einstein

einstein

einstein

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

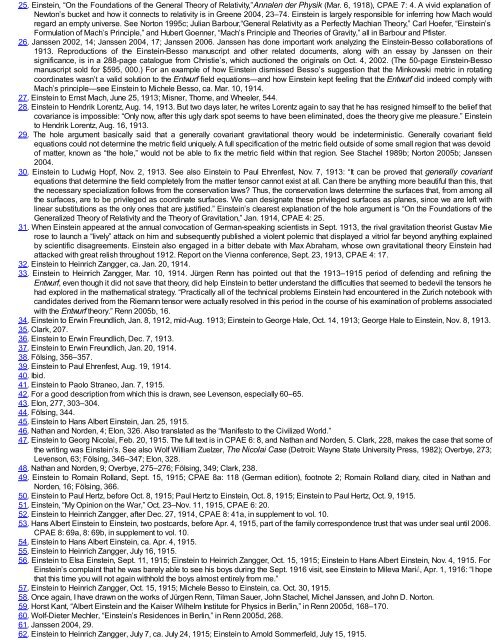

25. Einstein, “On the Foundations of the General Theory of Relativity,”Annalen der Physik (Mar. 6, 1918), CPAE 7: 4. A vivid explanation of<br />

Newton’s bucket and how it connects to relativity is in Greene 2004, 23–74. Einstein is largely responsible for inferring how Mach would<br />

regard an empty universe. See Norton 1995c; Julian Barbour,“General Relativity as a Perfectly Machian Theory,” Carl Hoefer, “Einstein’s<br />

Formulation of Mach’s Principle,” and Hubert Goenner, “Mach’s Principle and Theories of Gravity,” all in Barbour and Pfister.<br />

26. Janssen 2002, 14; Janssen 2004, 17; Janssen 2006. Janssen has done important work analyzing the Einstein-Besso collaborations of<br />

1913. Reproductions of the Einstein-Besso manuscript and other related documents, along with an essay by Janssen on their<br />

significance, is in a 288-page catalogue from Christie’s, which auctioned the originals on Oct. 4, 2002. (The 50-page Einstein-Besso<br />

manuscript sold for $595, 000.) For an example of how Einstein dismissed Besso’s suggestion that the Minkowski metric in rotating<br />

coordinates wasn’t a valid solution to the Entwurf field equations—and how Einstein kept feeling that the Entwurf did indeed comply with<br />

Mach’s principle—see Einstein to Michele Besso, ca. Mar. 10, 1914.<br />

27. Einstein to Ernst Mach, June 25, 1913; Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, 544.<br />

28. Einstein to Hendrik Lorentz, Aug. 14, 1913. But two days later, he writes Lorentz again to say that he has resigned himself to the belief that<br />

covariance is impossible: “Only now, after this ugly dark spot seems to have been eliminated, does the theory give me pleasure.” Einstein<br />

to Hendrik Lorentz, Aug. 16, 1913.<br />

29. The hole argument basically said that a generally covariant gravitational theory would be indeterministic. Generally covariant field<br />

equations could not determine the metric field uniquely. A full specification of the metric field outside of some small region that was devoid<br />

of matter, known as “the hole,” would not be able to fix the metric field within that region. See Stachel 1989b; Norton 2005b; Janssen<br />

2004.<br />

30. Einstein to Ludwig Hopf, Nov. 2, 1913. See also Einstein to Paul Ehrenfest, Nov. 7, 1913: “It can be proved that generally covariant<br />

equations that determine the field completely from the matter tensor cannot exist at all. Can there be anything more beautiful than this, that<br />

the necessary specialization follows from the conservation laws? Thus, the conservation laws determine the surfaces that, from among all<br />

the surfaces, are to be privileged as coordinate surfaces. We can designate these privileged surfaces as planes, since we are left with<br />

linear substitutions as the only ones that are justified.” Einstein’s clearest explanation of the hole argument is “On the Foundations of the<br />

Generalized Theory of Relativity and the Theory of Gravitation,” Jan. 1914, CPAE 4: 25.<br />

31. When Einstein appeared at the annual convocation of German-speaking scientists in Sept. 1913, the rival gravitation theorist Gustav Mie<br />

rose to launch a “lively” attack on him and subsequently published a violent polemic that displayed a vitriol far beyond anything explained<br />

by scientific disagreements. Einstein also engaged in a bitter debate with Max Abraham, whose own gravitational theory Einstein had<br />

attacked with great relish throughout 1912. Report on the Vienna conference, Sept. 23, 1913, CPAE 4: 17.<br />

32. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, ca. Jan. 20, 1914.<br />

33. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, Mar. 10, 1914. Jürgen Renn has pointed out that the 1913–1915 period of defending and refining the<br />

Entwurf, even though it did not save that theory, did help Einstein to better understand the difficulties that seemed to bedevil the tensors he<br />

had explored in the mathematical strategy. “Practically all of the technical problems Einstein had encountered in the Zurich notebook with<br />

candidates derived from the Riemann tensor were actually resolved in this period in the course of his examination of problems associated<br />

with the Entwurf theory.” Renn 2005b, 16.<br />

34. Einstein to Erwin Freundlich, Jan. 8, 1912, mid-Aug. 1913; Einstein to George Hale, Oct. 14, 1913; George Hale to Einstein, Nov. 8, 1913.<br />

35. Clark, 207.<br />

36. Einstein to Erwin Freundlich, Dec. 7, 1913.<br />

37. Einstein to Erwin Freundlich, Jan. 20, 1914.<br />

38. Fölsing, 356–357.<br />

39. Einstein to Paul Ehrenfest, Aug. 19, 1914.<br />

40. Ibid.<br />

41. Einstein to Paolo Straneo, Jan. 7, 1915.<br />

42. For a good description from which this is drawn, see Levenson, especially 60–65.<br />

43. Elon, 277, 303–304.<br />

44. Fölsing, 344.<br />

45. Einstein to Hans Albert Einstein, Jan. 25, 1915.<br />

46. Nathan and Norden, 4; Elon, 326. Also translated as the “Manifesto to the Civilized World.”<br />

47. Einstein to Georg Nicolai, Feb. 20, 1915. The full text is in CPAE 6: 8, and Nathan and Norden, 5. Clark, 228, makes the case that some of<br />

the writing was Einstein’s. See also Wolf William Zuelzer, The Nicolai Case (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1982); Overbye, 273;<br />

Levenson, 63; Fölsing, 346–347; Elon, 328.<br />

48. Nathan and Norden, 9; Overbye, 275–276; Fölsing, 349; Clark, 238.<br />

49. Einstein to Romain Rolland, Sept. 15, 1915; CPAE 8a: 118 (German edition), footnote 2; Romain Rolland diary, cited in Nathan and<br />

Norden, 16; Fölsing, 366.<br />

50. Einstein to Paul Hertz, before Oct. 8, 1915; Paul Hertz to Einstein, Oct. 8, 1915; Einstein to Paul Hertz, Oct. 9, 1915.<br />

51. Einstein, “My Opinion on the War,” Oct. 23–Nov. 11, 1915, CPAE 6: 20.<br />

52. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, after Dec. 27, 1914, CPAE 8: 41a, in supplement to vol. 10.<br />

53. Hans Albert Einstein to Einstein, two postcards, before Apr. 4, 1915, part of the family correspondence trust that was under seal until 2006.<br />

CPAE 8: 69a, 8: 69b, in supplement to vol. 10.<br />

54. Einstein to Hans Albert Einstein, ca. Apr. 4, 1915.<br />

55. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, July 16, 1915.<br />

56. Einstein to Elsa Einstein, Sept. 11, 1915; Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, Oct. 15, 1915; Einstein to Hans Albert Einstein, Nov. 4, 1915. For<br />

Einstein’s complaint that he was barely able to see his boys during the Sept. 1916 visit, see Einstein to Mileva Mari , Apr. 1, 1916: “I hope<br />

that this time you will not again withhold the boys almost entirely from me.”<br />

57. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, Oct. 15, 1915; Michele Besso to Einstein, ca. Oct. 30, 1915.<br />

58. Once again, I have drawn on the works of Jürgen Renn, Tilman Sauer, John Stachel, Michel Janssen, and John D. Norton.<br />

59. Horst Kant, “Albert Einstein and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin,” in Renn 2005d, 168–170.<br />

60. Wolf-Dieter Mechler, “Einstein’s Residences in Berlin,” in Renn 2005d, 268.<br />

61. Janssen 2004, 29.<br />

62. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, July 7, ca. July 24, 1915; Einstein to Arnold Sommerfeld, July 15, 1915.