Dutch Disease, Resource Curse and Development*

Dutch Disease, Resource Curse and Development*

Dutch Disease, Resource Curse and Development*

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

*based on Teaching Material on “<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>, <strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Development”, UNCTAD, Virtual Institute, Geneva 2011<br />

<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>, <strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Development*</strong><br />

Jan Priewe, professor of economics at HTW Berlin – University of<br />

Applied Sciences

Outline<br />

1) Introduction<br />

2) What are the Issues<br />

3) St<strong>and</strong>ard Theories<br />

4) Debates on St<strong>and</strong>ard Theories<br />

5) Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC<br />

6) Coping with DD <strong>and</strong> RC : Policy Strategies<br />

7) Conclusions<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

2

1. Introduction<br />

• <strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> (DD): discovery of new natural<br />

resources or a price boom leads to real appreciation<br />

of the currency <strong>and</strong> hampers growth of<br />

manufacturing or other tradable sectors<br />

• <strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong> (RC): long-lasting negative effect<br />

stemming from DD <strong>and</strong> its negative consequences:<br />

technical progress is subdued -> negative<br />

consequences on manufacturing<br />

• ample empirical evidence: most resource-rich<br />

countries grew less than resource-poor countries,<br />

over the long run; but great diversity between<br />

countries; few positive models<br />

• Institutions/governance/policies: can “strong”<br />

institutions <strong>and</strong> “good governance” or prudent<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

3

2. What are the Issues<br />

• the “Economist” (26 November, 1977: 82-83) first coined<br />

the natural gas boom in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s in the 1970s as<br />

a “<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>”<br />

• This boom had caused a real appreciation which<br />

dampened manufactured exports <strong>and</strong> GDP growth. The<br />

new boom sector crowded out export-oriented industries.<br />

• Adam Smith (<strong>and</strong> others) had suspected that rentier<br />

economies, based on mineral resources rather than manmade<br />

goods cannot generate the wealth that capitalist<br />

nations are capable to produce<br />

• Many of the oil-rich countries experienced unambiguously<br />

less growth over many decades, despite occasionally<br />

mushrooming oil prices, than other developing or OECD<br />

countries.<br />

• DD in the long run: natural resource curse (RC) rather<br />

than a blessing, since technical progress, linked to<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

4

Focus on Institutions <strong>and</strong> “Good<br />

Governance”<br />

• Botswana, Norway <strong>and</strong> Indonesia are often<br />

considered as positive models, but a closer look<br />

shows that hey are rather special cases<br />

• empirical evidence pro or contra seems to be<br />

enigmatic<br />

• recently the initial focus on exchange rates was<br />

widened or even replaced towards “good<br />

governance” <strong>and</strong> “policies”<br />

• recently many natural resources have been<br />

discovered mainly in Africa <strong>and</strong> Latin America<br />

• if it were mainly a matter of institution building <strong>and</strong><br />

application of proper policies, Africa might face a<br />

bright future <strong>and</strong> it is high time to discover blueprints 5<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

3. STANDARD THEORIES<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

6

<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>: The St<strong>and</strong>ard Model I<br />

• static model of <strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> by Corden/Neary (1982)<br />

• Three representative commodities: traditional<br />

tradables, especially manufactured goods (M), nontradable<br />

sector, primarily services (S), boom sector (E),<br />

e.g. fossil energy; note: agricultural goods are in principle<br />

also tradables<br />

• Assumtpions I: small open economy: the world market<br />

prices for tradables <strong>and</strong> natural resources are given: real<br />

exchange rate = Y S /Y M (Y is output)<br />

• Assumptions II: (1) full employment (2) no spending for<br />

capital accumulation (3) international capital immobility so<br />

that saving of windfalls abroad is excluded (4) hence<br />

capital account <strong>and</strong> current account are in balance (5)<br />

inflation is excluded (only a one-time price increase in<br />

non-tradables) (6) no money (Barter economy) <strong>and</strong> no<br />

nominal exchange rate, hence no monetary <strong>and</strong><br />

exchange rate policy (7) no interest rate (8) no<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

7

<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>: The St<strong>and</strong>ard Model II<br />

Figure 1: Effect of the boom on the<br />

labour market<br />

Source: Corden/Neary<br />

(1982: 828).<br />

Before the boom: total labour<br />

supply O s -O t ; wage is w 0 ;<br />

L T <strong>and</strong> L S are labour<br />

dem<strong>and</strong> for tradables <strong>and</strong><br />

non-tradables; equilibrium<br />

in A<br />

Effects of resource boom:<br />

1) resource movement effect:<br />

• direct deindustrialisation A<br />

→ B<br />

• labour dem<strong>and</strong> in the boom<br />

sector crowds out<br />

employment in other<br />

sectors; L T shifts to L‟ T<br />

2) spending effect B → G<br />

Indirect deindustrialisation:<br />

• more revenue → additional<br />

8<br />

spending <strong>and</strong> labour<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>: The St<strong>and</strong>ard Model III<br />

Figure 2: Effects of the boom on<br />

the commodity market<br />

Source: Corden/Neary (1982:<br />

829)<br />

Fig. 2 shows a productionpossibility-frontier-curve:<br />

• initially, before the boom, curve<br />

T-S. The highest indifference<br />

curve can be reached at a. The<br />

tangent at a is the real<br />

exchange rate.<br />

• The resource boom shifts the<br />

curve to T„-S.<br />

• If there were no exchange rate<br />

change, b would be the new<br />

equilibrium.<br />

• But following the traditional<br />

consumption pattern O-n, point<br />

c would be reached, i.e. much<br />

more spending for S.<br />

9<br />

• Since non-tradables have<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

<strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>: The St<strong>and</strong>ard Model IV<br />

• St<strong>and</strong>ard Model does not assert that resource boom<br />

makes country poor – but real appreciation occurs <br />

more imports of tradables crowding out of<br />

domestic tradables (manfactures <strong>and</strong>/or agricultural<br />

goods) enhanced production of non-tradables<br />

• Does not look at resource price drops or exhaustion<br />

of resources<br />

• If resource movement effect is small (extraction of<br />

natural resources is capital intensive), spending<br />

effect predominates<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

10

<strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong> I<br />

• Sachs/Warner (1995) : empirical research, <strong>and</strong><br />

drawing on endogenous growth theory<br />

• evidence from cross country studies shows that<br />

natural resource-rich countries have experienced<br />

less long-term growth rates than resource poor<br />

countries<br />

• the price level in “rentier economies” (big share of<br />

income are resource rents) is in general higher than<br />

in resource poor economies<br />

• resource-rich countries suffered from lower growth of<br />

manufacture exports<br />

• Manufacturing is main carrier of technical progress<br />

(human capital, R & D) 11<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

<strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong> II<br />

• higher domestic prices lead to reduced<br />

competitiveness of manufacturing<br />

• Engines for growth: Learning-by-doing effects, spilling<br />

over to other firms <strong>and</strong> industries, <strong>and</strong> increasing<br />

returns to scale<br />

• even if DD effect is only temporary, temporarily<br />

reduced knowledge accumulation can have a lasting<br />

effect (path dependence). From this angle, it is<br />

predominantly reduced human capital accumulation<br />

that hampers industrialization, continuous upgrading<br />

<strong>and</strong> diversification of industries.<br />

• high volatility of mineral <strong>and</strong> energy commodities <strong>and</strong><br />

related uncertainties, 12<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

<strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong> III<br />

Figure 3: Growth <strong>and</strong> natural resource abundance 1970-1989<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

13

<strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong> IV<br />

Figure 4: Natural resource dependence <strong>and</strong> exports of manufactures (1970-89)<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

14

4. DEBATES ON STANDARD<br />

THEORIES: LIMITATIONS,<br />

SHORTCOMINGS, CRITICISMS<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

15

Limitations, Shortcomings, Criticisms: DD<br />

• Although st<strong>and</strong>ard model captures correctly the key problem<br />

of resource booms, it suffers from too strong assumptions<br />

which obfuscate reality<br />

• To use the model for empirical analysis, money <strong>and</strong><br />

currencies must be included<br />

• Transposing the basic features of the model from a barter<br />

economy to a monetary economy opens the perspective to<br />

mitigate or cure the disease with macroeconomic, especially<br />

exchange rate policy<br />

• Inflation, monetary <strong>and</strong> exchange rate policy should be<br />

included<br />

• … <strong>and</strong> also international capital mobility incl. saving the<br />

windfalls abroad<br />

• DD <strong>and</strong> RC can be understood in a Ricardian perspective:<br />

natural resources become new comparative advantage that<br />

crowds out other traditional sectors<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

16

Limitations, Shortcomings, Criticisms: RC<br />

• Windfall boom phases can increase the wealth of<br />

resource-rich countries considerably – booms don‟t look<br />

like disease or a curse … but development of<br />

employment <strong>and</strong> man-made wealth outside the boom<br />

sector is indeed hindered<br />

• Strong inflation due to spending effect is biggest risk<br />

which is not reflected in st<strong>and</strong>ard model<br />

• Other deficiency of the model: income distribution not<br />

addressed; rentier economies are mostly not “normal”<br />

market economies – strong financial role of state which<br />

receives big parts of the rents<br />

• The long-run disease is difficult to diagnose with regard<br />

to the initial causes <strong>and</strong> the subsequent additional<br />

causes that eventually lead to vicious circles which<br />

corroborate the disease.<br />

• Governments <strong>and</strong> central banks often try to mitigate too<br />

strong appreciations or depreciations - the more<br />

successful the attenuation is, the less visible is the<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

17

5. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FOR DD<br />

AND RC<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

18

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC I<br />

Figure 5: Crude oil prices 1970-2009<br />

Source : http ://www.wtrg.com/oil_graphs/oilprice1947.gif<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

19

index metals & minerals, 1970=100<br />

US$/barrel, crude oil (Brent)<br />

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC II<br />

Figure 6: Prices of mineral commodities <strong>and</strong> crude oil<br />

Prices of mineral commodities* (index, 1970=100) <strong>and</strong> crude oil<br />

(US$/barrel), 1982-2010<br />

800<br />

700<br />

160<br />

140<br />

600<br />

120<br />

500<br />

100<br />

400<br />

80<br />

300<br />

60<br />

200<br />

40<br />

100<br />

20<br />

0<br />

0<br />

Q2 1982<br />

Q4 1983<br />

Q2 1985<br />

Q4 1986<br />

Q2 1988<br />

Q4 1989<br />

Q2 1991<br />

Q4 1992<br />

Q2 1994<br />

Q4 1995<br />

Q2 1997<br />

Q4 1998<br />

Q2 2000<br />

Q4 2001<br />

Q2 2003<br />

Q4 2004<br />

Q2 2006<br />

Q4 2007<br />

Q2 2009<br />

index metals & minerals, lhs<br />

crude oil, brent, US$/barrel, rhs<br />

*Gold, silver, aluminum, zinc, copper, potash, lead, iron<br />

Source: Datastream, own calculations<br />

20<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

Empirical evidence III<br />

• Oil boom in the 1970s was followed by a long slump<br />

until end of 1990s, but often appreciation of REER was<br />

not offset by subsequent depreciation<br />

• In some countries spending windfalls led to high<br />

inflation which triggered depreciation of the exchange<br />

rate<br />

• During the oil boom 1998-2007 most countries<br />

experienced real appreciation - or avoided this through<br />

saving windfalls abroad (central bank reserves,<br />

sovereign wealth funds etc.)<br />

• In contrast to st<strong>and</strong>ard model, model countries built up<br />

big current account surpluses during booms mirror<br />

image of saving windfalls abroad<br />

• Low long-term growth in oil-rich countries, but wealth<br />

21<br />

accumulation abroad in several countries<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

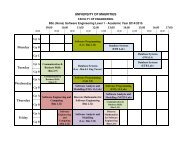

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC IV<br />

Algeria 1960-2010 1.10 1998-2010 1.99<br />

Table 1:<br />

GDP growth<br />

rate per<br />

capita p.a. in<br />

OPEC<br />

countries,<br />

per cent<br />

Angola 1985-2010 2.29 1998-2010 6.59<br />

Ecuador 1960-2010 0.70 1998-2010 2.29<br />

Iran, Islamic Rep. (1965-2009) 1965-2009 0.88 1998-2009 3.23<br />

Iraq 1997-2010 0.32 1998-2010 -1.87<br />

Libya 1999-2009 2.11 1999-2009 2.11<br />

Kuwait 1995-2007 1.60 1998-2008 2.45<br />

Nigeria 1960-2010 1.29 1998-2010 3.38<br />

Qatar 2000-2009 3.27 2000-2009 3.27<br />

Saudi Arabia 1968-2009 0.84 1998-2009 0.64<br />

United Arab Emirates 1973-2009 -1.80 1998-2009 1.24<br />

Venezuela, RB 1960-2010 0.00 1998-2010 0.49<br />

OPEC average* 1.05 2.15<br />

OECD-countries 1970-2010 2.01 1998-2010 1.24<br />

sub-Sahara Africa (developing only) 1960-2010 0.76 1998-2010 1.82<br />

South Asia 1960-2010 3.20 1998-2010 5.19<br />

Least developed countries 1981-2010 1.48 1998-2010 3.43<br />

Latin America & Caribbean (developing only) 1960-2010 1.71 1998-2010 1.84<br />

East Asia & Pacific (developing only) 1960-2010 5.52 1998-2010 7.81<br />

*per annum in the periods indicated<br />

Source: World Bank, WDI, own calculations<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

22

% of GDP<br />

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC V<br />

Figure 7: Total Natural <strong>Resource</strong> Rents<br />

Total natural resource rents* in % of GDP<br />

Algeria<br />

120<br />

Angola<br />

100<br />

peak of average<br />

resource rent of 19<br />

countries 2005: 48%<br />

Iraq<br />

Azerbaijan<br />

Bolivia<br />

Ecuador<br />

80<br />

Iraq<br />

Kuwait<br />

60<br />

40<br />

Angola<br />

Nigeria<br />

Libya<br />

Norway<br />

Russian Federation<br />

Saudi Arabia<br />

United Arab Emirates<br />

20<br />

Venezuela, RB<br />

Indonesia<br />

0<br />

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008<br />

Source: WB, WDI 2011<br />

Norway<br />

*sum of oil rents, natural gas rents, coal rents (hard <strong>and</strong> soft), mineral rents, <strong>and</strong> forest rents<br />

Mexico<br />

Nigeria<br />

OECD members<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

23

% of GDP<br />

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC VI<br />

Figure 8: Manufacturing, value added, % of GDP<br />

Manufacturing, value added, % of GDP<br />

Angola<br />

35<br />

Algeria<br />

Venezuela, RB<br />

30<br />

Indonesia<br />

Ecuador<br />

Russian Federation<br />

25<br />

average China,<br />

India, Brazil<br />

Azerbaijan<br />

Saudi Arabia<br />

20<br />

Venezuela<br />

Russian Federation<br />

Kuwait<br />

15<br />

Libya<br />

Bolivia<br />

10<br />

Norway<br />

Iraq<br />

5<br />

0<br />

1990<br />

1991<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

Iraq<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

Nigeria<br />

2005<br />

2006<br />

2007<br />

2008<br />

2009<br />

Angola<br />

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, own calculations<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

Norway<br />

Indonesia<br />

United Arab Emirates<br />

Nigeria<br />

Manufacturing, value added<br />

(% of GDP) average China,<br />

Brazil, India; SA<br />

Reihe8<br />

24

Nigeria, Iran, Algeria, Sambia, Saudi-Arabia<br />

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC VII<br />

Fig. 9: Real effective exchange rates<br />

Real effective exchange rates (index 2005 = 100)<br />

700<br />

200<br />

Algeria (lhs)<br />

600<br />

Nigeria (lhs)<br />

Venezuela<br />

180<br />

Iran (lhs)<br />

Iran (lhs)<br />

160<br />

Nigeria (lhs)<br />

500<br />

140<br />

Saudi Arabia (rhs)<br />

400<br />

Norway<br />

120<br />

100<br />

Zambia (lhs)<br />

Chile (rhs)<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

1980<br />

1981<br />

1982<br />

Saudi-Arabia<br />

Zambia<br />

1983<br />

1984<br />

1985<br />

1986<br />

1987<br />

1988<br />

1989<br />

Algeria<br />

(lhs)<br />

Russian<br />

Federation<br />

1990<br />

1991<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

2005<br />

2006<br />

2007<br />

2008<br />

2009<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

Ecuador (rhs)<br />

Norway (rhs)<br />

South Africa (rhs)<br />

Venezuela (rhs)<br />

Russian Federation<br />

(rhs)<br />

25

Empirical Evidence for DD <strong>and</strong> RC VIII<br />

• The magnitude of the resource rent, as calculated by the World Bank,<br />

was in 2005 on average 48 per cent of GDP<br />

• most OPEC countries have remained mono exporters of oil <strong>and</strong>/or gas<br />

• Contrary to st<strong>and</strong>ard DD theory, in the period between 1970 <strong>and</strong> 2009<br />

growth of manufacturing output was quite diverse, but often starting<br />

from a very low level<br />

• There is a broad spectrum of manufacturing (value added) as a share<br />

of GDP, in general much lower than in emerging economies<br />

• The majority of 17 energy-rich countries analysed achieved fairly low<br />

inflation over the 50 years, but some fell in high or even hyperinflation<br />

• In boom periods, there is a trend to real appreciation, but in some<br />

countries the exchange rate is pegged to the US-$ (e.g. several Middle<br />

East countries)<br />

• 1n the 1980s <strong>and</strong> until 1999, many commodity exporters incurred high<br />

external debt using resources as collateral to weather the oil slump,<br />

<strong>and</strong> often fell in over-indebtedness 26<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

Empirical evidence IX: External Saving<br />

• Gelb & Associates (1988) analyzed the first two oil price booms of<br />

the 1970s for a sample of six developing countries<br />

• They concluded that with hindsight the governments should have<br />

saved more abroad <strong>and</strong> spent less at home recycling of petrodollars<br />

via capital markets<br />

• During the recent oil <strong>and</strong> commodity boom this policy had been<br />

implemented to a higher degree than formerly<br />

• Saving abroad is difficult for poor resource-rich <strong>and</strong> populous<br />

countries (e.g. Angola, Nigeria) – they desire more consumption<br />

<strong>and</strong> investment immediately<br />

• Especially in most OPEC countries <strong>and</strong> in Norway, external saving<br />

<strong>and</strong> active exchange rate management were cornerstones of oil<br />

management.<br />

• In contrast, Angola, Venezuela <strong>and</strong>, to a lesser extent, Nigeria<br />

opted for the spending strategy, often with inflationary results<br />

• Norway, often seen as a model, invests oil/gas windfalls abroad as<br />

a pension fund <strong>and</strong> uses only the returns domestically, besides<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

27

Indonesia – Successfully Escaping <strong>Dutch</strong><br />

<strong>Disease</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong><br />

• The economy managed to grow quickly <strong>and</strong> achieved a<br />

thorough diversification of its economy towards robust <strong>and</strong><br />

diversified industrialization<br />

• It seems that the early exhaustion of oil reserves triggered<br />

diversification of the economy (peak in 1977), but gas extraction<br />

was partly a substitute<br />

• Windfalls crowded out agricultural employment, not<br />

manufacturing, triggering strong productivity increases in<br />

agriculture<br />

• Overall, Indonesia managed to avoid debt-led industrialisation<br />

with windfall inflows that were – despite high corruption –<br />

successfully used for the modernisation of agriculture <strong>and</strong> for<br />

fostering manufacturing, while keeping the real exchange rate in<br />

the long run fairly stable, despite longer periods of overvaluation<br />

• Perhaps it is better to have some natural resources, but not too<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

28

Nigeria – <strong>Dutch</strong> disease, <strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> Poor Institutions<br />

• All characteristics of DD <strong>and</strong> RC can be seen in Nigeria at an<br />

extreme extent<br />

• Nigeria is <strong>and</strong> has been since the 1960s heavily oil-dependent<br />

• Manufacturing is still almost negligible<br />

• Use of windfalls for predominantly unproductive public investment<br />

• real exchange rate roller-coaster, severe inflation could not be<br />

avoided<br />

• The oil slumps after the booms in the 1970s were countered with<br />

heavy external borrowing (up to 193 per cent of GDP in 1993)<br />

• Absolute poverty increased from 1970 to 2000 from 36 to 70 per<br />

cent of the population.<br />

• Some authors blame “bad institutions” <strong>and</strong> corruption as the main<br />

cause of the Nigerian malaise<br />

• Note: a rentier economy with high profits from oil <strong>and</strong> gas windfalls,<br />

gives the government enormous power; this transforms the 29<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

Venezuela – no growth despite oilabundance<br />

Figure 10: Venezuela: GDP per capita 1980-2010<br />

Source: World Bank 2011, World Development Indicators, own calculations<br />

30<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

Venezuela – no growth despite oilabundance<br />

• Fairly high income p.c. level in Venezuela since long<br />

in PPP, but hardly any trend growth since 1980<br />

• Strong increase of average incomes in current US-$,<br />

but this view is deceptive: real incomes hardly rose<br />

• Nominal exchange rate is controlled, but inflation is<br />

not real appreciation<br />

• Spending effect dominates: much of windfalls is<br />

spent locally for consumption, in recent years in a<br />

pro-poor manner; Gini coefficient fell<br />

• Industrial sector is kept alive, often highly subsidized<br />

<strong>and</strong> inefficient<br />

• Venezuela suffers both DD <strong>and</strong> RC<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

31

Botswana – a very special case<br />

Botswana – a success model:<br />

• Botswana (only 2 Mio. inhabitants) benefits from wealth<br />

in diamonds remarkable continuous GDP growth with<br />

fairly low inflation<br />

• Economy strongly dependent on diamonds exports<br />

• In contrast to oil – steady increase of world market<br />

diamonds prices since five decades permanent boom<br />

• Very little diversification of industry – manufacturing<br />

neglegible, but strong civil service <strong>and</strong> parastatal sector<br />

• Increasing inequality of income distribution<br />

• Real exchange rate strongly managed by central bank<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

32

US$, p.c.<br />

index, 2005 = 100<br />

Norway – another special case<br />

100.000<br />

90.000<br />

80.000<br />

70.000<br />

60.000<br />

50.000<br />

40.000<br />

30.000<br />

20.000<br />

10.000<br />

0<br />

1970<br />

1972<br />

REER<br />

(downward =<br />

appreciation),<br />

rhs<br />

GDP p.c., constant US$,<br />

lhs<br />

Source: World Bank 2011, World<br />

Development Indicators, own calculations<br />

Norway: key indicators<br />

GDP p.c., PPP in<br />

constant US$, lhs<br />

1974<br />

1976<br />

1978<br />

1980<br />

1982<br />

1984<br />

1986<br />

1988<br />

1990<br />

1992<br />

nominal<br />

exchange rate<br />

(downward =<br />

appreciation),<br />

rhs<br />

GDP p.c., current US$, lhs<br />

1994<br />

1996<br />

1998<br />

2000<br />

2002<br />

current account<br />

balance, % of GDP,<br />

rhs<br />

2004<br />

2006<br />

2008<br />

33<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

2010<br />

160<br />

140<br />

120<br />

100<br />

80<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

-20

Norway – another special case<br />

• Oil <strong>and</strong> gas resources discovered in early 1970s, as a<br />

highly developed small country (5 mill. inhabitants)<br />

• Natural resources state-owned<br />

• Windfalls saved in a national fund abroad, used as a<br />

pension fund, amounting to 120 % of GDP<br />

• returns from the capital stock transferred to Norway<br />

• Social security contributions <strong>and</strong> taxes < average<br />

OECD countries indirectly consumption of windfalls<br />

• Low inflation, managed exchange rates<br />

• Low long-term per capita growth<br />

• High domestic prices, wages <strong>and</strong> cost level<br />

• Diversificcation of manufacturing unsuccessful<br />

• Industry centered on construction <strong>and</strong> maritime<br />

industries<br />

• 85,000 US-$ p.c., but in PPP 55,000 US-$ (2009/10)<br />

• Gini-cofficient as low as 0.258<br />

• Similar to Middle East, but equal distribution<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

34

6. COPING WITH DD AND RC :<br />

SEARCHING FOR POLICY<br />

STRATEGIES<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

35

Extraction Policy <strong>and</strong> use of resource rents<br />

• How much natural resource should be extracted How to<br />

use windfalls<br />

• Hotelling‘s Rule: extraction is conditional on maximization<br />

of rents - achieved if the long-term interest rate equals the<br />

expected net price increase of the natural resource. In<br />

reality, imperfect competition <strong>and</strong> high uncertainty<br />

predominate. Rule not really applicable under real world<br />

conditions<br />

• Hartwick-Rule stipulates that the loss of exhaustive<br />

natural resources by extraction can only be offset by using<br />

the resource rents for the generation of produced capital.<br />

Only the yields from this produced wealth should be be<br />

consumed. Rule for environmental sustainability<br />

• Neither the Hotelling-Rule nor the Hartwick-Rule deal<br />

directly with DD<br />

• Yet, containing DD is easier if the speed of extraction of 36<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

Alternative Strategies for <strong>Resource</strong>-rich<br />

Countries<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

37

What is the best strategy<br />

• Inflationary spending <strong>and</strong> resource movement effects<br />

should be mitigated<br />

• In poor countries use of windfalls for productive investment<br />

advisable - only if non-inflationary<br />

• When windfalls are huge, saving abroad is MUST to avoid<br />

inflation<br />

• Lower current account deficit, repay external debt<br />

• Use of rents for industrial <strong>and</strong> agricultural policy, incl.<br />

productive infrastructure <strong>and</strong> human capital formation<br />

• Monetary policy should target stabilization of REER or<br />

mitigating swings<br />

• Use mainly fiscal policy for keeping price stability<br />

• Save part of windfalls abroad, use for counter-cyclical<br />

policy to bridge slumps<br />

• Mind pro-rich distribution of rents<br />

38<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

7. CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

39

Conclusion <strong>and</strong> Outlook I<br />

• Windfalls tend to trigger real currency appreciation,<br />

depreciations in slumps<br />

• Avoid inflationary use of the windfalls, cope with volatility<br />

of resource prices<br />

• DD can evolve into an enduring RC if the core sector of<br />

technical progress <strong>and</strong> growth, manufacturing, is<br />

continuously suppressed<br />

• The terms “disease” <strong>and</strong> “curse” are a bit misleading, as<br />

wealth increases in booms if not offset in slumps or lost<br />

by inflation or de-industrialization<br />

• Bad “institutions” <strong>and</strong> “bad governance” are not the<br />

cause of DD <strong>and</strong> RC, but they exacerbate the problems<br />

• Among developing countries with strong resource<br />

dependence, the only model for more blessing than<br />

curse was Indonesia but it is a special case 40<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch

Conclusion <strong>and</strong> Outlook II<br />

• There is no quick <strong>and</strong> easy medicine for DD <strong>and</strong> RC<br />

• A new overwhelmingly strong comparative<br />

advantage squeezes more or less the comparatively<br />

disadvantageous sectors<br />

• A mix of saving abroad <strong>and</strong> spending for investment<br />

domestically is advisable, embedded in macro<br />

policies which stabilize the real exchange rate at a<br />

level competitive for non-resource tradables,<br />

especially manufactures<br />

• More generally, resource-rich economies are, more<br />

or less, rentier economies which differ from normal<br />

market economies. DD <strong>and</strong> RC concepts should be<br />

embedded in the political economy of rentier<br />

economies whose predominant income are rents<br />

from natural resources.<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

41

Literature<br />

• Corden, W.M. <strong>and</strong> Neary, J.P. (1982). “Booming Sector <strong>and</strong> De-<br />

Industrialisation in a Small Open Economy”. The Economic Journal, 92<br />

(December 1982): 825-848.<br />

• As a first quick introduction: Ebrahim-zadeh, Ch., 2003: <strong>Dutch</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>:<br />

Too much wealth managed unwisely. In: Finance & Development, Vol.<br />

40, March, No. 1<br />

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/f<strong>and</strong>d/2003/03/ebra.htm<br />

• Gelb, A. <strong>and</strong> Associates (1988). Oil Windfalls: Blessing or <strong>Curse</strong><br />

Published for the World Bank. Oxford, Oxford University Press.<br />

• Humphreys, M., Sachs, J. <strong>and</strong> Stiglitz, J.E., Eds. (2007). Escaping the<br />

<strong>Resource</strong> <strong>Curse</strong>. New York, Columbia University Press.<br />

• Sachs, J.D., <strong>and</strong> Warner, A.M. (2001). “The <strong>Curse</strong> of Natural<br />

<strong>Resource</strong>s”. European Economic Review, 45(4-6): 827-838.<br />

• UNCTAD (2008): The Least Developed Countries Report 2009: The<br />

state <strong>and</strong> developing governance. Background Paper No. 4 (April 2008)<br />

by Jourdan, P. (2008): Challenges of LDC <strong>Resource</strong>-Based Development.<br />

Geneva.<br />

UNCTAD Division on Technology <strong>and</strong> Logistics - Knowledge Sharing, Training <strong>and</strong> Capacity Development Branch<br />

42