Moravian Preservation Master Plan.indb - Society for College and ...

Moravian Preservation Master Plan.indb - Society for College and ...

Moravian Preservation Master Plan.indb - Society for College and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

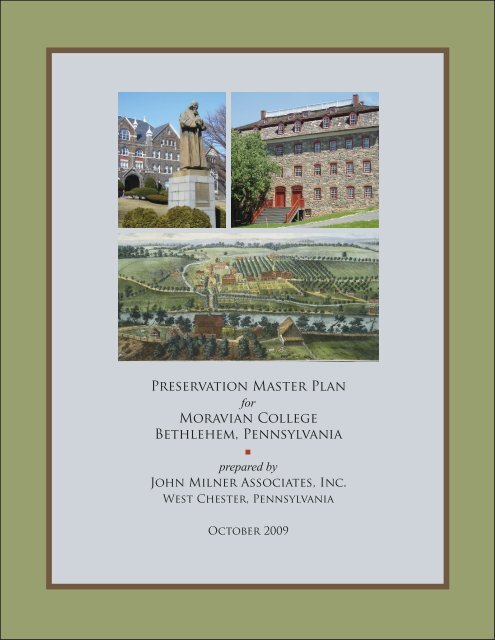

<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania<br />

prepared by<br />

John Milner Associates, Inc.<br />

West Chester, Pennsylvania<br />

October 2009

<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania<br />

Prepared by<br />

JMA<br />

John Milner Associates, Inc.<br />

535 North Church Street<br />

West Chester, Pennsylvania 19380<br />

Project Team<br />

Katherine L. Farnham — Project Architectural Historian/Project Manager<br />

Laura Knott, ASLA, RLA — Principal L<strong>and</strong>scape Architect<br />

Christina Osborn, Associate ASLA — L<strong>and</strong>scape Architectural Designer<br />

Lori Aument, LEED-AP — Architectural Conservator<br />

Wade Catts, RPA — Principal Archeologist<br />

Thomas Scofield, AICP — Principal <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ner<br />

Peter Benton, FAIA — Project Director<br />

October 2009

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Prepared For<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania<br />

Project Advisory Committee<br />

Dr. Hilde Bin<strong>for</strong>d — Associate Professor of Music<br />

Mr. Blair Flintom — Facilities Coordinator, Priscilla Payne Hurd Campus<br />

Mr. Douglas J. Plotts — Director of Facilities Management, <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>and</strong> Construction<br />

Ms. Sue Schamberger — Director of Foundation Relations<br />

Dr. Carol Traupman-Carr — Associate Dean <strong>for</strong> Academic Affairs<br />

The JMA project team would like to acknowledge the insight, documents, photos, <strong>and</strong> other assistance<br />

provided by Ms. Sue Schamberger, Director of Foundation Relations at <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong>.<br />

Funded By<br />

J. Paul Getty Trust<br />

Getty Campus Heritage Grant<br />

October 2009<br />

When citing this report, please use Farnham, Katherine, Laura Knott, Christina Osborn, Lori Aument,<br />

Wade Catts, Thomas Scofield, <strong>and</strong> Peter Benton (Farnham et al.), <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong> (2009).<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Acknowledgements • iii

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

Chapter 1 • Introduction<br />

1.0 Introduction 1<br />

1.1 Project Background <strong>and</strong> Purpose 1<br />

Methodology 1<br />

Project Personnel 2<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Issues 2<br />

1.2 How to Use the Guidelines 2<br />

1.3 How the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> Is Organized 4<br />

Chapter 2 • Historic Overview of <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

2.0 Introduction 5<br />

2.1 Bethlehem: <strong>Moravian</strong> Capital to Industrial Giant 5<br />

Natural <strong>and</strong> Scenic Qualities of Bethlehem 5<br />

Roots of <strong>Moravian</strong> Faith 5<br />

Beginnings of Bethlehem 7<br />

Bethlehem: The Eighteenth Century 9<br />

End of the <strong>Moravian</strong> Economy 1762-1770 10<br />

The Buildings of Early Bethlehem 1742-1770 11<br />

Bethlehem from 1770–1800 13<br />

Urbanization of Bethlehem 1790-1850 14<br />

Industrial Bethlehem 15<br />

Twentieth Century Bethlehem 17<br />

2.2 Education in the <strong>Moravian</strong> Tradition 18<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Educational Philosophy 18<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> Female Seminary 18<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>and</strong> Theological Seminary 24<br />

Merger of Two Institutions 28<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> Campus Expansion: 1956-1978 29<br />

2.3 Historic <strong>Preservation</strong> in Bethlehem 31<br />

2.4 <strong>Moravian</strong>’s Recent Years 32<br />

2.5 Conclusion 33<br />

Chapter 3 • <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> in Context<br />

3.0 Introduction 35<br />

3.1 Community <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>and</strong> Development 35<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Settlements in North America 35<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Bethlehem 36<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> Mile: Growth <strong>and</strong> Development of the North Main Street Neighborhood 39<br />

3.2 <strong>Moravian</strong> Beliefs <strong>and</strong> Educational Principles 40<br />

3.3 Nature <strong>and</strong> Nurture: Nineteenth Century Campus <strong>Plan</strong>ning 40<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Table of Contents • v

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Seminary <strong>for</strong> Young Ladies 41<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>and</strong> Theological Seminary 43<br />

3.4 The New University – Specialization <strong>and</strong> Modernization 44<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>and</strong> Theological Seminary 44<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Seminary <strong>for</strong> Young Ladies 46<br />

3.5 Postwar Modernism 46<br />

Merger <strong>and</strong> Modern Needs 47<br />

3.6 Postmodernism 48<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong>: A Postmodern Vocabulary 48<br />

3.7 <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Historic <strong>Preservation</strong> of Bethlehem 49<br />

Chapter 4 • Stewardship at <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

4.0 Introduction 53<br />

4.1 <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong>: Mission <strong>and</strong> Character 53<br />

4.2 Vision <strong>for</strong> Stewardship 54<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Objectives 54<br />

4.3 Historical Significance 54<br />

Significance 54<br />

Integrity 56<br />

Existing Conditions 56<br />

4.4 Historic Designation 57<br />

Priscilla Payne Hurd Campus 57<br />

North Main Street Campus 57<br />

4.5 <strong>Preservation</strong> Treatments <strong>and</strong> the Secretary of the Interior’s St<strong>and</strong>ards 58<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> 58<br />

Rehabilitation 59<br />

Restoration 60<br />

Reconstruction 61<br />

4.6 A Treatment Philosophy <strong>and</strong> Recommended Approach <strong>for</strong> <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> 62<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>for</strong> Rehabilitation 63<br />

4.7 Principles <strong>for</strong> Accommodating Change 67<br />

Chapter 5 • Cultural L<strong>and</strong>scapes at <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

5.0 Introduction 69<br />

5.1 Methodology 69<br />

5.2 Context <strong>and</strong> Setting 69<br />

City of Bethlehem 71<br />

5.4 Character Areas 72<br />

Hurd Campus Character Area 73<br />

Steel Field Character Area 94<br />

Comenius Lawn Character Area 99<br />

Old Quad Character Area 107<br />

Monocacy Quad Character Area 112<br />

Colonial Hall Character Area 116<br />

Sports Quad Character Area 121<br />

Hillside Character Area 127<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Table of Contents • vi

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Betty Prince Field Character Area 130<br />

Campus Ring Character Area 133<br />

5.5 Significant Historic L<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> their Character-Defining Features 138<br />

Table 5A. Significant Historic L<strong>and</strong>scapes 139<br />

Table 5B. Other L<strong>and</strong>scapes of Note 141<br />

Chapter 6 • Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Cultural L<strong>and</strong>scapes<br />

6.0 Introduction 143<br />

6.1 L<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>Preservation</strong> Treatment Approach 143<br />

6.2 Cultural L<strong>and</strong>scape Guidelines 143<br />

General 143<br />

Natural Systems <strong>and</strong> Features 144<br />

Spatial Organization 145<br />

Buildings 145<br />

L<strong>and</strong> Use 145<br />

Circulation Features 145<br />

Views <strong>and</strong> Vistas 147<br />

Vegetation 147<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape Structures 150<br />

Site Furnishings <strong>and</strong> Objects 151<br />

Archeological Resources 154<br />

Chapter 7 • Character Area Treatment Recommendations<br />

7.0 Introduction 155<br />

7.1 Character Area Treatment Recommendations 155<br />

Hurd Campus Character Area 155<br />

Steel Field Character Area 160<br />

Comenius Lawn Character Area 161<br />

Old Quad Character Area 164<br />

Monocacy Quad Character Area 167<br />

Colonial Hall Character Area 169<br />

Sports Quad Character Area 170<br />

Hillside Character Area 171<br />

Betty Prince Field Character Area 171<br />

Campus Ring Character Area 171<br />

Chapter 8 • Historic Buildings at <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

8.0 Introduction 173<br />

8.1 Priscilla Payne Hurd Campus Buildings 173<br />

The Single Brethren’s House – 1748 174<br />

West Hall – 1859 181<br />

Hyphen Addition – ca. 1859 187<br />

Old Chapel Building/Hearst Hall – 1848 188<br />

New Chapel/Peter Hall – 1867 192<br />

South Hall – 1873 197<br />

Payne Art Gallery – 1890 203<br />

Day House – 1840 207<br />

Main Hall – 1854 209<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Table of Contents • vii

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

John Frederick Frueauff House – 1819 214<br />

Widows’ House – 1768 217<br />

Clewell Hall – 1867 223<br />

8.2 Steel Field 226<br />

Gr<strong>and</strong>st<strong>and</strong> – 1916 226<br />

8.3 North Main Street Campus 230<br />

Comenius Hall – 1891 230<br />

Hamilton Hall – 1820 241<br />

Zinzendorf Hall – 1891 246<br />

Monocacy Hall – 1913 252<br />

Memorial Hall – 1923 257<br />

Johnston Hall – 1952 262<br />

Colonial Hall – 1930 265<br />

Other Buildings 270<br />

8.4 Campus Ring 270<br />

8.5 Overall Conditions – Key <strong>Preservation</strong> Issues 274<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Issue #1 – Masonry 274<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Issue #2 – Windows 276<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Issue #3 – Roofs <strong>and</strong> Roofing 277<br />

Chapter 9 • Treatment Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Buildings<br />

9.0 Introduction 279<br />

Applying the Secretary of the Interior’s St<strong>and</strong>ards 279<br />

9.1 Site Drainage 280<br />

Typical Site Drainage Conditions 280<br />

Site Drainage Inspection 280<br />

Causes of Site Drainage Deterioration 280<br />

Site Drainage Improvements 281<br />

9.2 Concrete 281<br />

Typical Concrete Conditions 281<br />

Concrete Inspection 282<br />

Causes of Concrete Deterioration 282<br />

Concrete Repair <strong>and</strong> Replacement 283<br />

9.3 Masonry 283<br />

Stone 283<br />

Brick 284<br />

Typical Masonry Conditions 284<br />

Masonry Inspection 284<br />

Causes of Masonry Deterioration 285<br />

Masonry Repair 287<br />

Replication Mortar Mixes 291<br />

Good Repointing Practice 292<br />

Masonry Replacement 292<br />

9.4 Metals 293<br />

Typical Metal Conditions 293<br />

Metal Inspection 293<br />

Causes of Metal Deterioration 293<br />

Metal Repair 293<br />

Metal Replacement 293<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Table of Contents • viii

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

9.5 Exterior <strong>and</strong> Structural Wood 294<br />

Typical Wood Conditions 294<br />

Wood Inspection 294<br />

Causes of Wood Deterioration 295<br />

Wood Repair 296<br />

Wood Replacement 297<br />

9.6 Roofs <strong>and</strong> Drainage Systems 298<br />

Typical Roof <strong>and</strong> Roof Drainage System Conditions 299<br />

Roof <strong>and</strong> Roof Drainage System Inspection 299<br />

Roof <strong>and</strong> Roof Drainage System Repair 300<br />

Rooftop Additions <strong>and</strong> Attachments 302<br />

Roof Replacement or Alteration 302<br />

Roof Insulation 303<br />

9.7 Doors 303<br />

Typical Door Conditions 303<br />

Door Inspection <strong>and</strong> Maintenance 303<br />

Causes of Door Deterioration 304<br />

Door Repair 304<br />

Door Replacement or Reconstruction 304<br />

9.8 Windows 305<br />

Typical Window Conditions 305<br />

Window Inspection <strong>and</strong> Maintenance 305<br />

Causes of Window Deterioration 305<br />

Window Repair 306<br />

Window Weatherization 306<br />

Window Replacement <strong>and</strong> Alteration 307<br />

9.9 Stucco 309<br />

Typical Stucco Conditions 309<br />

Stucco Inspection 309<br />

Causes of Stucco Deterioration 309<br />

Stucco Repair <strong>and</strong> Replacement 309<br />

9.10 Paint 310<br />

Paint Inspection <strong>and</strong> Maintenance 310<br />

Repair <strong>and</strong> Repainting 311<br />

Historic Paint Colors 312<br />

9.11 Interiors 312<br />

Typical Conditions 313<br />

Inspection 313<br />

Causes of Deterioration 313<br />

Repair <strong>and</strong> Renovation 314<br />

Chapter 10 • Guidelines <strong>for</strong> New Construction <strong>and</strong> Alterations<br />

10.0 Introduction 315<br />

Existing Administrative Procedures 315<br />

10.1 Administrative <strong>and</strong> Management Recommendations 316<br />

General Recommendations 316<br />

Guidelines <strong>for</strong> New Construction 319<br />

Guidelines <strong>for</strong> Rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> Adaptive Use 321<br />

Recommendations <strong>for</strong> Energy Conservation <strong>and</strong> New Building Systems 322<br />

Recommendations <strong>for</strong> Sustainable Design 324<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Table of Contents • ix

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Recommendations <strong>for</strong> Barrier-Free Access 327<br />

References Cited 329<br />

Appendix A • 1968 HABS Documentation of the Single Brethren’s House 335<br />

Appendix B • National Park Service Technical Publications 383<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Briefs 383<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Tech Notes 391<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Table of Contents • x

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Chapter One<br />

Introduction<br />

1.0 Introduction<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> is among the oldest colleges<br />

in the United States. Its historical significance<br />

spans nearly three centuries <strong>and</strong> represents a<br />

diverse array of social, religious, <strong>and</strong> architectural<br />

influences. Present-day <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> retains<br />

its historical emphasis on intellectual curiosity,<br />

personal integrity, community cohesiveness, <strong>and</strong><br />

strengths in music <strong>and</strong> the fine arts, a rich tradition<br />

of excellence h<strong>and</strong>ed down from the strong faith,<br />

values, scholarship, music <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong>icrafts of the<br />

eighteenth-century <strong>Moravian</strong> community.<br />

The historic buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape resources on<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong>’s two campuses were built by<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong>s of different generations, but most derive<br />

from distinct European roots <strong>and</strong> community<br />

patterns established long ago. American design<br />

trends, educational beliefs, <strong>and</strong> cultural influences<br />

have combined with <strong>Moravian</strong> culture <strong>and</strong> European<br />

vernacular architecture to <strong>for</strong>m campuses of<br />

unique historic character. Generations of students:<br />

young girls, college men <strong>and</strong> women, <strong>and</strong> theology<br />

students have been educated here. The <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

Church <strong>and</strong> generations of administrators, faculty,<br />

employees, alumni, <strong>and</strong> benefactors have helped to<br />

shape the school into the campuses we see today<br />

(figure 1-1).<br />

This preservation master plan explores the physical<br />

connections between the <strong>College</strong>’s past <strong>and</strong> present.<br />

As <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> continues to exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

evolve, it is important to recognize <strong>and</strong> preserve<br />

those aspects of its history that have helped define<br />

its character <strong>and</strong> identity. It is equally important to<br />

identify <strong>and</strong> celebrate those aspects of its history<br />

that can help guide its future.<br />

1.1 Project Background <strong>and</strong><br />

Purpose<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> has long recognized the<br />

importance of its history <strong>and</strong> the quality of its<br />

physical character. The image of the <strong>College</strong>, which<br />

is in large part the image of its historic buildings<br />

<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape, is meaningful <strong>and</strong> important to<br />

students, faculty, staff, <strong>and</strong> alumni, as well as to<br />

local residents <strong>and</strong> the general public. In early<br />

2008, <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> was awarded a generous<br />

grant from the J. Paul Getty Trust through its Getty<br />

Campus Heritage Grant program. The purpose of<br />

the grant was to create a <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> the <strong>College</strong>’s campus. John Milner Associates,<br />

Inc. (JMA) was retained to prepare the <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>and</strong> began work in<br />

the early summer of 2008. An Advisory Committee,<br />

comprised of <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> faculty <strong>and</strong> staff,<br />

was <strong>for</strong>med to review the work being done.<br />

Methodology<br />

The planning process began with the collection<br />

of data <strong>and</strong> background materials on <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong>’s history. Books, clippings, old <strong>College</strong><br />

publications, historic maps, plans <strong>and</strong> photographs<br />

were among the items reviewed during research.<br />

These materials were reviewed through the Office<br />

of Development, Facilities, <strong>and</strong> the Reeves Library<br />

Archives at <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

Church Archives.<br />

The JMA project team then conducted field<br />

investigations of the historic buildings <strong>and</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes of the dual campuses, taking notes<br />

<strong>and</strong> digital photographs. Utilizing the historical<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation found in the data review, the team<br />

identified the resources <strong>and</strong> assessed the character,<br />

condition, significance, <strong>and</strong> integrity of each built<br />

resource or l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

Once the existing conditions had been reviewed<br />

<strong>and</strong> analyzed, the focus turned to developing a<br />

preservation approach in concert with <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong>’s stated mission <strong>and</strong> goals. Using<br />

the Secretary of the Interior’s St<strong>and</strong>ards, the<br />

team recommended both general <strong>and</strong> specific<br />

treatments <strong>for</strong> historic buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes,<br />

<strong>and</strong> developing guidelines to aid in future work<br />

processes affecting <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong>’s historic<br />

resources, including guidance <strong>for</strong> new construction<br />

<strong>and</strong> maintenance cycles.<br />

Draft versions of the history, stewardship, existing<br />

conditions, <strong>and</strong> treatment recommendations<br />

<strong>and</strong> guidelines were presented <strong>and</strong> reviewed<br />

by the Advisory Committee. Following review<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 1 • Introduction • 1

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> feedback, the consultants prepared the final<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>.<br />

Project Personnel<br />

Peter C. Benton served as Project Director <strong>and</strong><br />

Katherine Farnham served as Project Manager <strong>for</strong><br />

the <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>. Ms.<br />

Farnham also prepared the historic overview <strong>and</strong><br />

context <strong>and</strong> wrote <strong>and</strong> edited much of the report<br />

text. L<strong>and</strong>scape existing conditions assessment,<br />

historic l<strong>and</strong>scape treatment recommendations,<br />

<strong>and</strong> all project maps were prepared by Christina<br />

Osborn <strong>and</strong> Laura Knott. Ms. Osborn also compiled<br />

<strong>and</strong> prepared the report. Wade Catts provided<br />

archeological analysis as part of the l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

evaluation. Architectural existing conditions<br />

assessment of <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong>’s buildings <strong>and</strong><br />

recommendations <strong>for</strong> treatment were completed<br />

by Lori Aument, Peter Benton, Katherine Farnham,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Thomas Scofield.<br />

The <strong>College</strong> will receive hard <strong>and</strong> electronic copies<br />

of the final document so it is readily available <strong>for</strong><br />

distribution to the <strong>College</strong> community <strong>and</strong> beyond.<br />

An electronic version of the document will be made<br />

available to the general public by inclusion on the<br />

<strong>College</strong> website.<br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> Issues<br />

Overall, <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> possesses a distinctive<br />

collection of historic buildings <strong>and</strong> surrounding<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scapes. While there is some variation in<br />

the historic significance, physical integrity, <strong>and</strong><br />

overall conditions of the buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes,<br />

some common preservation issues are apparent<br />

throughout the campus.<br />

Buildings:<br />

• Need <strong>for</strong> ongoing <strong>and</strong> preventive<br />

maintenance.<br />

• Need <strong>for</strong> historically appropriate<br />

maintenance.<br />

• Historical integrity of building exteriors.<br />

• Appropriateness <strong>and</strong> functionality of<br />

interior treatments.<br />

• ADA accessibility.<br />

• Installation <strong>and</strong> upgrading of building<br />

systems (mechanical, fire safety,<br />

technology, HVAC, etc.).<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scapes:<br />

• Need <strong>for</strong> ongoing <strong>and</strong> preventive<br />

maintenance.<br />

• Need <strong>for</strong> historically appropriate design.<br />

• Historical integrity of features <strong>and</strong><br />

characteristics.<br />

• High archeological sensitivity in the Hurd<br />

Campus.<br />

• Appropriateness of previous changes in<br />

the l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

1.2 How to Use the<br />

Guidelines<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is<br />

intended to be a reference resource <strong>and</strong> a guide to<br />

the ongoing stewardship of the <strong>College</strong>’s historic<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes. It takes a broad view<br />

of the <strong>College</strong>’s history <strong>and</strong> physical character to<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> how the <strong>College</strong> sees itself <strong>and</strong> how<br />

it has chosen to accommodate change over time.<br />

Out of this view, the plan provides guidance <strong>for</strong><br />

decision making about the future, recommending<br />

strategies <strong>and</strong> priorities <strong>for</strong> preserving significant<br />

historic resources <strong>and</strong> using those resources to<br />

enhance the <strong>College</strong>’s character as change occurs.<br />

The preservation plan outlines a set of basic<br />

preservation principles <strong>and</strong> explains how they can<br />

be intelligently applied to the <strong>College</strong>’s historic<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes. Every building <strong>and</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape presents unique issues <strong>and</strong> opportunities,<br />

<strong>and</strong> every campus project is different. Without a set<br />

of guidelines to follow, it can be difficult to identify<br />

all of the issues that might arise in a maintenance,<br />

repair, or construction project.<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> will<br />

help the <strong>College</strong> manage change in ways that<br />

recognize <strong>and</strong> preserve significant building <strong>and</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape resources. Along with being a planning<br />

document, the preservation plan is a chronicle<br />

of the <strong>College</strong>’s physical development up to this<br />

point, presenting an existing-conditions snapshot<br />

that will <strong>for</strong>m a background reference <strong>and</strong> basis <strong>for</strong><br />

comparison during future planning initiatives.<br />

In undertaking preparation of the <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>, existing historic resources<br />

were reviewed, character-defining features were<br />

identified, <strong>and</strong> treatments were recommended.<br />

Design guidelines <strong>for</strong> the appropriate treatment of<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 1 • Introduction • 2

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

historic fabric <strong>and</strong> building <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape features<br />

are included in the document.<br />

The chapters in this document are essentially a<br />

checklist of items that should be considered when<br />

contemplating change to the <strong>College</strong>’s historic<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scapes. When new projects are<br />

proposed, it is recommended that the preservation<br />

plan be consulted as early in the process as possible<br />

so that the ideas <strong>and</strong> guidelines provided will<br />

reach their maximum effectiveness. The principles<br />

outlined here are intended to provide a strong<br />

philosophical foundation but to be flexible <strong>and</strong><br />

adaptable to changing needs <strong>and</strong> circumstances.<br />

Design guidelines can often inspire creative <strong>and</strong><br />

sensitive solutions that were not envisioned when<br />

a project was first proposed. The best outcomes are<br />

those that meet the needs of the <strong>College</strong>’s academic<br />

<strong>and</strong> residential programs while preserving the<br />

elements that define historic building <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>scape<br />

character.<br />

Figure 1-1. <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> is located on separate campuses within the City of Bethlehem, PA (United States Geological Survey,<br />

annotated by JMA 2009).<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 1 • Introduction • 3

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

1.3 How the <strong>Preservation</strong><br />

<strong>Plan</strong> Is Organized<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is<br />

divided into ten chapters. The preservation plan<br />

begins with a historic overview <strong>and</strong> a chapter<br />

placing the <strong>College</strong> into larger historic contexts.<br />

Next is a chapter on stewardship, which introduces<br />

federal preservation st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> outlines the<br />

proposed preservation approach <strong>for</strong> <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong>. This is followed by a review of existing<br />

l<strong>and</strong>scape <strong>and</strong> building resources, including a<br />

summary of their significance, historical integrity,<br />

<strong>and</strong> existing conditions. The final chapters provide<br />

guidelines <strong>for</strong> treatment <strong>and</strong> maintenance of the<br />

<strong>College</strong>’s historic resources <strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong> compatible new<br />

construction.<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 1 • Introduction • 4

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Chapter Two<br />

Historic Overview of <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

2.0 Introduction<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> has a long <strong>and</strong> rich history. Closely<br />

intertwined with the establishment of Bethlehem<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Moravian</strong> theology <strong>and</strong> culture, today’s college<br />

is the descendant of two distinguished <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

educational institutions, which served both men<br />

<strong>and</strong> women over the course of two centuries be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

merging in 1954. The founders of these schools were<br />

also instrumental in the settlement <strong>and</strong> growth of<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Bethlehem. Though Bethlehem’s era as<br />

an exclusively <strong>Moravian</strong> settlement is long gone,<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>and</strong> its parent schools have<br />

perpetuated some of the <strong>Moravian</strong> faith’s most<br />

cherished educational <strong>and</strong> cultural values into<br />

the present day, <strong>and</strong> kept this legacy relevant to<br />

generations of students.<br />

2.1 Bethlehem: <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

Capital to Industrial Giant<br />

Natural <strong>and</strong> Scenic Qualities of<br />

Bethlehem<br />

The earliest part of Bethlehem, including the<br />

entirety of today’s Priscilla Payne Hurd Campus,<br />

st<strong>and</strong>s atop a bluff overlooking the confluence of<br />

the Lehigh River <strong>and</strong> Monocacy Creek. The site is<br />

part of the Great Valley, a large limestone <strong>for</strong>mation<br />

measuring eight to twelve miles in width, which<br />

curves north into New Jersey <strong>and</strong> south through<br />

Pennsylvania into Maryl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Virginia. The<br />

site is part of the Lehigh River drainage area. The<br />

Lehigh River flows eastward to the south of the<br />

bluff, <strong>and</strong> Monocacy Creek flows southward to<br />

the west of the project area (see figure 1-1). Bedrock<br />

beneath the city consists of medium-gray thickbedded<br />

dolomite <strong>and</strong> impure limestone calcareous<br />

siltstone at its base. Subsoil in the area is yellow to<br />

reddish-yellow clay (Gerhardt et al. 2008:4; National<br />

Heritage Corporation 1977:20).<br />

The site chosen <strong>for</strong> the city had a number of<br />

features attractive to the first settlers. Foremost was<br />

a plenteous spring at the base of the bluff, which<br />

would provide water in all seasons <strong>and</strong> was a<br />

primary reason <strong>for</strong> the purchase of this particular<br />

tract. The hillside was wooded with a steep descent<br />

to the river <strong>and</strong> creek. Monocacy Creek at that time<br />

flowed south along the west side of the future city<br />

<strong>and</strong> then turned toward the east, meeting the Lehigh<br />

River southeast of the town site <strong>and</strong> <strong>for</strong>ming a long<br />

east-west peninsula between the two waterways.<br />

On the south side of the Monocacy Creek peninsula<br />

was a <strong>for</strong>d across the Lehigh River. The new town<br />

was sited “some distance from the river” beside an<br />

old Native American trail that extended north <strong>and</strong><br />

west from the <strong>for</strong>d, crossing the peninsula <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Monocacy Creek, <strong>and</strong> running uphill past the new<br />

site (Murtagh 1967:23).<br />

Roots of <strong>Moravian</strong> Faith<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Christianity dates back to the fifteenth<br />

century, <strong>and</strong> had two distinct periods: the original<br />

Bohemian church, which was eventually driven<br />

underground, <strong>and</strong> the Renewed Church beginning<br />

in 1722 (Weinlick in Myers 1982:5). <strong>Moravian</strong>ism<br />

began in Bohemia <strong>and</strong> Moravia in central <strong>and</strong><br />

Eastern Europe (figure 2-1). This area was originally<br />

Christianized by the Eastern Orthodox branch of<br />

Catholicism, but eventually Roman Catholicism<br />

became the controlling denomination. Still, the<br />

Christians of these regions felt ties to the Eastern<br />

tradition <strong>and</strong> as such reacted strongly to the<br />

worldly corruption occurring within the Roman<br />

Catholic Church during the 1300s <strong>and</strong> 1400s. John<br />

Hus (born 1369), an instructor at the University of<br />

Prague, helped voice the sentiment that Christian<br />

belief <strong>and</strong> way of life derived from the Bible, not<br />

from the Pope <strong>and</strong> the church leadership hierarchy.<br />

Following his break with the Church, Hus was<br />

condemned as a heretic <strong>and</strong> burned at the stake in<br />

1415. His martyrdom sowed seeds of Protestantism<br />

among his community (Groenfeldt 1976:13).<br />

In the years following the death of Hus, his followers<br />

struggled with different perspectives but could not<br />

create a united community of believers. One faction<br />

separated itself in 1457, <strong>and</strong> was known as the<br />

Unity of the Brethren (Unitas Fratrum). The group’s<br />

primary goal was to avoid further religious conflict<br />

<strong>and</strong> live peacefully, following the teachings of the<br />

New Testament. Despite continued persecution,<br />

the denomination began to grow. During the Thirty<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 5

Figure 2-1. Detail of Map of Central Europe about 1547 (Shepherd 1926).<br />

Years’ War, Protestantism in Bohemia <strong>and</strong> Moravia<br />

was effectively quashed by the <strong>for</strong>ces of the Catholic<br />

Church, <strong>for</strong>cing adherents to either ab<strong>and</strong>on their<br />

faith or leave the country. Years of persecution,<br />

capped by the executions of 27 Bohemian <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> leaders on the Day of Blood, June 21,<br />

1621, caused thous<strong>and</strong>s of frightened Bohemian<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Moravian</strong> Protestants to flee from their home<br />

regions. Beginning in 1624, the Protestants were<br />

dispersed to safer regions, including Pol<strong>and</strong>,<br />

Silesia, Prussia, Saxony, <strong>and</strong> Upper Lusatia. Among<br />

them was a Unity group led to safety in Pol<strong>and</strong> by<br />

their bishop, John Amos Comenius. The dispersion<br />

created a loss of community identity as the refugees<br />

assimilated to their various new homes, <strong>and</strong> due to<br />

continued persecution, their faith was effectively<br />

driven underground <strong>for</strong> much of the next century.<br />

This time of underground belief was called the<br />

Time of the Hidden Seed (Groenfeldt 1976:14-15;<br />

Murtagh 1967:4-5).<br />

Members of the <strong>Moravian</strong> Church were <strong>for</strong>ced<br />

to remain dormant into the early 1700s, <strong>and</strong><br />

the geographically fragmented denomination<br />

struggled to continue. In 1722, Count Nicholas von<br />

Zinzendorf of Saxony granted the <strong>Moravian</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

other Protestants sanctuary on his estate, where the<br />

groups collectively built a town called Herrnhut, <strong>and</strong>

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

eventually the towns of Nisky <strong>and</strong> Kleine Welk. The<br />

Count was a Lutheran but became both a benefactor<br />

to <strong>and</strong> a leader of the <strong>Moravian</strong>s. The <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

faith at this point became a “renewed church” <strong>and</strong><br />

is the antecedent of the modern <strong>Moravian</strong> church<br />

(<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> 2007:2; Murtagh 1967:4-5)<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong> denomination from the beginning<br />

of the renewed church was primarily interested in<br />

missionary work, <strong>and</strong> members viewed themselves<br />

not as a distinct denomination but as communal<br />

servants of the Christian faith. Their communistic<br />

mode of living, in which group needs took precedence<br />

over the individual, derived from the many years of<br />

dispersion <strong>and</strong> survival in the face of persecution.<br />

At Herrnhut, two distinct <strong>and</strong> important traditions<br />

were established among the <strong>Moravian</strong>s. The first<br />

was the love feast service, which was a celebratory<br />

event accompanying communion <strong>and</strong> including<br />

consumption of food <strong>and</strong> drink. The second was<br />

the <strong>Moravian</strong> Economy, which was the division of<br />

the congregation into ten living units called choirs.<br />

The Economy was developed in response to the<br />

belief that an individual’s spiritual growth was best<br />

stimulated <strong>and</strong> encouraged by other individuals in<br />

the same life situation. The choirs consisted of: 1.<br />

Married People, 2. Widowers, 3. Widows, 4. Single<br />

Brethren, 5. Single Sisters, 6. Youths, 7. Big Girls, 8.<br />

Little Boys, 9. Little Girls, <strong>and</strong> 10. Infants in Arms.<br />

(Murtagh 1967:5-6; Smaby 1988:9-10).<br />

By the early 1730s, the Herrnhut community was<br />

growing as word of it spread to Bohemia, Moravia,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Silesia. This aroused the suspicions of the local<br />

authorities, who <strong>for</strong>bade further settlement. While<br />

the Lutherans preferred to remain at Herrnhut,<br />

many of the <strong>Moravian</strong>s felt the need to leave. They<br />

wanted to <strong>for</strong>m new colonies in a more hospitable<br />

place where they could follow their faith, receive<br />

additional members, <strong>and</strong> spread the Gospel to<br />

the unchurched. The New World beckoned as a<br />

potential site of such a colony. A group of <strong>Moravian</strong>s<br />

left Germany in 1732 <strong>for</strong> the West Indies, intending<br />

to proselytize <strong>and</strong> spread their faith to the New<br />

World (Groenfeldt 1976:15-16; Levering 1903:30;<br />

Murtagh 1967:6-7).<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong>s of Herrnhut, aware that many<br />

European Protestants had settled in the tolerant<br />

Pennsylvania colony, began to envision per<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

missionary work among the Native Americans <strong>and</strong><br />

unchurched settlers in North America. German<br />

immigration to Pennsylvania began in 1683<br />

when Germantown was founded by Germans<br />

from Krefeld, who came seeking better economic<br />

opportunities. The early eighteenth century saw<br />

the migration of various Protestant factions, also<br />

seeking prosperity <strong>and</strong> freedom of worship, <strong>and</strong><br />

collectively known as the Pennsylvania Dutch. The<br />

group included a diverse array of denominations<br />

which had originated in various European<br />

regions, including Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Palatinate<br />

region of Germany. Two groups of Schwenkfelder<br />

Protestants, harbored by Zinzendorf, migrated to<br />

Pennsylvania in 1733-1734, settling in Germantown<br />

(Murtagh 1967:3-4).<br />

Count von Zinzendorf made arrangements with<br />

leaders of the Georgia colony to create a <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

settlement in Georgia to assist in evangelizing<br />

the Native Americans. Under the direction of<br />

Rev. Augustus Gottlieb Spangenberg, a Lutheran<br />

minister who had joined the <strong>Moravian</strong>s, a small<br />

group of <strong>Moravian</strong> men migrated to Savannah,<br />

Georgia, in 1736 to begin missionary work in the<br />

colony. Although the group had a promising start,<br />

its hopes of a permanent colony in Savannah<br />

were soon dashed by the war between the English<br />

Georgia colony <strong>and</strong> the Spanish Florida colony.<br />

The <strong>Moravian</strong>s’ refusal to bear arms in support of<br />

Georgia soon put them in disfavor with Savannah’s<br />

leaders <strong>and</strong> citizens, <strong>and</strong> the warfare made it<br />

difficult to carry out Native American missionary<br />

work. Over the next four years, the group began to<br />

look elsewhere <strong>for</strong> a place to continue their mission<br />

(Groenfeldt 1976:15-16; Levering 1903:31-40;<br />

Murtagh 1967:6-7).<br />

Beginnings of Bethlehem<br />

Present-day Northampton County, Pennsylvania,<br />

was still wilderness when a 10,000 acre tract was<br />

sold, sometime be<strong>for</strong>e 1737, to William Allen by<br />

Thomas Penn, the son of William Penn. At the time<br />

of the sale, Penn did not yet hold title <strong>and</strong> this l<strong>and</strong><br />

still belonged to the Lenape Indians. In 1686, the<br />

Lenape had made an agreement to grant William<br />

Penn a tract of l<strong>and</strong> between the Delaware River<br />

<strong>and</strong> a line starting at Wrightstown (Bucks County,<br />

running northwest <strong>for</strong> as far as a man could walk<br />

in a day <strong>and</strong> a half. In 1737, Pennsylvania Governor<br />

James Logan decided that solid title to this l<strong>and</strong><br />

should be established, <strong>and</strong> proposed what was<br />

called the Walking Purchase. Following Lenape<br />

custom, a day <strong>and</strong> a half’s walk measured about<br />

30 miles. On September 19, 1737, Logan’s walkers<br />

set out to establish the boundaries. Logan’s ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

to recruit fast walkers <strong>and</strong> clear trails in advance<br />

helped his walkers cover 60 miles in that time,<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 7

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

meaning that the Lenape were <strong>for</strong>ced to relinquish<br />

a much larger tract than they had intended. The<br />

tribe contested the claim but a 1742 meeting of<br />

the Iroquois Confederacy upheld the decision<br />

(Gerhardt et al. 2008:4-5).<br />

William Allen was a Presbyterian of Scots-Irish<br />

descent. Within two years of the Walking Purchase,<br />

other Scots-Irish settlers moved to his l<strong>and</strong> from<br />

New Castle, Delaware, <strong>and</strong> were joined by German<br />

settlers moving north from Bucks County. The<br />

area remained a frontier in its first two decades<br />

(Gerhardt et al. 2008:4-5).<br />

Between 1737 <strong>and</strong> 1740, the <strong>Moravian</strong> colonists of<br />

Savannah ab<strong>and</strong>oned their settlement <strong>and</strong> several<br />

moved to Pennsylvania. Two of their bishops,<br />

Augustus Spangenberg <strong>and</strong> David Nitschmann,<br />

had already traveled there to conduct missionary<br />

work among the Schwenkfelders. English evangelist<br />

George Whitefield hired the <strong>Moravian</strong>s to construct<br />

a school <strong>for</strong> blacks (figure 2-2) at his new settlement<br />

called Nazareth, established in 1740 on 5,000 acres<br />

purchased from William Allen. Nazareth lay in a<br />

near-wilderness, with only a few nearby white<br />

settlements populated by Scots-Irish, <strong>and</strong> Delaware<br />

Indians still had a significant presence. Within a<br />

year, theological differences between Whitefield<br />

<strong>and</strong> the <strong>Moravian</strong>s led the <strong>Moravian</strong>s to seek<br />

their own l<strong>and</strong>. On April 2, 1741, after considering<br />

multiple locations, they purchased property from<br />

William Allen. The 500-acre tract lay ten miles from<br />

Nazareth at the confluence of the Lehigh River<br />

<strong>and</strong> Monocacy Creek, <strong>and</strong> had never been settled.<br />

Just a few months later, Whitefield ab<strong>and</strong>oned his<br />

venture at Nazareth <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Moravian</strong> Church<br />

purchased his entire tract, giving it not one but two<br />

new settlements in Pennsylvania (Murtagh 1967:7,<br />

95-97; Myers 1981:39-41).<br />

Figure 2-2. Nineteenth century view of Whitefield House at<br />

Nazareth, built by <strong>Moravian</strong> settlers in the 1740s (Murtagh<br />

1967:96).<br />

Figure 2-3. 1874 Rufus Grider watercolor showing first log house<br />

in Bethlehem at far left (Murtagh 1967:22).<br />

Bethlehem’s site was chosen <strong>for</strong> its proximity<br />

to a fast-flowing spring at the base of the bluff<br />

overlooking the confluence of creek <strong>and</strong> river.<br />

The town was sited atop the wooded bluff to<br />

avoid floods, meaning that all water used in the<br />

settlement had to be hauled uphill by cart until<br />

the first waterworks was constructed in 1754<br />

(Myers 1981:39-41). The spring of 1741 saw the<br />

planting of the fields <strong>and</strong> construction of the first<br />

log dwelling house there (figure 2-3), which served<br />

initially as both dwelling <strong>and</strong> stable. The small<br />

group of <strong>Moravian</strong> workers began construction<br />

on a much larger log house, the Gemeinhaus, in<br />

September (figure 2-4). Count von Zinzendorf <strong>and</strong><br />

his sixteen-year-old daughter Benigna, along with<br />

Figure 2-4. 1854 Rufus Grider watercolor of the<br />

completed in 1742 (Murtagh 1967:25).<br />

Gemeinhaus,<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 8

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

a small group of companions, arrived <strong>for</strong> a visit<br />

the following winter. On December 24, 1741, the<br />

settlers <strong>and</strong> their guests assembled in the first log<br />

house to celebrate the birth of Christ, <strong>and</strong> named<br />

the settlement Bethlehem (Groenfeldt 1976:16-17;<br />

Levering 1903:40-46, 54, 78-79; <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

2007:2; Myers 1982:13,19-20,39-41).<br />

The first settlers of Bethlehem were initially broken<br />

into two groups: an itinerant congregation whose<br />

sole task was to per<strong>for</strong>m missionary work, <strong>and</strong> a<br />

second home congregation to construct buildings<br />

<strong>and</strong> provide the labor <strong>and</strong> material goods needed to<br />

sustain the entire group (Levering 1903:129-146). A<br />

sawmill, gristmill, <strong>and</strong> small missionary settlement<br />

were built upriver at Gnadenhuetten in 1747. This<br />

sawmill provided much of the wood used to build<br />

the Single Brethren’s House <strong>and</strong> other buildings in<br />

Bethlehem. The wood was sawn <strong>and</strong> then floated<br />

down the Lehigh River. Gnadenhuetten was also<br />

a missionary outpost <strong>and</strong> home to an Native<br />

American congregation of converts (Levering<br />

1903:195-196, 297-321; Smaby 1988:25-26).<br />

Bethlehem: The Eighteenth Century<br />

Bethlehem was initially a communal settlement<br />

restricted to <strong>Moravian</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> was organized under<br />

the <strong>Moravian</strong> Economy established at Herrnhut<br />

(<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> 2007:2). The settlement followed<br />

planning <strong>and</strong> social patterns established at<br />

Herrnhut, which remained the headquarters of the<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> faith. Approval from church leaders at<br />

Herrnhut was required <strong>for</strong> all building plans, giving<br />

Bethlehem untainted European characteristics<br />

from the beginning. The Economy encompassed<br />

not only Bethlehem but the settlement at Nazareth<br />

as well. Individuals worked <strong>for</strong> the good of the<br />

settlement <strong>and</strong> of those they evangelized, <strong>and</strong><br />

received housing, board, <strong>and</strong> basic needs in return<br />

(Murtagh 1967:9-10).<br />

The early buildings housed the home congregation<br />

of church members grouped in the <strong>Moravian</strong> choir<br />

system, as established at Herrnhut. Instead of<br />

nuclear families, church members of all ages were<br />

housed with peers rather than blood relatives.<br />

While married couples <strong>and</strong> infants could remain<br />

together, everyone else from toddlerhood on lived<br />

in choir houses determined by age, sex, <strong>and</strong> marital<br />

status. Each choir shared household responsibilities<br />

<strong>and</strong> common worship. The settlement’s group of<br />

buildings contained the domestic <strong>and</strong> worship<br />

spaces of the community. Building uses were<br />

fluid <strong>and</strong> changed frequently as the community<br />

grew. Initially, the Gemeinhaus housed the different<br />

choirs in sets of rooms or larger dormitories.<br />

As the population grew beyond the available<br />

facilities, the single women’s <strong>and</strong> widows’ choirs<br />

lived in Nazareth due to lack of space to house<br />

them in Bethlehem. Later, multiple large houses<br />

were constructed <strong>for</strong> single men (brothers), single<br />

women (sisters), widows, <strong>and</strong> married couples. The<br />

first buildings were constructed on the north side<br />

of Church Street (originally Sisters’ Lane), east of<br />

what became Main Street (Murtagh 1967:12; Smaby<br />

1988:92-93).<br />

Another important feature of <strong>Moravian</strong> Bethlehem<br />

was the industrial complex that arose to the west of<br />

the central core along the Monocacy Creek (figure<br />

2-5). Here, the community had a waterworks <strong>and</strong><br />

a number of shops <strong>and</strong> structures housing mills,<br />

processing industries, <strong>and</strong> skilled trades. Initially<br />

these structures were log buildings, but between<br />

1759 <strong>and</strong> 1784, most were replaced with permanent<br />

stone structures. A smaller secondary industrial<br />

complex with a sawmill, flax mill, <strong>and</strong> laundry<br />

house was built downstream on the Monocacy<br />

peninsula, southeast of the town (Kane 1963:3-5;<br />

Murtagh 1967:13-15; Myers 1981:35).<br />

On the hillside south of Church Street (originally<br />

called Sisters’ Lane), the <strong>Moravian</strong>s cleared the<br />

trees <strong>and</strong> planted large community gardens to raise<br />

the produce <strong>and</strong> herbs they needed. According to<br />

Figure 2-5. Nineteenth century painting of <strong>Moravian</strong> industrial<br />

complex, with the Single Brethren’s House at rear (Murtagh<br />

1967:91).<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 9

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

contemporary views (figure 2-6), the gardens were<br />

laid out in a <strong>for</strong>mal grid plan. More vegetable plots<br />

lay on S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>, south of the river. The town was<br />

clustered in a tight <strong>for</strong>mation with choir buildings<br />

to the south, the industrial area in the middle,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the farm buildings to the north. Beyond the<br />

farm buildings lay the congregation’s extensive<br />

farml<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> to the east were orchards.<br />

As Bethlehem developed, additional settlers were<br />

moving into the surrounding area. In 1752, the<br />

Pennsylvania Assembly established Northampton<br />

County as the local jurisdiction <strong>and</strong> made Easton<br />

the county seat. Initially Northampton County was<br />

a massive tract, encompassing all of present-day<br />

Northampton, Carbon, Lehigh, Monroe, Pike,<br />

Susquehanna <strong>and</strong> Wayne counties, plus parts of<br />

Brad<strong>for</strong>d, Columbia, Luzerne, Schuylkill, <strong>and</strong><br />

Wyoming counties. Over time additional counties<br />

were subdivided off from Northampton, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

county reached its present size (374 square miles)<br />

in the mid nineteenth century (Gerhardt et al.<br />

2008:5-6).<br />

The French <strong>and</strong> Indian War (1753-1763) was a time<br />

of terror <strong>for</strong> the settlers of Northampton County,<br />

which became the scene of protracted hostilities<br />

between Europeans <strong>and</strong> Native American tribes.<br />

The Lenape, still angry about being cheated by<br />

the Walking Purchase, were part of the uprising.<br />

As the best-established settlement, Bethlehem<br />

became a place of shelter <strong>for</strong> settlers <strong>and</strong> Native<br />

American converts fleeing attacks in more remote<br />

areas. The small <strong>Moravian</strong> mission settlement<br />

at Gnadenhuetten, home to a group of <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

missionaries <strong>and</strong> a congregation of Native American<br />

converts, fell victim to the warfare. On November<br />

24, 1755, Gnadenhuetten was destroyed in a tragic<br />

massacre. Most of the <strong>Moravian</strong> missionaries <strong>and</strong><br />

their congregants were killed <strong>and</strong> their houses <strong>and</strong><br />

mills burned by invading tribes. In the same year,<br />

the provincial government appointed Benjamin<br />

Franklin of Philadelphia to oversee defense ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

on the frontier. Franklin established a chain of<br />

<strong>for</strong>ts between Easton <strong>and</strong> Mercersburg to protect<br />

frontier settlements (Gerhardt et al. 2008:5; Levering<br />

1903:195-196, 297-321; Smaby 1988:31-32).<br />

End of the <strong>Moravian</strong> Economy<br />

1762-1770<br />

Bethlehem remained a communal society from 1745<br />

to 1762, by which time it had become a thriving<br />

settlement. During this time it had also endured<br />

economic hardship, changes in leadership, <strong>and</strong><br />

increasing dissension among its inhabitants. The<br />

focus on missionary work to the exclusion of<br />

good fiscal management, <strong>and</strong> the inability of the<br />

community to sustain itself fully, led Bethlehem<br />

to incur significant debt during the 1750s. As time<br />

went on, many members of the faith were beginning<br />

to oppose the Economy system as a viable social<br />

institution. Few of the other <strong>Moravian</strong> settlements in<br />

America adhered to the Economy, <strong>and</strong> Bethlehem’s<br />

leaders eventually saw dissolution of the Economy<br />

as the best chance of repaying the community’s<br />

debt. After the death of Count von Zinzendorf in<br />

1760, it became clear that the community’s previous<br />

emphasis on missionary work would have to be<br />

pushed aside in favor of gaining economic viability.<br />

Leaders were also concerned that the dissension<br />

was eroding the faith <strong>and</strong> cooperative spirit of<br />

community members (Hamilton 1988:4-5; <strong>Moravian</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong> 2007:2-4; Myers 1982:35-36; Smaby 1988:26-<br />

32).<br />

In 1761, it was decided that the communal Economy<br />

would be ab<strong>and</strong>oned in favor of nuclear households.<br />

This change was implemented beginning in early<br />

1762. Instead of living in choirs, married couples<br />

would now have their own households, kinship<br />

ties would take precedence over being with one’s<br />

peers, <strong>and</strong> children would be raised by their<br />

own parents rather than being sent to communal<br />

housing at 18 months. Initially the farms, industries<br />

<strong>and</strong> mills were still operated by the community, but<br />

eventually these occupations were privatized. Only<br />

single people <strong>and</strong> widows remained with their<br />

choirs, but they now were given wages <strong>for</strong> their<br />

work <strong>and</strong> paid nominal rent <strong>for</strong> their housing <strong>and</strong><br />

food. Bethlehem transitioned from a communal<br />

society to a church-village. The church maintained<br />

tight controls on commerce <strong>and</strong> pay rates <strong>and</strong><br />

restricted purchases from outside the community. A<br />

lease system was established <strong>for</strong> the property in the<br />

town, where residents owned their buildings but<br />

leased their l<strong>and</strong> from the church. Approval was<br />

needed to rent or sell buildings, <strong>and</strong> the selection<br />

of appropriate tenants was tightly controlled by the<br />

village authorities (Levering 1903:650-651; Smaby<br />

1988:32-36).<br />

The community was immediately faced with the<br />

need to house 50 married couples <strong>and</strong> their families<br />

in individual quarters. Buildings with interiors<br />

designed <strong>for</strong> communal living had to be redesigned<br />

to accommodate individual households, <strong>and</strong><br />

smaller new houses began to spread northward<br />

from the community core. Older buildings with<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 10

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

attached apartments, such as mills <strong>and</strong> industry<br />

buildings, were used as well. The provision of<br />

individual kitchens <strong>and</strong> storage areas <strong>for</strong> each<br />

new household was a particular problem, since<br />

communal Bethlehem had perhaps six or seven<br />

large kitchens (Smaby 1988:107).<br />

Figure 2-6. Detail, 1757 view of Bethlehem by Nicholas Garrison.<br />

Note garden plots below the Single Brethren’s House (<strong>Moravian</strong><br />

Church Archives).<br />

The l<strong>and</strong>scape of the town also adapted somewhat<br />

to accommodate these changes. The farm buildings<br />

were moved northward to accommodate the<br />

construction of new individual houses. Community<br />

gardens became less important as individual<br />

households <strong>for</strong>med. By 1766, the large gardens of<br />

previous years were still present, but a new group<br />

of gardens had <strong>for</strong>med on S<strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong> southwest of<br />

the town. These produce gardens replaced an earlier<br />

large garden area (see figure 2-6). They were laid<br />

out in small oblong plots flanking a straight center<br />

path, <strong>and</strong> were designated as “citizens’ gardens” in<br />

a 1766 city plan (figures 2-7 <strong>and</strong> 2-8). This plan also<br />

shows small rectangular grid-plan gardens behind<br />

the store <strong>and</strong> several of the homes on the Ladengasse<br />

(Murtagh 1967:13-15).<br />

The Buildings of Early Bethlehem<br />

1742-1770<br />

Figure 2-7. 1766 plan of Bethlehem (Murtagh 1967:15).<br />

Figure 2-8. View of Bethlehem in 1754 (<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> Public<br />

Relations).<br />

Bethlehem’s first house was a simple log structure<br />

(see figure 2-3), measuring twenty by <strong>for</strong>ty feet,<br />

<strong>and</strong> housing settlers in one section <strong>and</strong> livestock<br />

in the other. The first Bethlehem settlers resided at<br />

Nazareth or at the home of a friend south of the river<br />

until the house was habitable. As the first building<br />

in the settlement, the log house also functioned<br />

as the community’s worship space during the<br />

first year, as farming <strong>and</strong> building work went on<br />

around it. The group cleared fields <strong>and</strong> planted<br />

crops, completing a successful harvest in the fall of<br />

1741 <strong>and</strong> storing their grain in the log house. This<br />

house no longer st<strong>and</strong>s. In 1823, it was demolished<br />

to build a livery stable <strong>for</strong> a new tavern, which is<br />

now the Eagle Hotel (Levering 1903:61-62, 633-634;<br />

Myers 1981:19-22).<br />

The earliest building extant in Bethlehem is the<br />

Gemeinhaus, a massive log building which was<br />

built by the <strong>Moravian</strong> settlers during late 1741<br />

<strong>and</strong> completed in the spring of 1742 (see figure<br />

2-4). Almost immediately, it was enlarged with an<br />

addition at the east end, completed in August 1743.<br />

After the addition, the finished building contained<br />

two dormitories, twelve rooms, <strong>and</strong> a second-floor<br />

chapel <strong>for</strong> worship. Although other buildings<br />

soon followed, the Gemeinhaus was the core of the<br />

settlement <strong>and</strong> continued to house community<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 11

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

leaders even after larger new buildings had been<br />

constructed (Hamilton 1988:9-10).<br />

A new stone Choir House <strong>for</strong> the single brothers<br />

was erected during the second half of 1744. The<br />

single brethren used the house as both a residence<br />

<strong>and</strong> as workshop space <strong>for</strong> several industries, such<br />

as weaving <strong>and</strong> hatmaking. The initial population<br />

of 50 men <strong>and</strong> several boys grew rapidly to the<br />

point where they needed a larger house. In 1748,<br />

a new Single Brethren’s House was completed<br />

across the street. The single women <strong>and</strong> girls of the<br />

congregation, who had been residing in Nazareth<br />

since 1745 due to space constraints in Bethlehem,<br />

took possession of the older house, which became<br />

known as the Sisters’ House. This building was<br />

extended in 1752 with a perpendicular annex<br />

connecting the Sisters’ House to the Bell House.<br />

Due to unstable ground caused by a failure in the<br />

limestone base <strong>and</strong> subsoil under the house, the<br />

wing was supported by new buttresses, <strong>and</strong> its<br />

heavy roof tiles were removed in 1755 <strong>and</strong> replaced<br />

with wood shingles to lighten the roof load <strong>and</strong><br />

stabilize the building. Another extension was<br />

made at the east end in 1773 (Hamilton 1988:11-12;<br />

Murtagh 1967:39).<br />

completed <strong>and</strong> dedicated on November 16, 1748.<br />

On that evening, a celebratory procession of men<br />

was made from the old house to the new one, <strong>and</strong><br />

a love feast was held in the new building’s chapel,<br />

after which the 72 residents spent their first night<br />

in the new dormitories. Large though it was, the<br />

Single Brethren’s House was soon outgrown, <strong>and</strong><br />

new wings were added in 1762 <strong>and</strong> 1768. Its roof<br />

was used <strong>for</strong> celebratory music per<strong>for</strong>mances <strong>and</strong><br />

to broadcast important messages, such as deaths<br />

of congregation members, to the community<br />

(Hamilton 1788:15-16; <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> 2007:5).<br />

The growing <strong>Moravian</strong> population soon exceeded<br />

the capacity of the Gemeinhaus chapel, <strong>and</strong> a new<br />

perpendicular chapel was constructed in 1751<br />

between the Bell House <strong>and</strong> the Gemeinhaus. The<br />

first floor contained a dining hall <strong>for</strong> the Married<br />

People’s Choir <strong>and</strong> the chapel was on the second<br />

floor. As with the Sisters’ House, the ground beneath<br />

the Chapel soon appeared to be faulty <strong>and</strong> the<br />

building was stabilized by constructing buttresses<br />

on the outer wall <strong>and</strong> replacing the heavy tile roof<br />

with shingles.<br />

East of the Gemeinhaus, a new square stone building<br />

was constructed in 1745-1746 as additional space<br />

<strong>for</strong> the single brethren’s kitchen <strong>and</strong> a kitchen,<br />

dining room, <strong>and</strong> upstairs quarters <strong>for</strong> the married<br />

people’s choir. Within three years, the building was<br />

extended at both ends. A bell tower atop the central<br />

section gave the building its name: the Bell House<br />

(figure 2-9). The bell was rung daily to signal rising,<br />

meals, the end of work hours, <strong>and</strong> worship services<br />

(Hamilton 1988:13-14).<br />

The new Single Brethren’s House of 1748 (figure<br />

2-10) was a massive stone building, four stories<br />

plus attic <strong>and</strong> basement, <strong>and</strong> featured a large<br />

plat<strong>for</strong>m atop its roof. Its plan was derived from<br />

a building in Herrnhut, Germany. The size of the<br />

building was dictated by the disproportionately<br />

large population of single male settlers <strong>and</strong> the<br />

various trades they intended to pursue within<br />

their choir house. The Single Brethren’s House<br />

was constructed with lumber floated downstream<br />

from the Gnadenhuetten sawmill on the Lehigh<br />

River. Four stonemasons from outside Bethlehem<br />

oversaw the construction, <strong>and</strong> labor was provided<br />

by men from Bethlehem. The building site was<br />

selected <strong>and</strong> staked off on January 10, 1748,<br />

with construction beginning at that time. The<br />

cornerstone was laid April 7, <strong>and</strong> the building was<br />

Figure 2-9. Undated nineteenth-century view of Bell House with<br />

Sisters’ House at right (<strong>Moravian</strong> Church Archives).<br />

Figure 2-10. Single Brethren’s House (1748), shown at center of<br />

1754 engraving (Murtagh 1967:57).<br />

John Milner Associates • October 2009 • Chapter 2 • Historic Overview • 12

<strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> • <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

The last major building of the eighteenth century<br />

was the Widows’ House (figure 2-11), erected<br />

in 1766-1768 to house the growing number of<br />

widows in the community. Although a need <strong>for</strong><br />

such a building had been apparent as early as 1759,<br />

other projects took priority <strong>and</strong> the widows of the<br />

community continued to reside in Nazareth until<br />

the project was finally completed. The site chosen<br />

was <strong>for</strong>merly part of the congregational garden<br />

<strong>and</strong> eleven widows were the first occupants. The<br />

Widows’ House appears to have attracted several<br />

distinguished visitors, including both Martha <strong>and</strong><br />

George Washington. The east end of the building<br />

was extended 20 feet in 1794-1795 (Hamilton<br />

1988:23-25; <strong>Moravian</strong> <strong>College</strong> 2007:18).<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> Bethlehem from the beginning was a<br />

novelty in America. Much as the Amish attract<br />

tourists today, eighteenth- <strong>and</strong> early nineteenthcentury<br />

Bethlehem drew a number of visitors<br />

fascinated by the <strong>Moravian</strong>s’ unique communal<br />

lifestyle, educational system, <strong>and</strong> technological<br />

achievements such as the waterworks. The<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong>s welcomed their visitors but were<br />

concerned about too much contact with outsiders,<br />

<strong>and</strong> guests were not permitted to roam freely<br />

without an escort. Within a short time, the <strong>Moravian</strong>s<br />

felt compelled to construct inns to house visitors in<br />

a more hospitable manner, <strong>and</strong> at the same time<br />

prevent too much interference with their routine<br />

(Smaby 1988:97-99).<br />

Two inns were constructed to serve the travelers.<br />

The Crown Inn, located in the farml<strong>and</strong> south of<br />

the Lehigh River, was constructed in 1745. A nearby<br />

ferry transported visitors across the river to the<br />

<strong>Moravian</strong> settlement. The ferry system was unwieldy<br />

<strong>and</strong> community leaders agitated <strong>for</strong> many years to<br />

build a bridge across the river. Stagecoach service<br />

was intermittent until after the Revolution. The<br />

creation of the national post road system brought<br />

regular stagecoach service to Bethlehem in 1785,<br />

exacerbating the need <strong>for</strong> a more efficient means<br />

of ingress. In 1794, the first Lehigh River bridge<br />

was completed <strong>and</strong> authorized by the state as a toll<br />

bridge. The ferry system was ab<strong>and</strong>oned <strong>and</strong> the<br />

now-unnecessary Crown Inn became a farmhouse<br />

(Levering 1903:544-547; Smaby 1988:99).<br />

A “congregational inn,” later known as the Sun Inn,<br />

was constructed ca. 1758-1760 near the west end of<br />

Church Street. It was a large limestone building with<br />

a clay-tiled Germanic jerkinhead roofline. With its<br />

inn complete, Bethlehem welcomed many famous<br />

figures of the era, including Martha Washington in<br />