Walking and Cycling International Literature Review - Department of ...

Walking and Cycling International Literature Review - Department of ...

Walking and Cycling International Literature Review - Department of ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

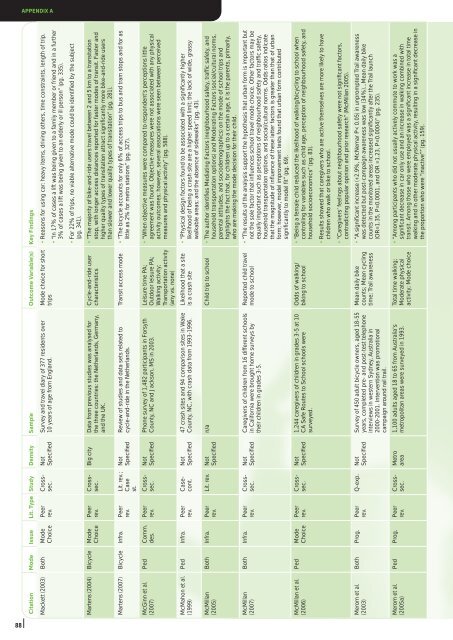

APPENDIX A<br />

Citation Mode Issue Lit. Type Study Density Sample Outcome Variable(s) Key Findings<br />

Mackett (2003) Both Mode<br />

Choice<br />

Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Not<br />

Specified<br />

Survey <strong>and</strong> travel diary <strong>of</strong> 377 residents over<br />

10 years <strong>of</strong> age from Engl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Mode choice for short<br />

trips<br />

• Reasons for using car: heavy items, driving others, time constraints, length <strong>of</strong> trip.<br />

• “In 17% <strong>of</strong> cases a lift was being given to a family member or friend <strong>and</strong> in a further<br />

3% <strong>of</strong> cases a lift was being given to an elderly or ill person” (pg. 335).<br />

• For 22% <strong>of</strong> trips, no viable alternative mode could be identified by the subject<br />

(pg. 341).<br />

Martens (2004) Bicycle Mode<br />

Choice<br />

Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Big city Data from previous studies was analysed for<br />

the three countries: the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, Germany,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the UK.<br />

Cycle-<strong>and</strong>-ride user<br />

characteristics<br />

• “The majority <strong>of</strong> bike-<strong>and</strong>-ride users travel between 2 <strong>and</strong> 5 km to a transitation<br />

stop, with longer access distances reported for faster modes <strong>of</strong> transit. Faster <strong>and</strong><br />

higher quality types <strong>of</strong> transitation attract significantly more bike-<strong>and</strong>-ride users<br />

than slower <strong>and</strong> lower quality types <strong>of</strong> transitation” (pg. 281).<br />

Martens (2007) Bicycle Infra. Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Lit. rev.;<br />

Case<br />

st.<br />

Not<br />

Specified<br />

<strong>Review</strong> <strong>of</strong> studies <strong>and</strong> data sets related to<br />

cycle-<strong>and</strong>-ride in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

Transit access mode • “The bicycle accounts for only 6% <strong>of</strong> access trips to bus <strong>and</strong> tram stops <strong>and</strong> for as<br />

little as 2% for metro stations” (pg. 327).<br />

McGinn et al.<br />

(2007)<br />

Ped Comm.<br />

des.<br />

Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Not<br />

Specified<br />

Phone survey <strong>of</strong> 1,482 participants in Forsyth<br />

County, NC <strong>and</strong> Jackson, MS in 2003.<br />

Leisure time PA;<br />

Outdoor leisure PA;<br />

<strong>Walking</strong> activity;<br />

Transportation activity<br />

(any vs. none)<br />

• “When objective measures were compared to respondent’s perceptions little<br />

agreement was found. Objective measures were not associated with any physical<br />

activity outcomes; however, several associations were seen between perceived<br />

measures <strong>and</strong> physical activity” (pg. 588).<br />

McMahon et al.<br />

(1999)<br />

Ped Infra. Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Not<br />

Specified<br />

47 crash sites <strong>and</strong> 94 comparison sites in Wake<br />

County, NC, with crash data from 1993-1996.<br />

Likelihood that a site<br />

is a crash site<br />

• “Physical design factors found to be associated with a significantly higher<br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> being a crash site are a higher speed limit; the lack <strong>of</strong> wide, grassy<br />

walkable areas; <strong>and</strong> the absence <strong>of</strong> sidewalks” (pg. 43).<br />

McMillan<br />

(2005)<br />

Both Infra. Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Lit. rev. Not<br />

Specified<br />

n/a Child trip to school • The author identifies Mediating Factors (neighbourhood safety, traffic safety, <strong>and</strong><br />

household transportation options) <strong>and</strong> Moderating Factors (social/cultural norms,<br />

parental attitudes, <strong>and</strong> sociodemographics) on the mode <strong>of</strong> school trips <strong>and</strong><br />

highlights the fact that, for children up to a certain age, it is the parents, primarily,<br />

who are making the mode decision for their child.<br />

McMillan<br />

(2007)<br />

Both Infra. Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Not<br />

Specified<br />

Caregivers <strong>of</strong> children from 16 different schools<br />

in California were brought home surveys by<br />

their children in grades 3-5.<br />

Reported child travel<br />

mode to school<br />

• “The results <strong>of</strong> the analysis support the hypothesis that urban form is important but<br />

not the sole factor that influences school travel mode choice. Other factors may be<br />

equally important such as perceptions <strong>of</strong> neighbourhood safety <strong>and</strong> traffic safety,<br />

household transportation options, <strong>and</strong> social/cultural norms. Odds ratios indicate<br />

that the magnitude <strong>of</strong> influence <strong>of</strong> these latter factors is greater than that <strong>of</strong> urban<br />

form; however, model improvement tests found that urban form contributed<br />

significantly to model fit” (pg. 69).<br />

McMillan et al.<br />

(2006)<br />

Ped Mode<br />

Choice<br />

Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Not<br />

Specified<br />

1,244 caregivers <strong>of</strong> children in grades 3-5 at 10<br />

CA Safe Routes to School schools were<br />

surveyed.<br />

Odds <strong>of</strong> walking/<br />

biking to school<br />

• “Being a female child reduced the likelihood <strong>of</strong> walking/bicycling to school when<br />

controlling for variables such as child age, perception <strong>of</strong> neighbourhood safety, <strong>and</strong><br />

household socioeconomics” (pg. 83).<br />

• Results showed that caregivers who are active themselves are more likely to have<br />

children who walk or bike to school.<br />

• “Caregivers’ feelings about neighbourhood safety were not significant factors,<br />

contradicting popular opinion <strong>and</strong> prior research” (McMillan 2005).<br />

Merom et al.<br />

(2003)<br />

Both Prog. Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Q-exp. Not<br />

Specified<br />

Survey <strong>of</strong> 450 adult bicycle owners, aged 18-55<br />

years, completed pre- <strong>and</strong> post-test telephone<br />

interviews in western Sydney, Australia in<br />

2000-2001. Intervention was promotional<br />

campaign around rail trail.<br />

Mean daily bike<br />

counts; Mean cycling<br />

time; Trail awareness<br />

• “A significant increase (+2.9%, McNemar P< 0.05) in unprompted Trail awareness<br />

was detected but post-campaign awareness was low (34%)...Mean daily bike<br />

counts in the monitored areas increased significantly after the Trail launch<br />

(OR=1.35, P=0.0001, <strong>and</strong> OR =1.23, P=0.0004)” (pg. 235).<br />

Merom et al.<br />

(2005a)<br />

Ped Prog. Peer<br />

rev.<br />

Crosssec.<br />

Crosssec.<br />

Crosssec.<br />

Casecont.<br />

Crosssec.<br />

Crosssec.<br />

Crosssec.<br />

Metro<br />

area<br />

1,100 adults aged 18 to 65 from Australia's<br />

metropolitan areas were surveyed in 1993.<br />

Total time walking;<br />

Moderate physical<br />

activity; Mode choice<br />

• “Among participants who did not usually actively commute to work was a<br />

significant decrease in car only use <strong>and</strong> an increase in walking combined with<br />

transit. Among those who were employed was a significant increase in total time<br />

walking <strong>and</strong> in other moderate physical activity, resulting in a significant decrease in<br />

the proportion who were “inactive”” (pg. 159).<br />

88