The lives of the poets from The Dictionary of National Biography ...

The lives of the poets from The Dictionary of National Biography ...

The lives of the poets from The Dictionary of National Biography ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

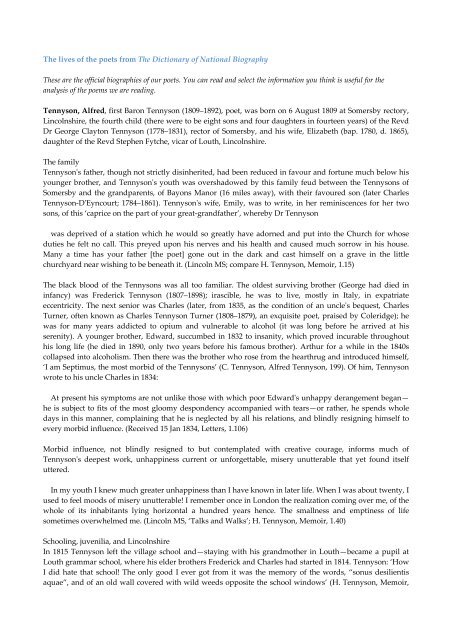

<strong>The</strong> <strong>lives</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>poets</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Dictionary</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>National</strong> <strong>Biography</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong>se are <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial biographies <strong>of</strong> our <strong>poets</strong>. You can read and select <strong>the</strong> information you think is useful for <strong>the</strong><br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poems we are reading.<br />

Tennyson, Alfred, first Baron Tennyson (1809–1892), poet, was born on 6 August 1809 at Somersby rectory,<br />

Lincolnshire, <strong>the</strong> fourth child (<strong>the</strong>re were to be eight sons and four daughters in fourteen years) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revd<br />

Dr George Clayton Tennyson (1778–1831), rector <strong>of</strong> Somersby, and his wife, Elizabeth (bap. 1780, d. 1865),<br />

daughter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Revd Stephen Fytche, vicar <strong>of</strong> Louth, Lincolnshire.<br />

<strong>The</strong> family<br />

Tennysonʹs fa<strong>the</strong>r, though not strictly disinherited, had been reduced in favour and fortune much below his<br />

younger bro<strong>the</strong>r, and Tennysonʹs youth was overshadowed by this family feud between <strong>the</strong> Tennysons <strong>of</strong><br />

Somersby and <strong>the</strong> grandparents, <strong>of</strong> Bayons Manor (16 miles away), with <strong>the</strong>ir favoured son (later Charles<br />

Tennyson‐DʹEyncourt; 1784–1861). Tennysonʹs wife, Emily, was to write, in her reminiscences for her two<br />

sons, <strong>of</strong> this ‘caprice on <strong>the</strong> part <strong>of</strong> your great‐grandfa<strong>the</strong>r’, whereby Dr Tennyson<br />

was deprived <strong>of</strong> a station which he would so greatly have adorned and put into <strong>the</strong> Church for whose<br />

duties he felt no call. This preyed upon his nerves and his health and caused much sorrow in his house.<br />

Many a time has your fa<strong>the</strong>r [<strong>the</strong> poet] gone out in <strong>the</strong> dark and cast himself on a grave in <strong>the</strong> little<br />

churchyard near wishing to be beneath it. (Lincoln MS; compare H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.15)<br />

<strong>The</strong> black blood <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tennysons was all too familiar. <strong>The</strong> oldest surviving bro<strong>the</strong>r (George had died in<br />

infancy) was Frederick Tennyson (1807–1898); irascible, he was to live, mostly in Italy, in expatriate<br />

eccentricity. <strong>The</strong> next senior was Charles (later, <strong>from</strong> 1835, as <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> an uncleʹs bequest, Charles<br />

Turner, <strong>of</strong>ten known as Charles Tennyson Turner (1808–1879), an exquisite poet, praised by Coleridge); he<br />

was for many years addicted to opium and vulnerable to alcohol (it was long before he arrived at his<br />

serenity). A younger bro<strong>the</strong>r, Edward, succumbed in 1832 to insanity, which proved incurable throughout<br />

his long life (he died in 1890, only two years before his famous bro<strong>the</strong>r). Arthur for a while in <strong>the</strong> 1840s<br />

collapsed into alcoholism. <strong>The</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re was <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>r who rose <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> hearthrug and introduced himself,<br />

‘I am Septimus, <strong>the</strong> most morbid <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tennysons’ (C. Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson, 199). Of him, Tennyson<br />

wrote to his uncle Charles in 1834:<br />

At present his symptoms are not unlike those with which poor Edwardʹs unhappy derangement began—<br />

he is subject to fits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most gloomy despondency accompanied with tears—or ra<strong>the</strong>r, he spends whole<br />

days in this manner, complaining that he is neglected by all his relations, and blindly resigning himself to<br />

every morbid influence. (Received 15 Jan 1834, Letters, 1.106)<br />

Morbid influence, not blindly resigned to but contemplated with creative courage, informs much <strong>of</strong><br />

Tennysonʹs deepest work, unhappiness current or unforgettable, misery unutterable that yet found itself<br />

uttered.<br />

In my youth I knew much greater unhappiness than I have known in later life. When I was about twenty, I<br />

used to feel moods <strong>of</strong> misery unutterable! I remember once in London <strong>the</strong> realization coming over me, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

whole <strong>of</strong> its inhabitants lying horizontal a hundred years hence. <strong>The</strong> smallness and emptiness <strong>of</strong> life<br />

sometimes overwhelmed me. (Lincoln MS, ‘Talks and Walks’; H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.40)<br />

Schooling, juvenilia, and Lincolnshire<br />

In 1815 Tennyson left <strong>the</strong> village school and—staying with his grandmo<strong>the</strong>r in Louth—became a pupil at<br />

Louth grammar school, where his elder bro<strong>the</strong>rs Frederick and Charles had started in 1814. Tennyson: ‘How<br />

I did hate that school! <strong>The</strong> only good I ever got <strong>from</strong> it was <strong>the</strong> memory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> words, “sonus desilientis<br />

aquae”, and <strong>of</strong> an old wall covered with wild weeds opposite <strong>the</strong> school windows’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir,

1.7). In 1820 he left Louth, to be educated at home by his learned, violent, and <strong>of</strong>ten drunken fa<strong>the</strong>r—who<br />

believed in him. ‘My fa<strong>the</strong>r who was a sort <strong>of</strong> Poet himself thought so highly <strong>of</strong> my first essay that he<br />

prophesied I should be <strong>the</strong> greatest Poet <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Time’ (Trinity Notebook, 34).<br />

Tennyson was to recall ruefully his youthful ambitions and poetical models. It was <strong>the</strong> mouthability <strong>of</strong><br />

poetry, <strong>the</strong> urge to roll it aloud, that drew him.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first poetry that moved me was my own at five years old. When I was eight, I remember making a line<br />

I thought grander than Campbell, or Byron, or Scott. I rolled it out, it was this: ‘With slaughterous sons <strong>of</strong><br />

thunder rolled <strong>the</strong> flood’—great nonsense <strong>of</strong> course, but I thought it fine. (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.93)<br />

He was much moved by <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> Byron in 1824: ‘I was fourteen when I heard <strong>of</strong> his death. It seemed an<br />

awful calamity; I remember I rushed out <strong>of</strong> doors, sat down by myself, shouted aloud, and wrote on <strong>the</strong><br />

sandstone: “Byron is dead!”’ (ibid., 69).<br />

Before I could read, I was in <strong>the</strong> habit on a stormy day <strong>of</strong> spreading my arms to <strong>the</strong> wind, and crying out ‘I<br />

hear a voice thatʹs speaking in <strong>the</strong> wind’, and <strong>the</strong> words ‘far, far away’ had always a strange charm for me.<br />

Tennyson spoke <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> three‐book epic (‘à la Scott’) written in his ‘very earliest teens’. ‘I never felt so<br />

inspired—I used to compose 60 or 70 lines in a breath. I used to shout <strong>the</strong>m about <strong>the</strong> silent fields, leaping<br />

over <strong>the</strong> hedges in my excitement’ (Trinity Notebook, 34; H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.11–12) .<br />

Tennysonʹs prodigious excitement is evidenced in <strong>the</strong> play he wrote (1823–4) in imitation <strong>of</strong> Elizabethan<br />

comedy, <strong>The</strong> Devil and <strong>the</strong> Lady, a wondrous pastiche, alive in its ambivalent erotic deploring, its vistas <strong>of</strong><br />

space, its anatomizing <strong>of</strong> old age, and its grim humour. Duller, placatingly conventional, <strong>the</strong>re was<br />

published in April 1827, by J. and J. Jackson, booksellers <strong>of</strong> Louth, Poems by Two Bro<strong>the</strong>rs (three bro<strong>the</strong>rs,<br />

since Frederick supplied four poems for this volume by Charles and Alfred); it earned <strong>the</strong>m £20 (more than<br />

half in books) and courteous flat notices in <strong>the</strong> Literary Chronicle (19 May 1827) and <strong>the</strong> Gentlemanʹs<br />

Magazine (June). Tennysonʹs unoriginal contributions were written ‘between 15 and 17’ (1893 reissue <strong>of</strong><br />

1827, quoting Tennyson). Wisely, he did not include any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m in later editions <strong>of</strong> his works.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> Lincolnshire <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs young days was alive in his late poems, notably those in dialect,<br />

‘wonderful studies in English vernacular life’ as Richard Holt Hutton called <strong>the</strong>m (Hutton, 380). Tennysonʹs<br />

gruff gnarled humour here found its local habitation and intonation, audible in his own recorded reading <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> best <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m, ‘Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Farmer: New Style’, ‘founded’, as Tennyson said, on a single sentence: ‘When I<br />

canters my ʹerse along <strong>the</strong> ramper [highway] I ʹears “proputty, proputty, proputty”’ (Poems, 2.688).<br />

Cambridge, Arthur Hallam, and early accomplishments<br />

In November 1827 Tennyson entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where Charles had just joined Frederick.<br />

He was unhappy <strong>the</strong>re at first (and <strong>of</strong>ten subsequently—see <strong>the</strong> bitter sonnet that he chose not to publish,<br />

‘Lines on Cambridge <strong>of</strong> 1830’): ‘<strong>The</strong> country is so disgustingly level, <strong>the</strong> revelry <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> place so monotonous,<br />

<strong>the</strong> studies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University so uninteresting, so much matter <strong>of</strong> fact—none but dryheaded calculating<br />

angular little gentlemen can take much delight’ in algebraic formulae (18 April 1828, Letters, 1.23). But<br />

fortunately he came to know some well‐rounded larger gentlemen, foremost among <strong>the</strong>m Arthur Henry<br />

Hallam (1811–1833) [see under Hallam, Henry (1777–1859)], whom Tennyson met about April 1829. Hallam<br />

had entered Trinity College <strong>the</strong> previous October. <strong>The</strong> friendship, deepening into love, <strong>of</strong> Hallam and<br />

Tennyson was to be one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most important experiences <strong>of</strong> Hallamʹs short life and <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs long one.<br />

A fur<strong>the</strong>r flowering at Cambridge: in October 1829 Tennyson was elected a member <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Apostles, an<br />

informal debating society to which most <strong>of</strong> his Cambridge friends belonged (such eminent, though not pre‐<br />

eminent, Victorians as John Kemble, Richard Chenevix Trench, Richard Monckton Milnes, and James<br />

Spedding). <strong>The</strong>n in June 1829 he won <strong>the</strong> chancellorʹs gold medal with his prize poem on <strong>the</strong> set subject<br />

Timbuctoo. Reworking an earlier poem (as he was so <strong>of</strong>ten to do with consummate re‐creative imagination),

this on Armageddon, ‘altering <strong>the</strong> beginning and <strong>the</strong> end’ to bend it on Timbuctoo, ‘I was never so surprised<br />

as when I got <strong>the</strong> prize’ (Lincoln MS, ‘Materials for a Life <strong>of</strong> A. T.’; H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.355) . <strong>The</strong><br />

surprise was <strong>the</strong> greater in that <strong>the</strong> winning poem was, unprecedentedly, not in heroic couplets but in blank<br />

verse. At <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poem is a mystical trance such as fascinated Tennyson lifelong. Hallam, happily<br />

worsted, wrote with characteristic generosity and acumen: ‘<strong>The</strong> splendid imaginative power that pervades it<br />

will be seen through all hindrances. I consider Tennyson as promising fair to be <strong>the</strong> greatest poet <strong>of</strong> our<br />

generation, perhaps <strong>of</strong> our century’ (A. H. Hallam to Gladstone, 14 Sept 1829, Letters <strong>of</strong> Arthur Henry<br />

Hallam, 319).<br />

<strong>The</strong>n in December 1829 (or, it may be, April 1830), Hallam met Tennysonʹs sister Emily, with whom he was<br />

soon to fall in love. In <strong>the</strong> summer <strong>of</strong> 1830 Tennyson visited <strong>the</strong> Pyrenees with Hallam. (More than thirty<br />

years later, in June 1861, Tennyson was to return <strong>the</strong>re with his family and to write ‘In <strong>the</strong> Valley <strong>of</strong><br />

Cauteretz’, in lasting love <strong>of</strong> Hallam.) Hallam and Tennyson were to visit <strong>the</strong> Rhine country in <strong>the</strong> summer<br />

<strong>of</strong> 1832. In <strong>the</strong> autumn <strong>of</strong> 1832 <strong>the</strong> engagement <strong>of</strong> Hallam to Tennysonʹs sister was to be reluctantly<br />

recognized by Hallamʹs family.<br />

Poems, Chiefly Lyrical was published by Effingham Wilson in June 1830; some <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs most enduring<br />

notes, elegiacally lyrical, with his riven sensibility (‘Supposed Confessions <strong>of</strong> a Second‐Rate Sensitive Mind<br />

Not at Unity with Itself’), are especially manifest in <strong>the</strong> volumeʹs most remarkable achievements, ‘Mariana’,<br />

‘A spirit haunts <strong>the</strong> yearʹs last hours’, and ‘<strong>The</strong> Kraken’.<br />

Tennysonʹs fa<strong>the</strong>r, after marital separation and <strong>the</strong>n a return to protracted illness and weakness, died in<br />

March 1831. Tennyson left Cambridge without taking a degree. His choice <strong>of</strong> life? His uncle Charles wrote<br />

on 18 May 1831 to Tennysonʹs grandfa<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> Old Man <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wolds:<br />

We discussed what was to be done with <strong>the</strong> Children. Alfred is at home, but wishes to return to<br />

Cambridge to take a degree. I told him it was a useless expense unless he meant to go into <strong>the</strong> Church. He<br />

said he would. I did not think he seemed much to like it. I <strong>the</strong>n suggested Physic or some o<strong>the</strong>r Pr<strong>of</strong>ession.<br />

He seemed to think <strong>the</strong> Church <strong>the</strong> best and has I think finally made up his mind to it. <strong>The</strong> Tealby Living<br />

was mentioned and understood to be intended for him.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n, reverting to <strong>the</strong> matter: ‘Alfred seems quite ready to go into <strong>the</strong> Church although I think his mind is<br />

fixed on <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> deriving his great distinction and greatest means <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> exercise <strong>of</strong> his poetic talents’<br />

(Letters, 1.59–61).<br />

Poetic talents needed <strong>the</strong> support <strong>of</strong> financial talents. Fortunately, <strong>from</strong> his aunt Russell he received £100 a<br />

year (this continued into <strong>the</strong> 1850s), and when his grandfa<strong>the</strong>r died in 1835, <strong>the</strong>re came to Tennyson about<br />

£6000. Even though most <strong>of</strong> this was lost in a bad investment, <strong>the</strong>re was to be <strong>the</strong> civil‐list pension <strong>of</strong> £200 a<br />

year that began in 1845 (he drew it until he died), and his straits were never as dire as he liked to maintain.<br />

<strong>The</strong> poetic talents were Arthur Hallamʹs focus in <strong>the</strong> Englishmanʹs Magazine, in August 1831: ‘On Some <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Characteristics <strong>of</strong> Modern Poetry, and on <strong>the</strong> Lyrical Poems <strong>of</strong> Alfred Tennyson’. W. B. Yeats was to<br />

praise this essay as<br />

criticism which is <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> best and rarest sort. If one set aside Shelleyʹs essay on poetry and Browningʹs<br />

essay on Shelley, one does not know where to turn in modern English criticism for anything so<br />

philosophic—anything so fundamental and radical—as <strong>the</strong> first half<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hallamʹs piece (<strong>The</strong> Speaker, 22 July 1893; Yeats, 277) . Of Tennysonʹs art, Hallamʹs essay remains <strong>the</strong> most<br />

compactly telling evocation, prescient too. Hallam limned five characteristics:

First, his luxuriance <strong>of</strong> imagination, and at <strong>the</strong> same time his control over it. Secondly his power <strong>of</strong><br />

embodying himself in ideal characters, or ra<strong>the</strong>r moods <strong>of</strong> character, with such extreme accuracy <strong>of</strong><br />

adjustment, that <strong>the</strong> circumstances <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> narration seem to have a natural correspondence with <strong>the</strong><br />

predominant feeling, and, as it were, to be evolved <strong>from</strong> it by assimilative force. Thirdly his vivid,<br />

picturesque delineation <strong>of</strong> objects, and <strong>the</strong> peculiar skill with which he holds all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m fused, to borrow a<br />

metaphor <strong>from</strong> science, in a medium <strong>of</strong> strong emotion. Fourthly, <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> his lyrical measures, and<br />

exquisite modulation <strong>of</strong> harmonious words and cadences to <strong>the</strong> swell and fall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> feelings expressed.<br />

Fifthly, <strong>the</strong> elevated habits <strong>of</strong> thought, implied in <strong>the</strong>se compositions, and imparting a mellow soberness <strong>of</strong><br />

tone, more impressive, to our minds, than if <strong>the</strong> author had drawn up a set <strong>of</strong> opinions in verse, and sought<br />

to instruct <strong>the</strong> understanding ra<strong>the</strong>r than to communicate <strong>the</strong> love <strong>of</strong> beauty to <strong>the</strong> heart. (Jump, 42)<br />

Hallamʹs acute praise was welcome but not to everybody—Tennyson was already becoming ‘<strong>the</strong> Pet <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Coterie’, according to Christopher North (John Wilson) in Blackwoodʹs Magazine in May 1832 (Jump, 50). In<br />

February 1832 <strong>the</strong> notoriously scathing Christopher North had praised Tennyson highly, albeit with caveats,<br />

in Blackwoodʹs, but <strong>the</strong>n in May he followed this with a wittily severe—not indiscriminate—review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

1830 volume, this to ‘save him <strong>from</strong> his worst enemies, his friends’ (Jump, 51). Tennyson, pricked though not<br />

bridled by such reviewers, was exacerbatedly thin‐skinned and always self‐critical, <strong>of</strong>ten revising talent into<br />

genius—or expunging: <strong>the</strong> volume <strong>of</strong> 1830 included twenty‐three poems that he did not subsequently<br />

reprint, as well as seven not collected in his two‐volume Poems (1842) though reprinted later. <strong>The</strong> poems <strong>of</strong><br />

1830 that he did reprint, he—unusually—grouped as ‘Juvenilia’, justly in some cases, unjustly (protectively)<br />

for such a great poem as ‘Mariana’.<br />

Fertile, Tennyson issued in December 1832 Poems (published by Edward Moxon, <strong>the</strong> title‐page dated 1833).<br />

Among its feats were ‘<strong>The</strong> Lady <strong>of</strong> Shalott’, ‘Mariana in <strong>the</strong> South’, ‘Œnone’, ‘<strong>The</strong> Palace <strong>of</strong> Art’, ‘<strong>The</strong> Lotos‐<br />

Eaters’, and ‘A Dream <strong>of</strong> Fair Women’. <strong>The</strong>re were some failures subsequently acknowledged: seven poems<br />

never reprinted, and seven not collected in Poems (1842) though reprinted later. A venomous review by J.<br />

W. Croker (Quarterly Review, April 1833) drew blood but was a spur: <strong>the</strong> best <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poems were to be made<br />

even better, duly revised for republication, ten years later, but <strong>the</strong> painful rewording process began at once.<br />

As his Cambridge friend Edward FitzGerald wrote on 25 October 1833:<br />

Tennyson has been in town for some time: he has been making fresh poems, which are finer, <strong>the</strong>y say,<br />

than any he has done. But I believe he is chiefly meditating on <strong>the</strong> purging and subliming <strong>of</strong> what he has<br />

already done: and repents that he has published at all yet. It is fine to see how in each succeeding poem <strong>the</strong><br />

smaller ornaments and fancies drop away, and leave <strong>the</strong> grand ideas single. (Letters <strong>of</strong> Edward FitzGerald,<br />

1.140)<br />

It is heartening that in October 1833 Tennyson could be so actively creative in new and newly improved<br />

poems. For it was on 1 October that <strong>the</strong>re was sent to him <strong>the</strong> news <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sudden death <strong>of</strong> Arthur Hallam,<br />

stricken on 15 September by apoplexy while visiting Vienna. His body was brought back by sea to Clevedon,<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Bristol Channel, ‘Among familiar names to rest’, ‘And in <strong>the</strong> hearing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wave’ (In Memoriam,<br />

XVIII and XIX).<br />

<strong>The</strong> blow, not to Tennyson alone, but to his sister Emily, to both families, and to Hallamʹs many friends and<br />

admirers, was pr<strong>of</strong>ound, ‘a loud and terrible stroke’ (reported <strong>the</strong> Cambridge friend Charles Merivale) ‘<strong>from</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> reality <strong>of</strong> things upon <strong>the</strong> faery building <strong>of</strong> our youth’ (<strong>from</strong> H. Alford, 11 Nov 1833, Merivale, 135). <strong>The</strong><br />

sense <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tennyson family loss is audible in a letter by Frederick <strong>of</strong> 18 December 1833:<br />

We all looked forward to his society and support through life in sorrow and in joy, with <strong>the</strong> fondest hopes,<br />

for never was <strong>the</strong>re a human being better calculated to sympathize with and make allowance for those<br />

peculiarities <strong>of</strong> temperament and those failings to which we are liable. (Letters, 1.104)

Yet in <strong>the</strong> first stricken month, Tennyson set to write poems that later became some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> finest sections <strong>of</strong><br />

In Memoriam (<strong>the</strong> earliest is dated 6 October 1833, none being published until seventeen years after Hallamʹs<br />

death), as well as soon drafting ‘Ulysses’, ‘Morte dʹArthur’, and ‘Tithonus’ (this last not published until 1860,<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two 1842)—three great poems prompted by <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> his Arthur, and all finding extraordinarily<br />

compelling correlatives, in ancient worlds, for his feelings personal and universal, ancient and modern.<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> Two Voices’ belongs to 1833, and was said by Tennysonʹs son to have been ‘begun under <strong>the</strong> cloud <strong>of</strong><br />

this overwhelming sorrow, which, as my fa<strong>the</strong>r told me, for a while blotted out all joy <strong>from</strong> his life, and<br />

made him long for death’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.109). But Tennyson had longed for death before Hallam<br />

died, and a draft <strong>of</strong> ‘<strong>The</strong> Two Voices’ was in existence three months earlier, in June 1833, when his friend J.<br />

M. Kemble wrote to W. B. Donne:<br />

Next Sir are some superb meditations on Self destruction called Thoughts <strong>of</strong> a Suicide wherein he argues<br />

<strong>the</strong> point with his soul and is thoroughly floored. <strong>The</strong>se are amazingly fine and deep, and show a mighty<br />

stride in intellect since <strong>the</strong> Second‐Rate Sensitive Mind. (Poems, 1.570)<br />

Suicide appears, <strong>of</strong>ten enacted and sometimes discussed, in an extraordinary number <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs poems<br />

over <strong>the</strong> years, where it is complemented not only by suicidal risks but by martyrs and by <strong>the</strong> military (as in<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> Charge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Light Brigade’). Mary Gladstone was to record ‘a plan he had <strong>of</strong> writing a satire called “A<br />

suicide supper”’, and that Tennyson ‘would commit suicide’ if he believed that death were annihilation<br />

(Mary Gladstone, 8 June 1879, 160).<br />

On 14 February 1834 Tennyson replied to a request <strong>from</strong> Hallamʹs fa<strong>the</strong>r to contribute to a memorial volume:<br />

I attempted to draw up a memoir <strong>of</strong> his life and character, but I failed to do him justice. I failed even to<br />

please myself. I could scarcely have pleased you. I hope to be able at a future period to concentrate whatever<br />

powers I may possess on <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> some tribute to those high speculative endowments and<br />

comprehensive sympathies which I ever loved to contemplate; but at present, though somewhat ashamed at<br />

my own weakness, I find <strong>the</strong> object yet is too near me to permit <strong>of</strong> any very accurate delineation. You, with<br />

your clear insight into human nature, may perhaps not wonder that in <strong>the</strong> dearest service I could have been<br />

employed in, I should be found most deficient. (Letters, 1.108)<br />

In Memoriam A.H.H. (1850) was duly to render such dearest service—to Hallam, to Tennyson himself, and<br />

to all his readers <strong>the</strong>n and since, to all those who, like Queen Victoria and whatever <strong>the</strong>ir beliefs, have found,<br />

in its mourning and in its recovery, lasting consolation.<br />

Tennyson, afraid (with good cause) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spite which—like Keats before him, and similarly with some class<br />

animus—he precipitated in reviewers, tried in 1834 to placate Christopher North, and tried in early March<br />

1835 to discourage John Stuart Mill <strong>from</strong> writing about <strong>the</strong> poems.<br />

I do not wish to be dragged forward again in any shape before <strong>the</strong> reading public at present, particularly<br />

on <strong>the</strong> score <strong>of</strong> my old poems most <strong>of</strong> which I have so corrected (particularly Œnone) as to make <strong>the</strong>m much<br />

less imperfect. (To James Spedding, Letters, 1.130)<br />

Fortunately, Mill went ahead, and discerningly praised in Tennyson<br />

<strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> creating scenery, in keeping with some state <strong>of</strong> human feeling; so fitted to it as to be <strong>the</strong><br />

embodied symbol <strong>of</strong> it, and to summon up <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> feeling itself, with a force not to be surpassed by<br />

anything but reality. (London Review, July 1835; Jump, 86)<br />

Love, marriage, and lifelong faith

It was in 1834 that Tennyson fell in love with Rosa Baring, <strong>of</strong> Harington Hall, 2 miles <strong>from</strong> Somersby. It was<br />

to be a brief and frustrated love (she was rich, she was a Baring, she was—it seems—a coquette), but it was<br />

never to fade <strong>from</strong> his memory. It was less <strong>the</strong> joys <strong>of</strong> this young romance than <strong>the</strong> pains <strong>of</strong> disillusionment,<br />

following promptly in 1835–6, that had a lastingly valuable presence within his writing, for <strong>the</strong> pressures <strong>of</strong><br />

social snobbery—long known <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tennyson v. Tennyson‐DʹEyncourt feud—and <strong>of</strong> ‘<strong>The</strong> rentroll Cupid<br />

<strong>of</strong> our rainy isles’ (‘Edwin Morris’), ‘This filthy marriage‐hindering Mammon’ (‘Aylmerʹs Field’), are acidly<br />

etched in ‘Locksley Hall’, ‘Edwin Morris’, and Maud, all written or inaugurated between 1837 and 1839.<br />

Tennyson was <strong>the</strong> better able to gauge this amatory excitement <strong>of</strong> his because <strong>of</strong> his soon coming to love,<br />

deeply, Emily Sellwood [see Tennyson, Emily Sarah (1813–1896)]. He had first met her in 1830, <strong>the</strong> daughter<br />

<strong>of</strong> a solicitor in Horncastle (5 miles <strong>from</strong> Somersby). In May 1836 Emilyʹs sister Louisa married Tennysonʹs<br />

older bro<strong>the</strong>r Charles (now curate <strong>of</strong> Tealby in Lincolnshire), and Tennyson was to date his love for Emily<br />

<strong>from</strong> this wedding, where he glimpsed <strong>the</strong> happy bridesmaid as his future happy bride. In 1838 <strong>the</strong><br />

engagement was recognized by her family and his, but was broken <strong>of</strong>f in 1840, partly because <strong>of</strong> financial<br />

insecurity (‘owing to want <strong>of</strong> funds’, <strong>the</strong>ir son was to write (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.150)), but also because<br />

<strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs religious unorthodoxy and spiritual perturbation. It was not until 1849 that his<br />

correspondence with Emily was renewed. <strong>The</strong>n <strong>the</strong> honest faith and <strong>the</strong> honest doubt evinced within In<br />

Memoriam (to be published in May 1850) played a large part in overcoming Emilyʹs doubts, and she and <strong>the</strong><br />

poet were wed on 13 June 1850. <strong>The</strong> service was at Shiplake‐on‐Thames where Tennysonʹs friend<br />

Drummond Rawnsley was vicar.<br />

This was to be a happy marriage, clearly seen in ‘<strong>The</strong> Daisy’, about Tennysonʹs visit to Italy with Emily in<br />

1851 (a delayed honeymoon), and in <strong>the</strong> lovely late tribute, ‘June Bracken and Hea<strong>the</strong>r’, written in 1891, <strong>the</strong><br />

year before he died, and constituting <strong>the</strong> dedication <strong>of</strong> his final and posthumous volume. Equably<br />

hierarchical and reciprocally loving, warmly embracing <strong>the</strong> double duty <strong>of</strong> family claims and <strong>the</strong> claims <strong>of</strong><br />

art, <strong>the</strong>ir life toge<strong>the</strong>r was a joy. It was sadly darkened by <strong>the</strong> stillbirth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir first child on 20 April 1851,<br />

and by <strong>the</strong> grievous loss <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir son Lionel (b. 16 March 1854), dead in his thirties (April 1886), but it was<br />

blessed with <strong>the</strong> lifelong self‐abnegating dedication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir son Hallam Tennyson (1852–1928). <strong>The</strong>ir home<br />

was at first Chapel House, Montpelier Row, Twickenham. In November 1853 <strong>the</strong>y moved to Farringford<br />

(Freshwater, Isle <strong>of</strong> Wight), which Tennyson bought in 1856. Among <strong>the</strong> many notable visitors to<br />

Farringford was Garibaldi, in April 1864. In April 1868 <strong>the</strong> foundation stone was laid <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs second<br />

home, Aldworth, near Haslemere.<br />

Emily Tennyson was judged incomparable by Edward Lear:<br />

I should think, computing moderately, that 15 angels, several hundreds <strong>of</strong> ordinary women, many<br />

philosophers, a heap <strong>of</strong> truly wise & kind mo<strong>the</strong>rs, 3 or 4 minor prophets, & a lot <strong>of</strong> doctors and school‐<br />

mistresses, might all be boiled down, & yet <strong>the</strong>ir combined essence fall short <strong>of</strong> what Emily Tennyson really<br />

is. (2 June 1859, Noakes, 167)<br />

More two‐edgedly, FitzGerald granted that she was<br />

a Lady <strong>of</strong> a Shakespearian type, as I think AT once said <strong>of</strong> her: that is, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Imogen sort, far more<br />

agreeable to me than <strong>the</strong> sharp‐witted Beatrices, Rosalinds, etc. I do not think she has been (on this very<br />

account perhaps) as good a helpmate to ATʹs Poetry as to himself. (7 Dec 1869, Letters <strong>of</strong> Edward FitzGerald,<br />

3.177)<br />

Benjamin Jowett praised her: ‘overflowing with kindness—but also in a certain way very strong’, ‘his friend,<br />

his servant, his guide, his critic’. ‘It was a wonderful life—an effaced life like that <strong>of</strong> so many women’<br />

(Harvard MS, Catalogue, 19–20). ‘One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most beautiful, <strong>the</strong> purest, <strong>the</strong> most innocent, <strong>the</strong> most<br />

disinterested persons whom I have ever known’: ‘she was probably her husbandʹs best critic, and certainly<br />

<strong>the</strong> one whose authority he would most willingly have recognized’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.466–7).

His wife was <strong>of</strong> unique importance to Tennysonʹs religious self. She trusted Charles Kingsley, who in<br />

September 1850 described In Memoriam as<br />

altoge<strong>the</strong>r rivalling <strong>the</strong> sonnets <strong>of</strong> Shakespeare.—Why should we not say boldly, surpassing—for <strong>the</strong> sake<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> superior faith into which it rises, for <strong>the</strong> sake <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> proem at <strong>the</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> volume—in our eyes,<br />

<strong>the</strong> noblest English Christian poem which several centuries have seen? (Fraserʹs Magazine; Jump, 183)<br />

Aubrey de Vere characterized Emily, a few months after <strong>the</strong> marriage:<br />

Her great and constant desire is to make her husband more religious, or at least to conduce, as far as she<br />

may, to his growth in <strong>the</strong> spiritual life. In this she will doubtless succeed, for piety like hers is infectious,<br />

especially where <strong>the</strong>re is an atmosphere <strong>of</strong> affection to serve as a conducting medium. Indeed I already<br />

observe a great improvement in Alfred. His nature is a religious one, and he is remarkably free <strong>from</strong> vanity<br />

and sciolism. Such a nature gravitates towards Christianity, especially when it is in harmony with itself. (14<br />

Oct 1850, Ward, 158–9)<br />

Gruffer, <strong>the</strong>re are Tennysonʹs words to Gladstoneʹs daughter Mary (4 June 1879): ‘We shall all turn into pigs<br />

if we lose Christianity and God’ (Mary Gladstone, 157). ‘T. loves <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> Christianity, hates many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

dogmas’, reported William Allingham in January 1867 (Allingham, 149). He respected <strong>the</strong> breadth and<br />

latitude <strong>of</strong> F. D. Maurice. In October 1853 Maurice was forced to resign <strong>from</strong> his pr<strong>of</strong>essorship in London for<br />

arguing that <strong>the</strong> popular belief in <strong>the</strong> endlessness <strong>of</strong> future punishment was superstitious. Tennyson<br />

abominated <strong>the</strong> belief in eternal torment, and he had recently asked Maurice (who had agreed) to be<br />

godfa<strong>the</strong>r to Hallam Tennyson. ‘To <strong>the</strong> Rev. F. D. Maurice’ is a verse invitation that glowingly revives <strong>the</strong><br />

Horatian epistle, and bears comparison with such classics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> kind as Ben Jonsonʹs ‘Inviting a Friend to<br />

Supper’.<br />

In April 1869 Tennyson attended <strong>the</strong> meeting to organize <strong>the</strong> Metaphysical Society, which he joined and<br />

which flourished until 1879. In his seventies he said to Allingham, in July 1884: ‘Youʹre not orthodox, and I<br />

canʹt call myself orthodox. Two things however I have always been firmly convinced <strong>of</strong>—God,—and that<br />

death will not end my existence’ (Allingham, 329). <strong>The</strong> very late poems, ‘<strong>The</strong> Ancient Sage’ (1885), on Lao‐<br />

Tse, and ‘Akbarʹs Dream’ (1892), on what was <strong>the</strong>n called Mohammedanism, seek to realize—under <strong>the</strong><br />

influence <strong>of</strong> Benjamin Jowett—‘<strong>The</strong> religions <strong>of</strong> all good men’, in support <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conviction that ‘All religions<br />

are one’.<br />

Two months before he died, Tennyson talked with John Addington Symonds:<br />

He told me he was going to write a poem on Bruno, and asked what I thought about his [Brunoʹs] attitude<br />

toward Christianity. I tried to express my views, and Hallam got up and showed me that <strong>the</strong>y were reading<br />

up <strong>the</strong> chapter <strong>of</strong> my ‘Renaissance in Italy’ on Bruno. Tennyson observed that <strong>the</strong> great thing in Bruno was<br />

his perception <strong>of</strong> an Infinite Universe, filled with solar systems like our own, and all penetrated with <strong>the</strong><br />

Soul <strong>of</strong> God. ‘That conception must react destructively on Christianity—I mean its creed and dogma—its<br />

morality will always remain.’ Somebody had told him that astronomers could count 550 million solar<br />

systems. He observed that <strong>the</strong>re was no reason why each should not have planets peopled with living and<br />

intelligent beings. ‘<strong>The</strong>n,’ he added, ‘see what becomes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> second person <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Deity, and <strong>the</strong> sacrifice <strong>of</strong><br />

a God for fallen man upon this little earth!’ (29 Aug 1892, Letters <strong>of</strong> John Addington Symonds, 3.744)<br />

From Poems (1842) to <strong>The</strong> Princess (1847)<br />

Between 1832 and 1842 Tennyson published no volume‐length work. <strong>The</strong> span has been mildly<br />

melodramatized into ‘<strong>the</strong> ten yearsʹ silence’, but he wrote much during this period, founding and building In<br />

Memoriam, creating his exquisite ‘English Idyls’ (most notably, ‘Edwin Morris’ and ‘<strong>The</strong> Golden Year’), and<br />

he rewrote with depth and passion. At <strong>the</strong> urging <strong>of</strong> his friend Richard Monckton Milnes, he reluctantly sent

to <strong>The</strong> Tribute (September 1837) a true though as yet unperfected poem, ‘Oh! that ʹtwere possible’, which<br />

was to be ‘<strong>the</strong> germ’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> amazing monodrama <strong>of</strong> madness, Maud (1855).<br />

Life was taxing. On <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> Dr Tennyson in 1831 <strong>the</strong> family had been allowed by <strong>the</strong> incoming rector to<br />

continue to live in <strong>the</strong> rectory at Somersby, but <strong>the</strong>n, in 1837, <strong>the</strong>y had to move to High Beech, Epping<br />

Forest. ‘His two elder bro<strong>the</strong>rs being away’ (Frederick in Corfu and <strong>the</strong>n Florence—for good; and Charles<br />

settled at Grasby, Lincolnshire), it was on Alfred that <strong>the</strong>re ‘devolved <strong>the</strong> care <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family and <strong>of</strong> choosing<br />

a new home’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.149–50; ‘My mo<strong>the</strong>r is afraid if I go to town even for a night; how<br />

could <strong>the</strong>y get on without me for months?’, to Emily Sellwood, 10 July 1839, Letters, 1.171) . <strong>The</strong>n in 1840<br />

<strong>the</strong>y had to move to Tunbridge Wells, and in 1841 to Boxley, near Maidstone. <strong>The</strong> engagement to Emily<br />

Sellwood was broken <strong>of</strong>f in 1840. <strong>The</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re was <strong>the</strong> investing by Tennyson in 1840–41 <strong>of</strong> his invaluable<br />

small fortune (about £3000) in a scheme for wood‐carving by machinery, which had collapsed by 1843. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

were among <strong>the</strong> things that made much <strong>of</strong> life a misery. ‘I have drunk one <strong>of</strong> those most bitter draughts out<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cup <strong>of</strong> life, which go near to make men hate <strong>the</strong> world <strong>the</strong>y move in’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.221).<br />

FitzGerald reported <strong>of</strong> Tennyson, to Tennysonʹs bro<strong>the</strong>r Frederick, on 10 December 1843 that he had ‘never<br />

seen him so hopeless’ (Letters <strong>of</strong> Edward FitzGerald, 1.408). In 1843–4 Tennyson received treatment.<br />

<strong>The</strong> perpetual panic and horror <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> last two years has steeped my nerves in poison: now I am left a<br />

beggar but I am or shall be shortly somewhat better <strong>of</strong>f in nerves. I am in a Hydropathy Establishment near<br />

Cheltenham (<strong>the</strong> only one in England conducted on pure Priessnitzan principles) … Much poison has come<br />

out <strong>of</strong> me, which no physic ever would have brought to light. (To FitzGerald, 2 Feb 1844, Letters, 1.222–3)<br />

<strong>The</strong> hydropathy was endured near Cheltenham; Tennyson <strong>the</strong>n lived, first, at 6 Bellevue Place, and <strong>the</strong>n at<br />

10 St Jamesʹs Square, Cheltenham.<br />

In an unpublished poem (‘Wherefore, in <strong>the</strong>se dark ages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Press’), Tennyson spoke <strong>of</strong> ‘this Art‐<br />

Conscience’, a surety which, along with courage, steadied and secured him. This, with more than a little help<br />

<strong>from</strong> his friends, who encouraged him, pressed him. On 3 March 1838: ‘Do you ever see Tennyson? and if so,<br />

could you not urge him to take <strong>the</strong> field?’ (R. C. Trench to R. M. Milnes, Reid, 1.208). ‘Tennyson composes<br />

every day, but nothing will persuade him to print, or even write it down’ (Milnes, 1838, Reid, 1.220).<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r Cambridge friend, G. S. Venables, urged him in August/September 1838:<br />

Do not continue to be so careless <strong>of</strong> fame and <strong>of</strong> influence. You have abundant materials ready for a new<br />

publication, and you start as a well‐known man with <strong>the</strong> certainty that you can not be overlooked, and that<br />

by many you will be appreciated. If you do not publish now when will you publish? (Letters, 1.163–4)<br />

On 25 November 1839 FitzGerald all but gave up:<br />

I want A. T. to publish ano<strong>the</strong>r volume: as all his friends do: especially Moxon, who has been calling on<br />

him for <strong>the</strong> last two years for a new edition <strong>of</strong> his old volume: but he is too lazy and wayward to put his<br />

hand to <strong>the</strong> business. (Letters <strong>of</strong> Edward FitzGerald, 1.239)<br />

<strong>The</strong>n <strong>the</strong>re was <strong>the</strong> American threat. To <strong>the</strong> importunate FitzGerald Tennyson wrote c.22 February 1841:<br />

‘You bore me about my book: so does a letter just received <strong>from</strong> America, threatening, though in <strong>the</strong> civilest<br />

terms that if I will not publish in England <strong>the</strong>y will do it for me in that land <strong>of</strong> freemen’ (Letters, 1.188). Long<br />

after, to Allingham, Tennyson recalled this provocation:<br />

I hate publishing! <strong>The</strong> Americans forced me into it again. I had my things nice and right, but when I found<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were going to publish <strong>the</strong> old forms I said, By Jove, that wonʹt do!—My whole living is <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> sale <strong>of</strong><br />

my books. (Allingham, 168, 27 Dec 1867)

So at last, in May 1842, Tennyson issued Poems (Moxon). <strong>The</strong> first volume selected <strong>the</strong> best <strong>of</strong> 1830 and 1832,<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with a few poems written c.1833; <strong>the</strong> second volume consisted <strong>of</strong> new poems, some soon famous,<br />

such as ‘Locksley Hall’, and some among his greatest: ‘Morte dʹArthur’, ‘Ulysses’, ‘Break, break, break’, and<br />

‘St Simeon Stylites’.<br />

By June 1845 Tennyson had set to work on his long poem about university education for women, <strong>The</strong><br />

Princess. <strong>The</strong> plan had formed in 1839, at a time when <strong>the</strong>re was in Cambridge and elsewhere a renewed<br />

sympathy with womenʹs claims, one that remembered Mary Wollstonecraftʹs Vindication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rights <strong>of</strong><br />

Woman (1792) and gained a new impetus <strong>from</strong> Anna Jamesonʹs Characteristics <strong>of</strong> Women (1832), later<br />

known as Shakespeareʹs Heroines. Jameson herself acknowledged many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> old ideals <strong>of</strong> womanhood.<br />

What marriage would be, once womenʹs intellectual rights were respected: this was <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> central woman<br />

question. Tennysonʹs poem, ever apt, is a vivid reflection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ageʹs humanely troubled concern. Like<br />

Tennyson himself, it is liberal in spirit, conservative in upshot. Progressive, perhaps, for as T. S. Eliot said <strong>of</strong><br />

Whitman and Tennyson, ‘Both were conservative, ra<strong>the</strong>r than reactionary or revolutionary; that is to say,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y believed explicitly in progress, and believed implicitly that progress consists in things remaining much<br />

as <strong>the</strong>y are’ (T. S. Eliot, ‘Whitman and Tennyson’).<br />

FitzGerald divined that this new poem was both a symptom and a cause <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs improved state <strong>of</strong><br />

mind. In September 1845, through <strong>the</strong> good <strong>of</strong>fices <strong>of</strong> (among o<strong>the</strong>rs) Henry Hallam, Tennyson was granted<br />

by Sir Robert Peel a civil‐list pension <strong>of</strong> £200 a year, for life. <strong>The</strong> following year, with his publisher Edward<br />

Moxon, he visited Switzerland (August 1846), ‘<strong>the</strong> stateliest bits <strong>of</strong> landskip I ever saw’ (A. Tennyson to<br />

FitzGerald, 12 Nov 1846, Letters, 1.264). <strong>The</strong> mountainscape was soon to rise within <strong>The</strong> Princess (published<br />

December 1847).<br />

FitzGerald thought <strong>The</strong> Princess ‘a wretched waste <strong>of</strong> power at a time <strong>of</strong> life when a man ought to be doing<br />

his best’ (FitzGerald to Frederick Tennyson, 4 May 1848, Letters <strong>of</strong> Edward FitzGerald, 1.604). Carlyle was<br />

even less sympa<strong>the</strong>tic: ‘very gorgeous, fervid, luxuriant, but indolent, somnolent, almost imbecil’ (25 Dec<br />

1847, Collected Letters, 22.183). Yet here are three <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs finest lyrics—‘Tears, idle tears’, ‘Now sleeps<br />

<strong>the</strong> crimson petal, now <strong>the</strong> white’, and ‘Come down, O maid, <strong>from</strong> yonder mountain height’. <strong>The</strong> Prologue<br />

presents a group <strong>of</strong> young friends at a country‐house fête; <strong>the</strong>y speak <strong>of</strong> womenʹs rights, and <strong>the</strong>n tell, each<br />

in turn (‘a sevenfold story’; ‘Prologue’, 198) , <strong>the</strong> tale <strong>of</strong> a princess who founds a university for women; her<br />

plans are broken by an irruption <strong>of</strong> men and <strong>the</strong>n by an eruption <strong>of</strong> love. Tennysonʹs subtitle, ‘A Medley’, is<br />

truthful, and defensive. <strong>The</strong> poem, locally fine, is happy not to have to be a whole, whe<strong>the</strong>r politically or<br />

personally. It was for <strong>the</strong> poet a relief and a release <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> pains <strong>of</strong> his 1840s. He duly felt obliged to recast<br />

it more substantially than any o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>of</strong> his long poems.<br />

In 1848 Tennyson visited Ireland and Cornwall, taking up again a projected Arthurian enterprise, and in<br />

1849 <strong>the</strong> correspondence with Emily Sellwood was renewed. Tennyson now was granted his annus<br />

mirabilis. For 1850 was to see, first, <strong>the</strong> publication <strong>of</strong> In Memoriam (anonymously, in <strong>the</strong> last week <strong>of</strong> May);<br />

next, his wedding, in June; and <strong>the</strong>n in November his appointment as poet laureate.<br />

Hereafter Tennyson was to be, though he enjoyed denying it, secure. Secure in reputation, though <strong>the</strong><br />

passing judgements were sometimes harsh—‘that fierce light which beats upon a throne’ (Dedication to<br />

Idylls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> King) beats too upon <strong>the</strong> poetʹs throne. Secure, too, in finances: with strong sales and with<br />

publishers <strong>of</strong> integrity (Moxon through to Macmillan, with Ticknor doing <strong>the</strong> distinctly unusual thing for an<br />

American publisher <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time and honourably paying up), he stayed <strong>the</strong> course and stayed in print. In <strong>the</strong><br />

last year <strong>of</strong> his life he earned more than £10,000, and he left an estate worth more than £57,000 (Martin, 578).<br />

In Memoriam (1850)<br />

In 1842 Tennysonʹs sister Emily, after eight years <strong>of</strong> quasi‐widowed fidelity to Arthur Hallam, had married<br />

Captain Richard Jesse RN. Comments on this were harshly unjust, but Tennyson was not, and he gave his<br />

sister in marriage. He must, though, have been aware that <strong>the</strong> changed relation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tennysons to <strong>the</strong><br />

Hallams might cast a shadow on <strong>the</strong> poem that was becoming In Memoriam, which he chose not to publish

until 1850, when it closed with <strong>the</strong> wedding <strong>of</strong> a different sister <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs (Cecilia) to a family friend<br />

(Edmund Lushington) who could not but call up Arthur Hallam.<br />

Tennyson had written what became sections <strong>of</strong> In Memoriam within a month <strong>of</strong> Hallamʹs death (September<br />

1833).<br />

<strong>The</strong> sections were written at many different places, and as <strong>the</strong> phases <strong>of</strong> our intercourse came to my<br />

memory and suggested <strong>the</strong>m. I did not write <strong>the</strong>m with any view <strong>of</strong> weaving <strong>the</strong>m into a whole, or for<br />

publication, until I found that I had written so many. (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.304)<br />

On 30 November 1844 Tennyson wrote to his aunt Russell:<br />

With respect to <strong>the</strong> non‐publication <strong>of</strong> those poems which you mention, it is partly occasioned by <strong>the</strong><br />

considerations you speak <strong>of</strong>, and partly by my sense <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir present imperfectness: perhaps <strong>the</strong>y will not see<br />

<strong>the</strong> light till I have ceased to be. I cannot tell, but I have no wish to send <strong>the</strong>m out yet. (Letters, 1.231)<br />

On 29 January 1845 FitzGerald wrote to W. B. Donne:<br />

A. T. has near a volume <strong>of</strong> poems—elegiac—in memory <strong>of</strong> Arthur Hallam. Donʹt you think <strong>the</strong> world<br />

wants o<strong>the</strong>r notes than elegiac now? Lycidas is <strong>the</strong> utmost length an elegiac should reach. But Spedding<br />

[<strong>the</strong>ir Cambridge friend] praises: and I suppose <strong>the</strong> elegiacs will see daylight—public daylight—one day.<br />

(Letters <strong>of</strong> Edward FitzGerald, 1.478)<br />

<strong>The</strong> day dawned: it was in part <strong>the</strong> loving respect in which <strong>the</strong> poem (passed on to her, in manuscript or in<br />

pro<strong>of</strong>, by her cousin) was held by Emily Sellwood, soon to be Emily Tennyson, in April 1850 that fortified<br />

Tennysonʹs confidence in <strong>the</strong> poem that he published (anonymously) next month, and that was to win him,<br />

immediately and despite <strong>the</strong> mild fiction <strong>of</strong> anonymity, <strong>the</strong> laureateship and incontestable fame.<br />

Tennyson had used <strong>the</strong> octosyllabic quatrain rhyming abba in his patriotic poems <strong>of</strong> 1832–3.<br />

As for <strong>the</strong> metre <strong>of</strong> In Memoriam I had no notion till 1880 that Lord Herbert <strong>of</strong> Cherbury had written his<br />

occasional verses in <strong>the</strong> same metre. I believed myself <strong>the</strong> originator <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> metre, until after In Memoriam<br />

came out, when some one told me that Ben Jonson and Sir Philip Sidney had used it. (H. Tennyson, Memoir,<br />

1.305–6)<br />

(For 1880, read 1870; see letter <strong>of</strong> 8 August 1870, Letters, 2.553–4.)<br />

It is ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> cry <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> whole human race than mine. In <strong>the</strong> poem altoge<strong>the</strong>r private grief swells out into<br />

thought <strong>of</strong>, and hope for, <strong>the</strong> whole world. It begins with a funeral and ends with a marriage—begins with<br />

death and ends in promise <strong>of</strong> a new life—a sort <strong>of</strong> Divine Comedy, cheerful at <strong>the</strong> close. It is a very<br />

impersonal poem as well as personal. (Knowles, 182)<br />

George Eliot saw <strong>the</strong> poem under a different aspect: ‘Whatever was <strong>the</strong> immediate prompting <strong>of</strong> In<br />

Memoriam, whatever <strong>the</strong> form under which <strong>the</strong> author represented his aim to himself, <strong>the</strong> deepest<br />

significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poem is <strong>the</strong> sanctification <strong>of</strong> human love as a religion’ (Westminster Review, Oct 1855; G.<br />

Eliot, 191) .<br />

Both human love and divine love faced <strong>the</strong> challenge not only <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ages but <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> aeons. In ‘Parnassus’,<br />

written three years before he died, Tennyson was to imagine <strong>the</strong> two powers that were now seen to tower<br />

over all poetic aspirations: ‘<strong>The</strong>se are Astronomy and Geology, terrible Muses!’ In Memoriam did not stand<br />

in need <strong>of</strong> or in dread <strong>of</strong> Darwinʹs Origin <strong>of</strong> Species, for <strong>the</strong> poem preceded <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> science by nine<br />

years. Moreover Tennyson owed much not only to Charles Lyell and his Principles <strong>of</strong> Geology (1830–33),

which he mentioned to Milnes in 1836 (c.1 Nov, Letters, 1.145), but to William Buckland and his school <strong>of</strong><br />

thought. Yet In Memoriam became imaginatively central to <strong>the</strong> Darwinian evolutionary controversy, in a<br />

world where <strong>the</strong> Victorians feared that <strong>the</strong> ape in <strong>the</strong> zoo might suddenly ask ‘Am I my keeperʹs bro<strong>the</strong>r?’<br />

Tennyson threw <strong>of</strong>f epigrams that he did not publish, one being ‘Darwinʹs Gemmule’, and ano<strong>the</strong>r ‘By a<br />

Darwinian’ (both 1868), and he published ‘By an Evolutionist’ in 1889.<br />

By January 1851 In Memoriam was already in its fourth edition. Tennyson never issued an edition with his<br />

name on <strong>the</strong> title‐page, but <strong>from</strong> 1870 it appeared in collected editions <strong>of</strong> his works. <strong>The</strong> poem was to be on<br />

everyoneʹs lips and in most hearts, validating not only honest doubt but honest faith, a consolation <strong>of</strong><br />

philosophy for <strong>the</strong> age. In March 1889 F. W. H. Myers acknowledged what <strong>the</strong> poem had effected:<br />

It is hardly too much to say that In Memoriam is <strong>the</strong> only speculative book <strong>of</strong> that epoch—epoch <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

‘Tractarian movement’, and much similar ‘up‐in‐<strong>the</strong>‐air balloon‐work’—which retains a serious interest<br />

now. Its brief cantos contain <strong>the</strong> germs <strong>of</strong> many a subsequent treatise, <strong>the</strong> indication <strong>of</strong> channels along which<br />

many a wave <strong>of</strong> opinion has flowed, down to that last ‘Philosophie der Erlösung’, or Gospel <strong>of</strong> a sad<br />

Redemption—‘To drop head foremost in <strong>the</strong> jaws / Of vacant darkness, and to cease’—which tacitly or<br />

openly is possessing itself <strong>of</strong> so many a modern mind. (Nineteenth Century; Jump, 399)<br />

Queen Victoriaʹs poet laureate<br />

In November 1850 Tennyson was appointed poet laureate, Wordsworth having died in April (and Samuel<br />

Rogers having declined).<br />

<strong>The</strong> night before I was asked to take <strong>the</strong> Laureateship, which was <strong>of</strong>fered to me through Prince Albertʹs<br />

liking for my In Memoriam, I dreamed that he came to me and kissed me on <strong>the</strong> cheek. I said, in my dream,<br />

‘Very kind, but very German’. In <strong>the</strong> morning <strong>the</strong> letter about <strong>the</strong> Laureateship was brought to me and laid<br />

upon my bed. I thought about it through <strong>the</strong> day, but could not make up my mind whe<strong>the</strong>r to take it or<br />

refuse it, and at <strong>the</strong> last I wrote two letters, one accepting and one declining, and threw <strong>the</strong>m on <strong>the</strong> table,<br />

and settled to decide which I would send after my dinner and bottle <strong>of</strong> port. (Knowles, 167)<br />

Tennysonʹs character and his convictions (political and national), as well as his versatility, enabled him to be<br />

imaginatively duteous in <strong>the</strong> exercise <strong>of</strong> his responsibilities, <strong>the</strong> most felicitous <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>poets</strong> laureate. <strong>The</strong><br />

next year, <strong>the</strong>re followed his first such publication (dated March 1851), his deftly loving dedication, ‘To <strong>the</strong><br />

Queen’, heading <strong>the</strong> seventh edition <strong>of</strong> his Poems.<br />

Aware that <strong>the</strong> poet laureate should express his convictions but should also be careful not to harness his<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice to his own party political judgements, Tennyson on occasion published pseudonymously—for<br />

instance a run <strong>of</strong> patriotic poems during <strong>the</strong> invasion scare <strong>from</strong> France in early 1852. ‘Among <strong>the</strong> most<br />

enthusiastic national defenders are Alfred Tennyson and Mrs. A. T.’, wrote <strong>the</strong>ir friend Franklin Lushington<br />

on 8 February 1852:<br />

At least <strong>the</strong>y have been induced by Coventry Patmore to subscribe five pounds apiece for <strong>the</strong> purchase <strong>of</strong><br />

rifles to teach <strong>the</strong> world to shoot—which appears to me a ra<strong>the</strong>r exaggerated quota for <strong>the</strong> laureate to<br />

contribute out <strong>of</strong> his <strong>of</strong>ficial income, his duty being clearly confined to <strong>the</strong> howling <strong>of</strong> patriotic staves.<br />

(Letters, 2.26)<br />

Tennyson differentiated such staves <strong>from</strong> his first independent publication as laureate later <strong>the</strong> same year:<br />

his Ode on <strong>the</strong> Death <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Duke <strong>of</strong> Wellington (published on <strong>the</strong> day <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> funeral, 18 November 1852) is a<br />

noble four‐square paean, much called on in later years when a great national loss has been felt, as at <strong>the</strong><br />

death <strong>of</strong> Winston Churchill. Written, Tennyson insisted, <strong>from</strong> genuine admiration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> man, it was a true<br />

laureate ode, though not requested by <strong>the</strong> queen.

In January 1862 Tennyson published <strong>the</strong> verse dedication to open a new edition <strong>of</strong> Idylls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> King, in<br />

memory <strong>of</strong> Albert, prince consort, who had died in December 1861. (Tennyson was to conclude Idylls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

King, in <strong>the</strong> Imperial Library edition <strong>of</strong> 1873, with a complementary or married tribute, ‘To <strong>the</strong> Queen’,<br />

beginning ‘O loyal to <strong>the</strong> royal in thyself’.) <strong>The</strong>re followed, in April 1862, his first audience with Queen<br />

Victoria, at Osborne, Isle <strong>of</strong> Wight:<br />

I went down to see Tennyson who is very peculiar looking, tall, dark, with a fine head, long black flowing<br />

hair and a beard—oddly dressed, but <strong>the</strong>re is no affectation about him. I told him how much I admired his<br />

glorious lines to my precious Albert and how much comfort I found in his ‘In Memoriam’. He was full <strong>of</strong><br />

unbounded appreciation <strong>of</strong> beloved Albert. When he spoke <strong>of</strong> my own loss, <strong>of</strong> that to <strong>the</strong> Nation, his eyes<br />

quite filled with tears. (Queen Victoriaʹs journal, 14 April 1862, Dyson and Tennyson, 69)<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was humour, too, in <strong>the</strong>ir relation. ‘She was praising my poetry; I said “Every one writes verses now. I<br />

daresay Your Majesty does.” She smiled and said, “No! I never could bring two lines toge<strong>the</strong>r!”’ (Allingham,<br />

150, 18 Feb 1867). A later audience, in August 1883 when Tennyson was in his seventies, was movingly set<br />

down by <strong>the</strong> queen:<br />

After luncheon saw <strong>the</strong> great Poet Tennyson in dearest Albertʹs room for nearly an hour;—and most<br />

interesting it was. He is grown very old—his eyesight much impaired and he is very shaky on his legs. But<br />

he was very kind. Asked him to sit down … When I took leave <strong>of</strong> him, I thanked him for his kindness and<br />

said I needed it, for I had gone through so much—and he said you are so alone on that ‘terrible height, it is<br />

Terrible. Iʹve only a year or two to live but Iʹll be happy to do anything for you I can. Send for me whenever<br />

you like.’ I thanked him warmly. (Queen Victoriaʹs journal, 7 Aug 1883, Dyson and Tennyson, 102)<br />

‘Asked him to sit down’: for a sardonic rendering <strong>of</strong> such an audience, see Max Beerbohmʹs caricature, Mr.<br />

Tennyson reading ‘In Memoriam’ to his Sovereign (Beerbohm). <strong>The</strong>re, it is less <strong>the</strong> poetʹs vigorous left arm<br />

than his splayed legs that should establish his taking his liberty. But two royal pr<strong>of</strong>iles face his singular one.<br />

Maud (1855), and Idylls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> King (1859–1885)<br />

In July 1855 Tennyson published Maud, and O<strong>the</strong>r Poems. Notable among <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r poems was ‘<strong>The</strong> Charge<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Light Brigade’. <strong>The</strong> charge, at Balaklava in <strong>the</strong> Crimea, had taken place on 25 October. Tennysonʹs<br />

periodical publication in <strong>The</strong> Examiner (9 Dec 1854) had stirred not only <strong>the</strong> nation but <strong>the</strong> troops to whom<br />

copies were sent.<br />

‘This poem <strong>of</strong> Maud or <strong>the</strong> Madness is a little Hamlet, <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> a morbid, poetic soul, under <strong>the</strong><br />

blighting influence <strong>of</strong> a recklessly speculative age’; ‘<strong>The</strong> peculiarity <strong>of</strong> this poem is that different phases <strong>of</strong><br />

passion in one person take <strong>the</strong> place <strong>of</strong> different characters’ (Poems, 2.517–18).<br />

Tennysonʹs acquaintance with Dr Mat<strong>the</strong>w Allen, <strong>the</strong> wood‐carving financial speculator who was also a<br />

mad‐doctor (<strong>the</strong> poet John Clare was in his care for a while), was one experiential base for <strong>the</strong> poem—<br />

Tennyson visited his asylum near High Beech. What also courses through <strong>the</strong> poem is <strong>the</strong> black blood <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Tennysons. <strong>The</strong> poem aroused controversy, some <strong>of</strong> it low: ‘Sir, I used to worship you, but now I hate you. I<br />

loa<strong>the</strong> and detest you. You beast! So youʹve taken to imitating Longfellow. Yours in aversion’ (reported in<br />

letter <strong>of</strong> 8 Jan 1856, Letters <strong>of</strong> Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1.281–2). George Eliot reviewed it anonymously: ‘its<br />

tone is throughout morbid; it opens to us <strong>the</strong> self revelations <strong>of</strong> a morbid mind, and what it presents as <strong>the</strong><br />

cure for this mental disease is itself only a morbid conception <strong>of</strong> human relations’ (Westminster Review, Oct<br />

1855; G. Eliot, 192) . <strong>The</strong> poem was accused <strong>of</strong> craving war (<strong>the</strong> protagonist leaves at <strong>the</strong> end for <strong>the</strong> Crimea)<br />

and <strong>of</strong> fomenting sin. ‘If an author pipe <strong>of</strong> adultery, fornication, murder and suicide, set him down as <strong>the</strong><br />

practiser <strong>of</strong> those crimes’. Tennyson: ‘Adulterer I may be, fornicator I may be, murderer I may be, suicide I<br />

am not yet’ (Lincoln MS, draft ‘Materials for a Life <strong>of</strong> A. T.’; C. Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson, 286) . It<br />

remained one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poems that Tennyson was most moved to read aloud. Its sense <strong>of</strong> all that may impede<br />

marriage, or darken it, lived on in <strong>the</strong> two long narrative poems, <strong>of</strong> sombre power, that Tennyson published<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r in 1864: ‘Enoch Arden’ and ‘Aylmerʹs Field’.

Tennysonʹs Arthurian interests were lifelong: <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> early lyrical poems, ‘<strong>The</strong> Lady <strong>of</strong> Shalott’, ‘Sir<br />

Galahad’, and ‘Sir Launcelot and Queen Guinevere’, through <strong>the</strong> deeply contemplative ‘Morte dʹArthur’, to<br />

<strong>the</strong> elongated linking <strong>of</strong> narratives that became Idylls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> King. (A long I in Idylls; no article, not ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

Idylls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> King’; and an intimation that <strong>the</strong> series did not, though Hallam Tennyson uses <strong>the</strong> word,<br />

constitute an epic.)<br />

From his earliest years he had written out in prose various histories <strong>of</strong> Arthur … On Malory, on<br />

Layamonʹs Brut, on Lady Charlotte Guestʹs translation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mabinogion, on <strong>the</strong> old Chronicles, on old<br />

French Romance, on Celtic folklore, and largely on his own imagination, my fa<strong>the</strong>r founded his epic. (Poems,<br />

3.255)<br />

In 1848 Tennyson visited Ireland and Cornwall, taking up again his projected Arthurian enterprise. It was<br />

not until 1855 that he decided <strong>the</strong> shaping, and in 1859 <strong>the</strong> first four Idylls were published, Enid (later <strong>The</strong><br />

Marriage <strong>of</strong> Geraint and Geraint and Enid), Vivien (later Merlin and Vivien), Elaine (later Lancelot and<br />

Elaine), and Guinevere. A revision and expansion <strong>of</strong> Morte dʹArthur, as <strong>The</strong> Passing <strong>of</strong> Arthur, was<br />

published in 1869, with a note: ‘This last, <strong>the</strong> earliest written <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Poems, is here connected with <strong>the</strong> rest in<br />

accordance with an early project <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authorʹs’ (<strong>The</strong> Holy Grail and O<strong>the</strong>r Poems, ‘1870’). Gareth and<br />

Lynette was published in October 1872, and <strong>the</strong> Imperial Library edition <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs Works (1872–3) <strong>the</strong>n<br />

brought toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> series (with a new epilogue: ‘To <strong>the</strong> Queen’), virtually complete except for Balin and<br />

Balan (written 1874, published 1885).<br />

Victorian Arthurianism was sometimes moral, sometimes romantic, sometimes both. In <strong>The</strong> Return to<br />

Camelot: Chivalry and <strong>the</strong> English Gentleman, Mark Girouard noted that after <strong>the</strong> 1830s Tennysonʹs<br />

dealings with Arthurian material changed. ‘<strong>The</strong> 1850s were, indeed, studded with Arthurian projects’, and<br />

Tennyson more and more shaped inspiring models for ‘modern members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ruling class’ (Girouard, 180,<br />

184). But Tennyson had aspirations larger than <strong>the</strong> political, <strong>the</strong> passing. ‘As for <strong>the</strong> many meanings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

poem my fa<strong>the</strong>r would affirm “Poetry is like shot‐silk with many glancing colours”’. On his eightieth<br />

birthday, he said: ‘My meaning … was spiritual. I took <strong>the</strong> legendary stories <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Round Table as<br />

illustrations. I intended Arthur to represent <strong>the</strong> Ideal Soul <strong>of</strong> Man coming into contact with <strong>the</strong> warring<br />

elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flesh’ (Poems, 3.258–9).<br />

Deaths in <strong>the</strong> family, honours, and <strong>the</strong> peerage<br />

Tennysonʹs mo<strong>the</strong>r died in February 1865. <strong>The</strong>re is no recovering just what she meant to her son, though she<br />

is to be glimpsed, as a gracious silence, in <strong>the</strong> record <strong>of</strong> early life, her piety being praised in ‘Isabel’: ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

queen <strong>of</strong> marriage, a most perfect wife’. <strong>The</strong>n in April 1879 came <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> Charles, <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>r whom<br />

Tennyson loved best (‘altoge<strong>the</strong>r loveable, a second George Herbert in his utter faith’, Tennyson wrote to<br />

James Russell Lowell, on 18 November 1880; Letters, 3.199) , and whom he hauntingly commemorated in<br />

‘Frater Ave atque Vale’ and in ‘Prefatory Poem to My Bro<strong>the</strong>rʹs Sonnets’ (1879, opening Charlesʹs Collected<br />

Sonnets, 1880).<br />

But <strong>the</strong> immitigable grief was <strong>the</strong> grievous loss <strong>of</strong> Tennysonʹs son Lionel (b. 1854). In February 1878 Lionel<br />

had married Eleanor Locker. As is clear <strong>from</strong> a notebook <strong>of</strong> Lionelʹs, <strong>of</strong> 1874–6, in which he set down<br />

epigrams, observations, squibs, and light verse, he had a levity light‐years away <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> gravity <strong>of</strong> his elder<br />

bro<strong>the</strong>r, Hallam. Lionel made fretful his protective parents, with his dashing ways, his nattiness <strong>of</strong> garb, and<br />

his very unTennysonian stammer or stutter.<br />

Lionel Tennysonʹs work for <strong>the</strong> India Office took him to India in 1885, where he contracted fever, ‘hung<br />

between life and death for three months and a half’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.323), and <strong>the</strong>n, in April 1886,<br />

died in <strong>the</strong> Red Sea on his way home. Tennyson was desolate, but he strove to share his wifeʹs Christian<br />

fortitude—in her words, ‘<strong>The</strong> loss to us is indeed unspeakable but infinite Love and Wisdom have ordained<br />

it’ (26 Oct 1886, Letters, 3.343). Tennyson was to realize such family tragedy, both personal and everywhere,<br />

in one <strong>of</strong> his finest poems <strong>of</strong> saddened gratitude: ‘To <strong>the</strong> Marquis <strong>of</strong> Dufferin and Ava’. His love <strong>of</strong> Lionel

lived on in his love <strong>of</strong> his grandsons: first, Eleanorʹs and Lionelʹs Alfred B. S. Tennyson (b. 1878—see <strong>the</strong><br />

endearing playfulness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dedication to Ballads and O<strong>the</strong>r Poems, 1880, and ‘To Alfred Tennyson My<br />

Grandson’); and <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>ir Charles Tennyson (b. 1879) who lived to a great age, nearly 100, to honour his<br />

grandfa<strong>the</strong>r in works biographical and editorial.<br />

Honours came to Tennyson with and following <strong>the</strong> laureateship. In June 1855 he received an honorary DCL<br />

at Oxford; <strong>the</strong> occasion was graced by <strong>the</strong> affectionate impudence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cry (adapting <strong>the</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

May Queen’), ‘Did your mo<strong>the</strong>r call you early, dear?’ In 1869 he became an honorary fellow <strong>of</strong> Trinity<br />

College, Cambridge (where nei<strong>the</strong>r he in <strong>the</strong> past nor his son Hallam in <strong>the</strong> immediate future proceeded to a<br />

degree). In March 1880 he was invited to stand for <strong>the</strong> lord rectorship <strong>of</strong> Glasgow University, but withdrew<br />

when he learned that <strong>the</strong> election was conducted along party lines. He had in 1865 refused <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>of</strong> a<br />

baronetcy, and again in 1873, 1874, and 1880. <strong>The</strong>n in September 1883 he accepted a barony, acknowledging<br />

to <strong>the</strong> queen ‘This public mark <strong>of</strong> your Majestyʹs esteem which recognizes in my person <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong><br />