linguistic analysis - Professor Binkert's Webpage - Oakland University

linguistic analysis - Professor Binkert's Webpage - Oakland University

linguistic analysis - Professor Binkert's Webpage - Oakland University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

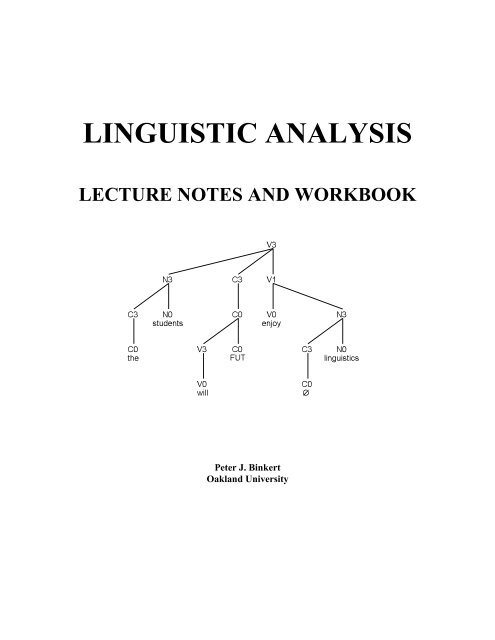

LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS<br />

LECTURE NOTES AND WORKBOOK<br />

Peter J. Binkert<br />

<strong>Oakland</strong> <strong>University</strong>

Copyright © The Langtech Corporation 2012<br />

The Langtech Corporation<br />

643 Hazy View Lane<br />

Milford, Michigan 48381-2159<br />

All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. Except for the<br />

quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication<br />

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,<br />

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior<br />

permission in writing from the publisher.

PREFACE<br />

This book is not a traditional introductory textbook for <strong>linguistic</strong>s. Although many of the traditional<br />

topics are discussed in the following chapters, the book does not aim at a comprehensive summary<br />

of the discipline. Rather, the intent is to present to the student a unified theory of human language<br />

which demonstrates specifically that the structure of human language is not arbitrary and that it<br />

derives directly from genetically determined faculties of human beings. The essential nature of<br />

human language is not a matter of choice, convention, or whim. Cultural diversity among different<br />

societies and <strong>linguistic</strong> diversity among different languages and dialects reflect superficial variations<br />

on this basic, biologically determined structure.<br />

The central theme of this text is quite simple: human language reflects the capacities and limitations<br />

of human beings. There are three facts supporting this theme. First, all normal human beings,<br />

regardless of the languages they speak and the cultures they represent, have the same basic biological<br />

makeup. Second, all children learn whatever language they are exposed to in whatever cultural<br />

setting; children are not predestined to learn specific languages. Third, language acquisition in all<br />

children proceeds in a uniform and predictable fashion despite widely varying environmental<br />

conditions.<br />

These facts clearly indicate that the structure of all languages must be based on the nature of human<br />

beings. This is not an original idea; indeed, much of the current work in <strong>linguistic</strong>s in all theoretical<br />

frameworks proceeds from this position. For example, it is basic to Noam Chomsky’s concept of<br />

<strong>linguistic</strong> universals.<br />

Where this text differs from most introductory texts is in the manner in which the various<br />

subdivisions within <strong>linguistic</strong>s are described. At every point possible, the development of our theme<br />

will be bolstered by specific arguments that have reference to human biology and psychology. All<br />

components of language will be related to each other, rather than presented as discrete units, so that<br />

elements of <strong>linguistic</strong> structure, change, and variation are integrated. Our discussion of different<br />

languages and different cultures will show how <strong>linguistic</strong> divergence is constrained by <strong>linguistic</strong><br />

universals.<br />

Generally, <strong>linguistic</strong>s departments on university campuses are grouped with the social sciences<br />

(psychology, sociology, anthropology, etc.) or humanities (philosophy, music, art, literature, etc.).<br />

In either of these contexts, <strong>linguistic</strong>s is in a distinctive position to make contributions to the history<br />

of ideas. Linguistic argumentation, that is, the justification of grammars, is a highly developed<br />

methodology that can be used to make predictions about the nature of man and mind. Traditional<br />

justification of theoretical models in the natural and physical sciences derives from experimentation.<br />

The techniques of justification in biology and physics are familiar to every student. In <strong>linguistic</strong>s<br />

also, it is possible to formulate hypotheses of considerable rigor and subject them to scientific<br />

scrutiny that leads directly to their verification or refutation. This book aims to show the<br />

introductory student how this is possible.

More than anything else, this text is designed to disabuse readers of the many misconceptions that<br />

surround the study of language. These fallacies include, among other things, the idea that different<br />

dialects, different cultural patterns, and even different languages reflect different levels of human<br />

competence, as well as the prevalent idea that grammatical structure is haphazard and unjustifiable.<br />

Although it may be difficult to believe at this point, the study of grammar can lead to provocative<br />

and interesting ideas about the nature of human beings and the origin of cultural diversity.<br />

Needless to say, one cannot attain such a high level of generality about language, or anything else,<br />

without attention to detail. Therefore, in the following chapters, students will be introduced to some<br />

of the technical vocabulary of <strong>linguistic</strong>s. The aim is not to memorize facts per se, although mastery<br />

of some details is essential before application can begin; rather, it is to show how rigorous<br />

investigation can lead to meaningful generalizations. Lists of memorized facts rarely stay in people’s<br />

minds for very long, but genuine comprehension of issues does. Moreover, such comprehension can<br />

have a significant impact on one’s life. In this regard, this text aims to satisfy some of the major<br />

objectives of general education, which include, among other things, helping students understand and<br />

master basic techniques for the <strong>analysis</strong> and synthesis of ideas. Such techniques involve the ability<br />

to gather, organize, and interpret data, to separate what is significant and interesting from what is<br />

irrelevant and trivial, and to formulate hypotheses of real explanatory power. Effective thinking<br />

occurs when one is able to uncover the essential nature of any given problem and to propose<br />

reasonable solutions consistent with available resources.<br />

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Preface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i<br />

Table of Contents.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii<br />

Introduction: Linguistics and the Job Market. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1<br />

Chapter One: Fundamentals of Linguistics.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23<br />

1.1 Grammatical Characterization and Grammatical Realization. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23<br />

1.2 The Branches of Grammar and Linguistics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28<br />

1.3.1 Native Language Acquisition and Maturation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36<br />

1.3.2 Cerebral Lateralization.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36<br />

1.4 The Study of Grammar. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38<br />

1.5 Speech and Writing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39<br />

1.6 Linguistic Argumentation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40<br />

1.6.1 Diagnostics.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41<br />

1.6.2 Justifying Structure: Units. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41<br />

1.6.3 Justifying Structure: Labels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44<br />

1.7 Universal Grammar (UG). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46<br />

1.8 Levels of Adequacy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51<br />

1.9 Relating Linguistic Competence and Linguistic Performance.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56<br />

1.10 The Generality of Linguistic Universals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60<br />

1.11 Linguistic Universals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67<br />

1.12 Language Variation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70<br />

1.13 Language and Culture. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71<br />

1.14 Types of Languages. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74<br />

1.15 The Evolution of Human Language.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78<br />

Exercises for Chapter One. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88<br />

Chapter Two: Phonetics and Phonology.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93<br />

2.1 Phonetics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93<br />

2.1.1 Vowels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93<br />

Figure One: the Vocal Apparatus.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94<br />

Figure Two: English Vowels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95<br />

Figure Three: Distinctive Features for English Vowels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96<br />

2.1.2 Consonants.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97<br />

Figure Four: English Consonants, Liquids, and Glides. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98<br />

2.1.3 Liquids and Glides. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Figure Five: The Major Phonological Categories. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100<br />

Figure Six: Distinctive Features for English Consonants, Liquids & Glides. . . . . . . . . 102<br />

2.1.4 Review of Issues. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103<br />

2.1.5 Suprasegmentals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105<br />

2.1.6 Syllables.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105<br />

2.2 Phonology. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107<br />

Figure Seven: Phonological and Phonetic Representations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113<br />

2.3 Phonotactics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114<br />

2.4 Morphology. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115<br />

2.5 The Biological Basis of Phonology. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117<br />

2.5.1 First Set of Observations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119<br />

2.5.2 Second Set of Observations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121<br />

2.5.3 Third Set of Observations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123<br />

2.6 The Phonological and Lexical Components of a Grammar.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123<br />

2.7 English Spelling.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125<br />

2.8 Summary of Rule Formalism.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127<br />

2.9 Notes on Syllables. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127<br />

Summary of English Sounds and Spelling.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128<br />

Exercises for Chapter Two.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130<br />

Appendix A: Answers to Transcription Exercises.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141<br />

Appendix B: Phonological Rules.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146<br />

Appendix C: Slash–dash Notation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149<br />

Appendix D: Phonology Problem.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150<br />

Appendix E: Morphology Problem.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151<br />

Appendix F: English Vowel Shift. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152<br />

Appendix G: English Morphology.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153<br />

Chapter Three: Syntax. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155<br />

3.1 Linguistic Argumentation Revisited. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155<br />

3.1.1 Linguistic Argumentation: Sentence Types. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155<br />

3.1.2 Linguistic Argumentation: Parts of Speech. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158<br />

3.1.3 Linguistic Argumentation: Phrases.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159<br />

3.1.4 Linguistic Argumentation: Strategies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161<br />

3.2 Ordering Constraints. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162<br />

3.2.1 Testing Hypotheses: Reference, Omission, and Placement. . . . . . . . . . . 163<br />

3.2.2 Three Other Diagnostics to Determine Structure.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166<br />

3.2.3 Language and Memory.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167<br />

iv

3.3 Traditional and Structural Grammar. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 168<br />

3.4 Tense and the Internal Structure of Sentences. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174<br />

3.5 Determiners and the Internal Structure of Noun Phrases.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178<br />

3.5.1 Abstract Elements: Ø. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 179<br />

3.5.2 Phrase Structure Rules: First Proposal.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183<br />

3.6 The Endocentricity Constraint. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186<br />

3.7 The Lexicon. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 188<br />

3.8 A Note on Scientific Inquiry. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191<br />

3.9 X–bar Syntax. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193<br />

3.10 Generalizing Phrase Structure: S and NP. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198<br />

3.11 Adjuncts (Modifiers) and Complements. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200<br />

3.12 Residential Grammar (RG). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211<br />

Figure Eight: Features for Some English Morphosyntactic Categories.. . . . . . . . . . . . . 227<br />

3.13 Transformational Generative Grammar. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235<br />

3.14 Nontransformational Generative Grammar. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 238<br />

3.15 Command Relations in Phrase Structure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239<br />

3.16 Empty Categories.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242<br />

3.17 Word Order Variations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247<br />

3.17.1 Adverbs in French and Italian. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247<br />

3.17.2 Nonconfigurational Languages. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251<br />

3.17.3 The Ordering of V1 Constituents in Italian and Hebrew . . . . . . . . . . . . 254<br />

3.18 The English Auxiliary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259<br />

3.18.1 The Facts and Generalizations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259<br />

3.18.2 Problems with the Classic TG Analysis.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 262<br />

3.18.3 Resolution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 270<br />

3.18.4 Summary of Nominals and Verbals in RG. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273<br />

3.18.5 Parses Illustrating the English Auxiliary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 274<br />

Exercises for Chapter Three.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 282<br />

Appendix A: Answers to Exercises. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 286<br />

Appendix B: Latin Syntax .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 304<br />

Appendix C: Summary of Tree Structures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 306<br />

Supplement One: Grammar Review. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309<br />

Syntactic Categories (The Parts of Speech). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309<br />

Syntactic Constructions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 311<br />

Morphology. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 312<br />

Some Inflectional Categories. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 313<br />

v

Supplement Two (Part I): Typological Classification. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 314<br />

Supplement Two (Part II): Typological Classification. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 315<br />

Supplement Three (Part I): Historical Classification. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 316<br />

Supplement Three (Part II): Historical Classification.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317<br />

Supplement Four (Part I): Languages of Africa and the mid East. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 318<br />

Supplement Four (Part II): American Indian Languages. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319<br />

Supplement Four (Part III): Indo–european Languages.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 320<br />

Supplement Four (Part IV): Languages of East Asia & the Pacific.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 321<br />

Supplement Four (Part V): Other Languages of Europe and Asia.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 322<br />

Supplement Five: Languages and Language Groups. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 323<br />

Supplement Six: Some Alphabets. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 325<br />

Supplement Seven: Sample Parses from the Langtech Parser.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 327<br />

Sample Parses Illustrating Basic Sentence Patterns.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 327<br />

Supplement Eight: Sample Parses from the Langtech Parser. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 365<br />

Sample Parses Illustrating Noun Phrases.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 365<br />

Supplement Nine: Sample Parses from the Langtech Parser.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369<br />

Empty Categories: Ø, [u], and [e].. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 369<br />

Supplement Ten: Sample Parses from the Langtech Parser.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 372<br />

Sample Parses Illustrating Verbals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 372<br />

Outline of Technical Terms. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 381<br />

Residential Grammar (RG) Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 387<br />

References. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 397<br />

Sample Test One. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 403<br />

Sample Test Two. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 414<br />

Sample Test Three. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 432<br />

Sample Test Four. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 450<br />

Index. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 468<br />

vi

INTRODUCTION: LINGUISTICS AND THE JOB MARKET<br />

There is no doubt about it: high school graduates are having a very difficult time finding a job that<br />

pays well and gives them some prospects for advancement. A recent article in the New York Times<br />

(June 6, 2012), summarized the current situation as follows:<br />

“For this generation of young people, the future looks bleak. Only one in six is working full<br />

time. Three out of five live with their parents or other relatives. A large majority – 73 percent<br />

– think they need more education to find a successful career, but only half of those say they<br />

will definitely enroll in the next five years... For this group, finding work that pays a living<br />

wage and offers some sense of security has been elusive.” (More Young Americans out of<br />

High School Are Also out of Work, C. Rampell)<br />

Even among college graduates, the competition for jobs in today’s market is intense. According to<br />

an Associated Press news story on April 25, 2012, half of all new graduates are either jobless or<br />

underemployed:<br />

“In the last year, [graduates] were more likely to be employed as waiters, waitresses,<br />

bartenders and food-service helpers than as engineers, physicists, chemists and mathematicians<br />

combined (100,000 versus 90,000). There were more working in office-related jobs such as<br />

receptionist or payroll clerk than in all computer professional jobs (163,000 versus 100,000).<br />

More also were employed as cashiers, retail clerks and customer representatives than engineers<br />

(125,000 versus 80,000).<br />

“According to government projections released last month, only three of the 30 occupations<br />

with the largest projected number of job openings by 2020 will require a bachelor’s degree or<br />

higher to fill the position – teachers, college professors and accountants. Most job openings<br />

are in professions such as retail sales, fast food and truck driving, jobs which aren’t easily<br />

replaced by computers.” (Recent College Graduates Finding Few Job Prospects, Hope Yen,<br />

Associated Press, www.detroitnews.com/article/20120425)<br />

Despite these numbers, college graduates still fare better than those without degrees according to the<br />

Bureau of Labor Statistics (Yes, A College Education Is Worth the Costs, Rodney K. Smith, USA<br />

Today, 2011, www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/forum/story/2011-12-06/). Unemployment rates<br />

decrease as education increases (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010, www.bls.gov):<br />

•14.9% of those without a high school diploma<br />

•10.3% of those with a high school education<br />

•7% of those with an associate degree<br />

•5.4% of those with a bachelor’s degree<br />

•2.4% of those with a professional degree<br />

•1.9% of those with a doctoral degree.

2<br />

Also, educational attainment correlates with income. Here’s the average weekly income for those<br />

who have jobs (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010, www.bls.gov):<br />

•$444 for those with less than a high school degree<br />

•$626 for those with a high school degree<br />

•$767 for those with an associate degree<br />

•$1,038 for those with a bachelor’s degree<br />

•$1,550 for those with a doctoral degree<br />

Clearly, making the most out of a college education is crucial. Before choosing a program of study,<br />

students should spend some time surfing the internet and googling such search items as “what<br />

employers want,” “skills needed for the workplace,” “trends in the marketplace,” and so on. There<br />

are many myths and traditions surrounding options like the choice of a major in college. For<br />

example, students often think that it will be impossible to get a job in a specific discipline unless<br />

they study that discipline in depth in college. They cannot, for instance, become a manager unless<br />

they are a business major. Actually, careers often have little to do with specific majors in college.<br />

The Employee Benefits Research Institute, reports that the average tenure for all wage and salary<br />

workers age 25 or older was 5.2 years in 2010, compared with 5.0 years in 1983 (www.ebri.<br />

org/publications, Vol 31, No 12, 2010). That means that in the United States for nearly three<br />

decades workers generally stayed at the same job for about 5 years. As a result, if individuals work<br />

for 50 years, they can expect to have about 10 different jobs during their working careers. Different<br />

sources report slightly different statistics, but surfing the internet clearly shows that frequent job and<br />

career change is the norm in today’s market.<br />

Such change is in stark contrast to the situation in the past when individuals not only kept the same<br />

job for their entire lives but also had the same job as their parents and grandparents whether they be<br />

policemen, farmers, teachers, doctors, coal miners, etc. Nowadays, on the other hand, people can<br />

expect to change not only the company they work for but actually the type of work they do, that is,<br />

change their careers. Thus, one of the first things students should consider in choosing a program<br />

of study is finding one that can provide them with the skills to be adaptable, flexible, and mobile in<br />

a global and unpredictable economy. It is unlikely that the job a student finds after graduation will<br />

be directly linked to the course content of a specific undergraduate major.<br />

Problem Solving Skills Needed for the Workplace<br />

What exactly are the skills that will prepare a student to be adaptable, flexible, and mobile? One way<br />

to answer that question is to look at the kinds of skills that various employers look for. Again,<br />

surfing the internet, one finds that employers across the board look for many of the same skills in<br />

their employees. Chief among these skills is the ability to solve problems. For example, one survey<br />

of 301 executives in Fortune 1000 companies found that 99% of the executives think that the ability<br />

to solve problems and to think critically is either an absolutely essential or very important skill for

college and career readiness (The MetLife Survey of the American Teacher: Preparing Students for<br />

College and Careers, 2011, p. 21).<br />

Other studies also emphasize the importance of creative problem-solving skills. “Employers know<br />

that in business, the chessboard changes daily. As soon as we think all is fine, the economy changes<br />

or the competition makes a surprise move and the company’s own strategy must change,” said Mark<br />

Stevens, author of Your Marketing Sucks (Crown Business, 2003) and CEO of MSCO, a global<br />

marketing firm. “A person who gets locked into a set way of doing things finds it difficult or<br />

impossible to adjust. They are a drag on the business as opposed to an asset for it. [An employee<br />

must know] how to tackle challenges and opportunities in a way no one will find in a textbook.”<br />

(CNN: Top 10 Reasons Employers Want to Hire You, Rachel Zupek, www.CareerBuilder.com,<br />

2011).<br />

A multitude of sources including magazine articles, newspapers, on-line reports, scholarly papers,<br />

and books all suggest that critical thinking and problem solving skills are essential for success in<br />

today’s job market. There is also general agreement on what such skills entail. Two on-line sources<br />

define the necessary skills as follows:<br />

(1) Quintessential Careers: What Do Employers Really Want? Top Skills and Values<br />

Employers Seek from Job-Seekers, Randall Hansen and Katharine Hansen<br />

(www.quintcareers.com, 2012).<br />

a. Analytical/Research Skills. Deals with your ability to assess a situation, seek<br />

multiple perspectives, gather more information if necessary, and identify key issues<br />

that need to be addressed. Highly analytical thinking with demonstrated talent for<br />

identifying, scrutinizing, improving, and streamlining complex work processes.<br />

b. Problem-Solving/Reasoning/Creativity. Involves the ability to find solutions to<br />

problems using your creativity, reasoning, and past experiences along with the<br />

available information and resources. An innovative problem-solver can generate<br />

workable solutions and resolve complaints.<br />

(2) UC Davis, Human Resources: What do Employers Want from Employees? (www.hr.<br />

ucdavis.edu/sdps, 2012).<br />

a. Analytical Thinking – The ability to generate and evaluate a number of alternative<br />

solutions and to make a sound decision regarding a plan of action.<br />

b. Researching – The ability to search for needed data and to use references to obtain<br />

appropriate information.<br />

c. Organizing – The ability to arrange systems and routines to streamline work and<br />

maintain order.<br />

3

4<br />

It is important to note that sources like the above do not stress the need for workers to have extensive<br />

knowledge of particular facts in order to be employable. Actually, nowadays it is rather easy to get<br />

information about almost anything very quicky using the internet. What workers do need instead<br />

is the ability to organize, analyze and integrate the information they find so that they can make viable<br />

proposals to solve problems.<br />

The Information Explosion<br />

In addition to finding a program of study that emphasizes critical thinking and problem solving<br />

skills, students should also consider whether the program will prepare them to deal effectively with<br />

the nature of the modern workplace and the specific problems they will be asked to solve on the job.<br />

First, in today’s workplace, the amount of information that the average corporate worker must digest<br />

is enormous. Consider, for example, just the issue of emails which must be looked at, evaluated, and<br />

often answered before work on a problem can even begin. By 2014, it is projected that the average<br />

number of legitimate corporate emails a worker can expect to receive per day will be 65; the average<br />

number sent will be 39 (Email Statistics Report, 2010, Sara Radicati, The Radicati Group, Inc.,<br />

April, 2010). Adding instant messaging and social networking, it becomes clear that workers must<br />

handle a massive amount of data.<br />

Again, different sources provide different statistics; yet, an undeniable fact is that the internet has<br />

fostered an explosion in the amount of information that is available virtually instantaneously. “Each<br />

year the world produces 800 MB of data per person. It would take approximately 30 feet of shelf<br />

space to hold that amount of information in books. The amount of data produced each year would<br />

fill 37,000 libraries the size of the Library of Congress” (How Much Information Is There? Mark<br />

Shead, 2007; www.productivity501.com). Recent lapses from agencies like Homeland Security, the<br />

CIA, and the FBI have shown alarmingly how easy it is for important communiques to get lost in the<br />

avalanche of data even though such agencies employ experts in surveillance. While national security<br />

is rarely at stake in office emails, the point is clear: to be successful, modern workers need to be able<br />

to digest, sort, organize, and prioritize massive amounts of information efficiently and expertly.<br />

The Problems Facing Today’s Workers<br />

Another factor that students should consider in selecting a program of study involves the nature of<br />

the problems that workers face on a routine basis in the 21st century. Today’s problems are<br />

invariably complex, multifaceted, and subtle. It used to be the case that one could formulate a<br />

problem into a relatively well-defined and stable statement, that one would know when a satisfactory<br />

solution was reached, and that one could clearly evaluate the solution objectively as being good or<br />

bad and right or wrong. That is no longer the case for many problems facing society, government,<br />

and businesses such as the following:

(3) a. Should colleagues be disciplined if they are caught using drugs?<br />

b. How should we deal with crime and violence in our schools?<br />

c. How can we make air travel safe from terrorism?<br />

d. Should people be fired if it is discovered that they are illegal aliens?<br />

e. How can we improve the gas mileage of family cars?<br />

f. Should same sex partners have medical benefits like married couples?<br />

g. How should we improve the language programs in US schools?<br />

As these examples indicate, today’s problems are frequently ill-defined and ambiguous. For<br />

example, in (3a), the question raises other questions like the following: How much drugs, What<br />

kinds of drugs, Are they prescription drugs, Is alcohol included, Is it a first offense, and so on.<br />

Often, today’s problems are associated with strong moral, social, political and professional issues.<br />

For example, it is not possible to talk about preventing violence in schools (3b) or about making air<br />

travel safer (3c) without also considering whether increased surveillance will destroy individual<br />

freedoms or whether certain policies will lead to stereotyping groups on the basis of color or<br />

ethnicity. In some instances such as (3d), there is little consensus about what the problem is, let<br />

alone how to resolve it. Overall, today’s problems are rarely fixed and stable; they involve sets of<br />

complex, interacting issues developing in a dynamic social context. Often, new forms of problems<br />

emerge as a result of trying to understand and solve the original issues (Wicked Problems - Social<br />

Messes, Tom Ritchey, Springer, 2011). For example, proposals about gas mileage (3e) invariably<br />

raise issues about pollution, energy policies, dependence on foreign oil, the dangers of fossil fuels,<br />

the materials from which vehicles are made, and a host of other matters. As a result, in dealing with<br />

today’s problems, there is generally no right answer, and proposed solutions are not good or bad, but<br />

better or worse. To be successful, modern workers must be able to juggle competing proposals to<br />

determine which alternative satisfies the most factors or constituents in the most effective way.<br />

Abstract Thinking<br />

Summarizing, today’s workers need to be good problem solvers and creative thinkers; they need to<br />

be able to organize, analyze, and interpret massive amounts of information and to make proposals<br />

that consider all the stakeholders involved and all the possible consequences that might arise. It is<br />

with those considerations in mind that students should approach the courses they take at university<br />

and the exercises and problems they are asked to complete in those courses. Frequently, students<br />

fail to see the connection between solving a specific problem in a particular course and the problems<br />

they will face outside of the classroom. In fact, there are strategies and procedures that are useful<br />

in attacking all problems, and teaching students how to make such connections is an objective of<br />

education. Students often miss those connections when they focus instead on what appear to them<br />

to be irrelevant facts about useless issues.<br />

The ability to form such connections is vital to success both in college and in the workplace.<br />

Consider the following scenario. A young boy about two years old is walking with his grandfather<br />

in the country near a dirt road when the grandfather says, “Alex, don’t go in the road. You could get<br />

5

6<br />

hurt.” Later that day, the family visits some relatives who live in a suburban subdivision. Alex runs<br />

into the paved street in front of the house to get a ball. The grandfather, very upset, says to Alex, “I<br />

told you not to go into the street.” Alex looks at his grandfather as if to say, “No, you didn’t. You<br />

told me not to go into the road.” At the age of two, children cannot see the connection between a<br />

dirt road in the county and a paved street in a subdivision. Their interpretation of the world is<br />

concrete and literal. It will take a few more years before they are capable of the abstract thinking<br />

required to make such connections.<br />

Abstract thinking is a level of thinking that is removed from concrete, literal, here-and-now<br />

situations. Abstract thinking assesses a variety of specific examples of phenomena and unites them<br />

into a generalized concept that embraces all of the individual instances. Abstract thinkers are able<br />

to put together seemingly disconnected issues and see a larger picture. As an example, consider<br />

another scenario. Two people are applying for a job with an automobile manufacturer. The<br />

interviewer mentions that one of the industry’s most pressing problems is gas mileage; consumers<br />

are concerned about the cost of fuel. The interviewer asks the applicants general questions about<br />

customer satisfaction, options available on new models, electric cars, hybrids, changes needed in the<br />

industry, and so on. During the discussion of options, one applicant volunteers that she is unhappy<br />

with the little “donut” spare tires that come with cars because a person cannot drive very long with<br />

them and must rush to have the flat tire fixed; she believes that cars should come with full spare tires<br />

the way they used to. The other applicant responds by saying that a full spare tire weighs more than<br />

a donut tire. The increased weight will make the car heavier and, therefore, reduce gas mileage.<br />

Who gets the job?<br />

Practice<br />

Students don’t always see the connections between the various exercises that they are assigned to<br />

complete in various courses and the “real world.” But, learning how to solve problems, think<br />

abstractly, analyze data, propose hypotheses, and argue for a particular position – all of the skills<br />

required for today’s workplace – require exactly the kind of practice one gets working on different<br />

exercises in different courses. Practice is essential. Even experienced people practice and train on<br />

a daily basis so they can maintain their expertise and develop professionally. Ballet dancers spend<br />

long hours every day at the barre practicing plies and tendus so they can become proficient. Boxers<br />

train every day; authors write every day; scientists experiment; philosophers ponder; golfers golf.<br />

It’s often said that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery in any skill. Students cannot<br />

expect to become successful thinkers if they don’t have practice solving a variety of different<br />

problems as often as possible. Students generally think that they should be able to solve any problem<br />

in twenty minutes, and, if they can’t, something must be wrong with them or their teachers. That is<br />

incorrect as the above facts about today’s problems clearly indicate. Developing skill in problemsolving<br />

like everything else takes practice. When students don’t see the purpose of taking a<br />

particular course to satisfy a particular general education requirement, they need to try to see the<br />

larger picture. It is exactly that larger picture – the relationship between roads and streets, the

elationship between gas mileage and tire size – that is crucial to adaptability, to flexibility, to<br />

mobility, and to success.<br />

Learning by Doing<br />

Students in the United States generally believe that teachers should supply them with facts,<br />

illustrations and the specific means by which they can successfully complete an assignment. There<br />

is an excellent reason for that belief: teachers in the United States generally supply students with<br />

facts, illustrations and the specific means by which they can successfully complete an assignment.<br />

Unfortunately, the problems that one faces in life and at work do not come with instructions for their<br />

solution. In short, what happens in American classrooms frequently has little bearing on what<br />

happens outside them. When evaluation measures depend on memorization and replication, there<br />

is little motivation for creativity, imagination, and objective thought. Consequently, high school and<br />

college graduates often have great difficulty applying what they have learned in new situations. They<br />

have difficulty with abstract thinking. Complexity often paralyzes them because they have few tools<br />

to break down problems into manageable parts. They have not had enough practice doing so.<br />

Students need to have practice and experience dealing with unknowns, managing problems that have<br />

no clear answers, and evaluating competing approaches to find the best solution for the<br />

circumstances when no single approach is completely satisfactory. As the above discussion on<br />

today’s problems shows, those are the skills that are needed in today’s workplace. A teacher’s<br />

function is not to supply students with the right answers or even with the formula to arrive at the<br />

right answers. Rather, teachers need to act more as guides, helping students figure out how to solve<br />

a problem and discover by themselves the principles that best describe the data under investigation.<br />

In that way, students become better able to cope with new and different problems, which will always<br />

occur. It is counterproductive for students to complain that teachers don’t give them the right<br />

answers or the precise way to find the right answer. After all, teachers will not be following students<br />

around for the rest of their lives pointing out the right answers to problems that arise.<br />

Most students pursue a college degree knowing that it will help them in the job market. They know<br />

that college graduates have more and better job opportunities than people without college degrees.<br />

Furthermore, there is abundant research indicating that “college graduates are healthier, contribute<br />

more to their communities, and raise kids who are better prepared academically” (How Much Is a<br />

College Degree Really Worth, Kim Clark, US News, 2008, usnews.com/education). Having decided<br />

to pursue a college education and chosen a major, an immediate concern for students is finding<br />

courses and programs (concentrations, minors, etc.) which will make them most marketable, that is,<br />

ones which will give them practice in the specific skills employers are looking for. As a result,<br />

students should select classes which will help them become innovative and creative thinkers who<br />

can make proposals and solve problems on their own. In that regard, courses in <strong>linguistic</strong>s are<br />

especially appropriate. All <strong>linguistic</strong>s courses focus on gathering, organizing, and analyzing data,<br />

setting up hypotheses to account for the data, and proposing and defending the most generalized and<br />

7

8<br />

effective solutions. By investigating problems in a variety of languages, students of <strong>linguistic</strong>s get<br />

practice developing just those skills that employers are looking for.<br />

A Linguistic Example: English Syntax<br />

As an illustration, consider two approaches that might be used in teaching some basic facts of<br />

English syntax, which is the study of the way sentences are constructed. This illustration might<br />

appear to be absolutely irrelevant to a student’s life or to the “real world” outside of the classroom,<br />

but we will see that it isn’t. One approach to syntax begins with definitions like those in (4) which<br />

teachers ask their students to memorize.<br />

(4) a. The subject of a verb is the person or thing that performs the action in the verb.<br />

b. The object of a verb is the person or thing that receives the action in the verb.<br />

Given (4), students are then asked to find the subjects and objects in sentences like (5).<br />

(5) The dogs frightened the little girl.<br />

Applying (4) to (5), students identify the dogs as the subject phrase because they are causing the fear,<br />

and the little girl as the object phrase because she is experiencing the fear.<br />

The approach, therefore, seems successful. The students have memorized some formulas, the<br />

definitions in (4), applied them in exercises, and learned a tool that can be reused elsewhere. The<br />

teachers have done their job in supplying the formula for completing the assignment.<br />

The difficulty is that English also has sentences like (6).<br />

(6) The little girl feared the dogs.<br />

In (6), the dogs are still causing the fear and the little girl is still experiencing the fear so it seems,<br />

according to (4), that the dogs is still the subject phrase and the little girl is still the object phrase.<br />

If that is correct, then we cannot say that subjects precede verbs in English and objects follow, which<br />

seems to be the case in most sentences. So something is wrong. Since students do not know how<br />

or why the definitions in (4) were proposed in the first place, they generally have no idea what to do<br />

when the definitions seem to fail as they do in sentences like (6).<br />

Now notice what is going on here at an abstract level. We have some data, which happen to be<br />

sentences in English. We have a hypothesis which describes the data, namely, (4). We get some<br />

further data which the hypothesis can’t handle. Thus, we must revise the hypothesis and look for<br />

another proposal. This is exactly what happens frequently in the workplace. Consider, for example,<br />

another scenario from the auto industry.

Several years ago, Ford Motor Company produced a van called the Mercury Villager. This van<br />

originally only had a sliding door on the passenger side. Marketing analysts at Ford had determined<br />

that parents would not want to have a sliding door on the driver’s side because their children might<br />

get out of the van on the side of traffic. The other major auto manufacturers had vans with sliding<br />

doors on both sides, because their marketing analysts had determined that people would find it too<br />

inconvenient going to one side of the car to deposit items like groceries and then walking to the other<br />

side of the car to get into the driver’s seat. Having sliding doors on both sides of the van was<br />

considered a plus. Ultimately, Ford modified its design and offered a new Villager with sliding<br />

doors on both sides. “A sliding door on the driver’s side of the vehicle [was] the subject of popular<br />

demand from customers” (carpartswholesale.com/cpw/mercury~villager~parts.html). At an abstract<br />

level, this problem has the same characteristics as our grammatical problem. Ford began with data,<br />

namely, its marketing <strong>analysis</strong> of what it seemed parents wanted in a van. Ford then designed a car<br />

accordingly. But further data indicated that the design did not match all the needs of its customers.<br />

So, Ford began to produce a new van which did match the additional customer information.<br />

Returning to our grammatical example, consider now an alternative approach to describing subjects<br />

and objects which begins by looking at the data, that is, good sentences like those in (5), (6), and (7),<br />

as well as bad sentences like those in (8), where the asterisk means that the sentence is<br />

ungrammatical.<br />

(7) a. They frightened her.<br />

b. She feared them.<br />

(8) a. *Them frightened she.<br />

b. *Her feared they.<br />

Given data like the above, it is clear that words like she and they must be distinguished from words<br />

like her and them. All native speakers of English know this fact unconsciously whether or not they<br />

have studied English grammar in school. They know that sentences like (7) are good and those like<br />

(8) are not; so they say (7), not (8), even though they usually cannot explain why. As a result,<br />

distinguishing the two groups of words is a necessity for a speaker of English, not a convention or<br />

a convenience. The distinction is part of the English language; it is not something that teachers of<br />

grammar made up.<br />

Since the two groups of words exist, suppose we give them each a name. Notice that there is nothing<br />

odd about this: we have names for all kinds of groups (cars, animals, food, laws, sports, etc.).<br />

Suppose we call words like she and they “subject pronouns” and words like her and them “object<br />

pronouns.” With these new names, we can now succinctly state the distinction between subject<br />

phrases and object phrases, also a necessity if one wants to be a speaker of English. Consider (9).<br />

(9) a. Subject phrases are specified by subject pronouns (she, they, etc.)<br />

b. Object phrases are specified by object pronouns (her, them, etc.)<br />

9

10<br />

Given (9), students attempt to replace phrases in sentences like (5) and (6) with pronouns. The result<br />

is always sentences like (7), never (8). Therefore, students, like native speakers, immediately know<br />

what the subjects and objects are: if a phrase can be specified by a subject pronoun, then it is the<br />

subject; if it can be specified by an object pronoun, then it is an object. In addition, students learn<br />

that the principles in (9) are motivated by facts about the English language, specifically the<br />

distribution of the two groups of pronouns.<br />

The approach just illustrated gets to the heart of the matter and the result is worth repeating.<br />

Grammatical facts are not the result of convention, whim or convenience. They are a necessity;<br />

indeed, they are a biological necessity. The sentences of every human language are broken up into<br />

phrases like subject and object because the human brain cannot process unstructured material very<br />

well. Try, for example, to recall the numbers in (10) after just one reading.<br />

(10) 1 - 4 - 9 - 2 - 2 - 0 - 0 -1 - 1 - 8 - 1 - 2<br />

Now try to recall the same numbers in (11).<br />

(11) 1492 - 2001 - 1812<br />

The numbers in (11) are much easier to recall and process because they have structure. In a similar<br />

way, the sentences of human languages must be composed of structured units like subject and object.<br />

Unstructured sentences without phrases are incomprehensible to human brains. Just try processing<br />

the last sentence backwards. In short, languages have grammar, because human biology demands<br />

it. Phrases which teachers of grammar arbitrarily call “subject” and “object” would exist even if<br />

there were no teachers around to name them and describe them.<br />

Again, we need to take stock at this point to see what we have done. We began with a relatively<br />

specific matter, namely, how to identify subjects and objects in English sentences. We then<br />

determined the following: first, that subjects and objects are phrases; second, that phrases are<br />

structures; third, that the sentences of all languages have such structures; fourth, that sentence<br />

structure is an essential property of language; and fifth, that the properties of language are<br />

biologically determined. In short, the study of grammar is essentially a branch of biology. The<br />

transition here has been a bit abrupt to be wholly convincing; in the discussion below, the argument<br />

will be justified in further detail. At this point, however, it is possible to understand the<br />

methodology and to see what the overall objective is. Specifically, we are attempting to find the<br />

most generalized and comprehensive way to account for the data before us. At an abstract level, that<br />

is exactly what today’s workers must do on the job.<br />

The two approaches mentioned above have been called deductive and inductive. In the deductive<br />

approach, one begins with the principle (rule, theory, definition, etc.) and tries to apply it to the data.<br />

We began with (4) and applied it to (5). In the inductive approach, one begins with the data and tries<br />

to discover what the principle (rule, theory, definition, etc.) is. We looked at good sentences like (7)<br />

and bad sentences like (8) and then formulated (9).

Since the principles in (9) are objective and explicit, they are verifiable. Testing them with other<br />

data reveals that they are, in fact, more robust than the definitions in (4), which fail in many cases:<br />

(12) a. The stewardess is cooking the meals. She is cooking them.<br />

b. The meals are cooking. They are cooking.<br />

(13) a. The laundress is ironing the shirts. She is ironing them.<br />

b. The shirts iron easily. They iron easily.<br />

(14) a. The waitress tasted the potatoes. She tasted them.<br />

b. The potatoes tasted fine. They tasted fine.<br />

(15) a. The girl broke the windows. She broke them.<br />

b. The windows broke. They broke.<br />

The inductive approach supplies students with an exercise in problem solving, critical thinking, and<br />

objective <strong>analysis</strong>. It has the potential of uncovering important generalizations like the principles<br />

in (9) and of helping students understand that such principles are justifiable and, in fact, inevitable<br />

when they are driven by an empirical investigation of the data. As a result, rather than learning<br />

something by rote, students can develop skills for life-long learning, skills that can help even when<br />

there are no teachers available.<br />

In the above illustration, if students focus on the terms “subject” and “object,” they might conclude<br />

that the exercise is irrelevant to their life in the real world, that knowledge of grammatical terms will<br />

not help them on the job. Of course, that is probably correct: very few promotions depend on<br />

knowledge of grammar. But the criticism misses the point. The above illustration is an exercise in<br />

problem solving, in learning to think abstractly, and in formulating robust hypotheses. The solution<br />

to any problem begins with collecting, sorting, and organizing the data, no matter what the data<br />

involve. That step is followed by attempting to find generalizations and connections to account for<br />

the data, principles that will explain the data. In turn, those principles need to be tested on new data<br />

to see if they are robust. When they fail, alternative solutions need to be tried and retested to see if<br />

they are successful. In the end, one produces the best possible proposal. The people who produce<br />

the best proposals are the ones who advance in their careers.<br />

There is a TV commercial which asks the following question: “How can rice production in India<br />

affect wheat output in the U.S., the shipping industry in Norway, and the rubber industry in South<br />

America?” (T. Rowe Price ad; www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ae5BH5KdcI0) The underlying<br />

message of the commercial is that companies, workers, and people in general must be able to make<br />

such connections, because understanding connections that are important and discovering connections<br />

that no one has noticed before are crucial in finding solutions to problems. It is, therefore, essential<br />

that students make every effort to try to understand how the exercises they are asked to complete in<br />

their courses do, in fact, apply to their lives.<br />

11

12<br />

Initially, many students find an inductive approach frustrating; they would prefer that teachers tell<br />

them what to memorize and then test them on their recall. Rather than trying to understand why one<br />

proposal is better than another, they just want to know which one will be on the next test. But<br />

memorization is not learning, and knowledge is not constant. Further, people do not succeed in a<br />

career just by knowing a lot of existing facts. We discover and uncover new phenomena every day<br />

which require changes in existing explanations, theories, practices, and methods. Education must<br />

emphasize the fact that there often are no right answers, only what we know at any given moment.<br />

The purpose of education is to bring students to the point where they can continue to learn on their<br />

own without teachers to guide them.<br />

In short, good teachers strive to make themselves unnecessary by making their students self-reliant.<br />

If a few courses that students take during their education attain that outcome, then students have a<br />

lasting model for life-long learning and for greater adaptability in the workplace. For that to happen,<br />

students need to be given exercises and problems that are new and different from what they have<br />

practiced before. It is useful to remember that the average workers will have ten different jobs<br />

during their working careers. Memorization of a lot of facts is not going to help students cope with<br />

a fluid and variable job market, one that is evolving so fast that it is difficult to keep up with the<br />

changes. The more practice students have with the greater varieties of problems, the broader their<br />

perspectives become. In turn, this broader experience will help them be more adaptable, more<br />

flexible, and more mobile. Although a diploma by itself will give students an edge in securing<br />

employment, they will fare much better over time if that diploma includes courses that give them the<br />

skills and perspectives they need to be responsive to the dynamic nature of today’s job market.<br />

Another Linguistic Example: English Phonology<br />

Let us consider next another <strong>linguistic</strong> example, this time from phonology, the study of the sounds<br />

of language. Verbs in English come in a variety of tenses such as present tense (walks), past tense<br />

(walked), and future tense (will walk). When people are asked how to form the past tense of regular<br />

English verbs, they generally respond with a reference to written English and say something like,<br />

“Add an ed to the end.” Such a rule cannot be part of the natural grammar of any language.<br />

Children know how to correctly produce the past tense of regular verbs long before they learn to read<br />

and write, let alone spell correctly. Indeed, some adults are illiterate; still, they know how to form<br />

the past tense of regular verbs. Writing is based on convention, and learning to write is optional.<br />

There are hundreds of languages which have never been written down; conversely, there is no natural<br />

human language that exists only in written form. These are facts; they form part of our corpus of data<br />

that must be accounted for. They indicate that no language has any natural grammatical rule based<br />

on writing. Our discussion of English syntax above lead to a hypothesis that the rules of natural<br />

grammar are based on human biology. Language is a product of the human language apparatus,<br />

which includes the brain and the organs of speech and hearing. It is important to investigate whether<br />

this hypothesis can be sustained in other aspects of language like phonology.

Now notice that there are actually three ways to pronounce the past tense of regular English verbs.<br />

First, the past tense is pronounced as the sound [t] in a verb like race (They raced from the house).<br />

Second, it is pronounced as the sound [d] in a verb like raise (They raised their hands) or raze (They<br />

razed the building meaning ‘They demolished the building’). And third, it is pronounced as a<br />

separate syllable with the reduced vowel [] before [d] in a verb like rate (They rated the movies)<br />

or raid (They raided the refrigerator). So, we have the following three possibilities which clearly<br />

show that spelling does not determine the correct form of the past tense:<br />

(16) a. [t] raced and also coped, hiked, laughed, ached, etc.<br />

b. [d] raised, razed and also combed, hugged, loved, aged, etc.<br />

c. [d] rated, raided and also coded, hunted, loaded, aided, etc.<br />

It is also clear from the above examples that the correct past tense for any given regular verb ([t], [d],<br />

or [d]) cannot be random. Young children typically try to change irregular verbs into regular verbs,<br />

saying things like I goed there. Importantly, children make up such forms without ever having heard<br />

them. No matter how inelegant an adult’s speech is, no adult would ever say something like I goed<br />

there yesterday. Further, if go were a regular verb, its past tense would have to be pronounced goed,<br />

and children’s spontaneous production of forms like goed indicates that they know that. All this<br />

indicates clearly that children do not acquire their native language by simply imitating the people<br />

around them; there must be more to language acquisition that imitation.<br />

Second, when speakers coin new verbs, they always make them regular and pick the appropriate past<br />

tense marker from among the three possibilities given in (16). Consider, for example, the verb<br />

material girl in a sentence like Madonna has material girled her way to superstardom. Notice that<br />

the [d] variant in example (16b) is the only possible option. This means that when the verb material<br />

girl was first used, its past tense had to be pronounced with a [d] and not either a [t] or an [d]. It<br />

is worth noting here that people, including children, invent new words all the time and, when they<br />

do, they always make them regular with the expected variations. Consider the following examples:<br />

(17) a. I ketchuped up my French Fries. (A five-year-old child)<br />

b. She two-footed that landing. (A TV commentator on figure skating)<br />

c. We clearanced those dresses. (A department store sales person)<br />

Some new past tense verbs that have recently become common include transitioned, decontented,<br />

googled, texted, friended, etc. The essential fact is that native speakers automatically understand all<br />

these words the first time they hear them.<br />

If the form of regular past tenses is not random and the determining factor is not spelling, then there<br />

is an obvious question: What is it that governs the formation of the past tense of regular verbs? To<br />

answer that question, one must first gather the necessary data to see exactly where each of the three<br />

variants for the past tense occurs. Note that this step is exactly the step one must take on the job<br />

when trying to solve any problem, namely, one must gather and organize the data. Doing so in the<br />

present case yields data like the following (ignore the spelling and listen to the sounds):<br />

13

14<br />

(18) a. [t] occurs in verbs ending in the sounds [p] (hyped), [k] (cracked), [f] (cuffed), [s]<br />

(kissed), etc.<br />

b. [d] occurs in verbs ending in the sounds [b] (robbed), [g] (shrugged), [v] (moved),<br />

[z] (cruised), etc.<br />

c. [d] occurs in verbs ending in the sounds [t] (granted) and [d] (guarded)<br />

Testing and verifying the data in (18) is the next step. One looks at as many different regular verbs<br />

as possible to see if the statements are correct. Such investigation reveals that the statements, in fact,<br />

are correct; however, the statements are no more than a list, and a list does not explain why the<br />

sounds are distributed as they are. In other words, why is [p] in (18a) and not (18b) or (18c)? These<br />

are very important steps in proposing solutions to any problem: one must not only gather, organize,<br />

and verify the data; one must explain why the data fall out the way they do if one is going to put forth<br />

the most robust proposal about the data. Although this is a theoretical example about English<br />

phonology, one can still discuss its effectiveness as a matter of cost. The <strong>analysis</strong> in (18) is not very<br />

cost-effective theoretically because it reveals no generalizations. It is not a very good way to account<br />

for the data because it is merely a list. We need to look for common features among the items in the<br />

list to see why they are in one list and not the other. We need to look for generalizations. To see<br />

what this means in a situation one is more likely to encounter in business, consider the following<br />

example.<br />

In the business world, cost is often a primary consideration. The choice of one car design over<br />

another will often depend on its cost-effectiveness. It is most cost-effective for a manufacturer to<br />

vary only the exterior of various models and to use the same underlying mechanical and electrical<br />

systems, the same chassis, the same engines, etc. If every vehicle in a manufacturer’s fleet is built<br />

in a completely different way from every other vehicle and there are no common features, costs will<br />

increase. Thus, manufacturers look for designs that can be generalized over many different specific<br />

vehicles. It is not an accident that many vehicles look alike.<br />

Similarly, in designing homes in a subdivision, builders will use the same underlying floor plan and<br />

only vary the exterior elevations because that cuts down on costs. Architects will put bathrooms on<br />

the second floor above bathrooms on the first floor rather than on opposite sides of the house because<br />

that design is more cost effective. If you ask the architect why the upstairs bathroom is where it is<br />

and not somewhere else, the architect can give you the reason and that reason probably has to do<br />

with cost.<br />

In designing vehicles and buildings, engineers and architects will look for ways in which they can<br />

utilize as many of the same features as they can in all their products as a cost-saving measure. They<br />

will try to generalize. Of course, the same is true not only in the automobile and construction<br />

industries, but other businesses as well. At an abstract level, that is exactly what we need to do with<br />

the data in (18). We need to look for generalizations. Specifically, we need to determine why the<br />

data in (18) fall out the way they do. What do the members of each group have in common?

Since language is a product of human biology, we can expect that the formation of the past tense is<br />

governed by a specific set of principles which are directly related to the nature of the human vocal<br />

apparatus, the part of human anatomy concerned with producing sounds. That expectation turns out<br />

to be correct. To see this, consider first the verbs race and raise. Notice that the final sound of the<br />

verb race is [s] and the final sound of the verb raise is [z]. The difference between [s] and [z] is<br />

technical. When speakers make the sound [s], the vocal cords, which are located in the throat and<br />

help to produce different sounds, do not vibrate, which means that they do not produce a buzzing<br />

sound. There is no buzzing sound when one says [sssssss], for example. On the other hand, when<br />

speakers make the sound [z], the vocal cords do vibrate and produce a buzzing sound, which can be<br />

heard when one says [zzzzzzz]. Most native speakers do not consciously realize this difference, but<br />

they instinctively know when they should vibrate their vocals cords and when they shouldn’t.<br />

Actually, speakers can feel the difference between the sounds if they place a hand on their throat<br />

when they say [sssssss] and [zzzzzzz].<br />

Now notice that there is no vocal cord vibration in the sound [t], but that there is vocal cord vibration<br />

in the sound [d]. Again, speakers can actually feel the tension in their throat when they make the<br />

sound [d], and the tension is the same when they make the sound [z]. However, there is no similar<br />

tension in saying either [s] or [t]. Linguists call sounds which involve vibration of the vocal cords<br />

“voiced” sounds, and those which do not involve vibration of the vocal cords “voiceless” sounds.<br />

During the production of words, it is natural to put sounds together that have the same features, that<br />

is, put voiced sounds together and voiceless sounds together. There are lots of English words that<br />

end in the sounds [st] (raced, missed, passed, etc.) and lots that end in [zd] (raised, dazed, posed,<br />

etc.). However, there are no English words that end in either the sounds [sd] or the sounds [zt],<br />

because such words would join voiced and voiceless sounds together.<br />

Therefore, as a result of the nature of the vocal apparatus, a verb like race, which ends in [s]<br />

(voiceless), should have a past tense that is pronounced with a [t] (voiceless), and it does. A verb<br />

like raise, which ends in a [z] (voiced), should have a past tense that is pronounced with a [d]<br />

(voiced), and it does. Using the technical terms, part of the rule for forming the past tense of regular<br />

verbs is as follows:<br />

(19) a. The past tense is pronounced [t], which is voiceless, in regular verbs that end in<br />

voiceless sounds (coped [pt], hiked [kt], laughed [ft], raced [st], etc.).<br />

b. The past tense is pronounced [d], which is voiced, in regular verbs that end in voiced<br />

sounds (rubbed [bd], hugged [gd], loved [vd], raised [zd], razed [zd], etc.).<br />

Consider now the third variant in (16), namely, the past tense [d] in verbs like hunted, rated,<br />

handed, raided, etc. Notice that there are no words in English that end in the sounds [tt] or the<br />

sounds [dd]. Be careful not to think of spelling in such cases. A verb like putt in The golfer does not<br />

putt well ends in the sound [t], not the sounds [tt]. There is a good reason for this: English does not<br />

allow double consonants at the end of any word or syllable. So, the variants in (19) can’t apply when<br />

a verb already ends in [t] or [d]. In such cases, English uses the third form [d], making the past<br />

tense a separate pronounceable syllable. The full set of rules is as follows:<br />

15

16<br />

(20) a. The past tense is pronounced [t], which is voiceless, in regular verbs that end in<br />

voiceless sounds (coped [pt], hiked [kt], laughed [ft], raced [st], etc.).<br />

b. The past tense is pronounced [d], which is voiced, in regular verbs that end in voiced<br />

sounds (rubbed [bd], hugged [gd], loved [vd], raised [zd], razed [zd], etc.).<br />

c. The past tense is pronounced [d] in regular verbs that end in a [t] or a [d] (hunted<br />

[td], rated [td], handed [dd], raided [dd], etc.)<br />

Notice that (20) is much more cost-effective theoretically than (18). Whereas (18) is merely a list<br />

of items without any principle, (20) explains clearly why each item is in the list that it is in. It is that<br />

kind of generalized solution that linguists are looking for. It is also the kind of generalized solution<br />

that employers are looking for from their employees.<br />

With generalizations such as those in (20), we can now begin to answer some fundamental questions<br />

regarding the acquisition of such principles by children, namely, how they mange to acquire them<br />

so quickly and why they make the kinds of mistakes they do. It is clear that the rules for forming the<br />

correct past tense of regular verbs are known unconsciously to all native speakers of English,<br />

including toddlers. Because the principles are based on the nature of the human vocal apparatus,<br />

they are natural and can be acquired relatively quickly. Furthermore, the past tense of irregular verbs<br />

– forms like went for the past tense of go – are unpredictable and, in a sense, unnatural. It takes<br />

children a long time to master such forms. That is why three-year-old children say things like He<br />

hurted me, which they have never heard; they haven’t yet realized that hurt is an irregular verb. Note<br />

that, if it were a regular verb, its past tense would have to be hurted, following (20c) and parallel to<br />

other regular past tenses like hunted, hoisted, handed, hoarded, etc.<br />

Given the above discussion, a child exposed to English must only figure out that the English past<br />