St. Mary's College of Maryland Preservation Master Plan

St. Mary's College of Maryland Preservation Master Plan

St. Mary's College of Maryland Preservation Master Plan

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

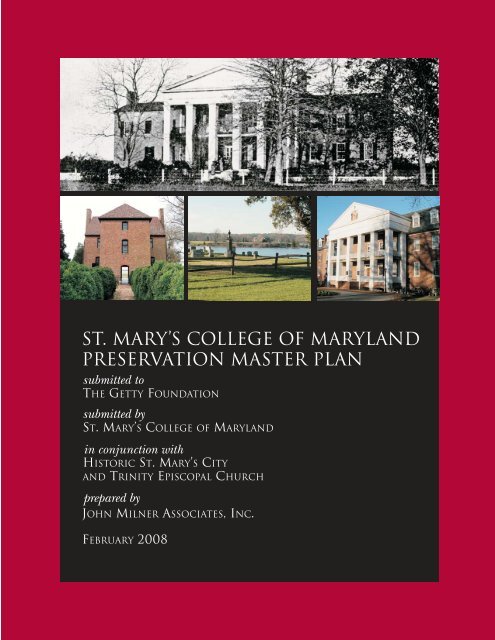

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>submitted toTHE GETTY FOUNDATIONsubmitted byST. MARY’S COLLEGE OF MARYLANDin conjunction withHISTORIC ST. MARY’S CITYAND TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCHprepared byJOHN MILNER ASSOCIATES, INC.FEBRUARY 2008

<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>for<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>in conjunction withHistoric <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s CityandTrinity Episcopal ChurchPrepared By:JOHN MILNER ASSOCIATES, INC.West Chester, PennsylvaniaKimberly BaptisteLori AumentLaura Knott, ASLAKatherine L. FarnhamDonna SeifertDawn ThomasFebruary 2008

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008AcknowledgementsThe funding for the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> was provided through a generousgrant available from:The Getty FoundationCampus Heritage Grant ProgramLos Angeles, CaliforniaThroughout the planning process John Milner Associates, Inc. was supported by members <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> <strong>St</strong>eering Committee who gave generously <strong>of</strong> their time and expertise. Thesteering committee represented <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, and TrinityEpiscopal Church.Katherine B. Meatyard, Project Director, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>The Rev. John Ball, Rector, Trinity Episcopal ChurchChip Jackson, Facilities Manager, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Julie King, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Anthropology, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Joan Poor, Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Economics, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Joe <strong>St</strong>orey, Trinity Episcopal ChurchMartin Sullivan, Director, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s CityLynn Williamson, Trinity Episcopal ChurchSpecial thanks and acknowledgement are also extended to the following individuals who providedinvaluable assistance, insights, and knowledge throughout the duration <strong>of</strong> the planning process:Anne Grulich, Assistant to Katherine Meatyard, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Larry Hartwick, Capital Project Manager, Office <strong>of</strong> Facilities, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Janet Haugaard, Executive Editor and Writer, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Michelle Marsich, <strong>St</strong>udent Assistant, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Carol Moody, Archivist, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s CityEd Morasch, Office <strong>of</strong> Facilities, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Lynda Purdy, Secretary, Trinity Episcopal ChurchFrancis Raley, Office <strong>of</strong> Facilities, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Kat Ryner, Archivist, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>Derek Thornton, Office <strong>of</strong> Facilities, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Table <strong>of</strong> ContentsST. MARY’S COLLEGE OF MARYLANDPRESERVATION MASTER PLANExecutive SummaryChapter 1: Background and Purpose ............................................................................1-1OVERVIEW <strong>of</strong> the plan .................................................................................................. 1-1The <strong>College</strong>, The City, and The Church ............................................................................ 1-2The <strong>St</strong>udy Area ................................................................................................................. 1-4How the <strong>Plan</strong> is Organized ................................................................................................ 1.5preservation CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 1-9The Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Interior’s <strong>St</strong>andards ......................................................................... 1-9<strong>Preservation</strong> Treatments ................................................................................................. 1-14Chapter 2: History <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong> ...................................................2-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 2-1HISTORIC PERIODS ............................................................................................................ 2-1Early Colonial Settlement .................................................................................................. 2-1The Growth <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City ........................................................................................... 2-5The Founding <strong>of</strong> Trinity Church ......................................................................................... 2-8<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Female Seminary ........................................................................................... 2-16Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City .................................................................................................... 2-33The Tercentenary Commission ........................................................................................ 2-35The Replica <strong>St</strong>ate House ................................................................................................ 2-36Suburbanization and <strong>Preservation</strong> .................................................................................. 2-37Chapter 3: Relevant Historic Contexts ..........................................................................3-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3-1HISTORIC THEMES ............................................................................................................. 3-1Classicism and <strong>College</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning: 1820-1860 ................................................................... 3-1Mythmaking and Commemoration: 1820-1861 ................................................................. 3-4Romanticism and Design: 1850-1890 ............................................................................... 3-6Colonial Revival Design: 1890-1965 ................................................................................. 3-7<strong>St</strong>atement <strong>of</strong> Campus Significance ................................................................................... 3-8

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Chapter 4: <strong>Plan</strong>ning, Interpretation, and Management .................................................4-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 4-1PLANNING IN THE HISTORIC SECTOR ............................................................................. 4-1Past <strong>Plan</strong>ning Documents ................................................................................................. 4-1Current and Future <strong>Plan</strong>ning ............................................................................................. 4-4MANAGEMENT AND MAINTENANCE ................................................................................. 4-7Facilities and Maintenance <strong>St</strong>aff ....................................................................................... 4-8Policies and Procedures ................................................................................................... 4-8General Maintenance Recommendations ......................................................................... 4-9Management Recommendations .................................................................................... 4-10PROGRAMMING AND INTERPRETATION .........................................................................4-11Interpreting History ...........................................................................................................4-11Programming and Interpretive Recommendations .......................................................... 4-12Chapter 5: Existing Conditions - Cultural Landscapes ..................................................5-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5-1Landscape Context ........................................................................................................... 5-1Landscape Methodology ................................................................................................... 5-3Archeological Methodology ............................................................................................... 5-4Precincts and Character Areas ......................................................................................... 5-5LANDSCAPE CONDITIONS AND ASSESSMENTS ............................................................. 5-7<strong>College</strong> Precinct ................................................................................................................ 5-9Trinity Precinct ................................................................................................................. 5-29<strong>St</strong>ate House Precinct ...................................................................................................... 5-39Riparian Precinct ............................................................................................................. 5-51Chapter 6: Landscape Treatment Guidelines ...............................................................6-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 6-1Chapter Overview ............................................................................................................. 6-1<strong>Preservation</strong> Goals and Issues ......................................................................................... 6-2LANDSCAPE TREATMENT GUIDELINES ........................................................................... 6-6General Guidelines ........................................................................................................... 6-6Spatial Organization .......................................................................................................... 6-7Land Use ........................................................................................................................... 6-8Topography ....................................................................................................................... 6-8Circulation ......................................................................................................................... 6-8Vegetation ....................................................................................................................... 6-10Buildings and <strong>St</strong>ructures ..................................................................................................6-11Views and Vistas ............................................................................................................. 6-12Small-scale Features ...................................................................................................... 6-12Monuments and Memorials ............................................................................................. 6-13Archeology ...................................................................................................................... 6-15New Construction ............................................................................................................ 6-15Accessibility ..................................................................................................................... 6-16

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Health and Safety ............................................................................................................ 6-16Environment .................................................................................................................... 6-16Energy Efficiency ............................................................................................................ 6-16Chapter 7: Landscape Treatment Recommendations ..................................................7-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 7-1SPECIFIC TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................. 7-2<strong>College</strong> Precinct ................................................................................................................ 7-2Trinity Precinct ................................................................................................................... 7-9<strong>St</strong>ate House Precinct ...................................................................................................... 7-13Riparian Precinct ............................................................................................................. 7-17Chapter 8: Existing Conditions - Historic Buildings .......................................................8-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 8-1Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 8-1HISTORIC DISTRICTS ......................................................................................................... 8-3Calvert Hall ........................................................................................................................ 8-5<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Hall ................................................................................................................. 8-18Trinity Church .................................................................................................................. 8-26<strong>St</strong>ate House .................................................................................................................... 8-36OTHER BUILDINGS IN HISTORIC QUADRANT ............................................................... 8-42Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 8-42Methodology .................................................................................................................... 8-42Other Historic Buildings ................................................................................................... 8-44Chapter 9: Architectural Treatment Guidelines .............................................................9-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 9-1Applying Historic <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>St</strong>andards ......................................................................... 9-1Architectural Overview ...................................................................................................... 9-2ARCHITECTURAL TREATMENT GUIDELINES ................................................................... 9-4Site Drainage .................................................................................................................... 9-4Concrete ............................................................................................................................ 9-7Masonry ...........................................................................................................................9-11Metals .............................................................................................................................. 9-30Exterior and <strong>St</strong>ructural Woodwork ................................................................................... 9-32Ro<strong>of</strong>s and Drainage Systems ......................................................................................... 9-41Doors ............................................................................................................................... 9-51Windows .......................................................................................................................... 9-54<strong>St</strong>ucco ............................................................................................................................. 9-61Paint ................................................................................................................................ 9-64Interiors ........................................................................................................................... 9-69

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Chapter 10: Building-Specific <strong>Preservation</strong> Recommendations .................................10-1INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 10-1Recommendation Format ................................................................................................ 10-1Special Provisions for Historic Buildings ......................................................................... 10-2CALVERT HALL .................................................................................................................. 10-5Level 1: Life Safety and Deteriorated Elements .............................................................. 10-5Level 2: Required Work ................................................................................................... 10-6Level 3: Maintenance Level Work ................................................................................... 10-9New Work ...................................................................................................................... 10-10ST. MARY’S HALL ..............................................................................................................10-11Level 1: Life Safety and Deteriorated Elements .............................................................10-11Level 2: Required Work ................................................................................................. 10-12Level 3: Maintenance Level Work ................................................................................. 10-14New Work ...................................................................................................................... 10-15TRINITY CHURCH ............................................................................................................ 10-16Level 1: Life Safety and Deteriorated Elements ............................................................ 10-16Level 2: Required Work ................................................................................................. 10-16Level 3: Maintenance Level Work ................................................................................. 10-18New Work ...................................................................................................................... 10-18STATE HOUSE ................................................................................................................. 10-20Level 1: Life Safety and Deteriorated Elements ............................................................ 10-20Level 2: Required Work ................................................................................................. 10-20Level 3: Maintenance Level Work ................................................................................. 10-21New Work ...................................................................................................................... 10-22Chapter 11: Guidelines for New Construction Projects ...............................................11-1INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................11-1OTHER CONSTRUCTION GUIDELINES ............................................................................11-1Exterior Addition and Adaptive Reuse Projects ................................................................11-1New Buildings and Construction ......................................................................................11-4Barrier-Free Access .........................................................................................................11-6Sustainable Design Opportunities ....................................................................................11-7Works Cited .................................................................................................................12-1AppendicesAPPENDIX A: HISTORIC LANDSCAPE TIMELINE

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Executive Summary<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, and TrinityChurch cumulatively have a long and interwoven history that isdeeply rooted in the origins <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>. Located on a neck <strong>of</strong>land that extends into the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s River, these three institutionsstand on adjacent properties and share three centuries <strong>of</strong> history.Before the college and church were formed, the land on whichthey stand was a part <strong>of</strong> the site <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>’s first capital city.As a liberal arts college, the location <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> on asite that is connected to the principles <strong>of</strong> religious toleration andfreedom from ignorance and prejudice is particularly meaningful.Today, much <strong>of</strong> the historic sector <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Maryland</strong> campus is listed as a National Register Historic Districtdue to the large quantity <strong>of</strong> archeological remains dating back tothe seventeenth century.In 2006 the <strong>College</strong> was awarded a Campus Heritage Grant byThe Getty Foundation to develop a <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> toaddress preservation issues and building concerns for two collegebuildings – Calvert and <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Halls, as well as two neighboringbuildings, the 1934 <strong>St</strong>ate House which is owned by Historic <strong>St</strong>.Mary’s City, and the nineteenth century Trinity Episcopal Church.Due to the sensitive archeological resources associated with thesesites, archeological research and landscape documentation andrecommendations were identified as key aspects <strong>of</strong> the planningprocess. The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is to provide a tool to thevarious entities regarding how to better care for and maintain theirhistoric resources into the future.In the Summer <strong>of</strong> 2006, John Milner Associates, Inc. (JMA) wasselected by the <strong>College</strong> and its project partners to prepare a<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> that was considerate <strong>of</strong> and sympatheticto the needs and objectives <strong>of</strong> the <strong>College</strong>, City, and Church. The<strong>Plan</strong> is intended to help each entity manage change and protectextant resources, and to foster ongoing relationships between eachinstitution so they can continue to work together cooperatively topreserve their shared histories. Together, the institutions can pooltheir resources to tell the story <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong> and the significance<strong>of</strong> their special place in that history.The overall plan for the institutions is broken down into three primarysections: <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>, Landscape Management <strong>Plan</strong>,and Historic Building Management <strong>Plan</strong>. The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong><strong>Plan</strong> provides the framework and basis for subsequent sectionsand includes discussions on general administrative topics, suchas planning, programming, interpretation, and management. AHistorical Overview which describes the history and significance<strong>of</strong> the study area and each institution is also included. TheLandscape Management <strong>Plan</strong> looks at existing conditions <strong>of</strong>

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008landscape features within the study area and provides generalguidelines and recommendations for caring for and maintainingthose features into the future.The Historic Building Management <strong>Plan</strong> looks closely at thefour primary historic buildings within the designated study area:Calvert and <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Halls, the <strong>St</strong>ate House, and Trinity Church.Each was carefully studied to identify issues and recommendedprojects. General treatment guidelines and recommendationswere developed that could be applied to any historic buildingowned by each entity to ensure proper maintenance and upkeep<strong>of</strong> the historic fabric.The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> should play a direct role in futureplanning and development efforts for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Maryland</strong>, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, and Trinity Church. The <strong>Plan</strong>will be used as an informational tool by decision-makers as optionsare presented for building modifications and new constructionprojects on the site <strong>of</strong> Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City. Properly caring for,preserving, and enhancing the irreplaceable resources <strong>of</strong> the siteis the overarching guiding principle for the development <strong>of</strong> this<strong>Plan</strong> and is reinforced throughout the document with thoughtfuland sensitive recommendations for preservation into the future.The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is intended to supplement othercampus planning initiatives that have been undertaken by the<strong>College</strong> in collaboration with Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City and TrinityChurch. The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is the natural next step forthe entities to come together and can be seen as a component <strong>of</strong>the development <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Maryland</strong> Heritage Project in 2000. Thisjoint program, like the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> process, ensuresthat the <strong>College</strong>, City, and Church will have the opportunity towork together to advance scholarship, study, and interpretation inthe historic sector <strong>of</strong> the campus. While other campus planninginitiatives focus on growth and expansion, the <strong>Preservation</strong><strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> provides recommendations for how to accommodatethat growth in a sensitive and sympathetic manner within thehistoric sector. While the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> does notdiscourage change and evolution, understanding that change isto be expected over time, it does provide the guidance to ensurethat change is accommodated in a manner that is consistent withthe historical significance <strong>of</strong> the study area.

PRESERVATION MASTER PLAN

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Chapter 1:Background and PurposeOVERVIEW <strong>of</strong> the plan<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong> is a four-year liberal artscollege which was founded in 1840. The college campuslies along the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s River, partially occupying the site <strong>of</strong><strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, <strong>Maryland</strong>’s 17 th century capital.In 2006, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> applied for and receivedfunding from The Getty Foundation’s Campus HeritageGrant Program to develop a <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> for aspecified study area within the historic sector <strong>of</strong> the <strong>College</strong>which includes lands owned by the <strong>College</strong>, Historic <strong>St</strong>.Mary’s City, and Trinity Episcopal Church. The need forsuch a plan was in response to the <strong>College</strong>’s recognition <strong>of</strong>the fragility <strong>of</strong> its historic campus and surrounding lands andnatural features.The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> will assist <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong>and its project partners – Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City and TrinityChurch - in addressing existing planning gaps as theyrelate to historic resources and improving stewardship<strong>of</strong> the existing resources. The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>provides the involved entities with a means to augmentand complement the 2006 Campus <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> which hasrecommended changes within the historic sector <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>.Mary’s campus.The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong>looks holistically at the campus and adjacent lands withinthe study area. Using the past as a framework, the planprovides guidance for stewardship and decision-makingas it relates to preserving, protecting, understanding, andinterpreting the collective stories <strong>of</strong> the past and resourcesassociated with them. The heart <strong>of</strong> the plan can be foundin the recommendations and guidelines sections whichprovide the tools and solutions necessary to effectively makedecisions pertaining to historic resources. The guidelinesare intended to inspire creative and thoughtful solutions asproblems or issues arise.Page 1-1

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008The <strong>College</strong>, The City, and The Church<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, andTrinity Church are three unique entities that share a past,present, and future. With historic resources that lie adjacentto one another within the historic sector <strong>of</strong> the campus,the <strong>College</strong>, City, and Church physically and functionallyhave a long-standing relationship. The entities have joinedtogether to define a vision for the future <strong>of</strong> the historicsector with respect to land use, development, and facilityimprovements.Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City is an AAM-accredited museum <strong>of</strong>history and archeology that is legislatively affiliated with the<strong>College</strong> in an effort to preserve and protect the NationalHistoric Landmark District. The 850-acre commemorativelandscape has been the site <strong>of</strong> historical and archeologicalresearch and study for more than thirty years. The City isgenerally regarded as one <strong>of</strong> the country’s best preservedarcheological laboratories.Trinity Church was consecrated in 1829 and has served thespiritual needs <strong>of</strong> the local community at this location sincethe 17 th century.The <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is another step in the processto foster cooperation and arrive at a joint consensusregarding the appropriate future for the study area. Together,the three entities have determined that a plan is neededto augment their other planning efforts which focuses onaddressing issues associated with cultural landscaperesources and historic buildings. The <strong>College</strong>, City, andChurch have selected four buildings and their adjacentlandscapes to serve as the focus <strong>of</strong> this planning effort. Theselected buildings represent the oldest and most historicallysignificant buildings and landscapes within the historicsector:Page 1-2• Calvert Hall (1924) replaced the original 1845 buildingwhich was destroyed by a fire and was the first structureto be built in association with the establishment <strong>of</strong> the<strong>College</strong>.• <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Hall (1906) was the original Music Hall andis still used as auditorium space. It is the oldest original<strong>College</strong> building.• <strong>St</strong>ate House (1934) is a reconstruction <strong>of</strong> the original<strong>St</strong>ate House and was built to commemorate the 300 thanniversary <strong>of</strong> the settlement <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>’s first capital.• Trinity Church (1829) was built to replace an existingchapel and was consecrated as a chapel <strong>of</strong> ease for <strong>St</strong>.Mary’s Episcopal Parish in 1831

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> Historic Sector <strong>St</strong>udy Area,boundaries outlined at lower left.

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008The <strong>St</strong>udy AreaThe study area addressed within the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong><strong>Plan</strong> is partially located within the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City NationalHistoric Landmark District and includes properties ownedby the <strong>College</strong>, Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, and TrinityChurch. The Landmark District serves as an archeologicalcommemoration <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>’s colonial-period history, butdoes not include the standing structures belonging to thethree institutions.The preservation plan’s study area, which includes Calvertand <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Hall, the <strong>St</strong>ate House, and Trinity Church,lies within the boundaries <strong>of</strong> what is known, for planningpurposes, as the historic sector <strong>of</strong> campus. The historicsector contains academic, administrative, residential, andrecreational facilities associated with the college, as well asthe Church and related support buildings, the <strong>St</strong>ate Houseand the Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City Post Office. The historicsector is roughly triangular in shape and lies between Rt. 5and the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s River. Old Brome’s Wharf Rd. and Old<strong>St</strong>ate Rd. intersect at its center.The <strong>Plan</strong>ning ProcessThe <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> was developed througha collaborative effort between the <strong>St</strong>eering Committee,including representatives <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>,Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, and Trinity Episcopal Church,and the outside preservation planning consultant JMA.The JMA project team met with the <strong>St</strong>eering Committeebefore initiating fieldwork and background research t<strong>of</strong>orm establish the boundaries <strong>of</strong> the study area, whichwas restricted to the historic sector. Team memberscarefully studied past documentation on the sites andassessed the existing conditions <strong>of</strong> the landscape and thebuilt environment, including the status <strong>of</strong> archeologicalinvestigations within the historic sector. Backgroundresearch helped to assess the overall historic significance<strong>of</strong> various resources. Based upon fieldwork and evaluation<strong>of</strong> existing conditions, recommendations for the futuremanagement <strong>of</strong> the landscape and the built environmentwere formulated and presented. Periodic presentationsand draft report submissions were reviewed by the <strong>St</strong>eeringCommittee. Their comments and concerns are reflected inthe final <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>.Page 1-4

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008How the <strong>Plan</strong> is OrganizedThe planning process for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>resulted in a planning document that is divided into threeprimary sections: 1) <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>St</strong>rategies;2) Landscape Management <strong>Plan</strong>; 3) Historic BuildingManagement <strong>Plan</strong>. Together, the three sections comprisethe <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Maryland</strong>.<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>St</strong>rategies includes the overviewsections <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>, as well asrecommendations and guidelines for planning, management,and administration as they generally relate to historicresources within the study area. <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning<strong>St</strong>rategies includes five chapters:• Background and Purpose• History <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s• Historic Contexts for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s• Programming, Interpretation, and <strong>Plan</strong>ning• Management and AdministrationThe Landscape Management <strong>Plan</strong> consists <strong>of</strong> three chaptersthat focus on the cultural landscapes associated with thedesignated study area. The chapters included within thissection are:• Existing Conditions: Cultural Landscapes• Landscape Treatment Guidelines• RecommendationsResourcesfor Cultural LandscapeThe Historic Building Management <strong>Plan</strong> covers specifictopics related to historic buildings in, and around, the studyarea. The chapters included within the Historic BuildingManagement <strong>Plan</strong> are:• Existing Conditions: Historic Buildings• Architectural Treatment Guidelines• Building Specific Recommendations• Guidelines for New ConstructionSpecific information and topics included within each chapteris included below to serve as a reference regarding theorganization and contents <strong>of</strong> the full <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong><strong>Plan</strong> document:Page 1-5

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Chapter 1: Background and PurposeChapter 1 discusses the background which led up to theplanning process and why it is important and meaningful tothe three entities involved: <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>,Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City, and Trinity Episcopal Church.Previous planning and preservation efforts and an overview<strong>of</strong> the preservation context and approach are included withinthis chapter. Chapter 1 is intended to lay the frameworkfor the significance <strong>of</strong> the plan, the goals <strong>of</strong> the planningprocess, and how the plan can be used to enhance theresources within the study area.Chapter 2: History <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’sChapter 2 explores the rich history <strong>of</strong> the <strong>College</strong>, the City,and the Church, identifying significant events associated withtheir development and how their histories are intertwined.The history is divided into significant periods and provides abasis for understanding the significance <strong>of</strong> the buildings andlandscapes covered in the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>.Chapter 3: Historic Contexts for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’sHistoric contexts provide a framework for understanding thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> the study area as it relates to events andtrends that were occurring on regional and national levelsand how they influenced and impacted planning, design,and development within the study area.Chapter 4: <strong>Plan</strong>ning, Interpretation, and ManagementThe rich history <strong>of</strong> the study area is an important asset andresource that should be preserved and protected for futuregenerations to enjoy and learn from. This chapter includesgeneral recommendations and ideas for telling the story<strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s. General planning recommendations whichlook at the general viability and needs <strong>of</strong> the <strong>College</strong> andsurrounding entities are also discussed in Chapter 4. Currentreview and decision-making procedures for the <strong>College</strong>,City, and Church, as well as the relationship between each<strong>of</strong> the entities as it relates to collaboration and joint decisionmakingfor projects impacting historic buildings, landscapes,and resources, is summarized.Page 1-6Chapter 5: Existing Conditions: Cultural LandscapesChapter 5 includes an inventory and assessment <strong>of</strong> thecultural landscape resources within the defined studyarea. In order to get a better understanding <strong>of</strong> the differentlandscape characteristics, the study area was brokendown into four character areas with similar attributes, andspecific landscape elements are discussed for each area.The character areas include: the <strong>College</strong> Precinct (Calvert,

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s, and Kent Halls); Trinity Precinct (Church andcemetery); <strong>St</strong>ate House Precinct (<strong>St</strong>ate House area); andRiparian Precinct (Church Point and waterfront).Chapter 6: Landscape Treatment GuidelinesThe treatment guidelines for landscapes address specificlandscape resource issues and opportunities as identified inthe existing conditions analysis. The guidelines are formattedsimilar to the existing conditions chapter and are brokendown by character area and specific landscape categories,such as views, landscape structures, and vegetation.Chapter 7: Recommendations for Cultural LandscapeResourcesThe recommendations for landscape resources providea “broad-brush” overview on caring for, maintaining, andpreserving historic landscape features. The generalizedrecommendations could be applied not only to the studyarea, but to features found throughout the <strong>College</strong>, City, andChurch landholdings.Chapter 8: Existing Conditions: Historic BuildingsChapter 8 includes two distinct sections. The first containsdetailed assessments <strong>of</strong> existing conditions <strong>of</strong> the fourbuildings specifically identified for the project: Calvert Hall,<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Hall, Trinity Church, and the <strong>St</strong>ate House. Thisassessment covers exterior and interior conditions andtouches on additional topics such as life-safety and internalsystems. The second component includes a summary <strong>of</strong>existing conditions and historical significance statementsfor nine other historic buildings located just outside butadjacent to the boundaries <strong>of</strong> the historic sector.Chapter 9: Architectural Treatment GuidelinesGeneral treatment guidelines for specific architecturalmaterials and features commonly found on the buildingsincluded within this report are provided in Chapter 9. Theguidelines address conditions specific to the study areabut can also be applied to buildings outside <strong>of</strong> the studyarea to address maintenance and repair concerns. Thetreatment guidelines cover various building elements suchas concrete, masonry, windows, doors, ro<strong>of</strong>s, and paint.Chapter 10: Building Specific RecommendationsChapter 10 provides detailed recommendations, organizedinto three levels <strong>of</strong> importance, for work necessary at each<strong>of</strong> the four historic buildings: Calvert Hall, <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Hall,Trinity Church, and the <strong>St</strong>ate House. Recommendations arebroken down first by building, then by level <strong>of</strong> importance,Page 1-7

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008and then by building elements. The recommendations areintended to help guide future capital improvement decisionsand prioritize building improvement projects.Chapter 11: Guidelines for New ConstructionChapter 11 discusses guidelines for incorporating newconstruction projects within the historic sector in a mannerthat does not detract from the historical significance <strong>of</strong>surrounding buildings and resources. Additional guidelinesand considerations for incorporating barrier-free accessand environmentally sensitive design solutions are alsoincluded.Page 1-8

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008preservation CONTEXTThe purpose <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is to assist the<strong>College</strong>, City, and Church in preserving and protecting thehistoric integrity <strong>of</strong> resources which symbolize the history andevolution <strong>of</strong> religion, politics, and development in <strong>Maryland</strong>.The legacy <strong>of</strong> colonial <strong>Maryland</strong> lives on in <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Cityand is reflected in the buildings and landscapes withinthe project study area. Preserving those resources todayensures future generations will also have the opportunityto enjoy those resources and that the history <strong>of</strong> the studyarea will continue to live on, even as it may also continue tochange and evolve.This section is intended to provide a basis for understandingthe <strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Maryland</strong>. Understanding the history <strong>of</strong> preservation at<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City and how it has evolved and contributedto the changes associated with resources will help to laythe framework for later recommendations and guidelines.Understanding the basic principles <strong>of</strong> good preservationpractice , known as the Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Interior’s <strong>St</strong>andardsfor the Treatment <strong>of</strong> Historic Properties, will provide decisionmakerswith the tools necessary to make sensitive andinformed decisions. Understanding the intent and meaning<strong>of</strong> different preservation treatments will assist decisionmakersin treating historic resources in an appropriatemanner.The Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Interior’s <strong>St</strong>andardsThe Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Interior established the <strong>St</strong>andardsfor the Treatment <strong>of</strong> Historic Properties (<strong>St</strong>andards) aspart <strong>of</strong> the National Historic <strong>Preservation</strong> Act <strong>of</strong> 1966. The<strong>St</strong>andards provide a philosophical framework to promoteresponsible preservation practices and are intended tohelp inform communities, institutions, and individualsabout pr<strong>of</strong>essional standards for historic preservation. Itis recognized that all preservation efforts, whether throughthe federal government, a local government, or throughprivate efforts, can be informed and enhanced by use <strong>of</strong>the <strong>St</strong>andards. Because they articulate the basic underlyingprinciples that are fundamental to historic preservation,they are <strong>of</strong>ten incorporated into preservation plans, zoningordinances, and regulations that govern historic districts orproperties.The <strong>St</strong>andards were intentionally written to be broad so thatthey can be applied to virtually all types <strong>of</strong> historic resources,including buildings, landscapes, roadways, structures,objects, and archeological sites. The intent <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>andardsPage 1-9

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Page 1-10is to assist in the long-term preservation <strong>of</strong> a building, site, orresource. However, the <strong>St</strong>andards are general in character,and not principles which can be used to make decisionsabout what features <strong>of</strong> any specific building, landscape, orsite should be saved or replaced. Case-by-case decisionsrequire additional direction which goes above and beyondthe framework provided in the <strong>St</strong>andards; it is best to lookat the <strong>St</strong>andards as an approach to sensible preservationplanning, not as the only solution. Although updated fromtime to time, the basic principles <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>andards haveremained consistent and are a testament to the soundness<strong>of</strong> their language (Weeks and Grimmer 1995).The specific language <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>andards can be found inthe United <strong>St</strong>ates Department <strong>of</strong> the Interior, National ParkService, 36 CFR (Code <strong>of</strong> Federal Regulations), Part 67.Hard copies <strong>of</strong> the document are available as publicationsdistributed by the United <strong>St</strong>ates Department <strong>of</strong> the Interior,National Park Service or online at http://www.cr.nps.gov/hps/tps/tax/rhb/stand.htm.The philosophy behind the recommendations and treatmentguidelines for buildings and landscapes included in the<strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> for <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> is based onthe Secretary <strong>of</strong> the Interior’s <strong>St</strong>andards for Rehabilitation,which are a component <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>andards for the Treatment <strong>of</strong>Historic Properties. Because the <strong>St</strong>andards are applicable toanticipated projects at <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong>, Trinity Church, andthe <strong>St</strong>ate House, they have been used as the philosophicalframework for this document.The ten preservation principles which comprise the<strong>St</strong>andards for Rehabilitation are identified below. To assistusers <strong>of</strong> this document in understanding the standards, theyare followed by a short discussion <strong>of</strong> how the standard shouldbe interpreted when undertaking a historic preservationproject.<strong>St</strong>andard 1A property shall be used for its historic purpose or be placedin a new use that requires minimal change to the definingcharacteristics <strong>of</strong> the building and its site and environment.<strong>St</strong>andard 1 encourages property owners and decisionmakersto consider and find uses for historic sites thatenhance the historic character, not detract from it. Thisstandard is directly applicable to reuse projects and advisesthat such projects should be carefully planned to minimizeadverse impacts to the historic character. Destruction <strong>of</strong>character-defining features should be avoided.

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008<strong>St</strong>andard 2The historic character <strong>of</strong> the property shall be retained andpreserved. The removal <strong>of</strong> historic materials or alteration<strong>of</strong> features and spaces that characterize a property shall beavoided.<strong>St</strong>andard 2 emphasizes the importance <strong>of</strong> preservingthe historic materials and features which define a historicproperty. In an effort to retain the historic character <strong>of</strong> aproperty, efforts should be made to repair historic features,as opposed to allowing them to be removed.<strong>St</strong>andard 3Each property shall be recognized as a physical record <strong>of</strong>its time, place, and use. Changes that create a false sense <strong>of</strong>historical development, such as adding conjectural featuresor architectural elements from other buildings, shall not beundertaken.<strong>St</strong>andard 3 acknowledges that historic resources are reallya “snapshot in time,” and therefore discourages combininghistoric features from various properties or constructingnew buildings that falsely read as historic. Reconstruction<strong>of</strong> lost resources, or specific features, should only beundertaken when detailed documentation is available andwhen a resource is <strong>of</strong> such significance that it warrantsreconstruction.<strong>St</strong>andard 4Most properties change over time; those changes that haveacquired historic significance in their own right shall be retainedand preserved.<strong>St</strong>andard 4 recognizes that few buildings remain unchangedover a long period <strong>of</strong> time, and that many <strong>of</strong> these changescontribute to a resource’s significance. Understanding thecumulative history <strong>of</strong> a resource, and how it has evolved, isas important as understanding the origins <strong>of</strong> the resource.This standard should be kept in mind when consideringtreatments for buildings that have undergone changes.The evolution <strong>of</strong> a resource can usually be identified andsignificant, so contributing changes should be retained.The changes that have occurred to the resource are aninteresting way to learn more about, and communicate,the parallel changes that may have occurred in a largercommunity context.Page 1-11

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008<strong>St</strong>andard 5Distinctive features, finishes, and construction techniques orexamples <strong>of</strong> craftsmanship that characterize a property shall bepreserved.<strong>St</strong>andard 5 recommends preserving the distinctive qualities<strong>of</strong> a resource that are representative <strong>of</strong> its overall historiccharacter and integrity. When undertaking a preservationproject, it is important to identify the distinctive features,materials, construction type, floor plan, and details thatcharacterize the property. Every effort should be made toretain these distinctive features in their original form.<strong>St</strong>andard 6Deteriorated historic features shall be repaired rather thanreplaced. Where the severity <strong>of</strong> deterioration requiresreplacement <strong>of</strong> a distinctive feature, the new feature shall matchthe old in design, color, texture, and other visual qualities and,where possible, materials. Replacement <strong>of</strong> missing featuresshall be substantiated by documentary, physical, or pictorialevidence.<strong>St</strong>andard 6 focuses on the importance <strong>of</strong> repairing features,as opposed to replacing them, to the greatest extentpossible. Looking at options and opportunities for repairinga feature should always precede a decision to replacethe feature. In instances where severe deterioration or amissing feature makes repair impossible, new featuresshould match the original as closely as possible. Before anexisting feature is removed for its replacement, it should becarefully documented and photographed as a reference toassist in future decision-making.<strong>St</strong>andard 7Chemical or physical treatments, such as sandblasting, thatcause damage to historic materials shall not be used. The surfacecleaning <strong>of</strong> structures, if appropriate, shall be undertaken usingthe gentlest means possible.<strong>St</strong>andard 7 warns that harsh cleaning alternatives canseverely damage historic fabrics by destroying the material’sphysical properties and speeding the deterioration process.This standard is intended to emphasize the importance<strong>of</strong> considering cleaning alternatives, and choosing thegentlest available cleaning method in an effort to protectand preserve the historic fabric.Page 1-12<strong>St</strong>andard 8Significant archeological resources affected by a project shall beprotected and preserved. If such resources must be disturbed,mitigation measures shall be undertaken.

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008<strong>St</strong>andard 8 addresses the importance <strong>of</strong> historic andprehistoric archeological resources which exist below groundlevel. This is particularly important for new constructionprojects which involve excavation. All new constructionprojects, particularly in areas <strong>of</strong> likely archeologicalresources, should be assessed for archeological potential.When archeological resources are identified, mitigation maybe required.<strong>St</strong>andard 9New additions, exterior alterations, or related new constructionshall not destroy historic materials that characterize the property.The new work shall be differentiated from the old and shallbe compatible with the massing, size, scale, and architecturalfeatures to protect the historic integrity <strong>of</strong> the property and itsenvironment.<strong>St</strong>andard 9 identifies the potential for new additions,alterations, and new construction to negatively impacthistoric features <strong>of</strong> a property. This standard emphasizes theimportance <strong>of</strong> identifying potential impacts and mitigatingthem before they become problematic. All new work isexpected to be compatible with existing resources, thoughit should never replicate the existing historic resource. Aviewer should be able to clearly distinguish new work fromthe original.<strong>St</strong>andard 10New additions and adjacent or related new construction shallbe undertaken in such a manner that if removed in the future,the essential form and integrity <strong>of</strong> the historic property and itsenvironment would be unimpaired.<strong>St</strong>andard 10 stresses the importance <strong>of</strong> sensitive additions,alterations, and new construction. Sensitively designedadditions, alterations, and new construction should bereversible, and should not destroy existing historic fabricand features. This standard reiterates how smart planningcan protect the historic integrity <strong>of</strong> a building or resource(Weeks and Grimmer 1995:162).Page 1-13

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Page 1-14<strong>Preservation</strong> TreatmentsThere are four historic preservation treatment approaches,defined in the <strong>St</strong>andards, which are widely accepted inthe field <strong>of</strong> historic preservation today – <strong>Preservation</strong>,Rehabilitation, Restoration, and Reconstruction (Weeksand Grimmer 1995:2).• <strong>Preservation</strong> treatments require the retention <strong>of</strong>the greatest amount <strong>of</strong> historic fabric.• Rehabilitationtreatments acknowledge the need toalter or add to a property to meet current needs, whilestill maintaining the historic character. Rehabilitationassumes that the property is deteriorated andtherefore provides more latitude with respect toretention and repair <strong>of</strong> historic features.• Restoration focuses on the retention <strong>of</strong> materialsfrom the most significant period in a property’shistory, while allowing the removal <strong>of</strong> materials fromother periods.• Reconstruction provides limited opportunitiesto re-create a non-surviving structure, landscape,building, or object with new materials that replicatethe original, historic materials.Definitions for each <strong>of</strong> the preservation treatments havebeen included below for reference.<strong>Preservation</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> is defined as the act or process <strong>of</strong> applyingmeasures necessary to sustain the existing form, integrity,and materials <strong>of</strong> an historic property. Work, includingpreliminary measures to protect and stabilize the property,generally focuses upon the ongoing maintenance and repair<strong>of</strong> historic materials and features rather than an extensivereplacement and new construction. New exterior additionsare not within the scope <strong>of</strong> this treatment; however, thelimited and sensitive upgrading <strong>of</strong> mechanical, electrical, andplumbing systems and other code-required work to makeproperties functional is appropriate within a preservationproject.<strong>Preservation</strong> stresses the protection, maintenance, andrepair <strong>of</strong> historic fabric and features, and should be thebaseline treatment for all historic resources under theoperation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>College</strong>, the Church, and the City.

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008RehabilitationRehabilitation is defined as the act or process <strong>of</strong> makingpossible a compatible use for a property through repair,alterations, and additions while preserving those portions orfeatures which convey its historical, cultural, or architecturalvalues.Often referred to as adaptive reuse, the key to a rehabilitationproject is to avoid adverse impacts to the historic fabricwhen expanding, modifying, or upgrading facilities. Whenundertaking rehabilitation projects, all entities should takecare in retaining the greatest possible amount <strong>of</strong> historicfabric.RestorationRestoration is defined as the act or process <strong>of</strong> accuratelydepicting the form, features, and character <strong>of</strong> a propertyas it appeared at a particular period <strong>of</strong> time by means <strong>of</strong>the removal <strong>of</strong> features from other periods in its historyand reconstruction <strong>of</strong> missing features from the restorationperiod. The limited and sensitive upgrading <strong>of</strong> mechanical,electrical, and plumbing systems and other code-requiredwork to make properties functional is appropriate within arestoration project.When undertaking restoration projects, the extensivecollection <strong>of</strong> archived historical images and documentationavailable through the <strong>College</strong>, Church, and City, shouldbe referenced to ensure the restoration work is historicallyaccurate.ReconstructionReconstruction is defined as the act or process <strong>of</strong> depicting, bymeans <strong>of</strong> new construction, the form, features, and detailing<strong>of</strong> a non-surviving site, landscape, building, structure, orobject for the purpose <strong>of</strong> replicating its appearance at aspecific period <strong>of</strong> time and in its historic location (Weeksand Grimmer 1995:2).Although reconstruction has previously been utilized in thestudy area with the 1934 <strong>St</strong>ate House project, and Historic<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City has numerous reconstructed buildingson exhibit, it is not anticipated that this is a preservationtreatment that will be used again within the historic campussector.Page 1-15

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Chapter 2:History <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Maryland</strong>INTRODUCTIONThis neck <strong>of</strong> land projecting into the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s River at MillCreek is host to three institutions: Trinity Episcopal Church,<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>, and Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City.The histories <strong>of</strong> these neighboring and overlapping entitieshave been intertwined since Trinity Church first beganusing the abandoned <strong>St</strong>ate House in the early eighteenthcentury, and later sold land to establish the school in 1844.Both church and college have grown to their present sizesin the knowledge that they stand upon the historic site <strong>of</strong><strong>Maryland</strong>’s first capital city.The following chapter is arranged chronologically todocument the colonial-period history <strong>of</strong> the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Citypeninsula, followed by detailed histories <strong>of</strong> Trinity Church,<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s Seminary/<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>, andHistoric <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City.HISTORIC PERIODSEarly Colonial SettlementThe shores <strong>of</strong> the southern Chesapeake were first exploredby English traders in the early 1600s. Of greatest significancein the history <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City were the explorations <strong>of</strong>Captain Henry Fleet (1600-1660), a native <strong>of</strong> Kent. Fleetfirst arrived in the New World in 1621, initially visiting theJamestown settlement in Virginia before traveling north toexplore the Potomac region. In 1623, he was captured byAlgonquians and spent the following four years living withthe Nacotchtank tribe, where he gained great understanding<strong>of</strong> local dialects and cultural practices. Aware that Englishmerchants had a great demand for furs, and that theIndians had an increasing desire for European goods, Fleetfacilitated the beginnings <strong>of</strong> a fur trade in 1627-1632. Hedealt frequently with the Yaocomico tribe, who lived in villagesalong the <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s River, making him the first Englishmanknown to have resided in the area. With his brothers, Fleetsoon had a successful trading venture that exported beaverpelts, maize, and fish out <strong>of</strong> southern <strong>Maryland</strong> and importedPage 2-1

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008European goods for the native tribes (Fausz 1990:11-12).Fleet’s knowledge <strong>of</strong> local tribes and skill in dealingdiplomatically with the native inhabitants quickly brought himto the attention <strong>of</strong> Governor Leonard Calvert, who arrivedin the New World in 1634 with 150 colonists on the shipsArk and Dove, to establish a <strong>Maryland</strong> colony. While thecolonists camped temporarily at <strong>St</strong>. Clement’s Island, Fleetassisted Calvert as an interpreter and was instrumentalin locating a site for the new colony and negotiating itspurchase. The site was part <strong>of</strong> the Yaocomico lands, andthis small tribe was eager to sell a parcel to the English inexchange for goods and the promise <strong>of</strong> protection againstthe Susquehannocks. Calvert purchased “thirtie miles” <strong>of</strong>prime land from the Yaocomicoes in exchange for a quantity<strong>of</strong> English goods, namely hatchets, axes, hoes, and clothing.According to legend, the transaction was conducted beneatha large mulberry tree which stood on the bluff near ChurchPoint until 1883. A monument to the memory <strong>of</strong> LeonardCalvert in the Trinity Church cemetery marks the site <strong>of</strong> themulberry tree (Fausz 1990:12).Governor Leonard Calvert’s arrival to establish a <strong>Maryland</strong>colony was the culmination <strong>of</strong> many years <strong>of</strong> efforts byhis father, George Calvert (ca. 1580-1632), the first LordBaltimore, and his older brother, Cecilius Calvert, thesecond Lord Baltimore, to found a colony in the New World.George Calvert’s wealthy family was repeatedly persecutedby the Anglican government during his youth for practicingCatholicism. The Calverts appear to have renouncedCatholicism for a time, and both George and his fathersubsequently rose to political <strong>of</strong>fice, a privilege denied topracticing Catholics. In 1624, George publicly announcedhe had become a Catholic and resigned his position asSecretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>St</strong>ate. Despite this, King James made himBaron <strong>of</strong> Baltimore, and Calvert turned his attention towardestablishing a new colony in America. His nine-year attemptto found a settlement at Avalon in Newfoundland proveddisastrous, and in 1629 he abandoned the project andremoved his colonists to Virginia before returning to England.Although the Calvert colonists, as Catholics, were greetedcoolly in Virginia, Calvert explored unsettled areas <strong>of</strong> theChesapeake and liked what he saw. Upon his return home,he petitioned King Charles I for a land grant north <strong>of</strong> Virginiaand, drawing upon lessons learned in Newfoundland, drewup a charter, but died before it was executed (Hammett1990:1-3).Page 2-2George Calvert’s eldest son Cecilius, or Cecil, inherited histitle and received the <strong>Maryland</strong> charter from the King in June1633, two months after his father’s death. The charter gavethe second Lord Baltimore title to millions <strong>of</strong> acres, but Cecil

<strong>St</strong>. Mary’s <strong>College</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong><strong>Preservation</strong> <strong>Master</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>Historic <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s City February 2008Calvert was forced to attract investors to make the venturea success. He drew up Conditions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>tation to specifywhat colonists would be granted in return for their effortsto bring workers and families into the colony. Potentialcolonists were also given a letter <strong>of</strong> instruction, designedto ensure peace in the colony and diplomatic relations withother colonies. On November 22, 1633, two ships, the Arkand the Dove, sailed toward the New World. Cecil Calvertdispatched his younger brother, Leonard, to accompanythe colonists and serve as the first Governor (Hammett1990:3-5; Miller 2003:225).Detail, George Alsop map <strong>of</strong> <strong>Maryland</strong>, ca. 1666 (Fausz 1990:13).The new <strong>Maryland</strong> colony was a promising site, featuringfields already planted with corn by the Indians and barklonghouses for shelter. Two bays, a good water supply,and a defensible high bluff were desirable geographicfeatures. The Yaocomicoes relocated to Pagan Pointnearby, and the friendly relations between the colonists andthe local tribes begun by Henry Fleet endured for years tocome. The mutual respect shown by these seventeenthcentury<strong>Maryland</strong>ers and the Piscataways was an early andsignificant example <strong>of</strong> enlightened liberal thought and openmindedness,and reflected the principles <strong>of</strong> tolerance desiredby George Calvert. The deliberately nonsectarian colonyat <strong>St</strong>. Mary’s was a daring attempt to create a society thatPage 2-3