Ergativität in der modernen generativen Grammatik

Ergativität in der modernen generativen Grammatik

Ergativität in der modernen generativen Grammatik

Erfolgreiche ePaper selbst erstellen

Machen Sie aus Ihren PDF Publikationen ein blätterbares Flipbook mit unserer einzigartigen Google optimierten e-Paper Software.

Über die Spur t, die die bewegte Konstituente an ihrer ursprünglichen Position h<strong>in</strong>terläßt, kann auch<br />

<strong>der</strong> Oberflächenstruktur die Information entnommen werden, daß diese Konstituente auf <strong>der</strong> TS<br />

Objektstatus hatte und also <strong>in</strong>ternes Argument ist. Für die NPgilt hier also die folgende Reihe:<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternes Argument – Patiens – TS: unmittelbar von VP dom<strong>in</strong>ierte NP – TS-Objekt – OS:<br />

unmittelbar von S dom<strong>in</strong>ierte NP – OS-Subjekt – Subjektskasus<br />

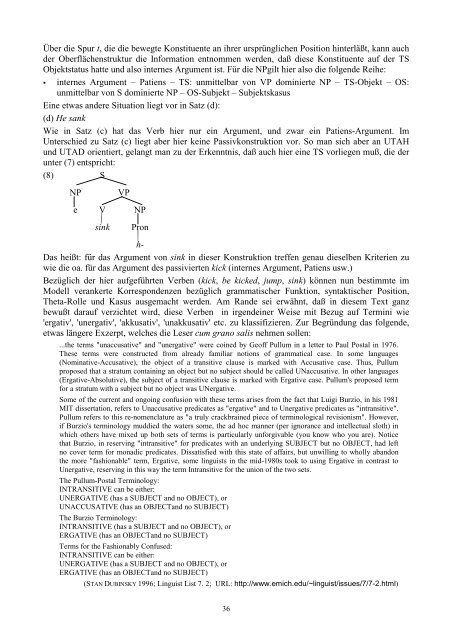

E<strong>in</strong>e etwas an<strong>der</strong>e Situation liegt vor <strong>in</strong> Satz (d):<br />

(d) He sank<br />

Wie <strong>in</strong> Satz (c) hat das Verb hier nur e<strong>in</strong> Argument, und zwar e<strong>in</strong> Patiens-Argument. Im<br />

Unterschied zu Satz (c) liegt aber hier ke<strong>in</strong>e Passivkonstruktion vor. So man sich aber an UTAH<br />

und UTAD orientiert, gelangt man zu <strong>der</strong> Erkenntnis, daß auch hier e<strong>in</strong>e TS vorliegen muß, die <strong>der</strong><br />

unter (7) entspricht:<br />

(8) S<br />

NP VP<br />

e V NP<br />

s<strong>in</strong>k Pron<br />

h-<br />

Das heißt: für das Argument von s<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong> dieser Konstruktion treffen genau dieselben Kriterien zu<br />

wie die oa. für das Argument des passivierten kick (<strong>in</strong>ternes Argument, Patiens usw.)<br />

Bezüglich <strong>der</strong> hier aufgeführten Verben (kick, be kicked, jump, s<strong>in</strong>k) können nun bestimmte im<br />

Modell verankerte Korrespondenzen bezüglich grammatischer Funktion, syntaktischer Position,<br />

Theta-Rolle und Kasus ausgemacht werden. Am Rande sei erwähnt, daß <strong>in</strong> diesem Text ganz<br />

bewußt darauf verzichtet wird, diese Verben <strong>in</strong> irgende<strong>in</strong>er Weise mit Bezug auf Term<strong>in</strong>i wie<br />

'ergativ', 'unergativ', 'akkusativ', 'unakkusativ' etc. zu klassifizieren. Zur Begründung das folgende,<br />

etwas längere Exzerpt, welches die Leser cum grano salis nehmen sollen:<br />

...the terms "unaccusative" and "unergative" were co<strong>in</strong>ed by Geoff Pullum <strong>in</strong> a letter to Paul Postal <strong>in</strong> 1976.<br />

These terms were constructed from already familiar notions of grammatical case. In some languages<br />

(Nom<strong>in</strong>ative-Accusative), the object of a transitive clause is marked with Accusative case. Thus, Pullum<br />

proposed that a stratum conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an object but no subject should be called UNaccusative. In other languages<br />

(Ergative-Absolutive), the subject of a transitive clause is marked with Ergative case. Pullum's proposed term<br />

for a stratum with a subject but no object was UNergative.<br />

Some of the current and ongo<strong>in</strong>g confusion with these terms arises from the fact that Luigi Burzio, <strong>in</strong> his 1981<br />

MIT dissertation, refers to Unaccusative predicates as "ergative" and to Unergative predicates as "<strong>in</strong>transitive".<br />

Pullum refers to this re-nomenclature as "a truly crackbra<strong>in</strong>ed piece of term<strong>in</strong>ological revisionism". However,<br />

if Burzio's term<strong>in</strong>ology muddied the waters some, the ad hoc manner (per ignorance and <strong>in</strong>tellectual sloth) <strong>in</strong><br />

which others have mixed up both sets of terms is particularly unforgivable (you know who you are). Notice<br />

that Burzio, <strong>in</strong> reserv<strong>in</strong>g "<strong>in</strong>transitive" for predicates with an un<strong>der</strong>ly<strong>in</strong>g SUBJECT but no OBJECT, had left<br />

no cover term for monadic predicates. Dissatisfied with this state of affairs, but unwill<strong>in</strong>g to wholly abandon<br />

the more "fashionable" term, Ergative, some l<strong>in</strong>guists <strong>in</strong> the mid-1980s took to us<strong>in</strong>g Ergative <strong>in</strong> contrast to<br />

Unergative, reserv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this way the term Intransitive for the union of the two sets.<br />

The Pullum-Postal Term<strong>in</strong>ology:<br />

INTRANSITIVE can be either:<br />

UNERGATIVE (has a SUBJECT and no OBJECT), or<br />

UNACCUSATIVE (has an OBJECTand no SUBJECT)<br />

The Burzio Term<strong>in</strong>ology:<br />

INTRANSITIVE (has a SUBJECT and no OBJECT), or<br />

ERGATIVE (has an OBJECTand no SUBJECT)<br />

Terms for the Fashionably Confused:<br />

INTRANSITIVE can be either:<br />

UNERGATIVE (has a SUBJECT and no OBJECT), or<br />

ERGATIVE (has an OBJECTand no SUBJECT)<br />

(STAN DUBINSKY 1996; L<strong>in</strong>guist List 7. 2; URL: http://www.emich.edu/~l<strong>in</strong>guist/issues/7/7-2.html)<br />

36