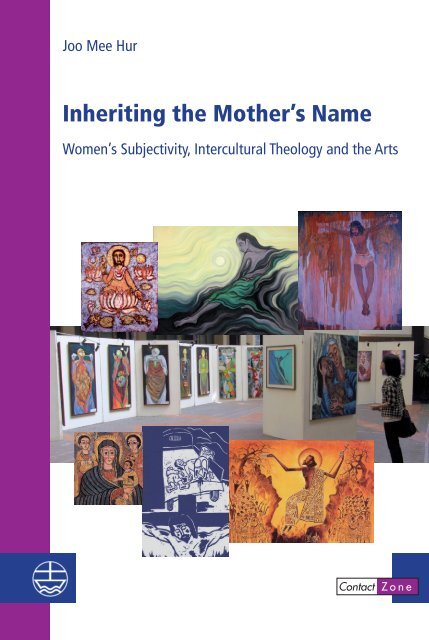

Joo Mee Hur: Inheriting the Mother’s Name (Leseprobe)

Christian women who put faith in action have been in solidarity with marginalized women in South Korea since the 1960s – most prominently, women workers since the 1960s, women victims of sexual violence since the 1970s, and women migrants since the 1990s. This volume focuses on the marginalized female marriage migrants and their experience of oppression. It analyses their socio-political context through a complementary subjective-objective approach and fosters a hermeneutics of empathy between Korean women and female marriage migrants based on historical scrutiny. In searching the scriptures Joo Mee Hur adapts intercultural theology for liberation, balancing between contextual hermeneutics and textual hermeneutics. Contrapuntally the author also opens a theological dialogue with the arts, which leads to a critical response and ethical commitment.

Christian women who put faith in action have been in solidarity with marginalized women in South Korea since the 1960s – most prominently, women workers since the 1960s, women victims of sexual violence since the 1970s, and women migrants since the 1990s. This volume focuses on the marginalized female marriage migrants and their experience of oppression. It analyses their socio-political context through a complementary subjective-objective approach and fosters a hermeneutics of empathy between Korean women and female marriage migrants based on historical scrutiny. In searching the scriptures Joo Mee Hur adapts intercultural theology for liberation, balancing between contextual hermeneutics and textual hermeneutics. Contrapuntally the author also opens a theological dialogue with the arts, which leads to a critical response and ethical commitment.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Joo</strong> <strong>Mee</strong> <strong>Hur</strong><br />

<strong>Inheriting</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mo<strong>the</strong>r’s <strong>Name</strong><br />

Women’s Subjectivity, Intercultural Theology and <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

Contact Zone

Content<br />

Introduction 7<br />

Chapter 1<br />

The Poor and Minjung. Sociological and<br />

Theological Perspectives<br />

1. Religion of Illusory Happiness 13<br />

2. The Poor in a Christian World 17<br />

3. Minjung in a Multi-religious World 23<br />

Conclusion 34<br />

Chapter 2<br />

The Female Face of Minjung. Han-pu-ri and <strong>the</strong> Subjective-<br />

Objective Approach<br />

1. Methodologies of Third World Theologies 37<br />

2. Oppression against Women 46<br />

Conclusion 56<br />

Chapter 3<br />

The Emergence of Female Marriage Migrants in Korea. Contextual<br />

Transformations, New Subjects and Continuing Oppression<br />

1. Minjung in our Times? 59<br />

2. The Increase of Female Marriage Migrants 62<br />

3. Female Marriage Migrants in Agony 64<br />

4. The Decline in International Marriages 78<br />

Conclusion 81

6 Content<br />

Chapter 4<br />

Literature, Contrapuntality and Confluence of<br />

two Traditions. Aes<strong>the</strong>tic Perspectives<br />

1. Literature as Source of Theology 83<br />

2. Contrapuntal Reading 92<br />

3. Confluence toward Theology of Liberation 101<br />

Conclusion 104<br />

Chapter 5<br />

A Theological Dialogue between Film and Bible.<br />

Aes<strong>the</strong>tic Perspectives<br />

1. Interaction between Text and Context 107<br />

2. Film and Biblical Narrative 111<br />

3. Contrapuntal Reading 114<br />

Conclusion 127<br />

Chapter 6<br />

New Faces of Minjung, Liberation Hermeneutics and <strong>the</strong><br />

Reign of God. Biblical and Theological Perspectives<br />

1. Bible for <strong>the</strong> Oppressed 129<br />

2. Hermeneutics for <strong>the</strong> Liberation of Female Marriage Migrants 138<br />

3. Reign of God and Human Action 150<br />

Conclusion 155<br />

Chapter 7<br />

Faith, Action and Subjectivity. Ethical Perspectives<br />

1. The Female Face of Minjung 159<br />

2. Faith and Action 160<br />

3. Subjectivity 176<br />

Conclusion 179<br />

Bibliography 181

Introduction<br />

Sometimes I was not convinced of what I have learned in <strong>the</strong>ological<br />

seminary. When prosperity and success were mentioned as a privilege<br />

which Christians could enjoy in <strong>the</strong>ir lives, I cannot accept it easily<br />

when I think of <strong>the</strong> pain in people’s lives. In response to my doubts<br />

about <strong>the</strong> promise of prosperity and success it was corrected as to be a<br />

spiritual one. However, people’s pain on earth has been neglected by<br />

<strong>the</strong> traditional <strong>the</strong>ologies. My doubts still remained with me, but I did<br />

not talk about it any fur<strong>the</strong>r. Honestly, I was not sure exactly what<br />

questions or doubts I had at that time. Yet I had <strong>the</strong> impression that<br />

<strong>the</strong>ology might not answer my questions properly.<br />

Sometimes I felt very uncomfortable when sitting in <strong>the</strong> pews listening<br />

to sermons from <strong>the</strong> pulpit. When <strong>the</strong> biblical stories related to<br />

women were told, I was annoyed as a woman by <strong>the</strong> way those stories<br />

unfolded or by <strong>the</strong> biblical or pastoral interpretations of those stories.<br />

At such times, I wondered if it is only me who was annoyed with what<br />

I heard and I used to have a look around carefully. Women were <strong>the</strong><br />

majority of <strong>the</strong> congregation, but I could not read any embarrassment<br />

on <strong>the</strong>ir faces with those sermons. I was not sure exactly what was<br />

annoying me, but this happened to me often.<br />

Maybe I have followed <strong>the</strong> wrong path and it might not be too late<br />

to find o<strong>the</strong>r paths. “Let’s leave quietly, without making any noise.”<br />

When I almost lost my interest in <strong>the</strong>ology, I have been introduced to<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r kinds of <strong>the</strong>ology. There are concerns about <strong>the</strong> issues of <strong>the</strong><br />

secular life and about <strong>the</strong> comprehensive understanding of <strong>the</strong> reign of<br />

God not only in heaven but also on earth. I was hooked on to <strong>the</strong>m<br />

immediately. They have helped me to understand what questions I<br />

have. I used to hesitate to proclaim any spiritual blessing, with ignoring<br />

<strong>the</strong> pains of <strong>the</strong> people on earth. I just want to be able to say that<br />

we are blessed and at <strong>the</strong> same time we still have pains to be solved.<br />

After entering into eternity, it will not be a problem anymore but be-

8 Introduction<br />

fore that, how do we deal with <strong>the</strong> pains in our lives, which are extremely<br />

short compared to eternity? 1 I have started to know how to<br />

name <strong>the</strong> irritations I have had. It turned out that <strong>the</strong>y were violence to<br />

hurt o<strong>the</strong>rs. This is also called oppression, or more specifically, sexism,<br />

classism, racism, etc. 2<br />

Since 1993, Korean Chinese Women started to immigrate to<br />

South Korea through international marriage by reason of “<strong>the</strong> relief of<br />

Korean single farmers”. 3 In <strong>the</strong> 2000s <strong>the</strong> rate of international marriages<br />

between poor Korean men in urban and rural areas, and women<br />

coming from o<strong>the</strong>r Asian countries began to increase as <strong>the</strong> target<br />

range for foreign spouses of Korean men has been extended into<br />

Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia. 4 It has often been reported that many migrant brides<br />

are experiencing a wide variety of oppression and discrimination in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir marriage process and marriage life. This is based not only on <strong>the</strong><br />

needs of bride’s parents who would marry off <strong>the</strong>ir daughter to Korean<br />

men but also of groom’s parents who would take a daughter-in-law<br />

from abroad through international marriage brokers who are interested<br />

in making profits. 5 With its patriarchal, sexist and racial discrimination<br />

against women, this perilous phenomenon calls attention not only<br />

of social scientists but also of pastors, missionaries and <strong>the</strong>ologians in<br />

faith communities. For my master <strong>the</strong>sis, I was inspired to write about<br />

<strong>the</strong> oppression of women in my context in our times and I have been<br />

doing research on issues related to female marriage migrants since<br />

<strong>the</strong>n. 6<br />

In 1988, feminist <strong>the</strong>ologians Katie Geneva Cannon, Ada Maria<br />

Isasi-Diaz, Kwok Pui-lan and Letty M. Russell edited a volume titled,<br />

1<br />

See Chapter 1.<br />

2<br />

The term classism is casually used in <strong>the</strong>se listings for what I would ra<strong>the</strong>r call social injustice.<br />

3<br />

Han Kuk-yeom, 우리 모두는 이방인이다: 사례로 보는 이주여성인권운동 15 년 (We are all<br />

Strangers: 15 years of Women Migrants’ Human Rights Movement in Korea), Paju 2017, 31.<br />

4<br />

Ibid. Part of an earlier version of this paragraph has been published in 결혼이주여성을 중심으로<br />

읽는 로안과 룻의 이야기 (The Story of Loan and Ruth in light of Female Marriage Migrants, in:<br />

민중신학의 여정 (Minjung Theology: A Journey Toge<strong>the</strong>r), <strong>the</strong> Korean Society of Minjung<br />

Theology (ed.), Seoul, 2017, 242–265 and Film und Theologie treiben im Heute. Loan und<br />

Ruth, stories zweier Heiratsmigrantinnen, in: Theologie und Kunst unterrichten, Volker Küster<br />

(ed.), Leipzig, 2021, 235–252.<br />

5<br />

Han, We are all Strangers, 31f.<br />

6<br />

<strong>Joo</strong>mee <strong>Hur</strong>, Our Brown Mo<strong>the</strong>rs: Migrant Marriage Women in South Korea from Minjung<br />

Perspective, unpublished Master<strong>the</strong>sis, Kampen 2011. I thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c.<br />

Volker Küster for encouraging me to develop this fur<strong>the</strong>r into a PhD-project; it has become<br />

<strong>the</strong> seed of <strong>the</strong> current book.

<strong>Inheriting</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mo<strong>the</strong>r’s <strong>Name</strong> 9<br />

<strong>Inheriting</strong> our Mo<strong>the</strong>r’s Gardens: Feminist Theology in Third World<br />

Perspective. The collected articles include autobiography as a method<br />

to talk about <strong>the</strong> stories of authors’ mo<strong>the</strong>rs and grandmo<strong>the</strong>rs related<br />

to <strong>the</strong>ological discussions. 7 The female authors have decided to inherit<br />

<strong>the</strong> lessons critically from <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>rs. This reminds me of my<br />

inheritance from my own mo<strong>the</strong>r and grandmo<strong>the</strong>rs. I inherited my<br />

surname from my fa<strong>the</strong>r’s side, but it has a very unique story regarding<br />

its origin. The progenitor of my family name was not a man but a<br />

woman. Besides, she was a stranger, who has been known to come<br />

from India. In Korea, children follow traditionally <strong>the</strong>ir fa<strong>the</strong>r’s surname,<br />

but women do not change <strong>the</strong>ir surname after marriage and<br />

keep <strong>the</strong>m. However, children of single mo<strong>the</strong>rs can follow <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r’s surnames since <strong>the</strong> abolition of <strong>the</strong> Patriarchal Family Register<br />

System Act in 2005. 8 In Korean history, <strong>the</strong>re is only one exceptional<br />

case, as far as I know. It is <strong>the</strong> surname Hŏ (Heo, Huh, <strong>Hur</strong>, etc.<br />

various spellings in English, 허 in Korean character and 許 in Chinese<br />

character), which is taken up as <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r’s surname in <strong>the</strong> ancient<br />

history of Korea, even though it has never been repeated but happened<br />

one time only with <strong>the</strong> progenitor.<br />

According to <strong>the</strong> foundation myth of Kingdom Gaya (Samkuk<br />

yusa [Memorabilia of <strong>the</strong> Three Kingdoms], Part 2.23 “Karak kukki”),<br />

King Kim Suro was married to a princess Hŏ Hwangok from Ayut’aguk,<br />

“<strong>the</strong> ancient Indian city of Ayodhya near Faizabad, Utta Pradesh<br />

State” in AD 48. 9 Her Indian name was Suriratna and her name was<br />

changed to Hŏ Hwangok after marriage. 10 Queen Hŏ gave birth to ten<br />

sons and <strong>the</strong> first son took <strong>the</strong>ir fa<strong>the</strong>r’s surname Kim and two sons<br />

took <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>r’s surname Hŏ and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r seven sons became<br />

Buddhist monks. 11 My progenitor was a female marriage migrant two<br />

thousand years ago in our land. Korea used to be known as a homoge-<br />

7<br />

Letty M. Russell, Kwok Pui-lan, Ada Maria Isasi-Diaz and Katie Geneva Cannon (eds),<br />

<strong>Inheriting</strong> Our Mo<strong>the</strong>r’s Gardens: Feminist Theology in Third World Perspective, Louisville<br />

1988, 15.<br />

8<br />

Chan S. Suh, Eun Sil Oh, and Yoon S. Choi, The Institutionalization of <strong>the</strong> women’s movement<br />

and gender legislation, in: South Korea Social Movements: From Democracy to Civil<br />

Society, Gi-Wook Shin and Paul Y. Chang (eds), London and New York 2011, 151–169.<br />

9<br />

James Huntley Grayson, Myths and Legends from Korea: An Annotated Compendium of<br />

Ancient and Modern Materials, London and New York 2001, 26, 110f, 113; Cf. Choong Soon<br />

Kim, Voices of Foreign Brides: The Roots and Development of Multiculturalism in Korea,<br />

Lanham, Maryland 2011, 25–47.<br />

10<br />

Kishore Kunal, Ayodhyā Revisited, New Delhi 2016, 26.<br />

11<br />

https://yongin.grandculture.net/Contents?local=yongin&dataType=01&contents_id=GC009<br />

01250 (accessed on Jan. 21, 2020).

10 Introduction<br />

nous country ethnically, but it will not be easy to maintain that claim<br />

when we look back in our history.<br />

When I as a Korean woman see <strong>the</strong> agony of female marriage migrants,<br />

I cannot see <strong>the</strong>m simply as strangers. Many female marriage<br />

migrants in our history have already belonged to us, Korean women.<br />

The historical scrutiny on female marriage migrants shortens <strong>the</strong> distance<br />

between female marriage migrants and Korean women. The<br />

matters of female marriage migrants are not those of o<strong>the</strong>rs, but <strong>the</strong>y<br />

became our matters to take care of toge<strong>the</strong>r with empathy. It has been<br />

<strong>the</strong> stories of our mo<strong>the</strong>rs and grandmo<strong>the</strong>rs and of our neighbors<br />

alike.<br />

The prominent postcolonial critic Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak<br />

raised <strong>the</strong> famous question, Can <strong>the</strong> subaltern speak? 12 Many readers<br />

of her essay about this question have been disappointed with her conclusion<br />

that <strong>the</strong> subaltern cannot speak, but she answered in an interview<br />

with Donna Landry and Gerald Mclean that it means how difficult<br />

it is for <strong>the</strong> gendered subaltern to speak and to be heard. 13 Spivak<br />

even suggested <strong>the</strong> agency of <strong>the</strong> post-colonial intellectual for subaltern’s<br />

public speech acts. 14 However, it is still a reminder to be careful<br />

about o<strong>the</strong>rs in taking <strong>the</strong> role of agency. I try to create a space of empathy<br />

to shorten <strong>the</strong> distance between subaltern and o<strong>the</strong>rs and develop<br />

a hermeneutics of empathy in understanding our experiences. It<br />

reminds me of Jesus’ identification with <strong>the</strong> oppressed in Mat<strong>the</strong>w 25.<br />

This dissertation consists of 7 chapters. Chapter 1 revisits Karl<br />

Marx’s famous notion, that religion is <strong>the</strong> opium of <strong>the</strong> people. It focuses<br />

on his observation that religion can be seen not only as illusion<br />

but also as liberation. 15 I accept his criticism and negative definition<br />

of religion as an illusory happiness, but I embrace his positive definition<br />

of religion as a humanistic impulse at <strong>the</strong> same time. I connect<br />

this with Christian <strong>the</strong>ology, especially liberation <strong>the</strong>ology in Latin<br />

America and minjung <strong>the</strong>ology in South Korea. I look into <strong>the</strong>ir main<br />

concepts such as <strong>the</strong> poor, oppression, minjung and han. It shows how<br />

liberation <strong>the</strong>ology has enhanced <strong>the</strong> liberation aspects for <strong>the</strong> oppressed<br />

within Christianity.<br />

12<br />

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Can <strong>the</strong> Subaltern Speak?, in: Marxism and <strong>the</strong> Interpretation<br />

of Culture, Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (eds), Urbana, Illinois 1988, 271–313.<br />

13<br />

Stephen Morton, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (b. 1942), in: From Agamben to Žižek: Contemporary<br />

Critical Theorists, Jon Simons (ed.), Edinburgh 2010, 210–226, 218.<br />

14<br />

Ibid.<br />

15<br />

Denys Turner, Religion: Illusions and liberation, in: The Cambridge Companion to Marx,<br />

Terrell Carver (ed.), Cambridge 1991, 320–337.

<strong>Inheriting</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mo<strong>the</strong>r’s <strong>Name</strong> 11<br />

Chapter 2 introduces <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ological methodologies to reflect on<br />

<strong>the</strong> socio-political realities of <strong>the</strong> oppressed, which have been applied<br />

by third world <strong>the</strong>ologies. I look into <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ological methodologies<br />

adopted by minjung <strong>the</strong>ology and Asian women’s <strong>the</strong>ology, and I<br />

suggest <strong>the</strong> complementary subjective-objective approach to analyze<br />

my context by combining Han-pu-ri and social biography: each stresses<br />

<strong>the</strong> storytelling of <strong>the</strong> voiceless and <strong>the</strong> social analysis including <strong>the</strong><br />

connectivity between <strong>the</strong> past, <strong>the</strong> present and <strong>the</strong> future. Before entering<br />

into <strong>the</strong> current context in Chapter 3, I examine <strong>the</strong> oppressions<br />

against women in <strong>the</strong> history of Korea since <strong>the</strong> Chosun dynasty (late<br />

fourteenth to early twentieth century’s) to <strong>the</strong> 1980s. I listen to <strong>the</strong><br />

stories of Korean women under <strong>the</strong> patriarchal system of Confucianism,<br />

military sexual slavery by Japan, military brides in America,<br />

nurses dispatched to West Germany, and women in urban squats and<br />

women workers as representatives of <strong>the</strong> oppressed groups.<br />

Chapter 3 examines <strong>the</strong> validity of <strong>the</strong> term minjung of <strong>the</strong> 1970s<br />

and 1980s in our times (<strong>the</strong> 2000s and <strong>the</strong> 2010s). Minjung <strong>the</strong>ologians<br />

and minjung communities have not confined this so-called outdated<br />

term minjung to <strong>the</strong> faces of minjung in <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 1980s and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have paid attention to <strong>the</strong> new faces of minjung <strong>the</strong>reafter. Female<br />

marriage migrants emerged as <strong>the</strong> new faces of minjung since<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1990s. I scrutinize <strong>the</strong>ir socio-political situations by using <strong>the</strong> subjective-objective<br />

approach, which has been introduced in <strong>the</strong> previous<br />

chapter. By telling <strong>the</strong> stories of Korean women in Chapter 2 and<br />

those of migrant women in Chapter 3, a space of empathy is cultivated.<br />

Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 participate in <strong>the</strong>ological dialogue with<br />

<strong>the</strong> arts, producing a critical response and fostering a hermeneutics of<br />

empathy. First, chapter 4 discusses how literature has been used as<br />

source of <strong>the</strong>ology, in particular in dialogue between minjung <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

and minjung literature, and between womanist <strong>the</strong>ology and black<br />

women’s religious narratives. I read contrapuntally two stories of migrant<br />

brides, one is a Vietnamese migrant bride in South Korea and<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is a Korean picture bride in Hawaii. This contrapuntal reading<br />

broadens <strong>the</strong> hermeneutical horizon and deepens <strong>the</strong> analysis,<br />

where <strong>the</strong> discourses of liberation or that of domination will be detected.<br />

Chapter 5 initiates a dialogue between film and bible. It is ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

kind of contrapuntal reading of a short film and a biblical narrative,<br />

<strong>the</strong> book of Ruth, which both deal with <strong>the</strong> issue of female marriage<br />

migrants. This encounter starts with <strong>the</strong> similarities between <strong>the</strong>m, but<br />

it develops to compare difference between <strong>the</strong>m as well, and it offers

12 Introduction<br />

us a more critical analysis of social issues related to female marriage<br />

migrants. I follow Chung Hyun-Kyung’s bold claim to reverse our life<br />

as our text and <strong>the</strong> bible and church tradition as <strong>the</strong> context as an<br />

Asian feminist <strong>the</strong>ologian. It is contextual hermeneutics ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

textual hermeneutics. The hermeneutical demand for our life cannot<br />

be confined in <strong>the</strong> solutions which were formulated only in <strong>the</strong> context<br />

of <strong>the</strong> biblical text and its traditional textual interpretations, but <strong>the</strong><br />

context of <strong>the</strong> reader should be considered seriously.<br />

Chapter 6 articulates <strong>the</strong> biblical interpretation for female marriage<br />

migrants. In <strong>the</strong> postcolonial era, South Korean people have a<br />

double identity not only as <strong>the</strong> victimized but also <strong>the</strong> victimizer and<br />

we should make our effort to decolonize oppressive situations from<br />

both positions with <strong>the</strong> current social issues in a globalized era. From<br />

<strong>the</strong> new position as <strong>the</strong> victimizer, we still need to consider which<br />

stance to take on a certain issue. Regarding this, I will seek <strong>the</strong> advice<br />

from <strong>the</strong> past by introducing two opposite stances, pro-slavery ideology<br />

and anti-slavery ideology among Christian ministers in pre-Civil<br />

War America. In response, I will take a stance toward liberation hermeneutics<br />

for female marriage migrants. I will collect <strong>the</strong> liberating<br />

messages against <strong>the</strong> oppressions which female marriage migrants are<br />

experiencing from <strong>the</strong> Scriptures and <strong>the</strong>ological discourses. The liberation<br />

hermeneutics reminds us of <strong>the</strong> reign of God on earth and its<br />

relation to human action.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> final Chapter 7, I focus on Christian women who have<br />

stood with <strong>the</strong> oppressed since <strong>the</strong> 1960s in South Korea. The liberation<br />

project in Christianity does not stop in changing <strong>the</strong> way we think<br />

only by articulating a <strong>the</strong>ology of liberation but it becomes action,<br />

especially by women in our Christian history. The face of female<br />

minjung has been changed and <strong>the</strong>ir faces from each time period will<br />

be introduced along with those of Christian women who have stood in<br />

solidarity with <strong>the</strong>m including <strong>the</strong>ir oppressions and liberations. Subjectivity<br />

will be suggested as one of <strong>the</strong> virtues we should pursue in<br />

<strong>the</strong> struggle for liberation of <strong>the</strong> oppressed.

Chapter 1<br />

The Poor and Minjung.<br />

Sociological and Theological Perspectives<br />

When we contemplate about a Christianity for everyone, regardless of<br />

class, gender, race, etc., we do not need to start from zero. We cannot<br />

claim that <strong>the</strong> main concern of Christianity has been <strong>the</strong> least of our<br />

bro<strong>the</strong>rs and sisters in its history but <strong>the</strong>re always have been people of<br />

faith with warm attention towards <strong>the</strong>m, in spite of <strong>the</strong>ir minority<br />

standing. I try to examine this legacy of our predecessors in faith. My<br />

models do not come from <strong>the</strong> remote past but from recent history. I<br />

will limit my scope to liberation <strong>the</strong>ology in Latin America and<br />

minjung <strong>the</strong>ology in South Korea. As one of <strong>the</strong> external influences to<br />

have challenged <strong>the</strong>se liberation <strong>the</strong>ologies, I will revisit Karl Marx’s<br />

criticism of religion (of illusory happiness) first. Even though Marx’s<br />

criticism of religions has been well known, I will focus here on religion<br />

of liberation as <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r side of his criticism of religion.<br />

1. Religion of Illusory Happiness<br />

Karl Marx (1818–1883) is well known for his remark about religion,<br />

“Sie ist das Opium des Volks (It is <strong>the</strong> opium of <strong>the</strong> people).” 1 This<br />

famous statement has been excerpted from his article, Zur Kritik der<br />

Hegel’schen Rechts-Philosophie (Towards a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy<br />

of Right) published in 1844 in <strong>the</strong> Deutsch-Französische<br />

Jahrbücher (German-French Yearbooks). The first two pages of this<br />

article left us his brief but critical stance on religion. Even though<br />

Marx did not write much about religion in it, he never<strong>the</strong>less regarded<br />

<strong>the</strong> criticism of religion as <strong>the</strong> prerequisite to all criticism of Germany<br />

1<br />

Karl Marx, Zur Kritik der Hegel’schen Rechtsphilosophie von K. Marx, in: Deutschfranzösische<br />

Jahrbücher, Arnold Ruge und Karl Marx (eds), Paris 1844, 71–85, 72.

14 Chapter 1<br />

in his times. 2 Marx used <strong>the</strong> comprehensive concept religion instead<br />

of referring to certain religions which he has been accustomed to in<br />

his context such as Christianity, Judaism, etc. Yet <strong>the</strong> domain of religion<br />

that Marx argued with seems to have been very much limited,<br />

compared to an inclusive concept of <strong>the</strong> world religions in <strong>the</strong> 21 st<br />

century.<br />

Marx did not point to <strong>the</strong> specific religions but his criticism was<br />

directed against religions offering “die phantastische Wirklichkeit des<br />

Himmels (<strong>the</strong> imaginary reality of heaven)” instead of “die wahre<br />

Wirklichkeit (<strong>the</strong> true reality of <strong>the</strong> earths).” 3 The religions of <strong>the</strong> imaginary<br />

reality are also described as “des illusorischen Glücks des<br />

Volks (<strong>the</strong> illusory happiness of <strong>the</strong> people)” and this expression helps<br />

us to understand better his famous metaphor, religion as <strong>the</strong> opium of<br />

<strong>the</strong> people. 4 But, opium is not only known as <strong>the</strong> source of <strong>the</strong> highly<br />

addictive drug but also of a potent pain reliever for centuries. 5 Morphine<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r opiates, which are extracted, isolated, and purified<br />

from opium are prescribed by doctors to relieve severe pain of <strong>the</strong><br />

patient such as after injury or major surgery today. 6 These two faces<br />

of opium hinder <strong>the</strong> reader from interpreting Marx’s opium metaphor.<br />

If we pay attention more to <strong>the</strong> expression “illusory happiness”, <strong>the</strong><br />

opium metaphor seems to imply <strong>the</strong> negative aspect of religion as illusion.<br />

7<br />

However, Marx also presents us his definition of religion as <strong>the</strong><br />

true reality of <strong>the</strong> earth and within it <strong>the</strong>re is no place for <strong>the</strong> religions<br />

talking about <strong>the</strong> imaginary reality of heaven and <strong>the</strong> illusory happiness<br />

of people. To him, “der Seufzer der bedrängten Kreatur (<strong>the</strong> sigh<br />

of <strong>the</strong> oppressed creature)”, “die herzlose Welt (a heartless world)”<br />

and “geistloser Zustände (<strong>the</strong> spiritless situation)” are much more important<br />

than <strong>the</strong> people of <strong>the</strong> illusory happiness in <strong>the</strong> imaginary<br />

heaven. 8<br />

Das religiöse Elend ist in einem der Ausdruck des wirklichen Elendes und in<br />

einem die Protestation gegen das wirkliche Elend. Die Religion ist der Seuf-<br />

2<br />

Op. cit., 71.<br />

3<br />

Ibid.<br />

4<br />

Op. cit., 72.<br />

5<br />

M. Foster Olive, Prescription Pain Relievers, New York 2005, 36.<br />

6<br />

Op. cit., 40.<br />

7<br />

Marx, Deutsch-französische Jahrbücher, 72.<br />

8<br />

Op. cit., 71f.; The English Translation from Karl Marx, Contribution to <strong>the</strong> Critique of<br />

Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. Introduction, in: On Religion, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels<br />

(eds), Chico, Calif., 1964, 42.

The Poor and Minjung 15<br />

zer der bedrängten Kreatur, das Gemüth einer herzlosen Welt, wie sie der<br />

Geist geistloser Zustände ist. Sie ist das Opium des Volks (Religious distress<br />

is at <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>the</strong> expression of real distress and <strong>the</strong> protest against real<br />

distress. Religion is <strong>the</strong> sigh of <strong>the</strong> oppressed creature, <strong>the</strong> heart of a heartless<br />

world, just as it is <strong>the</strong> spirit of a spiritless situation. It is <strong>the</strong> opium of <strong>the</strong><br />

people). 9<br />

According to him, religion embodies <strong>the</strong> “Ausdruck des wirklichen<br />

Elendes (<strong>the</strong> expression of real misery)” and “die Protestation gegen<br />

das wirkliche Elend (<strong>the</strong> protest against real misery).” 10 If we listen to<br />

his description of religion as <strong>the</strong> true reality of <strong>the</strong> earth, <strong>the</strong> opium<br />

metaphor seems to express <strong>the</strong> positive aspect of religion as liberation.<br />

11<br />

When we puzzle with his metaphor, he draws a bit hasty conclusions<br />

about people who have religious beliefs. Marx did not stop just<br />

to criticize <strong>the</strong> religions of <strong>the</strong> imaginary reality or <strong>the</strong> illusory happiness<br />

and claimed radically to discard it through his metaphor of <strong>the</strong><br />

chain and <strong>the</strong> flowers.<br />

Die Kritik hat die imaginären Blumen an der Kette zerpflückt, nicht damit<br />

der Mensch die phantasielose, trostlose Kette trage, sondern damit er die<br />

Kette abwerfe und die lebendige Blume breche (Criticism has plucked <strong>the</strong><br />

imaginary flowers from <strong>the</strong> chain not so that man will wear <strong>the</strong> chain without<br />

any fantasy or consolation but so that he will shake off <strong>the</strong> chain and cull <strong>the</strong><br />

living flower). 12<br />

Next, he argued that it is <strong>the</strong> religions of <strong>the</strong> illusory happiness which<br />

prevent people from <strong>the</strong> life of reason. He urges man not to revolve<br />

round religion, “die illusorische Sonne (illusory sun)”, but to revolve<br />

round himself and round “seine wirkliche Sonne (his true sun)”.<br />

Die Kritik der Religion enttäuscht den Menschen, damit er denke, handle,<br />

seine Wirklichkeit gestalte, wie ein enttäuschter, zu Verstand gekommener<br />

Mensch, damit er sich um sich selbst und damit um seine wirkliche Sonne<br />

bewege. Die Religion ist nur die illusorische Sonne, die sich um den<br />

Menschen bewegt, so lange er sich nicht um sich selbst bewegt (The criticism<br />

of religion disillusions man to make him think and act and shape his reality<br />

like a man who has been disillusioned and has come to reason, so that he will<br />

revolve round himself and <strong>the</strong>refore round his true sun. Religion is only <strong>the</strong><br />

9<br />

Ibid.<br />

10<br />

Marx, Deutsch-französische Jahrbücher, 71.<br />

11<br />

Turner, Illusions and liberation, 333.<br />

12<br />

Marx, Deutsch-französische Jahrbücher, 72; Marx, Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,<br />

42.

16 Chapter 1<br />

illusory sun which revolves round man as along as he does not revolve round<br />

himself). 13<br />

Then, he underscored <strong>the</strong> task of history, philosophy, law and politics<br />

to establish “die Wahrheit des Diesseits (<strong>the</strong> truth of this world)”,<br />

while “das Jenseits der Wahrheit (<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r world of truth)” is to be<br />

gone, that is understood as <strong>the</strong> task of religion and <strong>the</strong>ology. 14 It is<br />

clear that he demanded <strong>the</strong> immediate turnabout from <strong>the</strong> way for <strong>the</strong><br />

truth of <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r world to <strong>the</strong> way for <strong>the</strong> truth of this world. To him,<br />

religion is understood as <strong>the</strong> chain to be thrown away, giving <strong>the</strong> people<br />

<strong>the</strong> illusion in <strong>the</strong> afterlife, without giving <strong>the</strong> liberation in this<br />

earthly life. In fact, he claimed <strong>the</strong> abolition of religion.<br />

Taking into account Marx’s context in <strong>the</strong> Germany of <strong>the</strong> 19 th<br />

century, <strong>the</strong> religion Marx criticized would be Christianity, though, in<br />

a broad sense, any religion could be included as object of his criticism<br />

if offering <strong>the</strong> people, <strong>the</strong> illusion of heaven without <strong>the</strong> liberation on<br />

earth. Marx presented not only <strong>the</strong> abolition of religion as illusion but<br />

also <strong>the</strong> affirmation of religion as liberation. His radical conclusion to<br />

abolish religion is hard to accept for anyone with any religious tradition.<br />

Yet his criticism, not as a whole but as a selective modification,<br />

has been accommodated by anyone who attempts to reform <strong>the</strong>ir religious<br />

tradition based on <strong>the</strong> humanitarian motivation inspired by him.<br />

Besides, <strong>the</strong>re is an eschatological tension regarding <strong>the</strong> reign of God<br />

between now already on earth and not yet in heaven in Christian faith,<br />

especially refocused and reinterpreted by Jesus Christ. 15 If Christianity<br />

is talking only about <strong>the</strong> imaginary reality in <strong>the</strong> afterlife as Marx<br />

pointed out, it fails to teach one of <strong>the</strong> most important Christian doctrines,<br />

<strong>the</strong> incarnation of God or <strong>the</strong> divine presence (or intervention)<br />

in history in its religious tradition and practice. Marx offers <strong>the</strong> religious<br />

reformists, especially in Christianity a useful impulse to reflect<br />

on <strong>the</strong>mselves in terms of <strong>the</strong> reality of <strong>the</strong> earth and to redirect <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

religion into <strong>the</strong> way of balance concerning <strong>the</strong> eschatological tension.<br />

The ideal religion described above by Marx can be reaffirmed and<br />

practiced within Christianity at <strong>the</strong>ir own free will without <strong>the</strong> elimination<br />

of religion. The major rationale behind Marx’s criticism is that<br />

religion is an illusion provider. Therefore, two tasks are given for<br />

Christians who are willing to converse with his criticism to complete:<br />

13<br />

Marx, Deutsch-französische Jahrbücher, 72; Marx, Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,<br />

42.<br />

14<br />

Marx, Deutsch-französische Jahrbücher, 72.<br />

15<br />

Cf. Volker Küster, The Many Faces of Jesus Christ, Maryknoll, NY 2001, 144f.

The Poor and Minjung 17<br />

one is to be a liberation provider and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is to present <strong>the</strong> feasible<br />

truth of heaven as an extension of <strong>the</strong> true reality of <strong>the</strong> earths.<br />

2. The Poor in a Christian World<br />

Who takes <strong>the</strong> initiative in <strong>the</strong> process of liberation in <strong>the</strong> Christian<br />

community? 16 Gustavo Gutiérrez suggests that it is <strong>the</strong> poor that initiate<br />

this process, and he refers to that process as “<strong>the</strong> irruption of <strong>the</strong><br />

poor.” 17 Not only in <strong>the</strong> society but also in <strong>the</strong> church <strong>the</strong> poor had<br />

been of little or no significance but <strong>the</strong>y have come to reveal <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

situations as active agents in <strong>the</strong> decades before <strong>the</strong> rise of <strong>the</strong> basic<br />

church communities in Latin America as well as in o<strong>the</strong>r third world<br />

countries and even among <strong>the</strong> racial and ethnic minorities and <strong>the</strong><br />

poor of rich nations. Then <strong>the</strong>ologians began critically reflecting on<br />

this historical event in order to read <strong>the</strong> sign of <strong>the</strong> times in a <strong>the</strong>ological<br />

register. 18 This commitment has brought a new <strong>the</strong>ological perspective<br />

to Christianity.<br />

Liberation <strong>the</strong>ology speaks of salvation in terms of liberation and<br />

<strong>the</strong>reby strives to balance concerns for life after death with concerns<br />

for life on earth. The latter has received much less attention in <strong>the</strong> history<br />

of Christianity. Liberation <strong>the</strong>ology treats human beings not only<br />

as sinners who violate God’s law (personal sin) but also as victims<br />

who are violated by structural sin. 19 The concept of <strong>the</strong> poor in liberation<br />

<strong>the</strong>ology thus applies to anyone suffering from <strong>the</strong> various oppressions.<br />

20<br />

Orthopraxis<br />

An encounter between <strong>the</strong> Catholic Church and <strong>the</strong> poor in Latin<br />

America can be found in <strong>the</strong> basic church communities. Leonardo<br />

16<br />

Part of this chapter was published as Faith, Action, and Subjectivity: The Social Engagement<br />

of Christian Women in South Korea, in: Theologies on <strong>the</strong> Move: Religion, Migration,<br />

and Pilgrimage in <strong>the</strong> World of Neoliberal Capital, Joerg Rieger (ed.), Lanham 2020, 73–89.<br />

17<br />

Gustavo Gutiérrez, The Irruption of <strong>the</strong> Poor in Latin America and <strong>the</strong> Christian Communities<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Common People, in: The Challenge of Basic Christian Communities: Papers from<br />

<strong>the</strong> International Ecumenical Congress of Theology, February 20-March 2, 1980, Sao Paulo,<br />

Brazil, Sergio Torres and John Eagleson (eds), Maryknoll, NY 1981, 107–123, 107f.; Gustavo<br />

Gutiérrez, Option for <strong>the</strong> Poor, in: Systematic Theology: Perspectives from Liberation Theology,<br />

Jon Sobrino and Ignacio Ellacuría (eds), Maryknoll, NY 1996, 22–37, 22f.<br />

18<br />

Gutiérrez, The Irruption of <strong>the</strong> Poor, 108–110; Gutiérrez, Option for <strong>the</strong> Poor, 22f.<br />

19<br />

Raymond Fung, Compassion for <strong>the</strong> Sinned Against, Theology Today 37, no. 2 (July 1980),<br />

162–169, 162.<br />

20<br />

Gutiérrez, The Irruption of <strong>the</strong> Poor, 111f.; Gutiérrez, Option for <strong>the</strong> Poor, 23f.

Chapter 2<br />

The Female Face of Minjung.<br />

Han-pu-ri and <strong>the</strong> Subjective-Objective Approach<br />

New types of <strong>the</strong>ology have emerged from <strong>the</strong> third world in response<br />

to <strong>the</strong> oppressed situations of <strong>the</strong> poor in <strong>the</strong>ir contexts in <strong>the</strong> late<br />

1960s. Before entering into a <strong>the</strong>ological conversation with my context,<br />

I want to review what <strong>the</strong>ological methodologies have been developed<br />

in my context before adapting some of those methodologies. I<br />

will also focus on <strong>the</strong> matters of women as “<strong>the</strong> doubly oppressed and<br />

marginalized among <strong>the</strong> poor.” 1 In order to find <strong>the</strong> least of our sisters<br />

in <strong>the</strong> place and time I am living in, I will follow <strong>the</strong> traces of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

oppressed lives in our society with a hermeneutics of empathy. I will<br />

start this search not from ancient time but from <strong>the</strong> time onwards that<br />

was under <strong>the</strong> strong patriarchal system, which still today has negative<br />

impacts on women’s lives.<br />

1. Methodologies of Third World Theologies<br />

I will explore what <strong>the</strong>ological methodologies have been applied to<br />

aim for <strong>the</strong> liberation of <strong>the</strong> oppressed in third world <strong>the</strong>ology. First, I<br />

examine han-pu-ri and social biography which have been evolved in<br />

<strong>the</strong> South Korean context and <strong>the</strong>n some o<strong>the</strong>r methodologies<br />

emerged from <strong>the</strong> third world will be also introduced. 2<br />

1<br />

See above chapter 1.<br />

2<br />

“[T]he ‘First World’ referred to <strong>the</strong> powerful, capitalist nations, mostly of <strong>the</strong> West; <strong>the</strong><br />

‘Second’ to <strong>the</strong> socialist countries of <strong>the</strong> East; and <strong>the</strong> ‘Third’ to <strong>the</strong> non-aligned ‘underdeveloped’<br />

and ‘developing’ countries in <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> world. Currently ‘Third World’ is used as a<br />

self-designation of peoples who have been excluded from power and <strong>the</strong> authority to shape<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir own lives and destiny. As such it has a supra-geographic denotation, describing a social<br />

condition marked by social, political, religious, and cultural oppressions that render people<br />

powerless and expendable. Thus Third World also encompasses those people in <strong>the</strong> First

38 Chapter 2<br />

Social Scientific Methodologies in Theology<br />

Suh Nam-Dong proposed <strong>the</strong> new hermeneutical framework of socioeconomic<br />

history and <strong>the</strong> sociology of literature in minjung <strong>the</strong>ology.<br />

Suh was convinced that this hermeneutical framework, which is<br />

adapted by political <strong>the</strong>ology, could overcome <strong>the</strong> limitations of <strong>the</strong><br />

traditional dogmatic and existentialist <strong>the</strong>ology, having little concern<br />

for <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> present time. 3 Especially, he explained that <strong>the</strong><br />

research of <strong>the</strong> socio-economic history of Korea enables <strong>the</strong>ologians<br />

to understand <strong>the</strong> reality of <strong>the</strong> minjung objectively. 4 Suh introduced<br />

Asian <strong>the</strong>ology, as it has been developed by <strong>the</strong> prominent Taiwanese<br />

<strong>the</strong>ologian, C. S. Song. Suh praised Song for his <strong>the</strong>ological ability<br />

and accomplishments, especially of inculturation <strong>the</strong>ology, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

of transposition as it was called by Song. 5 Yet Suh also pointed out<br />

its lack of <strong>the</strong> sociological perspective. 6 Suh saw him struggling with<br />

cultural <strong>the</strong>ological ideas concerning <strong>the</strong> supra-structure ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

with structural sin of political and economic institutions concerning<br />

<strong>the</strong> infra-structure. 7 Suh also wrote about <strong>the</strong> sociology of poverty and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ology of poverty and he used case studies, statistics and <strong>the</strong>ories in<br />

sociological research and introduced international declarations and<br />

regulations related to <strong>the</strong> human rights in order to analyze <strong>the</strong> social<br />

problem of poverty. 8 Suh recognized <strong>the</strong> need of liberation <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

alongside inculturation <strong>the</strong>ology in Asia. In Africa, Charles Nyamiti,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Tanzanian Roman Catholic <strong>the</strong>ologian also subdivides African<br />

<strong>the</strong>ology into two main schools of inculturation and liberation <strong>the</strong>ology.<br />

9<br />

The Indonesian woman <strong>the</strong>ologian, Marianne Katoppo wrote her<br />

small but innovative book, Compassionate and Free: An Asian Woman’s<br />

Theology in 1979 and she also includes <strong>the</strong> socio-political reali-<br />

World who form a dominated and marginalized minority. [...] Theological groups in <strong>the</strong> Third<br />

World, for example, EATWOT, affirm <strong>the</strong> term as valid and significant for <strong>the</strong>ir selfidentification,<br />

and maintain it for its <strong>the</strong>ological and evangelical relevance as an alternative<br />

voice.” Virginia Fabella, MM and R. S. Sugirtharaja (eds), Dictionary of Third World Theologies,<br />

New York 2000, 202f.<br />

3<br />

Suh, Historical References, 157f.<br />

4<br />

Op. cit., 167.<br />

5<br />

Suh Nam-dong, Cultural Theology, Political Theology and Minjung Theology, in: CTC<br />

Bulletin Vol.5. No.3 – Vol.6. No.1, 1984/1985, 12–15,12.<br />

6<br />

Suh Nam-Dong, 민중신학의 탐구 (The Study of Minjung Theology), Seoul 1983, 382.<br />

7<br />

Ibid.<br />

8<br />

Cf. Op. cit., 383–406.<br />

9<br />

Charles Nyamiti, African Christologies Today, in: Faces of Jesus in Africa, Robert J.<br />

Schreiter (ed.), Maryknoll, NY 1991, 3–23, 3.

The Female Face of Minjung 39<br />

ties of Asian women who are confronted with <strong>the</strong> various forms of<br />

oppression using statistics and case studies. 10 Ada María Isasi-Díaz,<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> pioneers of mujerista <strong>the</strong>ology analysed census and statistics<br />

in order to manifest <strong>the</strong> socioeconomic reality of <strong>the</strong> oppressed<br />

Hispanic women in U.S. society. 11 Besides, Isasi-Díaz took ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

step forward to provide a platform where <strong>the</strong> voices of grassroot Hispanic<br />

women can be heard in <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ological discourse and she<br />

adapted ethnomethodology, “a critique of professional social sciences<br />

that focuses on <strong>the</strong> particularities of <strong>the</strong> persons being investigated” in<br />

articulating mujerista <strong>the</strong>ology. 12 Therefore mujerista <strong>the</strong>ology uses<br />

<strong>the</strong> lived-experience of Hispanic women as <strong>the</strong> source of doing <strong>the</strong>ology.<br />

13 Isasi-Díaz has also made every effort to support grassroot Hispanic<br />

women as agents and subjects ra<strong>the</strong>r than to objectify <strong>the</strong>m by<br />

speaking about <strong>the</strong>m and for <strong>the</strong>m. 14 In <strong>the</strong> current global context,<br />

Peter C. Phan, a Vietnamese-American <strong>the</strong>ologian, also places emphasis<br />

on <strong>the</strong> experience of migration as source of intercultural <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

saying that “<strong>the</strong> existential predicament provides, as it were, a perspective<br />

for <strong>the</strong> elaboration of a <strong>the</strong>ology not merely about but out of<br />

<strong>the</strong> migration experience.” 15<br />

The Subjective-Objective Approach<br />

Theologians from <strong>the</strong> third world have reflected on <strong>the</strong> socio-political<br />

realities of <strong>the</strong> oppressed and <strong>the</strong>y have suggested <strong>the</strong> use of social<br />

scientific methodologies including <strong>the</strong> voice of <strong>the</strong> grassroots and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir lived experience. What methodologies can be used in <strong>the</strong> context<br />

of South Korea? Here two methodologies from <strong>the</strong> contextual <strong>the</strong>ologies<br />

in South Korea will be introduced and based on <strong>the</strong>m I will develop<br />

a complementary way of <strong>the</strong> subjective-objective approach.<br />

10<br />

Ursula King (ed.), Feminist Theology from <strong>the</strong> Third World: A Reader, Maryknoll, NY<br />

1994, 114; Cf. Marianne Katoppo, Compassionate and free: An Asian Woman’s Theology,<br />

Maryknoll, NY 1981.<br />

11<br />

Ada María Isasi-Díaz, En La Lucha/In <strong>the</strong> Struggle: Elaborating a Mujerista Theology,<br />

Minneapolis 2004, 39–43.<br />

12<br />

Op. cit., 80f.<br />

13<br />

Op. cit., 184.<br />

14<br />

Op. cit., 80f.<br />

15<br />

Peter C. Phan, The Experience of Migration as Source of Intercultural Theology, in: Contemporary<br />

Issues of Migration and Theology, Elaine Padilla and Peter C. Phan (eds), New<br />

York 2014, 179–209, 182.

40 Chapter 2<br />

(1) Han-pu-ri<br />

Suh Nam-Dong urges Christians (Churches) to become <strong>the</strong> priest of<br />

han who considers oneself as <strong>the</strong> medium of <strong>the</strong> voice of <strong>the</strong> voiceless<br />

by resolving and consoling han of <strong>the</strong> oppressed, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> priest<br />

of <strong>the</strong> atonement in western <strong>the</strong>ology, who considers oneself as <strong>the</strong><br />

medium of <strong>the</strong> atonement by making people feel guilty and forcing<br />

repentance. 16 Raymond Fung, <strong>the</strong> former secretary for Evangelism in<br />

<strong>the</strong> World Council of Churches’ Commission on World Mission and<br />

Evangelism stated that a person among <strong>the</strong> poor in <strong>the</strong> third world is<br />

not only a sinner, but also <strong>the</strong> sinned against. 17 His insight gives a<br />

fresh look at <strong>the</strong> oppressed people and how to look at <strong>the</strong> causes that<br />

make people oppressed. Jesus was called “a friend of sinners” (Mat<strong>the</strong>w<br />

11:19, Luke 7:34). 18 Fung urges us to rethink whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> people<br />

Jesus met can be seen only as sinners or not. Fung says that “men and<br />

women are not only willful violators of God’s laws, <strong>the</strong>y are also <strong>the</strong><br />

violated.” 19 The violated people should never be treated as sinners at<br />

one with <strong>the</strong> sins which must be destroyed, but <strong>the</strong> violated human<br />

dignity should be restored by removing <strong>the</strong> sins against <strong>the</strong>m. Minjung<br />

<strong>the</strong>ologians give <strong>the</strong> so-called sinners (but who are sinned against in<br />

reality) a Korean name, minjung of han. 20 The sinned against<br />

(minjung or victims) should be restored (or healed) in <strong>the</strong> image of<br />

God and <strong>the</strong> sins against people (which became han to <strong>the</strong> victims)<br />

should be removed.<br />

Chung Hyun Kyung paid careful attention to <strong>the</strong> role of a shaman<br />

as a priestess of han in <strong>the</strong> shamanistic ritual han-pu-ri from a feminist<br />

perspective. In <strong>the</strong> Korean history, women have been living painfully<br />

in <strong>the</strong> patriarchal society which has been supported by imported and<br />

institutionalized religions such as Confucianism, Buddhism and Christianity<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir “male-centered, power greedy and authoritarian”<br />

characteristics. 21 On <strong>the</strong> contrary, shamanism has been an indigenous<br />

religion to express <strong>the</strong> “living faith and daily struggles” of people and<br />

it has liberating elements for women in spite of its oppressive ele-<br />

16<br />

Suh, Study of Minjung Theology, Seoul 1984, 37–44.<br />

17<br />

Raymond Fung, Good News to <strong>the</strong> Poor – A Case for a Missionary Movement, in: Your<br />

Kingdom Come. Mission Perspectives, Report on <strong>the</strong> World Conference on Mission and<br />

Evangelism, Melbourne, Australia 12–25 May 1980, Geneva 1980, 83–93.<br />

18<br />

Cf. Wolfgang Stegemann and Luise Schottroff, Jesus and <strong>the</strong> Hope of <strong>the</strong> Poor, Maryknoll,<br />

NY 1986; Wolfgang Stegemann, The Gospel of <strong>the</strong> Poor, Minneapolis 1984.<br />

19<br />

Op. cit., 84. See above chapter 1.<br />

20<br />

Küster, Theology of Passion, 85.<br />

21<br />

Kwok Pui-lan, Introducing Asian Feminist Theology, Cleveland, Ohio 2000, 86.

The Female Face of Minjung 41<br />

ments as well. 22 If <strong>the</strong> liberating elements are to be given attention to,<br />

a shaman has been “a healer, comforter and counselor” for women by<br />

consoling <strong>the</strong> broken-hearted, healing <strong>the</strong> afflicted and restoring<br />

wholeness through communication with <strong>the</strong> spirits. 23 Thus, Kwok<br />

Pui-lan, a Hong Kong born postcolonial feminist <strong>the</strong>ologian introduces<br />

Jesus as <strong>the</strong> priest of han in <strong>the</strong> Korean context as <strong>the</strong> pluralistic<br />

and female image of Christ in her book Introducing Asian Feminist<br />

Theology. 24 This indigenous Christological image, <strong>the</strong> priest of han<br />

has been discovered through a dialogue with an ancient religion and<br />

culture in Korea.<br />

Buddhism and Christianity are <strong>the</strong> major religions in South Korea<br />

today. However, in ancient times, before <strong>the</strong> introduction of foreign<br />

religions, Shamanism was <strong>the</strong> religion of Koreans and <strong>the</strong>re were even<br />

official shamans who assisted <strong>the</strong> king while o<strong>the</strong>r shamans satisfied<br />

<strong>the</strong> people’s religious needs. When Buddhism and Confucianism were<br />

adopted by <strong>the</strong> successive dynasties of Shilla, Koryo and Chosun in<br />

Korea, Shamanism has declined and it has been despised and regarded<br />

as a religion fit for <strong>the</strong> ignorant in society. 25 When Confucianism was<br />

adopted as official religion in <strong>the</strong> Chosun dynasty, Korean women<br />

became inferior in status to men and became confined to <strong>the</strong>ir homes<br />

according to <strong>the</strong> patriarchal system of Confucianism. 26 In a family,<br />

women were subordinate to men <strong>the</strong>ir whole lives: to a fa<strong>the</strong>r before<br />

marriage, to a husband after marriage and to a son after a husband<br />

dies. 27 The gender roles of <strong>the</strong> patriarchal system confined women at<br />

home and <strong>the</strong> inside of <strong>the</strong> house became <strong>the</strong> limited sphere of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

activity while <strong>the</strong>ir husbands monopolized <strong>the</strong> public life outside of<br />

<strong>the</strong> house. Except for very limited cases, women could not set foot<br />

outside of a house. Women lost <strong>the</strong>ir power and <strong>the</strong>ir space in society.<br />

Shamanism and women have shared <strong>the</strong>ir lower social position and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir limited space in Korean history.<br />

22<br />

Ibid.<br />

23<br />

Op. cit., 88.<br />

24<br />

Ibid.<br />

25<br />

Cf. Volker Küster, Reflections on a woodcut by Hong Song-Dam, in: Exchange: Journal of<br />

Missiological and Ecumenical Research, vol. 26, no.1, Leiden May 1997, 159–171, 162.<br />

26<br />

Volker Küster refers to “<strong>the</strong> debate whe<strong>the</strong>r Confucianism is a religion or a philosophy in<br />

<strong>the</strong> study of religion” and explains that this debate comes from <strong>the</strong> emphasis of Confucianism<br />

on “an ethos oriented to creating harmony through a system of hierarchic relationships ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than a full-fledged religion”. He adds, however, that “ancestor veneration” shows a religious<br />

element of Confucianism, Küster, Theology of Passion, 34f.<br />

27<br />

For more detail, see below chapter 2.

Chapter 3<br />

The Emergence of Female Marriage Migrants in Korea.<br />

Contextual Transformations, New Subjects and<br />

Continuing Oppression<br />

Minjung <strong>the</strong>ology in South Korea has emerged and flourished regionally<br />

and internationally in <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 80s. The affectionate attention<br />

of its proponents went towards <strong>the</strong> oppressed and marginalized at<br />

that time and was even fur<strong>the</strong>r extended back into <strong>the</strong> history of Korea.<br />

Then, who is minjung in our times, in <strong>the</strong> 2000s and <strong>the</strong> 2010s? I<br />

will focus here on female marriage migrants as one kind of minjung in<br />

our times by applying <strong>the</strong> subjective-objective approach as a methodology,<br />

which was introduced in <strong>the</strong> previous chapter 2. It will enable<br />

me to listen to <strong>the</strong> voice of <strong>the</strong> voiceless, <strong>the</strong> marginalized and <strong>the</strong><br />

oppressed and name <strong>the</strong> oppressions <strong>the</strong>y experience in our context.<br />

1. Minjung in our Times?<br />

“Isn’t minjung <strong>the</strong>ology on <strong>the</strong> wane?” 1 In reply to <strong>the</strong> question raised<br />

by a Korean pastor, Jong-wha Park during an interview with a newspaper,<br />

Jürgen Moltmann, a German Reformed <strong>the</strong>ologian, answered: 2<br />

“The perspective of minjung <strong>the</strong>ology is still <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me of <strong>the</strong>ology.<br />

The term minjung <strong>the</strong>ology is not <strong>the</strong> issue, but <strong>the</strong> spirit which drives<br />

it should gain attention. I think that its concern for <strong>the</strong> poor and justice<br />

as <strong>the</strong> center of minjung <strong>the</strong>ology is still valid and will remain valid.”<br />

He added, “<strong>the</strong> approach of minjung <strong>the</strong>ology is all <strong>the</strong> more impera-<br />

1<br />

Part of this chapter has been published in Embarking on a Theological Journey with Literature<br />

– A Confluence of Two Stories of Migrant Brides, in: Minjung Theology Today, Kwon<br />

and Küster (eds), 127–144.<br />

2<br />

Jürgen Moltmann, 몰트만 “민중신학의 정신은 아직도 유효” (Minjung <strong>the</strong>ology is Still Valid),<br />

Interview by his former PhD-student Rev. Jong-wha Park, Kukminilbo, Seoul, May 12, 2009,<br />

http://news.kmib.co.kr/article/view.asp?arcid=0921285760&code=23111111&sid1=chr&sid2<br />

=0001 (accessed on Aug. 20, 2014).

60 Chapter 3<br />

tive in <strong>the</strong> global financial crisis which is a consequence of neoliberalism”.<br />

Moltmann esteemed minjung <strong>the</strong>ology highly, in particular its<br />

affectionate spirit toward those who are languishing in poverty and are<br />

discriminated against unjustly, which is in accordance with <strong>the</strong> concern<br />

of Jesus Christ in his life on earth.<br />

The term minjung was a very familiar word to those who lived in<br />

South Korean society in <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 80s. It was used for describing<br />

a human rights movement in a political struggle and a certain<br />

protestant <strong>the</strong>ology in pursuit of <strong>the</strong>ological reflections on those secular<br />

realities. However, this term does not seem to fit well any longer to<br />

those who live in <strong>the</strong> 2000s and 2010s, breaking away from <strong>the</strong> period<br />

of disgrace and darkness in <strong>the</strong> past and just entering into <strong>the</strong> period of<br />

justice and transparency, although we have not yet achieved this entirely.<br />

It is not an issue only for minjung <strong>the</strong>ologians to solve in <strong>the</strong><br />

post-developmental dictatorship era. Liberation <strong>the</strong>ology in Latin<br />

America is also in <strong>the</strong> same boat and suspicions are cast upon <strong>the</strong> relevance<br />

of liberation <strong>the</strong>ology in our postmodern society with its outdated<br />

social analytical tools. On <strong>the</strong> contrary, Kwok Pui-lan claims<br />

that “<strong>the</strong> challenge will be how <strong>the</strong> option for <strong>the</strong> margin will engage<br />

postmodernity in new ways and generate new insights for <strong>the</strong>ological,<br />

social, political, and economic thinking.” 3 While we are puzzled with<br />

<strong>the</strong> usage of this so-called outdated term, Ryoo Jang-Hyun, a South<br />

Korean <strong>the</strong>ologian, opines that it is still applicable. According to him,<br />

minjung has appeared to us in different faces in <strong>the</strong> 2000s and 2010s.<br />

He defines migrant workers, foreign brides, and foreign female sex<br />

workers as “wander-minjung” in <strong>the</strong> South Korean context, which is<br />

rapidly changing into a multicultural society. 4 These newly appeared<br />

minjung have gained an additional name, “wander” as a compound<br />

word, which is suggestive of a stranger who cannot return home to her<br />

or his homeland, and who has not yet become settled where she or he<br />

is living at present as her or his new home. This reminds me of a<br />

plant, which was originally uprooted from its homeland but could not<br />

put down roots in <strong>the</strong> ground and can only be potted in a foreign country.<br />

5<br />

3<br />

Kwok Pui-lan, Postcolonial Imagination & Feminist Theology, London 2005, 19f.<br />

4<br />

Jang-Hyun Ryoo, 다문화사회의 떠돌이 민중에 대한 신학적 이해 (A Theological Study of Wander<br />

Minjung in Multicultural Society), in: Theological Thoughts, vol.148, spring 2010, 41–64,<br />

44f. With reference to Gerd Theissen and Ahn Byung-Mu; Cf. Volker Küster, 마가복음의<br />

예수와 민중 (Jesus and Minjung in Mark), Trans. Myung-Su Kim, Seoul 2006, 93.<br />

5<br />

Korean immigrants in <strong>the</strong> United States share this wander experience. Jung Young Lee in<br />

<strong>the</strong> parable of <strong>the</strong> dandelion portrays an Asian American in <strong>the</strong> United States as a yellow

The Emergence of Female Marriage Migrants in Korea 61<br />

Table 2. The Number of International Marriages<br />

in South Korea, 1990~2008 6<br />

Year<br />

International<br />

Foreign<br />

Foreign<br />

Total<br />

Marriages<br />

Wives<br />

Husbands<br />

Marriages<br />

Number % Number % Number %<br />

1990 399,312 4,710 1.2 619 0.2 4,091 1.0<br />

1991 416,872 5,012 1.2 663 0.2 4,349 1.0<br />

1992 419,774 5,534 1.3 2,057 0.5 3,477 0.8<br />

1993 402,593 6,545 1.6 3,109 0.8 3,436 0.9<br />

1994 393,121 6,616 1.7 3,072 0.8 3,544 0.9<br />

1995 398,484 13,494 3.4 10,365 2.6 3,129 0.8<br />

1996 434,911 15,946 3.7 12,647 2.9 3,299 0.8<br />

1997 388,591 12,448 3.2 9,266 2.4 3,182 0.8<br />

1998 375,616 12,188 3.2 8,054 2.1 4,134 1.1<br />

1999 362,673 10,570 2.9 5,775 1.6 4,795 1.3<br />

2000 332,090 11,605 3.5 6,945 2.1 4,660 1.4<br />

2001 318,407 14,523 4.6 9,684 3.0 4,839 1.5<br />

2002 304,877 15,202 5.0 10,698 3.5 4,504 1.5<br />

2003 302,503 24,776 8.2 18,751 6.2 6,025 2.0<br />

2004 308,598 34,640 11.2 25,105 8.1 9,535 3.1<br />

2005 314,304 42,356 13.5 30,719 9.8 11,637 3.7<br />

2006 330,634 38,759 11.7 29,665 9.0 9,094 2.8<br />

2007 343,559 37,560 10.9 28,580 8.3 8,980 2.6<br />

2008 327,715 36,204 11.0 28,163 8.6 8,041 2.5<br />

1990~<br />

2008<br />

6,874,634 348,688 5.1 243,937 3.5 104,751 1.5<br />

Material: The National Statistical Office of Korea, Annual Report on Live Births and Deaths Statistics<br />

(based on vital registration)<br />

Korean Christian women engaged in <strong>the</strong> feminist movements have<br />

also detected women workers, comfort women and female marriage<br />

migrants as <strong>the</strong> new faces of female minjung since <strong>the</strong> 1970s. 7 Since<br />

1990s, female marriage migrants have become <strong>the</strong> new face of<br />

minjung, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y are wander, or female minjung. Ryoo introducflower<br />

in <strong>the</strong> green lawn. In his parable, dandelions are considered to be weeds and get used<br />

to be uprooted by lawn owners but, at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> story <strong>the</strong>y are kept in a plastic cup and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir seeds are blown off all over <strong>the</strong> rich green yards by <strong>the</strong> author. This story gives <strong>the</strong> hope<br />

of settlement to immigrants. Jung Young Lee, Marginality: The Key to Multicultural Theology,<br />

Minneapolis 1995, 10–13; Peter C. Phan, Jesus <strong>the</strong> Christ with an Asian Face, in Theological<br />

Studies 57, 1996, 399–430, 414.<br />

6<br />

Seol Dong-Hoon et al. (eds), 다문화가족의 중장기 전망 및 대책연구: 다문화가족의 장래인구추계<br />

및 사회·경제적 효과분석을 중심으로 (A Study of <strong>the</strong> Medium- to Long-term Prospects and<br />

Measures of <strong>the</strong> Multicultural Family in Korea: On <strong>the</strong> Focus of <strong>the</strong> Population Projection of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Multicultural Family in Korea, and <strong>the</strong> Analysis of its Socio-Economic Impacts on Korean<br />

Society), Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Seoul: 2009, 8. The National Statistical<br />

Office of Korea (NSO) was renamed as Statistics Korea (KOSTAT) on July 6, 2009.<br />

7<br />

See Chapter 7 for more detailed information.

62 Chapter 3<br />

es us to some of <strong>the</strong>ir agony as follows: <strong>the</strong>y suffer from domestic<br />

violence and abuse by <strong>the</strong>ir spouses or <strong>the</strong>ir family-in-laws, and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are economically dependent on <strong>the</strong>ir spouses. They are forced “to<br />

work at home, on a farm or at a factory”, and “to take care of <strong>the</strong> elderly,<br />

<strong>the</strong> sick or step children” at home. Sometimes, <strong>the</strong> international<br />

marriages are chosen by South Korean men with “<strong>the</strong>ir desire to beget<br />

children”. Divorce as <strong>the</strong> result of an abusive marriage cannot be a<br />

solution for female marriage migrants, because <strong>the</strong>y will not be able to<br />

see <strong>the</strong>ir children any more or <strong>the</strong>y will be deported as illegal immigrants.<br />

Beyond that, even children of those international couples are<br />

under conflict from “<strong>the</strong> disparity between two cultures, child abuse,<br />

racial prejudice and education problems”. 8<br />

A study on <strong>the</strong> oppression against female marriage migrants will<br />

be conducted in this chapter based on <strong>the</strong> subjective-objective approach<br />

as discussed in <strong>the</strong> previous chapter. Thereby <strong>the</strong> first two<br />

steps of han-pu-ri will be conducted in this chapter. The voice of <strong>the</strong><br />

voiceless based on <strong>the</strong> social analysis allows <strong>the</strong> oppressed to speak<br />

and to be heard and <strong>the</strong>ir oppressions to be named in this chapter. The<br />

last step, changing will be proceeded in chapter 7, after <strong>the</strong> continuation<br />

of <strong>the</strong> naming based on an aes<strong>the</strong>tic approach in chapter 4 and 5,<br />

and a <strong>the</strong>ological reflection in chapter 6.<br />

2. The Increase of Female Marriage Migrants<br />

In 2008, 36,204 South Korean people married foreigners, more than<br />

double <strong>the</strong> 15,202 in 2002 (see Table 2 above). International marriages<br />

are 11.0 percent of <strong>the</strong> total marriages in South Korea. It means that<br />

over one in ten newly-wed South Koreans have married a foreign<br />

spouse since 2004. The number of marriages between a foreign wife<br />

and a South Korean husband (8.6%) are three times higher than between<br />

a South Korean wife and a foreign husband (2.5%) of <strong>the</strong> total<br />

international marriages (11.0%). Among foreign spouses of <strong>the</strong> international<br />

marriages (36,204), 78 percent are women (28,163) in 2008.<br />

Increased international marriage can be explained by <strong>the</strong> “marriage<br />

squeeze”, which is caused by “<strong>the</strong> shortage of potential brides<br />

because of a low birth rate” and “single farmers who are under stronger<br />

pressure than anyone with poor conditions may go abroad to look<br />

for <strong>the</strong>ir brides”. 9 However, <strong>the</strong> majority of South Koreans live in <strong>the</strong><br />

8<br />

Ryoo, Theological Thoughts, 47- 50.<br />

9<br />

Seol, Prospects and Measures, 9.

The Emergence of Female Marriage Migrants in Korea 63<br />

city and many female marriage migrants live in <strong>the</strong> city as well with<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir spouses who are <strong>the</strong> urban poor. 10<br />

Table 3. The Number of International Marriages between Korean Husband<br />

and Foreign wife by Nationality in South Korea, 2006~2016 11<br />

Year<br />

Korean<br />

Husband<br />

&<br />

Foreign<br />

Wife<br />

Viet<br />

-nam<br />

China<br />

Philipp<br />

-ines<br />

Japan<br />

USA<br />

(Unit: case, %)<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

2006 29,665 10,128 14,566 1,117 1,045 271 331 394 1,813<br />

2007 28,580 6,610 14,484 1,497 1,206 524 376 1,804 2,079<br />

2008 28,163 8,282 13,203 1,857 1,162 633 344 659 2,023<br />

2009 25,142 7,249 11,364 1,643 1,140 496 416 851 1,983<br />

2010 26,274 9,623 9,623 1,906 1,193 438 428 1,205 1,858<br />

2011 22,265 7,636 7,549 2,072 1,124 354 507 961 2,062<br />

2012 20,637 6,586 7,036 2,216 1,309 323 526 525 2,116<br />

2013 18,307 5,770 6,058 1,692 1,218 291 637 735 1,906<br />

2014 16,152 4,743 5,485 1,130 1,345 439 636 564 1,810<br />

2015 14,677 4,651 4,545 1,006 1,030 543 577 524 1,801<br />

2016 14,822 5,377 4,198 864 838 720 570 466 1,789<br />

Thailand<br />

Cambodia<br />

Component<br />

Ratio<br />

Year-onyear<br />

Growth<br />

Rate<br />

100.0 36.3 28.3 5.8 5.7 4.9 3.8 3.1 12.1<br />

1.0 15.6 -7.6 -14.1 -18.6 32.6 -1.2 -11.1 -0.7<br />

According to statistics between 2000 and 2008 from <strong>the</strong> National Statistical<br />

Office of Korea, female marriage migrants mainly come from<br />

China, Vietnam, <strong>the</strong> Philippines, Japan, Cambodia, Thailand, Mongolia,<br />

Uzbekistan and o<strong>the</strong>r countries. 12 Chinese brides accounted for <strong>the</strong><br />

lion’s share with 46.9 percent, followed by Vietnam with 29.4 percent,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Philippines with 6.6 percent, Japan with 4.1 percent, Cambodia<br />

with 2.3 percent, Thailand with 2.2 percent, Mongolia with 1.8 percent,<br />

and Uzbekistan down to 1.7 percent in 2008. 13 However, <strong>the</strong><br />

new statistics released in 2017 show substantial changes and Vietnamese<br />

brides as <strong>the</strong> foreign spouses for South Korean men became<br />

<strong>the</strong> largest group with 36.3% percent, followed by China with 28.3<br />

10<br />

Ibid.<br />

11<br />

Statistics Korea (KOSTAT, formerly <strong>the</strong> Korea National Statistical Office), 혼인이혼통계<br />

2016 (Marriage and Divorce Statistics 2016), 15, http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/index.action<br />

(accessed on Nov. 10, 2017).<br />

12<br />

Seol et al., Prospects and Measures, 11.<br />

13<br />

Ibid.