einstein

einstein

einstein

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

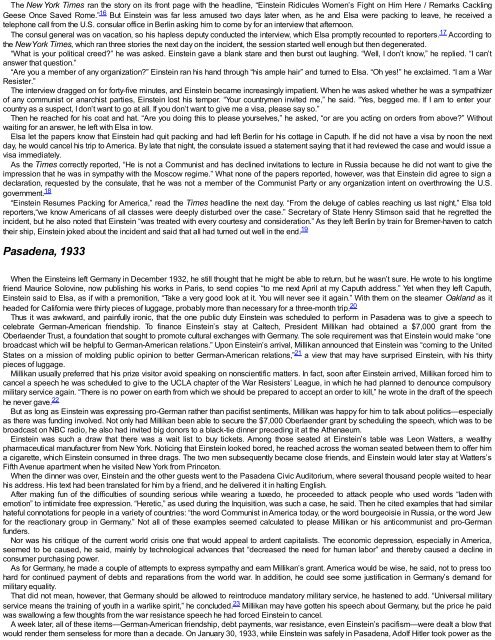

The New York Times ran the story on its front page with the headline, “Einstein Ridicules Women’s Fight on Him Here / Remarks Cackling<br />

Geese Once Saved Rome.” 16 But Einstein was far less amused two days later when, as he and Elsa were packing to leave, he received a<br />

telephone call from the U.S. consular office in Berlin asking him to come by for an interview that afternoon.<br />

The consul general was on vacation, so his hapless deputy conducted the interview, which Elsa promptly recounted to reporters. 17 According to<br />

the New York Times, which ran three stories the next day on the incident, the session started well enough but then degenerated.<br />

“What is your political creed?” he was asked. Einstein gave a blank stare and then burst out laughing. “Well, I don’t know,” he replied. “I can’t<br />

answer that question.”<br />

“Are you a member of any organization?” Einstein ran his hand through “his ample hair” and turned to Elsa. “Oh yes!” he exclaimed. “I am a War<br />

Resister.”<br />

The interview dragged on for forty-five minutes, and Einstein became increasingly impatient. When he was asked whether he was a sympathizer<br />

of any communist or anarchist parties, Einstein lost his temper. “Your countrymen invited me,” he said. “Yes, begged me. If I am to enter your<br />

country as a suspect, I don’t want to go at all. If you don’t want to give me a visa, please say so.”<br />

Then he reached for his coat and hat. “Are you doing this to please yourselves,” he asked, “or are you acting on orders from above?” Without<br />

waiting for an answer, he left with Elsa in tow.<br />

Elsa let the papers know that Einstein had quit packing and had left Berlin for his cottage in Caputh. If he did not have a visa by noon the next<br />

day, he would cancel his trip to America. By late that night, the consulate issued a statement saying that it had reviewed the case and would issue a<br />

visa immediately.<br />

As the Times correctly reported, “He is not a Communist and has declined invitations to lecture in Russia because he did not want to give the<br />

impression that he was in sympathy with the Moscow regime.” What none of the papers reported, however, was that Einstein did agree to sign a<br />

declaration, requested by the consulate, that he was not a member of the Communist Party or any organization intent on overthrowing the U.S.<br />

government. 18<br />

“Einstein Resumes Packing for America,” read the Times headline the next day. “From the deluge of cables reaching us last night,” Elsa told<br />

reporters,“we know Americans of all classes were deeply disturbed over the case.” Secretary of State Henry Stimson said that he regretted the<br />

incident, but he also noted that Einstein “was treated with every courtesy and consideration.” As they left Berlin by train for Bremer-haven to catch<br />

their ship, Einstein joked about the incident and said that all had turned out well in the end. 19<br />

Pasadena, 1933<br />

When the Einsteins left Germany in December 1932, he still thought that he might be able to return, but he wasn’t sure. He wrote to his longtime<br />

friend Maurice Solovine, now publishing his works in Paris, to send copies “to me next April at my Caputh address.” Yet when they left Caputh,<br />

Einstein said to Elsa, as if with a premonition, “Take a very good look at it. You will never see it again.” With them on the steamer Oakland as it<br />

headed for California were thirty pieces of luggage, probably more than necessary for a three-month trip. 20<br />

Thus it was awkward, and painfully ironic, that the one public duty Einstein was scheduled to perform in Pasadena was to give a speech to<br />

celebrate German-American friendship. To finance Einstein’s stay at Caltech, President Millikan had obtained a $7,000 grant from the<br />

Oberlaender Trust, a foundation that sought to promote cultural exchanges with Germany. The sole requirement was that Einstein would make “one<br />

broadcast which will be helpful to German-American relations.” Upon Einstein’s arrival, Millikan announced that Einstein was “coming to the United<br />

States on a mission of molding public opinion to better German-American relations,” 21 a view that may have surprised Einstein, with his thirty<br />

pieces of luggage.<br />

Millikan usually preferred that his prize visitor avoid speaking on nonscientific matters. In fact, soon after Einstein arrived, Millikan forced him to<br />

cancel a speech he was scheduled to give to the UCLA chapter of the War Resisters’ League, in which he had planned to denounce compulsory<br />

military service again. “There is no power on earth from which we should be prepared to accept an order to kill,” he wrote in the draft of the speech<br />

he never gave. 22<br />

But as long as Einstein was expressing pro-German rather than pacifist sentiments, Millikan was happy for him to talk about politics—especially<br />

as there was funding involved. Not only had Millikan been able to secure the $7,000 Oberlaender grant by scheduling the speech, which was to be<br />

broadcast on NBC radio, he also had invited big donors to a black-tie dinner preceding it at the Athenaeum.<br />

Einstein was such a draw that there was a wait list to buy tickets. Among those seated at Einstein’s table was Leon Watters, a wealthy<br />

pharmaceutical manufacturer from New York. Noticing that Einstein looked bored, he reached across the woman seated between them to offer him<br />

a cigarette, which Einstein consumed in three drags. The two men subsequently became close friends, and Einstein would later stay at Watters’s<br />

Fifth Avenue apartment when he visited New York from Princeton.<br />

When the dinner was over, Einstein and the other guests went to the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, where several thousand people waited to hear<br />

his address. His text had been translated for him by a friend, and he delivered it in halting English.<br />

After making fun of the difficulties of sounding serious while wearing a tuxedo, he proceeded to attack people who used words “laden with<br />

emotion” to intimidate free expression. “Heretic,” as used during the Inquisition, was such a case, he said. Then he cited examples that had similar<br />

hateful connotations for people in a variety of countries: “the word Communist in America today, or the word bourgeoisie in Russia, or the word Jew<br />

for the reactionary group in Germany.” Not all of these examples seemed calculated to please Millikan or his anticommunist and pro-German<br />

funders.<br />

Nor was his critique of the current world crisis one that would appeal to ardent capitalists. The economic depression, especially in America,<br />

seemed to be caused, he said, mainly by technological advances that “decreased the need for human labor” and thereby caused a decline in<br />

consumer purchasing power.<br />

As for Germany, he made a couple of attempts to express sympathy and earn Millikan’s grant. America would be wise, he said, not to press too<br />

hard for continued payment of debts and reparations from the world war. In addition, he could see some justification in Germany’s demand for<br />

military equality.<br />

That did not mean, however, that Germany should be allowed to reintroduce mandatory military service, he hastened to add. “Universal military<br />

service means the training of youth in a warlike spirit,” he concluded. 23 Millikan may have gotten his speech about Germany, but the price he paid<br />

was swallowing a few thoughts from the war resistance speech he had forced Einstein to cancel.<br />

A week later, all of these items—German-American friendship, debt payments, war resistance, even Einstein’s pacifism—were dealt a blow that<br />

would render them senseless for more than a decade. On January 30, 1933, while Einstein was safely in Pasadena, Adolf Hitler took power as the