View/Open - Aaltodoc

View/Open - Aaltodoc

View/Open - Aaltodoc

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

on the environmental performance of a<br />

building (Hoes, Hensen et al. 2009).<br />

The influence of the occupancy rate of a<br />

building on its ecological sustainability<br />

is neglected however. As academic<br />

workplace utilization generally lies between<br />

twenty-five and thirty percent (Harrison<br />

2010), it is to be expected that this has an<br />

impact on the sustainability of the situation.<br />

Both in economical, and ecological terms.<br />

This low occupancy results in inefficient use,<br />

and diffuses the actual spatial demand.<br />

Harrison (2010) states that because of the<br />

low use-rate of this particular part of our built<br />

environment, enhanced by the changing<br />

culture in learning, traditional categories<br />

of space become less meaningful. People<br />

have different daily rhythms. This causes<br />

some people to be more active, and<br />

willing to work or study in evenings and<br />

weekends, while others prefer to work<br />

during office hours. When spaces, and their<br />

supporting operations can adjust to such<br />

differences, their use could be optimized.<br />

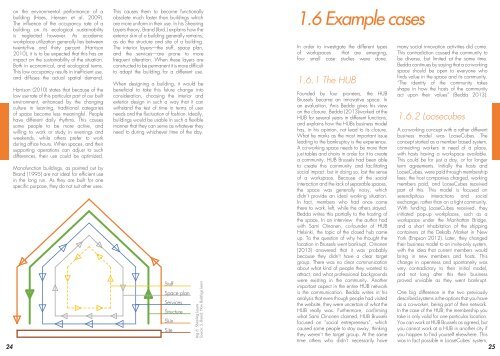

Monofunction buildings, as pointed out by<br />

Brand (1995) are not ideal for efficient use<br />

in the long run. As they are built for one<br />

specific purpose, they do not suit other uses.<br />

This causes them to become functionally<br />

obsolete much faster than buildings which<br />

are more uniform in their use. In his Shearing<br />

Layers theory, Brand (Ibid.) explains how the<br />

exterior skin of a building generally remains,<br />

as do the structure and site of a building.<br />

The interior layers—the stuff, space plan,<br />

and the services—are prone to more<br />

frequent alteration. When these layers are<br />

constructed to be permanent it is more difficult<br />

to adapt the building for a different use.<br />

When designing a building, it would be<br />

beneficial to take this future change into<br />

consideration, choosing the interior and<br />

exterior design in such a way that it can<br />

withstand the test of time in terms of user<br />

needs and the fluctuation of fashion. Ideally,<br />

buildings would be usable in such a flexible<br />

manner that they can serve as whatever they<br />

need to during whichever time of the day.<br />

Img 6: Shearling Layers<br />

Source: S. Brand; How Buildings Learn<br />

1.6 Example cases<br />

In order to investigate the different types<br />

of workspaces that are emerging,<br />

four small case studies were done.<br />

1.6.1 The HUB<br />

Founded by four pioneers, the HUB<br />

Brussels became an innovative space. In<br />

an evaluation, Anis Bedda gives his view<br />

on the closure. Bedda (2013)worked at the<br />

HUB for several years in different functions,<br />

and explains how the HUBs business model<br />

has, in his opinion, not lead to its closure.<br />

What he marks as the most important issue<br />

leading to the bankruptcy is the experience.<br />

A co-working space needs to be more than<br />

just tables and chairs in order for it to create<br />

a community. HUB Brussels had been able<br />

to create this community and facilitating<br />

social impact, but in doing so, lost the sense<br />

of a workspace. Because of the social<br />

interaction and the lack of separable spaces,<br />

the space was generally noisy, which<br />

didn’t provide an ideal working situation.<br />

In fact, members who had once come<br />

there to work, left, while the others stayed.<br />

Bedda writes this partially to the hosting of<br />

the space. In an interview the author had<br />

with Sami Oinonen, co-founder of HUB<br />

Helsinki, the topic of the closed hub came<br />

up. To the question of why he thought the<br />

location in Brussels went bankrupt, Oinonen<br />

(2013) answered that it was probably<br />

because they didn’t have a clear target<br />

group. There was no clear communication<br />

about what kind of people they wanted to<br />

attract, and what professional backgrounds<br />

were existing in the community. Another<br />

important aspect in the entire HUB network<br />

is the communication. Bedda writes in his<br />

analysis that even though people had visited<br />

the website, they were uncertain of what the<br />

HUB really was. Furthermore, confirming<br />

what Sami Oinonen claimed, HUB Brussels<br />

focused on “social entrepreneurs”, which<br />

caused some people to stay away, thinking<br />

they weren’t the target group. At the same<br />

time others who didn’t necessarily have<br />

many social innovation activities did come.<br />

This contradiction caused the community to<br />

be diverse, but limited at the same time.<br />

Bedda continues by saying that a co-working<br />

space should be open to everyone who<br />

finds value in the space and its community.<br />

“The identity of the community takes<br />

shape in how the hosts of the community<br />

act upon their values” (Bedda 2013).<br />

1.6.2 Loosecubes<br />

A co-working concept with a rather different<br />

business model was LooseCubes. The<br />

concept started as a member based system,<br />

connecting workers in need of a place,<br />

with hosts having a workspace available.<br />

This could be for just a day, or for longer<br />

term agreements. Initially the hosts and<br />

LooseCubes, were paid through membership<br />

fees: the host companies charged, working<br />

members paid, and LooseCubes received<br />

part of this. This model is focused on<br />

serendipitous interactions and social<br />

exchange, rather than on a tight community.<br />

With funding LooseCubes received, they<br />

initiated pop-up workplaces, such as a<br />

workspace under the Manhattan Bridge,<br />

and a short inhabitation of the shipping<br />

containers at the Dekalb Market in New<br />

York (Empson 2012). Later, they changed<br />

their business model to an invite-only system,<br />

with the idea that current members would<br />

bring in new members and hosts. This<br />

change in openness and spontaneity was<br />

very contradictory to their initial model,<br />

and not long after this their business<br />

proved unviable as they went bankrupt.<br />

Stuff<br />

Space plan<br />

One big difference in the two previously<br />

described systems is the options that you have<br />

Services<br />

as a co-worker, being part of their network.<br />

Structure<br />

In the case of the HUB, the membership you<br />

take is only valid for one particular location.<br />

Skin<br />

You can work at HUB Brussels as agreed, but<br />

Site<br />

you cannot work at a HUB in another city if<br />

you happen to find yourself elsewhere. This<br />

was in fact possible in LooseCubes’ system,<br />

24 25