Thursday 12 May programme - London Symphony Orchestra

Thursday 12 May programme - London Symphony Orchestra

Thursday 12 May programme - London Symphony Orchestra

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

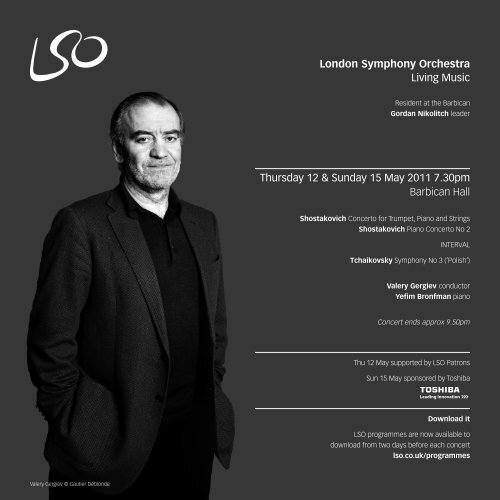

Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

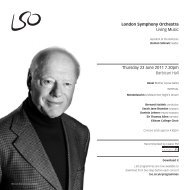

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

Resident at the Barbican<br />

Gordan Nikolitch leader<br />

<strong>Thursday</strong> <strong>12</strong> & Sunday 15 <strong>May</strong> 2011 7.30pm<br />

Barbican Hall<br />

Shostakovich Concerto for Trumpet, Piano and Strings<br />

Shostakovich Piano Concerto No 2<br />

INTERVAL<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 3 (‘Polish’)<br />

Valery Gergiev conductor<br />

Yefim Bronfman piano<br />

Concert ends approx 9.50pm<br />

Thu <strong>12</strong> <strong>May</strong> supported by LSO Patrons<br />

Sun 15 <strong>May</strong> sponsored by Toshiba<br />

Download it<br />

LSO <strong>programme</strong>s are now available to<br />

download from two days before each concert<br />

lso.co.uk/<strong>programme</strong>s

Welcome News<br />

Welcome to these two concerts which see the third instalment of<br />

Principal Conductor Valery Gergiev’s Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> Cycle.<br />

Yefim Bronfman makes a welcome return to the LSO performing<br />

as soloist tonight. Later in the month, the LSO and Gergiev take<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 3 on tour in Switzerland to Bern, Geneva,<br />

Lugano, Zürich and Lucerne.<br />

I would like to take the opportunity to thank LSO Patrons for<br />

supporting the concert on <strong>12</strong> <strong>May</strong> and for the continued support<br />

from Toshiba who sponsors 15 <strong>May</strong>.<br />

I hope you enjoy the performance tonight and that you can join us<br />

for our next concert on 26 <strong>May</strong> when Sir Colin Davis continues his<br />

highly acclaimed cycle of Nielsen symphonies, joined by Mitsuko<br />

Uchida for the start of the LSO’s Beethoven Piano Concerto series.<br />

Kathryn McDowell<br />

LSO Managing Director<br />

2 Welcome & News<br />

LSO retired and past players’ reunion<br />

Since the LSO’s centenary in 2004 it has become an annual tradition<br />

to invite retired and past players to attend a Barbican concert.<br />

On 15 <strong>May</strong> we are joined by many former members of the <strong>Orchestra</strong> –<br />

a warm welcome back to all.<br />

Into the LSO: for our teenage audiences<br />

If you’re aged 13–18, or you know someone who is, join our free<br />

‘Into the LSO’ teens scheme and take advantage of cheap tickets,<br />

pre-concert events and exclusive chances to meet the LSO players.<br />

Before the concert on 15 <strong>May</strong> there will be a free talk introducing<br />

the evening’s music and you’ll also find some extra <strong>programme</strong><br />

notes for a quirky angle on the music!<br />

Find out more at lso.co.uk/intothelso<br />

Support the LSO’s Annual Fund<br />

The LSO’s Annual Fund gives you the opportunity to donate whatever<br />

you are able. Your gift will ensure that the LSO continues to make the<br />

finest music available to the greatest number of people. Every gift is<br />

important, however small.<br />

You can donate online and read stories of how the LSO has made a<br />

difference at lso.co.uk/annualfund<br />

Or you can donate £5 by text message now<br />

Text LSO DONATE5 to 60<strong>12</strong>3<br />

LSO Live wins double award at BBC Music Magazine Awards<br />

We are delighted to have won the BBC Music Magazine Disc of the<br />

Year Award for our LSO Live recording of Prokofiev’s Romeo and<br />

Juliet, as well as winning the Award in the orchestral category. The<br />

Disc of the Year Award was presented to the LSO by the composer’s<br />

grandson, Gabriel Prokofiev, at a ceremony at Kings Place (Gabriel<br />

is also appearing at LSO St Luke’s on 17 <strong>May</strong>). Pick up the <strong>May</strong> issue<br />

of BBC Music Magazine for a full feature on the award-winning<br />

recordings and an interview with the man at the helm, Valery Gergiev.<br />

Kathryn McDowell © Camilla Panufnik

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)<br />

Concerto for Trumpet, Piano and Strings Op 35 (1933)<br />

1 Allegretto<br />

2 Moderato<br />

3 Lento<br />

4 Allegro con brio<br />

Yefim Bronfman piano<br />

Philip Cobb trumpet<br />

As a young man Shostakovich had ambitions to become a composer-<br />

pianist in the mould of Rachmaninov or Prokofiev, and by his early<br />

twenties he had gained a notable position in Russia as a solo pianist.<br />

In 1927 he had even been one of the Russian competitors at the<br />

Chopin Competition in Warsaw, though he achieved only an honourable<br />

mention. His performing style was very individual. ‘Shostakovich<br />

emphasised the linear aspect of music and was very precise in all<br />

the details of performance,’ recalled a friend, ‘he used little rubato<br />

in his playing, and it lacked extreme dynamic contrasts. It was an<br />

‘anti-sentimental’ approach to playing which showed incredible<br />

clarity of thought.’<br />

He wrote this concerto for himself to play, composing it soon after<br />

completing the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and the 24 Preludes<br />

for Piano, and gave the first performance with members of the<br />

Leningrad Philharmonic conducted by Fritz Stiedry on 13 October 1933.<br />

Shostakovich twice recorded the work, and there is even a brief film<br />

clip of him playing the finale at a recklessly fast tempo.<br />

For a decade Shostakovich had taken full advantage of the excitement<br />

and confusion that reigned in post-Revolutionary Russia, producing<br />

a vast body of work that ranged from the modernist brutalism of<br />

the Second and Third Symphonies to the biting satire of The Nose,<br />

from light-hearted ballet scores to the deep seriousness of Lady<br />

Macbeth of Mtsensk. The concerto is one of his most accessible<br />

and justly popular works from this period. Short and compact, the<br />

concerto constantly teases the listener with half-quotations, parodies<br />

and sudden changes of direction. Although it has its moments of<br />

seriousness, they are more apparent than real and tend to be swept<br />

aside by the anarchic humour which was a speciality of the young<br />

Shostakovich. Influences of Ravel, Prokofiev, Gershwin and Stravinsky<br />

4 Programme Notes<br />

can be heard, but equally important is Shostakovich’s own approach<br />

to music for stage and film.<br />

One account suggests that Shostakovich’s initial idea was for a solo<br />

trumpet concerto. Whether there is any truth in this or not, the final<br />

result is by no means a double concerto for equally-matched soloists,<br />

for the piano is very much in the foreground all the time. The trumpet<br />

plays a major role, however, often a thoroughly subversive one, and<br />

achieves a kind of lunatic glory in the Rossini-meets-Mickey-Mouse<br />

conclusion.<br />

Programme note © Andrew Huth<br />

More great pianists with the LSO this summer…<br />

Thu 26 <strong>May</strong> 7.30pm<br />

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 2<br />

with Mitsuko Uchida piano<br />

Thu 2 Jun 7.30pm<br />

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 1<br />

with Mitsuko Uchida piano<br />

Tue 14 & Thu 16 Jun 7.30pm<br />

Schumann Piano Concerto<br />

with Murray Perahia piano<br />

Tickets from £8<br />

Choose your own seats online at<br />

lso.co.uk or call 020 7638 8891

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)<br />

Piano Concerto No 2 in F Major Op 102 (1957)<br />

1 Allegro<br />

2 Andante<br />

3 Allegro<br />

Yefim Bronfman piano<br />

Shostakovich composed six concertos altogether, but while the<br />

two violin concertos (both intended for David Oistrakh) and the two<br />

cello concertos (for Mstislav Rostropovich) count among his most<br />

searching, personal works, the piano concertos are very much on the<br />

lighter side. They also show the radical differences that Shostakovich’s<br />

approach to composition had undergone in 24 years. The first, for<br />

all its good humour, was a product of Russian post-revolutionary<br />

modernism where the high spirits are expressed through a kaleidoscope<br />

of teasing parodies. By the time he composed the Second Piano<br />

Concerto, he had undergone two official condemnations and had<br />

learned to avoid trouble by adopting a more restrained language,<br />

which in his darker and more serious works becomes a mask where<br />

classical forms and procedures are moulded to his own purposes.<br />

That said, the Second Piano Concerto is one of the most straight-<br />

forward and uncomplicated pieces he ever composed, its humour<br />

untinged by sarcasm or bitterness. He wrote it not for himself but for<br />

his son Maxim, who gave the first performance on his 19th birthday<br />

on 10 <strong>May</strong> 1957 (three years earlier Shostakovich had written the<br />

little Concertino for Two Pianos for father and son to play together).<br />

Maxim was a fine pianist but never aimed to become a great virtuoso.<br />

Although the Concerto’s solo writing is always highly effective,<br />

it avoids the bravura and extreme difficulties of the First.<br />

The Second Piano Concerto is as lighthearted as the First, though in a<br />

gentler and perhaps more innocent way. There is nothing provocative,<br />

controversial or experimental here, just the skill and imagination that<br />

Shostakovich devoted to all his music, whether deeply serious or<br />

intended mainly for entertainment. The Concerto’s outward shape<br />

is quite conventional, with a three-movement structure and clear<br />

cut form, so that nothing disturbs its simplicity and directness.<br />

The first movement is in a quick march tempo, its character set by<br />

the bassoon opening; the initial piano texture – left and right hands<br />

playing one or two octaves apart – is a common feature of the solo<br />

writing throughout the Concerto. The second movement, with reduced<br />

orchestra, has the mood and textures of a nocturne. It leads directly<br />

into the high-spirited finale, where the basic duple metre is wittily<br />

subverted by the 7/8 metre of the secondary theme.<br />

Programme note © Andrew Huth<br />

Dmitri Shostakovich – Composer Profile<br />

After early piano lessons with his mother, Shostakovich enrolled at the<br />

Petrograd Conservatoire in 1919. He announced his Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

of 1937 as ‘a Soviet artist’s practical creative reply to just criticism’.<br />

A year before its premiere he had drawn a stinging attack from<br />

Soviet mouthpiece Pravda, in which his initially successful opera<br />

Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was condemned for its extreme<br />

modernism. With the Fifth <strong>Symphony</strong> came acclaim not only from<br />

the Russian audience, but also from musicians and critics overseas.<br />

Shostakovich lived through the first months of the German siege of<br />

Leningrad serving as a member of the auxiliary fire service. In July<br />

he began work on his Seventh <strong>Symphony</strong>, completing the defiant<br />

finale after his evacuation in October, dedicating the score to the<br />

city. A copy was despatched by way of an American warship to<br />

the US, where it was broadcast by the NBC <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>.<br />

In 1943 Shostakovich completed his Eighth <strong>Symphony</strong>, its emotionally<br />

shattering music compared by one critic to Picasso’s Guernica.<br />

In 1948 Shostakovich and other leading composers were forced by<br />

the Soviet cultural commissar, Andrey Zhdanov, to concede that their<br />

work represented ‘most strikingly the formalistic perversions and<br />

anti-democratic tendencies in music’, a crippling blow to his artistic<br />

freedom that was healed only after the death of Stalin in 1953.<br />

Shostakovich answered his critics later that year with the powerful<br />

Tenth <strong>Symphony</strong>, in which he portrays ‘human emotions and<br />

passions’, rather than the collective dogma of Communism.<br />

Profile © Andrew Stewart<br />

Programme Notes<br />

5

Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> No 3 in D Major Op 29 (‘Polish’) (1875)<br />

1 Moderato assai (Tempo di marcia funebrae) – Allegro brillante<br />

2 Alla tedesca<br />

3 Andante<br />

4 Scherzo<br />

5 Allegro con fuoco (Tempo di polacca)<br />

Composed between two of his most popular works, the First<br />

Piano Concerto and Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky’s Third <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

deliberately avoids the expression of any deep personal emotion<br />

but demonstrates instead the composer’s growing involvement<br />

in a wider and more objective symphonic tradition. It was written<br />

in the summer of 1875, when Tchaikovsky was free of his teaching<br />

duties at the Moscow Conservatory. Visiting the country houses of<br />

friends and relatives, he drafted the symphony in barely two weeks<br />

and then took enormous trouble over the final orchestral score.<br />

It was first performed on 19 November 1875 in Moscow, conducted<br />

by Nikolay Rubinstein.<br />

The nickname ‘Polish’, which seems to have been coined when<br />

Sir August Manns gave the symphony its first British performance<br />

at the Crystal Palace in 1899, is quite irrelevant. While the Second<br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> is known as the ‘Ukrainian’ or ‘Little Russian’ because it<br />

makes prominent use of Ukrainian folk tunes, the finale of the Third<br />

features the polonaise not as an expression of national colour but<br />

simply as a stylised dance rhythm. Tchaikovsky was consciously<br />

moving away from his brief but close involvement with the Russian<br />

national composers, finding their dogmatic approach too restricting.<br />

Instead of a heavy dependence on folk themes, which may be<br />

colourful in themselves but tend to be self-contained, Tchaikovsky<br />

is here working with material that is on the surface less distinctive,<br />

but which allows for more elaborate development and more subtle<br />

relationships between themes and movements. Even so, every<br />

detail of the symphony bears the personal stamp of the composer<br />

who admitted that ‘As regards the Russian element in general in my<br />

music … I grew up in the backwoods, saturating myself from earliest<br />

childhood with the inexplicable beauty of the characteristics of<br />

Russian folksong’.<br />

6 Programme Notes<br />

Tchaikovsky’s only symphony in a major key opens with a minor-key<br />

introduction, Tempo di marcia funebre, but this funeral march is more<br />

an indication of style and tempo than any particular expression of<br />

grief. Halting phrases in the dominant key build up suspense with a<br />

gradual acceleration towards the main body of the movement, whose<br />

three themes are treated with many inventive rhythmic shifts.<br />

The three central movements are more lightly scored. The Alla<br />

tedesca, a German dance, is in George Balanchine’s description<br />

‘another of Tchaikovsky’s marvellous waltzes, a whole ballet scene<br />

exquisitely orchestrated’. The central trio keeps the same basic pulse<br />

but sounds faster because of the shorter note-values, a stream of<br />

quaver triplets with a distinct flavour of Schumann or Mendelssohn.<br />

The wind solos that open the deeply expressive slow movement mark<br />

it as both the most Russian and the most personal music heard so far.<br />

The triplet figures that appear later can be heard as a development of<br />

those in the second movement, and are heard to very evocative effect<br />

in the coda, with its echoes of Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique. In the<br />

fourth movement orchestral texture becomes an essential part of the<br />

music’s effect: the strings are muted throughout, giving a spectral<br />

quality to what is essentially a single line of running semiquavers.<br />

For the opening of the trio section Tchaikovsky recycled an idea<br />

from a cantata he had hastily written three years earlier for the<br />

bicentenary of the birth of Peter the Great.<br />

The finale mirrors the first movement as an exercise in orchestral<br />

sonority and brilliance. While for Chopin the Polonaise was a vehicle<br />

for his patriotism, proud, heroic or tragic by turns, Tchaikovsky here<br />

treats the dance as something grand and ceremonial, as he would do<br />

again two years later to convey the aristocratic world of St Petersburg<br />

at the opening of the last act of Eugene Onegin.<br />

Programme note © Andrew Huth<br />

Andrew Huth is a musician, writer and translator who writes<br />

extensively on French, Russian and Eastern European music.

Valery Gergiev<br />

Conductor<br />

‘The vigour of Gergiev’s interpretation,<br />

all darting flashes of colour and<br />

contrast, was immensely appealing’<br />

The Guardian on Valery Gergiev<br />

and the LSO, March 11<br />

Principal Conductor of the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong><br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> since January 2007, Valery Gergiev<br />

performs regularly with the LSO at the Barbican,<br />

at the Proms and at the Edinburgh Festival,<br />

as well as on regular tours of Europe, North<br />

America and Asia. During the 2010/11 season<br />

has led them in appearances in Germany,<br />

France, Switzerland, Japan and the US.<br />

Valery Gergiev is also Artistic and General<br />

Director of the Mariinsky Theatre, founder<br />

and Artistic Director of the Stars of the<br />

White Nights Festival and New Horizons<br />

Festival in St Petersburg, the Moscow Easter<br />

Festival, the Gergiev Rotterdam Festival, the<br />

Mikkeli International Festival, and the Red<br />

Sea Festival in Eilat, Israel. He succeeded<br />

Sir Georg Solti as conductor of the World<br />

Valery Gergiev © Gautier Deblonde<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong> for Peace in 1998 and has led them<br />

this season in concerts in Abu Dhabi.<br />

Gergiev’s inspired leadership of the Mariinsky<br />

Theatre since 1988 has taken the Mariinsky<br />

ensembles to 45 countries and has brought<br />

universal acclaim to this legendary institution,<br />

now in its 227th season. Having opened a new<br />

concert hall in St Petersburg in 2006, Maestro<br />

Gergiev looks forward to the opening of the<br />

new Mariinsky Opera House in summer 20<strong>12</strong>.<br />

Born in Moscow, Valery Gergiev studied<br />

conducting with Ilya Musin at the Leningrad<br />

Conservatory. Aged 24 he won the Herbert<br />

von Karajan Conductors Competition in Berlin<br />

and made his Mariinsky Opera debut one<br />

year later in 1978 conducting Prokofiev’s<br />

War and Peace. In 2003 he led St Petersburg’s<br />

300th anniversary celebrations, and opened<br />

the Carnegie Hall season with the Mariinsky<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, the first Russian conductor to do<br />

so since Tchaikovsky conducted the Hall’s<br />

inaugural concert in 1891.<br />

Now a regular figure in all the world’s major<br />

concert halls, this season he led the LSO<br />

and the Mariinsky <strong>Orchestra</strong> in a symphonic<br />

Centennial Mahler Cycle in New York. Gergiev<br />

has led several cycles previously in New York<br />

including Shostakovich, Stravinsky, Prokofiev,<br />

Berlioz and Richard Wagner’s Ring. He has<br />

also introduced audiences to several rarely<br />

performed Russian operas.<br />

Valery Gergiev’s many awards include a<br />

Grammy, the Dmitri Shostakovich Award,<br />

the Golden Mask Award, People’s Artist of<br />

Russia Award, the World Economic Forum’s<br />

Crystal Award, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize,<br />

Netherlands’ Knight of the Order of the Dutch<br />

Lion, Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun, Valencia’s<br />

Silver Medal, the Herbert von Karajan prize and<br />

the French Order of the Legion of Honour.<br />

He has recorded exclusively for Decca<br />

(Universal Classics), and appears also on<br />

the Philips and Deutsche Grammophon<br />

labels. Currently recording for LSO Live,<br />

his releases include Mahler Symphonies<br />

Nos 1–8, Rachmaninov <strong>Symphony</strong> No 2,<br />

Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet which won the<br />

BBC Music Magazine Disc of the Year and<br />

Bartók Duke Bluebeard’s Castle.<br />

His recordings on the Mariinsky Label are<br />

Shostakovich The Nose and Symphonies<br />

Nos 1, 2, 11 and 15, Tchaikovsky 18<strong>12</strong> Overture,<br />

Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 3 and<br />

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Rodion<br />

Shchedrin The Enchanted Wanderer,<br />

Stravinsky Les Noces and Oedipus Rex<br />

and Wagner Parsifal, many of which have<br />

also won awards, including four Grammy<br />

nominations.<br />

The Artists<br />

7

Yefim Bronfman<br />

Piano<br />

‘A marvel of digital dexterity,<br />

warmly romantic sentiment,<br />

and jaw-dropping bravura.’<br />

The Chicago Tribune on<br />

Yefim Bronfman, March 11<br />

Yefim Bronfman is widely regarded as<br />

one of the most talented virtuoso pianists<br />

performing today. His commanding technique<br />

and exceptional lyrical gifts have won him<br />

consistent critical acclaim and enthusiastic<br />

audiences worldwide, whether for his solo<br />

recitals, his prestigious orchestral engagements<br />

or his rapidly growing catalogue of recordings.<br />

Yefim Bronfman emigrated to Israel with his<br />

family in 1973, and made his international<br />

debut two years later with Zubin Mehta and<br />

the Montreal <strong>Symphony</strong>. He made his New<br />

York Philharmonic debut in <strong>May</strong> 1978, his<br />

Washington recital debut in March 1981 at<br />

the Kennedy Center and his New York recital<br />

debut in January 1982.<br />

Bronfman was born in Tashkent, in the Soviet<br />

Union, on 10 April 1958. In Israel he studied<br />

with pianist Arie Vardi, head of the Rubin<br />

Academy of Music at Tel Aviv University.<br />

In the United States, he studied at The Juilliard<br />

School, Marlboro and the Curtis Institute,<br />

and with Rudolf Firkusny, Leon Fleisher<br />

and Rudolf Serkin.<br />

Bronfman’s 2010/11 European season<br />

highlights included a tour with the Vienna<br />

Philharmonic playing the concerto written<br />

for him by Esa-Pekka Salonen and with<br />

Salonen and the Philharmonia <strong>Orchestra</strong>,<br />

a two-season project of the three Bartók<br />

concertos. In partnership with Berlin’s<br />

Staatskapelle and Daniel Barenboim, all three<br />

Bartók concertos will again be featured in<br />

Berlin, Vienna and Paris. Return engagements<br />

in Europe include the Berlin Philharmonic,<br />

Royal Concertgebouw, Israel Philharmonic,<br />

Frankfurt Radio, Santa Cecilia Rome and<br />

Munich Philharmonic.<br />

Bronfman works regularly with an illustrious<br />

group of conductors, including Daniel<br />

Barenboim, Herbert Blomstedt, Christoph<br />

von Dohnányi, Charles Dutoit, Christoph<br />

Eschenbach, Valery Gergiev, Mariss Jansons,<br />

Lorin Maazel, Kurt Masur, Zubin Mehta,<br />

Esa-Pekka Salonen, Yuri Temirkanov, Franz<br />

Welser-Möst, and David Zinman. Summer<br />

engagements have regularly taken him to<br />

the major festivals of Europe and the US.<br />

Widely praised for his solo, chamber and<br />

orchestral recordings, he was awarded a<br />

Grammy in 1997 for his recording of the<br />

three Bartók Piano Concertos with Esa-Pekka<br />

Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.<br />

His discography also includes the complete<br />

Prokofiev Piano Sonatas; all five of the<br />

Prokofiev Piano Concertos, nominated for<br />

both Grammy and Gramophone Awards; and<br />

Rachmaninov’s Piano Concertos Nos 2 and 3.<br />

His most recent releases are Tchaikovsky’s<br />

Piano Concerto No 1 with Mariss Jansons and<br />

the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen<br />

Rundfunks, a recital disc Perspectives to<br />

complement Bronfman’s designation as a<br />

Carnegie Hall ‘Perspectives’ artist for the<br />

2007/08 season, and recordings of all the<br />

Beethoven Piano Concertos as well as the<br />

Triple Concerto together with violinist<br />

Gil Shaham, cellist Truls Mørk and the<br />

Tönhalle <strong>Orchestra</strong> Zürich under David<br />

Zinman for the Arte Nova/BMG label. His<br />

recordings with Isaac Stern include the<br />

Brahms Violin Sonatas, a cycle of the Mozart<br />

Sonatas for Violin and Piano, and the Bartók<br />

Violin Sonatas. Coinciding with the release<br />

of the Fantasia 2000 soundtrack, Bronfman<br />

was featured on his own Shostakovich album,<br />

performing the two Piano Concertos with<br />

the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Esa-Pekka<br />

Salonen conducting, and the Piano Quintet.<br />

In 2002, Sony Classical released his two-<br />

piano recital (with Emanuel Ax) of works<br />

by Rachmaninov, which was followed in<br />

March 2005 by their second recording of<br />

works by Brahms.<br />

8 The Artists Yefim Bronfman © Dario Acosta

Philip Cobb<br />

Trumpet<br />

As a youngster, Philip regularly featured as a soloist on both the<br />

cornet and the trumpet throughout the UK and abroad alongside his<br />

brother Matthew and their father Stephen. In more recent years he<br />

has appeared as a soloist in his own right, and was recently featured<br />

as a solo performer in <strong>London</strong>’s Royal Albert Hall, as well as at the<br />

International Trumpet Guild conference in Boston, US.<br />

Philip is a former student of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama,<br />

having studied with Principal Trumpet of the <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic<br />

<strong>Orchestra</strong>, Paul Beniston, and also with renowned trumpet soloist<br />

Alison Balsom. Shortly after graduation and following trials with<br />

the <strong>London</strong> Philharmonic and Hallé orchestras, Philip accepted<br />

his current position as Principal Trumpet with the LSO.<br />

In 2006 Philip competed in the prestigious Maurice André International<br />

Trumpet Competition. With former prize winners going on to achieve<br />

international acclaim as both soloists and orchestral performers,<br />

Philip was awarded one of the major prizes in the competition as<br />

the Most Promising Performer. He was also awarded the ‘Candide<br />

Award’ at the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong>’s Brass Academy in 2008.<br />

In September 2007 Philip released his debut solo CD, Life Abundant,<br />

with the Cory Band and Organist Ben Horden.<br />

Gergiev’s Tchaikovsky<br />

Further your Tchaikovsky experience<br />

and join Valery Gergiev and the LSO on<br />

a journey through the quintessentially<br />

Romantic composer’s complete<br />

symphonies.<br />

Wed 21 Sep 2011<br />

All-Tchaikovsky <strong>programme</strong> featuring<br />

the winners of the XIV International<br />

Tchaikovsky Competition<br />

Sun 25 Sep 2011<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 4<br />

Brahms Piano Concerto No 1<br />

with Nelson Freire<br />

Thu 24 Nov 2011<br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 5<br />

Sofia Gubaidulina Fachwerk<br />

with Geir Draugsvoll<br />

Prokofiev <strong>Symphony</strong> No 1 (‘Classical’)<br />

Thu 23 Feb 20<strong>12</strong><br />

Tchaikovsky <strong>Symphony</strong> No 6<br />

(‘Pathétique’)<br />

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No 1<br />

with Sarah Chang<br />

Tickets from £10 on sale now<br />

Box Office<br />

020 7638 8891 (bkg fee)<br />

lso.co.uk (reduced bkg fee)<br />

<strong>London</strong> <strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Living Music<br />

The Artists<br />

9

10<br />

The Symphonies of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky<br />

by Andrew Huth<br />

Tchaikovsky’s symphonies<br />

are both musical and human<br />

dramas, and he took the<br />

writing of them very seriously.<br />

He certainly didn’t see the symphony as an abstract formal idea.<br />

Defending the Fourth in a letter to his favourite pupil Sergei Taneyev,<br />

he wrote ‘I should be sorry if symphonies that mean nothing should<br />

flow from my pen, consisting solely of a progression of harmonies,<br />

rhythms and modulations’. He went on to call the symphony<br />

‘the most purely lyrical of musical forms. Shouldn’t a symphony<br />

reveal those wordless urges that hide in the heart, asking earnestly<br />

for expression?’.<br />

That is a very Romantic, 19th-century point of view, just what we’d<br />

expect from so volatile and emotional a composer as Tchaikovsky.<br />

What it doesn’t reflect is the intellectual effort he devoted to each<br />

of his six symphonies. He hated theorising, particularly in public, and<br />

distrusted verbal explanations, but the fact remains that in order to<br />

express those ‘wordless urges’, he had to think deeply and carefully<br />

about the ‘harmonies, rhythms and modulations’ which are essential<br />

to large-scale form and structure. It was often a difficult process for<br />

him. A letter written to his brother Anatoly while he was composing<br />

the First <strong>Symphony</strong> could stand for all his troubles. He complains<br />

about his nerves (‘...in an awful state because of my symphony, which<br />

is not going well at all...’); to habitual self-doubt he adds a touch of<br />

Tchaikovsky’s Symphonies<br />

self-pity (‘...the thought that I am going to die soon and will not have<br />

time to finish my symphony’) and, for good measure, includes the sort<br />

of resolution he was to make and break until the end of his life<br />

(‘Since yesterday I have stopped drinking vodka, wine and strong tea’).<br />

The First <strong>Symphony</strong> turned out to be full of natural, spontaneous<br />

talent, and contains everything that listeners have always prized in<br />

Tchaikovsky’s music. Later works would be more subtly composed;<br />

but from the beginning there is colour, drama, melody, and an<br />

unmistakable personality in this music. Mendelssohn and Schumann<br />

are the closest models for its overall shape, although the music never<br />

sounds like either of these, or indeed any other German composer:<br />

Tchaikovsky was particularly careful not to recall the procedures or<br />

gestures of Beethoven, who was in many ways his exact opposite as<br />

both man and musician.<br />

With the Second <strong>Symphony</strong>, it seemed that the young Tchaikovsky<br />

had identified himself closely with the aims of the Russian Nationalist<br />

composers. They greatly admired its vigorous, clear orchestration,<br />

especially the fresh wind writing; but what they most prized was<br />

the way in which Tchaikovsky found apparently endless ways of

presenting his folk-like material, inventing accompaniments and<br />

variations that preserved the original character of the melodies while<br />

showing them off from ever-varying perspectives. The Third, however,<br />

marks a step away from Nationalism towards a more objective and<br />

international style. With its five movements, it is actually closer to<br />

Tchaikovsky’s idea of a suite than a symphony, and its somewhat<br />

detached emotional character has caused it to be the least known of<br />

the six – unjustly, for it was an important step towards the remarkable<br />

achievements of the last three symphonies.<br />

‘Shouldn’t a symphony reveal<br />

those wordless urges that<br />

hide in the heart, asking<br />

earnestly for expression?’<br />

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky<br />

In each of these works Tchaikovsky had to discover a new kind of<br />

balance between the demands of symphonic structure and his<br />

personal lyrical style. Expressive melody is always the most striking<br />

feature, and the melodic current that leads the listener through these<br />

large structures is designed to articulate an inner drama. The original<br />

features of the Fourth are mainly concerned with the material itself<br />

(the ‘harmonies, rhythms and modulations’), and the symphony’s overall<br />

shape reveals an almost desperately-willed progress from internal to<br />

external, from the self-obsessed first movement, through reflections of<br />

the past and the outer world, to images of ‘the people’ in the finale –<br />

something which may very well reflect Tchaikovsky’s admiration for<br />

Tolstoy, whose Anna Karenina had recently been serialised.<br />

Ten years separate the Fourth from the Fifth, a period during which<br />

Tchaikovsky’s life had become more stable and his audience more<br />

international. The Fifth is more self-contained, more consciously<br />

related to Western symphonic traditions, and aims (with some<br />

curiously ambiguous results) to be more balanced emotionally.<br />

There is little sign of the traditional German fondness for close<br />

motivic relationships, but the clinging melancholy and nostalgia<br />

that is so much a part of Tchaikovsky’s character is set within a<br />

traditionally classical structure that balances inward melancholy<br />

against an aspiration towards outward-looking strength.<br />

Tchaikovsky’s great achievement in the Sixth was to devise a<br />

structure which seems to arise from the nature of the melodic ideas<br />

themselves. It is a drama of contrasts, or in the terms Tchaikovsky<br />

himself was obviously thinking of, personal passion struggling<br />

against hostile forces. Questions of the correct balance between<br />

lyrical expression and formal balance, between Western and Russian<br />

approaches, are irrelevant in the face of this music’s overwhelming<br />

emotional effect. In the 19th century a symphony beginning in a minor<br />

key was generally planned as a darkness-to-light affair. The slow-<br />

to-slow, darkness-to-darkness of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth contradicts all<br />

expectations, and its bleak message is conveyed with a power that<br />

leaves one in no doubt either of Tchaikovsky’s musical mastery or the<br />

strength of his feelings. It is one of those rare works which open up<br />

new areas of musical experience.<br />

Article © Andrew Huth<br />

Send us your thoughts on<br />

tonight’s concert<br />

Using a smartphone QR code reader,<br />

scan this barcode to be taken to our<br />

mobile site Reviews page, or visit<br />

londonsymphonyorchestra.mobi<br />

Tchaikovsky’s Symphonies<br />

11

On stage<br />

First Violins<br />

Gordan Nikolitch Leader<br />

Carmine Lauri<br />

Lennox Mackenzie<br />

Nigel Broadbent<br />

Ginette Decuyper<br />

Jörg Hammann<br />

Michael Humphrey<br />

Maxine Kwok-Adams<br />

Claire Parfitt<br />

Harriet Rayfield<br />

Colin Renwick<br />

Ian Rhodes<br />

Sylvain Vasseur<br />

Alina Petrenko<br />

Erzsebet Racz<br />

Sarah Sew<br />

Second Violins<br />

Evgeny Grach<br />

Sarah Quinn<br />

Miya Vaisanen<br />

David Ballesteros<br />

Matthew Gardner<br />

Belinda McFarlane<br />

Iwona Muszynska<br />

Philip Nolte<br />

Paul Robson<br />

Caroline Frenkel<br />

Oriana Kriszten<br />

Katerina Mitchell<br />

Stephen Rowlinson<br />

Julia Rumley<br />

<strong>12</strong> The <strong>Orchestra</strong><br />

Violas<br />

Edward Vanderspar<br />

Gillianne Haddow<br />

Malcolm Johnston<br />

Regina Beukes<br />

German Clavijo<br />

Richard Holttum<br />

Robert Turner<br />

Nancy Johnson<br />

Martin Schaefer<br />

Michelle Bruil<br />

Philip Hall<br />

Caroline O’Neill<br />

Cellos<br />

Timothy Hugh<br />

Floris Mijnders<br />

Alastair Blayden<br />

Jennifer Brown<br />

Mary Bergin<br />

Noel Bradshaw<br />

Daniel Gardner<br />

Hilary Jones<br />

Amanda Truelove<br />

Susan Sutherley<br />

Double Basses<br />

Rinat Ibragimov<br />

Nicholas Worters<br />

Patrick Laurence<br />

Michael Francis<br />

Jani Pensola<br />

Simo Vaisanen<br />

Benjamin Griffiths<br />

Adam Wynter<br />

Flutes<br />

Gareth Davies<br />

Adam Walker<br />

Patricia Moynihan<br />

Piccolo<br />

Sharon Williams<br />

Oboes<br />

Emanuel Abbühl<br />

Emmanuel Laville<br />

Katie Bennington<br />

Clarinets<br />

Andrew Marriner<br />

Chris Richards<br />

Chi-Yu Mo<br />

Bassoons<br />

Fredrik Ekdahl<br />

Joost Bosdijk<br />

Horns<br />

Timothy Jones<br />

David Pyatt<br />

Angela Barnes<br />

Jonathan Lipton<br />

Estefanía Beceiro Vazquez<br />

Trumpets<br />

Roderick Franks<br />

Gerald Ruddock<br />

Nigel Gomm<br />

Trombones<br />

Dudley Bright<br />

James <strong>May</strong>nard<br />

Robert Holliday<br />

Bass Trombone<br />

Paul Milner<br />

Tuba<br />

Patrick Harrild<br />

Timpani<br />

Nigel Thomas<br />

Percussion<br />

Neil Percy<br />

LSO String<br />

Experience Scheme<br />

Established in 1992, the<br />

LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme enables young string<br />

players at the start of their<br />

professional careers to gain<br />

work experience by playing in<br />

rehearsals and concerts with<br />

the LSO. The scheme auditions<br />

students from the <strong>London</strong><br />

music conservatoires, and 20<br />

students per year are selected<br />

to participate. The musicians<br />

are treated as professional<br />

’extra’ players (additional to<br />

LSO members) and receive<br />

fees for their work in line with<br />

LSO section players. Students<br />

of wind, brass or percussion<br />

instruments who are in their<br />

final year or on a postgraduate<br />

course at one of the <strong>London</strong><br />

conservatoires can also<br />

benefit from training with LSO<br />

musicians in a similar scheme.<br />

The LSO String Experience<br />

Scheme is generously<br />

supported by the Musicians<br />

Benevolent Fund and Charles<br />

and Pascale Clark.<br />

Yutaka Shimoda (second<br />

violin), Ilona Bondar (viola)<br />

and Vladimir Waltham (cello)<br />

all took part in rehearsals and<br />

will be performing in both<br />

concerts as part of the LSO<br />

String Experience scheme.<br />

List correct at time of<br />

going to press<br />

See page xv for <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Symphony</strong> <strong>Orchestra</strong> members<br />

Editor Edward Appleyard<br />

edward.appleyard@lso.co.uk<br />

Print<br />

Cantate 020 7622 3401<br />

Advertising<br />

Cabbell Ltd 020 8971 8450