OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF SCOTLAND - The Journal Online

OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF SCOTLAND - The Journal Online

OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF SCOTLAND - The Journal Online

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

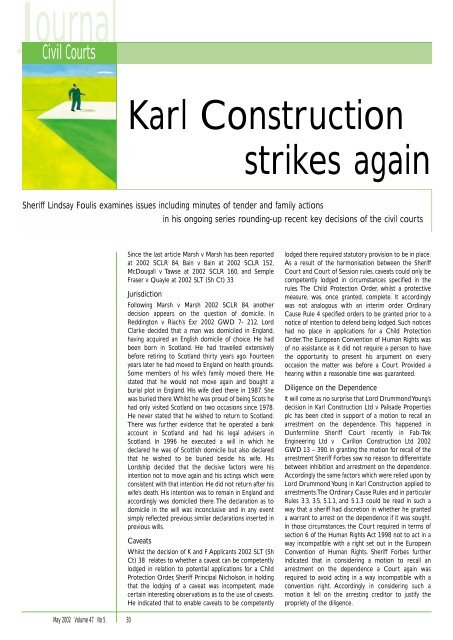

<strong>Journal</strong><br />

Civil Courts<br />

May 2002 Volume 47 No 5 30<br />

Karl Construction<br />

strikes again<br />

Sheriff Lindsay Foulis examines issues including minutes of tender and family actions<br />

in his ongoing series rounding-up recent key decisions of the civil courts<br />

Since the last article Marsh v Marsh has been reported<br />

at 2002 SCLR 84, Bain v Bain at 2002 SCLR 152,<br />

McDougall v Tawse at 2002 SCLR 160, and Semple<br />

Fraser v Quayle at 2002 SLT (Sh Ct) 33<br />

Jurisdiction<br />

Following Marsh v Marsh 2002 SCLR 84, another<br />

decision appears on the question of domicile. In<br />

Reddington v Riach’s Exr 2002 GWD 7- 212, Lord<br />

Clarke decided that a man was domiciled in England,<br />

having acquired an English domicile of choice. He had<br />

been born in Scotland. He had travelled extensively<br />

before retiring to Scotland thirty years ago. Fourteen<br />

years later he had moved to England on health grounds.<br />

Some members of his wife’s family moved there. He<br />

stated that he would not move again and bought a<br />

burial plot in England. His wife died there in 1987. She<br />

was buried there.Whilst he was proud of being Scots he<br />

had only visited Scotland on two occasions since 1978.<br />

He never stated that he wished to return to Scotland.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was further evidence that he operated a bank<br />

account in Scotland and had his legal advisers in<br />

Scotland. In 1996 he executed a will in which he<br />

declared he was of Scottish domicile but also declared<br />

that he wished to be buried beside his wife. His<br />

Lordship decided that the decisive factors were his<br />

intention not to move again and his actings which were<br />

consistent with that intention. He did not return after his<br />

wife’s death. His intention was to remain in England and<br />

accordingly was domiciled there. <strong>The</strong> declaration as to<br />

domicile in the will was inconclusive and in any event<br />

simply reflected previous similar declarations inserted in<br />

previous wills.<br />

Caveats<br />

Whilst the decision of K and F Applicants 2002 SLT (Sh<br />

Ct) 38 relates to whether a caveat can be competently<br />

lodged in relation to potential applications for a Child<br />

Protection Order, Sheriff Principal Nicholson, in holding<br />

that the lodging of a caveat was incompetent, made<br />

certain interesting observations as to the use of caveats.<br />

He indicated that to enable caveats to be competently<br />

lodged there required statutory provision to be in place.<br />

As a result of the harmonisation between the Sheriff<br />

Court and Court of Session rules, caveats could only be<br />

competently lodged in circumstances specified in the<br />

rules. <strong>The</strong> Child Protection Order, whilst a protective<br />

measure, was, once granted, complete. It accordingly<br />

was not analogous with an interim order. Ordinary<br />

Cause Rule 4 specified orders to be granted prior to a<br />

notice of intention to defend being lodged. Such notices<br />

had no place in applications for a Child Protection<br />

Order.<strong>The</strong> European Convention of Human Rights was<br />

of no assistance as it did not require a person to have<br />

the opportunity to present his argument on every<br />

occasion the matter was before a Court. Provided a<br />

hearing within a reasonable time was guaranteed.<br />

Diligence on the Dependence<br />

It will come as no surprise that Lord Drummond Young’s<br />

decision in Karl Construction Ltd v Palisade Properties<br />

plc has been cited in support of a motion to recall an<br />

arrestment on the dependence. This happened in<br />

Dunfermline Sheriff Court recently in Fab-Tek<br />

Engineering Ltd v Carillon Construction Ltd 2002<br />

GWD 13 – 390. In granting the motion for recall of the<br />

arrestment Sheriff Forbes saw no reason to differentiate<br />

between inhibition and arrestment on the dependence.<br />

Accordingly the same factors which were relied upon by<br />

Lord Drummond Young in Karl Construction applied to<br />

arrestments.<strong>The</strong> Ordinary Cause Rules and in particular<br />

Rules 3.3, 3.5, 5.1.1, and 5.1.3 could be read in such a<br />

way that a sheriff had discretion in whether he granted<br />

a warrant to arrest on the dependence if it was sought.<br />

In those circumstances, the Court required in terms of<br />

section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998 not to act in a<br />

way incompatible with a right set out in the European<br />

Convention of Human Rights. Sheriff Forbes further<br />

indicated that in considering a motion to recall an<br />

arrestment on the dependence a Court again was<br />

required to avoid acting in a way incompatible with a<br />

convention right. Accordingly in considering such a<br />

motion it fell on the arresting creditor to justify the<br />

propriety of the diligence.