Pacific Islands Environment Outlook - UNEP

Pacific Islands Environment Outlook - UNEP

Pacific Islands Environment Outlook - UNEP

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ATMOSPHERE 19<br />

The findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on<br />

Climate Change (IPCC) (Houghton et al. 1996) confirm<br />

that ‘the balance of evidence suggests a discernible<br />

human influence on global climate’ and that ‘more<br />

convincing recent evidence for the attribution of a<br />

human effect on climate is emerging…’, which is<br />

unlikely to be ‘a result of natural internal variability’<br />

(Watson, Zinyowera and Moss 1998). This is of on-going<br />

and particular concern to <strong>Pacific</strong> island governments<br />

and peoples, most of whose lives are entirely coastal in<br />

nature (SPREP 1993a).<br />

The three greatest anticipated consequences of any<br />

global warming are expected to be sea-level rise, an<br />

increase in climate-related natural disasters (storms,<br />

floods and droughts) and disruption to agriculture due to<br />

changes in temperature, rainfall and winds. The IPCC has<br />

noted that the ‘best estimate’ of sea-level rise from the<br />

present to the year 2100 is 50 cm, with a range for all<br />

scenarios of 15–95 cm by the end of the century.<br />

In the <strong>Pacific</strong>, areas under threat have been identified<br />

as marine ecosystems, coastal systems, tourism, human<br />

settlement and infrastructure (IPCC 1998). There is<br />

growing evidence that the nature of impacts in this<br />

region is indicative of a changing climate. The region has<br />

lost atolls due to rising seas and has experienced more<br />

extreme events and weather, coupled with El Niño. The<br />

results have included water shortages and drought in<br />

PNG, Marshall <strong>Islands</strong>, FSM, American Samoa, Samoa<br />

and Fiji, and floods in New Zealand. Data gathered by<br />

New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and<br />

Atmospheric Research (NIWA) also show a general<br />

change in the South <strong>Pacific</strong> climate from the mid-1970s:<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

Kiribati, northern Cook <strong>Islands</strong>, Tokelau and northern<br />

parts of French Polynesia have become wetter;<br />

New Caledonia, Fiji and Tonga have become drier;<br />

Samoa, eastern Kiribati, Tokelau and northeast<br />

French Polynesia have become warmer and cloudier<br />

and the difference between daytime and night-time<br />

temperatures has decreased;<br />

New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, southern Cook <strong>Islands</strong><br />

and southwest French Polynesia have become<br />

warmer and sunnier;<br />

Western Kiribati and Tuvalu have become sunnier.<br />

Cyclones are a common feature, with some countries<br />

experiencing them almost each year. Table 1.4 shows<br />

the level of risk to PICs of natural disasters such as<br />

cyclones. With the likelihood that the frequency and<br />

intensity of weather extremes will increase global<br />

warming, the region’s ability to develop a strong<br />

productive base for sustainable development is<br />

jeopardized. Tokelau had had only three major storms<br />

since 1846 until two cyclones (Tusi and Ofa) struck in<br />

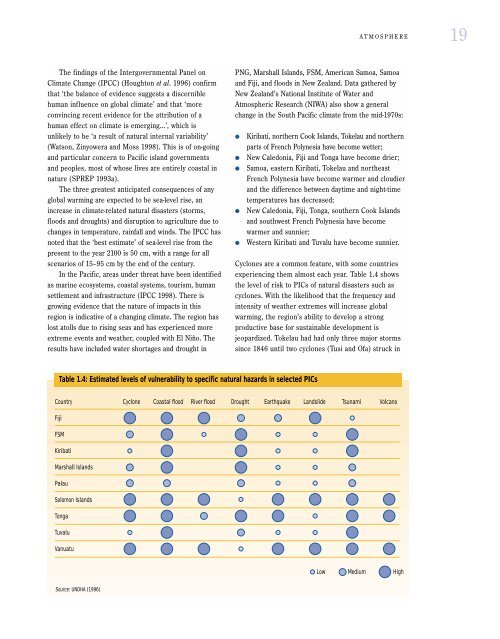

Table 1.4: Estimated levels of vulnerability to specific natural hazards in selected PICs<br />

Country<br />

Cyclone Coastal flood River flood Drought Earthquake Landslide Tsunami Volcano<br />

Fiji<br />

FSM<br />

Kiribati<br />

Marshall <strong>Islands</strong><br />

Palau<br />

Solomon <strong>Islands</strong><br />

Tonga<br />

Tuvalu<br />

Vanuatu<br />

Low Medium High<br />

Source: UNDHA (1996)