- Page 1 and 2: LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS LECTURE NOTES A

- Page 3 and 4: PREFACE This book is not a traditio

- Page 5 and 6: TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface. . . . .

- Page 7 and 8: 3.3 Traditional and Structural Gram

- Page 9 and 10: INTRODUCTION: LINGUISTICS AND THE J

- Page 11 and 12: college and career readiness (The M

- Page 13 and 14: (3) a. Should colleagues be discipl

- Page 15 and 16: elationship between gas mileage and

- Page 17 and 18: Several years ago, Ford Motor Compa

- Page 19 and 20: Since the principles in (9) are obj

- Page 21 and 22: Now notice that there are actually

- Page 23 and 24: Since language is a product of huma

- Page 25 and 26: Native speakers of English understa

- Page 27 and 28: to introduce students to systematic

- Page 29: Work for an advertising company: Co

- Page 32 and 33: 24 Again, there is a specific princ

- Page 34 and 35: 26 When people read the sentences i

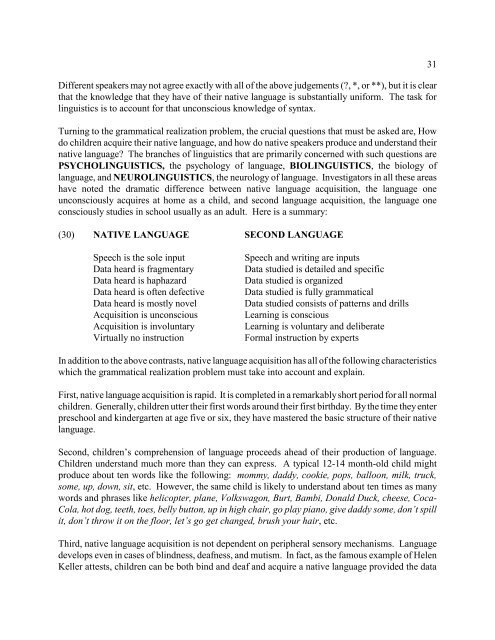

- Page 36 and 37: 28 1.2 THE BRANCHES OF GRAMMAR AND

- Page 40 and 41: 32 of the language gets into the ch

- Page 42 and 43: 34 c. Time Three - about three mont

- Page 44 and 45: 36 in all areas of development, inc

- Page 46 and 47: 38 judgements about grammar, which

- Page 48 and 49: 40 1.6 LINGUISTIC ARGUMENTATION Lin

- Page 50 and 51: 42 The diagram in (37) is a proposa

- Page 52 and 53: 44 or, at least, readily clear afte

- Page 54 and 55: 46 1.7 UNIVERSAL GRAMMAR (UG) The d

- Page 56 and 57: 48 UG contains two types of univers

- Page 58 and 59: 50 While languages do have syntacti

- Page 60 and 61: 52 At the level of descriptive adeq

- Page 62 and 63: 54 verification for this distributi

- Page 64 and 65: 56 the p’s in tiptop). Therefore,

- Page 66 and 67: 58 (74) a. [Something] pleased the

- Page 68 and 69: 60 1.10 THE GENERALITY OF LINGUISTI

- Page 70 and 71: 62 As a third example of the genera

- Page 72 and 73: 64 As a fifth example of the genera

- Page 74 and 75: 66 c. Ungrammatical and Unacceptabl

- Page 76 and 77: 68 (98) RIGHT BRANCHING CONSTRUCTIO

- Page 78 and 79: 70 1.12 LANGUAGE VARIATION All huma

- Page 80 and 81: 72 Why not form direct questions in

- Page 82 and 83: 74 1.14 TYPES OF LANGUAGES It is na

- Page 84 and 85: 76 (116) AMBIGUITY (one sound, more

- Page 86 and 87: 78 Or consider which of the followi

- Page 88 and 89:

80 Neurological Changes Let us cons

- Page 90 and 91:

82 animals can do; therefore, it is

- Page 92 and 93:

84 We do not find such optimally ef

- Page 94 and 95:

86 thing, i.e., ambiguities like (1

- Page 96 and 97:

88 EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER ONE 1. Wha

- Page 98 and 99:

90 5. Find the words which express

- Page 100 and 101:

92 Can you think of other ways of d

- Page 102 and 103:

94 FIGURE ONE: THE VOCAL APPARATUS

- Page 104 and 105:

96 feature [±ROUND] to distinguish

- Page 106 and 107:

98 MANNER OF ARTICULATION STOP [-VO

- Page 108 and 109:

100 2.1.2.4 NASALS A fourth group o

- Page 110 and 111:

102 FIGURE SIX: DISTINCTIVE FEATURE

- Page 112 and 113:

104 articulation, but they are diff

- Page 114 and 115:

106 As these examples show, a sylla

- Page 116 and 117:

108 In examining English, phonologi

- Page 118 and 119:

110 [2] [+ASPIRATED] considerable b

- Page 120 and 121:

112 The necessity for both levels o

- Page 122 and 123:

114 2.3 PHONOTACTICS Further invest

- Page 124 and 125:

116 Morphemes have different phonet

- Page 126 and 127:

118 Notice that (30) involves a cha

- Page 128 and 129:

120 (32) a. The PST morpheme in Eng

- Page 130 and 131:

122 (45) a. If a suffix and the fin

- Page 132 and 133:

124 Vowels have many redundant feat

- Page 134 and 135:

126 Similarly, silent letters frequ

- Page 136 and 137:

128 VOWELS: SUMMARY OF ENGLISH SOUN

- Page 138 and 139:

EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER TWO 1. Transc

- Page 140 and 141:

132 2. Transcribe the following Eng

- Page 142 and 143:

134 runaway Saturday ricochet prot

- Page 144 and 145:

136 h. tense high front unrounded v

- Page 146 and 147:

138 b. Nontense vowels in the final

- Page 148 and 149:

140 12. Consider the following addi

- Page 150 and 151:

142 weird feared veered cared cord

- Page 152 and 153:

144 3. agree debris ennui Pawnee ma

- Page 154 and 155:

146 APPENDIX B: PHONOLOGICAL RULES

- Page 156 and 157:

148 d. e. 8. a. Nasalize all vowels

- Page 158 and 159:

150 APPENDIX D: PHONOLOGY PROBLEM D

- Page 160 and 161:

152 APPENDIX F: ENGLISH VOWEL SHIFT

- Page 162 and 163:

154 (3) Root /fræg/ ‘break’: a

- Page 164 and 165:

156 about commands, people often as

- Page 166 and 167:

158 verified or falsified through a

- Page 168 and 169:

160 so the example is ambiguous. We

- Page 170 and 171:

162 3.2 ORDERING CONSTRAINTS With t

- Page 172 and 173:

164 OMISSION is the deletion of a p

- Page 174 and 175:

166 3.2.2 THREE OTHER DIAGNOSTICS T

- Page 176 and 177:

168 Given the reality of the chunk

- Page 178 and 179:

170 If AUX is part of the VERB PHRA

- Page 180 and 181:

172 (69) a. Generally the passenger

- Page 182 and 183:

174 (74) a. The new tenor from Ital

- Page 184 and 185:

176 Additional facts about tense th

- Page 186 and 187:

178 3.5 DETERMINERS AND THE INTERNA

- Page 188 and 189:

180 The grammar we are developing m

- Page 190 and 191:

182 In other words, determiners and

- Page 192 and 193:

184 constituents; braces indicate a

- Page 194 and 195:

186 3.6 THE ENDOCENTRICITY CONSTRAI

- Page 196 and 197:

188 3.7 THE LEXICON In order to gen

- Page 198 and 199:

190 (128) a. We made double the pro

- Page 200 and 201:

192 Astronomy is one of the oldest

- Page 202 and 203:

194 If we attempt to diagram the NP

- Page 204 and 205:

196 Note that each bracket on the l

- Page 206 and 207:

198 The data that we have observed

- Page 208 and 209:

200 Given these structures, we can

- Page 210 and 211:

202 The problem with the structures

- Page 212 and 213:

204 b. He decided on the boat. (on

- Page 214 and 215:

206 With this revision, we can diag

- Page 216 and 217:

208 With all the above revisions, i

- Page 218 and 219:

210 Summarizing, we have the follow

- Page 220 and 221:

212 The feature [+VBL] specifies th

- Page 222 and 223:

214 Within a particular kind of phr

- Page 224 and 225:

216 Since all categories on the X2

- Page 226 and 227:

218 (208) a. The school shows play

- Page 228 and 229:

220 The representations in (212) an

- Page 230 and 231:

222 Observe again that, by conventi

- Page 232 and 233:

224 In Japanese, a head final langu

- Page 234 and 235:

226 The complete RG morphosyntactic

- Page 236 and 237:

228 Given (231), we have solved the

- Page 238 and 239:

230 The need for three X levels abo

- Page 240 and 241:

232 The three level hypothesis for

- Page 242 and 243:

234 c. The boys made good models. [

- Page 244 and 245:

236 are two types of verbs in Engli

- Page 246 and 247:

238 3.14 NONTRANSFORMATIONAL GENERA

- Page 248 and 249:

240 The phrase “immediately C-com

- Page 250 and 251:

242 3.16 EMPTY CATEGORIES As we hav

- Page 252 and 253:

244 (285) a. What i did the teacher

- Page 254 and 255:

246 Note that the matter is not sim

- Page 256 and 257:

248 (308) a. John pushed the door o

- Page 258 and 259:

250 Returning to the main theme, su

- Page 260 and 261:

252 c. VOS. [ [ [ [ [ amat] ][ PRS]

- Page 262 and 263:

254 3.17.3 THE ORDERING OF V1 CONST

- Page 264 and 265:

256 This frame says that the order

- Page 266 and 267:

258 (352) a. He needs to give vent

- Page 268 and 269:

260 f. Further examples of particip

- Page 270 and 271:

262 3.18.2 PROBLEMS WITH THE CLASSI

- Page 272 and 273:

264 This do must be distinguished f

- Page 274 and 275:

266 If we treat be as a main verb a

- Page 276 and 277:

268 The above analysis solves a mul

- Page 278 and 279:

270 (398) a. Have they done that? b

- Page 280 and 281:

272 Given (408), we see that all us

- Page 282 and 283:

274 3.18.5 PARSES ILLUSTRATING THE

- Page 284 and 285:

276 (422) Present Tense + Perfectiv

- Page 286 and 287:

278 (425) Conditional Tense + Perfe

- Page 288 and 289:

280 (427) Conditional Tense + Perfe

- Page 290 and 291:

282 EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER THREE 1.

- Page 292 and 293:

284 Provide disambiguating diagrams

- Page 294 and 295:

286 APPENDIX A: ANSWERS TO EXERCISE

- Page 296 and 297:

288 h. The boy could take the garba

- Page 298 and 299:

290 4. All of the following sentenc

- Page 300 and 301:

292 (2) = The man will look the str

- Page 302 and 303:

294 7. Draw RG diagrams for the fol

- Page 304 and 305:

296 h. The boy could take the garba

- Page 306 and 307:

298 c. They will probably read the

- Page 308 and 309:

300 b. Ron left the house messy. (1

- Page 310 and 311:

302 d. The prisoner of war spoke fo

- Page 312 and 313:

304 APPENDIX B: LATIN SYNTAX Latin

- Page 314 and 315:

306 APPENDIX C: SUMMARY OF TREE STR

- Page 316 and 317:

308 7. Sentence with an intransitiv

- Page 318 and 319:

310 DEMONSTRATIVE PRONOUNS are used

- Page 320 and 321:

312 MORPHOLOGY Most grammars divide

- Page 322 and 323:

314 SUPPLEMENT TWO (PART I): TYPOLO

- Page 324 and 325:

316 GERMANIC: SUPPLEMENT THREE (PAR

- Page 326 and 327:

318 SUPPLEMENT FOUR (PART I): LANGU

- Page 328 and 329:

320 SUPPLEMENT FOUR (PART III): IND

- Page 330 and 331:

322 SUPPLEMENT FOUR (PART V): OTHER

- Page 332 and 333:

324 Luiseño [II] Luo [I] Maasai [I

- Page 334 and 335:

326

- Page 336 and 337:

328 (2) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT C

- Page 338 and 339:

330 (4) COPULATIVE (PREDICATE COMPL

- Page 340 and 341:

332 (6) INTRANSITIVE WITH PREDICATE

- Page 342 and 343:

334 (8) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT +

- Page 344 and 345:

336 b. TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT +

- Page 346 and 347:

338 (11) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT

- Page 348 and 349:

340 (13) TRANSITIVE (DOUBLE OBJECT)

- Page 350 and 351:

342 (15) TRANSITIVE (SENTENTIAL COM

- Page 352 and 353:

344 The clause “I know that man i

- Page 354 and 355:

346 (18) TRANSITIVE (SENTENTIAL COM

- Page 356 and 357:

348 (20) TRANSITIVE (SENTENTIAL COM

- Page 358 and 359:

350 (22) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT

- Page 360 and 361:

352 (24) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT

- Page 362 and 363:

354 (26) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT

- Page 364 and 365:

356 (28) INTRANSITIVE (PREPOSITIONA

- Page 366 and 367:

358 (30) TRANSITIVE (PARTICLE + DIR

- Page 368 and 369:

360 (32) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT

- Page 370 and 371:

362 (34) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT

- Page 372 and 373:

364 (36) TRANSITIVE (PREPOSITIONAL

- Page 374 and 375:

366 (2) The kitchen appliance facto

- Page 376 and 377:

368 (6) The soprano from a small to

- Page 378 and 379:

370 (2) We believe John to be compl

- Page 380 and 381:

372 SUPPLEMENT TEN: SAMPLE PARSES F

- Page 382 and 383:

374 (3) Gerundial Nominals (-ing) a

- Page 384 and 385:

376 (5) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT +

- Page 386 and 387:

378 (7) TRANSITIVE (DIRECT OBJECT +

- Page 388 and 389:

380 The clause “I heard the tenor

- Page 390 and 391:

382 (4) Structural Representation:

- Page 392 and 393:

384 (9) Binding Relations: a. Chain

- Page 394 and 395:

386 k. The Subject Exclusion Condit

- Page 396 and 397:

388 (8) X3 elements are SPECIFIERS

- Page 398 and 399:

390 (11) TG (Transformational Gramm

- Page 400 and 401:

392 (13) RG (Residential Grammar) A

- Page 402 and 403:

394 MERGING FRAMES Merge 138 & 330

- Page 404 and 405:

396

- Page 406 and 407:

398 Bresnan, Joan. 1973. “The Syn

- Page 408 and 409:

400 Halle, Morris, Joan Bresnan, an

- Page 410 and 411:

402

- Page 412 and 413:

404 1. Evidence for cerebral latera

- Page 414 and 415:

406 11. A major defect of quantitat

- Page 416 and 417:

408 21. Which of the following is a

- Page 418 and 419:

410 32. When linguists attempt to r

- Page 420 and 421:

412 43. Pivot words are a. high in

- Page 422 and 423:

SAMPLE TEST TWO LIN 180: LINGUISTIC

- Page 424 and 425:

416 5. Which of the following is th

- Page 426 and 427:

418 13. Which of the following is a

- Page 428 and 429:

420 21. Consider the following rule

- Page 430 and 431:

422 26. Which of the following rule

- Page 432 and 433:

424 30. The word indescribable has

- Page 434 and 435:

426 36. Which of the following is c

- Page 436 and 437:

428 43. Which of the following rule

- Page 438 and 439:

430 47. Which of the following feat

- Page 440 and 441:

SAMPLE TEST THREE LIN 180: LINGUIST

- Page 442 and 443:

3. Consider the following sentences

- Page 444 and 445:

8. In terms of all that we have dis

- Page 446 and 447:

12. Which of the following noun phr

- Page 448 and 449:

17. Which of the following sets of

- Page 450 and 451:

THE NEXT FOUR QUESTIONS (24 - 27) R

- Page 452 and 453:

30. If a sentence has the above str

- Page 454 and 455:

37. Which of the following is corre

- Page 456 and 457:

44. Which of the following sentence

- Page 458 and 459:

SAMPLE TEST FOUR LIN 180: LINGUISTI

- Page 460 and 461:

3. Consider the following sentences

- Page 462 and 463:

8. In terms of all that we have dis

- Page 464 and 465:

12. Which of the following sentence

- Page 466 and 467:

17. Which of the following sets of

- Page 468 and 469:

THE NEXT FOUR QUESTIONS (24 - 27) R

- Page 470 and 471:

30. If a sentence has the above str

- Page 472 and 473:

37. Which of the following nodes C-

- Page 474 and 475:

44. Which of the following is part

- Page 476 and 477:

INDEX Abstract Noun. . . . . . . .

- Page 478 and 479:

Exclamatory. . . . . . . . . . . .

- Page 480 and 481:

Natural Class. . . . . . . . . . .

- Page 482 and 483:

Release. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- Page 484 and 485:

THE LANGTECH PARSER Enter a sentenc

- Page 486:

478