Dall'immagine al modello Note sulla cartografia geometrica in Italia ...

Dall'immagine al modello Note sulla cartografia geometrica in Italia ...

Dall'immagine al modello Note sulla cartografia geometrica in Italia ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

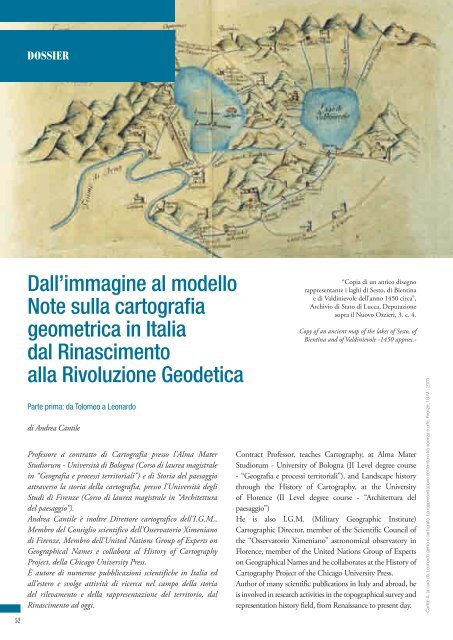

DOSSIER52D<strong>al</strong>l’immag<strong>in</strong>e <strong>al</strong> <strong>modello</strong><strong>Note</strong> <strong>sulla</strong> <strong>cartografia</strong><strong>geometrica</strong> <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>iad<strong>al</strong> R<strong>in</strong>ascimento<strong>al</strong>la Rivoluzione GeodeticaParte prima: da Tolomeo a Leonardodi Andrea CantileProfessore a contratto di Cartografia presso l'Alma MaterStudiorum - Università di Bologna (Corso di laurea magistr<strong>al</strong>e<strong>in</strong> “Geografia e processi territori<strong>al</strong>i”) e di Storia del paesaggioattraverso la storia della <strong>cartografia</strong>, presso l'Università degliStudi di Firenze (Corso di laurea magistr<strong>al</strong>e <strong>in</strong> “Architetturadel paesaggio”).Andrea Cantile è <strong>in</strong>oltre Direttore cartografico dell'I.G.M.,Membro del Consiglio scientifico dell'Osservatorio Ximenianodi Firenze, Membro dell'United Nations Group of Experts onGeographic<strong>al</strong> Names e collabora <strong>al</strong> History of CartographyProject, della Chicago University Press.È autore di numerose pubblicazioni scientifiche <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>ia ed<strong>al</strong>l’estero e svolge attività di ricerca nel campo della storiadel rilevamento e della rappresentazione del territorio, d<strong>al</strong>R<strong>in</strong>ascimento ad oggi.“Copia di un antico disegnorappresentante i laghi di Sesto, di Bient<strong>in</strong>ae di V<strong>al</strong>d<strong>in</strong>ievole dell'anno 1450 circa”,Archivio di Stato di Lucca, Deputazionesopra il Nuovo Ozzieri, 3. c. 4.Copy of an ancient map of the lakes of Sesto, ofBient<strong>in</strong>a and of V<strong>al</strong>d<strong>in</strong>ievole -1450 approx.-Contract Professor, teaches Cartography, at Alma MaterStudiorum - University of Bologna (II Level degree course- “Geografia e processi territori<strong>al</strong>i”), and Landscape historythrough the History of Cartography, at the Universityof Florence (II Level degree course - “Architettura delpaesaggio”)He is <strong>al</strong>so I.G.M. (Military Geographic Institute)Cartographic Director, member of the Scientific Council ofthe “Osservatorio Ximeniano” astronomic<strong>al</strong> observatory <strong>in</strong>Florence, member of the United Nations Group of Expertson Geographic<strong>al</strong> Names and he collaborates at the History ofCartography Project of the Chicago University Press.Author of many scientific publications <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y and abroad, heis <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> research activities <strong>in</strong> the topographic<strong>al</strong> survey andrepresentation history field, from Renaissance to present day.Cantile A. (a cura di), Leonardo genio e cartografo. La rappresentazione del territorio tra scienza e arte, Firenze, I.G.M., 2003

La genesi del lungo e complesso passaggio, che d<strong>al</strong>le anticheimmag<strong>in</strong>i descrittive dello spazio geografico ha condotto<strong>in</strong> epoca moderna <strong>al</strong>la modellizzazione di quest'ultimo si faris<strong>al</strong>ire norm<strong>al</strong>mente <strong>al</strong> XVIII secolo (<strong>al</strong>l'epoca cioè dellacosiddetta "Rivoluzione geodetica"), ma ha <strong>in</strong> re<strong>al</strong>tà le sueradici si trovano <strong>in</strong> epoche ben più remote, quando si posero lebasi per le def<strong>in</strong>izione degli elementi fondativi di quelle teorie edi quelle procedure operative su cui si basano ancora oggi tuttele attività di rilevamento e di rappresentazione del territorio.Le radici di questa rivoluzionaria trasformazione del mododi misurare, di rappresentare, ma soprattutto di percepire edi “leggere” il territorio si possono far ris<strong>al</strong>ire tra la f<strong>in</strong>e delMedioevo e gli <strong>in</strong>izi del R<strong>in</strong>ascimento, con una serie di eventiThe long and complicated process that comes from the oldgraphic descriptions of a geographic space to the moderngeometric cartography, set the fundaments of <strong>al</strong>l theoriesand operation<strong>al</strong> procedures that are still the ground of everyactivity concern<strong>in</strong>g the survey<strong>in</strong>g and the land representation.The start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t of the whole development is usu<strong>al</strong>ly placed<strong>in</strong> the XVIII century, at the time of the so-c<strong>al</strong>led “GeodeticRevolution”, but its orig<strong>in</strong> goes up to far earlier times.This change <strong>in</strong> the way to measure, to represent and, most ofTolomeo, Immag<strong>in</strong>e tratta d<strong>al</strong> frontespiziodi un volume del XVI secoloClaudius Ptolemaeus, Picture of XVI century book frontispiecehttp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Claudio_Tolomeo53

Questo crescente <strong>in</strong>teresse verso l’opera di Tolomeo sp<strong>in</strong>geIacopo Angeli da Scarperia, <strong>al</strong>lievo di Crisolora, a re<strong>al</strong>izzareuna versione <strong>in</strong> lat<strong>in</strong>o del codice del maestro, e poi FrancescoLapacc<strong>in</strong>i e Domenico Bon<strong>in</strong>segni ad elaborare delle copiedell’opera con la toponomastica <strong>in</strong>teramente tradotta <strong>in</strong>lat<strong>in</strong>o per rendere tot<strong>al</strong>mente accessibile la Geographia diTolomeo agli studiosi ed ai curiosi del tempo, affrancandocosì def<strong>in</strong>itivamente l’opera da quel millenario oblio etrasformandola <strong>in</strong> un vero e proprio best seller cartografico.La Geographia diviene negli anni a seguire un’operamonument<strong>al</strong>e, re<strong>al</strong>izzata con materi<strong>al</strong>i di vaglio, spessoimpreziosita con fatture di pregio e raff<strong>in</strong>ate decorazioni <strong>in</strong>oro, ed entra a far parte delle biblioteche dei più celebri epotenti personaggi del tempo, come P<strong>al</strong>la Strozzi, Lorenzo de’Medici, Federico da Montefeltro, Alfonso d’Aragona, Borsod’Este, Papa Gregorio XII, oltre che di numerosi studiosi ederuditi.La crescente diffusione della Geographia orig<strong>in</strong>a qu<strong>in</strong>di unaricca attività editori<strong>al</strong>e, che fa di Firenze il primo centrodi produzione di atlanti tolemaici di varie fatture e che siespande <strong>in</strong> <strong>al</strong>tre città d’Europa, conducendo <strong>al</strong>la nascitadi un florido mercato cartografico, anche a fogli sciolti,The fi rst one (chronologic<strong>al</strong>ly and for its relevance) it’s therenewed consideration of the Ptolemaic Geography <strong>in</strong> theWestern Countries. While such a theory had been neglectedfor <strong>al</strong>most a thousand years <strong>in</strong> Europe, through the Greek<strong>in</strong>heritance it had been enriched and cont<strong>in</strong>ued by the Islamicculture <strong>in</strong> the Middle East.Florence, 1397: this re-discovery beg<strong>in</strong>s with the com<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>totown of the Byzant<strong>in</strong>e Humanist Emmanuel Chrysoloras.He had been asked to teach Greek <strong>in</strong> the famous Studio bythe notorious man of letters and Chancellor of Florent<strong>in</strong>eRepublic, Coluccio S<strong>al</strong>utati.Together with Chrysoloras, <strong>al</strong>so a Greek copy of the Geographiaby Ptolemy with <strong>al</strong>l its maps arrived <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y. It was used, withothers codes belong<strong>in</strong>g to Chrysoloras himself, for the teach<strong>in</strong>gactivity <strong>in</strong> the Studio.The code was immediately recognised as a cornerstone. Throughit, for the fi rst time, the students of the Studio could be able tosee “<strong>in</strong> pictura” <strong>al</strong>l the places <strong>al</strong>ways mentioned <strong>in</strong> the classics:nouns of towns, mounts, rivers, countries and peoples.The Florent<strong>in</strong>e Studio acted as a sort of “sound box” for awider audience <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> know<strong>in</strong>g the world through thesight of Ptolemy. Quite soon, after the academic success, cameUna carta stampata del XV secolo raffigurante la descrizione di Tolomeo dell’Ecumene (1482, Johannes Schnitzer, <strong>in</strong>cisore)A pr<strong>in</strong>ted map from the XV century depict<strong>in</strong>g Ptolemy's description of the Oecumene (1482, Johannes Schnitzer, engraver)http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecumene55

ANNO I | n. 6 | NOVEMBRE - DICEMBRE 2009<strong>al</strong>imentato dagli <strong>in</strong>teressi di numerosi cultori e collezionisti.La tecnica c<strong>al</strong>cografica da stampa, poi, amplifica ancor più ilfenomeno, registrando come precursore il celebre stampatorefrancese, Anto<strong>in</strong>e Lafréry, attivo a Roma nella seconda metàdel C<strong>in</strong>quecento, che re<strong>al</strong>izza le prime Tavole Moderne diGeografia de la Maggior parte del Mondo di diversi avtoriraccolte et messe secondo l'ord<strong>in</strong>e di Tolomeo con i disegni dimolte citta et fortezze di diverse prov<strong>in</strong>tie stampate <strong>in</strong> rame constvdio et diligenza <strong>in</strong> Roma.Al di là degli aspetti economici, che pur svolgono un ruolo nonsecondario nella vicenda, l’elemento di maggior importanzaè costituito d<strong>al</strong>l’apertura di nuovi orizzonti cultur<strong>al</strong>i, provadell’esistenza di un humus nel qu<strong>al</strong>e germoglia appunto il“R<strong>in</strong>ascimento cartografico” it<strong>al</strong>iano e si pongono le basi perle successive conquiste <strong>in</strong> questo campo.Di converso, però, c’è anche da sottol<strong>in</strong>eare come il r<strong>in</strong>novatosuccesso di Tolomeo porti <strong>al</strong>cuni spiriti sedentari a riteneresufficiente lo studio della sua Geographia per la scopertadel mondo o, come diremmo oggi, per l’effettuazione diviaggi virtu<strong>al</strong>i, come efficacemente testimoniano le rime diLudovico Ariosto nella Satira III, dedicata a messer Annib<strong>al</strong>eM<strong>al</strong>aguzzi, del 1518 (vedi pag<strong>in</strong>a a fianco).Mentre le biblioteche dei potenti e degli eruditi si arricchisconocon le sofisticate del<strong>in</strong>eazioni cartografiche dei nuovi atlantitolemaici, la rappresentazione dello spazio geograficoper le f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>ità pratiche - legate ai diritti di proprietà o disfruttamento di risorse natur<strong>al</strong>i, <strong>al</strong>le regimazioni idrauliche,<strong>al</strong>le liti giudiziarie, a questioni conf<strong>in</strong>arie tra privati o tracomunità, <strong>al</strong>l’accensione di servitù su fondi agricoli, suboschi, su specchi d’acqua - resta però ancora ferma a formedi tipo descrittivo, con del<strong>in</strong>eazioni grafiche t<strong>al</strong>volta così naifda apparire oggi molto simili a disegni <strong>in</strong>fantili.Per avere un’idea di quanto elementari siano <strong>in</strong> t<strong>al</strong>e periodole rappresentazioni del territorio non di tipo tolemaico bastafare riferimento, a titolo esemplificativo, a due carte toscanedel Quattrocento e cioè la “Copia di un antico disegnorappresentante i laghi di Sesto, di Bient<strong>in</strong>a e di V<strong>al</strong>d<strong>in</strong>ievoledell’anno 1450 circa” (vedi pag<strong>in</strong>a 52) e la “Carta trovatanell’Archivio dei Monaci Cass<strong>in</strong>ensi di S. Flora e Lucilla diArezzo” sempre del medesimo periodo.La prima fornisce, senza <strong>al</strong>cun riguardo per la componentemetrica, <strong>in</strong>dicazioni sugli abitati, <strong>sulla</strong> viabilità, sull’idrografia,sull’orografia, con la relativa toponomastica, e la seconda,an<strong>al</strong>ogamente priva di ogni rapporto geometrico col vero,fornisce <strong>in</strong>formazioni <strong>in</strong> merito agli <strong>in</strong>sediamenti, <strong>al</strong>le stradeed ai ponti, ai corsi ed agli specchi d’acqua navigabili, <strong>al</strong>l’usodel suolo, con i vari nomi di luogo e delle strade.La lezione fondament<strong>al</strong>e impartita da Tolomeo, circa lemod<strong>al</strong>ità di sviluppo di una porzione di superficie sfericasul piano, per il tramite delle proiezioni e di opportunecoord<strong>in</strong>ate geografiche, non viene cioè subito assimilata daicartografi del tempo, determ<strong>in</strong>ando di fatto un’evidentediscrepanza tra le nuove rappresentazioni geografiche eTiziano,presunto ritratto di LudovicoAriostoTizian,portrait of a man, long believedto be Ludovico Ariosto56

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Ludovico_Ariosto“Chi vuol andar a torno, a torno vada:vegga Inghilterra, Ongheria, Francia e Spagna;a me piace abitar la mia contrada.Visto ho Toscana, Lombardia, Romagna;quel monte che divide e quel che serraIt<strong>al</strong>ia, e un mare e l’<strong>al</strong>tro che bagna.Questo mi basta; il resto de la terra,senza mai pagar l’oste, andrò cercandocon Ptolomeo, sia il mondo <strong>in</strong> pace o <strong>in</strong> guerra;e tutto il mar, senza far voti quandolampeggi il ciel, sicuro <strong>in</strong> su le carteverrò, più che sui legni, volteggiando.”In peace at home permitted to rema<strong>in</strong>Who goes and whither gives me little pa<strong>in</strong>Two seas that wash the It<strong>al</strong>ian coast I’ve seenAnd traversed over the land that lies betweenOf Apenn<strong>in</strong>es and Alps can t<strong>al</strong>k besideThat these enclose the country those divideNow idleness or prudence deems it bestIn maps and charts secure to view the restMy curious eyes here range from coast to coastThey need no passport and they pay no post.”

ANNO I | n. 6 | NOVEMBRE - DICEMBRE 2009corografiche di tipo tolemaico e quelle topografiche, nellequ<strong>al</strong>i ultime l’imitazione resiste <strong>al</strong>la regola <strong>geometrica</strong>.Anche se Iacopo Angeli da Scarperia ben evidenzia, neltesto <strong>in</strong>troduttivo della sua traduzione d<strong>al</strong> greco <strong>al</strong> lat<strong>in</strong>odella Geographia di Tolomeo, la portata rivoluzionariadell’opera dell’<strong>al</strong>essandr<strong>in</strong>o, consistente nella dimostrazionedel metodo per del<strong>in</strong>eare sul piano la sfera, conservando la“proportio cuiusque partis ad univers<strong>al</strong>e”, solo dopo <strong>al</strong>cunianni, nell’humus cultur<strong>al</strong>e della r<strong>in</strong>ascenza, germoglianonuovi <strong>in</strong>teressi di tipo cartografico anche tra i tecnici, dandoorig<strong>in</strong>e ad un nuovo filone di studi, d<strong>al</strong> qu<strong>al</strong>e deriva una riccatrattatistica <strong>in</strong> campo topografico.Capofila di questa nuova generazione di studiosi è LeonBattista Alberti, che recupera il precedente sapere mediev<strong>al</strong>eed il contributo della Geographia di Tolomeo per nuoveteorizzazioni e nuovi metodi <strong>in</strong> campo topografico ecartografico.Due scritti m<strong>in</strong>ori di Alberti hanno <strong>in</strong> particolare ilmerito di aver posto la prima pietra per la modellizzazionecartografica <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>ia: Ex ludis rerum mathematicarum, portatoa compimento prima del 1450, e Descriptio urbis Romae,re<strong>al</strong>izzato tra il 1443 ed il 1455. Vari <strong>al</strong>tri riferimenti di<strong>in</strong>teresse si riscontrano anche nel De Pictura, nel De Statua enel De re aedificatoria.Il primo di questi saggi contiene tra l’<strong>al</strong>tro una sorta diprontuario di topografia ante litteram. In esso, nel recuperareparte della lunga tradizione manu<strong>al</strong>istica ispirata <strong>al</strong>lageometria di Euclide, Alberti raccoglie i pr<strong>in</strong>cip<strong>al</strong>i artificimatematici, capaci di dare risposta a problemi di misura,apparentemente privi di soluzione e risolubili solo conmetodologie di determ<strong>in</strong>azione <strong>in</strong>diretta e di c<strong>al</strong>colo.I metodi proposti per la misura <strong>in</strong>diretta delle distanze sonorisolti con l’uso gener<strong>al</strong>izzato del primo criterio di similitud<strong>in</strong>efra triangoli rettangoli e con la cosiddetta “regola del tre”,mentre il contributo più importante dell’opera si riscontranel nuovo metodo di rilevamento topografico, che propone larisoluzione dei problemi di posizionamento relativo <strong>al</strong>la sc<strong>al</strong>aurbana, attraverso operazioni di triangolazione, già anticipatoper<strong>al</strong>tro da Giovanni Fontana nel suo Tractatus de trigonob<strong>al</strong>istario abbreviatus [...], del 1440, successivamente ripresoed ampliato da vari trattatisti r<strong>in</strong>asciment<strong>al</strong>i e perfezionatoulteriormente per <strong>al</strong>tri c<strong>in</strong>que secoli, f<strong>in</strong>o ai nostri giorni.Lo strumento impiegato per la triangolazione è ungoniometro, diviso <strong>in</strong> 48 parti, ancora privo di <strong>al</strong>idada e dibussola per l’orientamento <strong>al</strong> Nord magnetico, ed impiegato<strong>in</strong> abb<strong>in</strong>amento con un filo a piombo.Il metodo dell’Alberti viene illustrato <strong>in</strong> modo completo,spiegando prelim<strong>in</strong>armente le mod<strong>al</strong>ità di costruzione dellostrumento <strong>al</strong>l’uopo impiegato ed esponendo poi passo perpasso le operazioni da compiere per il rilevamento, contutte le regole da rispettare per l’osservazione delle direzioniangolari tra i vari siti e la loro registrazione, pur mancandoperò di <strong>in</strong>dicazioni <strong>in</strong> merito <strong>al</strong> dimensionamento edStatua di Leon Battista Alberti,sita a Firenze presso la G<strong>al</strong>leria degli UffiziLate statue of Leon Battista Alberti.Courtyard of the Uffi zi G<strong>al</strong>lery, Florence<strong>al</strong>so the recognition from the politic<strong>al</strong> and bus<strong>in</strong>ess world.The relevance of the Ptolemaic cartography (pictura) <strong>in</strong> staterelationships, trades and travels was quickly understood.Follow<strong>in</strong>g this grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest for the researches by Ptolemy,Iacopo Angeli from Scarperia, a Chrysoloras student, translatedhis master’s code <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>. Thereafter, Francesco Lappacc<strong>in</strong>iand Domenico Bon<strong>in</strong>segni created a copy of the code with<strong>al</strong>l the names of the different places translated <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>. TheGeographia by Ptolemy was therefore completely accessible toevery scholar and to whoever was <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> this fi eld ofstudy. It was the end of a millenary oblivion and the rise of atrue new “best seller” <strong>in</strong> the cartographic<strong>al</strong> gender.The years pass<strong>in</strong>g by, the Geographia became a chef d’oeuvre,http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Leon_Battista_Alberti58

Vagnetti L., Lo studio di Roma negli scritti <strong>al</strong>bertiani, <strong>in</strong> Convegno <strong>in</strong>ternazion<strong>al</strong>e <strong>in</strong>detto nel V centenario di Leon Battista Alberti, Roma-Mantova-Firenze, 25-29 aprile 1972, Roma, Accademia Nazion<strong>al</strong>e dei L<strong>in</strong>cei, Quaderno n. 209, Roma, 1974<strong>al</strong>l’orientamento dei vari poligoni rilevati.Il secondo saggio, Descriptio urbis Romae, offre <strong>al</strong>la <strong>cartografia</strong>un contributo decisamente orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>e, attraverso l’illustrazionedel metodo di restituzione grafica di una pianta urbana percoord<strong>in</strong>ate polari, raccolte ed ord<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> apposite griglie otabelle.Lo strumento ideato per la costruzione di t<strong>al</strong>i griglie dicoord<strong>in</strong>ate è ancora un goniometro, chiamato Orizon e dotatodi un raggio graduato, chiamato Radius, <strong>in</strong>cernierato nelLeon Battista Alberti,Descriptio urbis RomaeLeon Battista Alberti,Description of the town of Romere<strong>al</strong>ised on precious papers, often enriched with exquisiteworkmanships and sophisticated gold decorations. It got onthe bookshelves of the most famous and powerful importantmen of the time (such as P<strong>al</strong>la Strozzi, Lorenzo de’ Medici,Federico da Montefeltro, Alfonso d’Aragona, Borso d’Este, thePope Gregorio XII), together with those of many scholars.With this <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g popularity of the text, a new richeditori<strong>al</strong> activity beg<strong>in</strong>s. Florence becomes the heart of theproduction of diff erent k<strong>in</strong>ds of Ptolemaic Atlases and thistrend spreads to other towns <strong>in</strong> the whole Europe. That’s thestart of a fl ourish<strong>in</strong>g market of maps (even on s<strong>in</strong>gle sheets),<strong>in</strong>creased by the <strong>in</strong>terest of a lot of collectors and those keen onthe subject. The ch<strong>al</strong>cography from a pr<strong>in</strong>ted sample broadenseven more this tendency. Everyth<strong>in</strong>g started when a French59

ANNO I | n. 6 | NOVEMBRE - DICEMBRE 2009http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Florence1493.pngimmag<strong>in</strong>e riprodotta nella doppia pag<strong>in</strong>a precedente: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cellarius_ptolemaic_system.jpgVista di Firenze, 1490 circa (particolare)View of Florence <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y, around 1490 (detail)centro del medesimo goniometro, proprio come i modernirapportatori.Una volta materi<strong>al</strong>izzata su un foglio di carta la pianta diuna città rilevata con il metodo di triangolazione illustratonei ludi, il cartografo fissa su t<strong>al</strong>e rappresentazione l’orig<strong>in</strong>epr<strong>in</strong>ter, Anto<strong>in</strong>e Lafréry, active <strong>in</strong> Rome at the middle of theXVI century, re<strong>al</strong>ised the fi rst Tavole Moderne di Geografiade la Maggior parte del Mondo di diversi avtori raccolte etmesse secondo l’ord<strong>in</strong>e di Tolomeo con i disegni di moltecitta e fortezze di diverse prov<strong>in</strong>tie stampate <strong>in</strong> rame con62

di un sistema cartografico di riferimento, <strong>in</strong> un puntoposto <strong>in</strong> posizione centr<strong>al</strong>e e, a partire da questo, rileva conl’Orizon le coord<strong>in</strong>ate polari di ciascun particolare presentesul grafico, cioè direzioni e distanze d<strong>al</strong>l’orig<strong>in</strong>e, così dacostruire una tabella composta dai nomi e d<strong>al</strong>la posizionedi ciascun particolare topografico rappresentato, come unasorta di pianta criptata. T<strong>al</strong>e tabella, ricavata dunque dauna restituzione grafica e non da un rilevamento direttosul territorio, costituisce un nuovo punto di partenza peril cartografo che volesse ottenere un’<strong>al</strong>tra pianta, an<strong>al</strong>oga aquella orig<strong>in</strong>aria, con la garanzia di restituire un <strong>modello</strong>perfettamente sovrapponibile <strong>al</strong> precedente.Tempio M<strong>al</strong>atestiano,opera rimasta <strong>in</strong>compiuta di Leon Battista AlbertiM<strong>al</strong>atesta Temple,Leon Battista Alberti unf<strong>in</strong>ished workSanta Maria Novella, Firenzehttp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Leon_Battista_Albertistvdio et diligenza <strong>in</strong> Roma (Modern Geographic<strong>al</strong> Tablesof the most part of the World, by different authors andorganised accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Ptolemaic order, with draw<strong>in</strong>gsof various towns and fortresses, carefully pr<strong>in</strong>ted throughcopper plates <strong>in</strong> Rome).Besides the economic aspects, however relevant they were,the most important element was the open<strong>in</strong>g of new cultur<strong>al</strong>horizons. There was a true humus (“fertile ground”) thatcould br<strong>in</strong>g to life the It<strong>al</strong>ian “Cartographic<strong>al</strong> Renaissance”.These were the basis for the future achievements <strong>in</strong> this fi eld.Nevertheless, the renewed success of Ptolemy drove some of themost sedentary scholars to the conclusion that it was enough toread his Geographia <strong>in</strong> order to discover the whole World (or,as we would say today, to make “virtu<strong>al</strong> travels”). A persuasionclearly testifi ed by the verses written by Ludovico Ariosto(Satira III, dedicate to Sir Annib<strong>al</strong>e M<strong>al</strong>aguzzi, 1518):The libraries of the most important people were enriched bythe new and sophisticated cartographic<strong>al</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>gs of thePtolemaic Atlases. In the meanwhile, the representations ofthe territory for practic<strong>al</strong> purposes - property rights, natur<strong>al</strong>resources employment, water fl ows regulations, leg<strong>al</strong> contests,boundaries litigations between citizen or communities, accessto rights on rur<strong>al</strong> estates, forests or stretches of water – is stilll<strong>in</strong>ked to descriptive representations, sometimes with sketchesso naïf that could be today compared with child’s draw<strong>in</strong>gs.As an example, to understand how non-Ptolemaic63

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Da_V<strong>in</strong>ci_Vitruve_Luc_Viatour.jpgConsiderato solo <strong>in</strong> questi term<strong>in</strong>i, però, l’<strong>in</strong>tero metodoproposto d<strong>al</strong>la Descriptio potrebbe apparire <strong>al</strong>la f<strong>in</strong>e unamera esercitazione accademica, ancorché caratterizzatad<strong>al</strong>l’<strong>in</strong>novativo metodo del riporto per coord<strong>in</strong>ate polari,la cui v<strong>al</strong>idità risulterebbe, <strong>al</strong> primo acchito, confermataesclusivamente ai f<strong>in</strong>i della riproduzione fedele di una pianta;la novità <strong>in</strong>trodotta da t<strong>al</strong>e metodo non è affatto limitata<strong>al</strong>la sola replica <strong>geometrica</strong> dell’orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>e mappa rilevata,<strong>al</strong>la qu<strong>al</strong>e pur si potrebbe giungere semplicemente perlucidatura del primo <strong>modello</strong>, ma consiste nell’<strong>in</strong>troduzionedel concetto di “sc<strong>al</strong>abilità” del dato orig<strong>in</strong>ario, consentendo<strong>al</strong> cartografo di ricavare, dai medesimi dati di posizione, nschemi di impianto planimetrico simili, tutti <strong>in</strong> rapportodiverso d<strong>al</strong> primo <strong>modello</strong>, e qu<strong>in</strong>di anche d<strong>al</strong> vero, <strong>al</strong> variaredel fattore di proporzion<strong>al</strong>ità scelto per la def<strong>in</strong>izione delledistanze d<strong>al</strong>l’orig<strong>in</strong>e, cioè della sc<strong>al</strong>a di rappresentazione dellamappa.Anche se Alberti non re<strong>al</strong>izza una pianta urbana così comeoggi noi la <strong>in</strong>tendiamo, il suo metodo segna di fatto unmomento importantissimo nella storia della Cartografia,che va <strong>al</strong> di là del primato, pur non secondario, relativo<strong>al</strong>la rappresentazione urbana della “Città eterna”, perché,proprio con l’ideazione di questo metodo di posizionamentoper coord<strong>in</strong>ate polari, si propone un criterio oggettivo direstituzione grafica della pianta di una città e qu<strong>in</strong>di ripetibileanche <strong>al</strong> variare dell’artefice.Da questa esperienza si apre def<strong>in</strong>itivamente la strada dellar<strong>in</strong>ascenza cartografica, con l’affrancamento da quell’approcciofantastico o anagogico, tipico di certa <strong>cartografia</strong> mediev<strong>al</strong>e,e si segnano i prodromi di quella rivoluzione che due secolidopo avrebbe posto il problema del posizionamento <strong>al</strong> centrodella problematica cartografica.Sullo specifico piano della rappresentazione, è <strong>al</strong> contributodei nuovi topografi, pittori e m<strong>in</strong>iaturisti r<strong>in</strong>asciment<strong>al</strong>i chesi deve il raggiungimento di un ulteriore progresso per lare<strong>al</strong>izzazione di mappe dotate di sempre maggiori capacitàespressive e descrittive.A distanza di circa c<strong>in</strong>quant’anni d<strong>al</strong>la redazione dei saggi<strong>al</strong>bertiani, un’<strong>al</strong>tra figura imponente della storia della scienzae dell’arte, Leonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci (1452 - 1519), apporta <strong>al</strong>ladiscipl<strong>in</strong>a un contributo di orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>ità senza precedenti, <strong>sulla</strong>scorta delle conoscenze della Geographia di Tolomeo e deisaggi di Leon Battista Alberti, sia nelle operazioni di disegnod<strong>al</strong> vero con strumenti prospettografici (come il “Velo”<strong>in</strong>ventato d<strong>al</strong>lo stesso Alberti per rendere controllabili d<strong>al</strong>punto di vista geometrico le vedute prospettiche), sia nelleoperazioni di rilevamento, sia nella redazione delle carte.La produzione cartografica di Leonardo si staglia millemiglia verso l’<strong>al</strong>to rispetto agli <strong>in</strong>genui ed <strong>in</strong>fantili disegni diLeonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci, Uomo VitruvianoLeonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci, Vitruvian Manrepresentations of the land were simplistic, we should look attwo maps of Tuscany from the XV century: the “Copia di unantico disegno rappresentante i laghi di Sesto, di Bient<strong>in</strong>a edi V<strong>al</strong>d<strong>in</strong>ievole dell’anno 1450 circa” [“Copy of an ancientmap of the lakes of Sesto, of Bient<strong>in</strong>a and of V<strong>al</strong>d<strong>in</strong>ievole-1450 approx.-”] and the “Carta trovata nell’archivio deiMonaci Cass<strong>in</strong>esi di S.Flora e Lucilla di Arezzo” [“Mapfound <strong>in</strong> the Archives of the Cass<strong>in</strong>o monks of S. Flora andLucilla near Arezzo”], <strong>in</strong> the same years.The fi rst one, without consider<strong>in</strong>g any exact metric<strong>al</strong>measurement, gives the location of build-up areas, roads,rivers, mounta<strong>in</strong>s (with their specifi c topographic<strong>al</strong> names).The second one, similarly lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> any geometric<strong>al</strong> l<strong>in</strong>kwith the re<strong>al</strong>ity, describes settl<strong>in</strong>gs, roads and bridges, rivers,navigable stretches of water, and land uses, with <strong>al</strong>l the namesof the places and the different roads.Most of <strong>al</strong>l, Ptolemy teaches that a portion of a spheric<strong>al</strong>surface can be represented on a plane through projections andright geographic<strong>al</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ates. The land surveyors of the timedidn’t become immediately aware of this lesson. Therefore,there was a relevant diff erence between geographic<strong>al</strong> andchorographic<strong>al</strong> representations follow<strong>in</strong>g the Ptolemaic theoryand topographic<strong>al</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>gs where imitation still resistedaga<strong>in</strong>st geometric<strong>al</strong> rules.In his translation from Greek <strong>in</strong>to Lat<strong>in</strong> of the Ptolemy’sGeographia, Iacopo Angeli from Scarperia put a strongevidence on the revolutionary <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>in</strong>troduced by thework of the scientist from Alexandria: a demonstration of howto trace a sphere on a plane surface, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the “proportiocuiusque partis ad univers<strong>al</strong>e” [the proportions between thes<strong>in</strong>gle parts and the whole]. Nevertheless, only after many years,with<strong>in</strong> the cultur<strong>al</strong> context of the Renaissance, a new <strong>in</strong>teresttowards cartography grew <strong>al</strong>so among the technicians. Thatgave way to new studies, and orig<strong>in</strong>ated many cartographic<strong>al</strong>treatises.The leader of this generation of scientists was Leon BattistaAlberti. He recovered the middle-age know-how and thecontribution of the Ptolemaic Geographia <strong>in</strong> order to<strong>in</strong>troduce new theories and new methods <strong>in</strong> the cartographic<strong>al</strong>and topographic<strong>al</strong> fi elds.Two m<strong>in</strong>or works of Alberti represent the fi rst step <strong>in</strong>the cartographic<strong>al</strong> modell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> It<strong>al</strong>y: Ex ludis rerummathematicarum, ended before 1450, and Descriptio urbisRomae, written between 1443 and 1455. Other <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gclues can be found <strong>in</strong> De Pictura, <strong>in</strong> De Statua, and De reaedificatoria.The fi rst of these essays conta<strong>in</strong>s, among other th<strong>in</strong>gs, a sort ofante litteram “handbook” of Topography. Parti<strong>al</strong>ly recover<strong>in</strong>ga long scholar tradition dat<strong>in</strong>g up to Euclid, <strong>in</strong> this text Alberticollects the most important mathematic tricks that can giveanswers to measurement problems that are apparently withouta solution, unless a method of <strong>in</strong>direct c<strong>al</strong>culation is applied.The problems presented by an <strong>in</strong>direct measurement of distances65

ANNO I | n. 6 | NOVEMBRE - DICEMBRE 2009territorio dei tanti agrimensori e periti del suo tempo, anchese il suo avvic<strong>in</strong>amento <strong>al</strong>la rappresentazione cartograficanon deriva certo da <strong>in</strong>tenti di tipo profession<strong>al</strong>e.Leonardo non è un cartografo <strong>in</strong> senso stretto, ma si occupadi <strong>cartografia</strong> per specifiche necessità di studio e per esigenzedi an<strong>al</strong>isi, f<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>izzate <strong>al</strong>la progettazione territori<strong>al</strong>e o <strong>al</strong>lapianificazione di attività belliche.Per entrare più direttamente nel merito delle sue operecartografiche bisogna prelim<strong>in</strong>armente spostare l’attenzioned<strong>al</strong> mondo delle mappe a quello della rappresentazione <strong>in</strong>gener<strong>al</strong>e, cioè del disegno e della pittura, che per Leonardo nonsono semplicemente un l<strong>in</strong>guaggio per ripetere visivamentecose già note, ma, come ha osservato Giulio Carlo Argan,“sono la chiave con cui si penetra nel mondo dei fenomeni”.È <strong>in</strong>fatti dai precetti derivanti d<strong>al</strong> Libro di pittura che sirecuperano i fondamenti <strong>in</strong>novativi della sua produzionecartografica.La formula adotta da Leonardo nel rilevamento e nellarappresentazione cartografica è s<strong>in</strong>tetizzata nel precetto cheegli stesso ferma nei suoi appunti del Manoscritto L dell’Istitutodi Francia, dove egli annota: “scorta sulle sommità e <strong>in</strong> su’ latidei colli le figure di terreni e le sue divisioni e nelle cose voltea te, f<strong>al</strong>e <strong>in</strong> propria forma” (Ms. L dell’Istituto di Francia, f. 21are solved through the use of the fi rst pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of similitudebetween right-angled triangles and through the so c<strong>al</strong>led “ruleof three”. However, the most relevant contribution of this workconsist <strong>in</strong> a new method of topographic<strong>al</strong> survey<strong>in</strong>g that ismeant to solve the question of the mutu<strong>al</strong> position on the urbansc<strong>al</strong>e through a triangulation work. Such a work had <strong>al</strong>readybeen anticipated by Giovanni Fontana <strong>in</strong> his Tractatus detrigono b<strong>al</strong>istario abbreviatus […] <strong>in</strong> 1440. This essay wasrecovered and completed by diff erent Renaissance scholars, andwas furthermore ameliorated for other fi ve centuries, untilnowadays.For this triangulation, they used a goniometer divided <strong>in</strong> 48parts, still without an <strong>al</strong>idade and a compass po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g to themagnetic North, and still with the help of a plumb l<strong>in</strong>e.Alberti fully describes his method, expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g how tomanufacture the adequate <strong>in</strong>strument and, step by step,how operate <strong>in</strong> order to obta<strong>in</strong> a correct survey. Moreover, heexpla<strong>in</strong>s <strong>al</strong>l the rules to follow <strong>in</strong> the observation of the angulardirections among the diff erent sites and <strong>in</strong> their registrations.Nevertheless, there are no <strong>in</strong>structions about the representationof the dimensions and the orientation of the various polygonssurveyed.The second essay, Descriptio urbis Romae, is a much moreorig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> step forward. It shows how an urban plan could besketched on a map, accord<strong>in</strong>g to polar coord<strong>in</strong>ates collectedand organised with<strong>in</strong> standard tables.The <strong>in</strong>strument that enables the technicians to draw suchtables is a protractor, c<strong>al</strong>led Orizon. It is provided with agraduated radius that is h<strong>in</strong>ged <strong>in</strong> the middle of the <strong>in</strong>strumentitself, exactly as it happens <strong>in</strong> the modern, graduated circularprotractor hav<strong>in</strong>g a pivoted arm, used for measur<strong>in</strong>g ormark<strong>in</strong>g off angles.When it has represented on a sheet of paper the plan of a townmeasured through the triangulation method expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> theLudi, a surveyor establish <strong>in</strong> this representation the basis of acartographic system of reference: start<strong>in</strong>g from a centr<strong>al</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t,he can measure with the Orizon the polar coord<strong>in</strong>ates of everys<strong>in</strong>gle place on the graphic. We are t<strong>al</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about distances andangles from a start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t that can give way to the sett<strong>in</strong>gdown of a table with the name and the position of everyrepresented topographic<strong>al</strong> detail, a sort of encrypted map. Sucha table, obta<strong>in</strong>ed through a graphic<strong>al</strong> representation and notby a practic<strong>al</strong> survey on the fi eld, represents a revolutionarystep forward: the cartographer will<strong>in</strong>g to obta<strong>in</strong> another map,identic<strong>al</strong> to the orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> one, could certa<strong>in</strong>ly be able to make acopy perfectly match<strong>in</strong>g the fi rst sample.Considered from this po<strong>in</strong>t of view, the whole method suggestedby the Descriptio could appear like a mere academic exercise:the advantages of tak<strong>in</strong>g polar coord<strong>in</strong>ates as a reference areobvious at fi rst sight, as such a process <strong>al</strong>lows the creation ofa faithful reproduction from an orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> map. However, thismethod is by far more productive than a simple techniquefor a geometric<strong>al</strong> copy of a topographic<strong>al</strong> map (a copy thathttp://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_self.jpg66

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mona_Lisa-restored.jpgLeonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,Monna Lisa dopo il restauro (particolare)Leonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,Mona Lisa restored (detail)could be re<strong>al</strong>ised by an easy trac<strong>in</strong>g from fi rst model). Itsre<strong>al</strong> <strong>in</strong>novation consists <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>troduction of the concept of“sc<strong>al</strong>ability” start<strong>in</strong>g from the re<strong>al</strong> measurements. In such away, the cartographer can draw from the same position<strong>al</strong> dataa n number of maps, identic<strong>al</strong> as for their proportions, but <strong>al</strong>ldiff erent <strong>in</strong> their sc<strong>al</strong>e if compared with the model, accord<strong>in</strong>gto the decrease factor chosen <strong>in</strong> the defi nition of the distancesfrom the orig<strong>in</strong> (sc<strong>al</strong>e of the map).67

ANNO I | n. 6 | NOVEMBRE - DICEMBRE 2009Leonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,Carta dell’It<strong>al</strong>ia Centro-NordLeonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,Map of the Northern and Centr<strong>al</strong> Parts of It<strong>al</strong>yEven if Alberti didn’t draw a map of a town as we knowit today, his method represents a milestone <strong>in</strong> the History ofCartography. It goes far beyond the creation of the fi rst mapof the “Etern<strong>al</strong> City” (Rome): by referr<strong>in</strong>g every position topolar coord<strong>in</strong>ates it is possible to fi x a objective criterion fora graphic<strong>al</strong> reproduction of an urban plan, and, therefore, toreplicate it authentic<strong>al</strong>ly <strong>al</strong>so chang<strong>in</strong>g the mapmaker.This experience gives way once and for <strong>al</strong>l to the Cartographic<strong>al</strong>Renaissance, abandon<strong>in</strong>g the fantastic<strong>al</strong> and an<strong>al</strong>ogic<strong>al</strong>approach that was typic<strong>al</strong> of the Middle Age. It is the fi rststep towards the revolution that, with<strong>in</strong> two centuries, wouldput the problem of the position at the core of the wholeW<strong>in</strong>dsor Castle, Roy<strong>al</strong> Library, 1227768

). Il passaggio d<strong>al</strong> rilievo <strong>al</strong>la carta avviene poi attraverso unas<strong>in</strong>tesi <strong>in</strong>dividu<strong>al</strong>e di elementi percettivi, metrici ed ord<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>i,che propongono sempre una visione diagrammatica dellospazio, percepito e del<strong>in</strong>eato nella sua unitarietà.Il suo più <strong>al</strong>to contributo <strong>al</strong>la rappresentazione del territorioriguarda speci<strong>al</strong>mente la componente vertic<strong>al</strong>e dei monti edei laghi. Il metodo che Leonardo impiega nella restituzionegrafica delle masse orografiche si basa sul tentativo didel<strong>in</strong>eazione delle forme di monti e coll<strong>in</strong>e nel rispetto deiloro mutui rapporti di proporzion<strong>al</strong>ità e nell’<strong>in</strong>troduzionedella sua teoria delle ombre, che conferisce <strong>al</strong>le carte unaforza comunicativa senza precedenti e conferma l’importanzacartographic<strong>al</strong> science.T<strong>al</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about the representation, dur<strong>in</strong>g the Renaissancenew surveyors, pa<strong>in</strong>ters and m<strong>in</strong>iaturists went further <strong>in</strong>tothe creation of maps with greater power of description andexpression.After more or less fi fty years s<strong>in</strong>ce the publish<strong>in</strong>g of Alberti’sessays, another genius <strong>in</strong> both Art and Science, Leonardo daV<strong>in</strong>ci (1452-1519), gave a unique, orig<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong> contributionto this discipl<strong>in</strong>e, thanks to the methods proposed by LeonBattista Alberti and to the Ptolemaic Geographia, both <strong>in</strong>the draw<strong>in</strong>g techniques from the re<strong>al</strong>ity (through perspective<strong>in</strong>struments such as the “Velo”, conceived by Alberti <strong>in</strong> orderto establish a geometric<strong>al</strong> correspondence with a perspectiveview) and <strong>in</strong> the methods of survey<strong>in</strong>g and sketch<strong>in</strong>g maps.Leonardo’s maps stand out a mile from the naïve and childishsketches re<strong>al</strong>ised by the surveyors and the experts of the time,even if his <strong>in</strong>terest for the cartographic<strong>al</strong> representation doesn’thave a profession<strong>al</strong> purpose.Leonardo isn’t a cartographer, but he de<strong>al</strong>s with this sciencefor scientifi c and an<strong>al</strong>ytic purposes: landscape plann<strong>in</strong>g andwar strategies.In order to understand his cartographic<strong>al</strong> work, we need totake a step beh<strong>in</strong>d, shift<strong>in</strong>g our focus from the maps to therepresentations more <strong>in</strong> gener<strong>al</strong>; that’s to say to the language ofthe draw<strong>in</strong>gs and of the pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gs. For Leonardo, this latterwasn’t a mere visu<strong>al</strong> repetition of what was <strong>al</strong>ready known;<strong>in</strong>stead, it was “the key to open the world of phenomena” (asGiulio Carlo Argan said).The <strong>in</strong>novative basis of his cartographic<strong>al</strong> production, therefore,can be found <strong>in</strong> the rules enunciated <strong>in</strong> the Libro di pittura.The way Leonardo chooses to survey and graphic<strong>al</strong>ly representa piece of land is summarised <strong>in</strong> the rule given <strong>in</strong> his own note<strong>in</strong> the Manuscript L, France Institute (f. 21 r): “On the topof the hills and on theirs sides, look at the shapes of the landportions, at their division, and at <strong>al</strong>l the th<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> front ofyou, and draw them <strong>in</strong> their own shape”. The transformationfrom the sketch to the map is done through a person<strong>al</strong> synthesisof perceptive elements, metric and ord<strong>in</strong><strong>al</strong>, <strong>al</strong>ways giv<strong>in</strong>g adiagrammatic<strong>al</strong> view of the land (conceived and representedas a whole).Leonardo’s contribution to an accurate landscape representationis particularly relevant for what concerns the vertic<strong>al</strong> componentof mounta<strong>in</strong>s and hydrography. In the graphic<strong>al</strong> reproductionof mounta<strong>in</strong>ous blocks, he tries to sketch the shapes of everymassif and hill follow<strong>in</strong>g their mutu<strong>al</strong> proportions. Moreover,his “theory of the shadows” gives to the maps a communicativepower never achieved before, a proof of the importance of acareful study on them. “… shades <strong>in</strong> pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g need much more<strong>in</strong>vestigation and speculation than their outl<strong>in</strong>e; and evidenceof this precept is that the outl<strong>in</strong>e can be made to sh<strong>in</strong>e us<strong>in</strong>gveils transparency, or fl at glass placed between the eye and theth<strong>in</strong>g to be drawn; but this rule does not apply to shades, dueto the lack of sensitivity of their shape, for, more often than69

ANNO I | n. 6 | NOVEMBRE - DICEMBRE 2009Leonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,Carta della V<strong>al</strong>dichianaLeonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,Map of V<strong>al</strong>dichianache per Leonardo ha il loro profondo studio: “Di moltomaggiore <strong>in</strong>vestigazione e speculazione sono le ombre nellapittura che i loro l<strong>in</strong>eamenti; e la prova di questo s’<strong>in</strong>segnache i l<strong>in</strong>eamenti si possono lucidare con veli, o vetri piani<strong>in</strong>terposti fra l’occhio e la cosa che si deve lucidare; ma leombre non sono comprese da t<strong>al</strong>e regola, per l’<strong>in</strong>sensibilitàdei loro term<strong>in</strong>i, i qu<strong>al</strong>i il più delle volte sono confusi”(Leonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci, Libro di Pittura).Così, è da riscontrare il geni<strong>al</strong>e uso di luce ed ombra, adottatoper la Carta dell’It<strong>al</strong>ia centro-nord, nella qu<strong>al</strong>e Leonardo<strong>in</strong>troduce una mod<strong>al</strong>ità di rappresentazione che consenteuna percezione delle variazioni di quota del territoriocartografato, senza precedenti nella storia della Cartografia,e che può essere riconosciuta come l’archetipo della tecnicadi rappresentazione orografica a t<strong>in</strong>te ipsometriche, ancoraoggi adottata per la re<strong>al</strong>izzazione degli atlanti scolastici delnostro tempo e riproducente con efficacia ed immediatezza ilconcetto di “più scuro più <strong>al</strong>to”.not, they are undefi ned or uncerta<strong>in</strong>...” (Leonardo da V<strong>in</strong>ci,c. 1508-10).Therefore, we have to take <strong>in</strong>to account the clever use of lightsand shadows <strong>in</strong> the Carta dell’It<strong>al</strong>ia centro-nord (W<strong>in</strong>dsor,RL 12277). In this map, Leonardo <strong>in</strong>troduces a new way ofrepresentation that makes it possible to perceive the diff erencesof <strong>al</strong>titude <strong>in</strong> the landscape. Such a method had never beenpreviously applied <strong>in</strong> cartography and constitutes the archetypeof the way to represent an <strong>al</strong>titude through hypsometric colours(a method nowadays still <strong>in</strong> use for school atlases and apractic<strong>al</strong> and understandable example of the abstract concept“the darker, the higher”).Together with the representation of a mounta<strong>in</strong> shape, evenLeonardo’s hydrographic<strong>al</strong> sketches are a demonstration of thesame idea of three-dimension<strong>al</strong>ity, obta<strong>in</strong>ed with the samemethod, <strong>al</strong>though with the opposite concept “the darker, thedeepest”. The best example is the Carta della V<strong>al</strong>dichiana(W<strong>in</strong>dsor, RL 12278r), where the sh<strong>al</strong>low stretch of water<strong>in</strong> the v<strong>al</strong>ley contrasts with the deepest waters of its tributaryfl ows, thanks to the use of diff erent tones of blue for every levelof depth.W<strong>in</strong>dsor Castle, Roy<strong>al</strong> Library, 12278r70

An<strong>al</strong>ogamente <strong>al</strong>l’orografia, anche nell’idrografia Leonardoesprime l’idea di tridimension<strong>al</strong>ità attraverso la stessa tecnica,richiamando il concetto <strong>in</strong>verso: “più scuro, più profondo”,come nella Carta della V<strong>al</strong>dichiana, dove contrapponeil poco profondo specchio d’acqua della Chiana, ai piùfondi flussi idrici dei torrenti tributari dello stesso bac<strong>in</strong>o,segn<strong>al</strong>andone con diverse ton<strong>al</strong>ità di azzurro le differentidepressioni.La seconda parte del testo, “Da Raffaello Sanzio aGiambattista Nolli” sarà pubblicata nel prossimonumero di GEOCENTRO/magaz<strong>in</strong>eThe second part of the text “From Raffaello Sanzioto Giambattista Nolli” will be published <strong>in</strong> the nextnumber.CAODURO ® s.p.aCAVAZZALE - VICENZA<strong>in</strong>fo@caoduro.it - www.caoduro.it