<br />

“without the Labor Zionist ideology it<br />

would have been distinctly less possible<br />

for a Jewish State to be created”<br />

members of<br />

the Social-<br />

Democratic<br />

Jewish<br />

Workers'<br />

Party in<br />

Płońsk, Poland],<br />

anti-Semitic feeling had little to do<br />

with our dedication [to Zionism]”; this<br />

tells us that anti-Semitism was not the sole<br />

motivator of all European Zionists, even if<br />

anti-Semitism drove the majority. Furthermore,<br />

almost every wave of Aliyah can, at<br />

least in part but if not the most part, be ascribed<br />

to anti-Semitism: whether they be<br />

Russian pogroms or the rise of the Nazis.<br />

Unsurprisingly, when Jews were persecuted,<br />

they aimed to get out. As has already<br />

been discussed, the significant Jewish<br />

population in Mandatory Palestine<br />

was a major factor in the end of the Mandate<br />

and the ultimate creation of a Jewish<br />

State in Palestine; it cannot be denied that<br />

Jews (especially in waves of Aliyah during<br />

the Nazi era) were strongly motivated to<br />

emigrate by anti-Semitism and that many<br />

more Jews migrated to other countries<br />

than migrated to Israel while it was possible<br />

to do so; this would suggest that ideological<br />

motivations – such as those of Labor<br />

Zionists – were more significant factors<br />

in immigration to Israel than anti-<br />

Semitism as, when given the choice, most<br />

Jews did not act on any ideological motivations.<br />

However, anti-Semitism has existed in Europe<br />

for far longer than a millennium, or<br />

even two, and yet no Jewish State came to<br />

exist in Palestine until the mid-20 th Century.<br />

In fact, no Jewish State successfully<br />

came into existence anywhere, except the<br />

(very special) Kingdom of Beta Israel in<br />

Ethiopia, until the Jewish State of Israel;<br />

there were some proposals, safe cities and<br />

accidental Jewish Kings of ancient kingdoms,<br />

but no ‘Jewish State’. It is ultimately<br />

the case that the modern State of<br />

Israel only came about due to a convergence<br />

of many factors.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Labor Zionists<br />

were most<br />

significant when<br />

ensuring that<br />

these factors actually<br />

brought about<br />

a Jewish State: ensuring<br />

the British<br />

left and facilitating the creation of a Jewish<br />

State to – in part – replace it. <strong>The</strong>ir work<br />

relied upon the Political Zionists before<br />

them and was aided strongly by the persistent<br />

anti-Semitism across Europe, but<br />

without the Labor Zionist ideology it<br />

would have been distinctly less possible<br />

for a Jewish State to be created.<br />

Jacob, L6JRW

22 Individuals<br />

Was Henry VII really the king who<br />

created a new style of kingship?<br />

In a period when the art of kingship was constantly evolving, responsibility rested upon the king who<br />

wore the crown to innovate and modernise the role. Henry VII is widely considered to have brought a<br />

new style of kingship to fruition, but was he really as pioneering as many people believe?<br />

T<br />

he traditional, even slightly teleological<br />

argument goes like this.<br />

Henry VII came to power and dramatically<br />

began a dramatic change in the<br />

way kings governed the land. No longer<br />

would kings<br />

“He relied on his own<br />

central spies rather than<br />

fickle nobles to provide<br />

information”<br />

repeatedly<br />

go to war. Instead<br />

they<br />

would pursue<br />

peace.<br />

No longer<br />

would kings<br />

govern<br />

through the nobility and parliament. Instead<br />

they would have more direct control<br />

over the realm.<br />

Henry VII certainly did practice this type<br />

of kingship. Previous medieval kings<br />

such as Edward III and Henry V had<br />

taken the decision to go on grand foreign<br />

expeditions to France. Henry VII did not<br />

pursue an interest in regaining lands from<br />

France. He instead focussed on international<br />

diplomacy, such as his 1496 trade<br />

agreement with France. He also used foreign<br />

diplomacy to bring about domestic<br />

stability. Troublesome Margaret of Burgundy<br />

was exiled in the Netherlands and<br />

was aiding anti-Tudor activities in England.<br />

Instead of going to war with the<br />

Netherlands, he signed the Magnus Intercursus<br />

in 1496, a trade alliance that led to<br />

the Netherlands limiting her influence on<br />

English affairs.<br />

As a consequence of not having to go to<br />

war, the King did not need to raise<br />

money. This meant Henry VII became less<br />

reliant on Parliament, which had made it<br />

so much harder for previous kings to rule<br />

effectively such as the Long Parliament<br />

under Henry IV. Indeed, Henry VII only<br />

called Parliament seven times throughout<br />

his 24-year reign which gave him more<br />

power.<br />

His power was also strengthened by<br />

the way he behaved towards the nobility.<br />

He threatened them through<br />

forced bonds which meant they would<br />

not be rich enough to form great new<br />

private armies which had made them<br />

so powerful and problematic for previous<br />

kings. He also relied on his own central<br />

spies rather<br />

than fickle<br />

nobles to<br />

provide information,<br />

which was<br />

exceedingly<br />

useful, for instance<br />

when<br />

he used<br />

scouts to find<br />

out the plans<br />

of the Cornish<br />

rebels in<br />

1497. Of<br />

course, it<br />

should be<br />

noted that he<br />

changed noble<br />

relations,<br />

but not entirely<br />

in circumstances<br />

of his own making. <strong>The</strong><br />

Henry VII

23<br />

Wars of the Roses had significantly weakened<br />

the nobility due to the great killings<br />

that took place between noble families.<br />

It is tempting to say that Henry was the<br />

founder of this new<br />

kingship. After all,<br />

1485 marked the end<br />

of the ‘Wars of the<br />

Roses’ and brought a<br />

new dynasty to the<br />

throne. A new period<br />

of history, the<br />

Tudors, had begun and therefore surely<br />

that’s where the new style of kingship begun.<br />

New kingship, New England.<br />

In fact, however, Henry VII had probably<br />

drawn on Edward IV’s example of inform<br />

his new monarchy. During his second<br />

time on the throne, Edward IV had also<br />

employed a similar style of kingship. He<br />

had not fought foreign battles repeatedly.<br />

Instead, he went to France with an army<br />

“Henry VII shaped, crafted and<br />

accentuated the new kingship”<br />

began the use of spies, which he made<br />

great use of in 1466 to capture Henry VI.<br />

But maybe the original creator of this<br />

kingship came from a man nearly a century<br />

before Henry<br />

VII’s reign. Richard<br />

II was often seen as<br />

an unsuccessful and<br />

inept monarch who<br />

was deposed in 1399.<br />

Yet his style of kingship<br />

was certainly<br />

completely different to previous English<br />

monarchs. He pursued peace with France,<br />

which he achieved through his 1396 marriage<br />

that gave him a 28-year truce and<br />

£130 000. This made him less reliant on<br />

Parliament which he took great pleasure<br />

in not having to be dependent on anymore.<br />

He most certainly tried to bully the<br />

nobility. He forced the nobles to sign<br />

away all their lands to him in the late<br />

1390s and in 1397 killed three nobles who<br />

had angered him ten years back. He<br />

was trying to send a message to the nobility<br />

which conveyed his strength<br />

over them and his toughness against<br />

them. While his bullying ultimately<br />

backfired when Henry Bolingbroke,<br />

who he had expelled and disinherited,<br />

usurped him. But some aspects of his<br />

strategy such as peace with France was<br />

observed and acted upon by his successors<br />

many years later.<br />

Commemorative plaque<br />

for Cornish Rebellion in but came back with a treaty in<br />

Cornish and English, 1475 which gave him more<br />

Blackheath Common money and one less threat. Rather<br />

than relying on Parliament<br />

for money to pay off the debts left by his<br />

predecessors through taxation, he also relied<br />

on forced gifts which made Parliament<br />

less controlling. It was he who<br />

Henry VII’s son, Henry VIII, would<br />

build on his father’s legacy by breaking<br />

with Rome, furthering the power<br />

of the king – an incredibly significant<br />

milestone in changes to kingship.<br />

Henry VII certainly shaped, crafted<br />

and accentuated the ‘new kingship’.<br />

But it was not his creation entirely. Richard<br />

II and, more importantly, Edward IV<br />

were in fact significant players too in the<br />

foundation of this new style of monarchy.<br />

Sam OA

24 Individuals<br />

Gauchito Gil: <strong>The</strong> Cowboy<br />

Saint of Argentina<br />

G<br />

auchito Gil is an unofficial Catholic<br />

Saint from Corrientes, Argentina.<br />

Gauchito translates into ‘little<br />

gaucho’ in English. <strong>The</strong> gaucho was<br />

known to stand for the poor and good<br />