web_vol47 4.pdf - International Hospital Federation

web_vol47 4.pdf - International Hospital Federation

web_vol47 4.pdf - International Hospital Federation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Policy: China<br />

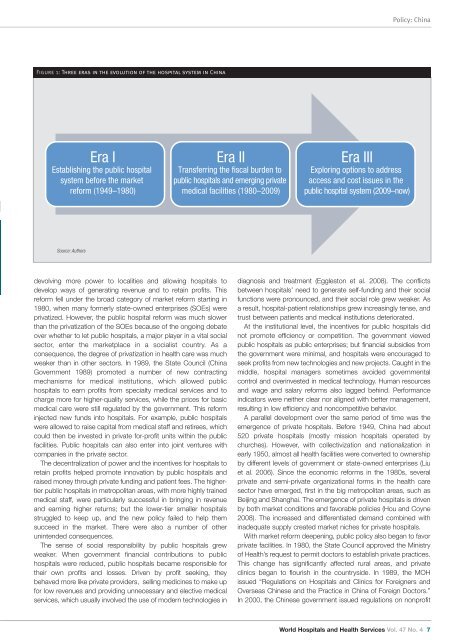

Figure 1: Three eras in the evolution of the hospital system in China<br />

Era I<br />

Establishing the public hospital<br />

system before the market<br />

reform (1949–1980)<br />

Era II<br />

Transferring the fiscal burden to<br />

public hospitals and emerging private<br />

medical facilities (1980–2009)<br />

Era III<br />

Exploring options to address<br />

access and cost issues in the<br />

public hospital system (2009–now)<br />

Source: Authors<br />

devolving more power to localities and allowing hospitals to<br />

develop ways of generating revenue and to retain profits. This<br />

reform fell under the broad category of market reform starting in<br />

1980, when many formerly state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were<br />

privatized. However, the public hospital reform was much slower<br />

than the privatization of the SOEs because of the ongoing debate<br />

over whether to let public hospitals, a major player in a vital social<br />

sector, enter the marketplace in a socialist country. As a<br />

consequence, the degree of privatization in health care was much<br />

weaker than in other sectors. In 1989, the State Council (China<br />

Government 1989) promoted a number of new contracting<br />

mechanisms for medical institutions, which allowed public<br />

hospitals to earn profits from specialty medical services and to<br />

charge more for higher-quality services, while the prices for basic<br />

medical care were still regulated by the government. This reform<br />

injected new funds into hospitals. For example, public hospitals<br />

were allowed to raise capital from medical staff and retirees, which<br />

could then be invested in private for-profit units within the public<br />

facilities. Public hospitals can also enter into joint ventures with<br />

companies in the private sector.<br />

The decentralization of power and the incentives for hospitals to<br />

retain profits helped promote innovation by public hospitals and<br />

raised money through private funding and patient fees. The highertier<br />

public hospitals in metropolitan areas, with more highly trained<br />

medical staff, were particularly successful in bringing in revenue<br />

and earning higher returns; but the lower-tier smaller hospitals<br />

struggled to keep up, and the new policy failed to help them<br />

succeed in the market. There were also a number of other<br />

unintended consequences.<br />

The sense of social responsibility by public hospitals grew<br />

weaker. When government financial contributions to public<br />

hospitals were reduced, public hospitals became responsible for<br />

their own profits and losses. Driven by profit seeking, they<br />

behaved more like private providers, selling medicines to make up<br />

for low revenues and providing unnecessary and elective medical<br />

services, which usually involved the use of modern technologies in<br />

diagnosis and treatment (Eggleston et al. 2008). The conflicts<br />

between hospitals’ need to generate self-funding and their social<br />

functions were pronounced, and their social role grew weaker. As<br />

a result, hospital-patient relationships grew increasingly tense, and<br />

trust between patients and medical institutions deteriorated.<br />

At the institutional level, the incentives for public hospitals did<br />

not promote efficiency or competition. The government viewed<br />

public hospitals as public enterprises; but financial subsidies from<br />

the government were minimal, and hospitals were encouraged to<br />

seek profits from new technologies and new projects. Caught in the<br />

middle, hospital managers sometimes avoided governmental<br />

control and overinvested in medical technology. Human resources<br />

and wage and salary reforms also lagged behind. Performance<br />

indicators were neither clear nor aligned with better management,<br />

resulting in low efficiency and noncompetitive behavior.<br />

A parallel development over the same period of time was the<br />

emergence of private hospitals. Before 1949, China had about<br />

520 private hospitals (mostly mission hospitals operated by<br />

churches). However, with collectivization and nationalization in<br />

early 1950, almost all health facilities were converted to ownership<br />

by different levels of government or state-owned enterprises (Liu<br />

et al. 2006). Since the economic reforms in the 1980s, several<br />

private and semi-private organizational forms in the health care<br />

sector have emerged, first in the big metropolitan areas, such as<br />

Beijing and Shanghai. The emergence of private hospitals is driven<br />

by both market conditions and favorable policies (Hou and Coyne<br />

2008). The increased and differentiated demand combined with<br />

inadequate supply created market niches for private hospitals.<br />

With market reform deepening, public policy also began to favor<br />

private facilities. In 1980, the State Council approved the Ministry<br />

of Health’s request to permit doctors to establish private practices.<br />

This change has significantly affected rural areas, and private<br />

clinics began to flourish in the countryside. In 1989, the MOH<br />

issued “Regulations on <strong>Hospital</strong>s and Clinics for Foreigners and<br />

Overseas Chinese and the Practice in China of Foreign Doctors.”<br />

In 2000, the Chinese government issued regulations on nonprofit<br />

World <strong>Hospital</strong>s and Health Services Vol. 47 No. 4 7