Impetus - Europa

Impetus - Europa

Impetus - Europa

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

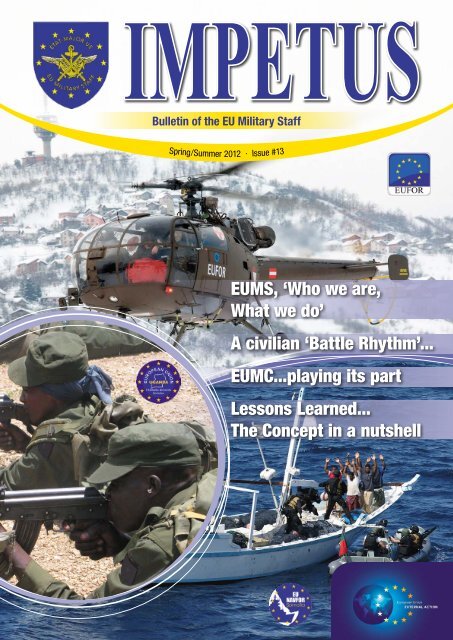

IMPETUS<br />

Bulletin of the EU Military Staff<br />

Spring/Summer 2012 · Issue #13<br />

EUMS, ‘Who we are,<br />

What we do’<br />

A civilian ‘Battle Rhythm’...<br />

EUMC...playing its part<br />

Lessons Learned...<br />

The Concept in a nutshell

PERSPECTIVES<br />

The EUMS: A Team and a Team Player<br />

An interview with Director General EUMS, LtGen Ton van Osch<br />

Lt Gen Ton van Osch,<br />

Director General EU Military Staff.<br />

The EU Military Staff has been part of the<br />

European External Action Service for more than a<br />

year now. What is your first impression?<br />

My first impression is positive, though we should not<br />

underestimate the complexity of weaving together<br />

this innovative Service to deliver real effect for the 27<br />

Member States. But above all I am optimistic for the<br />

future: for the first time we are developing a truly<br />

‘Comprehensive’ approach to crisis management<br />

using all the integral instruments of the EU in concert.<br />

We already see evidence of that improved<br />

‘Comprehensiveness’ in making the EU more efficient<br />

and consequently the military embedded within it; for<br />

example the way the EU has begun to synchronize all<br />

its actions in the Horn of Africa.<br />

What is for you the most important issue?<br />

That there are so many issues. Many of them are<br />

interlinked. There are big issues like the financial crisis<br />

and the huge cuts in Defence budgets, crises in the<br />

southern neighbourhood of the EU, consequences of<br />

climate change, cyber defence, lessons from Libya and<br />

the new strategic focus of the US. Although this<br />

complexity sometimes makes life difficult, nevertheless<br />

one can view such issues as real catalysts for further<br />

development of our Common Security and Defence<br />

Policy. No one can deny that there is an increased need<br />

for the European military to find innovative solutions.<br />

Demand for security is growing and, since budgets are<br />

decreasing, we need to improve cooperation and<br />

2<br />

become more efficient. We do so by implementing an<br />

ever more ‘Comprehensive Approach’ to crisis<br />

management, and by developing new initiatives for<br />

‘Pooling and Sharing’. The EUMS can play an important<br />

role in translating the political intent into concrete action.<br />

Aren’t there also many organizational issues to<br />

be solved?<br />

Certainly! Remember 2011 was the year in which the<br />

EEAS was created. This coincided with a period of a<br />

heightened number of crises. We could not afford to<br />

close the shop, sit back and dream-up plans for the<br />

reorganisation. Reality intervened. We had to learn by<br />

experience on the way. That often is not the best way,<br />

but it was the only way open to us. We all know that<br />

there is a long list of organisational issues to be solved.<br />

But at least, we now have a clear understanding of<br />

what still must be done. Let’s make 2012 the year in<br />

which we solve most of these organisational issues. I’m<br />

grateful to all in the EUMS, the wider EEAS and the<br />

Council Secretariat who work hard to get this done,<br />

knowing it is not an easy job.<br />

Are you satisfied with the role of the EUMS after<br />

the creation of the EEAS?<br />

Yes, but we should not take our role for granted. For<br />

people who are not used to working with the military,<br />

it is not always easy to understand the military approach<br />

to our different tasks. We therefore need to better<br />

explain “who we are and what we do”. Critically, in<br />

everything we do, we must show that we are team<br />

players, thoroughly integrated with our civilian<br />

colleagues within the EEAS. That said, what has not<br />

changed since the creation of the EEAS, is that we also<br />

continue to work under the direction of the EU Military<br />

Committee. There are good reasons for this. For any<br />

military operation, the Chiefs of Defence (represented<br />

through the Military Committee) have to create and<br />

deliver the military capabilities and shoulder the risks.<br />

But they have always understood that the military can<br />

become more effective by applying the levers of power<br />

through a truly civilian and military ‘Comprehensive<br />

Approach’. That is one of the reasons why the EUMS<br />

became part of the EEAS. ‘Comprehensiveness’ is easier<br />

to find at the lower, or ‘softer’, end of the conflict<br />

spectrum. But ‘Comprehensiveness’ does not always<br />

mean the application of ‘soft’ power. I see many<br />

developments in our security environment which<br />

demand that we, as military, also remain capable of<br />

acting quickly with more demanding military capabilities<br />

up to the peace enforcing scale of crisis response. The<br />

strength of the EU is that, uniquely, we have an integral<br />

‘Civ-Mil’ Comprehensive team; the strength of the<br />

military in that construct is that we know how to work<br />

as an integrated Combined and Joint military team as<br />

well. It is great to be part of both teams! n

EU MILITARY STAFF 1<br />

''Who we are, what we do''<br />

We, the EU Military Staff, are the source of military expertise within the EEAS.<br />

3<br />

PERSPECTIVES<br />

We work under the direction of the Military Committee of the Member States Chiefs of Defence<br />

who deliver the military capabilities and under the direct authority of the High Representative<br />

who heads the EEAS and chairs the Foreign Affairs Council (both Foreign Affairs and Defence).<br />

The EEAS coordinates the external actions of the EU. As the EU’s diplomatic service it is also<br />

responsible for the development and execution of the Common Security and Defence Policy.<br />

We are proud to be the military component of this team.<br />

We strengthen the diplomatic leverage of the EU, because together with Member States we<br />

ensure that the EU can act militarily being one of its instruments of power. We assure that our<br />

preparations and actions always fit within the political goals of the EU.<br />

As an integral element of the EU’s Comprehensive Approach - to crisis management, we<br />

coordinate military action. We do so with a focus on operations and the creation of future<br />

military capabilities. For this, we coordinate the military dimensions with the Member State<br />

Defence Staffs, the European Defence Agency, the European Commission, NATO, UN, AU<br />

and strategic partner countries. We do so in full concert with all our partners within the EAS<br />

and specifically the Crisis Management Planning Directorate, the Civilian Planning and<br />

Conduct Capability and our partners for crisis response.<br />

The military can be used across the full spectrum of crisis prevention, response and<br />

management; ranging from support to Humanitarian Assistance, Civil Protection, Security<br />

Sector Reform, stabilization and evacuation of citizens, to more complex military operations<br />

such as peace keeping and peace enforcement.<br />

We have been established to ensure the availability of the military instrument with all its<br />

domains as one integrated military organization. If called upon, we will support our civilian<br />

colleagues with our broad range of expertise, for instance: planning, intelligence, medical,<br />

engineering, infrastructure, transport (land, sea, air), other logistic support, communication,<br />

IT, security, cyber, education, exercises, and lessons learned.<br />

Still, we will not forget that the raison d’être for the military, is the ability to act quickly as one<br />

integrated entity for the broad range of military options, including complex Combined Joint<br />

Operations.<br />

In concert with the EU Military Committee and EEAS-partners, we create the circumstances<br />

in which military can conduct their missions and operations together with their civilian<br />

partners in the field. If security reasons deny others the ability to operate, the military will<br />

stand and act as necessary, accepting the related risks.<br />

This gives us a special responsibility.<br />

1 Established by Council Decision 2001/80/CFSP of 22 January 2001, amended by Council Decision 2008/298/CFSP<br />

of 7 April 2008.

ORGANISATION<br />

EUROPEAN UNION MILITARY STAFF<br />

EU Cell at<br />

SHAPE<br />

DIRECTOR GENERAL<br />

EUMS<br />

CEUMCWG<br />

CEUMC<br />

EU Liaison<br />

UN NY<br />

Chairman European Union Military Committe<br />

Chairman EU Military Committe Working Group<br />

DEPUTY DIRECTOR<br />

GENERAL<br />

LEGAL<br />

ADVISOR<br />

NPLT<br />

EXECUTIVE<br />

OFFICE<br />

CEUMC<br />

SUPPORT<br />

COMMUNICATIONS &<br />

INFORMATION SYSTEMS<br />

LOGISTICS<br />

OPERATIONS<br />

INTELLIGENCE<br />

CONCEPTS &<br />

CAPABILITIES<br />

4<br />

CIS Policy &<br />

Requirements<br />

Logistics<br />

Policy<br />

Military Assessment<br />

& Planning<br />

Intelligence<br />

Policy<br />

Concepts<br />

Information<br />

Technology & Security<br />

Resource<br />

Support<br />

Crisis Response &<br />

Current Operations<br />

Intelligence<br />

Requirements<br />

Force<br />

Capability<br />

Administration<br />

OPSCENTRE &<br />

Watch keeping<br />

Intelligence<br />

Production<br />

Exercises,<br />

Training & Analysis<br />

EUMS

“Dans les affaires diplomatiques, il faut marcher<br />

doucement et avec réserve et ne rien faire de ce<br />

qui n’est pas contenu dans les instructions, parce<br />

qu’il est impossible à un agent isolé de pouvoir<br />

apprécier l’influence de ses opérations sur le<br />

système général. L’Europe forme un système, et<br />

tout ce qu’on fait dans un point rejaillit sur les<br />

autres, il faut donc du concert.” Napoléon (1804)<br />

It could be argued that Napoleon has provided the<br />

first known workable definition of the Comprehensive<br />

Approach (CA). Napoleon noted that when<br />

considering the strategic environment or “système”,<br />

one must not act hastily or without consideration of<br />

the consequences of such an act on the constituent<br />

parts. He deduced that any action must be coordinated<br />

and in concert. In today’s parlance, interrelated and<br />

interdependent constituent parts could include inter<br />

alia: political, diplomatic, security, economic,<br />

development, rule of law and human rights.<br />

From Napoleon’s principle, it is possible to develop<br />

a tentative working definition of the CA<br />

or in French “Approche Globale”:<br />

“L’Approche Globale consiste,<br />

dans une gestion de crise, à<br />

appliquer conjointement des<br />

méthodes d’analyse et de prise de<br />

décision pour faire partager<br />

l’appréhension de l’évolution de la situation par<br />

chaque partie prenante. Celle-ci en déduira les<br />

variations des limites de sa propre liberté d’action, afin<br />

de collaborer à l’harmonisation continue des effets de<br />

ses opérations et de celles des autres acteurs à travers<br />

l’ensemble du système du théâtre stratégique, pour<br />

atteindre l’état final recherché.”<br />

And in English:<br />

“A CA, during crisis management, is defined as the<br />

joint application of analysis and decision making<br />

methods. This builds common situational awareness for<br />

every stakeholder, who will be able to identify their<br />

own specific limitations and variable freedoms of<br />

action. This will facilitate the continuous harmonisation<br />

of their operations’ effects with those of other actors<br />

throughout the whole system of the strategic theatre,<br />

in order to achieve the end state.”<br />

5<br />

CAPABILITIES<br />

Deconflict, Coordinate, Cooperate<br />

and Synchronise Comprehensive<br />

Operations Planning<br />

By Lieutenant Colonel Dave Goulding and Lieutenant Colonel René Renucci, Concepts and<br />

Capability Directorate.<br />

planning is indispensible<br />

Lieutenant Colonel René Renucci (FR) and Lieutenant Colonel<br />

Dave Goulding (IE), Concepts and Capability Directorate.<br />

What makes the EU unique is its possibility to react to<br />

a complex, dynamic, interrelated crisis with a combined,<br />

tailored and inclusive response, using the whole<br />

spectrum of both military and civilian<br />

assets and capabilities. This reaction<br />

is the collective commitment to a<br />

crisis or event. It is comprehensive<br />

in nature and incorporates all<br />

Common Security and Defence<br />

Policy (CSDP) actions. It may extend<br />

from initiation to final conclusion, possibly<br />

over an extended period of time, and draws all<br />

capabilities and expenditure into a continuous<br />

commitment.<br />

“In preparing for battle I have always found that<br />

plans are useless, but planning is indispensible,”<br />

Dwight D. Eisenhower<br />

Comprehensive Planning contributes to the<br />

development and delivery of a coordinated and<br />

coherent response to a crisis on the basis of an allinclusive<br />

analysis of the situation, in particular where<br />

more than one EU instrument is engaged. It includes<br />

identification and consideration of interdependencies,<br />

priorities and sequence of activities and harnesses<br />

resources in an effective and efficient manner, through<br />

a coherent framework that permits review of progress<br />

to be made. This approach applies to all phases of the<br />

planning process for a crisis management operation

CAPABILITIES<br />

conducted under the political control and strategic<br />

direction of the Political and Security Committee under<br />

the responsibility of the Council, and in accordance<br />

with the established procedures for EU crisis<br />

management.<br />

“International systems are not integrated, respond<br />

to disparate incentives, operate on different<br />

timelines and budgets, and are nowhere forged<br />

into common strategy” 1<br />

The interim version of the Comprehensive Operations<br />

Planning Directive 2 (COPD) is the NATO planning<br />

guide for the Strategic level and below.<br />

It is NATO Unclassified - releasable to<br />

PfP/EU/ISAF for the widest possible<br />

distribution within the<br />

international community. The<br />

COPD outlines the procedures and<br />

responsibilities governing the<br />

preparation, approval, assessment,<br />

implementation and review of operations<br />

plans to ensure a common approach to planning. It<br />

supersedes the Allied Command Operations (ACO)<br />

Guidelines for Operational Planning (GOP). COPD is a<br />

set of procedures for operations planning with an<br />

obvious NATO military focus. In order to ensure NATO’s<br />

contribution to the CA, NATO has to reach out and<br />

endeavour to integrate external civilian organisations<br />

(UN, NGOs, State Departments, etc).This is unlike the<br />

EU where the CA can start from within. COPD provides<br />

a common framework for collaborative operations<br />

planning when defining NATOs contribution within a<br />

CA philosophy. It facilitates coordination with other<br />

International Organisations (IOs) and Non Governmental<br />

1 “Recovering from war” - Gaps in early action, a report by the NYU<br />

Center on International Cooperation, (1 July 2008).<br />

2 Interim Version (SHAPE document CPPSPL/4010-79/10, 17<br />

December 2010).<br />

‘Train the Trainer’ Course on NATO Comprehensive Operations Planning (COPD),<br />

27 February - 02 March 2012<br />

Centre to Right, Col Kevin Cotter (uniform, IE), Swedish Instructors - Lt Col Göran Grönberg,<br />

Lt Col Joachim Isacsson,and Lt Col Carsten Persson.<br />

to be perfect is<br />

to change often<br />

6<br />

Organisations (NGOs) to achieve effective and inclusive<br />

planning.<br />

COPD is deliberately detailed to give planners the<br />

necessary tools to fully appreciate all elements of the<br />

most complex crisis and produce high quality operations<br />

plans. The COPD examines a number of issues not<br />

covered previously in the planning process, inter alia:<br />

Civ-mil interaction in a CA, Systems approach to<br />

knowledge development, Operational assessment and<br />

the Process for planning at the Strategic level. In short,<br />

COPD covers all aspects of operations planning at the<br />

Military Strategic and Operational levels of<br />

command. It can also be adapted to<br />

the Component/Tactical level in<br />

order to enhance concurrent<br />

activity. NATO training and<br />

education entities have already<br />

retired the GOP and are now using<br />

COPD. From now on, military<br />

planners will be trained in the COPD.<br />

There is therefore an increasing demand from<br />

Member States (MS) to take the COPD into account.<br />

“To improve is to change; to be perfect is to<br />

change often,” Winston Churchill<br />

The EU’s ability to conduct effective and efficient crisis<br />

management operations depends on the expertise,<br />

currency and capacity of its individual constituent parts.<br />

Therefore it is imperative that the staff are skilled and<br />

knowledgeable regarding existing procedures,<br />

especially key management players who may be<br />

involved in planning real operations.<br />

MILEX 10 and MILEX 11 were exercises that took place<br />

from 16 June to 25 June 2010 and from 16 May to 27<br />

May 2011, respectively. These exercises focused on the<br />

interaction between an EU OHQ and an EU FHQ in an<br />

EU-led military operation without recourse to NATO<br />

common assets and capabilities. The aims of both were<br />

to exercise and evaluate military aspects of EU crisis

management at the military strategic and operational<br />

levels, based on scenarios for an EU-led military<br />

operation.<br />

MILEX 10 Final Exercise Report 3 noted that the current<br />

EU OHQ SOPs are based on the GOP and fail to reflect<br />

the CA aspect at the military strategic level. It<br />

recommends integrating the CA in future EU planning<br />

directives and in the next revision of the EU HQ SOPs 4 .<br />

Likewise the MILEX 11 Final Exercise Report 5 suggests<br />

a review of SOPs and replacement of the GOP with the<br />

COPD - as the standard tool for operations planning.<br />

The report added that GOP based<br />

planning tended to duplicate efforts<br />

on the strategic and operational<br />

levels. In order to solve this issue a<br />

clearer distinction between the<br />

planning responsibilities of the<br />

different levels is required. This<br />

distinction is reflected in the COPD,<br />

leading to a more efficient and effective<br />

planning process.<br />

As a result of the above mentioned reports and being<br />

cognisant of current best practice, a “COPD Task<br />

Group” was established by DGEUMS in January 2012.<br />

The group, led by the Concepts and Capabilities<br />

Directorate, is comprised of representatives from all<br />

EUMS Directorates. The group’s task is to analyse the<br />

COPD through an EU lens, with a view to its use as the<br />

main planning tool for EU operations. The resulting<br />

analysis will also facilitate the revision of EU HQ SOPs.<br />

The planned methodology for the Task Group is divided<br />

into four phases:<br />

3 Final Exercise Report MILEX 10 (13643/10, 20 September 2010)<br />

4 European Union Operational and Force Headquarters Generic<br />

SOPs (SN3649/10, 01 September 2010 and SN 3821/10, 20<br />

September 2010)<br />

5 Final Exercise Report MILEX 11 (11753/11, 20 September 2011)<br />

thought without<br />

learning is perilous<br />

Left to Right, Lt Col García Ortiz (ES), Lt Col François-Régis Dabas (FR) and Lt Col Arturas Purlys (LT).<br />

7<br />

CAPABILITIES<br />

• Phase I (January - 31 May 2012) - analysis of COPD.<br />

• Phase II (01 June - 30 September 2012) - to assist MS<br />

in their preparation and work up for EU Crisis<br />

Management Exercise Multi Layer 2012 (ML 12).<br />

• Phase III (01 October - 26 October 2012) - ML 12.<br />

• Phase IV (27 October - 31 December 2011) - After<br />

Action Review (AAR).<br />

“Learning without thought is labour lost, thought<br />

without learning is perilous,” Confucius<br />

Notwithstanding the fact that all EUMS personnel have<br />

previous training with respect to operational<br />

planning, members of the Task Group<br />

will be required to attend formal<br />

COPD training. This training will<br />

add credibility to the group’s<br />

work, ensure a base line standard<br />

and enhance existing expertise<br />

and knowledge. The “Train the<br />

trainers COPD Course” is scheduled to<br />

be conducted here in the EUMS between 27<br />

February to 02 March 2011. The instruction will be<br />

carried out by members of the Försvarshögskolan<br />

(Swedish National Defence College).<br />

The desired end state for the Task Group is the<br />

production of a “conversion kit” to facilitate planning<br />

of EU operations, while using the NATO COPD as the<br />

main planning tool. ML 12, scheduled to take place<br />

form 01 to 26 October 2012, will provide an opportunity<br />

to validate the work done by the COPD Task Group.<br />

This work, together with the revision of EU SOPs,<br />

should assist the work of future planners in an EU<br />

environment. In conjunction and parallel, a higher level<br />

group under the leadership of Gen Yves de KERMABON<br />

(Retd) is currently revising the CSDP Crisis Management<br />

Procedures. This work will take account of the new<br />

structures post Lisbon and aim to align Civ and Mil<br />

planning processes with a view to compressing the<br />

planning process timelines. n

PARTNERS<br />

Common challenges for the<br />

Armed Forces of the European<br />

Union Member States -<br />

reflections on the state of play<br />

and on the way ahead<br />

By General Håkan Syrén, Chairman of the European Union Military Committee (CEUMC).<br />

Responding to the Lisbon Treaty<br />

Two and a half years have passed since the entry into<br />

force of the Lisbon Treaty in December 2009. It is<br />

appropriate now to assess the achievements and the<br />

present state of play in the development of the military<br />

dimension of the Common Security and Defence Policy<br />

(CSDP). I am focussing on the achievements, challenges<br />

and opportunities ahead rather than on failures and<br />

problems, although, of course, with a readiness to<br />

draw constructive lessons from the past.<br />

We are currently facing an extremely challenging period.<br />

The shifts in the global balance of power, accompanied<br />

by the severe economic and political strains<br />

within the Union itself have made the general<br />

conditions for setting the sails of the<br />

strengthened Security and Defence<br />

Policy within the EU very different<br />

from what was envisaged at its<br />

start. Furthermore, the revolutionary<br />

changes in North Africa<br />

and the Arab world have brought<br />

new and urgent tasks onto the EU agenda.<br />

Our outlook for the CSDP is global, but recent<br />

experience has reminded us that the stability and security<br />

of our own close neighbourhood cannot be taken<br />

for granted.<br />

The pressures on the formation of the EEAS have thus<br />

been very great. On the whole I think that the pressures<br />

have helped us to prioritise and focus our work. Much<br />

remains to be done and the need for strategic and<br />

thoughtful European leadership is greater than ever.<br />

The EUMC is playing its part. It responded proactively<br />

to the challenges raised in the Lisbon Treaty by formulating<br />

a Strategic Plan, focusing on five priorities: Operations,<br />

Comprehensive Approach, Capabilities, Strategic<br />

Partnerships, and last but not least, general support to<br />

the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty. By and large,<br />

those priorities have provided relevant guidance, not<br />

only for the work of the EUMC, but for other parts of<br />

the CSDP structures as well. They have also proved to<br />

EUMC is playing its part<br />

8<br />

Gen Syrén meeting with Officers of the Uganda Peoples<br />

Defence Force (UPDF) during a visit to EUTM Somalia.<br />

be a comprehensive and understandable<br />

framework for presenting what the<br />

EUMC is doing for ministers, parliamentarians<br />

and others, engaged<br />

in the EU security and defence<br />

policy in Member States as well as<br />

in partner countries. The Chiefs of<br />

Defence at their meeting in Brussels in<br />

April 2012 will review the priorities.<br />

EU Operations and Comprehensive Approach<br />

Supporting EU Operations is always a priority. The EU<br />

can be proud of what has been achieved. EUFOR Althea<br />

in Bosnia-Herzegovina, EU NAVFOR Atalanta operating<br />

outside the Horn of Africa and EUTM Somalia in<br />

Uganda, are all evidence of how the EU is today actively<br />

contributing to international security and stability. The<br />

commanders are indeed delivering against their<br />

mandates. However, reflecting on current force<br />

generation, I see very little room for complacency.<br />

Although the volume of the EU military engagement<br />

remains quite limited, I am seriously concerned about<br />

the current lack of willingness of Member States to<br />

commit resources that match politically agreed<br />

ambitions. This affects operations as well as the EU<br />

Battle Groups.

There is now a broad agreement that the Comprehensive<br />

Approach represents the core of the Common Security<br />

and Defence Policy set out in the Lisbon Treaty. This is<br />

where the EU-framework can really bring added value.<br />

It is a very complex field but the EU is steadily and visibly<br />

moving in the right direction. The present widening of<br />

EU engagement in the Horn of Africa acts as a very<br />

concrete catalyst for these efforts. An essential part of<br />

the Comprehensive Approach is about successful<br />

Conflict Prevention and the EUMC is actively working<br />

to develop the military support.<br />

EU NAVFOR Atalanta against piracy at sea is a success<br />

in many ways. It is providing efficient protection for the<br />

World Food Programme and for a large number of<br />

other ships off the coast of the Horn of Africa. It is also<br />

a catalyst for cooperation with a broad range of<br />

partners from all parts of the world. At the same time,<br />

it is clear that the problem can only very temporarily<br />

and partially be solved at sea alone. Also, the costs of<br />

the operation are extremely high. A lasting solution<br />

must build on creating a functioning state, providing a<br />

stable and secure environment on land, and efficiently<br />

eliminating the freedom of action for pirates. The EU<br />

Strategic Framework for the Horn of Africa aims at just<br />

that. In addition to Atalanta, the military parts are there<br />

to support the build-up of Somali security forces and<br />

to assist in future maritime capacity building in the area.<br />

Capability Development<br />

Enhancing European Capabilities is one of the most<br />

urgent tasks for the EUMC. The Armed Forces of EU<br />

Member States are now facing very complex and difficult<br />

planning challenges. Defence budgets are cut in response<br />

to the economic crisis. In parallel, demanding<br />

transformation agendas, high operational wear and tear<br />

and a relentless and costly technological development,<br />

have to be managed. Chiefs of Defence are all aware and<br />

deeply concerned about force generation constraints<br />

and about serious underinvestment in future capabilities.<br />

The recent Libya experience leaves no uncertainty about<br />

the pressing need to remedy existing shortfalls.<br />

The EU and its Member States are clearly in a very<br />

different situation compared to when the European<br />

Security Strategy was agreed in 2003. They are also in<br />

a different situation as to when the CSDP was launched.<br />

Priorities need to be reviewed and adapted. The<br />

Member States´ Armed Forces are rapidly approaching<br />

a point, where individual efforts will not suffice to<br />

sustain essential capabilities. We are all losing out<br />

together. This is happening now in front of our eyes.<br />

We now have to define common capability requirements<br />

that are affordable. We have to find ways to improve<br />

efficiency and to make sure that we are really acquiring<br />

those capabilities that are lacking. We cannot continue<br />

to let traditional national sovereignty concerns dominate<br />

our common defence policy and capability development.<br />

Higher efficiency through closer cooperation<br />

and coordination<br />

The political spotlight is now very much on the potential<br />

for increased efficiency through cooperation. Pooling<br />

9<br />

PARTNERS<br />

Chiefs of Defence of the 27 Member States in Brussesls, 22 November 2011.<br />

and sharing and Smart defence have become buzzwords<br />

that carry a lot of expectations and support at the<br />

highest political levels. It is a political momentum,<br />

which the Chiefs of Defence, individually, as well as<br />

together in the EU and NATO Military Committees, are<br />

supporting and are trying to exploit. We are all aware<br />

of the inefficiencies and duplications of current<br />

individual defence efforts.<br />

It is an illusion however, to believe that we can fix our<br />

fundamental long-term challenges through the<br />

cooperation projects that we are currently discussing.<br />

They represent a good start, but the main long-term<br />

value hopefully will be in raising the political awareness<br />

of the impossibility to continue to treat European<br />

defence as only the sum of the individual efforts by 27<br />

sovereign nation states.<br />

The international military community working within<br />

the EU, as well as within NATO, can contribute to the<br />

full political awareness of the situation. The Military<br />

Committees of the EU, as well as of NATO, supported<br />

by their international staffs, have the possibility to give<br />

a credible voice to their common concerns. Formulating<br />

a new way ahead clearly is a task for the EU and NATO<br />

together. Pooling and sharing in the EU is not competing<br />

with Smart Defence in NATO. The aims are largely the<br />

same. All measures that can be taken to make the<br />

European defence efforts more efficient are equally<br />

essential. The EU framework is obviously most relevant<br />

when defining a more common approach to European<br />

capability building as well as to sustaining a competitive<br />

European defence industrial base.<br />

As we move forward it is obvious that a fresh look at<br />

the European Security Strategy is needed. The strategy<br />

now has to be formulated with clear common<br />

priorities and goals. As has been repeated so many<br />

times, Member States only have one set of forces.<br />

Capability development must be seen in the wider<br />

context, in the EU as well as in NATO. Continuing to<br />

define defence policies in separate national stove<br />

pipes will simply not be able to serve the interests<br />

either of individual Member States or of the Union as<br />

a whole.<br />

My strong desire is therefore, that the EU Member<br />

States will soon be ready to translate largely common<br />

strategic aims into common capability goals in a much<br />

more coordinated planning process. n

COHESION<br />

The EU Military Staff from a<br />

Civilian Perspective<br />

Mr. Adam Gutkind.<br />

By Mr. Adam Gutkind, Administrative Assistant, Executive Office.<br />

Working hand in hand<br />

Civilians make up some 7% of the EU Military Staff<br />

(EUMS). Given the usual three-year turnover for<br />

military personnel posted to the EUMS, this small<br />

civilian “platoon” represents continuity, institutional<br />

memory, and a permanent link to the other EU<br />

institutions, diplomatic missions and international<br />

organisations in Brussels. So, what makes the job<br />

interesting for the civilian staff, and how do they<br />

perceive life alongside their military colleagues?<br />

Intensive interaction and an absence of routine, coupled<br />

with constantly changing military personnel, certainly<br />

make for an interesting scenario. Civilians certainly do<br />

not miss out on the action in the EUMS. Personnel and<br />

situations are changing all the time, and civilian<br />

assistants are ready, willing and able to<br />

provide help and support for their<br />

military colleagues with all the<br />

administrative aspects of daily<br />

working life. Civilians are<br />

ambassadors of the EU<br />

administration par excellence! On<br />

the one hand they are available to<br />

ensure that the often complex and<br />

incomprehensible administrative procedures<br />

are followed, and on the other, they need to show<br />

great flexibility in order to find the most effective<br />

solutions.<br />

First weeks in the new job are often stressful for military<br />

newcomers, especially when it may not have been<br />

possible to arrange a complete handover. In such<br />

situations the EUMS assistant is there with a lifeline to<br />

10<br />

help the newcomer to adapt to his/her new<br />

environment. Even for those military personnel who<br />

might return to the EUMS, in a new appointment at a<br />

later date, the EUMS can still offer surprises and<br />

changes. On the whole, the EUMS is continuously<br />

under transformation. This makes the place anything<br />

but boring! The number of officers remains constant,<br />

but what changes is the workload, IT-tools, structure<br />

and institutional environment. An increasing number<br />

of operations and missions, more players and a new<br />

institutional framework with new procedures, have also<br />

had a great impact on the assistant’s job. They<br />

constantly have to update their knowledge to keep the<br />

machinery alive. Up until 2011, and as part of the<br />

European Council, the EUMS was dealing primarily with<br />

the Military Representatives to the EU Military<br />

Committee and the SG High Representative. With the<br />

move to the EEAS in January 2011, the EUMS has new<br />

interlocutors and cooperation partners; the EEAS<br />

geographical directorates, and EU Delegations, as well<br />

as Directorates General of the European Commission<br />

(DEVCO and ECHO). To adapt to the new configuration<br />

and ensure proper communication and collaboration<br />

are the current challenges of the civilian team.<br />

A military bubble?<br />

ensure proper<br />

communication and<br />

collaboration<br />

It is easy to imagine when joining the EUMS that one<br />

enters a military bubble; mysterious and isolated from<br />

the rest of the EEAS; serious, working under orders and<br />

lacking any sense of humour. Nothing could be further<br />

from the truth. The most exiting element of<br />

working in the EU institutions - second<br />

only to that of the policy making at<br />

EU level of course - is the<br />

multicultural environment which<br />

offers a variety of languages and<br />

different backgrounds of people<br />

from all over the EU. The EUMS<br />

offers an extra ingredient for the<br />

cocktail: a Civilian-Military one. A<br />

civilian soon stops seeing the uniforms, and<br />

starts to recognise individuals who bring a great sense<br />

of humour and commitment to the job. Tolerance and<br />

a readiness to adapt, are prerequisites for both sides.<br />

This is especially the case as EUMS procedures are often<br />

unfamiliar to our military colleagues, whose new<br />

counterparts are civilians, with a different<br />

communication code. To the newcomers, at first sight,<br />

the CSDP Crisis Management Procedures are often a

labyrinth. Also, for the civilians the constant merry-goround<br />

of ranks, names and faces can be overwhelming.<br />

As soon as you get to know everybody…someone<br />

leaves, someone arrives, and off we go again!<br />

An EUMS dialect<br />

Aside from all the official languages of the European<br />

Union, and regardless of whether you arrive in the<br />

EUMS from the Council, the Commission, or any other<br />

European institution, nothing can prepare a civilian for<br />

the acronym-laden, military-driven EUMS dialect. The<br />

first step will be the “Lesson Identified”. Your life would<br />

be made considerably easier if you could manage to<br />

absorb a 114 page heavy “Glossary of Acronyms and<br />

Definitions” (updated every six months). If you have<br />

familiarised yourself with this you will have achieved<br />

your “Lesson Learned”. But even then you will need to<br />

“enhance your cooperation” in order to apply the<br />

“Comprehensive Approach”, developing “strategic<br />

planning” in your daily business. You should not forget<br />

that “pooling and sharing” of information and resources<br />

is vital for the latter. And if you are ready with this, go<br />

on the intranet of the EU Delegations and say “Hello”<br />

to your new colleagues around the globe using their<br />

own EUDEL Glossary. As you can see, it is truly a matter<br />

of “lifelong learning” - to paraphrase the Commission’s<br />

education programme. The civilians can only reply in<br />

their own dialect with ARES, MIPS, SYSPER, SYSLOG,<br />

OASIS and TSAR, and just occasionally we find that we<br />

are all speaking the same language on MARS, SOLAN<br />

and IOLAN networks.<br />

A Civilian “Battle Rhythm”<br />

The civilian “battle rhythm” within the EUMS is<br />

influenced only partially by the opening hours of the<br />

mess! The civilian’s calendar is guided by upcoming<br />

events which are closely linked with military occasions.<br />

Preparation of documents for the EU Military Committee<br />

starts in the morning and goes on late into the evening.<br />

Assistants therefore work overtime according to a duty<br />

roster. This also covers weekends and holiday periods<br />

whenever an EU operation enters its preparation phase.<br />

Sometimes it is a “Friday night fever” rather than the<br />

“short Friday”, known in some spots in Brussels. To<br />

ensure coherence and high standards of work<br />

performance, civilians in the EUMS meet regularly and<br />

discuss administrative issues of common importance.<br />

This is an occasion to become aware of specific aspects<br />

of the work of other colleagues and to be prepared to<br />

take over when necessary.<br />

Stay fit wherever you sit<br />

Hours spent working in front of a computer screen (of<br />

which everyone in EUMS has at least TWO) and long<br />

periods sitting in one place, can be detrimental to work<br />

performance, but EUMS assistants are in a happy<br />

situation. Just across the street they may enjoy the<br />

hospitality of the Belgian Military Academy and, for a<br />

small fee, use their sports facilities. They also have an<br />

opportunity to discover their potential by attending the<br />

11<br />

EUMS Civilian Personnel.<br />

COHESION<br />

annual “EUMS Sport Day”, and to play non-political<br />

games with their bosses.<br />

Time for work - time for play<br />

In order to encourage and support team spirit, the<br />

EUMS regularly organises social events. Those occasions<br />

truly strengthen the ties, not only among the military,<br />

but also with the civilian staff. Every few weeks the<br />

EUMS welcomes both military and civilian newcomers<br />

with a glass of wine, and bids farewell to those who<br />

are leaving. Annually on 9 May, the EU celebrates<br />

Europe Day. Having officers from all EU countries,<br />

EUMS also celebrates the National Days of the Member<br />

States, prepared by the officers from the respective<br />

countries. Once a month the EUMS Social Club gives<br />

all hardworking members an opportunity to drop the<br />

‘mouse’ in the office, catch a glass of beer and meet<br />

colleagues.<br />

City trips across Belgium and surrounding countries also<br />

provide an opportunity to get to know one another<br />

better. The Gala Dinner, organised every autumn for all<br />

EUMS staff, is certainly a glamorous event not to be<br />

missed. It is also possible to meet up and cook with<br />

military colleagues in “civilian” mode, at popular events<br />

such as the annual “Pizza Party”. Coming closer to the<br />

end of the year you will experience a civilian-military<br />

Christmas when miracles really happen. (All social<br />

events are covered by individual members’ fees).<br />

10 years on: emerging market for assistants<br />

With six CSDP military operations and one military<br />

training mission since 2003, the EUMS continues to<br />

offer civilians the opportunity to become an active part<br />

of crisis management and to understand the<br />

mechanisms driving the European Common Security<br />

and Defence Policy. Especially now, the extended<br />

cooperation with new services, gives assistants more<br />

opportunities to learn and to transfer their knowledge.<br />

As long as the EU does not reach its “plateau”, aside<br />

from demanding work, the EUMS will offer its civilians<br />

more and more interesting insights, good memories<br />

and friendships. n

GLOBAL MEMO<br />

EU Missions and Operations<br />

Since 2003, the EU has conducted, or is conducting, 24 missions and operations under<br />

CSDP. 7 are military operations/missions. The remainder are civilian missions, although<br />

in many areas, a high proportion of personnel are also military. Currently, the EU is<br />

undertaking 12 missions and operations under CSDP (3 military and 9 civilian)<br />

Missions/Operations EUROPE AFRICA MIDDLE EAST ASIA<br />

Military<br />

Civilian<br />

CONCORDIA<br />

(Former Yugoslav<br />

Republic of Macedonia)<br />

Mar – Dec 03<br />

EUFOR ALTHEA<br />

(Bosnia i Herzegovina)<br />

Dec 04 –<br />

EUPOL Proxima (FYROM)<br />

Dec 03 – Dec 05<br />

EUPAT (FYROM)<br />

Followed EUPOL Proxima<br />

Dec 05 – Jun 06<br />

EUPM BiH<br />

(Bosnia i Herzegovina)<br />

01 Jan 03 – 31 Dec 11<br />

(01 Jan – 30 Jun 12<br />

under consideration)<br />

EUJUST Themis (Georgia)<br />

Jul 04 – Jul 05<br />

EUPT Kosovo<br />

Apr 06 – 08<br />

EULEX Kosovo<br />

16 Feb 08 – 14 Jun 12<br />

EUMM Georgia<br />

01 Oct 08 – 14 Sep 12<br />

Note: Missions/Operations in bold blue are ongoing.<br />

ARTEMIS<br />

(Ituri province, Congo RDC)<br />

Jun – Sep 03<br />

EUFOR RD Congo<br />

(Congo RDC)<br />

Jun 06 – Nov 06<br />

EUFOR TCHAD/RCA<br />

(Chad-Central African Republic)<br />

Jan 08 – Mar 09<br />

EU NAVFOR ATALANTA<br />

(Coast of Somalia)<br />

Dec 08 –<br />

EUTM Somalia<br />

(Training Mission - Uganda)<br />

Apr 10 – Dec 12<br />

EUSEC RD Congo<br />

(Congo RDC)<br />

Jun 05 –<br />

EUPOL Kinshasa<br />

(Congo RDC)<br />

Apr 05 – Jun 07<br />

EUPOL RD Congo<br />

(Congo RDC)<br />

Jul 07 – 30 Sep 12<br />

EU SSR Guinea-Bissau<br />

Jun 08 – Sep 10<br />

AMIS II Support<br />

(Darfur province, Sudan)<br />

Jul 05 – Dec 07<br />

12<br />

EUPOL-COPPS<br />

(Occupied<br />

Palestinian<br />

Territory)<br />

1 Jan 06 – 30<br />

June 12<br />

EUJUST LEX<br />

(Iraq)<br />

Jul 05 – Jun 12<br />

EUBAM Rafah<br />

(Occupied<br />

Palestinian<br />

Territory)<br />

30 Nov 05 – 30<br />

June 12<br />

AMM<br />

(Aceh province,<br />

Indonesia)<br />

Sept 05 – Dec 06<br />

EUPOL<br />

Afghanistan<br />

(Afghanistan)<br />

15 June 07 –<br />

31 May 13<br />

* as of 01 November<br />

2011

EUROPE CIVILIAN MISSIONS MILITARY MISSIONS<br />

BOSNIA I HERZEGOVINA (BIH)<br />

EUPM<br />

Type: Police mission. EUPM was the first CSDP operation launched<br />

by the EU on 1 January 2003.<br />

Objectives: EUPM seeks to establish effective policing arrangements under<br />

BiH ownership in accordance with best European and<br />

international practice. EUPM aims through mentoring,<br />

monitoring, and advising to establish a sustainable, professional<br />

and multiethnic police service in BiH. For the next six months,<br />

the Mission will continue to support relevant BiH Law<br />

Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) and the wider criminal justice<br />

system in fighting organised crime and corruption, in enhancing<br />

the interaction between police and prosecutors and in fostering<br />

regional and international cooperation.<br />

Mandate: Launched in January 2003, EUPM’s mandate has been<br />

extended five times and will expire 30 June 2012 when there<br />

will be a handover to the EUSR.<br />

Commitment: Authorized strength: 34 international staff and 48 local staff.<br />

Current strength: 34 international and 48 local staff. Nine EU<br />

Member States and two Third States (Turkey and Switzerland)<br />

contribute to the Mission.<br />

The Mission’s HQ is in Sarajevo. The budget is € 5,250M (until<br />

30 June 2012).<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

BOSNIA I HERZEGOVINA (BIH)<br />

EUFOR ALTHEA<br />

BG Stefan Feller (DE) is the Head of Mission.<br />

(Peter Sorensen (DK) is the EUSR* in BiH).<br />

Type: Military EU-led operation.<br />

Objectives: To conduct operations in line with its mandate: to support BiH<br />

efforts to maintain the Safe and Secure Environment (SASE), to<br />

provide military technical support, monitoring and advice in<br />

specific areas to strengthen local ownership and capacities of<br />

relevant BiH institutions and support AFBiH capacity - building<br />

and military training.<br />

Mandate: In December 2004, EUFOR took over responsibility to maintain<br />

a safe and secure environment in the BiH from NATO-led<br />

mission SFOR, under chapter 7 of charter of the United Nations.<br />

Commitment: About 1300 troops from 21 EU Member States and 5 Third<br />

Contributing States. They are backed up by over-the-horizon<br />

reserves. EUFOR was successfully reconfigured during 2007<br />

and remains ready to respond to possible security challenges.<br />

The common costs (€19M) are paid through contributions by<br />

Member States to the financial mechanism Athena.<br />

Command: The operation is conducted under Berlin+ arrangements, where<br />

NATO SHAPE is a Operational HQ and DSACEUR Gen Sir<br />

Richard Shirreff (NATO) is appointed as the Operation<br />

Commander.<br />

Major General Bernhard Bair (AT) is the COM EUFOR.<br />

13<br />

GEORGIA<br />

EUMM Georgia<br />

Type: EU Monitoring Mission under CSDP framework.<br />

Objectives: EUMM Georgia is monitoring the implementation of the<br />

ceasefire agreements of 12 August and 8 September 2008,<br />

brokered by the EU following the August 2008 armed conflict<br />

between Russian and Georgia. The Mission was launched on 1<br />

October 2008, with four mandated tasks:<br />

Stabilisation: monitoring and analysing the situation pertaining<br />

to the stabilisation process, centred on full compliance of the<br />

agreements of 12 August and 8 September, 2008.<br />

Normalisation: monitoring and analysing the situation with<br />

regard to governance, rule of law, security, public order as well<br />

as the security of infrastructure and the return of internally<br />

displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees.<br />

Confidence building: contributing to the reduction of tensions<br />

through liaison and facilitation of contacts between parties and<br />

other confidence-building measures.<br />

Information: contributing to informing European Policy making.<br />

Mandate: The mission was launched on 1 October 2008. Mandate has<br />

been extended until 14 September 2012.<br />

Commitment: Authorized strength: 333 international staff. Current strength:<br />

284 international staff, including three Brussels Support<br />

Element and around 110 local staff.<br />

The Mission’s HQ is in Tbilisi with three Regional Field Offices in<br />

Mtskheta, Gori and Zugdidi. The budget is €23.9 M (until 14<br />

Sept. 2012).<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

KOSOVO<br />

EULEX KOSOVO<br />

Andrzej Tyszkiewicz (PL) is the Head of Mission.<br />

(Philippe Lefort (FR) is the EUSR* for the South Caucuses and<br />

the crisis in Georgia).<br />

Type: The EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX) is the largest<br />

civilian mission launched under the CSDP.<br />

Objectives: EULEX Kosovo’s mandate is to monitor, mentor and advise local<br />

authorities with regard to police, justice and customs, while<br />

retaining executive responsibilities in specific areas of<br />

competence (organized crime, war crimes, inter-ethnic crime,<br />

public order as second security responder, etc.).<br />

Mandate: EULEX KOSOVO was launched on 16 February 2008. Mandate<br />

extended until 14 June 2012.<br />

Commitment: Authorised strength: 1950 internationals. Currently circa 1650<br />

internationals in Kosovo, five Brussels Support Element and<br />

circa 1200 local staff. All EU Member States and five Third<br />

States (Croatia, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey and USA)<br />

contribute to the Mission.<br />

The Mission’s HQ is in Pristina. The budget is €75 M (15 Dec<br />

2011 - 14 June 2012).<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

GLOBAL MEMO<br />

Xavier Bout de Marnhac (FR) is the Head of Mission as of 15<br />

October 2010.<br />

(Samuel Zbogar (SI) is the EUSR and Head of EU Office in<br />

Kosovo.)

AFRICA<br />

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO<br />

EUSEC RD Congo<br />

Type: Support mission in the field of Security Sector Reform.<br />

Objectives: Provide advice and assistance for the reform of the Congolese<br />

Armed forces (FARDC). Focus on restructuring and<br />

reconstructing the armed forces.<br />

Commitment: The authorized mission strength is 50. Civilian and military<br />

expertises include defence, security, human resources,<br />

Education and training, logistic, administrative and financial<br />

regulations. The HQ is located in Kinshasa with 3 detachments<br />

deployed in the eastern military regions: Goma, Bukavu and<br />

Lubumbashi.<br />

The mission budget is €16 M since June 2005 plus a further<br />

€12.6 M for 2010-2011.<br />

Mandate: EUSEC RD Congo was launched in June 2005. The mandate of<br />

the mission has been extended yearly until 30 September 2012.<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

GLOBAL MEMO<br />

SOMALIA<br />

On 8 October 2010, General Antonio MARTINS (PT) was<br />

appointed by the PSC as Head of Mission.<br />

EU NAVFOR Somalia (Operation “Atalanta”)<br />

Type: Anti-piracy maritime operation.<br />

First EU maritime operation, conducted in the framework of the<br />

CSDP.<br />

Objectives: In support of UN Security Council Resolutions calling for active<br />

participation in the fight against piracy. The areas of<br />

intervention are the Gulf of Aden and the Indian ocean off the<br />

Somali Coast. The mission includes:<br />

– Protection of vessels of the World Food Programme (WFP)<br />

delivering food aid to displaced persons in Somalia; the<br />

protection of African Union Mission on (AMISOM) shipping;<br />

– Deterrence, prevention and repression of acts of piracy and<br />

armed robbery off the Somali coast.;<br />

Protection of vulnerable shipping off the Somali coast on a case<br />

by case basis;<br />

– In addition, ATALANTA shall also contribute to the monitoring<br />

of fishing activities of the coast of Somalia.<br />

Commitment: Initial Operational Capability was reached on 13 December<br />

2008. EU NAVFOR typically consists of 4 to 8 surface combat<br />

vessels, 1 to 2 auxiliary ships and 2 to 4 Maritime Patrol<br />

Aircraft. Including land based personnel EU NAVFOR consists of<br />

around 2,000 military personnel. Annual common costs of the<br />

operation are €8M.<br />

The EU Operational Headquarters is located at Northwood (UK).<br />

Mandate: Launched on 8 December 2008 and initially planned for a<br />

period of 12 months, Op Atalanta has been extended until<br />

December 2014.<br />

Command: Rear Admiral Potts (UK) is the EU Operation Commander.<br />

Capt (N) Manso Revilla (ES) is the Force Commander of<br />

EUNAVFOR (Dec 2012 - )<br />

14<br />

CIVILIAN MISSIONS MILITARY MISSIONS<br />

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO<br />

EUPOL RD CONGO (ex- EUPOL Kinshasa)<br />

Type: Police mission with a justice interface.<br />

Objectives: Support the Security Sector Reform in the field of policing and<br />

its interface with the justice system.<br />

Commitment: Authorized strength: 50 international staff. Current strength: 42<br />

international and 19 local staff. Eight EU Member States<br />

contribute to the Mission. Expertises include police, judiciary,<br />

rule of law, human rights and gender balance specialists.<br />

The Mission’s HQ is in Kinshasa and an ‘East antenna’ is<br />

deployed in Goma (North Kivu). The budget is €7.2 M (Oct<br />

2011 - Sept 2012).<br />

Mandate: EUPOL RD Congo builds on EUPOL Kinshasa (2005-2007, the<br />

first EU mission in Africa). Launched on 1 July 2007. Mandate<br />

has been extended, with successive modifications, until 30<br />

September 2012.<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

SOMALIA<br />

Chief Superintendent Jean-Paul Rikir (BE) is the Head of<br />

Mission.<br />

(The post has been suppressed. Mr Gary Quince was appointed<br />

EUSR for the African Union (AU) on 1 November 2011.)<br />

EUTM Somalia<br />

Type: Military mission to contribute to the training of Somali<br />

Security Forces.<br />

Objectives: Based on the already existing training of the Somali Security<br />

Forces, conducted by the Ugandan Defence Forces (UPDF), the<br />

EU mission compliments the training programmes by providing<br />

specific military training to Somali recruits and appropriate<br />

modular and specialized training for officers and noncommissioned<br />

officers up to and including platoon level. On 28<br />

July 2011, by Council Decision, the mission has received a<br />

re-focused mandate and will concentrate in two six months<br />

training periods on the training of Commanders, specialists and<br />

staff personnel up to company level and, in addition, to conduct<br />

a specific ‘train the trainers programme’ for Somali trainers with<br />

a view to transfer basic training up to platoon level back to<br />

Somalia.<br />

Up to date EUTM Somalia has contributed to the training of<br />

1800 Somali soldiers during the first mandate.<br />

Commitment: Full Operational Capability (FOC) was achieved on 01 May<br />

2010. The Revised Mission Plan was approved by the PSC on<br />

27 September 2011. The amended mission comprises 125<br />

personnel and the estimated financial reference amount for the<br />

common costs of the operation is €4,8M. The training is being<br />

conducted in Bihanga Training Camp in Uganda. The Mission<br />

HQ is situated in Kampala.<br />

Mandate: Launched on 07 April 2010 and initially planned for two 6<br />

months training periods after FOC. On 28 July, by Council<br />

Decision, the amendment and extension of the Council Decision<br />

2010/96/CFSP was authorized and EUTM Somalia will continue<br />

until December 2012.<br />

Command: Colonel Michael BEARY has been appointed EU Mission<br />

Commander with effect from 9 August 2011. The mission<br />

commander exercises the functions of EU Operation<br />

Commander and EU Force Commander.

MIDDLE-EAST ASIA<br />

PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES<br />

EUPOL COPPS<br />

Type: Police and Rule-of-Law mission.<br />

Objectives: To contribute to the establishment of sustainable and effective<br />

policing arrangements under Palestinian ownership in<br />

accordance with best international standards, in cooperation<br />

with the Community’s institution building programmes as well<br />

as other international efforts in the wider context of Security<br />

Sector including Criminal Justice Reform.<br />

Commitment: Authorized strength: 70 international staff. Current strength: 52<br />

international (most of them police experts, judges and<br />

prosecutors) and 39 local staff. 17 EU Member States and one<br />

Third State (Canada) contributes to the Mission.<br />

The Mission’s HQ is in Ramallah. The budget is €4,75 M (until<br />

30 June 2012).<br />

Mandate: Launched on 1 January 2006 and current mandate runs until<br />

30 June 2012.<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

IRAQ<br />

EUJUST LEX<br />

Commissioner Henrik Malmquist (SE) is the Head of Mission.<br />

Type: Integrated Rule of Law Mission. EUJUST LEX-Iraq is the<br />

first EU Integrated Rule of Law Mission.<br />

Objectives: Address the needs in the Iraqi criminal justice system through<br />

the provision of training for high and mid level officials in senior<br />

management and criminal investigation, as well as through<br />

strategic mentoring and advising. This training shall aim to<br />

improve the capacity, coordination and collaboration of the<br />

different components of the Iraqi criminal justice system.<br />

The training activities and work experience secondments are<br />

taking place in Iraq and in the EU with ethnical and<br />

geographical balance.<br />

Commitment: Authorized strength: 69 international staff in Baghdad, Basra,<br />

Erbil and Brussels. Current strength: Head of Mission plus 46<br />

internationals. 16 EU Member States contribute to the Mission.<br />

The budget is € 27,25M (July 2011 - June 2012).<br />

Mandate: Launched in March 2005. Extended until 30 June 2012.<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

Mr. László HUSZÁR (HU) is the Head of Mission.<br />

15<br />

OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES<br />

EU BAM RAFAH<br />

Type: Border Control Assistance and Monitoring mission.<br />

Objectives: To provide a third party presence at the Rafah Crossing Point in<br />

order to contribute to the opening of the crossing point and to<br />

build confidence between the Government of Israel and the<br />

Palestinian Authority, in co-operation with the European Union’s<br />

institution building efforts.<br />

Commitment: Authorised strength: 13 internationals. Current strength: Nine<br />

international and eight local staff. Seven EU Member States<br />

contribute to the Mission. The Mission’s HQ is located in<br />

Ashkelon, Israel. The budget is €1 M (until 30 June 2012).<br />

Mandate: Operational phase began on 25 November 2005. Current<br />

Mandate runs until 30 June 2012. Since June 2007, operations<br />

have been suspended but the Mission has maintained its full<br />

operational capability and remained on standby, ready to<br />

re-engage and awaiting a political solution.<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

AFGHANISTAN<br />

EUPOL Afghanistan<br />

Alain Faugeras (FR) is Head of Mission.<br />

Type: Police Mission with linkages into wider Rule of Law.<br />

Objectives: Support the Afghan Government to move towards a civilian<br />

police system grounded in the rule of law through policy-level<br />

reform of the Ministry of Interior; training and capacity-building<br />

to support Afghan police leadership; development of specialised<br />

civilian policing skills, developing a efficient investigations and<br />

mutual cooperation between police and judiciary.<br />

Commitment: Authorized strength: 400 international staff (mainly police, law<br />

enforcement and justice experts). Current strength: 346<br />

internationals in Afghanistan, four in the Brussels Support<br />

Element and 209 local staff. 23 EU Member States and four<br />

Third States (Canada, Croatia, New Zealand and Norway)<br />

contribute to the Mission. Staff is deployed in Kabul and PRTs).<br />

The Mission’s HQ is in Kabul and it operates in 12 provinces<br />

(located in Provincial Reconstruction Teams. -The budget is<br />

€60.5 M (Aug 2011 - July 2012).<br />

Mandate: Launched on 15 June 2007. Extended until 31 May 2013.<br />

Head of<br />

Mission:<br />

GLOBAL MEMO<br />

MILITARY MISSIONS<br />

CIVILIAN MISSIONS<br />

BG Jukka Savolainen (FI) is Head of Mission.<br />

(Vygaudas Ušackas (LT) is the EUSR* for Afghanistan).<br />

NOTE: European Union Special Representatives (EUSRs) and Personal Representatives* are mentioned for info only: they are not in any chain of command.<br />

Hansjoerg Haber (DE) is the Civilian Operations Commander for all civilian CSDP missions; his Deputy is Gilles Janvier (FR). Heads of Mission exercise<br />

command at operational level.

FORCE POLICY<br />

The Use of Force and EU-led<br />

Military Operations<br />

By Lt Col Neville Galea Roberts (MT), formerly EUMS Operations Directorate.<br />

Lt Col Neville Galea Robers (MT), formerly EUMS Operations Directorate.<br />

The term ‘use of force’ has a number of different<br />

meanings. It refers to the rules under international<br />

law which permit States to resort to the use of<br />

force under certain conditions. It also refers to the use<br />

of force by individual personnel and units of the armed<br />

forces during operations. The link between ‘use of force’<br />

as a conditional concession to States, and ‘use of force’<br />

on operations, is that the former sets important elements<br />

of the legal basis and framework, within which the<br />

boundaries of operational use of force must be kept.<br />

‘Use of force’ is also one distinct area of Operational Law,<br />

which, as a result of the above relationship, is heavily<br />

influenced by the legal basis and mandate.<br />

With the one exception of self-defence, for which a<br />

universal and inherent right exists to take action in an<br />

expeditious way, deliberately planned use of force by<br />

the military normally follows a series of principled<br />

political decisions that allocate and authorise certain<br />

military capabilities to deliver force in a legal manner<br />

across agreed timelines and spatial confines.<br />

Use of Force in Self-defence<br />

The use of force in self-defence is a right which is rooted<br />

in natural law 1 and the development of national law,<br />

1 Natural law or lex naturalis is a code of rules prescribed by nature.<br />

One such natural right, or ius naturale, is the right to self-defence.<br />

The right and notion of self-defence are also encapsulated and<br />

promoted in contrasting works of political philosophy. E.g. Thomas<br />

Hobbes (Leviathan, 1651) and John Locke (An Essay Concerning<br />

the True Original, Extent and End of Civil Government, 1689) both<br />

profess the natural right to self-defence, albeit in a different way.<br />

16<br />

with each State providing its citizens, including its service<br />

personnel, precise legal limits to their possibility to<br />

protect themselves, and in some cases, other designated<br />

persons and property. Since the EU has no single, agreed<br />

notion or legal definition of self-defence, any EU concept<br />

on the use of force by the military must be able to<br />

successfully accommodate and reflect the nuances<br />

introduced by the legislation of 27 Member States,<br />

whilst ensuring that adequate and homogenous selfdefence<br />

is deliverable on operations. This is an important<br />

consideration when contemplating and planning Force<br />

Protection, and an issue that Force Commanders and<br />

Component Commanders operating in a multinational<br />

configuration need to be aware of, and to tackle. In<br />

truth, the challenge of reflecting national law in such<br />

matters is somewhat offset by two elements. Firstly, the<br />

fact that, in the context of the military, when a situation<br />

so requires, weapons are routinely available for the<br />

purpose of legitimate self-defence. 2 This should imply<br />

that Member States’ authorisations regarding the scope<br />

for individual self-defence of their armed forces<br />

personnel are not drastically different. 3 This aspect of<br />

‘available capability’ is also important since self-defence<br />

is only achievable to the extent of the means available<br />

to provide it. A second source of mitigation to Member<br />

States’ differentiated legal understandings of selfdefence<br />

is the availability to the Commander of specific<br />

Rules of Engagement (ROE) that may cover the gap<br />

between various national legislations.<br />

Rules of Engagement<br />

For those States whose legal definition of self-defence<br />

is limited, the inclusion of specific ROE allow the<br />

Commander the possibility to activate a common level<br />

of individual and corporate self-defence. However, in<br />

general, the function of ROE is to extend the limits of<br />

use of force beyond the restrictive concept of selfdefence.<br />

Although ROE obviously reflect any potential<br />

needs for lethal or less-than-lethal force, it must be<br />

emphasised that ROE are also created for other, nonlethal<br />

actions, not involving the use of weapons, but<br />

2 In contrast, self-defence in an EU civilian context is far more<br />

difficult to streamline, or approximate, since the ability to defend<br />

is largely conditioned by the legal possibilities to bear, store and<br />

use arms, something which varies considerably from one Member<br />

State to another.<br />

3 In practice, however, some differences persist, especially<br />

concerning the question whether the different legislation of<br />

Member States allows for use of force to protect Mission-essential<br />

property, and foreign colleagues of the same Force and, if so, to<br />

what extent.

that could be perceived as hostile. So ROE are not<br />

synonymous solely with the use of kinetic and deadly<br />

force! Through various formal messages, and based on<br />

a compendium of options which is periodically reviewed,<br />

ROE are requested by an Operation Commander,<br />

authorised by the political strategic level and finally<br />

implemented in their authorised form by subordinate<br />

commanders at the operational and tactical levels.<br />

Political Control of the Use of Force<br />

Besides the broader parameters for the potential use<br />

of force which are preconfigured in the mandate,<br />

political approval of the force that may actually be used<br />

by the armed forces hinges on the ability of an<br />

appointed Commander to justify – often in advance –<br />

his or her concept for the application of force on the<br />

basis of the fundamental principles of necessity,<br />

proportionality and minimum force, as they relate to<br />

specific conditions expected in a particular operation.<br />

This element of the military convincing the politicians,<br />

and vice versa, if appropriately handled, provides<br />

healthy checks and balances. Ultimately, though, ‘force’<br />

must be considered as one possible enabler of<br />

previously-defined national, multinational and/or<br />

organisational political interests, and the threat and use<br />

of such force must correspond to the respective public’s<br />

overall will on such matters.<br />

On a national level, use of force policy<br />

for the military must be consistent<br />

with a State’s obligations under<br />

international law, and is also<br />

conditioned by applicable national<br />

law. Such policy must continuously<br />

reflect any relevant shifts in the<br />

political posture of government,<br />

whilst taking into account any State<br />

consent to be bound by new provisions of<br />

international treaties, customary law interpretations,<br />

decisions of particular courts, and relevant eminent<br />

views.<br />

Within a multinational context, things obviously<br />

become somewhat more complicated in what becomes<br />

an aggregate of national positions. Multinational use<br />

of force policy and plans must therefore accommodate<br />

to a high degree the political wills and legal requirements<br />

of all participating States, whether in coalition, or<br />

acting as an organisation. The limits or bounds of<br />

permissible use of such force therefore require much<br />

crafting and often contain an element or two of<br />

otherwise unwanted compromise. Often, strong<br />

political strategic cohesion, national caveats, and a<br />

sense of shared urgency, can jointly resolve differences<br />

concerning the operational use of force.<br />

EU-led Military Operations<br />

With the widespread increase in foreign deployments<br />

in the post-Cold War 1990s, military forces were<br />

required to adapt and expand their thinking on use of<br />

force to allow for new, and often dynamic, situations.<br />

With the important territorial defence scenario sinking<br />

somewhat into the background, the increased use of<br />

the military in peace support operations and non-<br />

consistant with a<br />

State’s obligations<br />

17<br />

FORCE POLICY<br />

defence taskings, and the strategic tendency to think<br />

in terms of combined and joint frameworks, have<br />

invariably impacted use of force theories and concepts<br />

at all levels. In a sense, the EU did not really fully<br />

experience this shift since ESDP, and now CSDP, military<br />

operations, were born in this environment, and have<br />

consistently been geared towards collective security<br />

activities conducted outside EU territory in a new era. 4<br />

The Council, which authorises the ROE, and the Political<br />

and Security Committee, which provides political<br />

guidance and strategic direction under the authority of<br />

the Council and the High Representative for the<br />

Common Foreign and Security Policy, are invested<br />

through the Treaty on European Union with the<br />

responsibility to oversee EU-led Military Operations. In<br />

conjunction with the European External Action Service,<br />

they play important roles in defining and directing to<br />

what extent force plays a part.<br />

Since the operationalisation of the ESDP in 2003, the<br />

Use of Force Concept has provided the structure for<br />

formulating operation-specific plans for use of force.<br />

The document, which was last revised during 2009,<br />

must accommodate and reflect the various permutations<br />

available to the EU, including operations having<br />

recourse to NATO common assets and capabilities, and<br />

those of EU Battlegroups. With force still needed as a<br />

top-drawer solution at times, it is<br />

understandable that the Use of Force<br />

Concept remains a key part of the<br />

overall doctrine guiding EU-led<br />

Military Operations.<br />

The EU has launched six military<br />

operations and one military training<br />

mission, and in addition, stood ready<br />

to assist in humanitarian operations in<br />

Libya should UN OCHA request assistance.<br />

Whether it is counter-piracy naval operations off<br />