NCC Magazine, Fall 2023

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

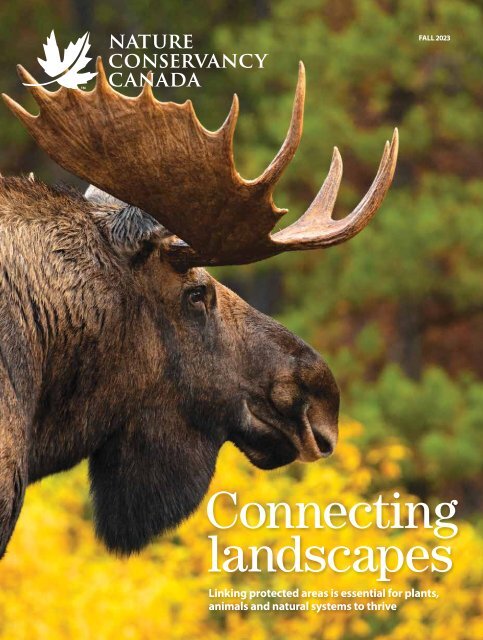

FALL <strong>2023</strong><br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

Connecting<br />

landscapes<br />

Linking protected areas is essential for plants,<br />

animals and natural systems to thrive<br />

WINTER 2021 1

FALL <strong>2023</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

4 People power<br />

Fuelling restoration from coast to coast.<br />

6 Lac Frye Nature Reserve<br />

This Important Bird Area in New<br />

Brunswick is a feast for a bird lover’s eyes.<br />

7 Less can be more<br />

Small actions, like restoration in your<br />

garden, can increase our resilience<br />

in the face of climate change and<br />

biodiversity loss.<br />

7 Backpack essentials<br />

The Yukon’s landscapes provide<br />

endless photographic opportunities<br />

for 16-year-old Evan Howells.<br />

8 Making connections<br />

Read about the first of four CARE<br />

principles — connected — and<br />

how it’s creating meaningful<br />

conservation outcomes.<br />

12 Spotted wintergreen<br />

This threatened species is found in<br />

only one place in Canada.<br />

14 Future-proofing<br />

conservation<br />

Meet the next generation of applied<br />

conservation scientists.<br />

16 Project updates<br />

Huge win for grasslands in BC; an island<br />

paradise in Ontario; restoring natural and<br />

cultural connections in Quebec.<br />

18 At home on the water<br />

Whether in Iran or Canada, there’s<br />

no place like home.<br />

Digital extras<br />

Check out our online magazine page with<br />

additional content to supplement this issue,<br />

at nccmagazine.ca.<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

365 Bloor Street East, Suite 1501<br />

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4W 3L4<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca | Phone: 416.932.3202 | Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is the country’s unifying force for nature. We seek<br />

solutions to the twin crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate change through large-scale,<br />

permanent land conservation. <strong>NCC</strong> is a registered charity. With nature, we build a thriving world.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC® is not responsible for any calculations<br />

on saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed in Canada with vegetable-based inks by Warrens Waterless Printing.<br />

This publication saved 28 trees and 25,920 litres of water*.<br />

CREATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM. PHOTO: GUILLAUME SIMONEAU (KENAUK, QC). COVER: MARK RAYCROFT.<br />

*<br />

2 FALL <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Featured<br />

Contributors<br />

ETIENNE BOISVERT.<br />

Dear friends,<br />

I<br />

have been amazed by nature since my childhood, wanting to<br />

protect all the wonders it has to offer. With the climate crisis<br />

and the decline of species, I care even more about taking action<br />

to increase its resiliency.<br />

It’s perhaps no surprise that at the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>), we CARE about nature every day. You see, for nature to<br />

thrive, protected and conserved areas need to be Connected, have<br />

Adequate quality habitats, be Representative of all species and be<br />

managed Effectively. Together, those principles represent an internationally<br />

recognized framework to support resilient landscapes. If<br />

the places we conserve meet these criteria, landscapes will be able<br />

to withstand the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss. And<br />

if they are resilient, then we feel confident we are building a thriving<br />

world with nature.<br />

In fact, CARE has become such an important lens for our work<br />

here at <strong>NCC</strong>, that we’re going to feature it over the next four issues<br />

of the <strong>NCC</strong> magazine.<br />

In this issue, we start the series off with the C in CARE: connected.<br />

As Dominique Ritter explains in her feature story, connectivity is<br />

important in all aspects of our work. It can mean a small passage to<br />

allow frogs to cross a road safely, or a large wilderness corridor for<br />

wide-ranging mammals to move within. Connected landscapes can<br />

ensure that when faced with severe weather events or the threat of<br />

invasive species, plants and animals can continue to thrive throughout<br />

their range. Connected landscapes can also be places where<br />

people spend time in and care for nature.<br />

Connecting landscapes and being connected to landscapes is vital.<br />

Thank you for the care you show in supporting Canada’s nature.<br />

Yours in nature,<br />

Marie-Michele Rousseau-Clair<br />

Marie-Michele Rousseau-Clair<br />

Chief conservation officer<br />

Dominique Ritter<br />

is a writer and editor<br />

based in Quebec’s<br />

Laurentians. She’s the<br />

former editor-in-chief<br />

of Reader’s Digest<br />

and several custom<br />

magazines for Bookmark,<br />

and has also<br />

worked at The Canadian<br />

Encyclopedia and<br />

Adbusters. She wrote<br />

“Making connections,”<br />

page 8.<br />

Chanelle Nibbelink<br />

is a Canadian-American<br />

illustrator who<br />

enjoys applying<br />

conceptual thinking<br />

and stylistic exploration<br />

to all of her<br />

editorial, publishing<br />

and advertising<br />

projects. She<br />

illustrated “At home<br />

on the water,” page<br />

18, and “Less can be<br />

more,” page 7.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2023</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

Conservation<br />

Volunteer removing<br />

encroaching shrubs<br />

to restore species at<br />

risk habitat, Ethier<br />

Sandhills, MB.<br />

50 per cent of the<br />

encroaching juniper<br />

has been removed.<br />

People<br />

power<br />

Conservation Volunteers are fuelling<br />

restoration efforts coast to coast<br />

Once the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) conserves a natural area,<br />

there may be areas that need some<br />

CARE to return them to a connected, adequate,<br />

representative and effective ecosystem. Restoration<br />

activities, like planting native plants and<br />

removing invasive ones, cleaning up debris and<br />

rehabilitating altered natural features, can help<br />

ensure the landscapes under our care are thriving<br />

and resilient. This work can take years of<br />

effort and a lot of elbow grease.<br />

One pair of hands can only do so much, but<br />

as the saying goes, many hands make light<br />

work. Each year, our Conservation Volunteers<br />

play a vital role in restoring diverse ecosystems<br />

across Canada.<br />

The impact of our Conservation Volunteers<br />

is a testament to the power of collective action.<br />

Not only do they help <strong>NCC</strong> staff accomplish<br />

the work we simply couldn’t do alone, but our<br />

volunteers also inspire and empower communities<br />

to forge a deeper connection with nature.<br />

Thank you to all our Conservation Volunteers<br />

for their invaluable support in creating a thriving<br />

world with nature.<br />

READ MORE ABOUT OUR<br />

CONSERVATION VOLUNTEERS<br />

AND THEIR SUCCESSES ONLINE:<br />

CONSERVATIONVOLUNTEERS.CA<br />

LIL CREEK PHOTO & VIDEO.<br />

4 FALL <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

ALBERTA<br />

Adopt a patch<br />

If you’ve ever spent time trying to rid your garden of weeds, you know<br />

that it takes hard work and perseverance. Now imagine trying to weed<br />

a property 100 times that size! That’s not a single-handed job. And<br />

that’s why Conservation Volunteers at Golden Ranches Conservation<br />

Area are helping remove and control invasive plants that are growing<br />

among the 110,000 native trees and shrub seedlings that were planted<br />

by Project Forest as part of a multi-year restoration project. Volunteers<br />

have been trained and assigned patches to adopt and weed repeatedly<br />

over the summer. Over time, their efforts will prevent these unwanted<br />

weeds from reproducing and allow native plants to thrive. To learn<br />

more, visit natureconservancy.ca/adopt-a-patch.<br />

8,867<br />

SQUARE<br />

METRES<br />

of weed patches targeted<br />

to prevent them from<br />

becoming larger and<br />

more difficult to control.<br />

3,000<br />

SEEDLINGS<br />

including white spruce, jack<br />

pine, white birch, red-osier<br />

dogwood and chokecherry<br />

have been planted since 2017.<br />

SASKATCHEWAN<br />

Giving nature some TLC<br />

Located 90 minutes north of Saskatoon, Meeting Lake 03 features close to<br />

200 hectares of woodlands, wetlands and grasslands. Parts of this area are threatened<br />

by habitat fragmentation, wetland loss and the removal of plants. That’s why<br />

Conservation Volunteers joined forces to plant 400 white spruces as part of an<br />

ongoing restoration project, which aims to bring this project back to its full glory.<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: <strong>NCC</strong>; <strong>NCC</strong>; ANDREA MOREAU/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

MANITOBA<br />

Students<br />

safeguard<br />

the sandhills<br />

Not only is Ethier Sandhills,<br />

located 88 kilometres<br />

southwest of Brandon,<br />

home to a number of<br />

native plants, but it also<br />

provides important<br />

habitat for Manitoba’s only<br />

lizard: prairie skink. And<br />

a team of student volunteers<br />

from Assiniboine<br />

Community College’s Land<br />

and Water Management<br />

program have been<br />

lending a hand to ensure<br />

the landscape there<br />

provides healthy habitat<br />

for these species. In the<br />

last two years alone, the<br />

team cleared significant<br />

areas of encroaching<br />

aspen stands and juniper<br />

shrubs, ensuring native<br />

plants and species have<br />

room to thrive. More work<br />

is planned for this fall, and<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> and the students are<br />

excited to continue these<br />

restoration efforts.<br />

ONTARIO<br />

Bend it like Willow Creek<br />

Willow Creek flows slowly through the Minesing Wetlands, one of <strong>NCC</strong>’s largest and least disturbed<br />

wetlands in southern Ontario. But it wasn’t always this way. Historical dredging of the wetlands for<br />

agricultural purposes led to an overload of sediment, reducing the channel’s ability to absorb and<br />

filter water. It also degraded habitat for the species that relied on the creek and its beds. The Nottawasaga<br />

Valley Conservation Authority and <strong>NCC</strong> have teamed up with volunteers to recreate the<br />

stream’s natural meander, by submerging coniferous trees in the creek along the banks. Post-restoration<br />

monitoring indicates that the aquatic bug community is more diverse (more bug groups).<br />

QUEBEC<br />

Rooting for<br />

turtles<br />

Turtles can be very picky during<br />

nesting season. At the Parc des<br />

Rapides-du-Cheval-Blanc in the<br />

west end of Montreal, buckthorn<br />

was invading a regularly used<br />

turtle nesting site. Conservation<br />

Volunteers removed the invasive<br />

species to protect this natural<br />

area, conducted nesting surveys<br />

and submitted sightings to local<br />

turtle monitoring project:<br />

carapace.ca.<br />

250<br />

SQUARE METRES<br />

are now turtle friendly.<br />

NOVA SCOTIA<br />

Youth for Boar’s Head<br />

One of the many benefits of being a Conservation<br />

Volunteer is that each event is a learning experience.<br />

And while at the Boar’s Head Nature Reserve<br />

shoreline cleanup, on the west coast of the island<br />

and surrounded on every side by the Bay of Fundy,<br />

volunteers literally participated in a community-based<br />

learning program. For the second year in<br />

a row, a group of Grade 10 students from Islands<br />

Consolidated School, along with local community<br />

members, joined forces at the event. Volunteers<br />

removed 19 extra-large garbage bags worth of<br />

debris from a 500-metre stretch of shoreline. To learn<br />

more, visit natureconservancy.ca/boars-head.1<br />

500<br />

METRE<br />

stretch of shoreline debris cleared.<br />

1KM<br />

of stream restored<br />

since 2010.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2023</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

Gulf of St. Lawrence<br />

<br />

N<br />

Lac Frye<br />

Nature Reserve<br />

Lac Frye<br />

Route 113 Highway<br />

Lac Frye<br />

Nature Reserve<br />

Bird lovers, feast your eyes on the many feathered friends feeding<br />

and nesting around the Lac Frye Nature Reserve’s coastal pond<br />

Lac Frye is one of six nature reserves<br />

protected by the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) on Miscou Island.<br />

This 54-hectare nature reserve is located at<br />

the tip of the island, at the northernmost<br />

point of New Brunswick. The island has been<br />

designated as an Important Bird Area — its<br />

wetlands and coastlines are a critical stopover<br />

point for migratory birds. Its beaches<br />

are also used as a nesting ground by endangered<br />

piping plovers.<br />

Birders can meander along the boardwalk<br />

and enjoy the sights from the viewing<br />

platform that overlooks a large coastal<br />

pond, which is surrounded by a sand<br />

barrier beach, salt marsh and forest.<br />

Come fall, Miscou Island’s expansive<br />

bogs light up in spectacular shades of<br />

red. And if that’s not enough to pique your<br />

interest, many species of shorebirds,<br />

waterfowl and plants can be spotted here,<br />

including the at-risk Gulf of St. Lawrence<br />

aster. Who knows, maybe you’ll even get<br />

lucky enough to feast your eyes on the<br />

hundreds of northern gannets that can be<br />

seen just off the coast.1<br />

LEGEND<br />

-- Boardwalk<br />

Viewing platform<br />

P Parking<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• alder flycatcher<br />

• American goldfinch<br />

• belted kingfisher<br />

• common tern<br />

• common<br />

yellowthroat<br />

• dunlin<br />

• great blue heron<br />

• green-winged teal<br />

• Gulf of St. Lawrence<br />

aster<br />

• least sandpiper<br />

• northern gannet<br />

• northern harrier<br />

• piping plover<br />

• red-eyed vireo<br />

• red-winged<br />

blackbird<br />

• semipalmated<br />

sandpiper<br />

• Swainson’s thrush<br />

• swamp sparrow<br />

• yellow warbler<br />

• whimbrel<br />

LEARN MORE<br />

Visit natureconservancy.ca/lacfrye<br />

MAP: JACQUES PERRAULT. PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT: ANDREW HERYGERS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; MIKE DEMBECK;<br />

ROBERT MCCAW; ANDREW HERYGERS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

6 FALL <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

ACTIVITY<br />

CORNER<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

ILLUSTRATION: CHANELLE NIBBELINK. PHOTO: CATHIE ARCHBOULD.<br />

Restoration:<br />

Less can be more<br />

Restoration — assisting in ecosystem recovery<br />

— is a key part of the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) work across the country. On a<br />

large scale, this work helps provide wildlife habitat<br />

and increases resiliency to climate change. But<br />

small actions can also contribute to the greater<br />

good. Read on to learn about how you can help fill<br />

in the pieces of the restoration puzzle.<br />

LET IT BE<br />

Press pause on the yard work and make a<br />

difference for Canadian wildlife. In autumn, fallen<br />

leaves, as well as plant stalks and seedheads,<br />

can provide habitat for small mammals, insects,<br />

amphibians and reptiles. Dead tree branches and<br />

areas of uncovered soil can be a place for native<br />

bees to overwinter.<br />

With the time you save, you’ll have lots of<br />

opportunity to observe and learn more about<br />

the species you encounter, using a field guide<br />

or app like iNaturalist.<br />

BACK WHERE THEY BELONG<br />

Replacing plants with native species and replacing<br />

lawns with native ground cover is a great way<br />

to contribute to restoration. Use the QR code<br />

below to learn about native gardening and select<br />

species suited to where you live. Less lawn means<br />

more habitat for wildlife. It also means less water,<br />

fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides. This reduces<br />

waste and makes a healthier place for people<br />

and wildlife.<br />

And if you take care in choosing the right species,<br />

you may notice an increase in butterflies, bees and<br />

other pollinators when your plants bloom.1<br />

TO LEARN MORE,<br />

VISIT <strong>NCC</strong>’S SMALL ACTS<br />

OF CONSERVATION<br />

Frame of mind<br />

Evan Howells, 16, one of this year’s Nature Inspiration Award<br />

youth finalists*, is grateful to be growing up in the Yukon,<br />

surrounded by nature and its endless photo opportunities<br />

Ilive in Whitehorse, known as the wilderness city, where a backpack adventure is<br />

only minutes away. I never leave home without my backpack, and an essential<br />

item I always pack is my camera. I like to connect to nature by capturing photos<br />

of whatever I see around me — from insects to plant life.<br />

In recent years, I learned the importance of using photography to document<br />

observations for my multi-year science fair project. At 13, I started collecting data<br />

for the first study that compared pollen foraging patterns of native bumble bees and<br />

honey bees in natural landscapes in Southern Lakes, Yukon. Each summer, I took<br />

photos of the study sites, including bees and flowers during each visit. After identifying<br />

bee pollen samples under a microscope, I used the photos for cross-referencing<br />

the flowers blooming in each collection period.<br />

Photography was also an integral part of communicating my study results online<br />

and in designing my science fair display. At the <strong>2023</strong> Canada-Wide Science Fair,<br />

I was honoured to receive a medal for my project. I hope my study findings will raise<br />

awareness of the needs of native bumble bees and further guide beekeeping and<br />

landscaping practices to maintain their populations locally.<br />

Spending lots of time in the meadows of the Southern Lakes region has made it<br />

one of my favourite nature spots in the Yukon. I plan to go on many hikes there in the<br />

future, and I’ll be sure to take my camera along.1<br />

*An annual award hosted by the Canadian Museum of Nature.<br />

FALL <strong>2023</strong> 7

Making<br />

connections<br />

Collaboration between conservationists is helping create meaningful<br />

outcomes in habitat preservation, education and research<br />

BY Dominique Ritter<br />

8 FALL <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

GUILLAUME SIMONEAU.<br />

Connection is visible throughout nature,<br />

like here, between tree, rock, land and<br />

sky in Kenauk. Inset: Lac Papineau,<br />

Kenauk Nature Reserve, QC.<br />

In summer, King Kong sticks close to his<br />

home range. The eight-and-a-half-year-old bull<br />

moose — who earned his nickname thanks to his<br />

imposing stature — spends his nighttime hours<br />

feeding on new-growth poplars and beech. During<br />

the warm daytime hours, he can be found digesting in the<br />

shade of large fir trees, reclined on a cool, moist bed of moss,<br />

with his legs tucked up by his belly and the left side of his<br />

140-centimetre antlers, with its signature downward-facing<br />

tine, resting on the ground to support his handsome head.<br />

This munching-and-napping routine all sounds quite leisurely<br />

until you consider the effort of eating 22 to 25 kilograms<br />

of vegetation per day, not to mention the substantial<br />

challenges ahead. Because, come fall, King Kong will set off<br />

on a vital journey: fathering next year’s calves.<br />

Starting in the first days of September, King Kong transforms<br />

from homebody to travelling salesman. From his tract<br />

in the Kenauk nature reserve, in southwest Quebec, he has<br />

to signal to the female moose in the area that he is ready,<br />

willing. It’s time to roam the deep temperate forest.<br />

King Kong begins his fall pilgrimage by covering about<br />

10 square kilometres to rub his molting antlers, which have<br />

been carefully doused in his testosterone-accented urine, on<br />

trees. It’s not unusual for five or six females to come calling<br />

in response to this olfactory marketing campaign. It’s also<br />

not unusual for several young bulls to travel to King Kong’s<br />

patch and try to persuade a female that the big bull isn’t<br />

quick enough to satisfy.<br />

All to say that while most moose don’t typically migrate,<br />

they do move around — quite a bit. And this freedom to<br />

move is absolutely essential to their health, their ability to<br />

successfully reproduce and the population’s long-term<br />

survival, especially on a warming planet. Accommodating<br />

that movement is one of the key considerations when<br />

conservationists talk about ecological connectivity.<br />

Building a network<br />

A common set of guiding principles is indispensable if conservationists<br />

are to work toward shared goals that translate<br />

across ecosystems and boundaries to create long-term<br />

solutions. To that end, most systematic conservation plans<br />

worldwide — including those of the Nature Conservancy of<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2023</strong> 9

Connections abound in Kenauk.<br />

Continued from previous page<br />

Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) — follow four key principles:<br />

connectivity, adequacy, representation and<br />

effectiveness (often referred to by the acronym<br />

CARE).<br />

“Connectivity is about how much landscapes<br />

allow species to move and ecosystem<br />

processes to occur. It’s directly related to<br />

resilient landscapes and the genetic diversity<br />

of populations,” explains Marie-Andrée<br />

Tougas-Tellier, project manager for <strong>NCC</strong><br />

and its Quebec Ecological Corridors Initiative<br />

(QECI).<br />

We’re at the edge of the 93-hectare Lac<br />

Maholey, in Kenauk. It’s a rich source of the<br />

aquatic plants King Kong likes to eat in<br />

springtime. Looking out over a floating blanket<br />

of lily pads, there’s a great blue heron<br />

poised knee-deep in the shallows, searching<br />

for its next catch. The only human-made<br />

structure in view is the dock beneath our<br />

feet. But while this is ideal habitat for<br />

moose, they also need safe corridors to help<br />

them travel over wide expanses.<br />

Because of the area’s exceptional natural<br />

values, <strong>NCC</strong> has been partnering with the<br />

Kenauk Institute since 2013 to ensure its<br />

long-term care. At 26,500 hectares, it is one<br />

of the largest temperate forests dedicated<br />

to conservation and research in North<br />

America and significant habitat for species<br />

(112 rare species have been identified<br />

here in the past eight years).<br />

Kenauk also is important because it’s<br />

a crucial piece in a much wider natural<br />

network (see map inset, p. 11). This<br />

300-kilometre corridor, which stretches<br />

between the Adirondacks and Parc<br />

Mont-Tremblant, is vital to species — from<br />

Canada warbler to painted turtle, to wolf<br />

and black bear.<br />

People power<br />

Cary Hamel, <strong>NCC</strong>’s director of conservation in<br />

Manitoba, has spent close to three decades<br />

protecting land and easing the passage of<br />

wildlife from one area to another. One of his<br />

team’s challenges: continuing to conserve important<br />

habitats and restore connectivity in<br />

key areas between Riding Mountain National<br />

Park, about 250 kilometres northwest of<br />

Winnipeg, and Duck Mountain Provincial<br />

Park, to its north.<br />

“At the end of the day, if those parks<br />

end up being islands, completely developed<br />

all around, they’re going to lose ecological<br />

integrity and they’re going to lose species,”<br />

Hamel explains.<br />

Success in <strong>NCC</strong>’s conservation efforts<br />

isn’t dependent on keeping humans out; it’s<br />

dependent on bringing them in. “People are<br />

part of nature,” he says.<br />

With that in mind, Hamel and his team<br />

have been working within the Blue Wing<br />

corridor, a 106,578-hectare area separating<br />

Riding Mountain and Duck Mountain. Here,<br />

maintaining habitat for golden-winged warbler,<br />

moose and elk amid tracts of privately<br />

owned land is largely focused on building<br />

relationships in the community, based on<br />

shared values.<br />

Improving connectivity can look like the<br />

purchase of a piece of land or a conservation<br />

agreement in a critical movement corridor.<br />

But it can also be about innovative programs<br />

to help maintain grasslands and pastures<br />

and support livestock farmers, whose lands<br />

might otherwise be converted. Or it can look<br />

like students from the Waywayseecappo<br />

Off-campus School who have been coming<br />

out and working with Elders and <strong>NCC</strong> staff<br />

since 2018. They do a wide range of handson<br />

activities that benefit conservation, including<br />

restoration work on <strong>NCC</strong> properties,<br />

with the goal of improving movement<br />

across landscapes.<br />

“Our goal is to support vibrant rural communities<br />

where people can make a living, and<br />

nature is seen as part of the economy and not<br />

as a barrier to development,” says Hamel.<br />

Similarly in Quebec, <strong>NCC</strong> is leading an<br />

initiative to build alliances and accelerate its<br />

efforts. Launched in 2017, QECI is comprised<br />

of 10 organizations and hundreds of<br />

partners, and uses a collective approach to<br />

boost the conservation of ecosystems connected<br />

by natural corridors. The initiative<br />

includes municipal and regional governments,<br />

woodlot owners, farmers, environmental<br />

organizations and experts dedicated<br />

to protecting and conserving nature across<br />

borders. It’s a remarkable confluence of interests,<br />

not least of all because it’s the first<br />

time all key stakeholders have worked<br />

together on a common goal.<br />

Thanks to QECI, woodlot owners learn<br />

that their forest management work is also<br />

beneficial for wildlife corridors. And by leaving<br />

tree stumps and woody debris, they provide<br />

critical habitat for pileated woodpecker<br />

and salamander. In turn, <strong>NCC</strong> has learned<br />

much from woodlot owners, making it a mutually<br />

beneficial collaboration.<br />

“When we started, in 2017, not many<br />

people were working to conserve ecological<br />

GUILLAUME SIMONEAU.<br />

10 FALL <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

connectivity,” reflects Kateri Monticone, director<br />

strategic conservation and innovation<br />

at <strong>NCC</strong> in Quebec.<br />

“Now we hear it referenced more and more<br />

— in government, among the owners of woodlots,<br />

citizens, regional mayors,” says Monticone.<br />

“That’s a really great achievement.”<br />

Common knowledge<br />

Valerie Pankratz, executive director of Manitoba’s<br />

Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve,<br />

has spent two decades promoting connectivity<br />

and is credited with finding solutions to some<br />

of the area’s more divisive issues between<br />

farmers and conservationists.<br />

“Really what we’re trying to do is conserve<br />

and preserve biodiversity within the<br />

region and hope that we can entice people,<br />

through education and communication, to<br />

do the right thing,” she says. “We can’t tell<br />

people what to do; our job is to act as a conduit<br />

of information.”<br />

Sometimes, education about connectivity<br />

needs to focus on the threats to an ecosystem<br />

and what not to do, in order to support<br />

the local species. “Last week, we did<br />

a kids’ program in which we made zebra<br />

mussel replicas they could take home,” says<br />

Pankratz. Zebra mussels are an invasive species<br />

that take over an aquatic ecosystem by<br />

hoarding the nutrients and starving out native<br />

fish populations and the industries that<br />

depend on them.<br />

“Now the kids know what they look like,”<br />

says Pankratz, “and we hope they understand<br />

the importance of not moving the zebra<br />

mussels from one lake to another.”<br />

Freedom to roam<br />

Back at Kenauk, improving connectivity<br />

remains, of course, an ongoing challenge.<br />

A recent study examining habitat loss in the<br />

transborder corridor from the Adirondacks to<br />

the Laurentians and up to Parc Mont-Tremblant,<br />

between 2000 and 2015, found that, as<br />

a species, moose had experienced the largest<br />

impact: their habitat shrank by 26 per cent.<br />

Compounding this deficit are the ongoing<br />

fragmentation and degradation of habitats<br />

and the growing pressures of climate change.<br />

“With climate change, animal habitats are<br />

shifting north at a rate of four kilometres per<br />

year. So, animals are going to follow their<br />

habitats to survive, and ecological corridors<br />

are going to become more and more important,”<br />

says Monticone, who notes several<br />

climate refugee species have already been<br />

spotted in Quebec, among them possums.<br />

Despite ongoing changes, she remains optimistic.<br />

“There’s a lot of hope in action.<br />

Together, we go further.”<br />

Action — though of a different variety<br />

— is also one of King Kong’s primary goals.<br />

Come October, driven to maintain his status<br />

as one of Kenauk’s most successful breeding<br />

males, he will undertake a second round of<br />

reproductive outreach, this time travelling<br />

up to 10 kilometres in a single night, in order<br />

to find any fertile females he may not have<br />

encountered in the first round.<br />

Over the past five years, King Kong’s dedication<br />

to these efforts have produced impressive<br />

results: around 30 surviving calves. One<br />

day, one of them might take over as the new<br />

king of Kenauk.1<br />

CARE<br />

It’s perhaps no surprise that at<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>, we CARE about nature every<br />

day. You see, for nature to thrive,<br />

protected and conserved areas<br />

need to be Connected, have<br />

Adequate quality habitats, be<br />

Representative of all species and<br />

be managed Effectively. Together,<br />

those principles represent an<br />

internationally recognized<br />

framework to support the creation<br />

of resilient landscapes. If the<br />

places we conserve meet these<br />

criteria, landscapes will be able to<br />

withstand the impacts of climate<br />

change and biodiversity loss.<br />

And if they are resilient, then we<br />

feel confident we are building<br />

a thriving world with nature.<br />

SEAN FEAGAN/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF. INSETS: DOUG DERKSEN; LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF. MAP: <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Quebec Ecological Corridors Initiative vision<br />

Key zone for connectivity<br />

Public or private protected area<br />

Public managed area<br />

Ecological corridors restoration area<br />

Ecological network<br />

vision of the QECI<br />

An important consideration in<br />

creating protected areas is<br />

ensuring that important places<br />

for biodiversity conservation are<br />

connected so that plants, animals<br />

and natural systems can survive.<br />

This is important for species’<br />

movement between habitat<br />

patches, to ensure an exchange of<br />

genetic material between locations.<br />

It is also becoming increasingly<br />

important to adjust to the<br />

effects of climate change and give<br />

species the opportunity to move<br />

as climate conditions change.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2023</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Spotted<br />

wintergreen<br />

This threatened species, once found in both Ontario and Quebec,<br />

is now only seen in southern Ontario<br />

GERRY BISHOP/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

12 FALL <strong>2023</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

This low-growing evergreen<br />

plant can reach 10 to 25 centimetres<br />

high. Its blue-green toothed<br />

leaves feature a white stripe along<br />

their mid-rib. The five-petalled<br />

flowers, which arise from a stalk<br />

atop the whorl of leaves,<br />

are pink or white.<br />

HABITAT<br />

This species occurs in<br />

well-drained sandy soil<br />

and oak-pine mixed<br />

forests and<br />

woodlands.<br />

RANGE<br />

Spotted wintergreen can<br />

be found in southern Ontario,<br />

the eastern U.S., most of Mexico<br />

and parts of Central America. In<br />

Canada, it is found in southern<br />

Ontario. Until recently, the species<br />

was spotted in Quebec as well,<br />

but it can no longer be found<br />

in this province.<br />

THREATS<br />

A threatened species,<br />

spotted wintergreen is at risk<br />

from habitat loss from<br />

development and habitat<br />

degradation from recreational<br />

activities.<br />

DAN HANSCOM/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO.<br />

What <strong>NCC</strong> is doing to protect habitat for this species<br />

Weston Family Conservation Science Fellow Amy Wiedenfeld is trying to understand whether some of the<br />

spotted wintergreen populations in Ontario are growing or shrinking, and what environmental factors may<br />

be contributing to the population changes. This information will help the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

natureconservancy.ca plan conservation or restoration activities to support this and other rare species.1<br />

HELP<br />

OUT<br />

Help protect habitat for<br />

species at risk at<br />

natureconservancy.<br />

ca/donate.<br />

FALL <strong>2023</strong> 13

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Future-proofing<br />

conservation<br />

Empowering students<br />

with the skills, experience<br />

and community they need<br />

to become tomorrow’s<br />

leaders in applied<br />

conservation science<br />

GUILLAUME SIMONEAU.<br />

14 FALL <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

GUILLAUME SIMONEAU.<br />

The next<br />

generation<br />

of leaders in<br />

applied conservation<br />

science are hard at<br />

work, thanks to the<br />

Weston Family<br />

Conservation Science<br />

Fellowship Program.<br />

The program supports<br />

and trains graduate<br />

students conducting<br />

Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

priority research on<br />

the conservation and<br />

management of important<br />

natural areas and<br />

biological diversity<br />

across Canada.<br />

The program aims to provide the fellows with<br />

relevant and unique learning opportunities<br />

that extend beyond their own research. Fellows<br />

engage with <strong>NCC</strong> staff and the organization’s<br />

work, and are offered opportunities<br />

for professional development. They develop<br />

a sense of community that fosters peer<br />

support, creating strong connections that<br />

will carry into their professional careers.<br />

Fellowships are awarded to graduate<br />

students conducting world-class applied<br />

conservation research that directly addresses<br />

pressing conservation challenges and <strong>NCC</strong><br />

priorities, including species at risk, ecological<br />

connectivity and invasive species.<br />

Fellowships for specific research projects<br />

are typically advertised in the fall, for master’s<br />

or PhD students to begin their studies the<br />

following summer or fall. The first cohort of<br />

fellows began their studies in fall 2020.1<br />

LEARN MORE ABOUT<br />

THE FELLOWS, THEIR<br />

RESEARCH, AND HOW TO<br />

APPLY FOR A FELLOWSHIP<br />

ZACHARY MOORE<br />

Master’s student, University of Manitoba<br />

(2020–present)<br />

Zachary Moore will tell you that conservation<br />

theory is for the birds. He is studying<br />

the response of grassland songbirds to<br />

vegetation structure and cattle grazing on<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> properties in the Waterton Park Front<br />

in Alberta. His research will inform best<br />

management practices to support grassland<br />

songbirds.<br />

AMY WIEDENFELD<br />

PhD student, University of Lethbridge<br />

(2022–present)<br />

Amy Wiedenfeld believes plants are cool<br />

and wants to dispel the misperception that<br />

they are uninteresting. She is researching<br />

whether populations of four rare plants in<br />

southern Ontario are increasing or decreasing<br />

over time, the rate of change, and how<br />

environmental barriers such as soil quality<br />

impact this.<br />

JESSICA SÁNCHEZ-JASSO<br />

PhD student, University of Manitoba<br />

(2022–present)<br />

Jessica Sánchez-Jasso feels as though her<br />

dreams have come true. With her love of<br />

butterflies and expertise in land management<br />

and GIS, she wants to show the role<br />

that butterflies play within ecosystems. She<br />

studies how prairie management affects<br />

two endangered butterflies in Manitoba:<br />

Poweshiek skipperling and Dakota skipper.<br />

EMILY TRENDOS<br />

PhD student, University of Guelph<br />

(2020–present)<br />

If you ask Emily Trendos, there’s nothing<br />

creepy about the crawlies she studies.<br />

She is researching the growth and survival<br />

of the endangered mottled duskywing<br />

butterfly in southern Ontario. Her research<br />

will provide information to support both<br />

current populations and future reintroductions<br />

of this species into suitable habitat.<br />

BRIELLE REIDLINGER<br />

Master’s student, University of Saskatchewan<br />

(2022–present)<br />

Brielle Reidlinger is passionate about the<br />

Prairies, birds and ranching. With the help<br />

of the fellowship, she hopes her research<br />

will help further the understanding of<br />

prairie songbirds and best grazing practices.<br />

She is comparing the impact of grazing<br />

cattle versus bison on grassland songbirds<br />

at Old Man on His Back Prairie and Heritage<br />

Conservation Area in Saskatchewan.<br />

JUSTIN KRELLER<br />

Master’s student, Carleton University<br />

(<strong>2023</strong>–present)<br />

Justin Kreller will use his GIS skills and<br />

passion for ecology and conservation to<br />

study some of Canada’s most invasive plants.<br />

He will use computer models to map their<br />

distribution and forecast their spread and<br />

future burden across the country.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

FALL <strong>2023</strong> 15

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

A huge win for grasslands<br />

BUNCHGRASS HILLS CONSERVATION AREA, BC<br />

1<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

2<br />

3<br />

In June, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) celebrated<br />

one of the largest private grassland conservation achievements in<br />

BC with the establishment of the Bunchgrass Hills Conservation<br />

Area. The area’s more than 6,100 hectares of native grasslands<br />

offer vital habitat and connectivity for the species that live in the<br />

Thompson-Nicola region and within the traditional territories of<br />

the Secwépemc, Nlaka’pamux and Syilx Nations.<br />

The area’s rolling hills are covered in bluebunch wheatgrass and<br />

other native grasses, and are punctuated by Douglas-fir woodlands<br />

and scattered wetlands.<br />

Bunchgrass Hills offers important habitat for dozens of species<br />

iconic to BC’s interior. This includes several listed on the federal<br />

Species at Risk Act, such as Great Basin spadefoot toad, Great Basin<br />

gopher snake, American badger and Lewis’s woodpecker. Sharp-tailed<br />

grouse leks (mating sites) are also known to occur in the area, which<br />

indicates these grasslands are important breeding grounds for this<br />

provincially at-risk species.<br />

This project demonstrates the important contribution that<br />

private land conservation is making to our country’s climate and<br />

biodiversity goals.<br />

FERNANDO LESSA; FERNANDO LESSA. PORTRAIT: LA HALTE STUDIO.<br />

Nature is<br />

our lifeline<br />

“In 2021, we donated a large portion of our land<br />

to the Nature Conservancy [of Canada] with the<br />

belief and trust that it would be protected.<br />

“Why did we do it? It is about the future. Not so<br />

much my future or my husband’s future, but where<br />

we are going as a society. I believe that if we are<br />

lucky enough to be able to own land and it’s possible<br />

to protect it, then that is what we should do.<br />

“Nature is our lifeline. It’s not something outside of<br />

us that we need to protect; we are part of it. We are<br />

so interconnected, that if we don’t have trees, we<br />

don’t breathe. If we don’t have water, we cannot<br />

stay alive. We need to have these swaths of land<br />

that are full of forests and functioning ecosystems.<br />

“It’s not just how pretty the land is — I think of it<br />

as a survival mechanism. That’s why for me, it’s so<br />

important [to protect it].”<br />

~Ewa Dorynek Scheer has been an<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> donor since 2015<br />

These lands expand the protected areas in the southern<br />

flank of Quebec's Sutton Mountains and connect<br />

existing projects that are important for wide-ranging<br />

mammals, like black bear, bobcat and moose.<br />

Creating a corridor of protected areas allows these<br />

animals space to reproduce, raise their young and<br />

Bunchgrass Hills, BC.<br />

move in search of food.<br />

Inset: Checkerspot butterfly.<br />

16 WINTER <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

2<br />

Island paradise<br />

BATCHEWANA ISLAND, ON<br />

Kenauk, QC.<br />

LEFT TO RIGHT: GARY J. MCGUFFIN; MIKE CRANE; KENAUK NATURE.<br />

The future of Lake Superior’s largest privately<br />

owned island is now ensured. Batchewana<br />

Island boasts close to 30 kilometres of shoreline,<br />

which encircles more than 2,000 hectares of<br />

pristine forests and wetlands. Gray wolf, black<br />

bear, moose and more than 30 provincially<br />

significant bird species live in the island’s woods.<br />

Many fish, including endangered lake sturgeon,<br />

spawn in the shallows offshore.<br />

The old-growth forests and wetlands that<br />

cover the island store carbon, filter water and<br />

provide habitat to plants and animals, helping<br />

to slow the pace of climate change and biodiversity<br />

loss. The carbon stored here is equivalent<br />

to the energy used by over 500,000 homes<br />

each year. As the forest continues to mature,<br />

it pulls even more carbon dioxide out of<br />

Ci di cor seque core et aciduci aepere optatiis del<br />

the atmosphere.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has already raised 80 per cent of the<br />

$7.2 million needed to purchase and care for<br />

the property, thanks to the support of federal<br />

and provincial governments and private donors.<br />

To learn more or to donate, visit<br />

natureconservancy.ca/batchewana.<br />

Batchewana Island, ON. Black bear.<br />

3<br />

Restoring natural and<br />

cultural connections<br />

W8BANAKI NATION<br />

Recently, Indigenous artifacts — stone chips for<br />

manufacturing tools and pottery shards — were<br />

uncovered on two different <strong>NCC</strong> sites in Quebec:<br />

Lac du Portage and Île Bouchard. W8banaki and<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> used archaeology to assist with conserving<br />

the cultural heritage of Indigenous communities.<br />

This collaboration inspired a rich conversation<br />

about the role of conservation sites, their meaning<br />

for Indigenous communities and Indigenous<br />

traditional use of natural resources.1<br />

To learn more, visit natureconservancy.ca/archeology.<br />

Partner Spotlight<br />

The American Friends of Canadian<br />

Nature (AFCN) is a U.S. not-for-profit<br />

charity that supports land conservation<br />

efforts in Canada and the<br />

work of Canadian conservation<br />

organizations, including but not<br />

limited to the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>). U.S. taxpayers<br />

who would like to be part of a<br />

landscape-scale approach to North<br />

America’s conservation legacy can<br />

donate to the AFCN.<br />

Each U.S. dollar donated to AFCN<br />

can leverage up to $4 for conservation<br />

in Canada, thanks to<br />

match dollars from government<br />

funding, U.S. Fish and Wildlife<br />

Service and various Canadian<br />

conservation organizations.<br />

Nature knows no borders, and<br />

neither should conservation. In<br />

fact, many of Canada’s largest<br />

forests, mountain ranges and lakes<br />

extend well into the U.S., along<br />

with the habitats of species living<br />

in these areas. To successfully<br />

safeguard North America’s<br />

immense biodiversity, cross-border<br />

conservation efforts are essential.<br />

Support from AFCN has helped<br />

support projects from coast to<br />

coast, such as <strong>NCC</strong>’s work on Brier<br />

Island, NS, Reginald Hill, BC,<br />

Kenauk, QC, and The Yarrow, AB.<br />

Since landscapes and species in the<br />

U.S. directly benefit from conservation<br />

work done in Canada, American<br />

taxpayers are encouraged to<br />

support this vision. All contributions<br />

are tax-deductible under U.S. law.<br />

For more information:<br />

americanfriendscanadiannature.org.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

At home on the water<br />

By Saba Mozaffari, <strong>NCC</strong> communications intern in Atlantic Canada<br />

Growing up in a big city in Iran, a country with<br />

a vast and varying geography, I had little opportunity<br />

to explore and enjoy the outdoors. But<br />

each Iranian New Year, my family and I would visit the<br />

northern region of the country, where the air felt fresh<br />

and the sea was only a few steps away from our villa.<br />

The beautiful, lush greenery was mesmerizing, and it<br />

was an escape from busy city life.<br />

I always hoped to see more of my country. But by age<br />

16, I had moved to Canada, a new home with much to<br />

explore. My internships with the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) have allowed me to explore Atlantic Canada’s<br />

magnificent landscapes in my new home country.<br />

In 2022, while on vacation with a friend, I visited<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s Gaff Point Nature Reserve in Nova Scotia. With<br />

our hiking boots laced up and our water bottles filled,<br />

we headed out. That day was magical. The sun peeked<br />

through the trees, the sky was a clear, bright blue,<br />

and it was the perfect temperature. Having seen many<br />

pictures of Gaff Point, I knew what to expect, but it<br />

was much more beautiful than any photo could ever<br />

capture. At that moment, for the first time in years,<br />

I felt at home.<br />

To reach the trailhead, we crossed the stunning<br />

crescent of Hirtle’s Beach. I can still vividly recall the<br />

feeling of being surrounded by trees, the salty, refreshing<br />

scent of the ocean and the sounds of waves pulling<br />

in and drifting away.<br />

My favourite spot on the trail was an open area at the<br />

point where the Atlantic Ocean spreads out before us as<br />

far as the eye could see. We took a moment and sat on a<br />

safe and stable rock, admiring and appreciating the view.<br />

Breathing the ocean air, I knew this was where I was<br />

meant to be. The sound of waves smashing against the<br />

rocks, the bright sun above and the calm around were all<br />

I needed to realize that no matter how far away I was<br />

from my native country, I could always call this place<br />

my home.1<br />

CHANELLE NIBBELINK.<br />

18 FALL <strong>2023</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LET YOUR<br />

PASSION<br />

DEFINE<br />

YOUR<br />

LEGACY<br />

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can define<br />

your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy of Canada,<br />

no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable habitats and the<br />

wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for generations to come.<br />

Order your Free Legacy Information Booklet today!<br />

Call Jackie at 1-877-231-3552 x2275 or visit DefineYourLegacy.ca

YOUR<br />

IMPACT<br />

Protecting Canada’s Prairie grasslands<br />

With Prairie grasslands disappearing at an alarming rate, conserving this ecosystem is crucial.<br />

Thanks to you, a conservation agreement at McIntyre Ranch, in southern Alberta — the<br />

largest agreement of its kind in Canadian history — will ensure the protection of more than<br />

22,000 hectares of intact grasslands and wetlands. Grasslands store about a third of the world’s<br />

land-based carbon through their deep root systems. And by supporting McIntyre Ranch, part<br />

of the Nature Conservancy of Canada's (<strong>NCC</strong>'s) campaign to protect Canada’s Prairie grasslands,<br />

and in partnership with Ducks Unlimited Canada, not only are you making a positive<br />

impact for Canadians, but for the entire planet.<br />

Natural<br />

partners<br />

The Government<br />

of Canada's Natural<br />

Heritage Conservation<br />

Program continues to<br />

support the conservation<br />

of critical habitat.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> and program<br />

partners recently<br />

entered into a new<br />

three-year agreement<br />

to protect at least<br />

180,000 hectares.<br />

Since 2007, <strong>NCC</strong> and<br />

program partners<br />

have conserved<br />

nearly 800,000 hectares<br />

across Canada,<br />

including close to<br />

100,000 hectares<br />

of grasslands.<br />

LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF. LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

Community<br />

grazing<br />

groups<br />

Thanks to generous donors and<br />

partners like you, we are making<br />

a significant impact. <strong>NCC</strong>'s partnership<br />

work with local grazing<br />

groups supports conservation<br />

activities on 290,000 hectares of<br />

Prairie grasslands and sustains<br />

the livelihoods of local communities.<br />

These partnerships allow<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> to support conservation<br />

on about five per cent of the<br />

total remaining native prairie in<br />

Saskatchewan.<br />

Thank you for all you do for nature in Canada!