Neolithic and Bronze Age Landscapes of North Mayo: Report 2011

Neolithic and Bronze Age Landscapes of North Mayo: Report 2011

Neolithic and Bronze Age Landscapes of North Mayo: Report 2011

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

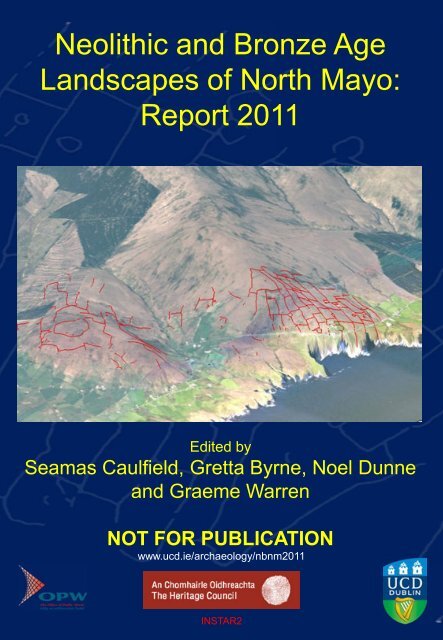

<strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

L<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>:<br />

<strong>Report</strong> <strong>2011</strong><br />

Edited by<br />

Seamas Caulfield, Gretta Byrne, Noel Dunne<br />

<strong>and</strong> Graeme Warren<br />

NOT FOR PUBLICATION<br />

www.ucd.ie/archaeology/nbnm<strong>2011</strong><br />

INSTAR2

<strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> L<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>: <strong>2011</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Seamas Caulfield, Gretta Byrne, Noel Dunne <strong>and</strong><br />

Graeme Warren (eds)<br />

And reports from<br />

Meriel McClatchie, Emmett O’Keeffe <strong>and</strong> Helen Roche<br />

Not for public circulation<br />

December <strong>2011</strong><br />

i

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Introduction ................................................................................................... 1<br />

Work Packages One <strong>and</strong> Two ................................................................................................................. 2<br />

Work Package Three ............................................................................................................................... 3<br />

Part One: Specialist <strong>Report</strong>s<br />

Creating Digital Archaeological L<strong>and</strong>scapes: An archaeological GIS for the<br />

NBNM project, by Emmett O’Keeffe. ............................................................. 5<br />

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5<br />

Aims ........................................................................................................................................................ 5<br />

Datasets .................................................................................................................................................. 6<br />

Results ..................................................................................................................................................... 7<br />

Outputs ................................................................................................................................................. 12<br />

Radiocarbon Dating ..................................................................................... 13<br />

Charcoal analysis from <strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>,<br />

by Lorna O’Donnell ...................................................................................... 21<br />

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Sampling strategy.................................................................................................................................. 21<br />

Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Results ................................................................................................................................................... 23<br />

Glenulra enclosure E24 Middle <strong>Neolithic</strong> ............................................................................................. 24<br />

Glenulra Scatter 92E140 Middle <strong>Neolithic</strong> ............................................................................................ 25<br />

Céide Visitor Centre (E494) Late <strong>Neolithic</strong>/Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> ............................................................... 26<br />

Belderg Beg E109 Early/Middle <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> ......................................................................................... 28<br />

Rathlackan E580 Early/Middle <strong>Neolithic</strong> to Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. ............................................................. 36<br />

ii

Discussion.............................................................................................................................................. 41<br />

Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 46<br />

Acknowledgements:.............................................................................................................................. 46<br />

References ............................................................................................................................................ 47<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> non-wood plant macro-remains, by Meriel McClatchie .............. 84<br />

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 84<br />

Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 84<br />

Plant macro-remains recorded ............................................................................................................. 84<br />

Discussion.............................................................................................................................................. 89<br />

Recommendation for retention/deaccessioning .................................................................................. 92<br />

Conclusions ........................................................................................................................................... 92<br />

References ............................................................................................................................................ 93<br />

Part Two: Draft Chapters<br />

Soils <strong>and</strong> Geology, by Graeme Warren ......................................................... 97<br />

Geology ................................................................................................................................................. 97<br />

Deglaciation <strong>and</strong> sea level change ...................................................................................................... 100<br />

Sea level .................................................................................................... 101<br />

River processes ................................................................................................................................... 102<br />

Soils ..................................................................................................................................................... 102<br />

References .......................................................................................................................................... 105<br />

History <strong>of</strong> Archaeological <strong>and</strong> Related Research in <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>, by Seamas<br />

Caulfield .................................................................................................... 106<br />

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 106<br />

Archaeological Research ..................................................................................................................... 107<br />

The Belderrig Valley Research: Belderg Beg Excavations. .................................................................. 110<br />

iii

Scientific Research associated with the Archaeological Projects. ...................................................... 112<br />

The <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong> Research <strong>and</strong> the Public .......................................................................................... 113<br />

New Research <strong>and</strong> Researchers .......................................................................................................... 115<br />

Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 116<br />

Probed Surveys: Erris, Céide Fields <strong>and</strong> Belderg More, by Seamas Caulfield<br />

.................................................................................................................. 117<br />

Traditional Turf Cutting in <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong> .............................................................................................. 117<br />

The Erris Survey................................................................................................................................... 118<br />

The Céide Fields Survey ...................................................................................................................... 119<br />

Belderrig Valley: The Belderg More Survey ....................................................................................... 121<br />

Survey on the Glenamoy – Bartnatra Peninsula, by Noel Dunne ................ 123<br />

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 123<br />

Study Area ........................................................................................................................................... 123<br />

Megalithic tombs, cists <strong>and</strong> stone circles ........................................................................................... 126<br />

Prehistoric boundaries ........................................................................................................................ 130<br />

Prehistoric settlements ....................................................................................................................... 137<br />

Overall prehistoric settlement areas <strong>and</strong> voids .................................................................................. 139<br />

Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 142<br />

Survey from Ballinglen to Rathfran Bay, by Gretta Byrne ........................... 143<br />

Research Outline <strong>and</strong> Methodology ................................................................................................... 143<br />

Field Walls ........................................................................................................................................... 144<br />

Associated Structures ......................................................................................................................... 149<br />

Discussion............................................................................................................................................ 151<br />

References .......................................................................................................................................... 154<br />

iv

Acknowledgments<br />

This report is the product <strong>of</strong> many years <strong>of</strong> work, from many different people, far too numerous to<br />

name here. The projects summarised by the NBNM project here, over the years, have received<br />

funding from many different sources – indeed, the projects summarised <strong>of</strong>fer in many senses a<br />

history <strong>of</strong> Irish archaeology <strong>and</strong> the availability <strong>of</strong> funding, from emergency labour schemes through<br />

to varied research grants. Where specific funding has been provided for particular projects these are<br />

discussed in text. The contribution <strong>of</strong> volunteer labour, especially that <strong>of</strong> students, to the success <strong>of</strong><br />

the projects over the long term should also be noted.<br />

The <strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> L<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong> project has been supported by INSTAR <strong>and</strong><br />

INSTAR2 in 2009-<strong>2011</strong>, following a pilot in 2008 supported by the Heritage Council’s unpublished<br />

excavations scheme. We are extremely grateful for this support, without which it would not have<br />

been possible to develop the project <strong>and</strong> to be as close to final publication <strong>of</strong> this material as we<br />

now are.<br />

v

Introduction<br />

This report reviews the work carried out as part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> L<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Mayo</strong> (NBNM) project in <strong>2011</strong>. The NBNM project will bring to final publication critically important<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> archaeology <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> County <strong>Mayo</strong>, specifically Caulfield’s<br />

survey <strong>and</strong> excavation in Belderrig; survey/excavation by varied parties at ‘Céide Fields’; Byrne’s<br />

survey <strong>and</strong> excavation at Rathlackan <strong>and</strong> Dunne’s survey work in Pollatomas.<br />

The buried l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> the Céide Fields are iconic for Irish archaeology, <strong>of</strong> international<br />

significance <strong>and</strong> were included on the Irish tentative list <strong>of</strong> World Heritage Sites. According to this<br />

designation the Céide Fields <strong>and</strong> associated l<strong>and</strong>scapes have ‘outst<strong>and</strong>ing universal value’:<br />

“The significance <strong>of</strong> the Céide Fields lies in the fact that along with their associated megalithic<br />

monuments <strong>and</strong> dwelling structures they provide a unique farmed l<strong>and</strong>scape from <strong>Neolithic</strong> times.<br />

Not only are they "an outst<strong>and</strong>ing example" but they are the outst<strong>and</strong>ing example <strong>of</strong> human<br />

settlement, l<strong>and</strong>‐use <strong>and</strong> interaction with environment in <strong>Neolithic</strong> times. The first adoption <strong>of</strong><br />

farming occurred at different times throughout the world. Nowhere else is there such extensive<br />

physical remains <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Neolithic</strong> farmed l<strong>and</strong>scape surviving from this significant period in prehistory.”<br />

(http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5524/: original emphasis)<br />

The current project extends the success <strong>of</strong> the Céide Fields work in outreach <strong>and</strong> attempts to<br />

remedy the lack <strong>of</strong> full academic publication <strong>of</strong> this material, which is recognized as <strong>of</strong> international<br />

significance. Our initial proposed model for the project has been a three year project resulting in:<br />

- an academic monograph detailing the results <strong>of</strong> survey, excavation <strong>and</strong> further specialist work<br />

carried out in the region<br />

- a book targeted at the general public outlining the nature, significance <strong>and</strong> future <strong>of</strong> these<br />

archaeological l<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

Two phases <strong>of</strong> work with INSTAR funding have been completed to date following a preliminary<br />

phase in 2008, supported by the Heritage Council’s unpublished excavations grant; in 2009 registers<br />

for artefacts <strong>and</strong> samples <strong>and</strong> stratigraphic reports were generated. In 2010 specialist analyses <strong>of</strong><br />

artefacts <strong>and</strong> assessments <strong>of</strong> environmental data were undertaken, along with some illustration <strong>of</strong><br />

artefacts <strong>and</strong> C14 dating. Digitising <strong>of</strong> extant plans was undertaken <strong>and</strong> a robust spatial framework<br />

provided for same. In <strong>2011</strong> we made a minor modification to our proposed timeline, recognising the<br />

considerable complexity <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the sites. We proposed to complete substantial components <strong>of</strong><br />

the final volume, including full reports on the excavations at <strong>and</strong> near the main part <strong>of</strong> the Céide<br />

Fields complex – the area immediately surrounding the Céide Fields Visitor Centre (‘Céide Hil). In<br />

2012 we will complete the reports for Belderg Beg <strong>and</strong> Rathlackan <strong>and</strong> finalise synthesis <strong>and</strong><br />

interpretation. We are providing two reports for INSTAR. This document collates all draft texts <strong>and</strong><br />

reports produced this year – it is not intended for public consumption. It is accompanied by a<br />

substantial report on the excavations at Céide Hill which can be published on line.<br />

1

Fe<br />

br<br />

ua<br />

ry<br />

M<br />

arc<br />

h<br />

April May June July<br />

Aug<br />

ust<br />

Sept Oct Nov Dec<br />

Work Package One: staffing<br />

Student volunteers ‐digitising/processing, fieldsurvey<br />

registering grants/contracts<br />

Research assistant: provision <strong>of</strong> illustrations, distribution<br />

maps (Four Months, PT)<br />

Work Package Two: eco‐fact anaylsis<br />

Specialist reports<br />

C 14 dating<br />

Work Package Three: final chapters<br />

Survey: Céide Fields <strong>and</strong> Belderrig<br />

Survey: Rathalackan <strong>and</strong> area<br />

Survey: Pollatomas <strong>and</strong> area<br />

Behy<br />

Glenulra Enclosure<br />

Céide Fields Visitor Centre<br />

Glenula Scatter<br />

Soils, Geology etc.<br />

History <strong>of</strong> Research<br />

Draft <strong>of</strong> popular text<br />

Work Package Three: dissemination<br />

Ongoing<br />

Work Package Four: reporting for INSTAR<br />

<strong>Report</strong>ing requirements<br />

Figure 1: Indicative work plan for NBNM<strong>2011</strong> as presented in initial proposal<br />

Work Packages One <strong>and</strong> Two<br />

Five main bodies <strong>of</strong> work have been carried out in order to support the final production <strong>of</strong> texts:<br />

charcoal analysis (Dr Lorna O’Donnell), non-wood plant macr<strong>of</strong>ossils analysis (Dr Meriel McClatchie),<br />

GIS work (Emmett O’Keeffe), the provision <strong>of</strong> radiocarbon dates <strong>and</strong>, finally, artefact illustration. Full<br />

reports on the first four <strong>of</strong> these are included here, with illustrations used in the reports as<br />

appropriate.<br />

- Charcoal Analysis, by Lorna O’Donnell<br />

- Plant remains, by Meriel McClatchie<br />

- GIS <strong>and</strong> Spatial Archive, by Emmett O’Keeffe<br />

2

- A summary <strong>of</strong> the radiocarbon dating programme, by Graeme Warren<br />

Work Package Three<br />

Substantial drafts <strong>of</strong> final chapters have been produced for all the areas noted above. Some sections<br />

are final <strong>and</strong> will be made publically available, others will require editing in the context <strong>of</strong> the final<br />

volume as a whole <strong>and</strong> we would not wish these to be public at this stage. We include all <strong>of</strong> these<br />

drafts here. This includes:<br />

- A background to soils <strong>and</strong> geology, by Graeme Warren<br />

- A History <strong>of</strong> Research in <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>, by Seamas Caulfield<br />

- Survey work at Céide Fields <strong>and</strong> Belderrig, by Seamas Caulfield<br />

- Survey work at the Glenamoy – Bartnatra Peninsula, by Noel Dunne<br />

- Survey work at Ballinglen to Palmerstown River, by Gretta Byrne<br />

- Excavations at Behy Court tomb 1963-4 <strong>and</strong> 1969, by Sean Ó Nualláin, Madeline Murray,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Graeme Warren<br />

- Excavations at Glenulra Enclosure 1970-1972, by Seamas Caulfield <strong>and</strong> Graeme Warren<br />

- Excavations associated with the construction <strong>of</strong> the Céide Fields Visitor Centre 1989-1993,<br />

by Gretta Byrne, Noel Dunne <strong>and</strong> Graeme Warren<br />

- Excavations at the Glenulra Scatter, by Gretta Byrne: this now incorporated into the Visitor<br />

Centre report.<br />

Where a chapter is not ready for publication at this stage a paragraph at the start <strong>of</strong> the chapter<br />

summarises the work required for completion. The four excavation reports are not included here;<br />

these have been combined with a further text providing an outline model <strong>of</strong> chronology for the<br />

Céide Hill sub-system. This is ready to be made available to the public as the first synthetic<br />

publication <strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> 40 years <strong>of</strong> archaeological excavations on Céide Hill.<br />

Caulfield <strong>and</strong> Downes continue to work on a draft <strong>of</strong> popular text. Many <strong>of</strong> the sections outlined<br />

above, especially those by Caulfield, will be used in the more popular account <strong>of</strong> A L<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

Fossilised.<br />

3

Part One:<br />

reports on specialist work<br />

4

Creating Digital Archaeological L<strong>and</strong>scapes: An<br />

archaeological GIS for the NBNM project.<br />

Emmett O’Keeffe, UCD School <strong>of</strong> Archaeology<br />

Introduction<br />

This report outlines the construction <strong>of</strong> a GIS for digitally managing <strong>and</strong> analysing the spatial<br />

component <strong>of</strong> the NBNM archive. The report introduces the aims <strong>and</strong> methodology <strong>of</strong> the GIS<br />

component before outlining the main foci <strong>and</strong> outcomes <strong>of</strong> work.<br />

Aims<br />

The general aim <strong>of</strong> the GIS component <strong>of</strong> the NBNM project is to digitise the paper archive <strong>of</strong> four<br />

decades <strong>of</strong> research on the prehistoric l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>. This paper archive includes large<br />

<strong>and</strong> small-scale plans <strong>of</strong> sub-peat <strong>and</strong> extant fieldwall survey, plans <strong>of</strong> excavation cuttings from a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> excavations <strong>of</strong> prehistoric sites <strong>and</strong> detailed mid- <strong>and</strong> post-ex plans from a number <strong>of</strong><br />

excavations. The GIS portion <strong>of</strong> the NBNM project has focused on the digitisation <strong>of</strong> the paper<br />

archive; the georectification <strong>of</strong> all relevant plans; the digitisation <strong>of</strong> the majority <strong>of</strong> these plans; the<br />

integration <strong>of</strong> these with other relevant l<strong>and</strong>scape datasets <strong>and</strong> the production <strong>of</strong> outputs.<br />

The paper archive consists <strong>of</strong> 347 drawings, <strong>of</strong> these, 288 were scanned as part <strong>of</strong> Phase 1 with the<br />

remainder being scanned as part <strong>of</strong> phase 2. These drawings are from a variety <strong>of</strong> sources such as<br />

original primary drawings, excavation reports <strong>and</strong> MA theses (Byrne 1986, Dunne 1985). These<br />

drawings vary in source type <strong>and</strong> consist mainly <strong>of</strong>: pencil drawings on permatrace, inked drawings<br />

on permatrace, pencil drawings on paper, digitally printed or photocopied drawings. The original size<br />

<strong>of</strong> these drawings can vary quite considerably from extremely large sheets <strong>of</strong> permatrace<br />

representing l<strong>and</strong>scape-scale plans <strong>of</strong> sub-peat fieldwalls to A4 sized plans <strong>of</strong> numerous excavation<br />

trenches from a variety <strong>of</strong> archaeological sites.<br />

A methodology was devised to include all relevant drawings within one integrated GIS to allow a series <strong>of</strong><br />

analytical <strong>and</strong> representative options in the future.<br />

The scanning methodology established during phase 1 <strong>of</strong> the GIS project has been continued. All<br />

image scans are monochrome lineart or greyscale, decisions on the most suitable selection were<br />

made on a case by case basis to produce the clearest images possible from the original paper<br />

archive. A st<strong>and</strong>ard scanning resolution <strong>of</strong> 400 dpi was used <strong>and</strong> was increased for 80 images when<br />

deemed necessary. All images were saved as .tiff format. Scanned images are organized into folders<br />

by date <strong>of</strong> scanning <strong>and</strong> all images follow the nomenclature ‘Scan_###_sitename.tif’, for example,<br />

‘Scan_025_Rathlackan.tif’.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the key goals <strong>of</strong> this project has been the georeferencing <strong>of</strong> plans <strong>of</strong> both regional fieldwall<br />

surveys <strong>and</strong> excavations. Georeferencing an image ties that image into a spatial framework so that it<br />

can be accurately plotted within a framework such as the Irish National Grid. A series <strong>of</strong> images,<br />

representing the key foci for this project have been georectified. These vary from regional sub-peat<br />

fieldwall plans to plans <strong>of</strong> individual excavation trenches. This georectification forms the basis for all<br />

digitising work undertaken. Due to the diverse generation methods <strong>of</strong> the paper archive <strong>and</strong> the<br />

variation between different projects <strong>and</strong> different spatial scales a number <strong>of</strong> methods have been<br />

used to georectify images relating to different geographic foci.<br />

5

Figure 1: student volunteers played a very significant role in digitising plans from<br />

excavations<br />

A tiered file structure is used for all data within the project (Figure 2). This tiered file structure for<br />

archaeological data follows the path: NBNM GIS > Archaeological_data > Regional_l<strong>and</strong>scape_name<br />

> <strong>and</strong> is then divided into subfolders containing data relating to spatial information <strong>and</strong> digitised<br />

shapefiles. Each digitised shapefile is contained within a folder relating to the specific scanned image<br />

<strong>and</strong> the spatial location <strong>of</strong> that image, for example the particular excavation trench <strong>of</strong> a particular<br />

archaeological site. The exception to this being the images <strong>and</strong> shapefiles <strong>of</strong> fieldwalls which are<br />

contained within the folder path: Archaeological_data > Regional_survey >. As an example the<br />

digitised shapefile for a mid-excavation plan (scanned as image 022) <strong>of</strong> cutting B at Rathlackan<br />

would be NBNM GIS > Archaeological_data > Rathlackan_Ballinglen_l<strong>and</strong>scape > shapefiles ><br />

cutting_b > mid_ex > scan_022. This file structure is replicated within the organsiation <strong>of</strong> the GIS<br />

layers.<br />

Datasets<br />

Key datasets have been constructed on the basis <strong>of</strong> the paper archive. These datasets are composed<br />

mostly <strong>of</strong> shapefiles outlining features evident on both survey <strong>and</strong> excavation plans. Where features<br />

(fieldwalls, excavation trenches, structural stones, spreads etc.) have been digitised each category <strong>of</strong><br />

feature has normally been given its own shapefile per digitised scan. Where necessary created<br />

shapefiles have been given a variety <strong>of</strong> additional attributes (for instance where stones on an<br />

excavation plan relate to different construction features) to allow more nuanced querying <strong>and</strong><br />

display <strong>of</strong> data. In addition a number <strong>of</strong> databases <strong>of</strong> small scale have been constructed to aid in<br />

displaying key sites <strong>and</strong> features at a variety <strong>of</strong> spatial scales <strong>and</strong> to aid in spatially defining key<br />

georectification anchors.<br />

6

Figure 2: Data Model for NBNM GIS<br />

Results<br />

Regional Survey<br />

All surveyed <strong>and</strong> identified sub-peat prehistoric fieldwalls have been georectified <strong>and</strong> digitised. The<br />

original paper archive contains a wide range <strong>of</strong> paper plans at a variety <strong>of</strong> scales for different parts <strong>of</strong><br />

the sub-peat field systems <strong>of</strong> north <strong>Mayo</strong>. A variety <strong>of</strong> methods have been used in this programme<br />

<strong>of</strong> georectification including the undertaking <strong>of</strong> recent high-grade GPS survey, the relation <strong>of</strong><br />

features (such as the boundaries <strong>of</strong> modern settlement as represented on the paper plans with) with<br />

georectified aerial photographs <strong>and</strong> site visits. The level <strong>of</strong> spatial accuracy <strong>of</strong> the fieldwall<br />

georectification varies across the region <strong>and</strong> in places, such as around the Céide Fields visitor’s<br />

centre it is accurate to within 3 metres. However, the level <strong>of</strong> accuracy may drop in places (such as<br />

around Ballyknock Hill) to approximately 10-15 metres due to the georectification method for<br />

fieldwalls in these areas.<br />

A series <strong>of</strong> structures identified as part <strong>of</strong> Gretta Byrnes survey <strong>of</strong> eastern north <strong>Mayo</strong> have been<br />

georectified <strong>and</strong> digitised using co-ordinates derived from 1:2,500 OS maps. These structures have<br />

then been overlaid on regional fieldwall maps <strong>and</strong> their accuracy demonstrated. However, due to<br />

variation in the spatial accuracy <strong>of</strong> the north <strong>Mayo</strong> fieldwalls a statement <strong>of</strong> error in the region <strong>of</strong> 5-<br />

10 metres is estimated for these structures.<br />

7

Figure 3: survey work at Céide Fields, identifying key wall junctions to be probed <strong>and</strong> reidentified<br />

in advance <strong>of</strong> GPS survey.<br />

Behy Court Tomb<br />

Plans <strong>of</strong> Behy court tomb which outline: the overall post-excavation extent <strong>of</strong> the tomb; <strong>and</strong> some<br />

architectural detail <strong>of</strong> the chambers, the location <strong>of</strong> identified archaeological features <strong>and</strong> positions<br />

<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ile lines have been georectified on the basis <strong>of</strong> co-ordinates derived from recent high-grade<br />

GPS survey. Given the method <strong>of</strong> georectification <strong>of</strong> these plans their spatial accuracy is <strong>of</strong> a high<br />

degree (

Figure 4: example <strong>of</strong> outputs at Céide Fields Visitor Centre: all excavation trenches from<br />

39 years <strong>of</strong> excavation: red –Behy (1963-1964, 1969); yellow - Glenulra Enclosure<br />

(1970-1972); blue excavations in advance <strong>of</strong> the visitor centre (1989-1992)<br />

Excavation plans were available in the archive for fifteen individual trenches, some demonstrating<br />

different phases <strong>of</strong> excavation, <strong>and</strong> all <strong>of</strong> these have been digitised.<br />

Belderg Beg<br />

Trench locations for a series <strong>of</strong> excavation seasons at Belderg Beg have been georectified using a<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> composite base plans, aerial photographs, high-grade GPS survey <strong>and</strong> site visits. The<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> excavation trench locations have been positively identified during fieldwork <strong>and</strong><br />

accurately mapped (

Figure 5: Belderg Beg, Area F: example <strong>of</strong> GIS<br />

Glenulra Enclosure<br />

A composite base plan from a series <strong>of</strong> survey episodes (most recently by the UCD School <strong>of</strong><br />

Archaeology MA class) representing the major archaeological features <strong>of</strong> Glenulra enclosure has<br />

been georectified <strong>and</strong> digitised. This georectification was undertaken using a composite <strong>of</strong> paper<br />

base plans <strong>and</strong> recent high-grade GPS survey. Cross-checking with aerial photographs <strong>and</strong> multiple<br />

episodes <strong>of</strong> GPS survey demonstrates a high-level <strong>of</strong> spatial accuracy (

Rathlackan<br />

As a result <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> GPS survey points for the excavations at Rathlackan the base-plan for the site<br />

has been georeferenced using values derived from the OSI online mapping service <strong>and</strong> translated<br />

from ITM to NGR values. Following subsequent cross-checking against 1 metre resolution aerial<br />

photographs an error <strong>of</strong> 5-10 metres must be taken into account for the Rathlackan excavation base<br />

plan. A total <strong>of</strong> forty-four excavation plans from twelve separate cuttings have been georectified <strong>and</strong><br />

the vast majority <strong>of</strong> these have been digitised. As the base plan was used to georectify each <strong>of</strong> the<br />

plans for the individual excavation cuttings the error <strong>of</strong> 5-10 metres is systematic <strong>and</strong> all plans are<br />

internally consistent. The error could be corrected easily in the future by using high-grade survey.<br />

Additional Datasets<br />

A series <strong>of</strong> additional datasets derived from a number <strong>of</strong> contexts (SMR, EPA, GSI etc.) have been<br />

incorporated into the GIS. This data has been simplified <strong>and</strong> displayed at a variety <strong>of</strong> scales to allow<br />

outputs <strong>of</strong> value to the NBNM project. Figure X shows the relationship <strong>of</strong> fieldwalls, megalithic<br />

monuments as recorded in the SMR <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> use. This clearly demonstrates that fieldwalls do not<br />

survive in areas <strong>of</strong> modern cultivation (green) although monuments do. The presence <strong>of</strong> both<br />

fieldwalls <strong>and</strong> monuments in areas <strong>of</strong> bog (brown) suggests that walls <strong>and</strong> megaliths should be<br />

found together <strong>and</strong> this implies that fieldwalls once covered the l<strong>and</strong> suitable for cultivation as well.<br />

In passing it should be noted that the SMR locations are not accurate for many monuments <strong>and</strong> that,<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> the errors noted above for the fieldwalls, they are more accurately located than most<br />

<strong>of</strong> the SMR sites.<br />

Figure 7: L<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> the survival <strong>of</strong> different aspects <strong>of</strong> the Neoltihic <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

L<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong><br />

11

L<strong>and</strong>scape Modelling<br />

Aerial photographs (1 metre resolution) <strong>and</strong> map-derived elevation data (50 metre resolution)<br />

provided by <strong>Mayo</strong> County Council have been used as background display <strong>and</strong> analysis data within<br />

the GIS. These datasets have also been used to created draped 3D digital l<strong>and</strong>scape models <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong><br />

<strong>Mayo</strong> to which various aspects <strong>of</strong> the archaeological record have been added (such as the sub-peat<br />

field systems). The elevation data has also been used to generate a series <strong>of</strong> coarse resolution<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape models <strong>of</strong> viewsheds, aspects, slopes etc.<br />

Figure 8: 3D view <strong>of</strong> Ballyknock ( on left) <strong>and</strong> main Céide Fields Complex,<br />

looking South South West. 2x vertical exaggeration.<br />

Outputs<br />

A series <strong>of</strong> 2D plans moving in scale from the entire extent <strong>of</strong> the north <strong>Mayo</strong> sub-peat field systems<br />

to individual excavation trenches have been produced. A series <strong>of</strong> short movies examining aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

the north <strong>Mayo</strong> sub-peat fieldwalls have been produced from the 3D l<strong>and</strong>scape models.<br />

The key output <strong>of</strong> this part <strong>of</strong> the NBNM project is the GIS itself which forms the basis for future data<br />

management <strong>and</strong> output production. The GIS including all digitised data <strong>and</strong> outputs is currently 54<br />

gigabytes <strong>and</strong> represents a significant archive for past research on the prehistoric archaeology <strong>of</strong><br />

north <strong>Mayo</strong> <strong>and</strong> a basis for future endeavours.<br />

12

Radiocarbon Dating<br />

A further tranche <strong>of</strong> radiocarbon dates were obtained in <strong>2011</strong>. These are reported below, alongside<br />

all archaeological C14 dates for the sites. Full discussion will take place in the appropriate final<br />

reports.<br />

13

Céide Visitor Centre<br />

Cal Date (2 sigma)<br />

Error<br />

C14<br />

Context<br />

Species<br />

Sample No<br />

Feature No<br />

Cutting<br />

Lab Number<br />

GrN-20032 19 - Plough mark 2390 40 750 - 380 cal BC<br />

UB-18598 25 F.56 39 Betula sp. Charcoal layer site <strong>of</strong> Building 3672 30 2139 - 1957 cal BC<br />

UCD-0268 25 F.56 37 bulk charcoal Charcoal layer site <strong>of</strong> Building 3660 50 2200 - 1890 cal BC<br />

UCD-0271 25 F.56 38 bulk charcoal Charcoal layer site <strong>of</strong> Building 3800 50 2460 - 2040 cal BC<br />

UCD-0272 10 B 35B bulk charcoal Hearth 3835 50 2470 - 2140 cal BC<br />

UCD-0267 10 B 35A bulk charcoal Hearth 3840 50 2470 - 2140 cal BC<br />

UB-18597 10B 35 Corylus avellana hearth (? Charcoal spread?) 3815 31 2434 - 2131 cal<br />

UBA-16460 C F.3 3 Betula -charcoal Charcoal spread 3774 34 2296 - 2126 cal BC<br />

UB-18596 H F.11 18 Betula sp. burnt organic layer 3722 31 2203- 2030 cal BC<br />

UCD-0269 H F.9 21 bulk charcoal Charcoal spread 3600 50 2140 - 1770 cal BC<br />

UCD-0270 H F.9 11 bulk charcoal Charcoal spread 3650 50 2200 - 1890 cal BC<br />

UBA-16675 H F.9 16 Betula -charcoal Charcoal spread 3852 27 2459 - 2207 cal BC<br />

UB-18595 H F.13 13 Ilex aquifolium fill <strong>of</strong> shallow trench 3791 28 2332-2137 cal BC<br />

UBA-16461 H F.15 S.19 Maloideae -charcoal fill <strong>of</strong> ash pit, sealed by F9 4111 48 2873 - 2501 cal BC<br />

14

RATHLACKAN<br />

Lab Number<br />

F no<br />

S. No<br />

Context<br />

Beta-48102 F.6 Hearth <strong>of</strong> house 4110 60 2880-2490 cal BC<br />

Beta-63836 F.6 Hearth <strong>of</strong> house 4040 60 2870-2450 cal BC<br />

Material Dated<br />

C14<br />

Error<br />

Cal Range<br />

(95.4%)<br />

Beta-76590 F.103 Slit in top <strong>of</strong> socket in SW end<br />

Chamber 3<br />

4130 80 2900-2490 cal BC<br />

Beta-76586 F.30 With secondary pottery in<br />

Chamber 3<br />

3630 80 2210-1750 cal BC<br />

Beta-76584 F.31 With secondary pottery in<br />

Chamber 3<br />

3640 80 2300-1750 cal BC<br />

Beta-76585 F.44 Deposit in N end <strong>of</strong> CH 3<br />

above basal stones<br />

4090 70 2880-2480 cal BC<br />

Beta-76588 F.58 Spread in Ch3 4640 80 3650-3100 cal BC<br />

UBA-16467 F.95 S.69 Layer in Ch.3 corylus ‐charcoal 4674 25 3617 - 3370 cal BC<br />

UBA-16466 F.87 S.67 Layer in Ch.3 corylus ‐charcoal 4685 26 3625 - 3371 cal BC<br />

Corylus<br />

UBA-18600 F.65 S.71 layer in Ch. 2<br />

avellana<br />

4655 43 3625 - 3356 cal BC<br />

UBA-16463<br />

Fill <strong>of</strong> pit in Chamber 3 corylus –<br />

F.66 S.50<br />

charcoal<br />

3655 28 2134 - 1945 cal BC<br />

Beta-76589 F.66 Fill <strong>of</strong> pit in Chamber 3 4390 240 3700-2300 cal BC<br />

UBA-18599 F.66 S.64 Fill <strong>of</strong> pit in Chamber 3 Salix sp. 4121 31 2867 - 2579 cal BC<br />

UBA-16462 F.21 S.14 Spread on court surface corylus – shell 4559 25 3483-3110 cal BC<br />

Beta-76583 F.21 Spread on court surface 4110 90 2890-2470 cal BC<br />

Beta-76587 F.21 Spread on court surface 4520 80 3500-2900 cal BC<br />

UBA-16465 F.78 S.73 Stakehole in court corylus ‐shell 4641 25 3514 - 3361 cal BC<br />

15

Cal Range<br />

(95.4%)<br />

Error<br />

C14<br />

Material<br />

Dated<br />

Context<br />

S. No<br />

F no<br />

Lab Number<br />

Beta-76591 F.68 Deposit surrounding hearth in<br />

court<br />

UBA-16464<br />

black layer surrounding<br />

F.68 S.61 hearth stone in court<br />

UBA-16677<br />

Thin layer <strong>of</strong> material under<br />

F. 107 S.75 hearth in court<br />

corylus ‐shell<br />

corylus –<br />

charcoal<br />

4570 90 3650-3000 cal BC<br />

4600 27 3498 - 3141 cal BC<br />

4449 26 3333 - 3014 cal BC<br />

16

GLENULRA ENCLOSURE<br />

Notes<br />

Cal BC (95.4% prob.)<br />

Error<br />

BP uncal<br />

Description<br />

Material<br />

Sample<br />

Cutting<br />

Lab Code<br />

SI-1464<br />

bulk<br />

charcoal 4460 115 3510 - 2880 cal BC<br />

possibly<br />

C.127<br />

UBA-16676<br />

F4<br />

betula -<br />

charcoal charcoal spread/hearth 4616 24 3498 - 3352 cal BC<br />

possibly<br />

C.127<br />

17

BELDERG BEG<br />

Cal BC<br />

(95.4%<br />

prob.)<br />

Error<br />

BP uncal<br />

Description<br />

Material<br />

Sample<br />

Cutting<br />

Lab Code<br />

AREA A<br />

UBA-18594 A1 alnus charcoal from exterior EN vessel 3604 32 2110 - 1885 cal<br />

BC<br />

UBA-18591 A1 s.002 Betula charcoal adhering to quern stone 3753 28 2281 - 2040 cal<br />

BC<br />

SI – 1475 A2 bulk charcoal Charcoal associated with a flint scatter at in Area A2 2905 75 1370 - 900 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16672 A2 S.096 horn (bovid) horn artefact 3482 42 1908 - 1691 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16673 A2 S.097 horn (bovid) horn 2567 24 804 - 594 cal BC<br />

QL-1689 A1 tree root, site A1 1630 30 340 - 540 cal AD<br />

QL-1690 A1 charcoal site A1 3800 30 2350 - 2130 cal BC<br />

AREA B: house<br />

SI – 1474 B1 bulk charcoal Charcoal within the roundhouse associated with artefacts 2295 75 750 - 100 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16670 B1 S.242 corylus – charcoal Charcoal sample from wall trench <strong>of</strong> Phase 1 round house: possible structural<br />

wattle (C.109)<br />

3077 25 1415 - 1271 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16669 B1 S.201 Salix ‐charcoal Charcoal sample from wall trench <strong>of</strong> Phase 1 round house: possible structural<br />

wattle (C.109)<br />

3117 23 1441 - 1316 cal BC<br />

SI – 1473 B1 Burnt block <strong>of</strong> wood from post hole <strong>of</strong> porch <strong>of</strong> phase 2/3 roundhouse. 3170 85 1640 - 1210 cal BC<br />

18

Lab Code<br />

Cutting<br />

Sample<br />

Material<br />

AREA B: cultivation <strong>and</strong><br />

charcoal<br />

GU-11268 B (?) basal peat Sample BB1: basal peat 2450 35 760 - 400 cal BC<br />

GU-11269 B (?) basal peat Sample BB2: basal peat 2730 40 980 - 800 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16671 B2A S.253 corylus – charcoal Charcoal sample, predates ard cultivation 3707 45 2272 - 1959 cal BC<br />

Description<br />

BP uncal<br />

Error<br />

Cal BC<br />

(95.4%<br />

prob.)<br />

UBA-18593<br />

UBA-18592<br />

B2P<br />

West<br />

B2T<br />

East<br />

AREA C: fence posts<br />

UBA‐16674 C1 S.294 quercus ‐wooden<br />

fence post<br />

s.322 betula 3536 29 1948 - 1769 cal<br />

BC<br />

s.235 salix sp. 3621 27 2114 - 1898 cal<br />

BC<br />

From pointed oak stake/post along line <strong>of</strong> the wall built on the peat 3546 46 2018 - 1750 cal BC<br />

SI- 1472 C1 quercus ‐wooden<br />

fence post<br />

SI - 1471 C1 quercus ‐wooden<br />

fence post<br />

QL-1688 C1 quercus ‐wooden<br />

fence post<br />

From pointed oak stake/post along line <strong>of</strong> the wall built on the peat 3210 85 1690 - 1290 cal BC<br />

From pointed oak stake/post along line <strong>of</strong> the wall built on the peat 3220 85 1700 - 1300 cal BC<br />

From pointed oak stake/post along line <strong>of</strong> the wall built on the peat 3300 30 1670-1500 cal BC<br />

19

TREES<br />

Cal BC (95.4% prob.)<br />

Error<br />

BP uncal<br />

Description<br />

Material<br />

Cutting<br />

Lab Code<br />

UBA‐16468 Belderg Beg pinus ‐wood tree 4437 25 3327 - 2934 cal BC<br />

SI-1470 Belderg Beg pinus ‐wood tree 4220 95 3080 - 2490 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16469 Geevraun pinus ‐wood tree 4026 24 2618 - 2474 cal BC<br />

UCD-C47 Geevraun pinus ‐wood tree 4210 60 2920 - 2610 cal BC<br />

UBA‐16470 Belderg More pinus ‐wood tree 4531 30 3361 - 3103 cal BC<br />

UCD-C49 Belderg More pinus ‐wood tree 4580 60 3520 - 3090 cal BC<br />

20

Charcoal analysis from <strong>Neolithic</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> <strong>Mayo</strong>,<br />

Lorna O’Donnell<br />

Introduction<br />

Charcoal is the product <strong>of</strong> chemical reactions that occur when wood is heated (i.e. thermal<br />

decomposition) (Smart <strong>and</strong> H<strong>of</strong>fman 1988, 172). It is frequently found on Irish archaeological<br />

sites, in general in greater quantities than plant remains. Its uses in environmental<br />

archaeology range from being a suitable material for radiocarbon dating, to an<br />

environmental indicator.<br />

This report describes the analysis <strong>of</strong> wood <strong>and</strong> charcoal samples from five sites in the Céide<br />

fields complex Co. <strong>Mayo</strong>, excavated by Pr<strong>of</strong>. Seamas Caulfield, Ms Gretta Byrne <strong>and</strong> Mr. Noel<br />

Dunne.<br />

During the excavations, bulk samples were taken for future environmental work. Current<br />

funding under the INSTAR grant scheme by the Heritage Council has allowed for processing<br />

<strong>and</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> these samples. Previously, some charcoal analysis was undertaken by Mr.<br />

Donal Synott from the National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin. In 2010, the author was asked<br />

to assess samples from five <strong>of</strong> the sites; Glenulra enclosure (E24) (Caulfield et al 2009a),<br />

Glenulra Scatter (92E140) (Byrne et al 2009a), Céide Visitor Centre (E494) (Byrne et al<br />

2009b), Belderg Beg (E109) (Caulfield et al 2009b) <strong>and</strong> Rathlackan (E580) (Byrne et al 2009c)<br />

(O’Donnell 2010). Following this assessment <strong>and</strong> further sample processing, 82 samples<br />

were selected for full analysis from the five sites.<br />

The aims <strong>of</strong> the work are as follows:<br />

• Assess suitable short lived material for radiocarbon dating<br />

• Examine any wood selection strategies on the sites<br />

• Compare woodl<strong>and</strong> flora over time, incorporating other environmental data<br />

Sampling strategy<br />

The sampling strategy on site consisted mainly <strong>of</strong> targeted sampling <strong>of</strong> charcoal rich<br />

deposits.<br />

Methodology<br />

Processing<br />

Soil samples were processed in 2009-2010 by means <strong>of</strong> flotation. Mechanical flotation tanks<br />

were used. This involved the agitation <strong>of</strong> the soil sample in a water filled tank lined with a<br />

1mm nylon mesh. This releases the lighter environmental material (flot) such as seeds <strong>and</strong><br />

charcoal from the soil matrix. This lighter fraction is collected in a sieve <strong>of</strong> 300μm mesh size.<br />

Once dry, the retent was sorted using a stack <strong>of</strong> sieves with a mesh size <strong>of</strong> 4mm, 2mm <strong>and</strong><br />

1mm. Charcoal larger than 2mm in size was sorted out <strong>of</strong> the retent <strong>and</strong> the flot, all seeds<br />

21

are extracted <strong>and</strong> any finds (bone, pottery, flint <strong>and</strong> other such archaeological material) are<br />

also sorted from the retent. All material retrieved from residue-sorting was recorded.<br />

Charcoal identification<br />

Each piece <strong>of</strong> charcoal was examined <strong>and</strong> orientated first under low magnification (10x-40x).<br />

They were then broken to reveal their transverse, tangential <strong>and</strong> longitudinal surfaces.<br />

Pieces were mounted in plasticine, <strong>and</strong> examined under a metallurgical microscope with<br />

dark ground light <strong>and</strong> magnifications generally <strong>of</strong> 20x <strong>and</strong> 40x.<br />

Wood identification<br />

Each wood piece was identified by a first selection under a binocular microscope at a<br />

magnification <strong>of</strong> 10x-40x. This was used to discern features such as ring growth or insect<br />

channels. Samples one cell thick was taken with a razor blade from the transverse, radial <strong>and</strong><br />

tangential planes <strong>of</strong> the wood. Analysis <strong>of</strong> thin sections was completed under a transmitted<br />

light microscope, at magnifications <strong>of</strong> 10x, 20x <strong>and</strong> 40x.<br />

Each taxon or species will have anatomical characteristics that are particular to them, <strong>and</strong><br />

these are identified by comparing their relevant characteristics to keys (Schweingruber 1978;<br />

Hather 2000 <strong>and</strong> Wheeler et al 1989) <strong>and</strong> a reference collection supplied by the National<br />

Botanical Gardens <strong>of</strong> Irel<strong>and</strong>, Glasnevin.<br />

Details <strong>of</strong> charcoal recording<br />

The general age group <strong>of</strong> each taxa per sample was recorded, <strong>and</strong> the growth rates were<br />

classified as slow, medium, fast or mixed. Any ring widths were measured using electronic<br />

calipers. The ring curvature <strong>of</strong> the pieces was also noted – for example weakly curved annual<br />

rings suggest the use <strong>of</strong> trunks or larger branches, while strongly curved annual rings<br />

indicate the burning <strong>of</strong> smaller branches or trees (Figure. 1). Tyloses in vessels in species<br />

such as oak can denote the presence <strong>of</strong> heartwood. These occur when adjacent parenchyma<br />

cells penetrate the vessel walls (via the pitting) effectively blocking the vessels (Gale 2003,<br />

37). Insect infestation is usually denoted by round holes, <strong>and</strong> is considered to be caused by<br />

burrowing insects. Their presence normally suggests the use <strong>of</strong> decayed degraded wood,<br />

which may have been gathered from the woodl<strong>and</strong> floor or may have been stockpiled. Short<br />

lived twigs with strongly curved annual rings were selected for radiocarbon dating.<br />

Figure. 1 Ring curvature. Weakly curved rings indicate the use <strong>of</strong> trunks or large<br />

branches. (Marguerie <strong>and</strong> Hunot 2007, p.1421).<br />

22

Results<br />

Overall charcoal<br />

83 samples from five sites were fully analysed. 4196 charcoal fragments were identified,<br />

including thirteen wood taxa. The main trees present are birch (Betula sp.), oak (Quercus<br />

sp.), hazel (Corylus avellana) <strong>and</strong> alder (Alnus sp.). Other wood taxa include ash (Fraxinus<br />

sp.), ivy (Hedera helix), holly (Ilex aquifolium), pomaceous fruitwood (Maloideae), pine (Pinus<br />

sp.), willow (Salix sp.) yew (Taxus baccata), elm (Ulmus sp.) <strong>and</strong> alder/hazel (Alnus/Corylus)<br />

(Figure 2, Table 1). Oak <strong>and</strong> willow were also identified from waterlogged wood samples<br />

from Belderg Beg.<br />

Pinus<br />

0.1%<br />

Maloideae<br />

1.6%<br />

Ilex<br />

2.7%<br />

Quercus<br />

23.7%<br />

Hedera<br />

0.1%<br />

Corylus/Alnus<br />

0.0%<br />

Salix<br />

Taxus<br />

0.0%<br />

Ulmus<br />

0.1%<br />

7.4% Alnus<br />

Alnus<br />

15.5%<br />

Betula<br />

Corylus<br />

22.7%<br />

Fraxinus<br />

0.3%<br />

Betula<br />

25.8%<br />

Corylus<br />

Corylus/Alnus<br />

Fraxinus<br />

Hedera<br />

Ilex<br />

Maloideae<br />

Pinus<br />

Quercus<br />

Salix<br />

Taxus<br />

Ulmus<br />

Figure 2 Total charcoal results from the five sites: N=4196 fragments<br />

Alnus 650<br />

Betula 1082<br />

Corylus 954<br />

Corylus/Alnus 1<br />

Fraxinus 13<br />

Hedera 3<br />

Ilex 114<br />

23

Maloideae 66<br />

Pinus 3<br />

Quercus 994<br />

Salix 309<br />

Taxus 1<br />

Ulmus 6<br />

Table 1 Total charcoal fragments from the five sites<br />

Glenulra enclosure E24 Middle <strong>Neolithic</strong><br />

Charcoal was examined from S004, the fill <strong>of</strong> a hearth (contextual information taken from<br />

the sample bag). Birch, oak, pine <strong>and</strong> yew were identified from this sample (Figure 3). Ring<br />

counts range between two <strong>and</strong> four. Annual rings on the birch are strongly curved, indicating<br />

branches. In contrast, both the oak <strong>and</strong> pine annual rings are weakly curved, suggesting they<br />

were derived from larger branches or trunks. The presence <strong>of</strong> tyloses coupled with the<br />

weakly curved annual rings in the oak suggests that heartwood was burnt. Growth rates are<br />

medium (Table 2).<br />

3%<br />

55%<br />

39%<br />

Betula<br />

Pinus<br />

Quercus<br />

Taxus<br />

3%<br />

Figure 3 Total charcoal from E24 : N= 33 fragments<br />

24

Glenulra Scatter 92E140 Middle <strong>Neolithic</strong><br />

Charcoal was recorded from two contexts from this site, a charcoal rich spread (F6) (S005)<br />

<strong>and</strong> a stakehole (F8) (S009) (Table 3). Five wood taxa were identified, the main tree present<br />

is hazel.<br />

Mainly hazel along with low levels <strong>of</strong> willow, pomaceous fruitwood, oak, <strong>and</strong> birch were<br />

identified from the charcoal spread (F6). The level <strong>of</strong> charcoal within the posthole fill (F8) is<br />

low. Two pieces <strong>of</strong> hazel <strong>and</strong> one fragment <strong>of</strong> pomaceous fruitwood were recorded from<br />

here. The low level <strong>of</strong> charcoal within the posthole indicates that it was not burnt in situ but<br />

more likely the post decayed or was removed. Charcoal present could be the results <strong>of</strong> on<br />

site domestic burning.<br />

Annual ring counts range between two <strong>and</strong> ten from Glenulra. All <strong>of</strong> the pieces are <strong>of</strong><br />

medium growth <strong>and</strong> have strongly curved annual rings, indicating that branches or twigs<br />

were burnt.<br />

5%<br />

2%<br />

5%<br />

2%<br />

Betula<br />

Corylus<br />

Maloideae<br />

Quercus<br />

Salix<br />

86%<br />

Figure 4 Charcoal identifications from 92E140: N=41fragments<br />

25

Céide Visitor Centre (E494) Late <strong>Neolithic</strong>/Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

Charcoal was examined from nine contexts from this site (Table 4). Seven wood taxa in total<br />

were identified including oak, birch, hazel/alder, pomaceous fruitwood, willow, hazel <strong>and</strong><br />

holly. The main tree present is birch (Figure 5).<br />

3%<br />

3%<br />

9%<br />

2%<br />

0%<br />

16%<br />

67%<br />

Betula<br />

Corylus<br />

Corylus/Alnus<br />

Ilex<br />

Maloideae<br />

Quercus<br />

Salix<br />

Figure 5 Total charcoal identifications from E494 : N=462 fragments<br />

Birch, hazel <strong>and</strong> willow were recorded from Cutting C F3 (S003). In comparison, mainly birch<br />

with holly, pomaceous fruitwood, oak <strong>and</strong> willow were identified from Cutting H, F9 (S016) a<br />

comparable charcoal layer.<br />

From Cutting 10B (S035), a hearth, mainly hazel along with willow <strong>and</strong> oak were identified.<br />

Previous work by Donal Synott <strong>of</strong> the Botanical Gardens in Glasnevin has also identified<br />

these taxa, along with holly <strong>and</strong> alder.<br />

Primarily birch, hazel <strong>and</strong> holly were recorded from Cutting H ‘Trench’ F13 (S013), while<br />

birch, pomaceous fruitwood <strong>and</strong> willow were noted from Cutting H ‘Trench’ F14 (S022).<br />

Two fills were examined from Cutting H, F19, an ash pit. F15 (S019) is the upper fill <strong>and</strong> it<br />

contains birch, hazel, pomaceous fruitwood, hazel/alder, oak <strong>and</strong> willow. Below this, F16<br />

(S029) an ashy layer was excavated, no charcoal was recorded in this sample. Birch, holly,<br />

pomaceous fruitwood, oak <strong>and</strong> willow were identified from Cutting H ‘Trench’ F20 (S026).<br />

26

Oak <strong>and</strong> birch were recorded from Cutting H, F24C (S028), the fill <strong>of</strong> a stakehole. The low<br />

level <strong>of</strong> charcoal indicates that the post was not burnt in situ.<br />

From Cutting 25, F56 (S039), a charcoal layer, birch, hazel, pomaceous fruitwood, oak <strong>and</strong><br />

willow were identified.<br />

Annual ring counts range from 1 to 26 from the Céide visitor centre site. All <strong>of</strong> the fragments<br />

have strongly curved annual rings suggesting the burning <strong>of</strong> branches or twigs with the<br />

exception <strong>of</strong> oak from F9, F24C <strong>and</strong> F10B which has weakly curved rings. Growth is medium<br />

in most cases, with the exception <strong>of</strong> birch from 24C which has a faster rate <strong>of</strong> growth. In the<br />

author’s experience, willow <strong>and</strong> birch <strong>of</strong>ten have faster rates <strong>of</strong> annual growth than other<br />

frequently identified Irish taxa such as hazel <strong>and</strong> alder.<br />

fragment count<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

CTG C<br />

F3<br />

CTG<br />

10B<br />

CTG H<br />

F9<br />

CTG H<br />

F13<br />

CTG H<br />

F14<br />

CTG H<br />

F15<br />

CTG H<br />

F20<br />

CTG H<br />

F24C<br />

CTG H<br />

F56<br />

Salix<br />

Quercus<br />

Maloideae<br />

Ilex<br />

Corylus/Alnus<br />

Corylus<br />

Betula<br />

Charcoal<br />

rich soil<br />

Trench Charcoal<br />

rich soil<br />

Trench Trench Ash pit Trench Posthole Charcoal<br />

layer<br />

Figure 6 Charcoal from different contexts E494: N=462<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the samples are derived from Cutting H, with the exception <strong>of</strong> F3 (Cutting C) F56<br />

(Cutting 25) <strong>and</strong> Cutting 10B. The results are very homogenous, birch dominates all the<br />

contexts with the exception <strong>of</strong> Cutting 10B which contains mainly hazel (Figure 6). Hazel is<br />

also important in F24C, although this must be interpreted with caution, as only six fragments<br />

in total were identified from the context. When the results are phased through time period,<br />

it is clear that hazel <strong>and</strong> willow both play a larger role in the Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> identifications<br />

than during the Later <strong>Neolithic</strong> (Figure 7). F24C is dated tentatively to the Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

through association, the high levels <strong>of</strong> birch are comparable to both the Later <strong>Neolithic</strong><br />

samples (F15) <strong>and</strong> the Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> ones (F3, 9, 13, 14 <strong>and</strong> 20).<br />

27

fragment count<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

L Neo<br />

EBA<br />

Salix<br />

Quercus<br />

Maloideae<br />

Ilex<br />

Corylus/Alnus<br />

Corylus<br />

Betula<br />

Figure 7 Phased identifications from E494 : N= 367 (L Neo = 47, EBA = 320).<br />

Belderg Beg E109 Early/Middle <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong><br />

Charcoal was analysed from 48 samples from Belderg Beg (Table 5). A further thirteen<br />

samples were assessed but not selected for analysis (Table 6). Ten wood taxa were identified<br />

from the site; the results are dominated by oak, birch, alder <strong>and</strong> hazel (Figure 8).<br />

0.0%<br />

5.6%<br />

26.6%<br />

1.2%<br />

2.5%<br />

17.3%<br />

0.1%<br />

0.4%<br />

21.9%<br />

24.4%<br />

Alnus<br />

Betula<br />

Corylus<br />

Fraxinus<br />

Hedera<br />

Ilex<br />

Maloideae<br />

Pinus<br />

Quercus<br />

Salix<br />

Figure 8 Total charcoal identifications E109 : N= 2933<br />

28

35<br />

30<br />

no <strong>of</strong> samples<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Alnus<br />

Betula<br />

Corylus<br />

Fraxinus<br />

Hedera<br />

Ilex<br />

Maloideae<br />

Pinus<br />

Quercus<br />

Salix<br />

Figure 9 No <strong>of</strong> samples each taxa occurred in<br />

Birch was identified in 30 samples along with alder. Oak was noted in 29, while hazel was<br />

recorded in 27 samples. These four main taxa were clearly frequently used across the site.<br />

Willow was noted in 19, while holly was identified in 17. The rest <strong>of</strong> the taxa were identified<br />

in 8 or less samples (Figure 9).<br />

From Glenulra enclosure (E24), Glenulra Scatter (92E140), Céide Visitor Centre (E494) <strong>and</strong><br />

Rathlackan (E580) a sub-sample <strong>of</strong> 100 fragments was identified from each sample, following<br />

recommendations from British sites (Keepax 1988, 200). Recent research from the author<br />

has indicated that in prehistoric Irish sites, given our more limited floristic diversity than<br />

Britain, it is suitable to analyse 80 fragments per sample (O’Donnell <strong>2011</strong>, 56). Saturation<br />

curves <strong>of</strong> when new taxa occurred were examined from Belderg Beg. From S319, the last<br />

new species identified was holly at fragment 27 (Figure 10a). In comparison, the last new<br />

species recorded from S324 was hazel <strong>and</strong> fragment 40 (Figure 10b). From S332, holly was<br />

the last new species recorded at fragment 14 (Figure 10c). Based on these cumulative<br />

frequency curves <strong>and</strong> previous research, it was aimed to identify 80 fragments from each<br />

sample from Belderg Beg. The reason that this methodology was not applied to the other<br />

sites is because they have a low number <strong>of</strong> samples <strong>and</strong> in the case <strong>of</strong> Rathlackan a low level<br />

<strong>of</strong> charcoal generally. Therefore if present a sub-sample <strong>of</strong> 100 fragments was analysed from<br />

these samples or if this number <strong>of</strong> fragments was not present, all identifiable pieces were<br />

identified.<br />

29

new taxa occurrence<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100 120<br />

fragment count<br />

Figure 10a Saturation curve S319<br />

5<br />

new taxa occurrence<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100 120<br />

fragment count<br />

Figure 10b Saturation curve S324<br />

5<br />

new taxa occurrence<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

0 20 40 60 80 100 120<br />

fragment count<br />

Figure 10c Saturation curve S332<br />

30

Area A<br />

A long length <strong>of</strong> <strong>Neolithic</strong> field wall <strong>and</strong> some associated features were identified from here,<br />

which was located in the very centre <strong>of</strong> the site. The charcoal spreads, cattle horn, <strong>and</strong> a<br />

range <strong>of</strong> other deposits seem to primarily date to the Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong> but include Iron <strong>Age</strong><br />

dates.<br />

A small alder branch was located adhering to pot (find no). Some birch charcoal was<br />

identified adhering to a quern (S. 002). A mixture <strong>of</strong> mainly oak, with hazel, birch <strong>and</strong> ivy was<br />

noted from a shallow area near a pit (S. 019). Underlying a brown habitation layer, oak only<br />

was identified from S. 022, which may indicate some structural remains. Mainly oak, hazel<br />

<strong>and</strong> birch, along with pine <strong>and</strong> alder were identified from a charcoal spread (S. 035).<br />

A charcoal spread in trench 1 contained birch, hazel, ivy <strong>and</strong> oak (S.027). A further charcoal<br />

spread from this area contained mainly alder <strong>and</strong> birch (S.040).<br />

A hazel branch was analysed which was found in association with a horn (S096). 25<br />

fragments were identified, the ring width pattern indicate that these are all from the one<br />

branch. Nine annual rings were counted on this roundwood. A high level <strong>of</strong> insect holes was<br />

present indicating that the branch was quite degraded <strong>and</strong> insect ridden before it was burnt<br />

(Plate 1).This may represent a hazel h<strong>and</strong>le element which was fixed to the horn.<br />

Plate 1 Insect holes from charcoal S096<br />

31

Area B<br />

Area B is located at the north east corner <strong>of</strong> the site <strong>and</strong> included the remains <strong>of</strong> a<br />

substantial roundhouse (Caulfield et al 2009b, 10). The house may have three phases,<br />

although clearly identifying which structural features date to which phase is problematic.<br />

A variety <strong>of</strong> wood taxa including birch, hazel, ash, holly, pomaceous fruitwood, oak <strong>and</strong><br />

willow were identified from S. 200, taken from a pit under flat stones. Alder, birch, hazel <strong>and</strong><br />

willow were all noted from S. 205, which was sampled under small stones around the sill<br />

stone. Alder, hazel, oak <strong>and</strong> willow were identified from a sample amongst stones (S234). A<br />

charcoal spread in trench B2A contained alder, birch, hazel, oak <strong>and</strong> willow (S.253).<br />

100%<br />

fragment count<br />

80%<br />

60%<br />

40%<br />

20%<br />

Salix<br />

Quercus<br />

Maloideae<br />

Ilex<br />

Corylus<br />

Betula<br />

Alnus<br />

0%<br />

201 213 226 238 241 242 255 254<br />

Figure 11 Charcoal samples from constructional elements at E109 : N=457<br />

Charcoal was identified from seven samples taken from the wall trench (Figure 11). Hazel is<br />

the principal species in four <strong>of</strong> the samples (238, 241, 242, 254) indicating that it may be the<br />

remains <strong>of</strong> wattle burnt in situ. In contrast, other samples from the wall trench (S201 <strong>and</strong><br />

S213) are composed <strong>of</strong> a mixture <strong>of</strong> pomaceous fruitwood <strong>and</strong> willow which could also<br />

represent in situ wattle burning. A sample from a further foundation trench (S226) is also<br />

dominated by hazel, while alder only was identified from posthole S255. This may be the<br />

remains <strong>of</strong> an alder post burnt in situ.<br />

In comparison to S255, a sample <strong>of</strong> burnt timbers (S236) was identified as alder only,<br />

suggesting it may have been used in construction also.<br />

Well preserved roundwoods were observed in S242. It was possible in one instance to<br />

measure the ring widths on a hazel roundwood which is 22mm in diameter (Plate 2). This<br />

32

piece was 17 years old when cut, bark still remains. Ring width measurements indicate that<br />

the roundwood had medium to fast rate <strong>of</strong> growth for the first few years <strong>of</strong> its life,<br />

particularly in rings 2-6 (from the pith outwards, yellow arrow). Subsequently, growth<br />

declines (Figure 12a). The fastest rate <strong>of</strong> growth is 2.2mm per annum in Year 2. It may be<br />

that the tree was in a st<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> other hazel trees <strong>of</strong> similar age, which then had to compete<br />

for light <strong>and</strong> nutrients as the shoots grew together.<br />

Plate 2 Hazel roundwood from S242 E109<br />

33

Growth <strong>of</strong> hazel S242<br />

2.5<br />

2<br />

growth (mm)<br />

1.5<br />

1<br />

0.5<br />

0<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17<br />

years<br />

Figure 12A<br />

Oak <strong>and</strong> willow were identified from under the stone setting <strong>of</strong> a central flag (S246), while<br />

oak only was identified beneath central flagging (S247). A sample <strong>of</strong> flint was noted to<br />

contain burnt wood, which was identified as alder, birch, ash, holly, oak <strong>and</strong> willow (S252). A<br />

sample <strong>of</strong> burnt wood was taken from the entrance trench (to the roundhouse?) oak only<br />

was identified from this, indicating some sort <strong>of</strong> a structural element (S272). A sample from<br />

between the upper <strong>and</strong> lower level <strong>of</strong> paving stones contained mainly alder, along with<br />

pomaceous fruitwood <strong>and</strong> willow (S900).<br />

fragment count<br />

100%<br />

80%<br />

60%<br />

40%<br />

20%<br />

0%<br />

S319 B2P<br />

S320 B2P<br />

Figure 13 Charcoal from midden contexts B2P & B2T<br />

Two discrete midden deposits were excavated at Belderg Beg, B2P <strong>and</strong> B2T. Both have been<br />

independently dated to the Early <strong>Bronze</strong> <strong>Age</strong>. Charcoal was identified from sixteen contexts<br />

34<br />

S321 B2P<br />

S322 B2P<br />

S323 B2P<br />

S324 BTP<br />

S325 B2P<br />

S326 B2P<br />

S327 B2P<br />

S328 B2P<br />

S329 B2P<br />

S330 B2P<br />

S331 B2P<br />

S332 B2P<br />

S901 B2P<br />

S902 B2P<br />

S235 B2T<br />

S256 B2T<br />

S258 B2T<br />

S257 B2T<br />

S277 B2T<br />

Salix<br />

Quercus<br />

Maloideae<br />

Ilex<br />

Fraxinus<br />

Corylus<br />

Betula<br />

Alnus

elating to midden B2P <strong>and</strong> from five contexts relating to middle B2T. Figure 13<br />

demonstrates that almost all <strong>of</strong> the B2P contexts have a very homogenous mix <strong>of</strong> birch <strong>and</strong><br />

alder (with the exception <strong>of</strong> S328). This is quite different from the samples from B2T, which<br />

mainly contain oak <strong>and</strong> hazel. The charcoal data does not indicate that B2P <strong>and</strong> B2T are the<br />

same deposit.<br />

Annual ring counts range from 2-33 in the Belderg beg samples. Ring curvature is a mixture<br />

between strongly <strong>and</strong> weakly curved, indicating the burning <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> sized material.<br />

Growth is medium to mixed.<br />

Wood results<br />

Twenty wooden posts were examined from Belderg Beg which had been preserved through<br />

waterlogging. Subsequent drying <strong>of</strong> the wood made it difficult to record any detail except<br />

the wood taxa. Fifteen <strong>of</strong> these were identified as oak, including samples 293, 295, 296 <strong>and</strong><br />

297 from Cutting C (Table 7). It is likely that these timbers represent fence posts <strong>and</strong> possibly<br />

building material. Oak is a strong <strong>and</strong> durable material, therefore it is unsurprising that it<br />

was selected for building at Belderg Beg. One willow post was also identified (S1151).<br />

fragment count<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

EBA<br />

MBA<br />

Salix<br />