Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

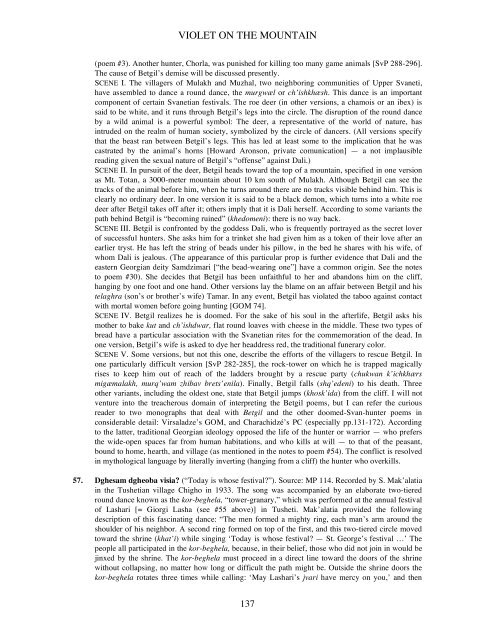

VIOLET ON THE MOUNTAIN<br />

(poem #3). Another hunter, Chorla, was punished for killing too many game animals [SvP 288-296].<br />

The cause of Betgil’s demise will be discussed presently.<br />

SCENE I. The villagers of Mulakh and Muzhal, two neighboring communities of Upper Svaneti,<br />

have assembled to dance a round dance, the murgwæl or ch’ishkhæsh. This dance is an important<br />

component of certain Svanetian festivals. The roe deer (in other versions, a chamois or an ibex) is<br />

said to be white, and it runs through Betgil’s legs into the circle. The disruption of the round dance<br />

by a wild animal is a powerful symbol: The deer, a representative of the world of nature, has<br />

intruded on the realm of human society, symbolized by the circle of dancers. (All versions specify<br />

that the beast ran between Betgil’s legs. This has led at least some to the implication that he was<br />

castrated by the animal’s horns [Howard Aronson, private comunication] — a not implausible<br />

reading given the sexual nature of Betgil’s “offense” against Dali.)<br />

SCENE II. In pursuit of the deer, Betgil heads toward the top of a mountain, specified in one version<br />

as Mt. Totan, a 3000-meter mountain about 10 km south of Mulakh. Although Betgil can see the<br />

tracks of the animal before him, when he turns around there are no tracks visible behind him. This is<br />

clearly no ordinary deer. In one version it is said to be a black demon, which turns into a white roe<br />

deer after Betgil takes off after it; others imply that it is Dali herself. According to some variants the<br />

path behind Betgil is “becoming ruined” (khedomeni): there is no way back.<br />

SCENE III. Betgil is confronted by the goddess Dali, who is frequently portrayed as the secret lover<br />

of successful hunters. She asks him for a trinket she had given him as a token of their love after an<br />

earlier tryst. He has left the string of beads under his pillow, in the bed he shares with his wife, of<br />

whom Dali is jealous. (The appearance of this particular prop is further evidence that Dali and the<br />

eastern Georgian deity Samdzimari [“the bead-wearing one”] have a common origin. See the notes<br />

to poem #30). She decides that Betgil has been unfaithful to her and abandons him on the cliff,<br />

hanging by one foot and one hand. Other versions lay the blame on an affair between Betgil and his<br />

telaghra (son’s or brother’s wife) Tamar. In any event, Betgil has violated the taboo against contact<br />

with mortal women before going hunting [GOM 74].<br />

SCENE IV. Betgil realizes he is doomed. For the sake of his soul in the afterlife, Betgil asks his<br />

mother to bake kut and ch’ishdwar, flat round loaves with cheese in the middle. These two types of<br />

bread have a particular association with the Svanetian rites for the commemoration of the dead. In<br />

one version, Betgil’s wife is asked to dye her headdress red, the traditional funerary color.<br />

SCENE V. Some versions, but not this one, describe the efforts of the villagers to rescue Betgil. In<br />

one particularly difficult version [SvP 282-285], the rock-tower on which he is trapped magically<br />

rises to keep him out of reach of the ladders brought by a rescue party (chukwan k’ichkhærs<br />

migæmalakh, murq’wam zhibav brets’enila). Finally, Betgil falls (shq’edeni) to his death. Three<br />

other variants, including the oldest one, state that Betgil jumps (khosk’ida) from the cliff. I will not<br />

venture into the treacherous domain of interpreting the Betgil poems, but I can refer the curious<br />

reader to two monographs that deal with Betgil and the other doomed-Svan-hunter poems in<br />

considerable detail: Virsaladze’s GOM, and Charachidzé’s PC (especially pp.131-172). According<br />

to the latter, traditional Georgian ideology opposed the life of the hunter or warrior — who prefers<br />

the wide-open spaces far from human habitations, and who kills at will — to that of the peasant,<br />

bound to home, hearth, and village (as mentioned in the notes to poem #54). The conflict is resolved<br />

in mythological language by literally inverting (hanging from a cliff) the hunter who overkills.<br />

57. Dghesam dgheoba visia? (“Today is whose festival?”). Source: MP 114. Recorded by S. Mak’alatia<br />

in the Tushetian village Chigho in 1933. The song was accompanied by an elaborate two-tiered<br />

round dance known as the kor-beghela, “tower-granary,” which was performed at the annual festival<br />

of Lashari [= Giorgi Lasha (see #55 above)] in Tusheti. Mak’alatia provided the following<br />

description of this fascinating dance: “The men formed a mighty ring, each man’s arm around the<br />

shoulder of his neighbor. A second ring formed on top of the first, and this two-tiered circle moved<br />

toward the shrine (khat’i) while singing ‘Today is whose festival? — St. George’s festival …’ The<br />

people all participated in the kor-beghela, because, in their belief, those who did not join in would be<br />

jinxed by the shrine. The kor-beghela must proceed in a direct line toward the doors of the shrine<br />

without collapsing, no matter how long or difficult the path might be. Outside the shrine doors the<br />

kor-beghela rotates three times while calling: ‘May Lashari’s jvari have mercy on you,’ and then<br />

137