Pacific Islands Environment Outlook - UNEP

Pacific Islands Environment Outlook - UNEP

Pacific Islands Environment Outlook - UNEP

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

27<br />

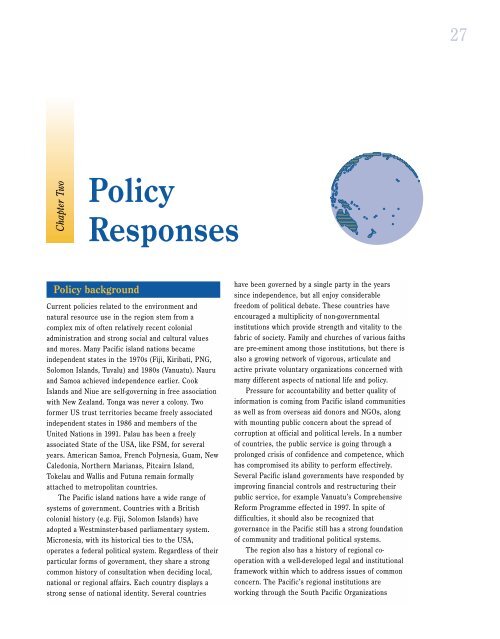

Chapter Two<br />

Policy<br />

Responses<br />

Policy background<br />

Current policies related to the environment and<br />

natural resource use in the region stem from a<br />

complex mix of often relatively recent colonial<br />

administration and strong social and cultural values<br />

and mores. Many <strong>Pacific</strong> island nations became<br />

independent states in the 1970s (Fiji, Kiribati, PNG,<br />

Solomon <strong>Islands</strong>, Tuvalu) and 1980s (Vanuatu). Nauru<br />

and Samoa achieved independence earlier. Cook<br />

<strong>Islands</strong> and Niue are self-governing in free association<br />

with New Zealand. Tonga was never a colony. Two<br />

former US trust territories became freely associated<br />

independent states in 1986 and members of the<br />

United Nations in 1991. Palau has been a freely<br />

associated State of the USA, like FSM, for several<br />

years. American Samoa, French Polynesia, Guam, New<br />

Caledonia, Northern Marianas, Pitcairn Island,<br />

Tokelau and Wallis and Futuna remain formally<br />

attached to metropolitan countries.<br />

The <strong>Pacific</strong> island nations have a wide range of<br />

systems of government. Countries with a British<br />

colonial history (e.g. Fiji, Solomon <strong>Islands</strong>) have<br />

adopted a Westminster-based parliamentary system.<br />

Micronesia, with its historical ties to the USA,<br />

operates a federal political system. Regardless of their<br />

particular forms of government, they share a strong<br />

common history of consultation when deciding local,<br />

national or regional affairs. Each country displays a<br />

strong sense of national identity. Several countries<br />

have been governed by a single party in the years<br />

since independence, but all enjoy considerable<br />

freedom of political debate. These countries have<br />

encouraged a multiplicity of non-governmental<br />

institutions which provide strength and vitality to the<br />

fabric of society. Family and churches of various faiths<br />

are pre-eminent among those institutions, but there is<br />

also a growing network of vigorous, articulate and<br />

active private voluntary organizations concerned with<br />

many different aspects of national life and policy.<br />

Pressure for accountability and better quality of<br />

information is coming from <strong>Pacific</strong> island communities<br />

as well as from overseas aid donors and NGOs, along<br />

with mounting public concern about the spread of<br />

corruption at official and political levels. In a number<br />

of countries, the public service is going through a<br />

prolonged crisis of confidence and competence, which<br />

has compromised its ability to perform effectively.<br />

Several <strong>Pacific</strong> island governments have responded by<br />

improving financial controls and restructuring their<br />

public service, for example Vanuatu’s Comprehensive<br />

Reform Programme effected in 1997. In spite of<br />

difficulties, it should also be recognized that<br />

governance in the <strong>Pacific</strong> still has a strong foundation<br />

of community and traditional political systems.<br />

The region also has a history of regional cooperation<br />

with a well-developed legal and institutional<br />

framework within which to address issues of common<br />

concern. The <strong>Pacific</strong>’s regional institutions are<br />

working through the South <strong>Pacific</strong> Organizations