Estimating Distributions of Counterfactuals with an Application ... - UCL

Estimating Distributions of Counterfactuals with an Application ... - UCL

Estimating Distributions of Counterfactuals with an Application ... - UCL

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

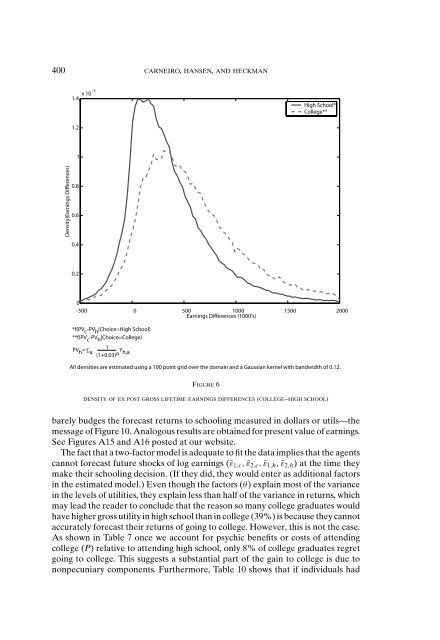

400 CARNEIRO, HANSEN, AND HECKMAN<br />

1.4 x10-3<br />

High School*<br />

College**<br />

1.2<br />

1<br />

Density(Earnings Differences)<br />

0.8<br />

0.6<br />

0.4<br />

0.2<br />

0<br />

-500 0 500 1000 1500 2000<br />

Earnings Differences (1000's)<br />

*f(PV c -PV h |Choice=High School)<br />

**f(PV c -PV h |Choice=College)<br />

PV<br />

1<br />

h = Σ a (1+0.03) a Y h,a<br />

All densities are estimated using a 100 point grid over the domain <strong>an</strong>d a Gaussi<strong>an</strong> kernel <strong>with</strong> b<strong>an</strong>dwidth <strong>of</strong> 0.12.<br />

FIGURE 6<br />

DENSITY OF EX POST GROSS LIFETIME EARNINGS DIFFERENCES (COLLEGE–HIGH SCHOOL)<br />

barely budges the forecast returns to schooling measured in dollars or utils—the<br />

message <strong>of</strong> Figure 10. Analogous results are obtained for present value <strong>of</strong> earnings.<br />

See Figures A15 <strong>an</strong>d A16 posted at our website.<br />

The fact that a two-factor model is adequate to fit the data implies that the agents<br />

c<strong>an</strong>not forecast future shocks <strong>of</strong> log earnings (¯ε 1,c , ¯ε 2,c , ¯ε 1,h , ¯ε 2,h ) at the time they<br />

make their schooling decision. (If they did, they would enter as additional factors<br />

in the estimated model.) Even though the factors (θ) explain most <strong>of</strong> the vari<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

in the levels <strong>of</strong> utilities, they explain less th<strong>an</strong> half <strong>of</strong> the vari<strong>an</strong>ce in returns, which<br />

may lead the reader to conclude that the reason so m<strong>an</strong>y college graduates would<br />

have higher gross utility in high school th<strong>an</strong> in college (39%) is because they c<strong>an</strong>not<br />

accurately forecast their returns <strong>of</strong> going to college. However, this is not the case.<br />

As shown in Table 7 once we account for psychic benefits or costs <strong>of</strong> attending<br />

college (P) relative to attending high school, only 8% <strong>of</strong> college graduates regret<br />

going to college. This suggests a subst<strong>an</strong>tial part <strong>of</strong> the gain to college is due to<br />

nonpecuniary components. Furthermore, Table 10 shows that if individuals had