Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SPECIAL REPORT > AUDIO<br />

SOUND<br />

APPEAL<br />

Sound designers talk shop<br />

at the Tribeca Film Festival<br />

by Daniel Loria<br />

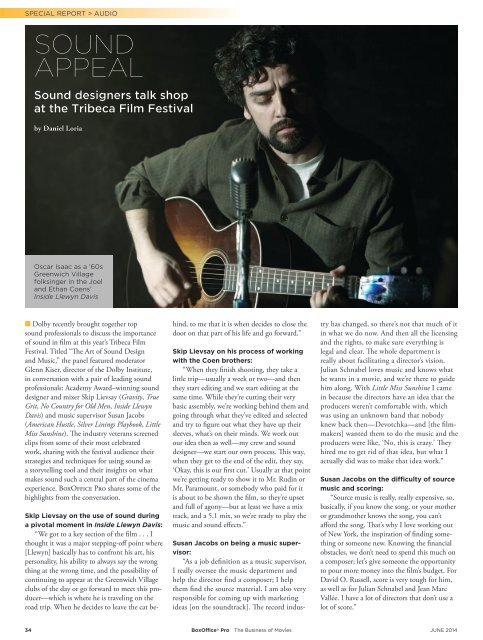

Oscar Isaac as a ’60s<br />

Greenwich Village<br />

folksinger in the Joel<br />

and Ethan Coens’<br />

Inside Llewyn Davis<br />

n Dolby recently brought together top<br />

sound professionals to discuss the importance<br />

of sound in film at this year’s Tribeca Film<br />

Festival. Titled “The Art of Sound Design<br />

and Music,” the panel featured moderator<br />

Glenn Kiser, director of the Dolby Institute,<br />

in conversation with a pair of leading sound<br />

professionals: Academy Award–winning sound<br />

designer and mixer Skip Lievsay (Gravity, True<br />

Grit, No Country for Old Men, Inside Llewyn<br />

Davis) and music supervisor Susan Jacobs<br />

(American Hustle, Silver Linings Playbook, Little<br />

Miss Sunshine). The industry veterans screened<br />

clips from some of their most celebrated<br />

work, sharing with the festival audience their<br />

strategies and techniques for using sound as<br />

a storytelling tool and their insights on what<br />

makes sound such a central part of the cinema<br />

experience. BoxOffice <strong>Pro</strong> shares some of the<br />

highlights from the conversation.<br />

Skip Lievsay on the use of sound during<br />

a pivotal moment in Inside Llewyn Davis:<br />

“We got to a key section of the film . . . I<br />

thought it was a major stepping-off point where<br />

[Llewyn] basically has to confront his art, his<br />

personality, his ability to always say the wrong<br />

thing at the wrong time, and the possibility of<br />

continuing to appear at the Greenwich Village<br />

clubs of the day or go forward to meet this producer—which<br />

is where he is traveling on the<br />

road trip. When he decides to leave the cat behind,<br />

to me that it is when decides to close the<br />

door on that part of his life and go forward.”<br />

Skip Lievsay on his process of working<br />

with the Coen brothers:<br />

“When they finish shooting, they take a<br />

little trip—usually a week or two—and then<br />

they start editing and we start editing at the<br />

same time. While they’re cutting their very<br />

basic assembly, we’re working behind them and<br />

going through what they’ve edited and selected<br />

and try to figure out what they have up their<br />

sleeves, what’s on their minds. We work out<br />

our idea then as well—my crew and sound<br />

designer—we start our own process. This way,<br />

when they get to the end of the edit, they say,<br />

‘Okay, this is our first cut.’ Usually at that point<br />

we’re getting ready to show it to Mr. Rudin or<br />

Mr. Paramount, or somebody who paid for it<br />

is about to be shown the film, so they’re upset<br />

and full of agony—but at least we have a mix<br />

track, and a 5.1 mix, so we’re ready to play the<br />

music and sound effects.”<br />

Susan Jacobs on being a music supervisor:<br />

“As a job definition as a music supervisor,<br />

I really oversee the music department and<br />

help the director find a composer; I help<br />

them find the source material. I am also very<br />

responsible for coming up with marketing<br />

ideas [on the soundtrack]. The record industry<br />

has changed, so there’s not that much of it<br />

in what we do now. And then all the licensing<br />

and the rights, to make sure everything is<br />

legal and clear. The whole department is<br />

really about facilitating a director’s vision.<br />

Julian Schnabel loves music and knows what<br />

he wants in a movie, and we’re there to guide<br />

him along. With Little Miss Sunshine I came<br />

in because the directors have an idea that the<br />

producers weren’t comfortable with, which<br />

was using an unknown band that nobody<br />

knew back then—Devotchka—and [the filmmakers]<br />

wanted them to do the music and the<br />

producers were like, ‘No, this is crazy.’ They<br />

hired me to get rid of that idea, but what I<br />

actually did was to make that idea work.”<br />

Susan Jacobs on the difficulty of source<br />

music and scoring:<br />

“Source music is really, really expensive, so,<br />

basically, if you know the song, or your mother<br />

or grandmother knows the song, you can’t<br />

afford the song. That’s why I love working out<br />

of New York, the inspiration of finding something<br />

or someone new. Knowing the financial<br />

obstacles, we don’t need to spend this much on<br />

a composer; let’s give someone the opportunity<br />

to pour more money into the film’s budget. For<br />

David O. Russell, score is very tough for him,<br />

as well as for Julian Schnabel and Jean Marc<br />

Vallée. I have a lot of directors that don’t use a<br />

lot of score.”<br />

34 BoxOffice ® <strong>Pro</strong> The Business of Movies JUNE <strong>2014</strong>