application/pdf : 241 Ko - Abeille Musique

application/pdf : 241 Ko - Abeille Musique

application/pdf : 241 Ko - Abeille Musique

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

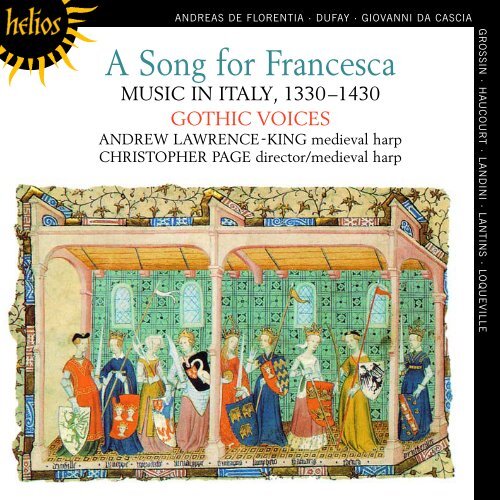

ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA . DUFAY . GIOVANNI DA CASCIA<br />

A Song for Francesca<br />

MUSIC IN ITALY, 1330–1430<br />

GOTHIC VOICES<br />

ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING medieval harp<br />

CHRISTOPHER PAGE director/medieval harp<br />

GROSSIN . HAUCOURT . LANDINI . LANTINS . LOQUEVILLE

I<br />

TALY POSSESSED a thriving and distinctive musical culture<br />

during the fourteenth century. By the early 1400s, however,<br />

Italian listeners had become deeply interested in the music<br />

of French and northern European composers. This recording<br />

explores the contrast between the two repertories—the native<br />

Italian and the borrowed French.<br />

Tracks 1 to 9 reveal the vigour and independence of<br />

the Italian tradition in the century of Petrarch and Boccaccio.<br />

Our title is taken from the monophonic ballata Amor mi fa<br />

cantar a la Francesca 6, meaning ‘Love makes me sing to<br />

Francesca’ but also ‘Love makes me sing in the French style’.<br />

This beguiling piece may represent the kind of music which the<br />

well born young men and women of Boccaccio’s Decameron<br />

sang and played in their Tuscan villas during the time of plague<br />

in 1348. It is preserved in the Vatican manuscript Rossi 215, a<br />

source which derives from the musical circle around Alberto<br />

della Scala in Padua during the 1330s and 1340s, and after<br />

1337 in Verona. This manuscript is also the earliest extant<br />

collection of Italian secular polyphony. Among its polyphonic<br />

items is Quando i oselli canta 3, a piece which shows<br />

important aspects of trecento polyphonic style in their pristine<br />

state. It is a madrígal, a distinctively Italian form (not to be<br />

confused with its Renaissance counterpart) which usually<br />

comprises two or three stanzas of three lines each (terzetti)<br />

followed by a ritornello. In conventional practice the music for<br />

each of the terzetti was identical, while the ritornello had its<br />

own music. All of these formal features are displayed by<br />

Quando i oselli canta and, like the great majority of trecento<br />

madrigals and ballate (but in sharp contrast to the greater part<br />

of the fourteenth-century French repertory), Quando i oselli<br />

canta is a two-part composition. The upper voice has a florid<br />

and mildly virtuosic character, while the lower one moves in<br />

longer note values, displaying a deliberate rhythmic plainness<br />

and a preference for stepwise motion. At times, the contrast<br />

between the two parts is very marked indeed, and we begin<br />

to understand why the Paduan theorist Antonio da Tempo<br />

(Trattato delle rime volgari, 1332) regarded ‘rustic sections’<br />

(partes rusticales) as a characteristic trait of the madrígal;<br />

there is undeniably something of the bagpipe in the pedal-point<br />

effect where the composer sets the words ‘La pasturele’ in the<br />

first terzetto of Quando i oselli canta. It is quite possible<br />

indeed that the two-part style of the trecento began as a form<br />

of improvized homophonic singing whose origins may well<br />

be popular and vocal / instrumental. The ritornello of Quando<br />

i oselli canta, for example, is little more than a series of<br />

parallel fifths with a few passing notes here and there and<br />

the occasional octave added to mark key structural points in<br />

the music.<br />

This two-part style, found in so much Italian music of the<br />

trecento, has often been described as one in which the lower<br />

voice ‘accompanies’ the upper, but in practice the artistic<br />

relationship of the parts is more complex. Once again Quando<br />

i oselli canta is a telling piece, for its lower part has the<br />

melodic form ABA (not counting the ritornello). The upper part<br />

does not share this melodic shape, however, and might<br />

therefore be described as a decoration of the ‘tune’ in the lower<br />

voice. Throughout the trecento repertory, indeed, there is a<br />

danger that we will direct our attention to the wrong part.<br />

Even in a florid piece like Quando la stella 5, a madrígal<br />

by Giovanni da Cascia (Johannes de Florentia), we should<br />

perhaps be focusing our attention upon the text as it is plainly<br />

and boldly declaimed by the melody in the lower part.<br />

To illustrate the later phases of northern Italian polyphony<br />

we have drawn upon the instrumental music of the Franco-<br />

Italian repertoire contained in the Faenza codex 4 and 7, and<br />

upon the ballate of two Florentine composers: the celebrated<br />

Francesco Landini 8 and 9 and his remarkable but littleknown<br />

colleague Andreas de Florentia 1 and 2. (Johannes<br />

Ciconia, whose music would readily find a place in the scheme<br />

of this disc, deserves a recording project to himself.) The items<br />

presented here are all polyphonic ballate in accordance with<br />

the growing importance of that genre from the 1360s onwards.<br />

As with most medieval forms of vernacular lyric poetry set to<br />

polyphonic music, the ballata is obedient to two fundamental<br />

2

principles of organization: first, the musical form is created<br />

by arranging two music units in a pattern of repetition and<br />

variation; and secondly, a section of text is never sung and<br />

then immediately repeated. The musical scheme of the ballata<br />

as it appears in the works recorded here may be represented<br />

as: A (ripresa)–bb (two piedi)–a (volta)–A (ripresa).<br />

Andreas de Florentia entered the order of the Servi di Maria<br />

in Florence in 1375 and was an organist like Landini. His<br />

ballata Per la ver’onestà 2 displays a mature two-voice style<br />

in which the parts are more homogeneous in character than in<br />

earlier pieces such as Quando la stella. Per la ver’onestà is a<br />

fluent dialogue in which the voices are united by passages of<br />

imitation and by the exchange of motifs. Something similar<br />

may be said for Landini’s Ochi dolenti mie 8 where scarcely<br />

a note is wasted.<br />

The selection of pieces (track bl onwards) from the Italian,<br />

and possibly Venetian, manuscript Canonici misc. 213 begins<br />

with a Latin motet to the Virgin, undoubtedly the work of a<br />

composer from northern Europe. Its five-part texture is quite<br />

exceptional for this date (probably the 1420s); only in the<br />

English Old Hall manuscript, or in the motets of Dufay, do we<br />

find other examples. It is isorhythmic in all five parts and<br />

remarkably consonant. Could this beautiful and anonymous<br />

piece be the work of the greatest composer of the period,<br />

Guillaume Dufay?<br />

All of the remaining compositions are cast in the dominant<br />

song-form of the fifteenth century, the rondeau. All but one of<br />

them are three-part pieces created by a cantus–tenor duet<br />

that is given extra harmonic colour and rhythmic impetus by<br />

a contratenor. The range of styles is considerable. Plaindre<br />

m’estuet bp by Hugo de Lantins (a setting of a poem with a<br />

shameless acrostic) has several extended passages of<br />

imitation, principally between the cantus and tenor, which can<br />

3<br />

be pointed in performance (as they are here) by appropriate<br />

texting; all three parts of the song are texted in the manuscript.<br />

The harmonic style is rich and sonorous with many full triads.<br />

The anonymous Confort d’amours br, a four-part piece,<br />

displays a rhythmic style often found in Canonici misc. 213;<br />

the mensuration corresponds to a modern and the<br />

rhythms in the upper parts alternate nervously between<br />

crotchet–quaver and quaver–crotchet patterns in such a way<br />

(and this is a key point of the style) that they rarely<br />

synchronize; insistent hemiola patterns (where the bar is<br />

filled by three crotchets) also vary the rhythm. As a result<br />

there is movement on virtually every beat of the measure<br />

throughout the piece and the impression is one of restless<br />

motion. Special points of interest in this piece (and we have<br />

been unable to find another one quite like it) are the wide<br />

compass (seventeen notes in all) and the composer’s mild<br />

experiments in chromaticism.<br />

All of the composers of these items were northerners.<br />

Richard Loqueville became master of the choristers at Cambrai<br />

Cathedral in 1413; he played the harp, and several of his<br />

chansons are performed here on a reproduction of the kind of<br />

instrument that he would have used. These gracious songs,<br />

whose economy of means makes such a striking contrast with<br />

the earlier Italian pieces, are perfectly idiomatic for the sound<br />

and articulation of the harp. Of Hugo de Lantins little is known<br />

except that he flourished from around 1420 to 1430 and may,<br />

like Loqueville, have had connections with Guillaume Dufay.<br />

And of Dufay, the flower of all musicians in his century, what<br />

can be said that has not been said already? His Quel fronte<br />

signorille in paradiso bm is a perfect example of Italian sweetness<br />

a la Francesca.<br />

CHRISTOPHER PAGE © 1988

ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA (died c1415)<br />

1 Astio non morì mai. Spite is not dead.<br />

Nel foco sempre ardendo He is consumed in the ever-burning fire,<br />

Consùmasi stridendo screaming<br />

Con dolore e con guai. with pain and woe.<br />

Le bilance al cul porta; He carries the scales behind him;<br />

Per tener ragion torta so that justice is perverted<br />

Attuta gente mai. for everyone.<br />

Ignudo in cuffia e in braca. Naked, but for cap and breaches,<br />

Sotto la rota vaca he sprawls beneath the wheel [of fortune],<br />

Sança levarsi mai. never to rise again.<br />

Astio non morì mai. Spite is not dead.<br />

ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA (died c1415)<br />

2 Per la ver’onestà che teco regna, Because of the true modesty which dwells in you,<br />

Donna gentile e bella, noble and beautiful lady,<br />

Io a mme stesso vieto la favella. I forbid myself to speak.<br />

Ma pur la greve pena, che nascosa Yet the great grief<br />

O dentr’al cor lungo tempo tenuta, which I have concealed in my heart for so long<br />

Mostra segno di fuor che brama posa, openly shows that it longs for relief,<br />

Sperando che de tte sie conceduta. hoping that you will grant it.<br />

Adunque, s’i’ mi vivo a lingua muta, Therefore, though my tongue remains silent,<br />

Qualche modo m’insegna my grief somehow teaches me<br />

Chi’ i’ facci l’alma di piacerti degna. to make my soul worthy to please you.<br />

ANONYMOUS<br />

3 Quando i oselli canta When the birds sing<br />

La pasturele vano a la campagna, the shepherdesses go into the country,<br />

Quando i oselli canta. when the birds sing.<br />

Fan girlande de erba, They make garlands of herbs,<br />

Frescheta verde, et altre belle fiore, fresh and green, and pretty flowers too,<br />

Fan girlande de erba. they make garlands of herbs.<br />

Quest’ è quel dolce tempo It was in this sweet season<br />

Ch’amor mi prese d’una pasturella, that I fell in love with a certain shepherdess,<br />

Quest’ è quel dolce tempo. it was in this sweet season.<br />

Basar la volsi a dème de la roca. I turned to kiss her and she me with her distaff.<br />

4

GIOVANNI DA CASCIA (JOHANNES DE FLORENTIA, fl1340–1350)<br />

5 Quando la stella press’ a l’alba spira At dawn, when the stars are extinguished<br />

E ’l sol si mostra inverso l’oriente, and the sun shows itself in the east,<br />

Amor gentil m’aparse nella mente. noble Love came to me in a vision.<br />

La vaga donna col benigno aspetto He held in his arms with delight<br />

Tenea nelle bracca per diletto; a fair lady with the kind looks;<br />

Poi la coperse di perfetta luce then Love clothed her with perfect light<br />

E dul suo draggio il fece vestita, and dressed her in his rays,<br />

Vermiglio e bianco di color partita. mixed of red and white.<br />

Una ghirlanda ’n su le trecce bionde He placed on her blonde tresses<br />

Di foglie verdi pose con le fronde. a garland of fresh leaves and greenery.<br />

ANONYMOUS<br />

6 Amor mi fa cantar a la Francesca. Love makes me sing in the French manner.<br />

Perchè questo m’aven non olso dire, The reason for this I dare not tell,<br />

Chè quella donna che me fa languire for I fear that the lady for whom I languish<br />

Temo che non verebe a la mia tresca. would not join my dance.<br />

A lei sum fermo celar el mio core I am resolved to conceal my feelings<br />

E consumarmi inançi per so amore, and waste away for love of her,<br />

Ch’ almen moro per cosa gentilesca. for at least I die in a noble cause.<br />

Done, di vero dir ve posso tanto Ladies, this much I can truthfully tell you<br />

Che questa donna, per cui piango a canto, that this lady for whom I grieve and sing,<br />

E come rosa in spin morbida e fresca. is delicate and fresh like a rose among thorns.<br />

Amor mi fa cantar a la Francesca. Love makes me sing in the French manner.<br />

FRANCESCO LANDINI (c1325–1397)<br />

8 Ochi dolenti mie, che pur piangete, My grieving eyes, ever weeping,<br />

Po che vedete, since you see<br />

Che sol per honestà non vi contento. that for modesty’s sake I will not satisfy you.<br />

Non a diviso la mente ’l disio My mind desires exactly the same<br />

Con voi che tante lagrime versate, as you, who weep so many tears,<br />

Perche da voi si cela el viso pio, because that lovely face, which has deprived me<br />

Il qual privato m’a de libertate. of my liberty, is concealed from you.<br />

Gran virtù é rafrenar volontate It is most valorous to curb one’s desire<br />

Per honestate, for the sake of modesty,<br />

Che seguir donna è sofferir tormento. for to court a lady is to suffer torment.<br />

5

FRANCESCO LANDINI (c1325–1397)<br />

9 Per seguir la sperança che m’ancide, To pursue the hope which kills me,<br />

Donna, vo cercand’io lady, I seek<br />

Di celato tener el mie disio. to keep my desire concealed.<br />

Ne vogliate, cagion di tanta pena, You who are the cause of so much grief, do not try<br />

El mie grieve tormento discovrire. to reveal my great torment.<br />

Pero che la ragion pur mi raffrena, For reason still holds me back,<br />

Dond’io disposto son così morire. and so I am ready to die.<br />

Ma ben ti priego, amor, de! non soffrire, But I beg you, Love, not to let<br />

Ch’i’ pera in tale oblio, me perish in such oblivion:<br />

Falle palese, tu, il voler mio. you yourself reveal to her my desire.<br />

ANONYMOUS<br />

bl O regina seculi, O queen of the world,<br />

Salvatrix sempiterna, eternal source of salvation,<br />

O divine fidei O divine strengthener<br />

Firmatrix, nos adjuva; of faith, help us;<br />

Ora pro nobis, pia, beseech your son for us,<br />

Jesum tuum filium, gentle Mary,<br />

Ut nobis auxilium that he may help us,<br />

Conferat, dulcis Maria. O sweet Mary.<br />

Amen. Amen.<br />

Reparatrix Maria, O Mary who restores all,<br />

Nobilis virgo pura, noble and pure virgin,<br />

[Con]solatrix anime, she who calms the soul,<br />

De procella ventura, O star of the sea,<br />

Famulos [tuos], pia, guard your dependents, gentle Mary,<br />

[Defende], maris stella; from the storm which is to come;<br />

Deprecare filium beseech your son<br />

Ut donet transmeare that he may grant us a safe passage<br />

Seculi periculum through the perils of this world<br />

Ut videamus eum so that we may look upon him<br />

In poli aula. in the hall of heaven.<br />

Amen. Amen.<br />

6

GUILLAUME DUFAY (1397–1474)<br />

bm Quel fronte signorille in paradiso That noble brow<br />

Scorge l’anima mia, shows my soul the way to Paradise,<br />

Mentre che in sua balia while she holds me fast in her power,<br />

Streto mi tiene mirando il suo bel viso. beholding her fair face.<br />

I ochi trapassa tutti dei altri el viso Her face transfixes the eyes of all who look upon it<br />

Con sì dolce armonia, with such sweet harmony,<br />

Che i cor nostri s’en via that our hearts are stolen away<br />

Pian pian in suso vanno in paradiso. and gently ascend to Paradise.<br />

HUGO DE LANTINS (fl 1420–1430)<br />

bp Plaindre m’estuet de ma damme jolye I must complain of my fair lady<br />

V ers tous amans, qui par sa courtoisie to all lovers, for she has had the courtesy<br />

T out m’a failly sa foy qu’avoit promis; to break completely the promise which she made me;<br />

A ultre de moy, taut que seroye vis, all her life, while I am still alive,<br />

J amais changier ne devoit en sa vie. she ought never to change me for another.<br />

Ne scay comment elle a fait departie I do not know how she came to leave me;<br />

De moy; certes, ne le cuidesse mye I certainly never expected<br />

E n tel deffault trouver, ce m’estoit vis. to see her so transgress, or so I thought.<br />

Plaindre m’estuet … I must complain …<br />

Mais je scay bien que la merancolie But I am sure this folly of hers<br />

E n moy n’ara pour yceste folye; will never make me melancholy;<br />

Renouveler voldray malgre son vis, I will begin again, in spite of her,<br />

D’aultre damme dont mon cuer est souspris, with another lady of whom I am enamoured,<br />

E t renuncer de tout sa campaignye. and renounce her company altogether.<br />

Plaindre m’estuet … I must complain …<br />

JOHANNES HAUCOURT (fl 1390–after 1416)<br />

bq Je demande ma bienvenue: I ask my sweetheart:<br />

‘Il a longtemps que ne vous vi; ‘I have not seen you for a long time;<br />

Dites, sui je plus vostre ami; tell me, am I still your love;<br />

Avés bien vostre foy tenue? have you kept faith with me?<br />

La meilleur desoubs la nue You are the most faithful woman on earth,<br />

Estes se l’avés fait ensi.’ if you have.’<br />

Je demande … I ask …<br />

Je vous ai moult longtemps perdue, I have been parted from you for a very long time,<br />

Dont j’ay esté en grant soussi, which has made me very unhappy,<br />

Mais de tous mes maulx sui gari, but I am cured of all my ills,<br />

Puis qu’en bon point je vous ay veue.’ now that I have found you well.’<br />

Je demande … I ask …<br />

7

ANONYMOUS<br />

br Confort d’amours humblement The consolation of love I humbly<br />

Vous requier, ma doulce dame, beg of you, sweet lady,<br />

Car en vous est, sans nul blasme, for in you, without any dishonourable intention,<br />

Mon espoir entirement. all my hope resides.<br />

Pour oster le grief tourment To relieve the grievous torment<br />

Qui mon povre cuer entame, which afflicts my poor heart,<br />

Confort d’amours … The consolation …<br />

Considerés doulcement Look with compassion<br />

L’ardant desir qui m’enflamme, on the burning desire which consumes me,<br />

Affin que de corps et d’ame so that with body and soul<br />

Vous serve songneusement. I may dutifully serve you.<br />

Confort d’amours … The consolation …<br />

ESTIENNE GROSSIN (fl1418–1421)<br />

btVa t’ent souspir, je t’en supplie, Go forth, sigh, I beg you,<br />

Vers ma dame hastivement, hurry to my lady,<br />

Et de par moy tres doulchement and on my behalf very gently<br />

Fay li savoir ma maladie. inform her of my affliction.<br />

Di lui que je n’ay nulle envie Tell her that I have no wish<br />

D’aultre choisir certainement: to choose another by any means:<br />

Va t’ent souspir … Go forth, sigh …<br />

Je me souhaide une nuitie I wish for nothing more<br />

Aveuc elle tan seulement; than to spend one night with her;<br />

Si me donroit aligement that would cure me<br />

De tons ma maulx, je le t’affye! of all my ills, I assure you!<br />

Va t’ent souspir … Go forth, sigh …<br />

If you have enjoyed this recording perhaps you would like a catalogue listing the many others available on the Hyperion and Helios labels. If so, please<br />

write to Hyperion Records Ltd, PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, England, or email us at info@hyperion-records.co.uk, and we will be pleased to post you<br />

one free of charge.<br />

The Hyperion catalogue can also be accessed on the Internet at www.hyperion-records.co.uk<br />

8

SOME OTHER GOTHIC VOICES RECORDINGS<br />

LANCASTER AND VALOIS<br />

French and English Music, c1350–1420<br />

Compact Disc CDH55294<br />

‘We are exceptionally lucky to have such brilliantly persuasive<br />

advocates of such wonderful music’ (Gramophone)<br />

GRAMOPHONE CRITICS’ CHOICE<br />

MUSIC FOR THE LION-HEARTED KING<br />

Compact Disc CDH55292<br />

‘This is rather special—the best record I have ever reviewed’<br />

(Gramophone) GRAMOPHONE CRITICS’ CHOICE<br />

THE CASTLE OF FAIR WELCOME<br />

Courtly songs of the later fifteenth century<br />

Compact Disc CDH55274<br />

‘The sound is beautifully carved out, and the ensemble includes some<br />

of Britain’s finest singers’ (Gramophone)<br />

PIERRE DE LA RUE (c1452–1518)<br />

Missa De Feria & Missa Sancta Dei genitrix<br />

Compact Disc CDH55296<br />

‘A revelation, not only of top-rate neglected music, but also how it<br />

should sound. A perfect marriage of musical style and scholarship.<br />

Insight and enjoyment hand in hand’ (Classic CD)<br />

‘Gothic Voices have once again opened a window on a forgotten world’<br />

(BBC Music Magazine)<br />

9

Chanson pour Francesca MUSIQUE EN ITALIE, 1330–1430<br />

E<br />

N ITALIE, le XIV e siècle fut marqué par une culture<br />

musicale florissante et singulière. Pourtant, au début des<br />

années 1400, les auditeurs italiens étaient devenus férus<br />

des compositeurs français et nord-européens. Cet enregistrement<br />

explore le contraste entre ces deux répertoires : l’italien<br />

autochtone et le français d’emprunt.<br />

Les pistes 1 à 9 révèlent la vigueur et l’indépendance<br />

de la tradition italienne au siècle de Pétrarque et de Boccace.<br />

Notre titre vient de la ballata monophonique Amor mi fa cantar<br />

a la Francesca 6, ce qui signifie à la fois « L’amour me<br />

fait chanter à Francesca » et « L’amour me fait chanter à la<br />

française ». Cette pièce charmante pourrait incarner le genre<br />

de musique que la jeunesse bien née du Décaméron de<br />

Boccace chantait et jouait dans les villas toscanes pendant la<br />

peste de 1348. Elle est conservée dans le manuscrit Rossi 215<br />

du Vatican, qui provient du cercle musical constitué autour<br />

d’Alberto della Scala, à Padoue (dans les années 1330 et<br />

1340) et à Vérone (après 1337). Ce manuscrit, qui se trouve<br />

être le plus ancien recueil de polyphonie profane italienne,<br />

recèle notamment Quando i oselli canta 3, une œuvre qui<br />

montre, dans leur état premier, d’importants aspects du style<br />

polyphonique du trecento. Il s’agit d’un madrígal, une forme<br />

typiquement italienne (à ne pas confondre avec son équivalent<br />

de la Renaissance) qui compte généralement deux ou trois<br />

stances de trois vers chacune (terzetti), suivies d’un ritornello.<br />

Dans la pratique conventionnelle, tous les terzetti avaient la<br />

même musique, le ritornello ayant la sienne propre. Toutes ces<br />

caractéristiques formelles figurent dans Quando i oselli canta<br />

qui, comme la plupart des madrigaux et ballate du trecento<br />

(mais en contraste absolu avec l’essentiel du répertoire<br />

français du XIV e siècle), est une composition à deux parties. La<br />

voix supérieure présente un caractère fleuri et quelque peu<br />

virtuose ; l’inférieure, elle, se meut en valeurs de notes plus<br />

longues, affichant une simplicité rythmique délibérée et une<br />

prédilection pour le mouvement par degrés conjoints. Parfois,<br />

le contraste entre ces deux parties est très marqué, et l’on<br />

comprend un peu mieux pourqoui le théoricien padouan<br />

Antonio da Tempo (Trattato delle rime volgari, 1332)<br />

considérait les sections rustiques (partes rusticales) comme<br />

un trait caractéristique du madrígal ; il y a un indéniable<br />

quelque chose de la cornemuse dans l’effet de pédale, là où le<br />

compositeur met en musique « La pasturele », dans le premier<br />

terzetto de Quando i oselli canta. Car il est fort possible que<br />

le style à deux parties du trecento ait d’abord pris la forme<br />

d’un chant homophonique improvisé, dont les origines<br />

pourraient bien être et populaires et vocales / instrumentales.<br />

Le ritornello de Quando i oselli canta, par exemple, n’est guère<br />

plus qu’une série de quintes parallèles avec, ça et là, quelques<br />

notes de passage et de sporadiques octaves pour marquer les<br />

points structurels clé de la musique.<br />

Ce style à deux parties, présent dans tant de pièces<br />

italiennes du trecento, a souvent été décrit comme un style<br />

dans lequel la voix inférieure « accompagne » la supérieure<br />

mais, dans les faits, la relation artistique des deux parties est<br />

plus complexe. Là encore, Quando i oselli canta est une œuvre<br />

parlante, car sa partie inférieure affecte la forme mélodique<br />

ABA (en ne comptant pas le ritornello). Cette forme n’est<br />

cependant pas celle de la partie supérieure, qui pourrait donc<br />

être perçue comme une décoration de la « mélodie » à la voix<br />

inférieure. Avec tout le répertoire du trecento, nous courons le<br />

risque de nous polariser sur la mauvaise partie. Même une<br />

pièce ornée comme Quando la stella 5, un madrígal de<br />

Giovanni da Cascia (Johannes de Florentia), requerrait peutêtre<br />

que nous nous focalisions sur le texte, distinctement et<br />

fermement déclamé par la mélodie à la partie inférieure.<br />

Notre illustration des dernières phases de la polyphonie<br />

de l’Italie du Nord repose sur la musique instrumentale du<br />

répertoire franco-italien contenu dans le codex de Faenza 4 et<br />

7, ainsi que sur les ballate de deux compositeurs florentins :<br />

le célèbre Francisco Landini 8 et 9, et son remarquable,<br />

mais méconnu, collègue Andreas de Florentia 1 et 2.<br />

(Johannes Ciconia, dont la musique trouverait volontiers sa<br />

10

place sur ce disque, mérite un enregistrement à lui seul.) Les<br />

pièces proposées ici sont toutes des ballate polyphoniques,<br />

genre qui prit une importance croissante à partir des années<br />

1360. Comme la plupart des formes médiévales de poésie<br />

lyrique vernaculaire mises en polyphonie, la ballata obéit<br />

à deux grands principes d’organisation : primo, la forme<br />

musicale est créée en arrangeant deux unités musicales selon<br />

un schéma de répétition et de variation ; secundo, jamais une<br />

section textuelle n’est reprise juste après avoir été chantée.<br />

Comme l’attestent les œuvres enregistrées ici, le schéma de<br />

la ballata peut être présenté ainsi : A (ripresa)–bb (deux<br />

piedi)–a (volta)–A (ripresa).<br />

Entré dans l’ordre des Servi di Maria à Florence en 1375,<br />

Andreas de Florentia fut organiste, comme Landini. Sa ballata<br />

Per la ver’onestà 2 affiche un style à deux voix abouti, où les<br />

parties ont un caractère davantage homogène que dans des<br />

pièces antérieures comme Quando la stella. Per la ver’onestà<br />

est un dialogue fluide où les voix sont unies par des passages<br />

imitatifs et par l’échange de motifs. Il en va un peu de même<br />

pour Ochi dolenti mie 8 de Landini, où presque aucune note<br />

n’est gâchée.<br />

La sélection de pièces (à partir de bl) issues du manuscrit<br />

italien (probablement vénitien) Canonici misc. 213 s’ouvre sur<br />

un motet latin à la Vierge—indubitablement l’œuvre d’un<br />

compositeur d’Europe du Nord. Sa texture à cinq parties, tout<br />

à fait exceptionnelle pour l’époque (probablement les années<br />

1420), ne se retrouve que dans le manuscrit anglais d’Old<br />

Hall ou dans les motets de Dufay. Il est isorythmique dans<br />

l’ensemble des cinq parties et remarquablement consonant.<br />

Cette superbe pièce anonyme pourrait-elle être l’œuvre du<br />

plus grand compositeur de l’époque, Guillaume Dufay ?<br />

Toutes les autres compositions sont coulées dans la forme<br />

qui domina la chanson du XV e siècle : le rondeau. Toutes, sauf<br />

une, sont des pièces à trois parties où un contratenor vient<br />

conférer à un duo cantus/ténor un surcroît de couleur<br />

harmonique et d’élan rythmique. L’éventail stylistique est<br />

considérable. Plaindre m’estuet bp de Hugo de Lantins (mise<br />

11<br />

en musique d’un poème à l’acrostiche éhonté) comporte<br />

plusieurs longs passages imitatifs, surtout entre le cantus et le<br />

ténor, que l’on peut signifier lors de l’interprétation (comme ici)<br />

par un texte approprié ; les trois parties de la chanson sont<br />

toutes cum littera dans le manuscrit. Le style harmonique,<br />

gorgé de triades complètes, est riche et sonore. Confort<br />

d’amours br, une pièce anonyme à quatre parties, présente<br />

un style rythmique courant dans le misc. Canonici 213 ;<br />

la mensuration équivaut à un moderne et les rythmes<br />

des parties supérieures alternent nerveusement entre noire–<br />

croche et croche–noire, en sorte que (et c’est un point clé de<br />

ce style) ils se synchronisent rarement ; d’insistants modèles<br />

d’hémiole (où la mesure à est comblée par trois noires)<br />

varient également le rythme. Il en résulte, tout au long de la<br />

pièce, un mouvement sur presque chaque temps de la mesure<br />

à et donc une impression de mouvement incessant. Cette<br />

pièce vaut tout particulièrement (et nous ne sommes pas<br />

parvenus à trouver son exact équivalent) pour son large<br />

ambitus (dix-sept notes en tout) et pour les légères<br />

expérimentations chromatiques du compositeur.<br />

Tous les compositeurs de ces pièces étaient des gens<br />

du Nord. Richard Loqueville devint maître des choristes à<br />

la cathédrale de Cambrai en 1413 ; il jouait de la harpe,<br />

et plusieurs de ses chansons sont exécutées ici sur la<br />

reproduction d’un instrument qu’il aurait pu utiliser. Ces<br />

chansons gracieuses, dont l’économie de moyens contraste<br />

étonnamment avec les pièces italiennes antérieures, conviennent<br />

parfaitement à la sonorité et à l’articulation de la<br />

harpe. On sait peu de choses sur Hugo de Lantins, hormis qu’il<br />

prospéra de 1420 environ à 1430 et que, comme Loqueville, il<br />

a pu avoir des liens avec Guillaume Dufay. Et de Dufay, la fleur<br />

de tous les musiciens de son siècle, que dire qui n’ait déjà<br />

été dit ? Son Quel fronte signorille in paradiso bm illustre à<br />

merveille la douceur italienne a la Francesca.<br />

CHRISTOPHER PAGE © 1988<br />

Traduction HYPERION, 2006

Ein Lied für Francesca MUSIK IN ITALIEN, 1330–1430<br />

I<br />

TALIEN VERFÜGTE IM 14. JAHRHUNDERT über eine blühende<br />

und einzigartige Musikkultur. Zu Beginn des 15. Jahr-<br />

hunderts begannen sich die italienischen Hörer allerdings<br />

stark für die Musik französischer und nordeuropäischer<br />

<strong>Ko</strong>mponisten zu interessieren. Die hier vorliegende Aufnahme<br />

spürt dem Unterschied zwischen den beiden Repertoires nach:<br />

dem einheimisch italienischen und dem übernommenen<br />

französischen.<br />

Die Spuren 1 bis 9 bezeugen die Lebendigkeit und<br />

Eigenständigkeit der italienischen Tradition im Jahrhundert des<br />

Petrarchs und Boccaccios. Unser Titel stammt aus der monophonen<br />

Ballade Amor mi fa cantar a la Francesca 6, was<br />

soviel bedeutet wie „Durch Liebe singe ich für Francesca“,<br />

aber eben auch „Durch Liebe singe ich im französischen Stil“.<br />

Dieses betörende Stück gehörte womöglich zu den Stücken, die<br />

die jungen Männer und Frauen aus gutem Haus in Boccaccios<br />

Decameron in ihren toskanischen Villen sangen und spielten,<br />

während 1348 die Plage hausierte. Das Musikstück ist im<br />

vatikanischen Manuskript Rossi 215 enthalten, eine Quelle, die<br />

ihren Ursprung im musikalischen Kreis um Alberto della Scala<br />

in Padua in den 1330er und 1340er Jahren sowie nach 1337<br />

in Verona hat. Dieses Manuskript ist auch die früheste uns<br />

erhaltene substantielle Sammlung italienischer weltlicher<br />

Polyphonie. Unter ihren polyphonen Stücken offenbart Quando<br />

i oselli canta 3 wichtige Aspekte des polyphonen Trecento-<br />

Stils in seiner reinen Ausprägung. Man hat es hier mit einem<br />

Madrigal zu tun, eine spezielle italienische Gattung (die nicht<br />

mit seiner Renaissanceform verwechselt werden darf), die<br />

gewöhnlich aus zwei oder drei Strophen mit jeweils drei<br />

Zeilen (terzetti) und darauf folgendem Ritornell besteht.<br />

Normalerweise war die Musik für jedes Terzett identisch,<br />

während das Ritornell seine eigene Musik hatte. All diese<br />

formalen Eigenschaften kann man im Quando i oselli<br />

canta wiedererkennen. Dieses Stück ist wie der Großteil<br />

der Trecentomadrigale und -balladen (aber im deutlichen<br />

Gegensatz zu der Mehrheit des französischen Repertoires aus<br />

dem 14. Jahrhundert) eine zweistimmige <strong>Ko</strong>mposition. Die<br />

Oberstimme zeichnet sich durch einen verzierenden und mäßig<br />

virtuosen Charakter aus, während sich die Unterstimme in<br />

längeren Notenwerten fortbewegt und dabei eine bewusste<br />

rhythmische Einfachheit sowie eine Neigung zur melodischen<br />

Fortschreitung in kleinen Schritten erkennen lässt. Manchmal<br />

ist der <strong>Ko</strong>ntrast zwischen den zwei Stimmen tatsächlich sehr<br />

markant, und man versteht allmählich, warum der Theoriker<br />

aus Padua, Antonio da Tempo (Trattato delle rime volgari,<br />

1332), „rustikale Abschnitte“ (partes rusticales) als ein<br />

charakteristisches Merkmal des Madrigals anführte. Es gibt<br />

zweifellos an der Stelle, wo der <strong>Ko</strong>mponist im ersten Terzett<br />

des Quando i oselli canta die Worte „La pasturele“ vertonte,<br />

einen Dudelsackeffekt im Orgelpunkt. Es ist tatsächlich sehr<br />

wohl möglich, dass der zweistimmige Stil des Trecentos als<br />

eine Art improvisierter homophoner Gesang begann, dessen<br />

Wurzeln in Volks- und vokaler/instrumentaler Hofmusik liegen.<br />

Das Ritornell des Quando i oselli canta ist zum Beispiel nicht<br />

viel mehr als eine Reihe paralleler Quinten mit ein paar<br />

Durchgangsnoten hier und da und gelegentlich hinzugefügten<br />

Oktaven, um Schlüsselstellen in der Musik hervorzuheben.<br />

Über diesen so häufig in der italienischen Musik des<br />

Trecentos vorkommenden zweistimmigen Stil sagt man oft, die<br />

untere Stimme würde die Oberstimme „begleiten“. Aber in<br />

Wirklichkeit erweist sich die künstlerische Beziehung zwischen<br />

den Stimmen als komplexer. Wiederum ist Quando i oselli<br />

canta ein gutes Beispiel, da die Melodie der unteren Stimme<br />

die Form ABA vorweist (ohne dabei das Ritornell mitzurechnen).<br />

Die Oberstimme hat allerdings nicht dieselbe melodische<br />

Gestalt und könnte deshalb als Verzierung der in der tieferen<br />

Stimme gesungenen „Melodie“ beschrieben werden. Im<br />

gesamten Trecentorepertoire besteht wirklich die Gefahr, dass<br />

man seine Aufmerksamkeit der falschen Stimme schenkt.<br />

Selbst in solch einem stark verzierten Stück wie Quando la<br />

stella 5, einem Madrigal von Giovanni da Cascia (Johannes<br />

de Florentia), sollte man vielleicht seine Aufmerksamkeit<br />

12

dem Text schenken, der deutlich und klar vernehmlich in der Manuskript Canonici misc. 213 beginnt mit einer lateinischen<br />

Melodie der unteren Stimme artikuliert wird.<br />

Mottete über die Heilige Jungfrau, zweifellos das Werk eines<br />

Um die späteren Phasen norditalienischer Polyphonie zu <strong>Ko</strong>mponisten aus Nordeuropa. Ihr fünfstimmiger Satz ist<br />

illustrieren, muss man sich an die Instrumentalmusik des ziemlich ungewöhnlich für die Zeit (wahrscheinlich aus den<br />

fränkisch-italienischen Repertoires aus dem <strong>Ko</strong>dex Faenza<br />

wenden 4 und 7 sowie an die Balladen von zwei<br />

1420er Jahren). Nur im Old Hall-Manuskript oder in den<br />

Motetten von Dufay findet man andere Beispiele dieser Art.<br />

florentinischen <strong>Ko</strong>mponisten: dem berühmten Francesco<br />

Landini 8 und 9 und seinem bemerkenswerten, wenn auch<br />

wenig bekannten <strong>Ko</strong>llegen Andreas de Florentia 1 und 2.<br />

Unsere Motette ist in allen fünf Stimmen isorhythmisch und<br />

klingt erstaunlich konsonant. Könnte es sein, dass dieses<br />

wunderschöne und anonyme Stück das Werk des größten<br />

(Johannes Ciconia, dessen Musik leicht einen Platz im <strong>Ko</strong>mponisten jener Zeit, nämlich von Guillaume Dufay,<br />

Programm dieser CD finden würde, verdient sein eigenes stammt?<br />

Aufnahmeprojekt.) Der wachsenden Bedeutung des Ballad- Alle übrigen <strong>Ko</strong>mpositionen stehen in der im 15. Jahrengenres<br />

seit den 1360er Jahren Rechnung tragend sind alle hundert vorherrschenden Liedform, dem Rondeau. Alle außer<br />

hier vorgestellten Stücke polyphone Balladen. Wie bei den einer sind dreistimmige Stücke, deren <strong>Ko</strong>mposition mit einem<br />

meisten mittelalterlichen Gattungen, in denen die lyrische Cantus-Tenor-Duett begann, das dann durch einen <strong>Ko</strong>ntratenor<br />

Dichtung in der eigenen Sprache polyphon vertont wurde, zusätzliche harmonische Färbung und rhythmische Impulse<br />

gehorcht auch die Ballade zwei organisatorischen Grundprinzipien:<br />

Zum einen wird die musikalische Form durch die<br />

erhielt. Die Stilpalette ist erstaunlich breit. Plaindre m’estuet<br />

bp von Hugo de Lantins (eine Vertonung eines Gedichts mit<br />

Zusammenstellung von zwei musikalischen Einheiten in Form schamlosen Akrostichon) enthält diverse lange Passagen mit<br />

von Wiederholung und Variation gebildet, und zum anderen Imitationen hauptsächlich zwischen dem Cantus und Tenor.<br />

wird ein Textabschnitt niemals gesungen und dann sofort Diese Imitationen können bei einer Aufführung durch geeignete<br />

wiederholt. Das musikalische Schema der Ballade, wie es in Textunterlegung zugespitzt werden (wie das auch hier<br />

den auf dieser CD aufgenommenen Werken ersichtlich wird, geschieht). Allen drei Stimmen des Liedes wurden im Manu-<br />

kann wie folgt dargestellt werden: A (ripresa)–bb (zwei skript Text unterlegt. Die Harmonien klingen satt und klangvoll<br />

piedi)–a (volta)–A (ripresa).<br />

Andreas de Florentia trat 1375 in Florenz dem Orden<br />

und enthalten viele volle Dreiklänge. Das anonyme, vierstimmige<br />

Stück Confort d’amours br lässt eine Rhythmik<br />

der Diener Mariens bei und war wie Landini Organist.<br />

Seine Ballade Per la ver’onestà 2 zeigt einen reifen<br />

zweistimmigen Stil, in dem die Stimmen im Charakter homo-<br />

erkennen, der man häufig in der Manuskriptsammlung<br />

Canonici misc. 213 begegnet. Die Mensur entspricht einem<br />

modernen<br />

gener sind, als das in früheren Stücken wie Quando la stella<br />

der Fall war. Per la ver’onestà ist ein fließender Dialog, in dem<br />

die Stimmen durch Passagen mit imitierendem <strong>Ko</strong>ntrapunkt<br />

und Motivaustausch vereint werden. Ähnliches kann man auch<br />

über Landinis Ochi dolenti mie 8 sagen, wo kaum eine<br />

einzige Note überflüssig ist.<br />

Die Auswahl von Stücken (angefangen mit Band bl)<br />

aus dem italienischen und möglicherweise venezianischen<br />

-Takt, und die Rhythmen in den oberen Stimmen<br />

alternieren nervös zwischen Viertel-Achtel- und Achtel-Viertel-<br />

Gruppen, so dass die Stimmen kaum jemals synchron laufen<br />

(was ein Kennzeichen dieses Stils ist). Auch die unablässigen<br />

Hemiolengesten (wo der -Takt in drei Viertel unterteilt ist)<br />

variieren den Rhythmus. Demzufolge gibt es im gesamten<br />

Stück eine Bewegung auf fast jedem Schlag des -Takts und<br />

es entsteht ein ruheloser Eindruck. Interessante Aspekte<br />

in diesem Stück (und es gelang uns nicht, ein weiteres<br />

13

ebenbürtiges zu finden) sind der weite Tonumfang (insgesamt<br />

17 Noten) und die vorsichtigen Experimente des <strong>Ko</strong>mponisten<br />

mit Chromatik.<br />

Alle <strong>Ko</strong>mponisten dieser Stücke stammen aus dem Norden.<br />

Richard Loqueville wurde 1413 zum Magister puerorum an der<br />

Kathedrale in Cambrai ernannt. Er spielte die Harfe, und einige<br />

seiner Chansons wurden hier auf einem nachgebauten<br />

Instrument von der Art aufgenommen, die er selbst gespielt<br />

haben mag. Diese angenehmen Lieder, deren Ökonomie der<br />

Mittel im deutlichen Gegensatz zu den früheren italienischen<br />

14<br />

Stücken steht, sind für die Klang- und Artikulationsmöglichkeiten<br />

der Harfe perfekt geeignet. Von Hugo de Lantins<br />

ist wenig bekannt, außer dass seine Blütezeit ungefähr<br />

zwischen 1420 und 1430 fällt und dass er vielleicht wie<br />

Loqueville Verbindungen mit Guillaume Dufay hatte. Und was<br />

kann man über Dufay, die Perle unter den <strong>Ko</strong>mponisten jenes<br />

Jahrhunderts, schreiben, dass nicht schon gesagt wurde? Sein<br />

Quel fronte signorille in paradiso bm ist ein perfektes Beispiel<br />

für die italienische Liebenswürdigkeit a la Francesca.<br />

CHRISTOPHER PAGE © 1988<br />

Übersetzung ELKE HOCKINGS, 2006<br />

Wenn Ihnen die vorliegende Aufnahme gefallen hat, lassen Sie sich unseren umfassenden Katalog von „Hyperion“- und „Helios“-Aufnahmen schicken.<br />

Ein Exemplar erhalten Sie kostenlos von: Hyperion Records Ltd., PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, oder senden Sie uns ein E-Mail unter info@hyperionrecords.co.uk.<br />

Wir schicken Ihnen gern gratis einen Katalog zu.<br />

Der Hyperion Katalog kann auch unter dem folgenden Internet Code erreicht werden: www.hyperion-records.co.uk<br />

Si vous souhaitez de plus amples détails sur ces enregistrements, et sur les nombreuses autres publications du label Hyperion, veuillez nous écrire à<br />

Hyperion Records Ltd, PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, England, ou nous contacter par courrier électronique à info@hyperion-records.co.uk, et nous<br />

serons ravis de vous faire parvenir notre catalogue gratuitement.<br />

Le catalogue Hypérion est également accessible sur Internet : www.hyperion-records.co.uk

Recorded in the Church of St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead, London, on 26 and 29 September 1987<br />

Recording Engineer TONY FAULKNER<br />

Recording Producer MARTIN COMPTON<br />

Executive Producer EDWARD PERRY<br />

P Hyperion Records Limited, London, 1988<br />

C Hyperion Records Limited, London, 2011<br />

(Originally issued on Hyperion CDA66286)<br />

Front illustration: ‘The Nine Heroines’ from Thomas of Saluzzo’s Chevalier Errant<br />

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS fr.12559, f.125v.<br />

All Hyperion and Helios recordings may be purchased over the internet at<br />

www.hyperion-records.co.uk<br />

where you can also listen to extracts from all recordings and browse an up-to-date catalogue<br />

Copyright subsists in all Hyperion recordings and it is illegal to copy them, in whole or in part, for any purpose whatsoever,<br />

without permission from the copyright holder, Hyperion Records Ltd, PO Box 25, London SE9 1AX, England. Any unauthorized<br />

copying or re-recording, broadcasting, or public performance of this or any other Hyperion recording will constitute an<br />

infringement of copyright. Applications for a public performance licence should be sent to Phonographic Performance Ltd,<br />

1 Upper James Street, London W1F 9DE<br />

15

A Song for Francesca<br />

MUSIC IN ITALY, 1330–1430<br />

1 ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA Astio non morì mai ballata RCC JMA LN [3'02]<br />

2 ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA Per la ver’onestà ballata MP RCC [4'35]<br />

3 ANONYMOUS Quando i oselli canta madrígal JMA LN [2'01]<br />

4 ANONYMOUS (Faenza codex) Constantia ALK [3'04]<br />

5 GIOVANNI DA CASCIA ‘JOHANNES DE FLORENTIA’ Quando la stella madrígal JMA LN [3'15]<br />

6 ANONYMOUS Amor mi fa cantar a la Francesca ballata RCC [2'34]<br />

7 ANONYMOUS (Faenza codex, after Jacopo da Bologna) Non na el so amante ALK [2'39]<br />

8 FRANCESCO LANDINI Ochi dolenti mie ballata RCC LN [2'52]<br />

9 FRANCESCO LANDINI Per seguir la sperança ballata MP RCC LN [3'38]<br />

French pieces from the Italian manuscript, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Canonici misc. 213<br />

bl ANONYMOUS O regina seculi / Reparatrix Maria MP CT RCC JMA LN [2'28]<br />

bm GUILLAUME DUFAY Quel fronte signorille in paradiso MP RCC JMA [2'36]<br />

bn RICHARD LOQUEVILLE Puisque je suy amoureux rondeau ALK [2'52]<br />

bo RICHARD LOQUEVILLE Pour mesdisans ne pour leur faulx parler ALK [1'52]<br />

bp HUGO DE LANTINS Plaindre m’estuet rondeau MP RCC LN [4'33]<br />

bq JOHANNNES HAUCOURT Je demande ma bienvenue rondeau MP CP [1'52]<br />

br ANONYMOUS Confort d’amours rondeau MP CT RCC LN [3'47]<br />

bs RICHARD LOQUEVILLE Qui ne veroit que vos deulx yeulx rondeau ALK [1'12]<br />

bt ESTIENNE GROSSIN Va t’ent souspir MP RCC LN [1'34]<br />

GOTHIC VOICES<br />

MARGARET PHILPOT contralto CAROLINE TREVOR alto<br />

ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP JOHN MARK AINSLEY LEIGH NIXON tenor<br />

CHRISTOPHER PAGE director / medieval harp<br />

with ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING medieval harp<br />

CDH55291

HELIOS<br />

CDH55291<br />

A SONG FOR FRANCESCA<br />

GOTHIC VOICES / CHRISTOPHER PAGE<br />

NOTES EN FRANÇAIS + MIT DEUTSCHEM KOMMENTAR<br />

‘Performances which stimulate the mind and invariably cosset the ear … these vibrant<br />

performances are matched by a fine recording in the Hyperion tradition’ (Gramophone)<br />

A Song for Francesca MUSIC IN ITALY, 1330–1430<br />

1 ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA Astio non morì mai ballata [3'02]<br />

2 ANDREAS DE FLORENTIA Per la ver’onestà ballata [4'35]<br />

3 ANONYMOUS Quando i oselli canta madrígal [2'01]<br />

4 ANONYMOUS (Faenza codex) Constantia [3'04]<br />

5 GIOVANNI DA CASCIA ‘JOHANNES DE FLORENTIA’ Quando la stella madrígal [3'15]<br />

6 ANONYMOUS Amor mi fa cantar a la Francesca ballata [2'34]<br />

7 ANONYMOUS (Faenza codex) Non na el so amante [2'39]<br />

8 FRANCESCO LANDINI Ochi dolenti mie ballata [2'52]<br />

9 FRANCESCO LANDINI Per seguir la sperança ballata [3'38]<br />

bl ANONYMOUS O regina seculi / Reparatrix Maria [2'28]<br />

bm GUILLAUME DUFAY Quel fronte signorille in paradiso [2'36]<br />

bn RICHARD LOQUEVILLE Puisque je suy amoureux rondeau [2'52]<br />

bo RICHARD LOQUEVILLE Pour mesdisans ne pour leur faulx parler [1'52]<br />

bp HUGO DE LANTINS Plaindre m’estuet rondeau [4'33]<br />

bq JOHANNNES HAUCOURT Je demande ma bienvenue rondeau [1'52]<br />

br ANONYMOUS Confort d’amours rondeau [3'47]<br />

bs RICHARD LOQUEVILLE Qui ne veroit que vos deulx yeulx rondeau [1'12]<br />

bt ESTIENNE GROSSIN Va t’ent souspir [1'34]<br />

GOTHIC VOICES with ANDREW LAWRENCE-KING medieval harp<br />

CHRISTOPHER PAGE director<br />

CDH55291<br />

Duration 50'29<br />

A HYPERION RECORDING<br />

DDD<br />

MADE IN FRANCE<br />

Recorded on 26 and 29 September 1987<br />

Recording Engineer TONY FAULKNER<br />

Recording Producer MARTIN COMPTON<br />

Executive Producer EDWARD PERRY<br />

P Hyperion Records Limited, London, 1988<br />

C Hyperion Records Limited, London, 2011<br />

(Originally issued on Hyperion CDA66286)<br />

Front illustration: ‘The Nine Heroines’ from Thomas of Saluzzo’s Chevalier Errant<br />

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, MS fr.12559, f.125v.<br />

A SONG FOR FRANCESCA<br />

GOTHIC VOICES / CHRISTOPHER PAGE<br />

HELIOS<br />

CDH55291