NCC Magazine Winter 2024

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

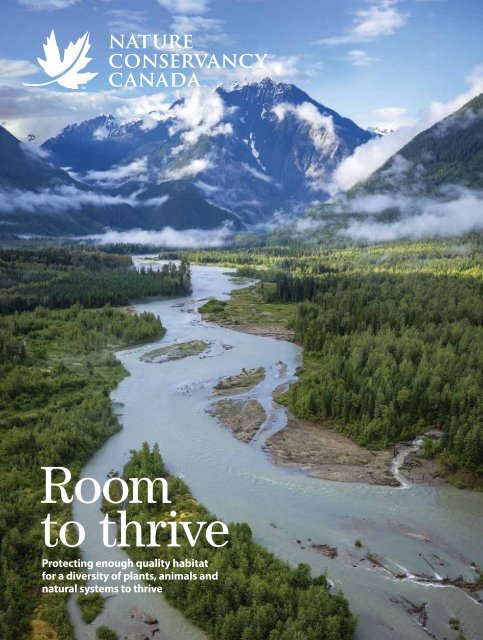

Room<br />

to thrive<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

Protecting enough quality habitat<br />

for a diversity of plants, animals and<br />

natural systems to thrive<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER 2021 1

WINTER <strong>2024</strong><br />

CONTENTS<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

4 Nature knows no bounds<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has partnered with Parks Canada to<br />

bolster conservation near national parks.<br />

6 Ghost Horse Hills<br />

Embrace the frosty magic of the season<br />

with a captivating hike in this winter<br />

playground north of Edmonton.<br />

7 <strong>Winter</strong>’s avian<br />

allure unveiled<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> is a great time to learn the<br />

basics of birding.<br />

7 Dream catcher<br />

Colin Campbell’s backpack carries the<br />

memories of his family’s connection to<br />

nature, and to each other.<br />

8 Room to thrive<br />

Protecting appropriate habitat in<br />

adequate amounts is essential<br />

to providing connected landscapes<br />

that support biodiversity.<br />

12 Mule deer<br />

This member of the Cervidae family<br />

is named for its large, mule-like ears.<br />

14 Project updates<br />

Enhancing biodiversity in SK; advancing<br />

Reconciliation in MB; partnership<br />

with Qalipu First Nation; <strong>NCC</strong> on the<br />

world stage.<br />

16 Visual impact<br />

Photographer Mike Dembeck connects<br />

our hearts to nature through his images.<br />

18 Weaving nature into art<br />

Art inspired by nature, with the land and<br />

sustainability at its core.<br />

Digital extras<br />

Check out our online magazine page with<br />

additional content to supplement this issue,<br />

at nccmagazine.ca.<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

365 Bloor Street East, Suite 1501<br />

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4W 3L4<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca | Phone: 416.932.3202 | Toll-free: 877.231.3552<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is the country’s unifying force for nature. We seek<br />

solutions to the twin crises of rapid biodiversity loss and climate change through large-scale,<br />

permanent land conservation. <strong>NCC</strong> is a registered charity. With nature, we build a thriving world.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada.<br />

FSC® is not responsible for any calculations<br />

on saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed in Canada with vegetable-based inks by Warrens Waterless Printing.<br />

This publication saved 31 trees and 30,668 litres of water*.<br />

CREATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM. PHOTO: DENIS DUQUETTE. COVER: PAUL ZIZKA (INCOMAPPLEUX VALLEY, BC).<br />

*<br />

2 WINTER <strong>2024</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Musquash Estuary<br />

Nature Reserve, NB.<br />

Featured<br />

Contributors<br />

MARIE-MICHELE ROUSSEAU-CLAIR: ETIENNE BOISVERT.<br />

Dear friends,<br />

Being in nature provides me with a sense of harmony<br />

and wholeness; it’s part of what I need to thrive. In fact,<br />

I chose the city where I live based on its proximity to<br />

nature and protected areas, including La Mauricie National Park and<br />

adjacent Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) projects. I love to<br />

spend time in these places and reflect on how elements of the CARE<br />

principle (Connected, Adequate, Representative and Effective) are<br />

at work to make nature more resilient to the impacts of biodiversity<br />

loss and climate change.<br />

The national park, as you’ll learn on page 4, is also part of an<br />

exciting new partnership between Parks Canada and <strong>NCC</strong> to bolster<br />

conservation across the country. It contributes to providing suitable<br />

habitat for at-risk eastern wolves. In complement, <strong>NCC</strong>’s projects<br />

adjacent to the park protect habitat for wood turtles. Together, the<br />

area is made more resilient through the connectedness and variety<br />

of quality habitats, as well as knowledge sharing and collaboration<br />

between the two organizations.<br />

In this issue, we delve into the A of CARE in our four-part<br />

series: understanding the importance of protecting enough of<br />

every habitat for species, natural processes and cultural aspects<br />

to persist through time. As Iryn Tushabe explores in the feature<br />

story, adequacy goes hand in hand with connectivity to achieve<br />

a network of quality habitats for life to thrive.<br />

I hope you will be inspired by the examples of conservation in<br />

this issue that embrace adequacy and see the opportunities for<br />

more great work from coast to coast. Thank you for your continued<br />

support of Canada’s nature.<br />

Yours in conservation,<br />

Marie-Michele Rousseau-Clair<br />

Marie-Michele Rousseau-Clair<br />

Chief conservation officer<br />

Iryn Tushabe<br />

is a Ugandan-Canadian<br />

writer and journalist<br />

now living in Regina,<br />

Saskatchewan. Her work<br />

has been nominated for<br />

numerous awards. Her<br />

debut novel, Everything<br />

is Fine Here, is forthcoming<br />

with House of<br />

Anansi press in winter<br />

2025. She wrote “Room<br />

to thrive,” page 8.<br />

Aaron McKenzie<br />

Fraser is a professional<br />

editorial, commercial<br />

& industrial photographer<br />

based in<br />

Halifax. He specializes<br />

in location-based<br />

environmental<br />

portraits for magazines<br />

and advertising.<br />

Aaron photographed<br />

Mike Dembeck for<br />

“Visual impact,”<br />

page 16.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

2<br />

1<br />

Nature<br />

knows<br />

3<br />

4<br />

no bounds<br />

5<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has partnered with Parks Canada to<br />

bolster conservation near national parks<br />

6<br />

Birders’ paradise, picturesque summits, soul-soothing<br />

forests, seaside vistas and rolling prairies…Canada’s<br />

national parks and national park reserves teem with life.<br />

The survival of the plants and animals living in these natural<br />

enclaves, however, depends on connected and intact natural<br />

spaces beyond park borders. Yet the landscapes that bring us<br />

these gems are under threat from climate change and biodiversity<br />

loss, and strained by human activity and development.<br />

A new partnership between the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) and Parks Canada (PC) will support healthy and resilient<br />

landscapes across the country.<br />

The Landscape Resiliency Program, a $30-million initiative,<br />

was launched in October 2023. PC will contribute $15 million to<br />

the project, with <strong>NCC</strong> raising another $15 million. <strong>NCC</strong> will work<br />

with Indigenous Nations, local communities, property owners<br />

and partners to support area-based conservation near several<br />

PC parks or reserves. The goal is to conserve 30,000 hectares by<br />

2026. Explore these special places and the species they sustain.<br />

Learn more at natureconservancy.ca/resiliency.<br />

1. Gulf Islands<br />

National Park Reserve<br />

Nestled off Vancouver Island’s<br />

southeastern coast, the Gulf Islands<br />

National Park Reserve protects islets<br />

and coastal landscapes. Seals, otters,<br />

orcas and salmon swim in the waters<br />

of the Salish Sea, while seabirds and<br />

eagles fly above. <strong>NCC</strong> has supported<br />

conservation in the Gulf Islands since<br />

the 1980s. The Salish Sea Natural Area<br />

is crucial to the migration of many<br />

species, including at-risk western<br />

grebes. Most recently, <strong>NCC</strong> secured<br />

Reginald Hill on Salt Spring Island<br />

and Edith Point on Mayne Island, both<br />

of which protect significant stands of<br />

mature coastal Douglas-fir forest.<br />

2. Kootenay National Park<br />

British Columbia is a gift to nature<br />

lovers; the stunning landscapes here<br />

just keep on giving. And Kootenay<br />

National Park is no exception. This<br />

Rocky Mountain gem is a haven for<br />

diverse wildlife, like moose, grizzly<br />

bear, black bear and Canada lynx.<br />

Home to 29 endangered species, it<br />

features open forests and grasslands.<br />

Since the 1990s, <strong>NCC</strong>’s efforts in the<br />

area have enhanced connectivity and<br />

restored vital habitats, especially at<br />

Thunder Hill Ranch, Marion Creek<br />

Benchlands and Luxor Linkage.<br />

1: FERNANDO LESSA; 2: THOMAS DRASDAUSKIS; 3: BRENT CALVER; 4: JASON BANTLE;<br />

5: ADAM BIALO/KONTAKT FILMS; 6: BRIANNE CURRY/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

4 WINTER <strong>2024</strong> natureconservancy.ca

7: <strong>NCC</strong>; 8: <strong>NCC</strong>; 9: ANDREW HERYGERS/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; 10: MIKE DEMBECK.<br />

7<br />

8<br />

3. Waterton Lakes<br />

National Park<br />

The magic of Waterton Lakes<br />

National Park occurs where four<br />

unique ecosystems converge. Aptly<br />

named “nature’s meeting place,” it is<br />

a haven for diverse wildlife. Next to<br />

the park lies the Rocky Mountain<br />

Front region, where species like elk<br />

migrate between the mountains and<br />

the foothills grasslands. In 1997, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

and the Weston Family Foundation<br />

jointly launched the Waterton Park<br />

Front Project, a 12,950-hectare<br />

conservation initiative that changed<br />

the course of Canadian conservation<br />

by providing the template for<br />

multiple landscape-scale projects<br />

funded by the Foundation.<br />

9<br />

10<br />

4. Grasslands<br />

National Park<br />

Nature takes centre stage at<br />

Grasslands National Park in southwest<br />

Saskatchewan. Here, the province’s<br />

largest remaining tracts of native<br />

grasslands are home to iconic species<br />

like pronghorn, swift fox and<br />

ferruginous hawk. Visitors may spot<br />

at-risk loggerhead shrikes spearing<br />

their prey on thorns and spikes, or<br />

burrowing owls peeping up from<br />

badger holes. Thanks to more than<br />

25 years of community collaboration,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has protected vital natural areas<br />

like Old Man on His Back Prairie and<br />

Heritage Conservation Area, Wideview<br />

Complex and Rangeview for critters<br />

of all shapes and sizes to thrive.<br />

5. Bruce Peninsula<br />

National Park<br />

Bruce Peninsula National Park’s<br />

renowned aquamarine waters hug<br />

the Saugeen Bruce Peninsula and<br />

will have visitors wondering whether<br />

they’re in the Caribbean. The<br />

escarpment’s shoreline caves boast<br />

a bouquet of biodiversity, from<br />

gastropods to hibernating bats.<br />

While marvelling at the marshes,<br />

meadows, alvars and sandy shores,<br />

remember that this area supports<br />

globally rare species, including over<br />

50 species at risk. Since 2014, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

has worked alongside the Saugeen<br />

Ojibway Nation to ensure the<br />

peninsula continues to thrive for<br />

future generations by protecting<br />

habitats, monitoring species at risk,<br />

managing invasive species and more.<br />

6. Point Pelee<br />

National Park<br />

At the southern tip of mainland<br />

Canada lies Point Pelee National Park.<br />

The Carolinian Life Zone, which contains<br />

this tiny slice of Canada, supports<br />

2,200 plant species and over half of<br />

the country’s bird species. It’s also<br />

where rare snails hang out — the<br />

unsung heroes of nutrient recycling.<br />

But “outrunning” environmental<br />

threats for these snails would be quite<br />

the challenge. That’s why habitat<br />

protection is vital for their survival.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> and its partners have been<br />

working in the surrounding area since<br />

2000, protecting and enriching this<br />

unique haven, ensuring local species<br />

continue to thrive and work their<br />

ecological magic.<br />

7. Thousand Islands<br />

National Park<br />

Thousand Islands National Park<br />

features rugged shorelines and<br />

granite islands in the St. Lawrence<br />

River. Part of the Frontenac Arch<br />

natural area and snuggled between<br />

the Algonquin Highlands and the<br />

Adirondack Mountains, this park is<br />

part of a vital wildlife corridor and<br />

a meeting point for Carolinian and<br />

boreal species. The surrounding<br />

natural area boasts UNESCO and<br />

Canadian Herpetological Society<br />

designations and supports 40 species<br />

at risk, including Canada’s largest<br />

snake, gray ratsnake. <strong>NCC</strong>, Parks<br />

Canada and partners have collaborated<br />

in the Frontenac Arch since the<br />

early 2000s to conserve, restore and<br />

connect natural spaces here.<br />

8. La Mauricie<br />

National Park<br />

La Mauricie National Park, nestled<br />

in the Laurentian Mountains,<br />

boasts over 150 lakes and ponds and<br />

supports a multitude of unique<br />

species, including the vulnerable<br />

wood turtle. But quantity does not<br />

necessarily equal quality. Helping<br />

species like wood turtles requires<br />

quality habitat and connectivity.<br />

Ongoing conservation efforts to<br />

expand the area’s vital ecological<br />

corridors will ensure that turtles and<br />

other species can live, breed and<br />

thrive. In 2022, <strong>NCC</strong> protected two<br />

sites as part of an ecological corridor<br />

connecting La Mauricie National Park<br />

and other protected areas.<br />

9. Kouchibouguac<br />

National Park<br />

Nature unfolds its glory on the east<br />

coast of New Brunswick at Kouchibouguac<br />

National Park, a biodiverse<br />

tapestry of estuaries and salt marshes,<br />

freshwater, wetlands and forest ecosystems.<br />

Visitors can marvel at the tidal<br />

forces that sculpt the landscape here.<br />

More than 15 species at risk are found<br />

here and at nearby natural areas,<br />

including adorable, but endangered,<br />

piping plovers, which use the sandy<br />

beaches and mudflats for foraging<br />

and nesting. <strong>NCC</strong> has been working<br />

with partners and communities within<br />

25 kilometres of the park since 2009,<br />

with projects like the Cap-Lumière<br />

and Point Escuminac nature reserves.<br />

10. Kejimkujik<br />

National Park and<br />

National Historic Site<br />

Kejimkujik National Park and<br />

National Historic Site is within the<br />

greater natural area of southwest<br />

Nova Scotia. More than 2,800<br />

kilometres of shoreline, Wabanaki<br />

(Acadian) forests, barrens, wetlands<br />

and beach habitats provide a world<br />

of awe. But habitat loss and lack<br />

of connectivity are wreaking havoc<br />

on Nova Scotia’s eastern moose<br />

population. Protecting natural areas<br />

gives moose more room to roam<br />

and find food and shelter. Since 2002,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has conserved natural areas<br />

within 25 kilometres of the park, in<br />

collaboration with local communities<br />

and partners. Projects include the<br />

Silver River, Moose Lake and Upper<br />

Ohio nature reserves.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

<br />

N<br />

Ghost Horse Hills<br />

Range Road 234<br />

Township Road 584<br />

Ghost Horse Hills<br />

Embrace the frosty magic of the season with a captivating hike in this<br />

winter playground north of Edmonton<br />

Located just 55 kilometres north of Edmonton, this 110-hectare project features boreal<br />

forests and wetlands. It’s the perfect place to explore on a crisp winter’s day.<br />

As you embark on this snowy adventure, don’t forget to pack your snowshoes; this<br />

winter wonderland is often blanketed in a deep layer of snow.<br />

Ghost Horse Hills’ 800-metre path ends in a breathtaking view of the surrounding plains.<br />

This trail connects to a network of trails in the neighbouring Halfmoon Lake Natural Area for<br />

further winter wanderings.<br />

One of the most captivating features of Ghost Horse Hills is its boreal forest, where white<br />

spruce, white birch and jack pine trees tower above. Here, keep your eyes out for winter birds,<br />

such as pine grosbeak and bohemian waxwing. If you’re lucky, you might also spot snowshoe<br />

hare, porcupine or ermine tracks.1<br />

LEGEND<br />

-- Path<br />

P Parking<br />

SPECIES TO SPOT<br />

• American mink<br />

• bohemian waxwing<br />

• Canada jay<br />

• Canada lynx<br />

• common redpoll<br />

• ermine<br />

• least weasel<br />

• pine grosbeak<br />

• porcupine<br />

• snowshoe hare<br />

• snowy owl<br />

LEARN MORE<br />

Visit natureconservancy.ca/ghosthills<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; MICK THOMPSON; ROBERT MCCAW; DELANEY SCHLEMKO/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; MIRCEA COSTINA.<br />

6 WINTER <strong>2024</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

ACTIVITY<br />

CORNER<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

<strong>Winter</strong>’s avian<br />

allure unveiled<br />

Want to get to know more birds and birdsongs<br />

but don’t know where to start? <strong>Winter</strong> is a great<br />

time to learn the basics of birding. Bare branches<br />

give you a clearer sightline to see what’s flitting<br />

around, and with fewer species singing, zeroing<br />

in on a specific bird’s sound will be easier. Come<br />

spring and summer, you can build on that<br />

foundation of winter sights and noises and<br />

expand your repertoire as migratory species<br />

start to filter back. Here are some more tips<br />

for winter birding:<br />

PHOTO: LUCY LU. ILLUSTRATION: ISTOCK.<br />

ALL’S QUIET? DON’T FRET!<br />

<strong>Winter</strong> birding can feel a bit unrewarding at first.<br />

You may have to go quite some distance before<br />

picking up a chirp or tune. Turn your eyes and<br />

ears on high-alert mode and you’re more likely to<br />

pick something up. Look for dense, shrubby areas<br />

that could provide safe places to forage and shelter<br />

from the elements and predators. Watch for plants<br />

that retain fruits and seedheads and you may spot<br />

some feathery foragers.<br />

HEAD TO THE SHORELINE FOR WATERFOWL<br />

As ponds, lakes and rivers freeze up, waterfowl<br />

may congregate in denser flocks as the areas of<br />

open water get smaller and smaller. Fast-flowing<br />

water stays unfrozen for longer, and deeper ponds<br />

and lakes can be the last to freeze. In cold spells,<br />

birds not usually found in your area may show up<br />

if their normal wintering spots have frozen. It’s<br />

worth scanning your binoculars over every<br />

Canada goose and mallard in the flock in case<br />

there is a visitor among the crowd.<br />

KEEP YOUR FIELD GUIDE HANDY<br />

A good old-fashioned field guide with illustrations<br />

of the species and lookalikes is great to have.<br />

Apps like Merlin Bird ID can narrow down potential<br />

suspects with filters, such as colour, size, habitat<br />

and range. The sound ID feature can suggest which<br />

species is singing. You can also enter your observations<br />

into eBird to help the science and conservation<br />

community better understand the distribution<br />

patterns of our feathered friends.<br />

Dream catcher<br />

Colin Campbell’s backpack carries the memories of<br />

his family’s connection to nature, and to each other<br />

Our love for the outdoors, nurtured and enriched in the embrace of the<br />

temperate rainforest on Canada’s West Coast, has been made possible<br />

by a steadfast companion: a special backpack that has become the key<br />

to unlocking our wilderness dreams.<br />

This trusty backpack, weathered and well-loved, is a symbol of our collective journey.<br />

As my wife and I explored the winding trails of the Pacific Rim rainforest, we soon<br />

realized its invaluable role in our family’s adventures. With three young daughters in<br />

tow, the backpack has served as both a source of comfort and an emblem of possibility.<br />

One of its most remarkable features is the space it provides for our tired children.<br />

When their little legs can no longer carry them through the terrain, we gently hoist<br />

one of our daughters, typically the youngest one but not always, into the backpack,<br />

securing her snugly against our backs. Her sleepy smile tells us she is content,<br />

surrounded by the sounds of the forest and the scent of damp earth.<br />

The backpack is not just a means of transportation; it reminds me of nature. Its<br />

numerous pockets hold everything we need — a myriad of snacks and water bottles<br />

and trinkets.<br />

Our family’s bond continues to grow stronger with each excursion, as we meander<br />

through mossy groves, follow bubbling streams and marvel at giant cedars. The backpack<br />

bridges gap between generations, connecting us not only to the wilderness<br />

but to each other.1<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 7

Room<br />

to thrive<br />

Protecting appropriate habitat in adequate<br />

amounts is essential in providing connected<br />

landscapes that support biodiversity<br />

BY Iryn Tushabe<br />

natureconservancy.ca

Lonetree Lake, SK.<br />

GABE DIPPLE.<br />

Levi Boutin pulls a blade<br />

of grass from a thicket. Peeling<br />

back the narrow leaves to get<br />

at the even narrower panicle<br />

inside, he says, “So this part<br />

is the grass seed and then this twisted bit is<br />

the awn.” He’s holding it up, a tiny strip with<br />

the delicate appearance of a short needle<br />

and long thread. “When the seeds fall to the<br />

ground, and as other grasses or animals brush<br />

against it, it will just corkscrew into the<br />

ground, driving the seed into the soil.” This<br />

unique evolutionary strategy, the ability to<br />

self-seed, gives the prairie grass its name:<br />

needle-and-thread.<br />

The plant is one of many prairie species<br />

native to Saskatchewan’s grasslands, including<br />

here at Lonetree Lake, an hour and<br />

45 minutes south of Regina. It is so close to<br />

the U.S. border that my cellphone provider<br />

warns me about possible roaming charges.<br />

A brisk wind chops up the blue surface of<br />

the lake and noisily whips through the grass.<br />

But the herd of cattle grazing beyond the<br />

glittering water seems unperturbed. A large<br />

bird of prey hovers above us, possibly hunting<br />

for a mid-morning snack. Boutin, a stewardship<br />

coordinator with the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>), identifies it: ferruginous<br />

hawk. Looking around me, I can see at least<br />

two burrows in our immediate vicinity; ground<br />

squirrels abound. That hawk will not be hungry<br />

for long.<br />

Other at-risk birds that Boutin and others<br />

have seen here over the past year include<br />

chestnut-collared longspur, Sprague’s pipit,<br />

common nighthawk, horned grebe and western<br />

grebe.<br />

For the most part though, Lonetree Lake,<br />

also locally known as Clear Lake, is a stopover<br />

area for migrating birds.<br />

“In the spring, we were seeing upwards<br />

of 1,000 birds at one time,” says Boutin, adding<br />

that’s what makes this place even more<br />

special, since birds always need a place<br />

to refuel and catch some rest during their<br />

migration. “I like knowing that for thousands<br />

of birds, their first stop in Canada is this<br />

lake, and that now it will always be healthy<br />

and conserved.”<br />

Adequacy — having enough of every<br />

quality habitat for the persistence of biodiversity<br />

and natural processes — is one of<br />

the core CARE principles <strong>NCC</strong> relies upon<br />

when thinking about long-term conservation<br />

(see sidebar, page 11). It goes hand in hand<br />

with Representative, which is the inclusion,<br />

in the protected and conserved area network,<br />

of all the species and features that naturally<br />

exist there.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 9

“So, if you think of Saskatchewan, the first<br />

iconic image that probably comes to mind is<br />

prairies,” says Marie-Michele Rousseau-Clair,<br />

chief conservation officer for <strong>NCC</strong>. “But Saskatchewan<br />

is not only prairies. There are<br />

trees, water bodies — lakes and rivers — and<br />

tons of other amazing habitats. All of which<br />

are important for the survival of species.”<br />

The right mix<br />

Last summer, Saskatchewan residents pooled<br />

together their Saskatchewan Government<br />

Insurance rebates and donated the money to<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>. Funds from the Field of Dreams campaign,<br />

led by University of Regina professor<br />

Marc Spooner, and from other donors enabled<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> to acquire Lonetree Lake, a 629-hectare<br />

property that consists of native and tame<br />

grassland, seasonal creeks, wetlands and<br />

shoreline habitats. The diversity and quality<br />

of habitats in this one place make it possible<br />

to protect a whole host of native species that<br />

depend on these habitats to exist, including<br />

those facing the danger of extinction. “So, it’s<br />

the right hectare at the right place for the<br />

right reasons,” explains Rousseau-Clair.<br />

A health assessment of the grassland ecology<br />

showed patches of the land at Lonetree<br />

Lake to have been previously overgrazed,<br />

while others, like the area where the cows<br />

are grazing, hadn’t been disturbed much.<br />

“Our management plan is to rest the<br />

overgrazed area for a little while to allow<br />

for the recovery of the native grasses, which<br />

leads to better quality habitat,” Boutin says.<br />

“And we’re targeting grazing on the other<br />

side of the lake, which is thick with biomass.”<br />

Historically, at-risk species, such as burrowing<br />

owl, bobolink, great plains toad and<br />

eastern yellow-bellied racer, were observed<br />

at Lonetree Lake. It’s possible, Boutin says,<br />

that those species are still present, but they<br />

have yet to be spotted by <strong>NCC</strong> staff.<br />

“But that doesn’t really matter,” he says,<br />

explaining the strategy remains the same.<br />

“We will conserve this habitat with them in<br />

mind, knowing that they may very likely come<br />

back in search of food or a nesting place.”<br />

Needle-andthread<br />

grass.<br />

Burrowing owl.<br />

Complete care<br />

The Musquash Estuary Nature Reserve in<br />

New Brunswick is another example where<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is contributing to the goal of adequacy<br />

and connectivity, which is the C in CARE. Not<br />

only is it the organization’s largest reserve<br />

(2,300 protected hectares) in Atlantic Canada,<br />

it also connects a much larger provincial<br />

protected area, called Loch Alva, to the federal<br />

Musquash Estuary Marine Protected Area.<br />

“What we’ve done here is we’ve connected<br />

these two areas,” says Paula Noel, <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

New Brunswick program director. Previously,<br />

she explains, the upper waters of the river<br />

were protected, as was the marine component.<br />

But there was a gap in between that<br />

large mammals couldn’t navigate without the<br />

threat of going through industrial and developed<br />

areas. With that gap closed thanks to<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s acquisition of land parcels from different<br />

landowners, wildlife have a large tract of<br />

intact nature to themselves. The transition<br />

zone between land and water within the larger<br />

conservation area and estuary is a great<br />

example of both connectivity and adequacy.<br />

The combined area supports wide-ranging<br />

Moose.<br />

Musquash Estuary Nature Reserve, NB.<br />

mammals, such as moose, bear and bobcat,<br />

that depend on both aquatic and terrestrial<br />

habitat. These species require a variety of<br />

habitats, so by conserving the entire watershed<br />

from headwaters to coast, <strong>NCC</strong> is ensuring<br />

adequate space for these species to roam<br />

freely. “You can’t get much more complete<br />

than that,” says Noel, pointing to the entirety<br />

of the lands and waters conserved by the<br />

province, federal marine protected area,<br />

Ducks Unlimited Canada and <strong>NCC</strong> lands.<br />

Efforts continue to protect other quality<br />

habitat along the estuary, an important offshore<br />

marine environment and the only designated<br />

Marine Protected Area in the province.<br />

Having secured over 90 per cent of the land<br />

surrounding the estuary, Noel says <strong>NCC</strong> is<br />

expanding farther out along the coastline on<br />

the Bay of Fundy, where the tides are some<br />

of the highest in the world. “They bring in<br />

harbour seals and porpoises to feed on the<br />

rich marine life of fish and other invertebrates<br />

in the estuary,” she explains. “And then a lot<br />

of that production in the water gets exported<br />

offshore and helps support the fish and marine<br />

life in the Bay of Fundy.”<br />

L TO R: LEVI BOUTIN/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; ANDY TEUCHER; MIKE DEMBECK; COURTNEY CAMERON/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

10 WINTER <strong>2024</strong> natureconservancy.ca

L TO R: GABE DIPPLE; SEAN FEAGAN/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; LETA PEZDERIC/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

Nature’s rhythms<br />

Back at Lonetree Lake, we are making our<br />

way toward the top of the hill when Ross<br />

MacDonald arrives on the back of his gorgeous<br />

horse, Sun. An agrologist by profession<br />

with a specialization in grassland management,<br />

MacDonald is a rancher. He lives 24<br />

kilometres east of Lonetree Lake. They’re<br />

his cows grazing in the pastures south of the<br />

lake. As we approach the hill, he indicates<br />

a cow pie, calling it a manure pack.<br />

“There’s a whole system of biology that’s<br />

going on under here,” he says, turning the<br />

cow pie over to reveal a host of insect diversity<br />

underneath, including dung beetles. New<br />

plant growth is already integrated with the<br />

manure and will break it down over time, he<br />

explains, pulling nutrients into the ground.<br />

“And that’s really the fundamentals of building<br />

the soil,” he says.<br />

We continue our tour, the men telling me<br />

about these grasslands, how they have been<br />

here for tens of thousands of years, thriving<br />

under pulses of disturbance and rest. Historically,<br />

when buffalo roamed across North<br />

America, they were nourished by these pastures.<br />

The large, wild grazers were smart;<br />

they knew not to overgraze or damage the<br />

prairie. But cattle, buffalo’s replacement,<br />

aren’t as forward-thinking.<br />

“It’s our job to manipulate the cows, moving<br />

them where we need them to graze to<br />

achieve that pressure,” says MacDonald. This<br />

approach to habitat management reintroduces<br />

the pressure that the ecosystem evolved<br />

with, allowing for the prolific regrowth of<br />

native grasses, and facilitating habitats that<br />

are conducive for native species.<br />

Prairies offer habitat between their vegetation<br />

layers of midgrasses, shortgrasses, halfshrubs,<br />

wildflowers and ground cover. Most<br />

prairie birds are ground-nesting, so the quality<br />

of the vegetation is very important. Last<br />

year when Boutin first visited Lonetree Lake,<br />

he was impressed with the plant diversity<br />

even in the more exploited areas.<br />

“Here, let me show you,” Boutin says. He<br />

digs up a small clump of ground cover: the<br />

Lonetree Lake, SK.<br />

biocrust. Made up of clubmoss and lichen, it<br />

is green and spongy with a shallow network of<br />

roots that holds the dirt together, protecting<br />

the soil from blowing away with the wind<br />

or washing off in the rain. This fragile layer,<br />

which takes the longest to re-establish, is<br />

important for the grassland’s resilience.<br />

“When rain drops hit it, the spongy mass<br />

cushions the raindrop’s fall and then draws<br />

the moisture into the ground,” MacDonald<br />

says of biocrust, calling it a crucial species of<br />

grassland ecology that’s under-appreciated.<br />

“In its absence, the raindrop smashes the soil<br />

directly and erodes it.”<br />

The presence and extent of the biocrust<br />

indicates it won’t take more than the<br />

re-establishment of the natural rhythms of<br />

disturbance and rest to return the grassland<br />

habitat to its optimal health. In fact, one year<br />

under the stewardship of <strong>NCC</strong> and Lonetree<br />

Lake is already bouncing back: a patchwork<br />

of grass both grazed and ungrazed, shrubs,<br />

rocks and wildflowers. Beyond the fence,<br />

the land connects to neighbouring tracts of<br />

grassland reaching beyond the border into<br />

the U.S. It’s a fabric large enough to provide<br />

refuge for species escaping from human<br />

pressures, such as farming, on adjacent<br />

privately owned land.<br />

Climate change is another pressure whose<br />

inevitable impact on adequacy is hard to<br />

predict since different species respond differently.<br />

According to Rousseau-Clair, <strong>NCC</strong> is<br />

accessing data about how climate conditions<br />

will affect biodiversity now and in the future<br />

to anticipate and predict where current and<br />

future habitat refugia are located.<br />

“There’s a lot of research going on,” she<br />

says, explaining that in some cases, <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

own research program is addressing knowledge<br />

gaps. “There’s data for several species,<br />

habitat and processes, but data doesn’t exist<br />

for everything. We can benefit from more<br />

and better evidence to inform our work.”<br />

What remains unchanging is the need,<br />

she says, to provide connected habitats in<br />

a proportion that is connected, adequate,<br />

representative and effective.1<br />

C ARE<br />

It’s perhaps no surprise that at<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> we CARE about nature every<br />

day. You see, for nature to thrive,<br />

protected and conserved areas<br />

need to be Connected, have<br />

Adequate quality habitats, be<br />

Representative of all species and<br />

be managed Effectively. Together,<br />

those principles represent<br />

an internationally recognized<br />

framework to support the creation<br />

of resilient landscapes. If the<br />

places we conserve meet these<br />

criteria, landscapes will be able to<br />

withstand the impacts of climate<br />

change and biodiversity loss.<br />

And if they are resilient, then we<br />

feel confident we are building<br />

a thriving world with nature.<br />

What does adequate conservation<br />

look like? It means protected<br />

areas include enough quality<br />

habitat to allow a diversity of<br />

plants, animals and natural<br />

systems to survive. Has an<br />

adequate amount of area or<br />

habitat been secured for<br />

each feature or species of<br />

concern/interest? Some species<br />

need more habitat than others,<br />

and the goal is to protect enough<br />

habitat for each species to<br />

survive and ideally thrive into<br />

the future.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Mule<br />

deer<br />

Native to western North America, this<br />

member of the Cervidae family is named<br />

for its large, mule-like ears<br />

MARK RAYCROFT.<br />

12 WINTER <strong>2024</strong> natureconservancy.ca

APPEARANCE<br />

The most distinguishing features of<br />

mule deer are their large ears and white<br />

rump patch. They have a dark forehead<br />

and light grey face, and their small, white<br />

tail is tipped with black. Males typically<br />

weigh 65 to 110 kilograms, and females<br />

can weigh 50 to 75 kilograms. Their<br />

reddish-brown coat changes to<br />

a brownish-grey in winter.<br />

HABITAT<br />

This species thrives in<br />

habitats with early-stage plant<br />

growth, mixed plant species and<br />

shrubs. In BC, mule deer remain at<br />

high elevations until late fall and<br />

then migrate to lower ranges<br />

with shallower snow.<br />

What is <strong>NCC</strong> doing<br />

to protect habitat<br />

for this species?<br />

In BC, <strong>NCC</strong> protects deer<br />

habitat on its Kootenay River<br />

Ranch, Luxor Linkage, Sage<br />

and Sparrow and Bunchgrass<br />

Hills properties. In Alberta,<br />

mule deer have been observed<br />

on the Wakaluk, Palmer<br />

Ranch and Carbon Coulee<br />

properties. Connectivity to<br />

other large, protected areas,<br />

such as provincial parkland,<br />

is essential for this<br />

species’ survival.1<br />

THREATS<br />

Threats to this species include<br />

habitat loss and conversion, climate<br />

change and vehicle collisions where<br />

roads cross major winter ranges.<br />

Chronic wasting disease, a fatal<br />

degenerative disease, is a major<br />

threat to mule deer populations<br />

east of the Rockies.<br />

Kootenay River<br />

Ranch, BC.<br />

HELP<br />

OUT<br />

Help protect habitat<br />

for species at risk at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

donate.<br />

NICK NAULT.<br />

RANGE<br />

Mule deer, including black-tailed<br />

deer, are found only in North America;<br />

from northern Mexico to southeast Alaska<br />

and the southern Yukon, and from the Pacific<br />

Coast to western Manitoba, Kansas and<br />

northwest Texas. In Canada, most are found in<br />

the rugged, dry valleys and plateau of<br />

BC’s southern interior, while in Alberta, they<br />

are most common in the grasslands,<br />

foothills and Rocky Mountains, and in<br />

the parklands and southern<br />

boreal forest.<br />

•<br />

Range in Canada<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 13

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

Enhancing biodiversity at Echo Creek<br />

ECHO CREEK, SK<br />

1<br />

2<br />

4<br />

THANK YOU!<br />

Your support has made these<br />

projects possible. Learn more at<br />

natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work.<br />

3<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) plays a vital role in<br />

conserving biodiversity, often embarking on ecosystem restoration<br />

in areas it protects. Echo Creek in Saskatchewan is<br />

a prime example, where <strong>NCC</strong> is restoring idle croplands overrun by<br />

invasive weeds. Over two years, staff will combat these invaders<br />

through mowing and chemical control, followed by seeding native<br />

grasses and forbs.<br />

Erosion along the creek threatens further habitat loss and sedimentation.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is working to restore the area by rallying community<br />

volunteers and planting native shrubs and willow staking. As trees<br />

and shrubs take root, they'll stabilize banks, reduce runoff and lessen<br />

the risk of floods. A healthy streambank fosters diverse species, enhances<br />

landscape connectivity and corridors for wildlife movement,<br />

curbs erosion, filters contaminants, and boosts aquatic biodiversity<br />

now and for future generations.<br />

PORTRAIT: KYLIE POLLARD/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; <strong>NCC</strong>. INSET: MARLA ANDERSON/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

Rooted in<br />

the landscape<br />

“I am originally from Nova Scotia. I moved to<br />

Alberta in 1958 to be a teacher and have remained<br />

in Alberta where I eventually met my wife, Mary.<br />

“Even over the years, Nova Scotia has held a special<br />

place in my heart — particularly Port Joli, located<br />

in the southwest of the province. As a child, my<br />

family vacationed there during the summer. I have<br />

beautiful memories of my grandfather’s small,<br />

rustic cabin overlooking the white sandy beach.<br />

I remember wildlife all around the cabin, from<br />

shorebirds to moose.<br />

Cutting over croplands, Echo Creek, SK.<br />

Above: Seeding over croplands, Echo Creek, SK.<br />

“In the spring 2017 issue of the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong>, I learned that <strong>NCC</strong> was protecting<br />

lands in Port Joli. I was thrilled to know this<br />

place and the nature I grew up with will be there<br />

forever, even though the cabin is long gone. This<br />

is a place where I still have family roots. Although<br />

I never lived in the area, it is still like going home<br />

when I have a chance to visit.<br />

“If my grandfather were alive today, I am sure he<br />

would be a dedicated and enthusiastic supporter<br />

of the Nature Conservancy of Canada. As I am,<br />

he would be immensely proud that my home<br />

province’s beautiful and vibrant Port Joli region<br />

will be protected for posterity.”<br />

~Cal and Mary Annis have been <strong>NCC</strong><br />

donors since 1991<br />

14 WINTER 2023 natureconservancy.ca

Cattle at Jackson Pipestone, SK<br />

FAYAZ HASAN/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF; MATT GASNER/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

2 Advancing<br />

3<br />

Reconciliation<br />

WAGGLE SPRINGS, MB<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is working with local Anishinaabe representatives<br />

and the Beddome family to jointly steward<br />

and monitor 305 hectares on the banks of the Assiniboine<br />

River, south of Shilo. This area is important<br />

culturally, agriculturally and for biodiversity<br />

conservation. The land, near Waggle Springs, has<br />

been named Wabano Aki, which translates to<br />

“Tomorrows Land” in Anishinaabemowin.<br />

This partnership serves as inspiration to advance<br />

Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and<br />

is an example of how conservation success can be<br />

achieved through a whole-of-society approach.<br />

To learn more visit natureconservancy.ca/wabanoaki.<br />

4<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> on the world stage<br />

PLANET EARTH<br />

Naming ceremony at Wabano Aki, MB.<br />

A unique internship<br />

experience<br />

QALIPU FIRST NATION<br />

Last summer Julia Ball, a graduate of Memorial<br />

University of Newfoundland, joined <strong>NCC</strong> as a<br />

conservation intern. As the first shared intern<br />

between <strong>NCC</strong> and partner organization Qalipu<br />

First Nation (QFN), Ball became a key conduit<br />

between the two organizations.<br />

The ongoing partnership with QFN involves<br />

information sharing and remote stewardship support.<br />

Ball brought to the shared internship role a<br />

keen interest to learn from Indigenous knowledge<br />

and a passion for nature. As an intern hosted in<br />

QFN’s office, she was <strong>NCC</strong>’s boots on the ground<br />

for the west coast of the island.<br />

The knowledge gained, relationships made and<br />

friendships forged during this internship have<br />

provided Ball with a great foundation to embark<br />

on her professional career; she now works fulltime<br />

with QFN. This unique internship was made<br />

possible by the generous support of our funder,<br />

Cenovus Energy.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is making sure nature’s voice is heard and respected, each time the world gathers to find solutions<br />

to the climate and biodiversity crises. Whether at a climate conference of the parties (COP) or one<br />

focused on biodiversity, <strong>NCC</strong> helps show the world how enduring and impactful conservation initiatives<br />

can help tackle these monumental challenges.<br />

For example, leading up to the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in December 2022, <strong>NCC</strong><br />

worked alongside other Canadian delegates and international leaders to identify how the world could<br />

reach its conservation goals by 2030. Then, after the world adopted a new framework for nature at<br />

that conference, <strong>NCC</strong> stepped forward to help Canada achieve its conservation targets. And, at the<br />

latest climate conference last December in Dubai (COP28), <strong>NCC</strong> highlighted the economic value that<br />

protecting and restoring nature can bring to communities. We’re not done, either.<br />

This October, <strong>NCC</strong> will host global peers in conservation at the <strong>2024</strong> Global Congress of the<br />

International Land Conservation Network in Mont-Sainte-Anne, QC. Together, <strong>NCC</strong> and these groups<br />

are finding bigger, bolder and more inclusive ways to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, and combat<br />

the impacts of climate change, all achieved through nature conservation.<br />

To conserve the planet’s biodiversity and safeguard our communities from the impacts of climate<br />

change, nature conservation needs to be a priority. <strong>NCC</strong> is helping ensure it is.1<br />

Partner Spotlight<br />

Grasslands are important for soil<br />

and water conservation, flood<br />

control and climate regulation.<br />

Sometimes described as an<br />

upside-down forest, grasslands<br />

absorb and store billions of tonnes<br />

of carbon in their deep roots,<br />

keeping it fixed in the soil and<br />

helping to counter the effects of<br />

climate change. They are also one<br />

of the world’s most endangered<br />

ecosystems, and over 80 per cent<br />

of Canada's Prairie grasslands have<br />

already been lost. <strong>NCC</strong>’s Prairie<br />

Grasslands Action Plan is leading<br />

efforts to conserve more than<br />

500,000 hectares by 2030.<br />

In 2023, Wawanesa Insurance<br />

partnered with <strong>NCC</strong> to support<br />

two interns in Manitoba working<br />

to conserve Canada’s grasslands.<br />

Wawanesa’s partnership meant<br />

supporting interns working on<br />

the ground and collecting critical<br />

data that informs land stewardship<br />

and restoration practices, in an<br />

effort to conserve priority areas,<br />

like grasslands, today and for<br />

future generations.<br />

Wawanesa sees climate resiliency<br />

as a growing need in every<br />

community. That is why, as a<br />

Canadian-owned and operated<br />

mutual insurance company, they<br />

are supporting people on the<br />

front lines of climate change who<br />

are working to build more resilient<br />

communities through their new<br />

Wawanesa Climate Champions<br />

program. In addition to serving<br />

over 1.6 million members across<br />

Canada, the company invests over<br />

$3.5 million annually to support<br />

organizations that strengthen<br />

Canadian communities, with a focus<br />

on supporting organizations on the<br />

front lines of climate change.<br />

For more information, visit<br />

wawanesa.com/community-impact.<br />

natureconservancy.ca

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Visual<br />

impact<br />

Mike Dembeck connects<br />

our hearts to nature through<br />

his images of Canadian<br />

landscapes and the species<br />

that rely on them<br />

AARON MCKENZIE FRASER.<br />

16 WINTER <strong>2024</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Gazing across the expansive grassland<br />

landscape, Mike Dembeck observed<br />

the large herd of bison in front of him.<br />

It was calving season and newborns, with<br />

their fuzzy, light-brown coats, bleated while their<br />

mothers grunted and kept a watchful eye.<br />

MIKE DEMBECK.<br />

The stamps of the bison hooves sent a cloud of dust into the air. Dembeck<br />

remembers a strong, musky smell. He was enveloped by a symphony of<br />

animal noises, as he looked through his camera and clicked the shutter.<br />

It was 2016 and Dembeck was photographing the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>)’s Buffalo Valley property in southern Saskatchewan.<br />

He felt part of something unique.<br />

“Seeing the connection between these animals, it was an emotional<br />

moment, a storytelling moment,” says Dembeck. “Those are the times to<br />

capture something that people can relate to.”<br />

Dembeck often thinks about the emotional response to the photos and<br />

videos he creates. For the past 16 years, he has gifted his time and talent<br />

to <strong>NCC</strong> as a photographer and videographer, showing landscapes and<br />

species across the country. The East Coast features heavily in his work,<br />

as he is based in Halifax.<br />

Growing up with an interest in photography, Dembeck started out at<br />

a Halifax newspaper after university. From there, his career continued on<br />

to other news organizations and freelancing.<br />

In 2007, Dembeck was covering an <strong>NCC</strong> press conference featuring<br />

animals from a nearby wildlife rehabilitation clinic. While the cute<br />

animals caught his attention, he says the idea of collaborating with<br />

a national conservation organization captured his imagination.<br />

“I remember thinking this was a chance to work in the big leagues,<br />

making an impact for the environment,” he says. Since then, Dembeck’s<br />

stunning visuals of wildlife, habitat and people on the land have been an<br />

invaluable gift to <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Bringing awareness to wider audiences is a driving force behind<br />

Dembeck’s work. “People don’t realize what is out there, what is being<br />

lost,” he says.<br />

PATIENCE REQUIRED<br />

Few people see animals like Canada lynx, moose and wolves in the wild.<br />

Dembeck’s visuals of species like these over the years remind him of<br />

time spent, the effort and payoff.<br />

“When you do get a chance to take that picture you’re looking for, it<br />

is so rewarding,” he says. “I think about how it will connect with people<br />

who usually never get to see that animal.”<br />

To photograph a creature as elusive as Canada lynx, planning and tenacity<br />

are required. Dembeck consults local experts and sets up in a position<br />

that respects the animal’s space and is not threatening. “Animals are<br />

so aware; if you’re in their environment, they are probably already paying<br />

attention to you,” he says. “You need patience.”<br />

In some cases, he’s left empty-handed or spends multiple days returning<br />

to the same area. Dembeck also deals with pesky insects and<br />

challenging weather while he patiently waits. These excursions are always<br />

worth it, though. “It’s made me visit all of these different places, walk<br />

through the woods and really pay attention,” he adds.<br />

As a repeat visitor to many <strong>NCC</strong> projects, Dembeck sees the benefits<br />

of conservation and stewardship. “You can see in an area, because it’s<br />

been nurtured and protected, that it has stabilized,” he says.<br />

“Sometimes, in the area nearby, you can see<br />

a contrast, that it has been hurt or been prevented<br />

from healing.”<br />

Dembeck has developed a special relationship<br />

with staff on the ground at <strong>NCC</strong> through<br />

his longstanding volunteer work. “Conservation<br />

work is a collaborative effort,” he says, reflecting<br />

on the success of places like Buffalo Valley.<br />

“It’s invigorating to be able to contribute.”<br />

The bison Dembeck photographed are part<br />

of a managed herd of livestock that grazes the<br />

Prairie grasslands at Buffalo Valley. At over<br />

1,600 hectares, it is part of the Missouri Coteau<br />

Natural Area and provides habitat for songbirds,<br />

waterfowl, deer and many other species.<br />

Closer to home than the rolling plains of<br />

Saskatchewan, Dembeck has canoed and photographed<br />

the Tusket River in southern Nova Scotia.<br />

It’s linked to the Silver River Nature Reserve,<br />

and he feels a special connection to the area.<br />

“You’re there on the ground floor when<br />

it [a conservation project] comes together, so<br />

you get emotionally invested,” says Dembeck of<br />

the conservation work along the Tusket River.<br />

“Seeing a project succeed is deeply rewarding.<br />

These projects are like our kids.”<br />

Dembeck is committed to his conservation<br />

involvement. “It’s become fundamental to me as<br />

a person,” he says. “The amount that I get back<br />

is exponentially greater than what I produce.”1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

WINTER <strong>2024</strong> 17

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Weaving nature into art<br />

By Raechel Wastesicoot, <strong>NCC</strong>’s manager, internal communications & culture<br />

When I close my eyes, I’m on the land. I can<br />

hear the wind wrestle its way through thickets<br />

of dense trees, their leaves resting on<br />

the snow blanketing the ground I am walking on. The sun<br />

pierces its way through cottony clouds, adorning a sky so<br />

blue, it looks almost painted. Sunbeams light up a pathway<br />

through a forest bursting with colours from plants and the<br />

small critters that stay awake during the winter months.<br />

I can see it so clearly, almost feeling winter’s cold prickling<br />

my skin as I close the invisible mental diary in my mind.<br />

When I open my eyes, I’m at my work desk — a mess<br />

of beads, leather, fur and antler scattered in front of me.<br />

Where some may see chaos, I see nature. I see the chlorophyll<br />

swirling across the table in the form of glass and<br />

dyed porcupine quills. There’s a rush of water as soft,<br />

white fur from rabbits and blue beads scatter across<br />

my beading mat. My thread is strung, rich with colours<br />

reminiscent of what I see when I’m out in nature.<br />

My work follows a teaching passed down to me<br />

when I first learned how to bead: from the land, for the<br />

land and by the land. Informed by that teaching, my<br />

work is composed of a mix of contemporary pieces with<br />

upcycled, vintage and harvested materials. With the<br />

land and sustainability at the centre of my approach to<br />

beadwork, the pieces I create aim to have minimal impact<br />

on the environment. Vintage, found and natural<br />

materials that are gifts from the land, such as antlers,<br />

fur, hides and porcupine quills, are instrumental in how<br />

my work comes together.<br />

I find inspiration in nature. As an Indigenous person,<br />

who I am, the land my ancestors come from, the language<br />

we speak and our community is grounded within<br />

Mother Earth. I take this with me when I’m out in nature,<br />

surrounded by everything the land has given us,<br />

and when I’m at home, beading at my weathered wooden<br />

desk.1<br />

BEADWORK AND PHOTO: RAECHEL WASTESICOOT/<strong>NCC</strong> STAFF.<br />

18 WINTER <strong>2024</strong> natureconservancy.ca

LET YOUR<br />

PASSION<br />

DEFINE<br />

YOUR<br />

LEGACY<br />

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can define<br />

your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy of Canada,<br />

no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable habitats and the<br />

wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for generations to come.<br />

Order your Free Legacy Information Booklet today!<br />

Call Jackie at 1-877-231-3552 x2275 or visit DefineYourLegacy.ca

YOUR<br />

IMPACT<br />

Sustaining<br />

species and<br />

community<br />

The Stoco Karst Forest property<br />

near Napanee, Ontario, has now<br />

been protected, thanks to your<br />

support. This 81-hectare property<br />

contains forests, wetlands and<br />

karst — a network of limestone<br />

caves and crevices beneath the<br />

surface. These features provide<br />

flood regulation and water purification<br />

services for downstream<br />

communities. This project creates<br />

a buffer for nearby Stoco Fen<br />

Provincial Park, a 350-hectare<br />

nature reserve class park. Together,<br />

protected lands in the Stoco<br />

Fen area sustain wide-ranging<br />

species such as black bear,<br />

moose and bobcat, which require<br />

large expanses of habitat.<br />

ELI DRUMMOND; <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Biodiversity<br />

protected<br />

in Quebec<br />

Thanks to your support, 200<br />

hectares of Baie-Saint-Paul’s<br />

flats and beaches in the<br />

St. Lawrence Estuary have<br />

been protected. The lands<br />

are recognized for both their<br />

cultural and natural beauty,<br />

attracting thousands of<br />

visitors each year, and are<br />

significant for aquatic birds<br />

and several at-risk species.<br />

We will work hand in hand<br />

with the city of Baie-Saint-Paul<br />

to conserve its fragile<br />

ecosystems and protect the<br />

region’s long-term biodiversity.<br />

Thank you for all you do for nature in Canada!