web_vol47 4.pdf - International Hospital Federation

web_vol47 4.pdf - International Hospital Federation

web_vol47 4.pdf - International Hospital Federation

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Policy: China<br />

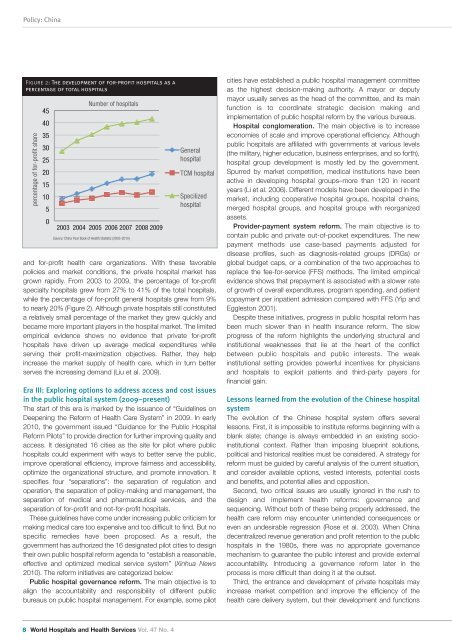

Figure 2: The development of for-profit hospitals as a<br />

percentage of total hospitals<br />

percentage of for-profit share<br />

45<br />

40<br />

35<br />

30<br />

25<br />

20<br />

15<br />

10<br />

5<br />

0<br />

Number of hospitals<br />

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009<br />

Source: China Year Book of Health Statistic (2003-2010)<br />

General<br />

hospital<br />

TCM hospital<br />

Specilized<br />

hospital<br />

and for-profit health care organizations. With these favorable<br />

policies and market conditions, the private hospital market has<br />

grown rapidly. From 2003 to 2009, the percentage of for-profit<br />

specialty hospitals grew from 27% to 41% of the total hospitals,<br />

while the percentage of for-profit general hospitals grew from 9%<br />

to nearly 20% (Figure 2). Although private hospitals still constituted<br />

a relatively small percentage of the market they grew quickly and<br />

became more important players in the hospital market. The limited<br />

empirical evidence shows no evidence that private for-profit<br />

hospitals have driven up average medical expenditures while<br />

serving their profit-maximization objectives. Rather, they help<br />

increase the market supply of health care, which in turn better<br />

serves the increasing demand (Liu et al. 2009).<br />

Era III: Exploring options to address access and cost issues<br />

in the public hospital system (2009–present)<br />

The start of this era is marked by the issuance of “Guidelines on<br />

Deepening the Reform of Health Care System” in 2009. In early<br />

2010, the government issued “Guidance for the Public <strong>Hospital</strong><br />

Reform Pilots” to provide direction for further improving quality and<br />

access. It designated 16 cities as the site for pilot where public<br />

hospitals could experiment with ways to better serve the public,<br />

improve operational efficiency, improve fairness and accessibility,<br />

optimize the organizational structure, and promote innovation. It<br />

specifies four “separations”: the separation of regulation and<br />

operation, the separation of policy-making and management, the<br />

separation of medical and pharmaceutical services, and the<br />

separation of for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals.<br />

These guidelines have come under increasing public criticism for<br />

making medical care too expensive and too difficult to find. But no<br />

specific remedies have been proposed. As a result, the<br />

government has authorized the 16 designated pilot cities to design<br />

their own public hospital reform agenda to “establish a reasonable,<br />

effective and optimized medical service system” (Xinhua News<br />

2010). The reform initiatives are categorized below:<br />

Public hospital governance reform. The main objective is to<br />

align the accountability and responsibility of different public<br />

bureaus on public hospital management. For example, some pilot<br />

cities have established a public hospital management committee<br />

as the highest decision-making authority. A mayor or deputy<br />

mayor usually serves as the head of the committee, and its main<br />

function is to coordinate strategic decision making and<br />

implementation of public hospital reform by the various bureaus.<br />

<strong>Hospital</strong> conglomeration. The main objective is to increase<br />

economies of scale and improve operational efficiency. Although<br />

public hospitals are affiliated with governments at various levels<br />

(the military, higher education, business enterprises, and so forth),<br />

hospital group development is mostly led by the government.<br />

Spurred by market competition, medical institutions have been<br />

active in developing hospital groups–more than 120 in recent<br />

years (Li et al. 2006). Different models have been developed in the<br />

market, including cooperative hospital groups, hospital chains,<br />

merged hospital groups, and hospital groups with reorganized<br />

assets.<br />

Provider-payment system reform. The main objective is to<br />

contain public and private out-of-pocket expenditures. The new<br />

payment methods use case-based payments adjusted for<br />

disease profiles, such as diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) or<br />

global budget caps, or a combination of the two approaches to<br />

replace the fee-for-service (FFS) methods. The limited empirical<br />

evidence shows that prepayment is associated with a slower rate<br />

of growth of overall expenditures, program spending, and patient<br />

copayment per inpatient admission compared with FFS (Yip and<br />

Eggleston 2001).<br />

Despite these initiatives, progress in public hospital reform has<br />

been much slower than in health insurance reform. The slow<br />

progress of the reform highlights the underlying structural and<br />

institutional weaknesses that lie at the heart of the conflict<br />

between public hospitals and public interests. The weak<br />

institutional setting provides powerful incentives for physicians<br />

and hospitals to exploit patients and third-party payers for<br />

financial gain.<br />

Lessons learned from the evolution of the Chinese hospital<br />

system<br />

The evolution of the Chinese hospital system offers several<br />

lessons. First, it is impossible to institute reforms beginning with a<br />

blank slate; change is always embedded in an existing socioinstitutional<br />

context. Rather than imposing blueprint solutions,<br />

political and historical realities must be considered. A strategy for<br />

reform must be guided by careful analysis of the current situation,<br />

and consider available options, vested interests, potential costs<br />

and benefits, and potential allies and opposition.<br />

Second, two critical issues are usually ignored in the rush to<br />

design and implement health reforms: governance and<br />

sequencing. Without both of these being properly addressed, the<br />

health care reform may encounter unintended consequences or<br />

even an undesirable regression (Rose et al. 2003). When China<br />

decentralized revenue generation and profit retention to the public<br />

hospitals in the 1980s, there was no appropriate governance<br />

mechanism to guarantee the public interest and provide external<br />

accountability. Introducing a governance reform later in the<br />

process is more difficult than doing it at the outset.<br />

Third, the entrance and development of private hospitals may<br />

increase market competition and improve the efficiency of the<br />

health care delivery system, but their development and functions<br />

8 World <strong>Hospital</strong>s and Health Services Vol. 47 No. 4