Report of Investigation 196 - arkisto.gsf.fi - Geologian tutkimuskeskus

Report of Investigation 196 - arkisto.gsf.fi - Geologian tutkimuskeskus

Report of Investigation 196 - arkisto.gsf.fi - Geologian tutkimuskeskus

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF FINLAND<br />

<strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong><br />

2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat<br />

around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori

GEOLOGIAN TUTKIMUSKESKUS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF FINLAND<br />

Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong><br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

HIGH PRE-MINING METAL CONCENTRATIONS AND CONDUCTIVITY IN PEAT<br />

AROUND THE TALVIVAARA NICKEL DEPOSIT, EASTERN FINLAND<br />

Unless otherwise indicated, the <strong>fi</strong>gures have been prepared by the authors <strong>of</strong> the publication.<br />

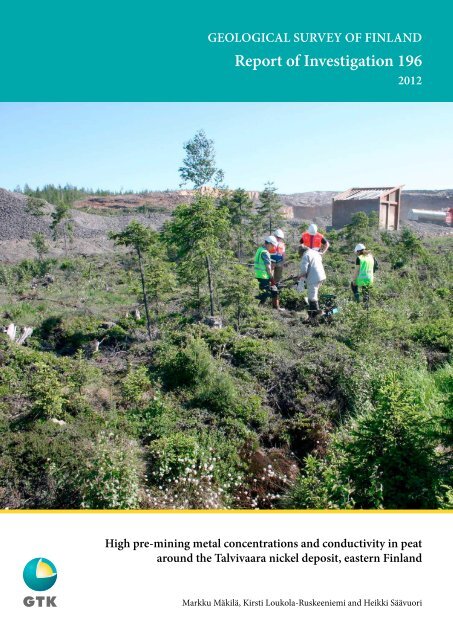

Front cover: Study site M2 in the Talvivaara mine in 2011. The peat samples for the present study<br />

were selected in 2005 when the site was located in the middle <strong>of</strong> a forest, before the large-scale mining<br />

activities began. Photo: Markku Mäkilä, GTK.<br />

Layout: Elvi Turtiainen Oy<br />

Printing house: Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy<br />

Espoo 2012

Mäkilä, M., Loukola-Ruskeeniemi, K. & Säävuori, H. 2012. High pre-mining<br />

metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel<br />

deposit, eastern Finland. Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong><br />

<strong>196</strong>, 36 pages, 31 <strong>fi</strong>gures and 7 tables.<br />

The Talvivaara Ni-Cu-Zn-Co deposit contains more than 1500 Mt <strong>of</strong> lowgrade<br />

ore, and has been mined since 2008 (0.22% Ni, 0.13% Cu, 0.49% Zn,<br />

0.02% Co). Three peat study sites representing different bedrock types and hydrological<br />

conditions were sampled in the Talvivaara area in 2005, before the<br />

large-scale mining activities began. The chemical and physical properties <strong>of</strong><br />

peat were studied from 58 samples. The chemical concentrations <strong>of</strong> peat were<br />

affected by factors such as the capillary transport <strong>of</strong> water through the underlying<br />

sandy till, plant physiology and geochemical processes in peat. The concentrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, U, Zn and S and conductivity were lower<br />

at the study site on mica schist bedrock than in peat at the two study sites underlain<br />

by so-called black schists (metasedimentary rocks rich in graphite and<br />

sulphides). These metals displayed greater concentrations in the bottom layers<br />

<strong>of</strong> Carex (sedge) peat than in the surface layer <strong>of</strong> Sphagnum (moss) -dominated<br />

peat. It seems likely that hydrological conditions at one sloping peatland site<br />

underlain by black schist have been conducive to production and transport <strong>of</strong><br />

acidic surface waters with metal- rich suspension from adjacent Ni-rich black<br />

schist outcrops and glacial till throughout the entire history <strong>of</strong> peat accumulation.<br />

The peat layer evidently functioned in the same way as peat <strong>fi</strong>lters in<br />

the remediation <strong>of</strong> acid mine drainage in present-day mine environments, i.e.<br />

metals were retained in the peat. Ditches also locally reached the underlying<br />

Ni-rich bedrock and/or Ni-rich glacial till. At this black schist study site, pH<br />

values varied between 2.8–3.8 beneath the surface peat layer. These pH values<br />

are lower than can be tolerated by Carex peat-forming plants. The acidity <strong>of</strong><br />

peat changed in the <strong>196</strong>0s when the peat became drier due to drainage <strong>of</strong> the<br />

the peatland, and sulphur oxidized to SO 4 . We conclude that in sulphide-rich<br />

terrain, sulphur concentrations in peat can be high, and leaching <strong>of</strong> sulphur<br />

from peat to surface waters during and after peatland drainage activities may<br />

lead to environmental problems. The conductivity probe developed at the Geological<br />

Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland provides a cost-effective tool for locating sulphiderich<br />

peat formations.<br />

Keywords (GeoRef Thesaurus, AGI): peat, chemical properties, metals, sulfur,<br />

background level, electrical conductivity, mica schist, black schists, nickel, acid<br />

rock drainage, Talvivaara, Sotkamo, Finland<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi, Heikki Säävuori<br />

Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, P. O. Box 96, FI-02151 Espoo, Finland<br />

E-mail: markku.makila@gtk.<strong>fi</strong>, kirsti.loukola-ruskeeniemi@gtk.<strong>fi</strong>, heikki.saavuori@gtk.<strong>fi</strong><br />

ISBN 978-952-217-194-8 (PDF)<br />

ISBN 978-952-217-195-5 (paperback)<br />

ISSN 0781-4240

Mäkilä, M., Loukola-Ruskeeniemi, K. & Säävuori, H. 2012. High pre-mining<br />

metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel<br />

deposit, eastern Finland. <strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong>, 36<br />

sivua, 31 kuvaa ja 7 taulukkoa.<br />

Talvivaaran Ni-Cu-Zn-Co -esiintymä sisältää yli 1500 Mt metallipitoisuudeltaan<br />

suhteellisen alhaista malmia, jota on louhittu vuodesta 2008 lähtien<br />

(0,22 % Ni, 0,13 % Cu, 0,49 % Zn, 0,02 % Co). Talvivaaran alueelta otettiin<br />

vuonna 2005 turvenäytteitä kolmelta suolta, jotka edustavat erilaisia kallioperäalueita<br />

ja hydrologisia olosuhteita. Turpeen kemiallisia ja fysikaalisia ominaisuuksia<br />

tutkittiin 58 näytteestä. Näytteiden kemialliseen koostumukseen<br />

ovat vaikuttaneet monet eri tekijät kuten veden kapillaarinen nousu suon pohjan<br />

hiekkamoreenissa ja turpeen kasvifysiologiset ja geokemialliset prosessit.<br />

Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, U, Zn ja S -pitoisuudet ja johtavuus olivat alemmat kiilleliuske-kallioperässä<br />

olevalla suolla kuin mustaliuskeen (gra<strong>fi</strong>ittia ja sul<strong>fi</strong>deja sisältävien<br />

metasedimenttikivien) päällä olevilla soilla. Nämä metallit esiintyivät<br />

suurempina pitoisuuksina soiden pohjalla saraturpeissa kuin suon pinnan rahkaturpeissa.<br />

Mustaliuskealueella olevalla rinnesuolla hydrologiset olosuhteet<br />

edistivät happamien pintavesien muodostumista ja kulkeutumista turpeeseen<br />

viereisiltä runsaasti nikkeliä sisältäviltä mustaliuskekallioilta ja moreenikerroksista<br />

koko turpeen muodostumishistorian ajan. Ilmeisesti turvekerros toimi<br />

samalla tavalla kuin turvesuodattimet happaman kaivosvalunnan korjaamisessa<br />

nykypäivän kaivosympäristöissä, metalleja pidättyi turpeeseen. Mustaliuskealueella<br />

olevalla rinnesuolla pH-arvot vaihtelivat 2.8–3.8 välillä pintaturvekerroksen<br />

alla. Nämä pH-arvot ovat alempia kuin saraturvetta muodostavat<br />

kasvit kestävät. Turpeen happamuus muuttui <strong>196</strong>0-luvulla, kun turvekerrokset<br />

kuivuivat ojituksen vuoksi ja rikkiä hapettui sulfaatiksi. Alueilla, joissa<br />

kallioperä ja/tai maaperä sisältävät paljon sul<strong>fi</strong>deja, turpeen rikkipitoisuudet<br />

voivat olla korkeita. Rikin kulkeutuminen turpeesta pintavesiin turvemaiden<br />

ojituksen aikana ja sen jälkeen saattaa johtaa ympäristöongelmiin. <strong>Geologian</strong><br />

tutkimuskeskuksessa kehitetty johtavuusluotain tarjoaa kustannustehokkaan<br />

menetelmän sul<strong>fi</strong>dirikkaiden turvekerrosten paikantamiseen.<br />

Asiasanat (Geosanasto, GTK): turve, kemialliset ominaisuudet, metallit, rikki,<br />

taustapitoisuus, sähkönjohtokyky, kiilleliuske, mustaliuskeet, nikkeli, hapan<br />

valuma, Talvivaara, Sotkamo, Suomi<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi, Heikki Säävuori<br />

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, PL 96, 02151 Espoo<br />

S-posti: markku.makila@gtk.<strong>fi</strong>, kirsti.loukola-ruskeeniemi@gtk.<strong>fi</strong>, heikki.saavuori@gtk.<strong>fi</strong>

4<br />

CONTENTS<br />

1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5<br />

2 STUDY AREA ............................................................................................................................... 6<br />

2.1 Bedrock ................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

2.2 Soil .......................................................................................................................................... 7<br />

2.3 Peatlands ................................................................................................................................. 7<br />

2.4 Airborne geophysics ................................................................................................................ 9<br />

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS .................................................................................................... 9<br />

3.1 Sampling .................................................................................................................................. 9<br />

3.2 Laboratory analyses ................................................................................................................10<br />

3.3 Electrical conductivity ............................................................................................................10<br />

4 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................................11<br />

4.1 Chemical concentrations and peat properties <strong>of</strong> study sites ...................................................11<br />

4.2 Correlation between peat properties .......................................................................................24<br />

5 APPLICATION OF ELECTRIC CONDUCTIVITY MEASUREMENTS IN<br />

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES ..................................................................................................32<br />

6 DISCUSSION ...............................................................................................................................32<br />

7 CONCLUSIONS ...........................................................................................................................34<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..............................................................................................................35<br />

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................................35

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Sulphide ores and certain other rock types can influence<br />

elemental abundances in peat (e.g. Salmi<br />

1955, Kokkola & Penttilä 1976, Virtanen 1978,<br />

1990, 1993, 2004, 2005, Virtanen et al. 1997, Virtanen<br />

& Lerssi 2008). Black schists contain sulphides,<br />

weather more easily than other rock types<br />

and cause acid rock drainage and acidi<strong>fi</strong>cation <strong>of</strong><br />

surface waters (Loukola-Ruskeeniemi et al. 1998,<br />

Gustavsson et al. 2012). The chemical composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> peat is affected by numerous factors including<br />

plant physiology, geochemical and microbiological<br />

processes and capillary flow <strong>of</strong> water<br />

through underlying soil. The concentrations <strong>of</strong><br />

soluble ions in peat are dependent, for example,<br />

on the acidity, oxidation conditions, the ion exchange<br />

capacity and the number <strong>of</strong> complex compounds<br />

(Rose et al. 1979).<br />

The mobility <strong>of</strong> potential or actual contaminants<br />

derived from bedrock and soil depends on<br />

(1) their distribution and mode <strong>of</strong> occurrence, (2)<br />

their abundance, i.e. whether minerals are present<br />

in suf<strong>fi</strong>cient quantities to have a measurable effect,<br />

(3) their reactivity, i.e. the energetics, rates and<br />

mechanisms <strong>of</strong> sorption and mineral dissolution<br />

and precipitation relative to the flow rate <strong>of</strong> the<br />

water, and (4) hydrology, i.e. the main flow paths<br />

for contaminated water. Post-dissolution sorption<br />

and precipitation (attenuation) reactions depend<br />

on the chemical behaviour <strong>of</strong> each element,<br />

the composition and pH <strong>of</strong> the solution, aqueous<br />

speciation, temperature, and contact times with<br />

mineral surfaces. For example, little metal attenuation<br />

occurs in waters <strong>of</strong> low pH (

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

heavy metals in peat. Jones and Hao (1993) also<br />

demonstrated elevated concentrations <strong>of</strong> Cd, Cu,<br />

Fe, Pb, and Zn in peat due to industrial activities<br />

in Shef<strong>fi</strong>eld and Manchester. Historical mining<br />

and smelting has been recorded in peat pr<strong>of</strong>iles<br />

in many parts in the world, for example, in the<br />

Basque Country in Spain (Monna et al. 2004) and<br />

South West England (West et al. 1997).<br />

In the present study, results from the analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

three peat pr<strong>of</strong>iles sampled in 2005 around the Tal-<br />

The bedrock in the Talvivaara area consists <strong>of</strong><br />

both Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic rocks<br />

(Figs. 1 and 2). The Talvivaara deposit comprises<br />

two polymetallic ore bodies, Kuusilampi and Kolmisoppi.<br />

The mineral resource is 1 550 million<br />

tonnes at 0.22% <strong>of</strong> nickel, 0.13% <strong>of</strong> copper, 0.02%<br />

<strong>of</strong> cobalt and 0.49% <strong>of</strong> zinc (Talvivaara Mining<br />

Company 2010). Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heino<br />

(1996) classi<strong>fi</strong>ed the Talvivaara C-rich rocks<br />

into two main groups: black schists (Ni-rich, Nipoor,<br />

and Mn-rich subtypes) and graphite-rich<br />

calc-silicate rocks. The black schists at Talvivaara<br />

contain quartz, mica, graphite and sulphides as<br />

the main minerals, with rutile, apatite, zircon,<br />

feldspar and garnet as common accessory minerals.<br />

Quartz occurs in both the matrix and veins,<br />

together with sulphides, mica and feldspar. Pyrite<br />

and pyrrhotite are the dominant sulphide minerals<br />

in the Talvivaara deposit. Pyrite, pyrrhotite<br />

and sphalerite occur both as <strong>fi</strong>ne-grained disseminations<br />

(

7097 7100 7103<br />

N<br />

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

3551 3555<br />

1 km<br />

KOLMISOPPI<br />

M2<br />

M1<br />

KUUSILAMPI<br />

M3<br />

3551 3555<br />

Grey and compact sandy basal glacial till is the<br />

prevailing soil type at Talvivaara and is present<br />

as a thin layer covering the entire area (Murtoniemi<br />

1984). Till fabric alignments vary from<br />

290º to 310º, corresponding to bedrock striation<br />

directions and the general orientation <strong>of</strong> drumlins<br />

and bedrock topography. The upper part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

basal till horizon has locally been reworked with<br />

removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>fi</strong>ne material, during the <strong>fi</strong>nal stages <strong>of</strong><br />

the last deglaciation. Ablation moraines, characterized<br />

by sand and gravel, form discrete mounds<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> the highly undulating topography in<br />

the Talvivaara area, as in much <strong>of</strong> the Sotkamo<br />

region, peatlands are relatively small. Together<br />

with several lakes, occupying low-lying areas<br />

throughout the region, commonly occurring in<br />

depressions between elevated moraine ridges (Fig.<br />

7097 7100 7103<br />

2.2 Soil<br />

2.3 Peatlands<br />

Upper Kaleva (

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

Fig. 3. Soil stratigraphy exposed at study site M2 in 2011. Photo: Ale Grundström, GTK.<br />

Fig. 4. Shaded topographic map <strong>of</strong> the Talvivaara area showing study sites and drainage watershed (broken red line). Old<br />

quarries are also marked on the map in violet. Detailed maps from study site M2 (inset enlargement at lower right) indicate<br />

that the old quarries did not influence the quality <strong>of</strong> surface and ground water affecting peat in M2. Outcrops <strong>of</strong> black schist<br />

containing abundant sulphides (inset enlargement at upper right) induce acid run<strong>of</strong>f and acidi<strong>fi</strong>cation <strong>of</strong> surface waters, after<br />

exposure to the atmosphere and surface waters (Loukola-Ruskeeniemi et al. 1998). Basemap@National Land Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland,<br />

licence no 13/MML/12.<br />

8<br />

7095 7096 7097 7098<br />

Watershed area<br />

Rock outcrop<br />

!( Study sites<br />

Old quarry<br />

m.a.s.l.<br />

High : 250 m<br />

Low : 200 m<br />

3553<br />

M2<br />

3553<br />

M2<br />

3554<br />

M1<br />

M3<br />

0 250 500 1 000 000Metriä<br />

m<br />

3554<br />

7097000 7098000 7099000<br />

7098000<br />

7097000<br />

7096000<br />

7098<br />

7097<br />

7096<br />

7095<br />

m a.s.l<br />

High : 218 m<br />

Low : 210 m<br />

M2<br />

M2<br />

!<br />

0 100 200 300 m

7097 7100 7103<br />

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

3551 3555<br />

3551<br />

!( !(<br />

M2<br />

!( !(<br />

M1<br />

!(<br />

M3<br />

3555<br />

7103<br />

7100<br />

7097<br />

Fig 5. Magnetic map <strong>of</strong> the study area. Fig. 6. Electromagnetic in-phase component map <strong>of</strong> the<br />

study area.<br />

when the sandy till in depressions between moraine<br />

ridges became emergent. Peatland formation<br />

began on mineral soils on the sloping study<br />

site M2 at 7980 years ago (C14-age; Poz-4323).<br />

The rate <strong>of</strong> peat formation has averaged 0.31 mm<br />

Low altitude airborne geophysical surveys <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Talvivaara area were carried out along east-west<br />

flightlines in 1977. The black schist area is clearly<br />

delineated in both magnetic and electromagnetic<br />

maps. The magnetic map in Figure 5 illustrates the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> ferrimagnetic minerals in the bedrock.<br />

Magnetic anomalies in the black schists are<br />

due to the presence <strong>of</strong> monoclinic pyrrhotite and<br />

Sampling <strong>of</strong> the peat layers from study sites M1,<br />

M2 and M3 at Talvivaara was carried out in<br />

2.4 Airborne geophysics<br />

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS<br />

3.1 Sampling<br />

per year. The peat at study site M3 was formed<br />

by progressive paludication <strong>of</strong> forest, the evidence<br />

for which can be seen in wood residues at the bottom<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peat layer.<br />

are indicated by red colors in Figure 5. The electromagnetic<br />

in-phase component map in Figure 6<br />

corresponds generally to the mineral composition<br />

<strong>of</strong> the bedrock, but thick overburden and water<br />

bodies can obscure their distribution. The electrical<br />

anomalies in the black schist area are caused<br />

by both graphite and sulphides.<br />

2005, before the commencement <strong>of</strong> mining at Talvivaara<br />

(Fig. 7).<br />

9

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

Fig. 7. Study site M2 in 2011. The mining area is visible in the<br />

background approximately 100 m from the study site. Photo:<br />

Markku Mäkilä, GTK.<br />

Sampling was carried out using a Russian<br />

core sampler with a diameter <strong>of</strong> 5 cm and length<br />

<strong>of</strong> 50 cm. Peat samples were taken at the in situ<br />

peat deposit study sites as 10 cm sections from<br />

the surface downwards (Fig. 8). Altogether, 58<br />

peat samples were taken. The main peat type and<br />

In the laboratory, peat samples were homogenized<br />

before analysis. The samples were chemically analysed<br />

by ICP-MS and ICP-AES methods. Analyses<br />

were carried out in the laboratory <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland. The samples were<br />

analysed for organic carbon and ash content % <strong>of</strong><br />

Conductivity was measured at the three study<br />

sites from the surface to the bottom <strong>of</strong> the cored<br />

section at intervals <strong>of</strong> 25 cm. During sampling,<br />

conductivity and temperature were measured<br />

with an electric conductivity and temperature<br />

probe (Puranen et al. 1997 and 1999) (Fig. 9). The<br />

sensor was pressed into the peat using the shaft<br />

<strong>of</strong> the core sampler. The temperature sensor consisted<br />

<strong>of</strong> an integrated circuit (AD590), and the<br />

four Wenner electrodes (with a spacing <strong>of</strong> 1.5 cm)<br />

comprising the conductivity sensor operated at<br />

a high frequency (500 Hz) to avoid electrode polarization.<br />

Electrical conductivity correlates with<br />

the nutrient content, temperature and acidity (pH<br />

value) <strong>of</strong> peatland waters.<br />

10<br />

3.2 Laboratory analyses<br />

3.3 Electrical conductivity<br />

Fig. 8. Peat sampling. Photo: Markku Mäkilä, GTK.<br />

the proportions <strong>of</strong> any minor constituents were<br />

determined by visual inspection <strong>of</strong> the peat cores<br />

(Lappalainen et al. 1984). Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation was estimated<br />

according to the 10-degree scale <strong>of</strong> von<br />

Post (1922). In addition, the type <strong>of</strong> subsoil was<br />

recorded.<br />

dry weight, water content % <strong>of</strong> wet weight, pH,<br />

elemental sulphur and major and trace elements<br />

(mg/kg). Dry bulk density per cubic metre <strong>of</strong> peat<br />

(g/m 3 ) was calculated on the basis <strong>of</strong> the water<br />

content (Mäkilä 1994).<br />

Fig. 9. Probe for electrical conductivity and temperature logging<br />

<strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t sediments. P: probe; E: electronics unit; C: Kevlar<br />

cable; S: sampler shaft; L: lifting tool.

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

4 RESULTS<br />

4.1 Chemical concentrations and peat properties <strong>of</strong> study sites<br />

Study site M1 was situated in a schist area outside<br />

the watershed (Figs. 2 and 4). The mire type at<br />

study site M1 represents a transformed pine bog.<br />

The peat layer was 1.8 m thick and mainly consisted<br />

<strong>of</strong> moderately decomposed woody-Sphagnum<br />

(moss) peat with a Carex (sedge) layer at the<br />

bottom. Beneath the peat was a 10 cm layer <strong>of</strong><br />

sandy till with peat (Table 1). The mean humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

degree (H) <strong>of</strong> the peat was 5.5 according on<br />

the 10-degree scale <strong>of</strong> von Post (1922). The average<br />

ash content was 2.4% <strong>of</strong> dry weight, the water<br />

content 87.1% <strong>of</strong> wet weight, and the dry bulk<br />

density 125.3 kg per m 3 in situ (Table 1).<br />

Study site M2 represents peat development on<br />

sloping terrain, which occurs where ground water<br />

is discharges at the surface on a rather steep<br />

slope (Fig. 4). This type <strong>of</strong> peatland usually forms<br />

at the foot <strong>of</strong> a hill. Good drainage and aeration<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peat-generating layer ensures a high degree<br />

<strong>of</strong> peat decomposition, although some remaining<br />

wood residues are well preserved (Fig. 10). Study<br />

site M2 is located within the watershed, subject<br />

Fig. 10. Well-preserved woody residue at study site M2. Photo: Markku Mäkilä, GTK.<br />

to discharge from the Kuusilampi ore deposit,<br />

where the bedrock consists <strong>of</strong> black schists that<br />

are highly fractured and rich in sulphides (Fig. 2).<br />

The mire type at the study site consisted <strong>of</strong><br />

transformed spruce peatland. The peat layer was<br />

2.5 m thick and mainly consisted <strong>of</strong> well decomposed<br />

woody Carex peat. The subsoil was sandy<br />

till (Fig. 3). The mean humi<strong>fi</strong>cation degree (H)<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peat was 6.6. The average ash content was<br />

31.3% <strong>of</strong> dry weight, the water content 85.3% <strong>of</strong><br />

wet weight, and the dry bulk density 135.3 kg per<br />

m 3 in situ (Table 1).<br />

Study site M3 was situated in a black schist area<br />

outside the watershed (Figs. 2 and 4). This site<br />

represented a transformed spruce peatland. The<br />

peat layer was 1.2 m thick and mainly comprised<br />

moderately decomposed woody Sphagnum and<br />

Carex peat. The subsoil was sandy till. The mean<br />

humi<strong>fi</strong>cation degree (H) <strong>of</strong> the peat was 5.2. The<br />

average ash content was 5.6% <strong>of</strong> dry weight, the<br />

water concentration 85.9% <strong>of</strong> wet weight, and the<br />

dry bulk density 132.0 kg per m 3 in situ (Table 1).<br />

11

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

Tables 1, 2 and 3. Concentrations <strong>of</strong> selected trace elements and sulphur, pH, carbon, water, and ash content and dry density. Conductivity is corrected at a temperature <strong>of</strong> 18 o C in peat<br />

at study sites M1, M2 and M3. Metal and sulphur concentrations are presented as mg/kg dry matter. The peat type is described using the following symbols: C Carex (sedge), S Sphagnum<br />

(moss), B Bryales (brown moss), ER Eriophorum (cotton grass), L wood residues, EQ Equisetum (horsetail), N Nanolignidi (dwarf shrub remains). Degree <strong>of</strong> humi<strong>fi</strong>cation 1-10 in von Post’s<br />

scale. Sphagnum-predominant peat is highlighted with light grey and Carex-predominant peat is highlighted with dark grey.<br />

12<br />

Depth Humi<strong>fi</strong>- Peat Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb U Zn S C pH Water Dry Ash Conduccm<br />

cation type mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg % cont. % density % tivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> dry <strong>of</strong> wet in situ <strong>of</strong> dry mS/m<br />

weight weight kg/m3 Table 1.<br />

weight 18 °C<br />

10 2 LS 1.10 10.3 8060 35.7 5.48 18.9 0.21 41.0 2400 43.6 3.4 87.2 100.6 3.5 12.8<br />

20 7 LS 0.87 5.09 4300 6.00 5.33 9.14 0.37 10.1 3200 51.2 3.2 88.3 114.2 3.1 12.8<br />

30 7 LS 0.84 5.41 1410 7.85 4.65 3.32 0.26 11.2 3730 48.3 3.1 86.2 135.4 2.1 12.8<br />

40 5 ERS 0.98 8.25 1210 9.52 5.79 1.87 0.34 7.08 3830 48.7 3.1 85.5 142.5 1.7 8.0<br />

50 5 ERS 0.75 4.79 1190 8.69 4.65 0.95 0.41 5.43 3510 49.8 3.2 84.4 153.6 1.4 8.0<br />

60 5 ERLS 0.72 10.1 1320 10.1 6.26 1.31 0.96 7.63 4110 51.1 3.3 84.4 153.5 1.9 8.0<br />

70 5 ERLS 0.68 10.9 1290 8.65 5.48 0.99 0.97 4.98 4800 51.0 3.3 84.6 151.5 1.8 6.7<br />

80 5 ERLS 1.00 15.5 1260 8.59 6.58 1.07 1.16 5.59 6620 50.9 3.4 86.3 134.5 1.7 6.7<br />

90 5 ERLS 0.88 16.2 1220 7.72 5.74 0.90 1.38 5.24 6250 51.5 3.6 88.2 115.5 1.8 4.3<br />

100 5 CS 1.12 19.2 1220 7.78 6.34 1.35 1.30 4.56 8450 51.6 3.6 90.2 95.5 1.7 4.3<br />

110 7 SC 0.94 18.5 1510 9.18 6.37 2.26 1.25 4.99 6730 51.0 3.5 89.0 107.3 1.9 4.3<br />

120 7 SC 0.87 28.6 1620 8.23 7.19 2.99 2.03 4.48 6850 51.2 3.6 88.7 110.2 2.5 5.1<br />

130 7 SC 0.73 30.8 1600 7.77 6.99 2.74 2.42 4.04 7380 51.8 3.6 87.3 123.8 3.2 5.1<br />

140 6 SC 0.62 26.1 1670 7.92 7.33 3.13 2.33 5.17 7930 52.7 3.7 84.6 150.6 3.0 4.5<br />

150 6 SC 0.69 30.7 1890 8.39 9.04 4.02 2.30 3.95 9970 51.1 3.7 84.3 153.5 3.2 4.5<br />

160 5 SC 1.05 31.5 2010 8.78 12.4 3.59 1.37 6.46 11600 51.5 3.7 87.6 121.0 2.7 4.5<br />

170 5 SC 1.11 18.9 2200 8.87 9.68 1.92 0.77 7.29 11000 51.6 3.9 89.9 98.4 2.2 3.7<br />

180 5 SC 1.43 15.5 2660 10.2 11.4 1.64 0.55 21.3 9030 49.8 3.9 90.4 93.2 3.4 3.7<br />

190 Sandy peat 1.91 47.1 3140 26.5 23.6 3.29 2.07 93.4 8530 35.9 4.1 32.3 3.3<br />

200 Peaty till 6.40 31.8 5900 86.6 29.1 6.98 2.41 38.0 2450 11.5 4.4 81.9 3.3<br />

Average 5.5 0.91 17 2091 10.00 7.04 3.5 1.13 8.92 6522 50.5 3.5 87.1 125.3 2.4 6.7

Table 2.<br />

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Depth Humi<strong>fi</strong>- Peat Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb U Zn S C pH Water Dry Ash Conduccm<br />

cation type mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg % cont. % density % tivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> dry <strong>of</strong> wet in situ <strong>of</strong> dry mS/m<br />

weight weight kg/m 3 weight 18 °C<br />

10 2 NS 2.72 29 26200 89.9 22.9 23.9 0.61 104 2230 43.8 3.5 85.3 100.6 6.6 3.5<br />

20 5 LCS 1.53 73 17000 7.09 17.6 12.7 2.36 36.4 4680 48.2 3.6 84.1 155.5 6.4 3.5<br />

30 6 LCS 1.35 180 13700 6.80 21.4 12.2 3.66 48.2 6740 46.9 3.7 85.1 144.8 10.1 3.5<br />

40 7 SC 2.00 276 25600 21.6 25.9 3.55 3.27 220 9540 40.3 4.2 85.7 135.5 20.8 4.5<br />

50 7 SC 4.06 93 9670 71.0 35.4 1.40 1.56 266 10300 29.7 4.4 86.3 124.7 41.7 4.5<br />

60 8 SC 9.88 94 20100 77.3 77.6 3.84 1.88 317 15700 34.9 4.3 87.1 119.6 29.8 4.5<br />

70 7 LSC 20.4 95 32200 76.9 162 1.33 1.69 568 27100 30.5 3.1 88.0 110.2 31.7 8.5<br />

80 6 SC 20.0 97 33500 85.0 156 1.28 2.00 676 26300 35.1 3.2 89.0 102.7 21.9 8.5<br />

90 7 SC 21.7 120 32300 68.1 148 0.65 2.08 795 26700 30.7 3.3 87.7 113.5 30.3 10.1<br />

100 7 SC 33.9 146 40000 56.0 220 0.53 2.64 1010 35300 26.1 3.3 87.5 114.0 36.7 10.1<br />

110 8 LSC 32.4 184 42400 57.9 230 0.62 3.47 1050 35000 28.0 3.3 87.8 112.0 32.5 10.1<br />

120 8 LSC 39.0 231 47600 54.3 303 0.64 4.47 1490 41100 26.5 3.3 87.7 112.7 34.1 9.5<br />

130 7 LSC 37.8 249 53300 48.7 305 0.69 5.67 1580 46500 25.0 3.2 87.2 117.3 35.2 9.5<br />

140 7 LSC 31.3 316 63700 40.4 286 0.83 6.94 1580 57900 23.8 3.4 86.1 127.9 36.4 11.7<br />

150 7 SC 16.9 292 80600 33.3 237 1.31 7.82 1830 75500 23.2 3.3 83.8 150.6 36.9 11.7<br />

160 7 SC 19.5 300 75100 32.8 244 1.32 7.71 1990 69600 23.5 3.7 84.9 139.6 37.3 11.7<br />

170 8 SC 20.3 324 78900 28.4 272 1.41 8.20 2380 74900 23.5 3.6 84.6 142.9 35.6 12.5<br />

180 7 SC 18.6 285 90700 22.0 260 1.36 6.92 2170 86500 23.2 3.8 84.6 143.1 34.9 12.5<br />

190 6 BC 18.7 234 97700 15.4 265 1.14 5.57 1990 93000 21.1 3.2 85.2 136.5 37.6 16.5<br />

200 6 BC 18.4 227 109000 11.6 293 0.76 5.07 2420 107000 20.6 3.1 84.4 144.9 35.7 16.5<br />

210 6 BC 27.0 194 120000 14.0 451 1.28 3.88 5270 121000 22.2 3.7 85.1 138.1 35.3 16.5<br />

220 6 SC 16.5 114 85600 22.5 292 0.43 3.48 2740 123000 18.8 3.5 83.5 153.5 36.9 21.5<br />

230 7 LSC 12.1 93 74600 23.5 277 0.66 2.64 1050 136000 14.9 3.6 80.3 183.7 43.3 21.5<br />

240 7 LSC 20.8 101 89800 16.6 612 3.44 4.84 1580 136000 16.1 3.2 79.5 192.1 40.9 27.8<br />

250 7 EQLSC 28.1 137 87700 23.4 758 7.06 10.5 4360 126000 24.8 2.8 82.4 165.1 33.7 27.8<br />

260 Peaty till 35.9 334 269000 29.9 1120 15.4 8.77 5400 33700 9.65 68.3 36.7<br />

Average 6.6 19.0 179 57879 40.2 239 3.4 4.4 1501 59744 28.1 3.5 85.3 135.3 31.3 11.9<br />

13

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

14<br />

Table 3.<br />

Depth Humi<strong>fi</strong>- Peat Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb U Zn S C pH Water Dry Ash Conduccm<br />

cation type mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg % cont. % density % tivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> dry <strong>of</strong> wet in situ <strong>of</strong> dry mS/m<br />

weight weight kg/m3 weight 18 °C<br />

10 2 NS 1.41 17.5 4110 46.3 20.9 16.9 1.2 39.1 5090 45.1 3.4 83.3 100.6 6.4 7.3<br />

20 7 LS 1.33 27.4 3880 11.3 27.1 10.1 1.53 29.2 8700 47.9 3.5 83.5 161.9 4.7 7.3<br />

30 7 LS 1.72 20.6 3800 27.4 31.8 3.33 0.91 54.5 9470 48.2 3.6 85.2 144.8 5.2 7.3<br />

40 6 LCS 1.76 15.6 3500 22.9 34.7 1.71 0.96 64.5 9610 48.6 3.7 85.3 143.8 5.3 5.4<br />

50 6 LCS 1.88 12.9 3800 33.4 35.5 1.8 0.98 79.5 9910 47.9 3.8 84.8 148.7 5.9 5.4<br />

60 4 LCS 2.09 16.6 4500 55.3 35.4 1.89 0.58 73.6 10100 47.8 4.2 88.2 114.5 5.1 5.4<br />

70 5 LSC 2.28 15.3 5750 86.3 37.4 0.81 0.53 83.2 12300 47.5 4.1 86.7 129.2 5.6 8.9<br />

80 5 LSC 2.00 20.7 7100 105 40.6 0.86 0.91 93.3 13400 48.0 4.2 87.5 121.2 6.1 10.4<br />

90 5 LSC 1.64 24.2 7780 128 40.4 0.87 1.17 84.8 14500 47.5 4.3 86.6 130.0 6.6 13.6<br />

100 5 LSC 1.43 24.0 7610 120 34.0 0.89 1.03 100 13600 48.3 4.3 86.9 127.3 5.2 13.6<br />

110 5 LSC 1.33 18.8 6950 108 30.1 0.96 0.79 49.8 14900 49.5 4.6 87.8 118.6 4.6 13.6<br />

120 5 LSC 1.20 26.7 8260 124 37.4 1.15 1.42 118 14400 48.8 4.5 85.2 143.8 6.5 15.1<br />

Average 5.2 1.67 20.0 5587 72.3 33.8 3.4 1.0 72.5 11332 47.9 4.0 85.9 132.0 5.6 9.4

Tables 4, 5 and 6. Concentrations <strong>of</strong> selected trace elements, sulphur, pH value, carbon, water, and ash content, dry density and conductivity corrected at a temperature <strong>of</strong> 18 o C at study<br />

sites M1, M2 and M3. Metal and sulphur concentrations are presented as g/m3 <strong>of</strong> peat. The peat type is described with use <strong>of</strong> the following symbols: C Carex (sedge), S Sphagnum (moss),<br />

B Bryales (brown moss), ER Eriophorum (cotton grass), L wood residues, EQ Equisetum (horsetail), N Nanolignidi (dwarf shrub remains). Degree <strong>of</strong> humi<strong>fi</strong>cation 1-10 in von Post’s scale.<br />

Sphagnum-predominant peat is highlighted with light grey and Carex-predominant peat is highlighted with dark grey. Average values don´t include results <strong>of</strong> the sandy peat and peaty till<br />

samples.<br />

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Depth Humi<strong>fi</strong>- Peat Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb U Zn S C pH Water Dry Ash Conduccm<br />

cation type g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 g/m3 % cont. % density % tivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> dry <strong>of</strong> wet in situ <strong>of</strong> dry mS/m<br />

weight weight kg/m3 Table 4.<br />

weight 18 °C<br />

10 2 LS 0.22 1.04 811 3.59 5.48 18.9 0.21 4.12 241 43.6 3.4 87.2 100.6 3.5 12.8<br />

20 7 LS 0.10 0.58 491 0.69 5.33 9.14 0.37 1.15 366 51.2 3.2 88.3 114.2 3.1 12.8<br />

30 7 LS 0.11 0.73 191 1.06 4.65 3.32 0.26 1.52 505 48.3 3.1 86.2 135.4 2.1 12.8<br />

40 5 ERS 0.14 1.18 172 1.36 5.79 1.87 0.34 1.01 546 48.7 3.1 85.5 142.5 1.7 8.0<br />

50 5 ERS 0.12 0.74 183 1.33 4.65 0.95 0.41 0.83 539 49.8 3.2 84.4 153.6 1.4 8.0<br />

60 5 ERLS 0.11 1.55 203 1.55 6.26 1.31 0.96 1.17 631 51.1 3.3 84.4 153.5 1.9 8.0<br />

70 5 ERLS 0.10 1.65 195 1.31 5.48 0.99 0.97 0.75 727 51.0 3.3 84.6 151.5 1.8 6.7<br />

80 5 ERLS 0.13 2.09 170 1.16 6.58 1.07 1.16 0.75 891 50.9 3.4 86.3 134.5 1.7 6.7<br />

90 5 ERLS 0.10 1.87 141 0.89 5.74 0.90 1.38 0.61 722 51.5 3.6 88.2 115.5 1.8 4.3<br />

100 5 CS 0.11 1.83 116 0.74 6.34 1.35 1.30 0.44 807 51.6 3.6 90.2 95.5 1.7 4.3<br />

110 7 SC 0.10 1.99 162 0.99 6.37 2.26 1.25 0.54 722 51.0 3.5 89.0 107.3 1.9 4.3<br />

120 7 SC 0.10 3.15 178 0.91 7.19 2.99 2.03 0.49 755 51.2 3.6 88.7 110.2 2.5 5.1<br />

130 7 SC 0.09 3.81 198 0.96 6.99 2.74 2.42 0.50 914 51.8 3.6 87.3 123.8 3.2 5.1<br />

140 6 SC 0.09 3.93 251 1.19 7.33 3.13 2.33 0.78 1194 52.7 3.7 84.6 150.6 3.0 4.5<br />

150 6 SC 0.11 4.71 290 1.29 9.04 4.02 2.30 0.61 1530 51.1 3.7 84.3 153.5 3.2 4.5<br />

160 5 SC 0.13 3.81 243 1.06 12.4 3.59 1.37 0.78 1403 51.5 3.7 87.6 121.0 2.7 4.5<br />

170 5 SC 0.11 1.86 216 0.87 9.68 1.92 0.77 0.72 1082 51.6 3.9 89.9 98.4 2.2 3.7<br />

180 5 SC 0.13 1.44 248 0.95 11.4 1.64 0.55 1.98 841 49.8 3.9 90.4 93.2 3.4 3.7<br />

190 Sandy peat 35.9 4.1 32.3 3.3<br />

200 Peaty till 11.5 4.4 81.9 3.3<br />

Average 5.5 0.12 2.1 248 1.2 7.04 3.45 1.13 1.0 801 50.5 3.5 87.1 125.3 2.4 6.7<br />

15

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

16<br />

Table 5.<br />

Depth Humi<strong>fi</strong>- Peat Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb U Zn S C pH Water Dry Ash Conduccm<br />

cation type g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 % cont. % density % tivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> dry <strong>of</strong> wet in situ <strong>of</strong> dry mS/m<br />

weight weight kg/m 3 weight 18 °C<br />

10 2 NS 0.27 2.90 2636 9.04 2.30 2.40 0.06 10.5 224 43.8 3.5 85.3 100.6 6.6 3.5<br />

20 5 LCS 0.24 11.3 2644 1.10 2.74 1.98 0.37 5.7 728 48.2 3.6 84.1 155.5 6.4 3.5<br />

30 6 LCS 0.20 26.1 1983 0.98 3.10 1.77 0.53 7.0 976 46.9 3.7 85.1 144.8 10.1 3.5<br />

40 7 SC 0.27 37.4 3470 2.93 3.51 0.48 0.44 29.8 1293 40.3 4.2 85.7 135.5 20.8 4.5<br />

50 7 SC 0.51 11.5 1206 8.85 4.41 0.17 0.19 33.2 1285 29.7 4.4 86.3 124.7 41.7 4.5<br />

60 8 SC 1.18 11.2 2404 9.24 9.3 0.46 0.22 37.9 1878 34.9 4.3 87.1 119.6 29.8 4.5<br />

70 7 LSC 2.25 10.5 3550 8.48 17.9 0.15 0.19 62.6 2988 30.5 3.1 88.0 110.2 31.7 8.5<br />

80 6 SC 2.05 10.0 3439 8.73 16.0 0.13 0.21 69.4 2700 35.1 3.2 89.0 102.7 21.9 8.5<br />

90 7 SC 2.46 13.6 3667 7.73 16.8 0.07 0.24 90.3 3032 30.7 3.3 87.7 113.5 30.3 10.1<br />

100 7 SC 3.87 16.6 4561 6.39 25.1 0.06 0.30 115 4025 26.1 3.3 87.5 114.0 36.7 10.1<br />

110 8 LSC 3.63 20.6 4750 6.49 25.8 0.07 0.39 118 3921 28.0 3.3 87.8 112.0 32.5 10.1<br />

120 8 LSC 4.39 26.0 5362 6.12 34.1 0.07 0.50 168 4630 26.5 3.3 87.7 112.7 34.1 9.5<br />

130 7 LSC 4.44 29.2 6254 5.71 35.8 0.08 0.67 185 5456 25.0 3.2 87.2 117.3 35.2 9.5<br />

140 7 LSC 4.00 40.4 8149 5.17 36.6 0.11 0.89 202 7407 23.8 3.4 86.1 127.9 36.4 11.7<br />

150 7 SC 2.54 44.0 12134 5.01 35.7 0.20 1.18 276 11367 23.2 3.3 83.8 150.6 36.9 11.7<br />

160 7 SC 2.72 41.9 10483 4.58 34.1 0.18 1.08 278 9715 23.5 3.7 84.9 139.6 37.3 11.7<br />

170 8 SC 2.90 46.3 11279 4.06 38.9 0.20 1.17 340 10707 23.5 3.6 84.6 142.9 35.6 12.5<br />

180 7 SC 2.66 40.8 12980 3.15 37.2 0.19 0.99 311 12379 23.2 3.8 84.6 143.1 34.9 12.5<br />

190 6 BC 2.55 32.0 13341 2.10 36.2 0.16 0.76 272 12699 21.1 3.2 85.2 136.5 37.6 16.5<br />

200 6 BC 2.67 32.9 15794 1.68 42.5 0.11 0.73 351 15504 20.6 3.1 84.4 144.9 35.7 16.5<br />

210 6 BC 3.73 26.8 16569 1.93 62.3 0.18 0.54 728 16707 22.2 3.7 85.1 138.1 35.3 16.5<br />

220 6 SC 2.53 17.5 13141 3.45 44.8 0.07 0.53 421 18883 18.8 3.5 83.5 153.5 36.9 21.5<br />

230 7 LSC 2.22 17.1 13701 4.32 50.9 0.12 0.48 193 24977 14.9 3.6 80.3 183.7 43.3 21.5<br />

240 7 LSC 4.00 19.4 17253 3.19 117.6 0.66 0.93 304 26129 16.1 3.2 79.5 192.1 40.9 27.8<br />

250 7 EQLSC 4.64 22.6 14483 3.86 125.2 1.17 1.73 720 20808 24.8 2.8 82.4 165.1 33.7 27.8<br />

260 Peaty till 9.65 68.3 36.7<br />

Average 6.6 2.5 24.3 8209 5.0 34.3 0.4 0.6 213 8817 28.1 3.5 85.3 135.3 31.3 11.9

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Table 6.<br />

Depth Humi<strong>fi</strong>- Peat Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb U Zn S C pH Water Dry Ash Conduccm<br />

cation type g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 g/m 3 % cont. % density % tivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> dry <strong>of</strong> wet in situ <strong>of</strong> dry mS/m<br />

weight weight kg/m 3 weight 18 °C<br />

10 2 NS 0.14 1.76 413 4.66 2.10 1.70 0.12 3.93 512 45.1 3.4 83.3 100.6 6.4 7.3<br />

20 7 LS 0.22 4.44 628 1.83 4.39 1.64 0.25 4.73 1409 47.9 3.5 83.5 161.9 4.7 7.3<br />

30 7 LS 0.25 2.98 550 3.97 4.60 0.48 0.13 7.89 1371 48.2 3.6 85.2 144.8 5.2 7.3<br />

40 6 LCS 0.25 2.24 503 3.29 4.99 0.25 0.14 9.27 1382 48.6 3.7 85.3 143.8 5.3 5.4<br />

50 6 LCS 0.28 1.92 565 4.97 5.28 0.27 0.15 11.82 1473 47.9 3.8 84.8 148.7 5.9 5.4<br />

60 4 LCS 0.24 1.90 515 6.33 4.05 0.22 0.07 8.43 1156 47.8 4.2 88.2 114.5 5.1 5.4<br />

70 5 LSC 0.29 1.98 743 11.15 4.83 0.10 0.07 10.75 1589 47.5 4.1 86.7 129.2 5.6 8.9<br />

80 5 LSC 0.24 2.51 860 12.72 4.92 0.10 0.11 11.31 1624 48.0 4.2 87.5 121.2 6.1 10.4<br />

90 5 LSC 0.21 3.14 1011 16.63 5.25 0.11 0.15 11.02 1884 47.5 4.3 86.6 130.0 6.6 13.6<br />

100 5 LSC 0.18 3.06 969 15.28 4.33 0.11 0.13 12.73 1732 48.3 4.3 86.9 127.3 5.2 13.6<br />

110 5 LSC 0.16 2.23 824 12.81 3.57 0.11 0.09 5.90 1767 49.5 4.6 87.8 118.6 4.6 13.6<br />

120 5 LSC 0.17 3.84 1188 17.84 5.38 0.17 0.20 16.97 2071 48.8 4.5 85.2 143.8 6.5 15.1<br />

Average 5.2 0.22 2.67 731 9.29 4.47 0.44 0.13 9.56 1497 47.9 4.0 85.9 132.0 5.6 9.4<br />

17

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

At study site M2 in the black schist area, the<br />

average concentrations <strong>of</strong> copper, nickel, zinc<br />

and sulphur in the peat were many times higher<br />

than average values reported by Virtanen (2005)<br />

from Ostrobothnia in western Finland (Table 7).<br />

These differences were particularly signi<strong>fi</strong>cant<br />

for zinc, nickel, cobolt and sulphur. At the black<br />

schist study site M3, Zn, Ni and S concentrations<br />

showed the greatest differences when compared<br />

with average values from Ostrobothia. At study<br />

site M1, located in an area <strong>of</strong> mica schists with<br />

black schist intercalations, element concentrations<br />

were closer to the average values <strong>of</strong> Ostrobothnia<br />

(Table 7).<br />

The concentrations <strong>of</strong> Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Zn<br />

and S were greater in peat at black schist study site<br />

M3 than at mica schist study site M1. However,<br />

the above-mentioned concentrations, apart from<br />

those for Mn, were signi<strong>fi</strong>cantly greater at study<br />

18<br />

site M2 in an area where hydrologically modi<strong>fi</strong>ed<br />

peat overlies black schist than at study sites M1 or<br />

M3, (Tables 1−6).<br />

At study sites M1 and M3 the concentrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> cobalt remained relatively constant with increasing<br />

depth (Fig. 11). At M2 the cobalt concentration<br />

increased more than tenfold from the<br />

surface down to a depth <strong>of</strong> 0.3 m, after which the<br />

concentration remained relatively constant.<br />

The copper concentration also increased as a<br />

function <strong>of</strong> depth (Fig. 12). At the black schist<br />

study sites M2 and M3 the peak copper concentration<br />

was recorded at a depth <strong>of</strong> less than half<br />

a metre, while at the mica schist study site M1 the<br />

peak was close to the bottom <strong>of</strong> the peat layer.<br />

The iron concentration increased at all study<br />

sites as a function <strong>of</strong> depth below 50 cm, the largest<br />

increase being recorded at study site M2 (Fig.<br />

13).<br />

Table 7. The average concentrations <strong>of</strong> selected trace elements and sulphur at study sites M1, M2 and M3 at Talvivaara. Results<br />

from peatlands <strong>of</strong> northern Ostrobothnia were used as reference values for comparison (Virtanen 2005). Red background<br />

colour indicates higher concentrations and blue background lower concentrations compared to average values provided by<br />

Virtanen (2005). The Talvivaara ore has rather low Pb concentrations, which is evident in the comparative data: the Pb content<br />

<strong>of</strong> peat at Talvivaara is lower than in Ostrobothnia.<br />

Co Cu Fe Mn Ni Pb Zn S<br />

Study site mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg mg/kg<br />

M1 0.9 17.0 2091 10.0 7.0 3.5 8.9 6522<br />

M2 19.0 179.4 57 879 40.2 238.9 3.4 1501 59 744<br />

M3 1.7 20.0 5587 72.3 33.8 3.4 72.5 11 332<br />

Virtanen (2005) 1.3 7.8 7710 83.9 3.9 4.2 8.9 1611<br />

norm. concent.)<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

Co concentration [mg/kg]<br />

0.1 1 10 100<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Fig. 11. Cobalt concentrations in peat at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Co.<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

1<br />

0<br />

10 100 1000<br />

M1<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Fig. 12. Copper concentrations in peat at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Cu.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Cu concentration [mg/kg]<br />

1000 10000 100000<br />

Fig. 13. Iron concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Fe.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

Fe concentration [mg/kg]<br />

Mn concentration [mg/kg]<br />

1<br />

0<br />

10 100 1000<br />

50<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Fig. 14. Manganese concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Mn.<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

19

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

Manganese concentrations were high in the uppermost<br />

sur<strong>fi</strong>cial peat at all study sites (Fig. 14).<br />

Manganese was enriched at the peatland surface.<br />

However, the minimum manganese concentration<br />

at all study sites was recorded at a depth <strong>of</strong> 20 cm.<br />

Below the surface, the manganese concentration<br />

remained relatively constant with depth at study<br />

site M1, while at M3 it increased towards the bottom<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peat layer. At study site M2, the manganese<br />

concentration increased from the surface<br />

to a depth <strong>of</strong> 80 cm, below which the concentration<br />

steadily decreased towards the bottom.<br />

The nickel concentration increased towards the<br />

bottom at all study sites, the largest increase being<br />

recorded at study site M2 (Fig. 15). Nickel was<br />

enriched in the bottom peatland layers.<br />

The lead concentration was greatest near the<br />

surface <strong>of</strong> the peat layer at all study sites (Fig. 16).<br />

20<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Lead was enriched at the peatland surface. Lead<br />

concentrations decreased downwards to a depth<br />

<strong>of</strong> less than a metre, after which they increased<br />

again. The average lead concentration was the<br />

same at each study site, which reflects the concentrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> bedrock and soil (Tables 1–3). The Talvivaara<br />

black schists tend not be enriched in Pb<br />

when compared to the average mica schists, which<br />

could also indicate that lead effectively binds to<br />

humic substances and is not easily transported<br />

through the soil.<br />

Uranium concentrations in the peat increased<br />

towards the bottom, with the exception <strong>of</strong> study<br />

site M3 (Fig. 17). At study site M3 the uranium<br />

concentration began to increase below a depth<br />

<strong>of</strong> 70 cm. The maximum uranium concentrations<br />

were recorded close to the soil.<br />

Except near the peat surface, the concentra-<br />

Ni concentration [mg/kg]<br />

1 10 100 1000<br />

Fig. 15. Nickel concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Ni.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0.1<br />

0<br />

1 10 100<br />

M1<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Pb concentration [mg/kg]<br />

Fig. 16. Lead concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Pb.<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

M2<br />

M3

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0.1 1 10<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

U concentration [mg/kg]<br />

Fig. 17. Uranium concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for U.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

tion <strong>of</strong> zinc increased as a function <strong>of</strong> depth at<br />

the black schist study sites M2 and M3 (Fig. 18).<br />

The zinc concentration decreased with depth at<br />

the mica schist study site M1, at least to a depth<br />

<strong>of</strong> one and a half metres, after which the concentration<br />

increased again. The average zinc content<br />

at study site M2 was 168 times greater than at M1<br />

(Table 7).<br />

The acidity <strong>of</strong> the peat layers decreased downwards,<br />

as seen at M1 and M3 (Fig. 18). At study<br />

site M2, acidity decreased down to a depth <strong>of</strong><br />

about 50 cm, after which there was a sharp reversal<br />

in trend. Because the surrounding bedrock was<br />

sulphide-rich, pH values were also anomalous at<br />

M2. The pH <strong>of</strong> peat is usually lowest in the surface<br />

layer (regional average 3.1–3.7) (Virtanen et<br />

al. 2003). The pH <strong>of</strong> the surface peat is dependent<br />

Zn concentration [mg/kg]<br />

1 10 100 1000 10000<br />

Fig. 18. Zinc concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for Zn.<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

upon the availability <strong>of</strong> hydrogen ions in Sphagnum<br />

peat, in that free hydrogen ions are produced<br />

by the cation exchange in the Sphagnum peat and<br />

organic acids are released by the aerobic decomposition<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sphagnum (Shotyk 1988).<br />

The pH value increases with depth in the peat<br />

layer. A high sulphur concentration causes a lowering<br />

<strong>of</strong> pH and an increase in conductivity (see<br />

Figs. 19–20). The average pH values for bottom<br />

peat layer in Finland range from 4.5 to 4.9 (Virtanen<br />

et al. 2003). At study site M1, pH levels<br />

were closest to the Finnish average, whereas the<br />

largest differences were found at the black schist<br />

study site M2; at this site the pH <strong>of</strong> the bottom<br />

peat layer (2.8–3.7) was the same or lower than<br />

the Finnish average values for surface peat.<br />

The sulphide concentration <strong>of</strong> study site M1<br />

21

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

22<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

2.5<br />

0<br />

3 3.5 4 4.5 5<br />

M1<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Fig. 19. Acidity (pH value) at study sites M1, M2 and M3.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

pH value<br />

1000<br />

0<br />

10000 100000 1000000<br />

M1<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

S concentration [mg/kg]<br />

Fig. 20. Sulphur concentrations at study sites M1, M2 and M3. The scale is logarithmic for S.<br />

was lower than at M3 and markedly less than at<br />

M2 (Fig. 20). Sulphur concentrations increased as<br />

a function <strong>of</strong> depth at all the study sites, most notably<br />

at M2 (Fig. 20). The increasing effect <strong>of</strong> the<br />

underlying soil was seen at the bottom <strong>of</strong> study<br />

sites M1 and M2. Essentially, sulphur in peat is<br />

transported from the underlying soil via plant<br />

roots. Sulphur is also likely to have risen into the<br />

peat layer by capillary flow, and then to have become<br />

bound to the peat. The high sulphur concentrations<br />

appear to be influenced most strongly<br />

by the bedrock in the black schist areas, while at<br />

study site M2, acidic drainage has also contributed<br />

signi<strong>fi</strong>cantly to the elevated S concentrations.<br />

The highest average sulphur concentrations reported<br />

for Finnish peatlands are from the black<br />

schist areas <strong>of</strong> North Karelia (Herranen 2010),<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

which together account for approximately a third<br />

<strong>of</strong> the peatlands with the highest average sulphur<br />

concentrations in Finland. Virtanen and Lerssi<br />

(2006) observed that some element concentrations<br />

in peat are typically elevated in areas underlain<br />

by black schists; sulphur concentrations for<br />

example, may be up to 50–100 times greater than<br />

background levels.<br />

At study sites M1 and M3 the carbon content<br />

remained relatively constant with increasing<br />

depth. However, at study site M2, the carbon content<br />

decreased with depth, along with a coincident<br />

increase in ash content (Fig. 21).<br />

At the black schist study sites M2 and M3,<br />

the water content in peat increased from the surface<br />

down to a depth <strong>of</strong> about 0.6 m, mainly due<br />

to peatland drainage activities which had been

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Fig. 21. Carbon content at study sites M1, M2 and M3.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

particularly intensive in the Talvivaara area in<br />

the <strong>196</strong>0s (Fig. 22). The water table in the peat<br />

shows slight seasonal variations but was located<br />

at a depth <strong>of</strong> about half a metre at each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

study sites. Below this depth, the water content<br />

decreased most markedly at study site M2. Acidic<br />

waters had also displaced the peat pore waters;<br />

this was particulary evident at study site M2,<br />

where the ash content was high and the water content<br />

low (Table 2). There was a distinct correlation<br />

between the water content and the concentrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> analysed metals.<br />

At study site M1, the ash content <strong>of</strong> the peat<br />

layer was representative <strong>of</strong> the average ash content<br />

<strong>of</strong> peatlands in Finland, but the ash content<br />

was anomalously high at study site M2 (Fig. 23).<br />

According to Mäkilä (1994), the average ash con-<br />

C content [%]<br />

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70<br />

79 81<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Fig. 22. Water content at study sites M1, M2 and M3.<br />

Water content [%]<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

83 85 87 89 91 93<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

tents <strong>of</strong> different peat types are 4.0% in Sphagnum-<br />

Carex peat, 3.8% in Carex peat, 3.4% in Carex-<br />

Sphagnum peat and 1.6% in Sphagnum peat. The<br />

degree <strong>of</strong> humi<strong>fi</strong>cation <strong>of</strong> peat also affects the ash<br />

content, although its effect is smaller than that<br />

due to the peat type. The elements contained in<br />

ash and their various resultant compounds constitute<br />

the inorganic component <strong>of</strong> the chemical<br />

composition <strong>of</strong> peat. Peat ash is derived from<br />

peatland vegetation (primary ash) and surrounding<br />

mineral matter (secondary ash). Material is<br />

classi<strong>fi</strong>ed as peat when the proportion <strong>of</strong> organic<br />

dry mass is at least 75%. At study site M2 in particular,<br />

the ash content was very high, so that with<br />

the exception <strong>of</strong> the peat surface the ash content<br />

exceeded the 25% threshold.<br />

Electrical conductivity increased from top to<br />

23

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

bottom at the black schist study sites M2 and<br />

M3 (Fig. 24). At study site M1, conductivity de-<br />

24<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

0 5 10 15<br />

Fig. 23. Ash content at study sites M1, M2 and M3.<br />

Depth [cm]<br />

0<br />

50<br />

100<br />

150<br />

200<br />

250<br />

Figure 25 presents statistically signi<strong>fi</strong>cant correlations<br />

between each <strong>of</strong> the parameters analysed<br />

at study sites M1, M2 and M3, computed using<br />

the Spearman method. Dark blue and light blue<br />

colours indicate a negative correlations with signi<strong>fi</strong>cance<br />

levels <strong>of</strong>

M1<br />

Co<br />

Cu<br />

Ni<br />

Pb<br />

U<br />

Fe<br />

Mn<br />

S<br />

Zn<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

DryDensity<br />

Ash<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

Depth<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

M3 Co<br />

Co<br />

Cu<br />

Ni<br />

Pb<br />

U<br />

Fe<br />

Mn<br />

S<br />

Zn<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

DryDensity<br />

Ash<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

Depth<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Co<br />

Cu<br />

Ni<br />

Pb<br />

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

U<br />

Fe<br />

Cu<br />

Ni<br />

Pb<br />

U<br />

Fe<br />

Mn<br />

Mn<br />

S<br />

S<br />

Zn<br />

Zn<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

DryDensity<br />

Ash<br />

DryDensity<br />

Ash<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

Depth<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

tivity correlate with other analysed elements and<br />

peat properties.<br />

At study site M1, iron correlated most strongly<br />

with ash content, lead and zinc (Fig. 26). Iron<br />

showed a strong positive correlation with Ni, S,<br />

Zn, U, Co and conductivity at study site M2. At<br />

study site M3, iron had a strongly positive correlation<br />

with conductivity, manganese and sulphur,<br />

and a strongly negative correlation with cobalt<br />

and lead.<br />

At study site M1, uranium showed a strongly<br />

positive correlation with copper, sulphur, nickel<br />

and pH and a negative correlation with conductivity<br />

(Fig. 27). Uranium had a strongly positive<br />

correlation with Cu, Zn, Fe, Ni, conductivity, S<br />

and Co at study site M2 and a negative correlation<br />

with Mn. At study site M3, uranium was<br />

strongly correlated with Co.<br />

At study site M1, a positive correlation was ob-<br />

M2 Co<br />

Co<br />

Cu<br />

Ni<br />

Pb<br />

U<br />

Fe<br />

Mn<br />

S<br />

Zn<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

DryDensity<br />

Ash<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

Depth<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Cu<br />

Ni<br />

Pb<br />

U<br />

Fe<br />

Mn<br />

S<br />

Zn<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

DryDensity<br />

Ash<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

Depth<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).<br />

Neg. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />

Neg. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).<br />

Fig. 25. Statistically signi<strong>fi</strong>cant correlations between the studied properties at study sites M1, M2 and M3.<br />

Depth<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

served between sulphur and copper, pH, uranium<br />

and nickel, but a signi<strong>fi</strong>cant negative correlation<br />

was found between sulphur and conductivity (Fig.<br />

28). Signi<strong>fi</strong>cant positive correlations between sulphur<br />

and conductivity, nickel, iron and zinc were<br />

recorded at the black schist study site M2 (Figs.<br />

24 and 28). It is probable that the iron and the<br />

sulphur have combined to form an iron-sulphur<br />

compound in the peat (Virtanen & Lerssi 2006).<br />

Iron-sulphur compounds in peat appear to reduce<br />

the pH <strong>of</strong> peat when present at high concentrations.<br />

This effect becomes apparent when the<br />

contents <strong>of</strong> both iron and sulphur exceed 1% <strong>of</strong><br />

dry mass (Virtanen & Lerssi 2006). In the present<br />

data, an effect on pH levels is discernible at study<br />

site M2 when the contents <strong>of</strong> both iron and sulphur<br />

were approximately 20 000 mg/kg or 2 000 g/<br />

peatland-m 3 (Tables 2 and 5). At the black schist<br />

study site M3, a signi<strong>fi</strong>cant positive correlation<br />

25

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

26<br />

Fe<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

WaterCont.<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

U<br />

Cu<br />

S<br />

Co<br />

C<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

Co<br />

Pb<br />

WaterCont.<br />

pH<br />

Mn<br />

Pb<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

DryDensity<br />

C<br />

WaterCont.<br />

Cu<br />

DryDensity<br />

U<br />

Ni<br />

Ash<br />

Zn<br />

Cu<br />

pH<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).<br />

Neg. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />

Neg. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).<br />

Depth<br />

DryDensity<br />

Mn<br />

pH<br />

Ni<br />

Zn<br />

Pb<br />

Ash<br />

Fe<br />

Ash<br />

Co<br />

U<br />

Zn<br />

S<br />

Conductivity<br />

Ni<br />

Depth<br />

Fe<br />

S<br />

Depth<br />

Mn<br />

Conductivity<br />

Fe<br />

Fig. 26. The statistically most signi<strong>fi</strong>cant correlations between iron and other measured variables at study sites M1, M2 and<br />

M3.

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

High pre-mining metal concentrations and conductivity in peat around the Talvivaara nickel deposit, eastern Finland<br />

U<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

C<br />

Conductivity<br />

WaterCont.<br />

Zn<br />

Co<br />

WaterCont.<br />

Mn<br />

pH<br />

WaterCont.<br />

pH<br />

S<br />

Depth<br />

Co<br />

Mn<br />

C<br />

Zn<br />

Conductivity<br />

Fe<br />

M3<br />

Fe<br />

Mn<br />

Pb<br />

C<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Ash<br />

DryDensity<br />

pH<br />

Ni<br />

Depth<br />

Pb<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Ash<br />

DryDensity<br />

Co<br />

S<br />

Conductivity<br />

Ni<br />

Fe<br />

Depth<br />

Zn<br />

Cu<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Ni<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).<br />

Neg. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />

Neg. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).<br />

S<br />

Cu<br />

Ash<br />

Pb<br />

Cu<br />

DryDensity<br />

Fig. 27. The statistically most signi<strong>fi</strong>cant correlations between uranium and other investigated parameters at study sites M1,<br />

M2 and M3.<br />

U<br />

U<br />

U<br />

27

<strong>Geologian</strong> <strong>tutkimuskeskus</strong>, Tutkimusraportti <strong>196</strong> – Geological Survey <strong>of</strong> Finland, <strong>Report</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Investigation</strong> <strong>196</strong>, 2012<br />

Markku Mäkilä, Kirsti Loukola-Ruskeeniemi and Heikki Säävuori<br />

28<br />

S<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

Spearman’s correlation coef<strong>fi</strong>cient<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

1.0<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-0.2<br />

-0.4<br />

-0.6<br />

-0.8<br />

-1.0<br />

Conductivity<br />

Zn<br />

WaterCont.<br />

Mn<br />

Co<br />

DryDensity<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Pb<br />

Fe<br />

C<br />

C<br />

Pb<br />

M1<br />

M2<br />

M3<br />

WaterCont.<br />

Mn<br />

pH<br />

Pb<br />

DryDensity<br />

Co<br />

U<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Cu<br />

Ash<br />

Ni<br />

C<br />

Humi<strong>fi</strong>cation<br />

Cu<br />

DryDensity<br />

Co<br />

Ash<br />

U<br />

Ash<br />

Ni<br />

Pos. correlation is signi<strong>fi</strong>cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).<br />