The Salopian Summer 2023

v2

v2

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SCHOOL NEWS 23<br />

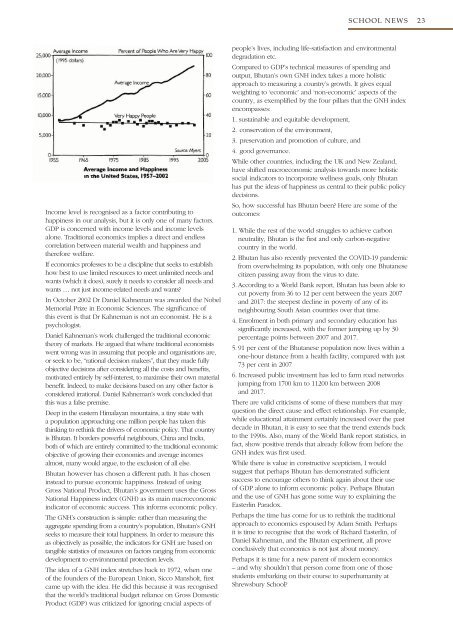

Income level is recognised as a factor contributing to<br />

happiness in our analysis, but it is only one of many factors.<br />

GDP is concerned with income levels and income levels<br />

alone. Traditional economics implies a direct and endless<br />

correlation between material wealth and happiness and<br />

therefore welfare.<br />

If economics professes to be a discipline that seeks to establish<br />

how best to use limited resources to meet unlimited needs and<br />

wants (which it does), surely it needs to consider all needs and<br />

wants … not just income-related needs and wants?<br />

In October 2002 Dr Daniel Kahneman was awarded the Nobel<br />

Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. <strong>The</strong> significance of<br />

this event is that Dr Kahneman is not an economist. He is a<br />

psychologist.<br />

Daniel Kahneman’s work challenged the traditional economic<br />

theory of markets. He argued that where traditional economists<br />

went wrong was in assuming that people and organisations are,<br />

or seek to be, “rational decision makers”, that they made fully<br />

objective decisions after considering all the costs and benefits,<br />

motivated entirely by self-interest, to maximise their own material<br />

benefit. Indeed, to make decisions based on any other factor is<br />

considered irrational. Daniel Kahneman’s work concluded that<br />

this was a false premise.<br />

Deep in the eastern Himalayan mountains, a tiny state with<br />

a population approaching one million people has taken this<br />

thinking to rethink the drivers of economic policy. That country<br />

is Bhutan. It borders powerful neighbours, China and India,<br />

both of which are entirely committed to the traditional economic<br />

objective of growing their economies and average incomes<br />

almost, many would argue, to the exclusion of all else.<br />

Bhutan however has chosen a different path. It has chosen<br />

instead to pursue economic happiness. Instead of using<br />

Gross National Product, Bhutan’s government uses the Gross<br />

National Happiness index (GNH) as its main macroeconomic<br />

indicator of economic success. This informs economic policy.<br />

<strong>The</strong> GNH’s construction is simple: rather than measuring the<br />

aggregate spending from a country’s population, Bhutan’s GNH<br />

seeks to measure their total happiness. In order to measure this<br />

as objectively as possible, the indicators for GNH are based on<br />

tangible statistics of measures on factors ranging from economic<br />

development to environmental protection levels.<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea of a GNH index stretches back to 1972, when one<br />

of the founders of the European Union, Sicco Mansholt, first<br />

came up with the idea. He did this because it was recognised<br />

that the world’s traditional budget reliance on Gross Domestic<br />

Product (GDP) was criticized for ignoring crucial aspects of<br />

people’s lives, including life-satisfaction and environmental<br />

degradation etc.<br />

Compared to GDP’s technical measures of spending and<br />

output, Bhutan’s own GNH index takes a more holistic<br />

approach to measuring a country’s growth. It gives equal<br />

weighting to ‘economic’ and ‘non-economic’ aspects of the<br />

country, as exemplified by the four pillars that the GNH index<br />

encompasses:<br />

1. sustainable and equitable development,<br />

2. conservation of the environment,<br />

3. preservation and promotion of culture, and<br />

4. good governance.<br />

While other countries, including the UK and New Zealand,<br />

have shifted macroeconomic analysis towards more holistic<br />

social indicators to incorporate wellness goals, only Bhutan<br />

has put the ideas of happiness as central to their public policy<br />

decisions.<br />

So, how successful has Bhutan been? Here are some of the<br />

outcomes:<br />

1. While the rest of the world struggles to achieve carbon<br />

neutrality, Bhutan is the first and only carbon-negative<br />

country in the world.<br />

2. Bhutan has also recently prevented the COVID-19 pandemic<br />

from overwhelming its population, with only one Bhutanese<br />

citizen passing away from the virus to date.<br />

3. According to a World Bank report, Bhutan has been able to<br />

cut poverty from 36 to 12 per cent between the years 2007<br />

and 2017: the steepest decline in poverty of any of its<br />

neighbouring South Asian countries over that time.<br />

4. Enrolment in both primary and secondary education has<br />

significantly increased, with the former jumping up by 30<br />

percentage points between 2007 and 2017.<br />

5. 91 per cent of the Bhutanese population now lives within a<br />

one-hour distance from a health facility, compared with just<br />

73 per cent in 2007<br />

6. Increased public investment has led to farm road networks<br />

jumping from 1700 km to 11200 km between 2008<br />

and 2017.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are valid criticisms of some of these numbers that may<br />

question the direct cause and effect relationship. For example,<br />

while educational attainment certainly increased over the past<br />

decade in Bhutan, it is easy to see that the trend extends back<br />

to the 1990s. Also, many of the World Bank report statistics, in<br />

fact, show positive trends that already follow from before the<br />

GNH index was first used.<br />

While there is value in constructive scepticism, I would<br />

suggest that perhaps Bhutan has demonstrated sufficient<br />

success to encourage others to think again about their use<br />

of GDP alone to inform economic policy. Perhaps Bhutan<br />

and the use of GNH has gone some way to explaining the<br />

Easterlin Paradox.<br />

Perhaps the time has come for us to rethink the traditional<br />

approach to economics espoused by Adam Smith. Perhaps<br />

it is time to recognise that the work of Richard Easterlin, of<br />

Daniel Kahneman, and the Bhutan experiment, all prove<br />

conclusively that economics is not just about money.<br />

Perhaps it is time for a new parent of modern economics<br />

– and why shouldn’t that person come from one of those<br />

students embarking on their course to superhumanity at<br />

Shrewsbury School?