Stavanger kommune

Stavanger kommune

Stavanger kommune

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

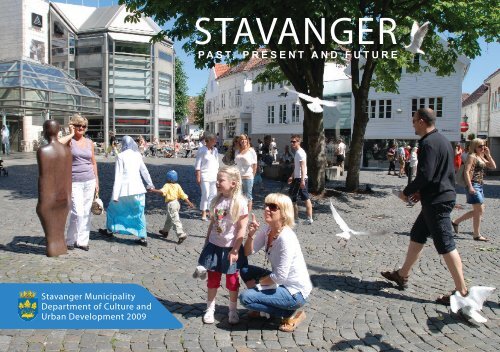

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Municipality<br />

Department of Culture and<br />

Urban Development 2009<br />

STAVANGER<br />

PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

STAVANGER<br />

PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Municipality<br />

Department of Culture and<br />

Urban Development 2009

Introduction<br />

This is not a history book, nor is it a catalogue for those with<br />

a special interest in culture, architecture and town planning.<br />

It is a short introduction into how the city has become what<br />

we see today and what it may become in the future.<br />

Many members of the Department of Culture and Urban Development,<br />

and some from other departments in the <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

Municipality, have contributed text and illustrations. Together,<br />

we have made a short presentation of examples from<br />

the city’s physical development and plans for the future. The<br />

examples can be an expression of an era, a mood or a stage<br />

in the continuous development of the city. They may be symbols,<br />

places which have become part of <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s identity.<br />

In this way we hope to show some of what we feel is special<br />

about <strong>Stavanger</strong>, both old and new.<br />

The first edition of this book was one of the Department of<br />

Culture and Urban Development’s contributions to <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

as European Capital of Culture 2008 (“<strong>Stavanger</strong> 2008”). We<br />

hope this translation will be useful and enjoyable for visitors<br />

to the city.<br />

Per Jarle Solheim has written several of the chapters and developed<br />

the manuscript. Egil Bjørøen has been responsible<br />

Vågen seen from Valberget 2008<br />

4

Vågen seen from Valberget. Photo: C. L. Jacobsen, 1870s<br />

for the layout, design and some of the illustrations. Jorunn<br />

Imsland has provided most of the illustrations and the maps.<br />

Unless specified otherwise, the photographs have been taken<br />

by Siv Egeli. Thommas Bjerga has supervised production<br />

of the book. Brenda Solheim has translated the book into<br />

English.<br />

Department of Culture and Urban Development<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>, 1 June 2009<br />

Halvor S. Karlsen<br />

Director

List of Contents<br />

PAGE 7 CITY EXPANSION<br />

PAGE 8 A SHORT HISTORY OF THE CITY<br />

PAGE 14 STAVANGER ON THE MAP<br />

PAGE 16 STAVANGER IN NUMBERS<br />

PAGE 18 TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

PAGE 32 CITY EXPANSION IN 1965 AND<br />

URBAN DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

PAGE 42 TRANSPORT AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT<br />

PAGE 44 GLIMPSES OF THE NEW STAVANGER<br />

PAGE 52 GREEN AREAS IN STAVANGER<br />

PAGE 54 TWO MAJOR TOWN PLANNING<br />

COMPETITIONS<br />

PAGE 60 TWO MAJOR CENTRAL DEVELOPMENT<br />

AREAS<br />

PAGE 66 CULTURE IS URBAN DEVELOPMENT<br />

PAGE 78 NORWEGIAN WOOD<br />

PAGE 80 VIEWS AND WALKS<br />

PAGE 84 PLANNING A CITY<br />

PAGE 86 THE FUTURE<br />

PAGE 88 SOURCES<br />

6

City Expansion<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> has developed from a small village round the harbour<br />

and adjacent area (Vågen and Østervåg) in the 12th century<br />

to become the fourth largest city in Norway. The city’s<br />

boundaries have been moved several times to accommodate<br />

population growth and commercial activities.<br />

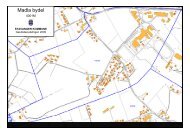

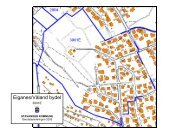

As the map shows, growth was modest until 1866. The largest<br />

expansion occurred in 1965 when Madla municipality<br />

and parts of Hetland municipality were incorporated into<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>.<br />

Vågen seen from Valberget. Photo: C. L. Jacobsen 1869

A Short History of the City<br />

It is not without reason that the slogan for<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> 2008 was Open Port. The harbour<br />

and the sea have always been important.<br />

Vågen (the inner harbour), protected<br />

from the open ocean, was a natural starting Fishing-net sinker<br />

point for a port town. People have lived in<br />

what is now <strong>Stavanger</strong> as far back as the Stone Age. The first<br />

visible signs of habitation are rock carvings from the Bronze<br />

Age. However, it took a long time from about 1000 B.C.,<br />

when the first carvings were chiselled into the rock at Rudlå,<br />

until <strong>Stavanger</strong> became an important city.<br />

It is difficult to establish when <strong>Stavanger</strong> became a town or a<br />

city. Little is known of the period before approximately 1125<br />

when building of the cathedral (Domkirken) started on the<br />

hill between Vågen and Breiavatnet. <strong>Stavanger</strong> was given to<br />

the church in 1164 and was an important clerical centre in the<br />

Middle Ages. Even though town privileges were awarded in<br />

1425, the population at the beginning of the 16th century was<br />

no more than about 100, the majority of whom were connected<br />

to the church.<br />

Iron age farm, Ullandhaug<br />

Bronze Age rock carvings, Rudlå<br />

In the mid 16th century, there was a large international demand<br />

for timber and export of timber from Ryfylke to continental<br />

Europe laid the foundation for expansion. The first<br />

commercial firms and ship owners were established. <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

became the administrative centre for <strong>Stavanger</strong> County<br />

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE CITY<br />

8

in 1568 and was granted a town charter in 1594. By that<br />

stage, the population had increased to 600.<br />

At the beginning of the 19th century, natural resources<br />

and international trade - the incredible herring fisheries<br />

and market for herring in Europe - provided the basis for<br />

enormous growth, particularly after free world trade was<br />

established in 1850. In the second half of the 19th century,<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> had the second largest commercial fleet in<br />

the country, with 600 ships in foreign trade, and was the<br />

centre of one of the country’s most important shipbuilding<br />

areas. Large trading and shipping companies were<br />

established.<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> cathedral<br />

The walls of the Kongsgård school are as old as the cathedral and the<br />

Utstein monastery, and one of very few buildings in the region from that<br />

period

The population grew from 2 500 in<br />

1800 to 30 000 a hundred years later.<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> became a large town by<br />

the standards of the time, with the<br />

cultural and material ambitions of a<br />

large city.<br />

By the late 19th century, the period<br />

of growth had in reality ended. The<br />

herring disappeared in about 1870.<br />

The freight market stagnated and<br />

almost disappeared during the next<br />

decade and the town went into a<br />

deep recession.<br />

In about 1890 a new business came into existence, the canning<br />

industry. The raw material was brisling from the fjord. In the<br />

course of a few decades, tinned brisling from <strong>Stavanger</strong> became<br />

one of the country’s most important export products. At the outbreak<br />

of the First World War, <strong>Stavanger</strong> was one of the leading<br />

industrial towns in Norway. Shipbuilding and maintenance was<br />

an important industry as well as the canning industry and its<br />

subcontractors.<br />

Sardine packing at Egeland’s canning factory, Hillevåg. Photo: H. Johannesen, ca 1910<br />

Ship under construction at Rosenberg. Photo: O. Gulliksen, ca 1920<br />

International crises in the period between the two World Wars<br />

also affected <strong>Stavanger</strong>. Many firms struggled and several local<br />

banks went bankrupt. However, this was a relatively short recession<br />

and by the end of the 1930s the town was on the rise again.<br />

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE CITY<br />

10

Herring in Vågen. C. Lutcherath, ca 1910

Drill bit, Norwegian<br />

Petroleum Museum<br />

The town was relatively undamaged during<br />

the Second World War and continued to grow<br />

until the 1960s, when demand for canned<br />

food decreased and competition within<br />

shipbuilding was hard. The town was<br />

heading for a new recession.<br />

The discovery of oil in the North Sea<br />

started a new period of growth. The<br />

first major oil field, Ekofisk, was<br />

discovered in the autumn of 1969.<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> became the administrative<br />

and technical centre for North Sea oil<br />

activity. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (Oljedirektoratet)<br />

was established in <strong>Stavanger</strong> and national and international<br />

oil companies set up offices. The Norwegian State’s national<br />

oil company (Statoil) became the largest employer. Major oil<br />

installations were constructed at Rosenberg and Jåttåvågen.<br />

After the end of major construction activity, growth continued<br />

in the service industry and administration, with great cumulative<br />

effect.<br />

Amalgamation of the <strong>Stavanger</strong> municipality with Madla and<br />

parts of Hetland in 1965 enabled <strong>Stavanger</strong> to expand and keep<br />

pace with the growth, and to establish new districts. The first<br />

general plan for the amalgamated area was approved in 1968.<br />

Platform construction. Photo: A. Brueland 1973<br />

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE CITY<br />

12

The planning basis was thereby ready to meet new challenges<br />

and further growth which resulted from major oil and<br />

gas discoveries. Many essential features of the plan have<br />

been implemented in establishing green areas, development<br />

areas and main roads.<br />

Prosperity is still increasing in the entire greater <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

area. There are today no clear divisions between <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

and the neighbouring municipalities of Sandnes, Sola and<br />

Randaberg and cooperation between the municipalities<br />

is developing strongly. The Forus area, which is located<br />

centrally at the junction of <strong>Stavanger</strong>, Sandnes and Sola, is<br />

perhaps the clearest example of cooperation with respect to<br />

area planning.<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> has been become a prosperous and international<br />

city, with a dynamic commercial and cultural life and high<br />

ambitions. The city became a university town on 1 January<br />

2005. The city has also received several civic awards, such<br />

as the Synergy Prize in 2001, Ossietzky Prize, Norwegian<br />

Cultural Municipality and Norwegian Sports Municipality<br />

in 2003, Best Host Town of Tall Ships Race 2004, International<br />

Municipality 2004 and Urban Environment Prize in<br />

2005 and 2006.<br />

Summer in Byfjorden

<strong>Stavanger</strong> on the Map<br />

Town Secretary Ulrik Frederik Aagaard’s map from 1726 is<br />

the oldest map of <strong>Stavanger</strong>. However, the town did not have<br />

technical mapping and surveying expertise until after the fire<br />

at Holmen in 1860 when first lieutenant Hielm in Kristiania<br />

(now Olso) was contracted to survey the area.<br />

As a result of the fire in 1860, water and gas works were<br />

established, the fire department was organized on a permanent<br />

basis and, in 1866, a position for a town engineer was<br />

established. It was not until 1901 that a combined position for<br />

Below: Surveyor’s certificate of plot area measure<br />

Right: <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s first theodolite<br />

STAVANGER ON THE MAP<br />

14

technical director and head of building development was<br />

established. A separate building development department<br />

was established in 1916. However, the Town Engineer did<br />

not recommend establishing a separate entity for planning<br />

and surveying until 1931. In 1952 the Council voted to<br />

establish the surveying department as a separate service and<br />

to establish a position of Chief Surveyor.<br />

The first series of maps at 1:500 scale was constructed in<br />

the 1950s. They were then photographed as the basis for<br />

maps at 1:1000. In the 1970s, a street name map was created<br />

for use internally within the municipality.<br />

In 1992 it was decided that the City<br />

Surveyor’s department should establish digital<br />

mapping data bases, including property<br />

maps. The coordinate system was recalculated<br />

(Euref 89) and implemented in 1998. At<br />

the same time, the mapping data bases were<br />

made accessible for internal and external use.<br />

Maps have now become “consumables” and<br />

anyone who has access to Internet also has<br />

access to a current map, updated every night.<br />

Theodolite, robot station with GPS 3D model of the area round the county court house GPS

<strong>Stavanger</strong> in Numbers<br />

The following diagram shows the current distribution of<br />

land use within <strong>Stavanger</strong>:<br />

Housing<br />

“Trehusbyen”<br />

City centre<br />

Industry and commerce<br />

Transformation areas<br />

Public buildings<br />

Public outdoor recreation<br />

Agriculture and nature<br />

Transport<br />

Other<br />

Approximately a third is housing. Just about one half is<br />

not built up and includes farmland, natural and recreational<br />

areas. However, it should be noted that many of <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s<br />

inhabitants work outside the city limits and that municipalities<br />

in the region are in practice one market for employment,<br />

housing and commerce.<br />

Right: Growth is distributed unevenly between the individual districts<br />

STAVANGER IN NUMBERS<br />

16

Other<br />

Poland<br />

Health and<br />

social services<br />

Other social and<br />

personal services<br />

Agriculture etc<br />

Industry, oil and<br />

gas production<br />

Afghanistan<br />

Finland<br />

Burma<br />

Lithuania<br />

Indonesia<br />

U.K.<br />

Turkey<br />

Education<br />

Building and<br />

construction<br />

Sri Lanka<br />

Chile<br />

Eritrea<br />

Holland<br />

Somalia<br />

Germany<br />

State, county and<br />

municipality<br />

Office and<br />

administration<br />

etc.<br />

Finance and<br />

insurance<br />

Transport and<br />

communication<br />

Shops, hotels<br />

and restaurants<br />

Ethiopia<br />

Serbia<br />

China<br />

Iraq<br />

France<br />

Thailand<br />

Philippines<br />

Russia<br />

Iran<br />

USA<br />

India<br />

Bosnia-Herzegovina<br />

Denmark<br />

Sweden<br />

Vietnam<br />

Pakistan<br />

A large portion of the jobs in <strong>Stavanger</strong> are associated with<br />

the oil industry or the industrial and administrative sectors,<br />

as shown in the diagram above. At the other end of the scale<br />

are agriculture, forestry and fishing (“Agriculture etc.”).<br />

People from <strong>Stavanger</strong> are often called “siddiser”,<br />

probably a Norwegian version of the English citizen,<br />

originating in the shipping era. At present, 12.5% of<br />

the inhabitants are immigrants. The above diagram<br />

indicates where these 15 000 new “siddiser” come<br />

from. The largest 20 groups are specified, but over<br />

130 other nationalities are included in “Others”.

Traces until 1965<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>’s history has left visible traces which we can still<br />

see today. Individual buildings and areas are witnesses to and<br />

symbols of different phases of development.<br />

King Sigurd Jorsalfar established the <strong>Stavanger</strong> bishopric in<br />

1125 and this is considered to be the year in which <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

was founded. <strong>Stavanger</strong> may have been selected because of its<br />

natural harbour, located closest to England. <strong>Stavanger</strong> became<br />

an ecclesiastic centre, with monastery, school and bishop’s<br />

residence. However, after stagnating for many years, the bishopric<br />

was moved to Kristiansand in 1682 and a bishopric was<br />

not re-established in <strong>Stavanger</strong> before 1925.<br />

Many of <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s historical buildings have been lost, due in<br />

part to changes in society’s structure and values. The St. Olav<br />

monastery which lay west of Breivatnet fell into ruin after the<br />

Reformation and all traces were removed in 1577 when the<br />

monastery was used as a stone quarry. After existing for more<br />

than 500 years, the latin school was demolished in 1842. The<br />

Maria church was used as the town hall and finally a fire station,<br />

before it was pulled down in 1883.<br />

However, the cause of the greatest destruction historically has<br />

been fire. Most of the buildings were timber and fires were<br />

catastrophic. Between 1633 and 1833, large parts of the town<br />

were burnt to the ground as many as seven times.<br />

Eastern facade of the cathedral. Photo: C.J. Jacobsen, ca 1910<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

18

Cathedral<br />

Building of the cathedral in romanesque style started in<br />

about 1125 under Bishop Reinald from Winchester in England.<br />

The building was seriously damaged by fire in 1272.<br />

During its reconstruction, the cathedral was expanded by<br />

adding a choir in gothic style and acquired its current form.<br />

The cathedral was renovated extensively between 1939<br />

and 1964. In connection with this work, led by Gerhard<br />

Fischer, the plaster was removed and the cathedral largely<br />

restored to its medieval appearance.<br />

Valberg Tower<br />

After the fire of 1833, it was decided to build a watchtower<br />

for the town’s firemen at Valberget, the highest point on<br />

Holmen, with an overview of the whole town at the time.<br />

The Valberg tower (Valbergtårnet), designed by the palace<br />

architect, Christian Grosch, was completed in 1853.<br />

The tower was never very successful in terms of fire<br />

protection. Following the next fire in 1860, when 210 houses<br />

at Holmen burnt to the ground, only the new fire tower<br />

was left standing. However, even though the Valberg tower<br />

never served its original purpose, the building, with its<br />

beautiful shape and commanding position, has become an<br />

important symbol of <strong>Stavanger</strong>.<br />

Between 1800 and 1900, the population increased tenfold.<br />

This, as well as modern technology and external influences,<br />

changed <strong>Stavanger</strong> completely in many areas. Banks, Valberg tower from the north-west. Photo: G. Wareberg 1917

gasworks, waterworks, railway, telephone, missionary societies,<br />

temperance society and newspaper were established. Cultural<br />

life flourished. The author Alexander Kielland, the artist<br />

Kitty Kielland and lyric poet Sigbjørn Obstfelder are perhaps<br />

the most well-known cultural figures from this period.<br />

“Acropolis”<br />

Prosperity gave <strong>Stavanger</strong> a new self-respect, which culminated<br />

in the construction of four large public buildings between<br />

1883 and 1897, the Rogaland Theatre (Rogaland Teater)<br />

(1883), <strong>Stavanger</strong> gymnastics hall (<strong>Stavanger</strong> Turnhall) (1891),<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Museum (1893) and <strong>Stavanger</strong> hospital (<strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

sykehus) (1897). All of these were dedicated to culture and<br />

the welfare of the people, all were designed by the <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

architect Hartvig Sverdrup Eckhoff and all were located on the<br />

hill above the town as it was at the time, a local “Acropolis”.<br />

The water supply for the hospital came from Mosvannet via a<br />

water tank at Våland and, from 1895, the Våland tower became<br />

a landmark. All this building activity was an enormous economic<br />

effort, perhaps the greatest investment in public welfare in<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> to date. Remarkably, this coincided with the onset<br />

of a serious depression following the collapse of the herring<br />

fisheries and shipping industry. All the major shipowners and<br />

businesses went bankrupt during the 1880s.<br />

Museum, gymnastics hall and theatre. Photo: C.J. Jacobsen 1901<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> hospital. Photo: M. Eckhoff 1897<br />

Today, the Rogaland Theatre has taken over the gymnastics<br />

hall and most of the hospital is used as Rogaland County Council<br />

offices. However, the buildings bear witness to civic pride,<br />

vision and faith in the future.<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

20

”Acropolis” 2008<br />

Below: <strong>Stavanger</strong> Museum. Right: Rogaland Theatre

Breiavatnet and Byparken<br />

Breiavatnet has many names – the heart of the city, the city’s<br />

smiling eye – and has a special place in the city’s consciousness.<br />

Breiavatnet was part of Vågen until approximately 3 000 years<br />

ago, when the land rose (or the sea sank). At that time people<br />

were carving rock signs at Rudlå. The lake lay outside of the<br />

built-up area until the 19th century and just inside the town<br />

boundary until it was expanded in 1878.<br />

The town park was established as a public park in about 1870.<br />

Today, the city benefits from this wise decision.<br />

The park has beautiful trees, well-maintained beds of flowers<br />

and one of <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s most distinctive buildings. In 1915 an<br />

architectural competition was held for design of a music pavilion<br />

next to the cathedral. The winner was architect Erling<br />

Nielsen of Kristiania. This modest, but well-designed, building<br />

was completed in 1925 and fits in with the cathedral and green<br />

area of Kongsgård.<br />

Breiavatnet towards the railway station. Photo: A. Brueland 1970<br />

Music pavilion, 1920s<br />

Breiavatnet. Photo: Bitmap<br />

Together with Vågen, Breiavatnet is still the strongest natural<br />

feature in the city centre, even though landfills have changed<br />

its original appearance. <strong>Stavanger</strong> would have been poorer<br />

without the park and Breiavatnet with its promenade in the<br />

middle of the city.<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

22

The Advent of Two-family Houses<br />

In the mid 19th century, <strong>Stavanger</strong> was a compact town,<br />

concentrated in the areas close to the sea between Bjergsted<br />

and Spilderhaug (Badedammen). This area largely coincides<br />

with the area which is considered to be the centre of<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> today.<br />

By the end of the 19th century, all the area available for<br />

building had been taken into use. However, no tenement<br />

blocks were built. Instead, the built-up area had started to<br />

expand towards Storhaug and Våland, and horizontally<br />

divided 2-family timber houses became the most common<br />

type of dwelling, both in this area and in later expansion<br />

up to the 1950s. The new districts were equipped with big<br />

prestigious school buildings. In the eastern part of town,<br />

new industries were established. Just south of town, the<br />

industrial area Hillevåg was established. The Rosenberg<br />

shipyard moved from Bjergsted to Buøy and accelerated<br />

development there.<br />

Morning at Mosvannet. Photo: H. Henriksen, ca 1915<br />

Våland from the mid-1930s. Photo: Widerøe<br />

Mosvatnet and Vålandskogen<br />

Mosvatnet and Vålandshaugen were incorporated into the<br />

town in 1866 and 1905 respectively. Large parts of Våland<br />

have subsequently become built-up. However, trees were<br />

planted in what is now Vålandskogen and around Mosvatnet<br />

lake and have become a resource for the city.

The Wooden Town (Trehusbyen)<br />

The concept of protection, which was established in the<br />

1950s, has subsequently developed and become stronger. One<br />

expression of this is preservation of the so-called Trehusbyen,<br />

which lies largely within the pre-1923 town limits. See the<br />

map on page 7.<br />

In <strong>Stavanger</strong>, as in other Norwegian towns, a large portion<br />

of the houses are timber constructions. Even though brick<br />

buildings appeared following the fires in the town centre in<br />

the 19th century, use of such material had as much to do with<br />

the building’s size and use as with fire safety. Wooden houses<br />

continued to dominate in the centre and in the new districts<br />

established as the city grew.<br />

Sporadic attempts were made to impose use of brick.<br />

However, these efforts did not succeed, primarily because of<br />

the cost. Brick was reserved for churches, factory buildings<br />

and other large buildings.<br />

Two-family houses, Våland<br />

Brick buildings, Wessels gate (left) and St. Petri (right). Photos: Egil Bjørøen<br />

With approximately 8 000 wooden houses from the period<br />

before 1950, <strong>Stavanger</strong> is the city with the largest number of<br />

wooden houses in Europe. It is truly a wooden city, and Trehusbyen<br />

is a natural description and name.<br />

Opposite: Wooden housing, Storhaug<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

24

Awareness of the value of the wooden buildings is relatively<br />

new. In the 1940s, the municipality prepared comprehensive<br />

plans for modernizing the centre. The plans implied complete<br />

clearance of the existing buildings in the centre and at Straen.<br />

Only the cathedral, Kongsgård and the old post office were to<br />

be left standing.<br />

The first projects carried out in line with the clearance plans<br />

(Klubbgata, Olavskleiva) provoked protests. These resulted<br />

in a conservation plan for Straen, or ”Old <strong>Stavanger</strong>” (Gamle<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>), in 1956. This was one of the first conservation<br />

plans in the country and was extremely important for subsequent<br />

town planning in <strong>Stavanger</strong>. Architect Einar Hedén was<br />

central in this work. The plan has been expanded several times<br />

and it is now acknowledged that not only the city centre, but<br />

also all the wooden buildings in central districts, are important<br />

to <strong>Stavanger</strong>.<br />

The wharf warehouses are also an important part of<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>’s character. The herring period from about 1800–<br />

1880 changed the towns’s appearance in the shape of a<br />

continuous row of 200–300 warehouses from Sandvigå to<br />

Strømsteinen.<br />

When the herring disappeared, many of the warehouses were<br />

abandoned or were converted for other uses such as canning<br />

Above: Old <strong>Stavanger</strong>, Nedre Strandgate<br />

Below: Old <strong>Stavanger</strong>, Øvre Strandgate<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

26

factories. Only approximately 60 still remain and many have<br />

changed shape or facade over time. In addition, they now lie<br />

some distance from the water following repeated landfills<br />

along the harbour front. However, they are still a visible<br />

and characteristic feature of the city. Many are now used as<br />

restaurants, pubs and discos, others as shops, storerooms or<br />

offices. It was not until 1993 that a complete register of the<br />

remaining warehouses was compiled and specific conservation<br />

regulations introduced.<br />

The row of wharf warehouses ca 1870 (<strong>Stavanger</strong> Cultural Heritage Office)<br />

Reconstructed on the basis of Torstrup’s map and old photographs by<br />

Helge Schelderup (Vågen) and Unnleiv Bergsgard (eastern harbour)<br />

Row of warehouses today, Skagenkaien towards Millennium Site

The conservation work has now also been applied to other<br />

districts with newer buildings. The most comprehensive work<br />

is the introduction of regulations for Trehusbyen, as defined<br />

in the Cultural Heritage Plan (Kulturminneplanen) in 1995.<br />

Specific aesthetic guidelines for Trehusbyen were introduced in<br />

2003. The municipality’s objective is to preserve this as an area<br />

with wooden buildings, both by preserving existing buildings<br />

and by constructing new buildings in wood.<br />

Two-family house, Våland<br />

Opposite: Inquisitive tourists in Øvre Strandgate<br />

Map showing ”Trehusbyen”<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

28

After the Second World War, Norway was to be rebuilt. An<br />

idealistic generation of planners and architects were to give the<br />

towns more and better houses, new jobs, and green areas for<br />

the inhabitants. Terrace houses, where everyone had access to a<br />

garden, and blocks with large open areas were built outside the<br />

old town centre.<br />

There was a great shortage of houses and the standard of the<br />

older housing was poor. Housing cooperatives were one means<br />

of alleviating the housing shortage and the <strong>Stavanger</strong> Cooperative<br />

Building and Housing Association (SBBL) was established<br />

in 1946.<br />

The terrace house, also called the <strong>Stavanger</strong> House, was developed<br />

in about 1950. It became a trademark of housing<br />

construction in the 1950s and for SBBL’s early Cooperative<br />

Housing Societies. The house was based on a construction with<br />

economic spans and no internal load bearing walls and was<br />

simple and cheap to build. All the houses have an entrance at<br />

street level and their own garden. With two floors plus basement<br />

and attic, three bedrooms and practical kitchens, these<br />

were ideal family dwellings.<br />

Terrace houses (”<strong>Stavanger</strong> houses”) at Bekkefaret. Photo: Widerøe 1957<br />

Blocks of flats, Misjonsmarka. Photo: Widerøe 1957<br />

The <strong>Stavanger</strong> House received a lot of attention and many<br />

successors throughout the country. Fifty years later, they are<br />

still not old-fashioned. Even though many have been extended,<br />

reflecting increased affluence, many have retained their original<br />

layout and details.<br />

TRACES UNTIL 1965<br />

30

Typical areas with <strong>Stavanger</strong> houses are Steinkopfstykket<br />

and Årrestadstykket near Randabergveien, Tjennsvollskråningen,<br />

Vålandskråningen, Bekkefaret and Saxemarka-<br />

Solsletta. In total, almost 800 houses of this type have<br />

been built.<br />

The <strong>Stavanger</strong> houses from the 1950s stand as a testimony<br />

to the idealism of architects and developers in the difficult<br />

years after the Second World War. Some areas have also<br />

been designated for preservation.<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> is known for its wooden houses. However, other<br />

types of housing have also been built. International trends,<br />

particularly from Sweden, were followed. The first blocks<br />

of flats were built in 1948 and 1951 at Misjonsmarka, with<br />

175 flats in total. Saxemarka was subsequently developed,<br />

with over 400 flats.<br />

Blocks of flats, Saxemarka. Photo: Per Jarle Solheim<br />

Terrace houses (“<strong>Stavanger</strong> houses”) Ullandhaug<br />

One of the basic principles behind the construction of<br />

blocks in the 1950s was that the inhabitants should have<br />

light and fresh air. The blocks were not to be built too close<br />

together. There should be spacious outdoor areas. Every<br />

flat was to have a balcony, to compensate for lack of direct<br />

access to outdoor areas at ground level. The buildings<br />

were simple and economic.

City Expansion in 1965 and<br />

Urban Development Areas<br />

Amalgamation with Madla and parts of Hetland on 1 January<br />

1965 was a watershed in development of the city in more recent<br />

years, providing <strong>Stavanger</strong> with the opportunity for significant<br />

expansion.<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> is not a big city by international standards and does<br />

not have any real suburbs. Instead, so-called development areas<br />

have been established.<br />

The location of the development areas in the expanded <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

municipality was largely defined by the development plan<br />

1966-70. The areas included Hundvåg, Stokka, Tjensvoll-Madlamark,<br />

Kvernevik-Sunde, Kristianlyst-Mariero, Hinna and<br />

Gausel-Godeset-Jattå, all outside the old city boundary, and<br />

Godalen and Rosenli inside it.<br />

Kalhammarviken with Bjelland’s herring meal factory. Photo: Widerøe 1952<br />

Development of Tjensvollskråningen. Photo: Widerøe 1957<br />

The development areas were a natural consequence of<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>’s active building land allocation policy, the socalled<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Model. The <strong>Stavanger</strong> Model entails that the<br />

municipality acquires all larger areas which are designated for<br />

development. The areas are provided with roads, water, sewage<br />

and electricity. Individual areas within the larger areas are then<br />

sold to different developers based on a more detailed development<br />

plan.<br />

Opposite: Madlatorget. Photo: Bitmap<br />

CITY EXPANSION IN 1965 AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

32

Three Typical Development Areas<br />

The following areas are representative of different phases in<br />

development of the city:<br />

Buøy-Hundvåg<br />

Buøy has been part of <strong>Stavanger</strong> since 1878, while Hundvåg<br />

was incorporated into the city in 1965. The water tower at<br />

Buøy, a local landmark, was built in 1920 when the Rosenberg<br />

shipyard moved from Sandvigå at Bjergsted to Buøy.<br />

Houses for the workers were built both on Buøy and also at<br />

Hundvåg. The development of larger housing estates started<br />

in about 1967. At first the pace was fairly slow, but this increased<br />

after construction of the city bridge (Bybrua).<br />

When the bridge was opened, the island’s population was<br />

7 000. There are now 12 500 people living in this area and<br />

the number is expected to increase to 15 000. At the same<br />

time, the drastic reduction of activity at the Rosenberg<br />

shipyard has resulted in increased road traffic due to people<br />

driving to work on the mainland.<br />

The city bridge (Bybrua), constructed by professor Arne Selberg and engineer<br />

Johannes Holt, was opened in December 1977. A cutting connecting<br />

the harbour ring road and the Varmen/Lervig area in 1985 and a tunnel<br />

between the <strong>Stavanger</strong> railway station and the harbour ring road in 1989<br />

greatly improved access to the development areas on Buøy and Hundvåg<br />

Below: Rosenberg shipyard 1921<br />

Planning of a new underwater connection to the mainland<br />

is in progress, both as part of the Ryfast project, connecting<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> to Ryfylke via a 14 km underwater tunnel, and<br />

because an alternative ferry-free connection is desirable.<br />

Opposite: City bridge with Buøy and Hundvåg. Photo: Bitmap<br />

CITY EXPANSION IN 1965 AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

34

Sunde-Kvernevik<br />

When development started almost immediately after expansion<br />

of the city limits in 1965, Sunde and Kvernevik seemed to be<br />

far from town.<br />

Most of Sunde and Kvernevik was developed before 1980.<br />

Given that there were many developers, catering for different<br />

potential buyers, almost all types of houses and building styles<br />

from that period are represented. Developments in society and<br />

increased prosperity after the city’s last recession in the 1960s<br />

are reflected in the number of extensions subsequently built to<br />

the first houses at Kvernevik.<br />

Development area Søra Bråde, Sunde<br />

Building is still going on in the area, and there are examples<br />

of more recent architecture, as illustrated by the photographs<br />

from Søra Bråde at Sunde.<br />

Jåttå-Gauselmarka<br />

A continuous urban belt between <strong>Stavanger</strong> and Sandnes, also<br />

called the “Linear City”, was accepted as one of the basic<br />

principles of development of North Jæren. This made Gausel-<br />

Godeset-Jåttå, midway between Sandnes and <strong>Stavanger</strong> centre,<br />

a prime candidate for development. In addition, the proximity<br />

of work places at Forus made this area very attractive. Local<br />

work places were not part of the concept for any of the development<br />

areas. However, in this case, they were at least located<br />

in the vicinity.<br />

CITY EXPANSION IN 1965 AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

36

Planning started in about 1975. Development of Gauselmarka<br />

started in earnest in about 1980 and continued at<br />

Godeset. Development of Gauselbakken South and North<br />

started in about 2000. A main principle in all cases has<br />

been to ensure easy access to green areas.<br />

The period after 1980 has been a growth period, at the<br />

same time as new architectural fashions have arisen. Godeset-Gauselmarka<br />

and Gauselbakken have been gradually<br />

developed during this period, with a wide range of house<br />

types and styles in both areas. Gauselbakken North is the<br />

last area within the <strong>Stavanger</strong> boundaries where detached<br />

houses have been built to any great extent.<br />

Development will continue northwards at Jåttå.<br />

Development area Gauselbakken North<br />

Left and below: “Building for the future”, Gausel

Industrial Areas and Work Places<br />

In the development areas, there is a predominance of housing<br />

rather than work places. Work places are concentrated today<br />

in two main areas, <strong>Stavanger</strong> centre and Forus, 10 km further<br />

south.<br />

The <strong>Stavanger</strong> municipality’s development plan for 1966-<br />

1970 identified two new industrial areas, Dusavik and Forus.<br />

Both areas have been extremely important for development of<br />

the city.<br />

Dusavik became an onshore base for oil industry activity in<br />

the North Sea. Forus became a regional concentration of work<br />

places which most likely surpasses the visions of the planners<br />

in the 1960s. Jåttåvågen was established later as a construction<br />

site for large North Sea installations, notably the Condeep<br />

concrete gravity platforms.<br />

Early in the 1950s, initiative was taken to develop the Forus<br />

area for industry. Gradually the idea arose of establishing a<br />

large industrial area located centrally between the <strong>Stavanger</strong>,<br />

Sola and Sandnes municipalities as delineated following expansion<br />

of <strong>Stavanger</strong> in 1965. The total area is approximately<br />

65 hectares.<br />

Forus was originally the name of the area where the Stokka<br />

lake, which covered most of Forussletta, discharged into<br />

Forus area. Photo: Bitmap<br />

CITY EXPANSION IN 1965 AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

38

Gandsfjorden. The Stokka lake was drained at the beginning<br />

of the 20th century and the area was cultivated and became<br />

part of the adjacent farms. During the Second World War, the<br />

Germans built a new airport on Forussletta. After the war, the<br />

airport was no longer used, but the State retained ownership<br />

of the airport area.<br />

Forus extends across the boundaries of three municipalities,<br />

but is in reality treated as one continuous industrial area. This<br />

was the basis for the Forus master plan in 1965. The plan<br />

envisaged a traditional industrial area, but this was not to be.<br />

A major change occurred at the end of the 1970s as a result<br />

of oil industry activity. Statoil established its head office at<br />

Forus, followed by other oil companies. Structural changes<br />

Oil-related industry, Forus

in the Norwegian economy, whereby fewer and fewer goods<br />

are produced locally, have also left their mark. Heavy industry<br />

failed to materialize and, instead of manufacturing plants,<br />

warehouses for imported goods were built. The warehouses<br />

also developed gradually into sales outlets and then shops in<br />

competition with businesses in the urban centres.<br />

The area is administered by Forus Næringspark AS, an intermunicipality<br />

company with the mayors of <strong>Stavanger</strong>, Sandnes<br />

and Sola sitting on the board of directors. The company provides<br />

ready-for-building sites for sale to companies - almost<br />

1 000 companies to date.<br />

Today more than 60% of the almost 25 000 work places are<br />

related to offices, services and retail shopping. The number of<br />

work places may double within the next 30 years.<br />

One of the main challenges in the Forus area is the much larger<br />

relative growth in work places compared to other parts of<br />

the greater city area. This has resulted in considerably more<br />

car traffic to and from Forus compared to the town centres and<br />

in strained traffic conditions, particularly in the rush hour.<br />

Plans are now focusing on developing dedicated public transport<br />

routes. Pedestrian and bicycle traffic is also to be facilitated.<br />

The objective is to increase the number of people travelling<br />

to and from work by public transport or on foot or bicycle.<br />

Opposite: Statoil, Forus. Photo: Bitmap<br />

CITY EXPANSION IN 1965 AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

40

Transport and Urban Development<br />

The first car arrived in 1899, 20 years after the railway between<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> and Egersund was opened.<br />

Today approximately 60 000 vehicles are registered in <strong>Stavanger</strong>,<br />

over 75% of which are private cars. This has had enormous<br />

influence on development of the city. As the car became<br />

the most important means of transport, designing the road<br />

network became a major task. Car parking facilities had to be<br />

provided. Increased traffic became a major problem, first in<br />

the city centre and gradually throughout the entire city as new<br />

districts developed and jobs were established outside the<br />

centre. The motorway, which 40 years ago was supposed to<br />

solve transport problems for the foreseeable future, is now<br />

periodically jammed. Rush-hour traffic has become a problem<br />

in large parts of the road network.<br />

Dual-track, Jåttå station<br />

Traffic, Madlaveien at Siddishallen<br />

New roads have been built to remedy the situation. At the same<br />

time, <strong>Stavanger</strong> has focused on reducing the negative impact<br />

of car traffic in the city centre. The first major step has been to<br />

ban cars from parts of the centre at Holmen and Straen. When<br />

the Bergeland tunnel was opened in 1989, the main road past<br />

the cathedral could be restricted to pedestrians. The Storhaug<br />

tunnel reduced through-traffic in the Storhaug area.<br />

In recent years, <strong>Stavanger</strong> has also focused on bicycle traffic as<br />

a safe and effective alternative and on safety for pedestrians.<br />

TRANSPORT AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT<br />

42

However, the number of people opting to cycle has not<br />

increased as much as hoped. Ambitions for increased use<br />

of the bicycle are high and ongoing planning of a main<br />

cycle road between <strong>Stavanger</strong>, Forus and Sandnes is part<br />

of this investment. Planned to be of an exceptionally high<br />

standard, the main cycle road may be the first of its kind in<br />

Norway.<br />

Attention is increasingly focused on public transport, including<br />

establishing bus lanes. The railway between <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

and Sandnes will become dual track in the near future.<br />

Possible excess capacity on this part of the track will be<br />

evaluated for use in a city rail system, initially in the form<br />

of a track from the railway at Gausel via Forus to the<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> airport.<br />

Traffic north to Haugesund and Bergen and east towards<br />

Ryfylke is at present dependent on ferries. Construction of<br />

an Eiganes tunnel has been proposed as part of a satisfactory<br />

route through <strong>Stavanger</strong> for the main coastal road E39<br />

from Kristiansand to Bergen and further north. This solution<br />

could contribute to reducing traffic through housing<br />

areas in <strong>Stavanger</strong>. Continuing north via an underwater<br />

tunnel (Rogfast) between North and South Rogaland, this<br />

will connect the west coast closer, in the same way as<br />

Ryfast (page 34) will connect Ryfylke closer to <strong>Stavanger</strong>.<br />

Bridge for cyclists and pedestrians across Madlaveien<br />

Storhaug tunnel

Glimpses of the New <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Centre<br />

The area considered to be the city centre today is largely the<br />

same as the area within the 1848 town boundary. The district<br />

from the cathedral out to Holmen, limited by the market place,<br />

the cathedral square and Kongsgata, is often described as the<br />

medieval town, with its characteristic narrow and winding<br />

streets. The streets are probably based on old paths and tracks,<br />

adapted naturally to the terrain.<br />

After the Second World War, plans to modernize the city centre<br />

with wide streets and new buildings were considered. The<br />

plans were never implemented and, today, most of Holmen and<br />

the area around the cathedral are reserved for pedestrians.<br />

Kirkegata/Breigata<br />

Skagen with the Fred Hansen house in the foreground<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Cultural Centre<br />

(<strong>Stavanger</strong> Kulturhus Sølvberget)<br />

When walking round this area, one will sooner or later come<br />

across Arneageren. This little square is the natural centre of<br />

the network of streets, and is where the Cultural Centre Sølvberget<br />

is located. Since 1987, Sølvberget has become a central<br />

cultural venue in the city and region and houses the <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

library, <strong>Stavanger</strong> cinema, the Norwegian Children’s Museum<br />

(Norsk Barnemuseum), children’s workshop (Barnas Kulturverksted)<br />

and cafés. The centre is very popular and is always<br />

full of people. It has also developed into an international<br />

arena for work related to freedom of speech, where <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

GLIMPSES OF THE NEW STAVANGER<br />

44

Kirkegata/Prostebakken<br />

Left: Søregata<br />

Below: Arneageren with <strong>Stavanger</strong> Cultural Centre Sølvberget

Freedom Centre, the International Cities of Refuge Network<br />

(ICORN) and the literature and freedom of speech festival<br />

Kapittel have central roles.<br />

The Harbour and Market Place<br />

The harbour has always been important to <strong>Stavanger</strong>. In the<br />

19th century it became a significant international port, but<br />

its shape and function have changed over the years. Major<br />

landfills have created a completely different waterfront, and<br />

the characteristic warehouses, which in the 19th century lay<br />

all along the water’s edge, now lie some distance from the<br />

quayside.<br />

The brig Alpha in Vågen ca 1880<br />

Sightseeing boat Clipper in Vågen in 2007<br />

Goods transport and international ferry traffic have been moved<br />

to Risavika near Tananger. However, local ferry traffic is<br />

still important, and cruise ships are frequent visitors during<br />

the tourist season.<br />

The harbour has become more of a recreational area for festivals<br />

and sporting events than a trade port. A 4 km urban walk,<br />

the “Blue Promenade”, follows the water from Badedammen<br />

to Bjergsted, passing ferry terminals and marinas.<br />

The marketplace, Torget, was important in the day-to-day<br />

life of the town. Farmers and fishermen congregated here and<br />

sold their produce. This traditional marketplace still exists,<br />

although on a smaller scale. It is particularly lively during the<br />

fruit and berry season.<br />

GLIMPSES OF THE NEW STAVANGER<br />

46

Millennium Site, the marketplace (Torget)<br />

Cruise ship Queen Mary 2 in Vågen<br />

Beach volleyball tournament World Tour <strong>Stavanger</strong>

Like the harbour, the marketplace has changed both in shape<br />

and function. Perhaps the most significant change took place<br />

around the start of the new millennium when <strong>Stavanger</strong> selected<br />

Torget as its “Millennium Site” and arranged an open<br />

architectural competition for its development. Millennium<br />

sites were created all over Norway, but the new Torget ranks<br />

amongst the most spectacular. A total renewal of the entire<br />

area, it connects Vågen to the sheltered Breiavatnet lake and<br />

is <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s major open-air arena, accommodating large<br />

events and festivals.<br />

The city centre has changed in use and character. At one time<br />

an important religious centre, it is now a centre for shopping<br />

and recreation. The process of change is illustrated in buildings<br />

from different epochs which have been preserved, rehabilitated<br />

or converted to other uses. These buildings are part<br />

of <strong>Stavanger</strong>’s visual identity, and a challenge to developers.<br />

Some modern buildings, such as the Skagen Brygge Hotel,<br />

have adapted to their historical surroundings; others, like the<br />

Norwegian Petroleum Museum (Oljemuseet) on Kjeringholmen,<br />

are strong contemporary statements.<br />

Skagen Brygge Hotel<br />

The Norwegian<br />

Petroleum Museum<br />

GLIMPSES OF THE NEW STAVANGER<br />

48

Kongsgata<br />

Cathedral square with SR-bank and Norges Bank<br />

Colourful houses in Øvre Holmegate<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Storsenter, Klubbgata

City Centre Plan<br />

Work on a master plan for the centre (Kommunedelplan<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Sentrum 1994 – 2005) started in 1992. When the<br />

plan was approved 4 years later, it was the first comprehensive<br />

master plan for a city centre in Norway.<br />

Combining more than 100 zoning plans, the master plan established<br />

traffic systems as well as parks and green corridors,<br />

conservation projects, “handle with care” buildings and not<br />

least new main projects for the public spaces in the city centre.<br />

Establishment of the plan had been enabled by the opening of<br />

the new E18 (now Rv 509) road from Kannik to Verksalmenningen<br />

in 1989, with a bridge over the railway area and a tunnel<br />

through Storhaug.<br />

Together with the master plan, a local analysis of the city<br />

centre and a City Catalogue were prepared, with 65 proposals<br />

for restoration of smaller public spaces. Some of the projects<br />

GLIMPSES OF THE NEW STAVANGER<br />

50

could be combined and created the basis for an action plan<br />

with five main proposed projects: the Central Public Space<br />

(development of Torget and the area round Breiavatnet), the<br />

Blue Promenade, the “green” Løkkeveien street, the “Green<br />

Corridor” between Breiavatnet and Mosvatnet, and <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

East (upgrading of the Nedre Blåsenborg and Smedgate<br />

areas). The projects, shown on the map below, were completed<br />

or under construction in 2008.<br />

Main projects, City Centre Plan<br />

Blocks of flats in the centre<br />

Previous page, bottom left: St. Olav seen from Breiavatnet. Previous page:<br />

Olav V’s gate. Above: Badedammen. Below: Blåsenborg

Green Areas in <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

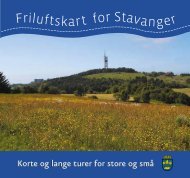

<strong>Stavanger</strong> has perhaps the best continuous urban green structure<br />

of all Norwegian cities.<br />

Everything can be found here: parks, woods, beaches, lakes,<br />

meadows with wild flowers, viewpoints, skating facilities,<br />

playgrounds, cycling paths, bridle paths, ball parks, outdoor activity<br />

centres, swimming facilities and sports halls, connected<br />

together and make accessible by a network of footpaths. When<br />

the network is complete, it will offer approximately 220 km of<br />

“green” connections.<br />

In addition, many of the smaller islands in the municipality are<br />

designated for outdoor life and nature conservation.<br />

Green areas Above: Lundsneset Below: Mosvatnet Right: Bathing at Godalen<br />

The foundation for this continuous green structure was laid<br />

in the first master plan for the <strong>Stavanger</strong> municipality in the<br />

late 1960s. This was followed up in a Green Plan, approved in<br />

1992, and in all subsequent master plan revisions.<br />

During the last five years, the municipality has put great effort<br />

into securing outdoor areas for the general public through the<br />

public outdoor recreation area project (Friområdeprosjektet).<br />

The project is still ongoing and every year major investments<br />

are made to secure and make accessible more green areas.<br />

You will always find a footpath in the vicinity!<br />

GREEN AREAS IN STAVANGER<br />

52

Grønnstruktur<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> har kan hende den aller beste urbane, sammenhengende<br />

grønnstrukturen av alle norske byer.<br />

Her er alt: Parker, skoger, strender, vann og innsjøer, blomsterenger,<br />

utsiktspunkter, naturvernområder, kulturlandskaper,<br />

skateanlegg, lekeplasser, sykkelstier, ridestier, balløkker,<br />

friluftssentre, badeplasser, tett kontakt med idrettsanlegg og<br />

skolegårder, bundet sammen og gjort tilgjengelig med turveinettet,<br />

som ferdig utbygd vil by på ca 220 km sammenhengende<br />

grønne forbindelser.<br />

I tillegg er mange av de mindre øyene i <strong>kommune</strong>n sikret for<br />

friluftsliv og naturvern.<br />

Grunnlaget for denne gode, sammenhengende grønne strukturen,<br />

ble lagt allerede i <strong>Stavanger</strong>s første generalplan fra slutten<br />

av 60-årene, fulgt opp gjennom Grønn Plan og alle senere<br />

utgaver av <strong>kommune</strong>plan for <strong>Stavanger</strong>. De 5 siste årene har<br />

<strong>kommune</strong>n lagt ekstra stor innsats i å sikre og tilrettelegge friarealene<br />

for allmenn bruk, gjennom Friluftsprosjektet hvor det<br />

årlig investeres store beløp i sikring og tilgjengeliggjøring av de<br />

grønne områdene.<br />

Du finner alltid en turvei i nærheten!

Two Major Town Planning Competitions<br />

Several town planning competitions have been held in <strong>Stavanger</strong>,<br />

both for the central areas and also for the new districts.<br />

Two examples of the latter, which have subsequently been<br />

implemented, are Tjensvollbyen, started in 1968, and Jåttåvågen,<br />

started 32 years later.<br />

Tjensvollbyen (“Tjensvoll Town”)<br />

The concept of Tjensvollbyen had already arisen before amalgamation<br />

of the municipalities in 1965. The approximately 60<br />

hectare area lies partially within the old Madla and <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

municipalities, on what was mostly open agricultural land.<br />

The idea was to build houses and a centre with shops and services<br />

for the inhabitants in the middle of the area. Other work<br />

places were not included in the concept.<br />

The planning competition in 1968 was won by the planning<br />

office of Andersson og Skjånes AS together with architectural<br />

firm Alex Christiansen AS. These formed the Tjensvoll team,<br />

which handled detailed planning. A smaller part of the area,<br />

Haugtussa, was awarded to the second prize winner, Brantenberg,<br />

Brantenberg and Hiorthøy, as an experimental area for<br />

low-cost housing.<br />

The development plan was ready in 1969. An independent<br />

committee was established to process planning issues within<br />

the area. Building started in 1972. Altogether approximately<br />

TWO MAJOR TOWN PLANNING COMPETITIONS<br />

54

2 000 houses were built, mostly under the direction of the <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

and Hetland Cooperative Building and Housing Associations.<br />

By 1980, most of Tjensvoll had been developed.<br />

One of the distinctive features of Tjensvollbyen is the large variety<br />

of house types (low blocks, terrace houses and detached<br />

houses) and sizes (from 1 to 4 bedrooms). However, the impression<br />

is harmonious, not least because one firm of architects<br />

had overall responsibility for the main part of the development.<br />

The social profile of the area is another special feature. The<br />

almost 2 000 housing units include no “luxury apartments”.<br />

Tjensvollbyen was also the first large area in <strong>Stavanger</strong> which<br />

was designed to be free of cars. The majority of the car parking<br />

spaces were placed under the blocks of flats which surround<br />

the rest of the houses. Unfortunately, new driving and shopping<br />

habits have resulted in the commercial centre, which at<br />

the time was thought to be ideally located in the middle of the<br />

area, being used much less than anticipated.<br />

Left: Tjensvoll and <strong>Stavanger</strong> Forum Below: Individual houses, Tjensvoll

Jåttåvågen (“Jåttå Bay”)<br />

Jåttåvågen is located approximately 7.5 km from <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

centre and approximately 3–5 km from the industrial area at<br />

Forus. The area is situated alongside the public transport route<br />

between <strong>Stavanger</strong> and Sandnes, where dual-track railway line<br />

is being constructed.<br />

During the most hectic North Sea development period, Jåttåvågen<br />

became a construction site for concrete structures. The<br />

first structure to be built was the Ekofisk tank in 1971-1973,<br />

followed by 14 Condeep platforms. The last of these was the<br />

Troll platform in 1995. One of the tallest structures in the<br />

world, it also marked the end of Jåttåvågen’s period as construction<br />

site for the North Sea.<br />

In 1998, the <strong>Stavanger</strong> municipality decided that Jåttåvågen<br />

should become a new urban district, with houses, industry<br />

and services, and that the municipality and private developers<br />

Hinna Park AS should cooperate in developing the area.<br />

Large parts of the bay had been filled in as part of the construction<br />

site and there was little nature or agriculture to take<br />

into account. However, one landmark of Jåttåvågen’s significance<br />

for North Sea oil industry has been preserved. The<br />

“leaning tower”, which was originally built to test concretelaying<br />

techniques, still stands.<br />

In 2000, the municipality arranged an open Nordic town planning<br />

competition which was to provide the basis for a local<br />

TWO MAJOR TOWN PLANNING COMPETITIONS<br />

56

master plan. Jåttåvågen was to be developed as:<br />

- A modern area for high technological and internationally<br />

orientated businesses (5 000 – 8 000 work places)<br />

- A futuristic and attractive housing area (min. 1 500 houses)<br />

- A pilot project for high density and ecofriendly development<br />

- A recreational area by the sea and a valuable link in<br />

continuous green areas<br />

- An area of high architectural quality, a meeting place for<br />

the district and a dynamo for the region.<br />

The winners of the competition were engaged to prepare the<br />

master plan, with Lund Hagem as main consultant and Team<br />

Yoto–70 grader nord, as contributor.<br />

The “leaning tower” will be an important element in the main<br />

axis between Jåttånuten and the Ryfylke mountains. A central<br />

public space will have room for large events.<br />

Jåttåvågen Previous page: Hinna Park block with the leaning tower in<br />

the background Above: Terrace houses Below: Tower blocks under<br />

construction<br />

A new stadium for the Viking football club and a district commercial<br />

centre were built early on. These have been important<br />

generators for development of the area. This, together with the<br />

deliberate focus on public transport with a new railway station<br />

on the dual-track railway, distinguishes Jåttåvågen from Tjensvoll.<br />

The size and type of dwellings is varied, as at Tjensvoll,<br />

but with no detached houses and a large proportion of flats in<br />

tower blocks.

The first home match at the Viking stadium was played in<br />

May 2004. A year later, the commercial centre opened, with<br />

10 000 m² of businesses and services. By the end of 2007,<br />

approximately 600 dwellings and 40 000 m² businesses, with<br />

1 500 work places, had been built or were under construction.<br />

A new secondary school was also opened in 2008 in the same<br />

area.<br />

Jåttåvågen will be an urban entity halfway between the established<br />

centres in <strong>Stavanger</strong> and Sandnes, with more than<br />

2 000 dwellings (about the same as at Tjensvoll), but with approximately<br />

7 000 work places and a number of services for<br />

the inhabitants and visitors.<br />

Jåttå secondary school<br />

Hinna Park housing complex<br />

Below: Housing at Jåttåvågen. Opposite: Overview of Jåttåvågen with Viking stadium<br />

and Jåttåvågen secondary school. Photo: Bitmap<br />

TWO MAJOR TOWN PLANNING COMPETITIONS<br />

58

Two Major Central Development Areas<br />

Until 2000, the trend was for the majority of the population<br />

to move out of the city centre, initially to the areas close to<br />

the centre, Storhaug, Våland, Vestre Platå and Kampen, and<br />

later to the new development areas.<br />

Recently, this trend has reversed to a certain extent and larger<br />

housing projects have been built and continue to be built<br />

within the town boundary of 1848. This applies particularly<br />

to areas where traditional industry was located until the end<br />

of the canning era in the 1960s and the establishment of<br />

Forus as the new inter-municipality business district.<br />

Urban Seafront (<strong>Stavanger</strong> East)<br />

In the 1950s, the eastern part of town, together with Hillevåg,<br />

had the largest concentration of industry in <strong>Stavanger</strong>.<br />

Twenty years later, many of the companies had disappeared<br />

or moved. There was a surplus of empty sites, particularly<br />

along the waterfront where the canning factories had been<br />

located. The reduction in employment and the increased<br />

number of empty industrial buildings resulted in the increasingly<br />

dilapidated character of the area.<br />

In 1999, Urban Seafront (Urban Sjøfront) was introduced<br />

as a new concept for the eastern part of town. Prior to this,<br />

plans were to continue using the area as a business district<br />

with a large element of industrial activity. The Urban Seafront<br />

concept proposed transforming the area into a mix<br />

TWO MAJOR CENTRAL DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

60

of housing, work places, recreation and culture. Many were<br />

enthusiastic about the concept and contributed to working towards<br />

its implementation. This work has been largely pursued<br />

Left: Urban Seafront concept Below: Tou Scene<br />

by Urban Sjøfront AS, a non-profit company owned by several<br />

landowners in the area.<br />

Many elements of the concept from 1999, such as a public<br />

promenade along the waterfront and different types of activity<br />

zones extending in from the sea, have been included in<br />

subsequent plans and projects. Development of the so-called<br />

“cultural axis” along Kvitsøygata has progressed furthest. The<br />

most important of the zones is undoubtedly centred around<br />

Tou Scene, an alternative cultural stage established in the old<br />

premises of the Tou Brewery.<br />

A zoning plan from 2002 for the southern part of the area stipulates<br />

a maximum height of 4-5 floors for buildings in most

of the district. A similar plan for the northern part of the area<br />

was approved in 2006. Both plans allow for both housing<br />

and commercial activity.<br />

So far, a series of high density housing projects has been<br />

completed at the Urban Seafront. Few commercial buildings<br />

have been constructed.<br />

Two major international architectural competitions have<br />

been held for development of parts of this<br />

area. The district on the north side of<br />

Lervig was one of several European<br />

sites included in the international<br />

architectural competition Europan<br />

8. An international<br />

architectural competition<br />

was also held for the area<br />

at the outside edge of<br />

Siriskjær as part of<br />

the Norwegian Wood<br />

project (see page 78).<br />

Badedammen is the<br />

part of Urban Seafront<br />

which has progressed<br />

furthest. The Strømsteinen<br />

area had long been used<br />

Above: Décor from Badedammen block Right. Overview of Badedammen<br />

TWO MAJOR CENTRAL DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

62

as a lido by the townspeople after several inhabited small<br />

islands were connected together in the 19th century and the<br />

seawater lake Badedammen was established. At about the<br />

same time, houses were built in the area in addition to the<br />

wharf warehouses which already existed.<br />

During the course of the next century, landfills were carried<br />

out in the area, particularly in Banevigå in the west, and<br />

many of the warehouses were replaced by larger industrial<br />

buildings.<br />

When the bridge to the islands was constructed in 1978, one<br />

of its columns was located in Badedammen. Ten years later<br />

a development plan for the Badedammen area was approved.<br />

The plan allowed development of both private housing and<br />

commercial buildings. Canals were to be dug into Badedammen<br />

to recreate the impression of an area of several small islands.<br />

However, development of the area came to a standstill<br />

due to economic stagnation.<br />

Only a few years later economic conditions changed. From<br />

the mid 1990s, new buildings have been constructed along<br />

almost the entire seafront. On the whole, these have been<br />

planned individually and have followed the development<br />

plan of 1988 to a limited extent only.<br />

The Badedammen park is located at the south-easternmost<br />

end of the Blue Promenade and is now being upgraded.<br />

Badedammen with city bridge

Bjergsted Area<br />

The area between the Bjergsted park and “Old <strong>Stavanger</strong>” has<br />

been totally transformed over the last 15 years. Prior to this,<br />

the area was an industrial zone. The gasworks, with two large<br />

gasometers, were located here as well as a nail factory, coal<br />

storage, print shop, soap factory and canning factories. These<br />

activities have now been either discontinued or moved. In their<br />

place, urban flats have been built or are under construction, in<br />

addition to a few office premises.<br />

The first project was Bjergsted Terrasse in about 1990.<br />

Straen Terrasse, just north of “Old <strong>Stavanger</strong>”, in 2000 was<br />

first in a new wave of large-scale developments in the area.<br />

The newest project, which is now under construction, Løkkeveien<br />

111, will create a clear boundary for Old <strong>Stavanger</strong><br />

towards the west.<br />

Photo montage Løkkeveien 111<br />

Above: New blocks of flats, Bjergsted Opposite: Overview of Bjergsted.<br />

Photo: Bitmap<br />

The same area. Gasworks 1930s. Photo: Wilse<br />

TWO MAJOR CENTRAL DEVELOPMENT AREAS<br />

64

Culture is Urban Development<br />

After the Second World War, cultural politics were an important<br />

part of establishment of the welfare state. At the same<br />

time, the definition of culture was expanded to include a wide<br />

range of human activities. A cultural democracy was to be<br />

created, where the government was to play an major role.<br />

In 1964 <strong>Stavanger</strong> established a Standing Committee of Cultural<br />

Affairs, followed in 1969 by the first culture plan. With its<br />

focus on the new and broader vision of culture, this plan was<br />

groundbreaking.<br />

Today, the <strong>Stavanger</strong> municipality conducts an active and<br />

broad cultural policy to ensure that cultural values are accessible<br />

to more people and to include and support new and<br />

untraditional cultural activities. A new plan for art and culture<br />

2009–2014 will establish the main guidelines for future cultural<br />

policy.<br />

Here are some examples of the city’s varied and exciting cultural<br />

life:<br />

Rogaland Theatre<br />

In 1850, the mayor L.W. Hansen built a new building at Skagen<br />

which was furnished with theatre facilities on the first<br />

floor and space for 300 spectators. Performances were later<br />

held in <strong>Stavanger</strong> Sparekasse’s assembly hall, and in 1883 the<br />

curtain went up for the first time at a new theatre building at<br />

From the opening of European City of Culture 2008<br />

CULTURE IS URBAN DEVELOPMENT<br />

66

Main stage, Rogaland Theatre. Performance of “The Thousandth Heart” 2007. Photo: E. Ashley

Kannik. The Rogaland Theatre, which was formally established<br />

in 1947, is housed in this building today. The theatre has<br />

been expanded several times. It has also taken over the adjacent<br />

old gymnastics hall, which has been rebuilt and used for<br />

children’s and youth theatre since 1957. Today the Rogaland<br />

Theatre is one of the leading theatres in the country and presents<br />

10–14 productions each year on four different stages.<br />

Sølvberget: <strong>Stavanger</strong> Kulturhus is described on page 44.<br />

Museums and Collections<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> has almost 20 museums which take care of and<br />

promote the cultural heritage of the city and region. These<br />

cover the whole spectrum from large to small collections.<br />

The <strong>Stavanger</strong> Museum has two departments at Muségata<br />

16. The Zoological Department displays bird<br />

life, with main emphasis on Rogaland, as well as<br />

Norwegian and foreign mammals. The Department<br />

of Cultural History has a special responsibility<br />

for documenting the general<br />

cultural history of Rogaland, with<br />

main emphasis on the history of<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong>. The museum also administers<br />

the Norwegian Children’s<br />

Museum, the Medical Museum (Medisinsk<br />

Museum) and the Norwegian Museum<br />

of Printing (Norsk Grafisk Museum).<br />

<strong>Stavanger</strong> Museum. Above: 18th century interior<br />

Left: Finback whale scull and sparrowhawk<br />

CULTURE IS URBAN DEVELOPMENT<br />

68

The Maritime Museum (Sjøfartsmuseet), a special museum<br />

for the maritime history of the south-west of Norway,<br />

is located at Nedre Strandgate 17 and 19. The Canning<br />

Museum (Hermetikkmuseet) is located in a former canning<br />

factory at Øvre Strandgata 88 in Old <strong>Stavanger</strong>.<br />

The Museum of Archaeology (Arkeologisk museum i <strong>Stavanger</strong>),<br />

in Peder Klows gate 30, covers the history of Rogaland<br />

from the appearance of the first humans until the end<br />

of the Middle Ages. In addition to exhibitions, the museum<br />

does extensive research. In the summer months, a number<br />

of archaeological digs are carried out under the museum’s<br />

direction.<br />

Above: Archeological Museum. Below: Norwegian Petroleum Museum.<br />

Bottom: Rogaland Museum of Fine Arts<br />

The Norwegian Petroleum Museum (Norsk Oljemuseum)<br />

at Kjeringholmen is a modern and interactive museum. The<br />

museum shows how oil and gas are created and the technological<br />

development which enables these resources to be<br />

used.<br />

The Rogaland Museum of Fine Arts (Rogaland Kunstmuseum)<br />

is situated in a beautiful location at Mosvannsparken,<br />