NCC Magazine, Summer 2023

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

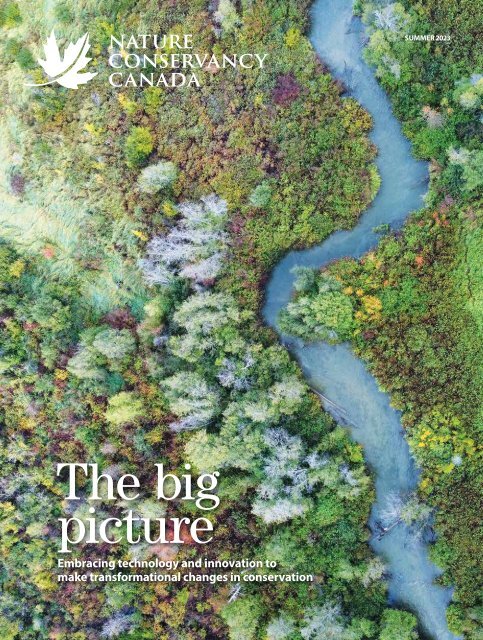

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

The big<br />

picture<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

Embracing technology and innovation to<br />

make transformational changes in conservation<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER 2021 1

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

4 Fragile beauty<br />

At-risk plant species of Canada’s<br />

Prairie grasslands.<br />

6 Nebo<br />

Spectacular landscapes abound<br />

where the boreal forest meets the<br />

Prairie grasslands in Saskatchewan.<br />

7 Big Backyard<br />

BioBlitz<br />

Connect with nature, and with<br />

each other.<br />

7 Nature’s lure<br />

Fishing, and the call of the water,<br />

is a constant draw for Kimberly Orren,<br />

executive director of Fishing for Success.<br />

12 Native grassland<br />

specialist<br />

Sprague’s pipit, an indicator of<br />

prairie health.<br />

14 A way with words<br />

Jane Gilbert, <strong>NCC</strong>’s chief storyteller,<br />

empowers nature’s heroes.<br />

16 Project updates<br />

IPCA collaboration, NB; Haley Lake Nature<br />

Reserve, NS; Reginald Hill Conservation<br />

Area, BC; tackling phragmites, QC.<br />

18 Dancing in the dark<br />

Esme Batten on chasing the aurora<br />

borealis with her camera.<br />

8 At the forefront<br />

Innovation and bold thinking are helping<br />

accelerate conservation.<br />

Digital extras<br />

Check out our online magazine page with<br />

additional content to supplement this issue,<br />

at nccmagazine.ca.<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410 | Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 3J1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca | Phone: 416.932.3202 | Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is the country’s unifying force for nature. We seek<br />

solutions to the twin crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate change through large-scale,<br />

permanent land conservation. <strong>NCC</strong> is a registered charity. With nature, we build a thriving world.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible for any calculations on<br />

saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed in Canada with vegetable-based inks by Warrens Waterless Printing.<br />

This publication saved 27 trees and 24,924 litres of water*.<br />

CREATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM. PHOTO: SEAN FEAGAN/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF. COVER: GATES CREEK, BC: ALEX NEWALL.<br />

*<br />

2 FALL 2022 natureconservancy.ca

Sharp-tailed grouse<br />

on The Yarrow, AB.<br />

Featured<br />

Contributors<br />

CHRISTIAN BLAIS.<br />

Dear friends,<br />

In my work for the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

in Quebec, I’m often struck by how the biggest successes<br />

come from the most unlikely places. Take our collaboration<br />

with Groupements forestiers Québec (GFQ), for instance. Five<br />

years ago, I couldn’t have imagined how <strong>NCC</strong> could work successfully<br />

with landowners whose primary activities included timber<br />

harvesting. But we decided to think outside the box, and we<br />

launched the Quebec Ecological Corridors Initiative, which brings<br />

together landowners and countless other partners to conserve<br />

natural areas that are connected by ecological corridors. Five<br />

years later, along with GFQ, we’ve developed a conference and<br />

training program that encourages more than 600 woodlot owners<br />

to foster ecological connectivity on their land.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s belief in the importance of embracing new ideas and<br />

innovation to help accelerate the pace of conservation showcases<br />

how, if we are to truly address the dual crises of biodiversity loss<br />

and climate change, we must go beyond our areas of expertise,<br />

work with new partners and collaborators and develop or embrace<br />

new tools. In this issue of the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong>, writer Jimmy Thomson explores three <strong>NCC</strong> projects<br />

that are doing just that.<br />

This issue illustrates how thinking big also means being ambitious:<br />

daring to try new things, working at larger scales and at<br />

a faster pace than ever before to conserve diverse, high-quality<br />

areas. Other times, like in the case of Reginald Hill in BC (Project<br />

Updates, page 17), it can also mean embracing big opportunities<br />

in the smallest area.<br />

By working together, we can all appreciate our role in building<br />

a thriving natural world. Because when nature thrives, we all thrive.<br />

Yours in conservation,<br />

Kateri Monticone<br />

Kateri Monticone<br />

Director of strategic conservation and innovation – Quebec<br />

Jimmy Thomson<br />

is a nationally recognized<br />

environmental<br />

journalist whose work<br />

has been published in<br />

The Narwhal, the Globe<br />

and Mail, The Walrus and<br />

others, and he has<br />

taught journalism and<br />

writing at UBC and UVic.<br />

He lives in Victoria, BC.<br />

He wrote “At the<br />

forefront,” page 8.<br />

Remie Geoffroi<br />

is an Ottawa-based<br />

illustrator. His clients<br />

include MIT, Wall<br />

Street Journal,<br />

Billboard and ESPN.<br />

He has illustrated<br />

titles from Martha<br />

Stewart and Tim<br />

Feriss. He enjoys<br />

travel, yoga and sport<br />

fishing. He illustrated<br />

“At the forefront,”<br />

page 8.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

Fragile beauty<br />

The richness and diversity of some of Canada’s prairie plant<br />

species are at risk<br />

If variety is the spice of life, then grasslands are like a chef’s palette. Canada’s Prairie<br />

grasslands are home to dozens of species at risk. Iconic wildlife like burrowing owl,<br />

greater sage-grouse and swift fox are found here, as well as several fascinating and<br />

beautiful at-risk plant species.<br />

Grassland areas themselves are diverse. Sand dunes, badlands and wetlands intersperse<br />

areas of grassy habitats, and each creates its own micro habitat. They also contain hundreds of<br />

types of plant species, including mosses, herbaceous plants and shrubs. These species epitomize<br />

the incredible variety of plant life found across the Canadian Prairies — from the fescue<br />

grasslands of Alberta’s foothills, to the tall grass prairie of Manitoba and the mixed-grass prairies<br />

in between. Sometimes this diversity is obvious — like when the flowering lupines, balsamroots<br />

and paintbrush cover the foothills in purple, yellow and red. At other times, it takes a hand<br />

lens and a discerning eye to appreciate.<br />

Whether common or rare, these plants benefit both people and ecosystems. Many flowering<br />

plants support pollinators, while others fertilize the soil by converting nitrogen in the air to<br />

forms that are usable by other species.<br />

Despite their importance, some of these grassland plants are now at risk. Some are naturally<br />

rare or have a limited range in Canada. Others are dwindling as more and more Prairie grasslands<br />

are lost or invaded by exotic species.<br />

The following are some of the at-risk plant species that you are helping protect by conserving<br />

Canada’s Prairie grasslands. The plants thank you, and so do we.1<br />

Western prairie<br />

white-fringed orchid<br />

When you hear the word orchid,<br />

you can’t help but picture something<br />

stunning, and the western prairie<br />

white-fringed orchid is no exception.<br />

This gorgeous, white-flowered<br />

plant found in Manitoba’s tall grass<br />

prairie grows in wet, calcium-rich<br />

prairies and meadows. Manitoba’s<br />

population of this endangered<br />

species, which includes half of its<br />

global population, is the northernmost<br />

of its range. A perennial species,<br />

western prairie white-fringed orchid<br />

can reach heights of 40 to 90 centimetres,<br />

and attains peak bloom from<br />

late June to mid-July.<br />

LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF. ILLUSTRATIONS: JACQUI OAKLEY.<br />

4 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Tiny Cryptantha<br />

Found in river valleys in southeastern<br />

Alberta and southwestern Saskatchewan,<br />

this small, hairy plant has tiny<br />

white flowers with yellow centres.<br />

Canadian populations of this threatened<br />

species, which is also known as<br />

little cat’s-eye, are separate from the<br />

rest of its population, with the closest<br />

being about 200 kilometres to the<br />

south in Montana. Found in sandy<br />

upland areas and sand dunes, tiny<br />

Cryptantha is threatened by habitat<br />

loss and degradation.<br />

Western blue flag<br />

A native iris, western blue flag is a<br />

federal species of special concern found<br />

in Alberta. Its sword-shaped leaves<br />

produce stalks with two to four pale- to<br />

deep-blue flowers. It most commonly<br />

grows in the transition area between<br />

grassland and streamside habitat. A<br />

primary threat facing western blue flag<br />

is competition from invasive species.<br />

Western spiderwort<br />

This threatened plant is found on<br />

sand dune ridges, typically those<br />

that are steeper and south-facing. It<br />

has been observed at a handful of<br />

sites in southeastern Alberta, southern<br />

Saskatchewan and southwestern<br />

Manitoba. Blink and you might miss it;<br />

western spiderwort blooms from May<br />

to July, with each of its eye-catching<br />

purple-blue flowers lasting for only<br />

a single day. This plant is pollinated<br />

mainly by sweat bees.<br />

Small white<br />

lady’s-slipper<br />

Found in the tall grass and mixed-grass<br />

prairie of Manitoba, small white lady’s-slipper<br />

generally lives in areas affected by<br />

natural disturbances, such as wildfires, light<br />

grazing and mowing. Without these<br />

disturbances, tall vegetation and woody<br />

plants will outcompete these tiny orchids.<br />

Small white lady’s-slipper is named, aptly,<br />

after its slipper-shaped flower, which blooms<br />

from May through June.<br />

Hare-footed locoweed<br />

A threatened member of the pea family,<br />

hare-footed locoweed is found in the fescue<br />

grasslands of southern Alberta. The first<br />

part of this species’ name refers to the fuzzy<br />

outer part of the flower, which some think<br />

looks like a rabbit’s foot. This low-growing,<br />

purple-flowered plant is being threatened by<br />

habitat loss and competition from invasive<br />

species, particularly crested wheatgrass.<br />

Soapweed<br />

Also widely known by its genus name,<br />

yucca, this threatened plant is found on<br />

coulee slopes in southern Alberta and<br />

Saskatchewan. It has stiff, pointed leaves<br />

and a group of creamy-white flowers that<br />

emerge from a flower stalk that grows up<br />

to 100 centimetres tall. Soapweed supports<br />

several specialized moth species, which<br />

are endangered in Canada.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

Township Road 500<br />

<br />

N<br />

Ordale Road<br />

Nebo<br />

Nebo<br />

Spectacular landscapes abound in Saskatchewan,<br />

where the boreal forest meets the Prairie grasslands<br />

Worries fade as you explore the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s)<br />

Nebo property, located approximately 70 kilometres from Prince Albert,<br />

Saskatchewan. The geography here is spectacular, with rolling hills<br />

ending in secluded forest-fringed wetlands. As you hike along a remarkable transition<br />

zone that bridges boreal forest with Prairie grasslands, you may come across<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s forest restoration work that began on-site in 2017; more than 32,000 white<br />

spruce seedlings have been planted with the generous support of Tree Canada.<br />

As you look over the hills, you may spot wildlife such as deer, moose, songbirds and<br />

many waterfowl.1<br />

LEARN MORE<br />

natureconservancy.ca/nebo<br />

LEGEND<br />

-- Railbed Trail<br />

-- Cutblock Trail<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• American badger<br />

• American black bear<br />

• barn swallow<br />

• black-and-white warbler<br />

• boreal chickadee<br />

• Canada jay<br />

• Canada warbler<br />

• common nighthawk<br />

• great crested flycatcher<br />

-- West Trail Connection<br />

-- East Trail Connection<br />

• green-winged teal<br />

• hooded merganser<br />

• horned grebe<br />

• moose<br />

• northern long-eared bat<br />

• olive-sided flycatcher<br />

• rusty blackbird<br />

• western grebe<br />

• yellow-headed blackbird<br />

MAP: JACQUES PERRAULT. PHOTOS L TO R: MIKE DEMBECK; MIKE DEMBECK; MIKE DEMBECK; MIKE DEMBECK; LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

6 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

ACTIVITY<br />

CORNER<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

L TO R: BRIANNA ROYE; EMILY WILLIAMS.<br />

Big Backyard<br />

BioBlitz<br />

Connect with nature, and with<br />

each other<br />

Bioblitzes are community science efforts to<br />

document as many species as possible within<br />

a specific area and time period, using your smartphone<br />

or tablet. The Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) Big Backyard BioBlitz is a five-day,<br />

go-at-your-own-pace event to document the<br />

creatures around us. The bonus is that your<br />

observations can help conservation experts take<br />

stock of local biodiversity, track rare species and<br />

tackle invasive ones. Here are four ways to make<br />

it fun for all:<br />

FAMILIES<br />

Make it a scavenger hunt for kids and adults,<br />

and team up to see who can spot the largest<br />

number of critters.<br />

FRIENDS<br />

Because the BioBlitz is done using your phone and<br />

then uploaded to a global database, it doesn’t<br />

matter whether your friends are near or far. Make<br />

a game of it and challenge them to see who can<br />

submit the most species observations.<br />

NATURE LOVERS<br />

Learn a handful of fun facts about a plant, animal<br />

or insect you’ve observed, so you can share them<br />

with other nature lovers.<br />

NEXT-LEVEL ENTHUSIASTS<br />

Capture the sounds of a bird or insect on your next<br />

walk. Notice the different sounds birds make in<br />

urban areas compared to more natural areas.<br />

Turn your gaze to nature over the August long<br />

weekend and join thousands of other nature lovers<br />

who’ll be contributing to valuable science data.<br />

Big Backyard BioBlitz: August 3–7<br />

Sign up to participate at backyardbioblitz.ca.<br />

Nature’s lure<br />

Kimberly Orren, executive director of Fishing for Success, is<br />

guided by the sounds and stories found at the ocean’s edge<br />

While I can’t bring a boat in my backpack, I would definitely want to make<br />

certain that my wanderings bring me to the water. Whether it is a stream<br />

or a pond, a lake or waterfall, or, as so often in my favourite places to<br />

hike in my province, to the ocean’s edge!<br />

We are fortunate in Petty Harbour-Maddox Cove to have the East Coast Trail,<br />

which runs along some of the most beautiful coastlines in Newfoundland and Labrador<br />

and passes through a Nature Conservancy of Canada property, part of the fog forest.<br />

This brings me to my favourite spot here: a magic tree! Sitting beneath it, you can<br />

hear the waves crashing below and tell stories about weather lore and how the sound<br />

of waves changes with the wind direction or intensity. Beneath the crashing, you<br />

might hear another rhythm of the swells that hint at tomorrow’s weather that is pushing<br />

just beyond the horizon.<br />

There are barriers to nature access, and they are multiplied when it comes to<br />

the ocean or learning traditional fishing skills. Fishing is part of the human experience;<br />

a shared heritage that predates agriculture. The experience of fishing is<br />

transformative. It is deeply personal and drives creative thought. Many scientists<br />

even cite an experience at the beach or a fishing trip with a parent as the moment<br />

that sparked their interest in the natural world.<br />

Every child should be provided with this activity as a building block to their<br />

education about the natural world. As land dwellers, we forget that we cling to less<br />

than 30 per cent of the Earth’s surface. Our very existence depends on the health of<br />

aquatic ecosystems. I urge you to plan a hike to any water’s edge, perhaps sit beneath<br />

your own magic tree, and listen to the water as it makes its way out to the ocean.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 7

At the<br />

forefront<br />

Using bold thinking, innovative approaches<br />

and new technologies to accelerate conservation<br />

BY Jimmy Thomson, journalist and journalism teacher<br />

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES.<br />

ILLUSTRATION: REMIE GEOFFROI.<br />

8 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

ALBERT LAW.<br />

The view from PKOLS;<br />

Aerin Jacob.<br />

The wind is pummelling the top of PKOLS as<br />

I reach the summit, trailing behind the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) science and research director, Aerin<br />

Jacob. It’s a rare day of extreme wind on the southern tip<br />

of Vancouver Island; a day when the ocean below seems bent on overtaking<br />

the shoreline, and the occasional drops of rain, even up here, taste<br />

every bit as salty as sea spray as the coastline’s discrete parts blend<br />

together in the maelstrom.<br />

The squat hill, also known as Mount Douglas but now increasingly<br />

recognized by its original name in the local SENĆOŦEN language, may<br />

feel like a high mountain peak on a day like this, but it’s only 225<br />

metres high. Still, this municipal park provides a stellar vantage point<br />

from which to see the blurry lines delineating the landscape below:<br />

farmland that bleeds into golf courses; leafy residential streets that disappear<br />

into parks; and in the middle distance, the dense tangle of the<br />

provincial capital, which itself falls off at jagged edges into the ocean.<br />

If this landscape was a mosaic made up of individual tiles, Jacob<br />

explains, each tile would have its own role to play in the region’s ecology.<br />

Here on PKOLS, a bald eagle makes use of the wind to ride a little<br />

higher above the bending Garry oaks. The oaks themselves are draped<br />

in lichens like tinsel — a sign of good air quality, I’m told — and further<br />

down the slope, grand old cedar and Douglas-fir trees shade moist soil<br />

and streams. It’s the very picture of an urban protected area.<br />

By contrast, it’s tempting to think of the farmland and residential<br />

areas on the plain below as sacrifice zones, less important to the goals<br />

of conservation — but that would be a flawed assumption that doesn’t<br />

encompass how nature works and what biodiversity and people need.<br />

“We know that the number and severity of threats facing nature and<br />

the pace of change are expanding rapidly. We have to learn from and<br />

expand on tried-and-true approaches, like securing and stewarding private<br />

land,” Jacob says. “We need to make transformational changes at<br />

landscape scales, changes that help nature and people, now and years<br />

from now. We need to think big and embrace innovation.”<br />

When unprecedented biodiversity decline and climate change are ripping<br />

at the interwoven fabric of ecosystems everywhere, Jacob argues, it’s<br />

not enough to do what we can and hope for the best. Big, ambitious goals,<br />

like <strong>NCC</strong>’s determination to double support in the next three years and<br />

double its impact by 2030, demand a bold approach — where no method<br />

is taken for granted, and neither successes nor failures go unanalyzed.<br />

New tools are needed: financial tools that attract private sector<br />

investment to conserve nature, next-generation technologies<br />

to make smarter use of data, and planning technology that<br />

tracks, understands and communicates changes on each<br />

of those little tiles spread out below us, but on a national<br />

scale. A bird’s-eye view can help shrug off modes of<br />

thinking that risk falling short of the transformative<br />

conservation outcomes that are needed.<br />

As an example, Jacob explains that she’s working on<br />

new ecological connectivity research that will evaluate<br />

the linkages between protected areas across Canada. The<br />

project will show how each protected area contributes to<br />

overall connectedness, and how the network as a whole<br />

can be enhanced by new conserved areas or restoration.<br />

“We have to speed up conservation and make it stronger.<br />

We need to get much better, more specific, at understanding<br />

what works, in which places, and for whom,” Jacob says. “And<br />

the best ways you can do that are to be open to new collaborations<br />

and ideas, try new things and test them to see if they're working<br />

as intended.”<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 9

Richard Schuster; Boreal Wildlands, ON.<br />

All of it — the bold thinking, the innovative<br />

approaches, the new technologies —<br />

needs to be brought to bear in the light of day<br />

so that people understand what’s happening<br />

to nature around them and why.<br />

Digital impact<br />

The point where conservation enters the<br />

digital era is Richard Schuster’s wheelhouse.<br />

Schuster is <strong>NCC</strong>’s director of spatial planning<br />

and innovation, having made the jump from<br />

academia after growing excited about the<br />

possibilities for putting his ideas into action.<br />

The Conservation Technology Project<br />

he’s heading up is working to create decision-support<br />

tools that can help governments<br />

and organizations make better-informed<br />

choices about how to use land.<br />

“We need to be more strategic about<br />

where we work and what we do,” he says.<br />

That means doing more with what we have<br />

— information and land, naturally, but also<br />

community buy-in. Good intentions and<br />

strong policy don’t amount to much when the<br />

policies are ultimately rejected by confused<br />

and upset stakeholders.<br />

Thanks to the project, real-time discussions<br />

can happen with actual data and analysis.<br />

Members of the public, landowners or partners<br />

can see what impact different decisions<br />

will have with the click of a mouse, rather<br />

than speaking in abstractions and goals. For<br />

example, if decision-makers want to know<br />

how climate change will affect a landscape,<br />

they can turn on that information in the tool,<br />

which allows users to predict the impacts of<br />

climate change on current or future conservation<br />

areas and the species that live in them.<br />

This helps identify conservation actions that<br />

can help mitigate these impacts.<br />

“The groundbreaking part to me is that our<br />

tools allow people to interact with complex<br />

conservation data, ideas and algorithms that<br />

are part of the tool in a straightforward way,<br />

and actually do it more or less live,” Schuster<br />

says. “Even three years ago, nobody in the<br />

world was able to do that.”<br />

That’s a revolutionary tool in a space<br />

where conversations can be limited by different<br />

levels of access to high-quality information<br />

or the ability to picture the likely<br />

outcomes of different decisions.<br />

When the public and decision-makers<br />

see the results of good conservation policy,<br />

that can help gain buy-in for a new round<br />

of beneficial policies — a feedback loop that<br />

makes it essential to be able to measure<br />

success and be able to communicate it in<br />

precise terms.<br />

That communication piece is something<br />

Schuster’s project can help with, too.<br />

Satellite-based observations can help <strong>NCC</strong><br />

and partners monitor sites (even remote<br />

ones) from a distance and understand<br />

changes over time as action is taken.<br />

“That makes it more practical to ‘visit’ each<br />

place every year,” Schuster explains. “If we<br />

implement a restoration activity, it will also<br />

help us track over time what kind of impact<br />

the activity has.”<br />

Some of that work can also be helped by<br />

harnessing people’s eagerness to understand<br />

nature — community science tools like<br />

iNaturalist and eBird are constantly adding to<br />

their databases with real-life observations,<br />

and Schuster’s team is using those open data<br />

sources to better predict where species can<br />

be found.<br />

ADAM BIALO/KONTAKT FILMS; PHOTO COURTESY RICHARD SCHUSTER. ILLUSTRATION: REMIE GEOFFROI.<br />

10 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

MIKE DEMBECK; PHOTO COURTESY ADAIR RIGNEY.<br />

Artificial intelligence (AI), perhaps the<br />

most revolutionary technology space of this<br />

era, has potential in conservation as well. Decision-making<br />

and monitoring programs benefit<br />

from “machine learning,” with first-of-theirkind<br />

AI systems making complex math tools<br />

more accessible to more users.<br />

“They can be used anywhere in Canada<br />

and use the best available information on<br />

biodiversity, nature's contributions to people<br />

and threats like climate change and human<br />

impacts. This will allow users to determine<br />

where to act and what to do to help nature<br />

thrive,” Schuster says. Because it’s all about<br />

creating opportunities to deploy better information<br />

to make better decisions, those tools<br />

are available not just to <strong>NCC</strong> staff but to anyone<br />

who wants to use them — from other<br />

land trusts and community organizations to<br />

all levels of government and landowners.<br />

But it can’t just be a matter of allowing<br />

algorithms to make those decisions for us.<br />

Joe Bennett, an associate professor at Carleton<br />

University who supervised Schuster’s<br />

postdoctoral fellowship before he made the<br />

jump to <strong>NCC</strong>, stresses that transparency in<br />

how the decisions are made is critical to<br />

achieving good results.<br />

“What happened in previous cases was<br />

somebody chooses a place, or a group of<br />

people choose a place, and nobody else really<br />

knows why,” he says. “Transparency is very,<br />

very important, and in the future will help to<br />

alleviate some conflict.”<br />

Transparency, Bennett said, may even<br />

mean going as far as sitting down with stakeholders,<br />

laptop open, and showing how<br />

outcomes change as different needs and values<br />

are weighted above others. That’s something<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s decision-making tools can do.<br />

Innovative funding<br />

Big, bold ideas don’t always cost money.<br />

Sometimes, they can be harnessed as a way<br />

of generating funding that can support the<br />

work that needs doing.<br />

Floods can cause billions of dollars in damage<br />

to cities and farmland, and we know that<br />

they’re made worse by the loss of wetlands.<br />

Governments, landowners and insurance<br />

companies all know what’s at risk.<br />

“Insurance companies are incredibly aware<br />

of the increasing costs that they are paying out<br />

in Canada for climate-related impacts,” says<br />

Adair Rigney, who is the director of projects<br />

and innovation for <strong>NCC</strong>’s Nature + Climate<br />

Projects Accelerator (the Accelerator) team.<br />

Conserving wetlands is one way to minimize<br />

those costs in the long term. There’s<br />

a growing recognition that the benefits of<br />

protecting nature accrue beyond satisfying<br />

our fondness for wild places and creatures:<br />

nature provides direct benefits to humans,<br />

with financial implications. And there is a tremendous<br />

amount of work going on right now<br />

to figure out how to measure those benefits<br />

and find ways to attract private-sector investment<br />

to support their conservation.<br />

“Protected areas are not just about<br />

nature for nature’s sake; they actually provide<br />

crucial benefits to people near and<br />

far,” Rigney says. The same thinking can<br />

apply to other nature-based solutions.<br />

“It’s about showing how our conservation<br />

projects provide nature-based services to<br />

society, and monetizing them.”<br />

Now <strong>NCC</strong> is trying something new for the<br />

organization: restoring forested areas in Manitoba<br />

by combining habitat restoration with<br />

carbon credit markets to attract more investment<br />

to its work. <strong>NCC</strong> is considering restoring<br />

degraded forests and planting new trees<br />

between Riding Mountain National Park and<br />

Duck Mountain Provincial Forest. These projects<br />

could generate carbon credits, which<br />

represent the amount of carbon dioxide that<br />

the trees will absorb from the atmosphere<br />

over their lifetime. The revenue generated<br />

from the sale of carbon credits can be used to<br />

support other conservation work, creating<br />

a positive feedback loop.<br />

“If this pilot project ends up being viable,<br />

and we proceed, there is a high potential this<br />

could be applied to other <strong>NCC</strong> lands requiring<br />

some reforestation efforts — to hopefully<br />

recoup some costs and/or attract interested<br />

partners or conservation-minded investors,”<br />

Rigney explains.<br />

It is an opportunity to try something big<br />

and important, and to learn from it.<br />

It doesn’t need to stop there. Think of the<br />

benefits that pollinators provide all of us when<br />

we protect their habitat, or how salt marshes<br />

protect coastlines from erosion: nature is our<br />

safety net, and any thought of replacing the<br />

benefits that people get from nature with engineered<br />

solutions sets the mind reeling at the<br />

cost alone. The Accelerator team is working to<br />

better understand the value of these services<br />

and attract investment in nature, so we don’t<br />

need expensive engineering solutions.<br />

Adair Rigney; Point Escuminac Nature Reserve, NB.<br />

Hearts and minds<br />

Jacob and I last only a few moments in the<br />

stiff bluster at the peak of PKOLS. We’re<br />

practically alone up there, maybe for good<br />

reason. On a calmer day, this hill would be<br />

swarming with nature lovers — young<br />

couples, active seniors, dog walkers, maybe<br />

even iNaturalist-wielding birders incidentally<br />

contributing to <strong>NCC</strong>’s data program — but<br />

today, most of our fellow Victorians have<br />

better sense than to venture up.<br />

Those people’s care for the world around<br />

them is critical for all of this work to succeed.<br />

Even with the growing recognition of nature’s<br />

financial importance, its intrinsic and<br />

emotional value retains its pull for most of us.<br />

When hard tradeoffs need to be made, with<br />

help from data analyzed by sophisticated<br />

computer models, the actual decisions still<br />

rest in human hands and the outcomes still<br />

rest on human shoulders.<br />

If <strong>NCC</strong> is to meet its ambitious goals, it<br />

will take both sides of that coin — hearts and<br />

minds — to fight the headwinds.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Sprague’s pipit<br />

This native grassland specialist is an indicator of landscape-scale prairie health<br />

GLENN BARTLEY.<br />

12 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

Finding Sprague’s pipits on the ground<br />

in their native prairie habitat is challenging.<br />

Both males and females of this medium-sized<br />

songbird have a slender bill and brownish tan feathers<br />

that aid with camouflage among soil and dried<br />

vegetation. However, during the breeding season, males<br />

announce their presence as they circle high above their<br />

territories while singing a series of cascading, twinkling<br />

notes. The song is paired with an aerial display that<br />

includes wing fluttering, a series of glides, and the<br />

flash of white outer tail feathers. The exhibitions<br />

often continue for 30 minutes or more and<br />

end with an impressive nose-dive held<br />

until just a few metres above<br />

the ground.<br />

RANGE<br />

This species can be found<br />

from southern and central<br />

Alberta to southwestern Manitoba,<br />

to southern Montana, northern South<br />

Dakota and northwestern Minnesota.<br />

In winter, Sprague’s pipits can be<br />

found in the central southern<br />

U.S. and northern Mexico.<br />

What <strong>NCC</strong> is doing<br />

to protect habitat for<br />

this species<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) owns and protects several<br />

properties where Sprague’s pipit<br />

has been found. In Manitoba, these<br />

include Fort Ellice, Maple Lake and<br />

the Yellow Quill Prairie Preserve.<br />

In Saskatchewan, this species has<br />

been observed on projects in the<br />

Missouri Coteau, Milk River basin, Upper<br />

Qu’Appelle, Saskatoon Prairie and<br />

Lower-Qu’Appelle-Assiniboine-Quill<br />

Lakes natural areas.<br />

In Alberta, Sprague’s pipit has been<br />

found on all of <strong>NCC</strong>’s grassland natural<br />

areas, including Haugan, Ridge and<br />

Sandstone ranches.<br />

Most of <strong>NCC</strong>’s projects supporting<br />

Sprague’s pipit are grazed by cattle or<br />

bison. Grazing is an important tool for<br />

managing grassland vegetation. Without<br />

grazing, the plants would become too<br />

tall and dense, excluding the species<br />

from otherwise usable habitat.1<br />

HABITAT<br />

These native grassland specialists<br />

breed in large, nearly treeless expanses<br />

of short- and mixed-grass prairie. During<br />

migration and while overwintering, Sprague’s<br />

pipits rely on open grassland areas, including<br />

pastures, haylands and agricultural fields.<br />

Because this species requires large blocks of<br />

intact native grasslands, it is a useful<br />

indicator of landscape-scale prairie<br />

health and connectivity.<br />

•<br />

Breeding range<br />

in Canada<br />

CALVIN FEHR.<br />

HELP OUT<br />

Help protect habitat for<br />

species at risk at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

donate.<br />

THREATS<br />

The Committee on the Status of<br />

Endangered Wildlife in Canada has<br />

assessed Sprague’s pipit as threatened. This<br />

species is threatened by the loss and fragmentation<br />

of its native prairie habitat throughout its<br />

breeding and winter range and pesticides, which<br />

can reduce insect prey densities. Within the species’<br />

breeding range, threats also include haying<br />

during the birds’ nesting period, overgrazing,<br />

increased nest predation, and intensified<br />

drought and wet periods caused by<br />

climate change.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 13

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

A way<br />

with<br />

words<br />

How <strong>NCC</strong>’s chief storyteller empowers nature’s heroes<br />

BRIANNA ROYE.<br />

14 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

While chasing stories across the country<br />

as a broadcast journalist, Jane Gilbert<br />

would watch from her airplane window<br />

as Canada unfurled below her like a patchwork quilt.<br />

She was awed by the colours, the tufts of forests<br />

abutting farm fields, the seams of dark blue rivers<br />

and grey roads stitching together each section.<br />

BRIANNA ROYE.<br />

But shortly into her role as the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>’s) chief storyteller, she was struck by a new and sobering<br />

thought: “I realized that’s what fragmentation looks like. In between<br />

those places below me, the species couldn’t communicate anymore.”<br />

She saw the need to bring those places and their stories back together.<br />

Since 2008, Gilbert has worked to connect <strong>NCC</strong> supporters, partners<br />

and the public with the stories of those natural places. Along<br />

the way, she has shifted <strong>NCC</strong>’s own narrative from one of earnestly<br />

thinking the need for conservation might one day diminish, to one of<br />

urgency and ambition, centring each story around the people who<br />

make nature conservation possible.<br />

And now, as she prepares to leave <strong>NCC</strong> for what she calls<br />

“rewirement,” Gilbert reflects on the challenge of turning the<br />

intimidating story of nature loss into one of hope and possibility.<br />

“It struck me that if people can’t see themselves in the picture,<br />

they can’t see the opportunity to be part of the solution,” Gilbert<br />

says of her early days with <strong>NCC</strong>. “The key to it all is the hero. If you<br />

don’t have a hero in the story, you don’t have a story.”<br />

Flip through the chapters of <strong>NCC</strong>’s own tale and you will find<br />

a swelling cast of characters today. “We have 500,000-plus heroes<br />

who work with us now,” she says, referring to <strong>NCC</strong>’s supporters.<br />

“And more joining every day. That’s in addition to our amazing staff.”<br />

It struck me that if people can’t see<br />

themselves in the picture, they can’t see<br />

the opportunity to be part of the solution.<br />

The key to it all is the hero. If you don’t<br />

have a hero, you don’t have a story.<br />

The bear tracks stamped into the mud of a trail, the muscle aches<br />

felt after a day of clearing invasive garlic mustard from a forest —<br />

“to our staff in the field, it is part of the everyday. To us [our team of<br />

storytellers], it is phenomenal,” Gilbert says. “And when we know<br />

about it, we can celebrate it.” That’s why Gilbert has spent 15 years<br />

repeating a trademark phrase, empowering <strong>NCC</strong> colleagues to find<br />

(and sometimes even be) the heroes in their own stories: “Your<br />

ordinary is everyone else’s extraordinary.”<br />

Gilbert’s own <strong>NCC</strong> life has been punctuated with trips to some of<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s most impressive vistas — the jagged coasts along the Atlantic,<br />

the aromatic sage-swept Prairies, the mountain tops in the Rockies.<br />

Closer to home, she has watched the power of nature unfold outside<br />

her office window each time a breeding pair of peregrine falcons<br />

(a conservation success story in their own<br />

right) raised their young outside her window.<br />

But she knows few people will be able to<br />

experience those moments first-hand.<br />

So instead, Gilbert has seamlessly brought<br />

humans and nature together in <strong>NCC</strong>’s story,<br />

encouraging everyone to see themselves<br />

as people who can make a difference — as<br />

heroes and as part of nature. <strong>NCC</strong>’s voice is<br />

stronger today as a result of her insight and<br />

guidance, which have shaped the stories we<br />

share, and the way we understand our connections<br />

to nature and conservation.<br />

“It’s really easy, sitting in our concrete<br />

canyons and urban centres, to lose sight of<br />

that, but we’re here because the rivers and<br />

the wetlands on the outskirts of our communities<br />

are providing the clean water for us to<br />

drink, and the forests are storing carbon and<br />

helping cool the climate,” Gilbert says.<br />

“Nature is us,” she says, be it the gardener<br />

she watches plant sunflowers on a balcony<br />

in the middle of Canada’s largest city or the<br />

volunteer pulling invasive plants at an <strong>NCC</strong><br />

nature reserve. By centring human heroes in<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s story, Gilbert has helped stitch together<br />

the fates of humans and nature, trying to<br />

mend the disparate patchwork quilt of a landscape<br />

she saw 15 years ago.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> 15

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> collaborates on IPCA<br />

SOUTHEAST NEW BRUNSWICK<br />

2<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

Protecting the Arch<br />

“My great-grandfather bought land on a lake north<br />

of Kingston, Ontario, in 1930. As I grew up in Montreal,<br />

I thought that that area was a relatively undiscovered<br />

gem; my friends had cottages in the Laurentians or<br />

Eastern Townships of Quebec, and people I knew in<br />

Toronto all headed to the Muskokas and places north.<br />

I soon learned that this special area in Ontario had<br />

a name: the Frontenac Arch.<br />

“My wife and I became aware of <strong>NCC</strong>’s activities in the<br />

Arch, and soon started contributing to its efforts to purchase<br />

strategic parcels of land. Today, <strong>NCC</strong> owns and manages<br />

over 2,760 hectares in the Arch and has assisted with<br />

the protection of an additional 2,985 hectares of habitat.<br />

“It’s interesting that the Arch has always been very popular<br />

with Americans, due to its proximity to the border and<br />

myriad of recreation activities. The Frontenac Arch is one<br />

of nature’s most important corridors between our two<br />

countries, connecting the Canadian Shield with the Appalachian<br />

Mountains. My wife and I are now dual citizens,<br />

domiciled in the USA, and I serve as chair to the board of<br />

American Friends of Canadian Nature, helping Americans<br />

support Canadian conservation through funding and<br />

land donations to <strong>NCC</strong> and other organizations.”<br />

~ Tim Gardiner has been an <strong>NCC</strong> donor since<br />

2006, a board member of the American Friends of<br />

Canadian Nature (AFCN) since 2018, and Board<br />

Chair of AFCN since 2022.<br />

3<br />

1<br />

4<br />

Through a collaboration with Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Inc., a<br />

Mi’gmaq rights-based organization and the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>), the land’s original stewards are plying their<br />

expertise while renewing their connections to the land at the newly<br />

created Simogwik Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA)<br />

in southeast New Brunswick.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> transferred the 44-hectare parcel last fall to Keki’namuanen<br />

Msit Wen Wlo’tmnen Nmaqami’kminu, a Mi’gmaq land trust that aims<br />

to maintain the land’s ecological integrity and conserve biodiversity,<br />

while also promoting Mi’gmaq heritage, culture and language.<br />

The Simogwik IPCA is small, but vibrant, and is home to white<br />

birch and snowshoe hare, golden-crowned kinglet and other birds.<br />

Its forests and wetlands protect these species and support a people’s<br />

profound connection to the land.<br />

“With its bounty of waterways and access to both the Northumberland<br />

Strait and the Bay of Fundy, Simogwik was both an important<br />

communal area and a well-travelled trade route,” said Chief Rebecca<br />

Knockwood of Amlagog (Fort Folly) First Nation.<br />

“We are honoured to partner with Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn Inc. in creating<br />

this IPCA,” added Paula Noel, <strong>NCC</strong>’s program director in New<br />

Brunswick. “Conservation that supports Indigenous leadership and cultural<br />

connections to the land is an important form of Reconciliation.”<br />

With this project complete, the lands, waters, plants and animals of<br />

the Simogwik IPCA will be protected for the next seven generations.<br />

White birch,<br />

a culturally<br />

important<br />

species to<br />

the Mi'gmaq<br />

people, is<br />

abundant on<br />

the IPCA.<br />

ANDREW HEREYGERS.<br />

AFCN is an IRS registered 501(c)(3) charity in New York State,<br />

whose mission is to support the identification, preservation<br />

and management of lands in Canada by working with key<br />

16 WINTER conservation <strong>2023</strong> partners and the support of U.S. funders.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

4<br />

Newly established<br />

reserve<br />

PORT L’HEBERT, NS<br />

FERNANDO LESSA; FIONA BROOKS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; CAROLINE DKS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

Reginald Hill Conservation Area, BC.<br />

2<br />

A win for the<br />

West Coast<br />

SALT SPRING ISLAND, BC<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is protecting some of<br />

British Columbia’s rarest woodland<br />

ecosystems on more than<br />

160 hectares on Salt Spring<br />

Island, off the coast of Victoria.<br />

Reginald Hill Conservation Area<br />

is full of life, nurturing a maturing<br />

Coastal Douglas-fir forest, mossy<br />

rock outcroppings, Garry oak<br />

plant communities, rocky bluffs<br />

and wetlands.<br />

Coastal Douglas-fir ecosystems<br />

make up only 0.3 per<br />

cent of the province’s land base.<br />

Despite its rarity, the habitats<br />

found within it are essential to<br />

the survival of some of BC’s most<br />

at-risk species, like sharp-tailed<br />

snake and a lichen known as<br />

peacock vinyl.<br />

This conservation area also<br />

adds to a network of already<br />

established parks and other protected<br />

lands to create a larger<br />

connected area for wildlife to<br />

thrive and move freely.<br />

Read more at:<br />

natureconservancy.ca/reginaldhill.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

3<br />

Rolling up the<br />

shirt sleeves<br />

ÎLE AUX GRUES, QC<br />

Located in the heart of the<br />

St. Lawrence River, about<br />

80 kilometres east of Quebec<br />

City, lies Île aux Grues. It is recognized<br />

as a high biodiversity<br />

site in Quebec — over 200 bird<br />

species nest or stop to refuel<br />

here during migration.<br />

But Île aux Grues is also<br />

home to a formidable invader:<br />

phragmites, also known as common<br />

reed. This invasive plant<br />

degrades the quality of wetlands<br />

by depriving wildlife of their<br />

habitats and by crowding out<br />

native plant species.<br />

As profiled in the 2022 summer<br />

issue of the <strong>NCC</strong> magazine,<br />

staff recently began a project to<br />

tackle the invader. After mowing<br />

an area measuring two hectares,<br />

staff and local experts then used<br />

an industrial sewing machine to<br />

connect large tarps together. Placing<br />

the tarps over the colonies<br />

blocks out sunlight and causes<br />

the plants to die. Staff continue<br />

to monitor and maintain the area,<br />

and plan to plant native species<br />

here in a few years, helping the<br />

rich biodiversity here thrive.<br />

The Haley Lake Nature Reserve<br />

provides critical habitat for<br />

several species at risk, including<br />

the globally rare boreal felt lichen.<br />

It is an essential stopover<br />

site for migratory birds. Haley<br />

Lake is located within an Important<br />

Bird Area in the community<br />

of Port l’Hebert, on Nova Scotia’s<br />

south shore. This newly established<br />

reserve is comprised of<br />

610 hectares of healthy and intact<br />

Wabanaki forest, coastal barrens,<br />

freshwater wetlands and<br />

lake shoreline. The reserve is<br />

near four federally established<br />

migratory bird sanctuaries that<br />

support thousands of breeding<br />

and overwintering waterfowl.<br />

The area’s forests are home to<br />

significant populations of uncommon<br />

and rare lichens, including<br />

Nova Scotia’s official lichen: blue<br />

felt lichen.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is working collaboratively<br />

with partners of the Kespukwitk<br />

Conservation Collaborative to<br />

conserve at-risk species here.<br />

Established in 2017, the<br />

Kespukwitk Conservation Collaborative<br />

includes Mi’kmaq First<br />

Nations, non-government organizations,<br />

academic institutions,<br />

and federal and provincial government<br />

departments.1<br />

Boreal felt lichen.<br />

Evening primrose,<br />

Hastings Wildlife Junction, ON.<br />

Partner Spotlight<br />

Intact Financial Corporation is<br />

helping the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) deliver<br />

nature-based solutions in<br />

response to biodiversity loss<br />

and climate change.<br />

With its five-year commitment,<br />

Intact is investing in the<br />

protection and restoration of<br />

wetlands and other critical<br />

ecosystems across the country.<br />

This partnership is already active<br />

in Ontario (Hastings Wildlife<br />

Junction), New Brunswick<br />

(Wolastoq [St. John] River Valley)<br />

and Quebec (Quebec City<br />

Watershed - Leclerc).<br />

Intact is also supporting<br />

the development of a<br />

made-in-Canada protocol for<br />

wetland-based carbon offsets.<br />

Once available, the protocol<br />

will be a tool to increase<br />

conservation-based investments<br />

in Canadian wetlands.<br />

Intact is also supporting <strong>NCC</strong>'s<br />

work to improve metrics and<br />

quantify the benefits that<br />

wetlands provide to Canadians.<br />

This partnership highlights<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s accelerated pace of<br />

conservation in Canada, as<br />

well as Intact’s commitment<br />

to <strong>NCC</strong> and supporting<br />

nature-based solutions.

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Dancing in the dark<br />

By Esme Batten, program director – midwestern Ontario, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

When I would hear about the aurora<br />

borealis, I always imagined seeing<br />

it in northern Canada or on a trip<br />

abroad to somewhere like Iceland or Finland.<br />

I never imagined that I would have the privilege<br />

of seeing it here at home on the Saugeen<br />

Bruce Peninsula in southern Ontario.<br />

Shimmering aurora borealis, or aurora<br />

australis in the southern hemisphere, are<br />

caused by activity on the sun. A specific type<br />

of solar storm, called coronal mass ejections<br />

(CME), emits electrified gas and particles<br />

into space. When these charged particles<br />

reach and enter Earth’s magnetic field, typically<br />

three days after the CME event, this<br />

is when we see the aurora. Due to the shape<br />

of the Earth’s magnetosphere, or system of<br />

magnetic fields, some of the charged particles<br />

that make it through the magnetic field are<br />

directed to the poles down magnetic field<br />

lines. This is why we often see the lights at<br />

the poles, where these charged particles enter<br />

our atmosphere. When there are particularly<br />

strong solar storms, we start to see the<br />

lights at lower latitudes. When these charged<br />

particles interact with gases in the<br />

atmosphere, they produce differently coloured<br />

lights in the sky depending on the altitude<br />

where the particles collide. Green light<br />

is produced when the particles mix with oxygen<br />

at lower altitudes, and red at higher altitudes.<br />

Pink and red occur at low altitudes<br />

when particles collide with nitrogen, and hydrogen<br />

and helium shine purple and blue.<br />

In late March, I was watching the aurora<br />

forecasts released by the National Oceanic<br />

and Atmospheric Administration to see if<br />

I had a chance to see the aurora at home.<br />

Since falling in love with astrophotography<br />

in 2019, I have had several opportunities to<br />

capture the movement of the aurora as a faint<br />

glow along the horizon, but these forecasts<br />

were predicting stronger storms than I had<br />

ever witnessed. Driving home with my partner<br />

that evening, we started to see the aurora<br />

before the skies were fully dark. My excitement<br />

was building. I rushed home to grab<br />

my camera gear and threw on some warm<br />

clothes before running out the door. I had<br />

been dreaming of shooting the stars in a cave<br />

along Georgian Bay, and knew that I needed<br />

to shoot the aurora there.<br />

I rushed along the Bruce Trail to the<br />

shoreline, dodging icy patches under the light<br />

of my headlamp and the stars. Once I reached<br />

the cave, I took a minute to turn off my headlamp,<br />

and I closed my eyes to let them adjust<br />

to the dark. When I opened them, I could not<br />

believe what I was seeing. The lights were<br />

dancing all around and above me with vibrant<br />

greens not typically seen this far south.<br />

Usually, the lights look like faint grey bars<br />

moving along the horizon, and colours can<br />

only be seen through a longer exposure image<br />

captured with a camera. I laughed hysterically<br />

in excitement and awe at nature’s<br />

beauty while I set up my camera. A friend<br />

joined me and we sat for hours, often just<br />

looking up at the sky without words. When I<br />

finally made it to bed around 4 a.m., the lights<br />

were still dancing. It still doesn’t feel real.<br />

We are likely to experience increased solar<br />

activity with more frequent and intense solar<br />

storms until mid 2025, meaning that the aurora<br />

will become more common. So, keep<br />

your eyes to the north in the coming months<br />

and hopefully you will also get to experience<br />

the majesty of the aurora.1<br />

ESME BATTEN.<br />

18 SUMMER <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LET YOUR<br />

PASSION<br />

DEFINE<br />

YOUR<br />

LEGACY<br />

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can define<br />

your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy of Canada,<br />

no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable habitats and the<br />

wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for generations to come.<br />

Order your Free Legacy Information Booklet today!<br />

Call Jackie at 1-877-231-3552 x2275 or visit DefineYourLegacy.ca

YOUR<br />

IMPACT<br />

Conserving<br />

coastal<br />

habitat<br />

Your support has<br />

ensured the conservation<br />

of an additional<br />

14 hectares at the<br />

Dr. Bill Freedman<br />

Nature Reserve in<br />

Nova Scotia. Located<br />

along the popular<br />

High Head Trail, this<br />

new area features<br />

undisturbed coastal<br />

habitat, including<br />

barrens and rocky<br />

coastline. This natural<br />

area is an important<br />

stopover for migratory<br />

shorebirds that forage<br />

on the barrens’ plentiful<br />

crowberries. The<br />

exposed granite barrens<br />

are ideal habitat<br />

for rare coastal plants.<br />

Big win for the Great Lakes<br />

Dr. Bill Freedman Nature Reserve, NS.<br />

Lake Superior’s largest privately owned island has now been protected, thanks to<br />

your support. Batchewana Island’s 27 kilometres of shoreline encircle more than<br />

2,000 hectares of mature and intact forests and wetlands. The work to steward the<br />

property continues. To learn more and donate to help care for the island property,<br />

visit natureconservancy.ca/batchewana.<br />

Batchewana Island, ON.<br />

Thank you for all you do for nature in Canada!<br />

ANDREW HERYGERS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; GARY MCGUFFIN.<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: PAUL ZIZKA; BRENT CARVER.