A land manager's guide to conserving habitat for forest birds in ...

A land manager's guide to conserving habitat for forest birds in ...

A land manager's guide to conserving habitat for forest birds in ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

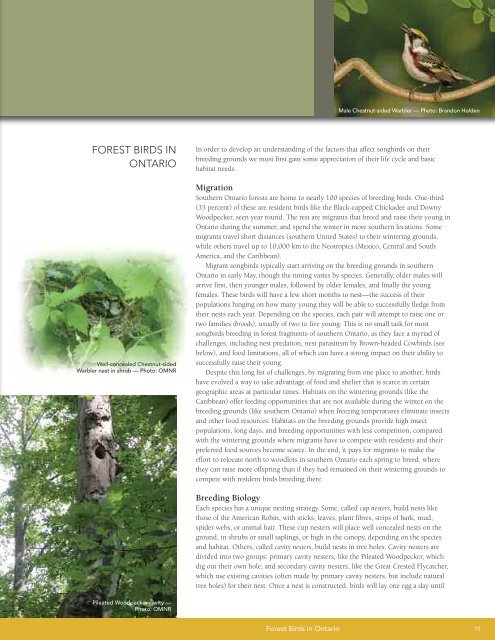

Male Chestnut-sided Warbler — Pho<strong>to</strong>: Brandon Holden<br />

FOREST BIRDS IN<br />

ONTARIO<br />

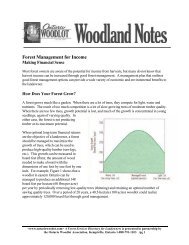

Well-concealed Chestnut-sided<br />

Warbler nest <strong>in</strong> shrub — Pho<strong>to</strong>: OMNR<br />

In order <strong>to</strong> develop an understand<strong>in</strong>g of the fac<strong>to</strong>rs that affect song<strong>birds</strong> on their<br />

breed<strong>in</strong>g grounds we must first ga<strong>in</strong> some appreciation of their life cycle and basic<br />

<strong>habitat</strong> needs.<br />

Migration<br />

Southern Ontario <strong>for</strong>ests are home <strong>to</strong> nearly 100 species of breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>birds</strong>. One-third<br />

(33 percent) of these are resident <strong>birds</strong> like the Black-capped Chickadee and Downy<br />

Woodpecker, seen year round. The rest are migrants that breed and raise their young <strong>in</strong><br />

Ontario dur<strong>in</strong>g the summer, and spend the w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>in</strong> more southern locations. Some<br />

migrants travel short distances (southern United States) <strong>to</strong> their w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g grounds,<br />

while others travel up <strong>to</strong> 10,000 km <strong>to</strong> the Neotropics (Mexico, Central and South<br />

America, and the Caribbean).<br />

Migrant song<strong>birds</strong> typically start arriv<strong>in</strong>g on the breed<strong>in</strong>g grounds <strong>in</strong> southern<br />

Ontario <strong>in</strong> early May, though the tim<strong>in</strong>g varies by species. Generally, older males will<br />

arrive first, then younger males, followed by older females, and f<strong>in</strong>ally the young<br />

females. These <strong>birds</strong> will have a few short months <strong>to</strong> nest—the success of their<br />

populations h<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g on how many young they will be able <strong>to</strong> successfully fledge from<br />

their nests each year. Depend<strong>in</strong>g on the species, each pair will attempt <strong>to</strong> raise one or<br />

two families (broods), usually of two <strong>to</strong> five young. This is no small task <strong>for</strong> most<br />

song<strong>birds</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>for</strong>est fragments of southern Ontario, as they face a myriad of<br />

challenges, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g nest predation, nest parasitism by Brown-headed Cow<strong>birds</strong> (see<br />

below), and food limitations, all of which can have a strong impact on their ability <strong>to</strong><br />

successfully raise their young.<br />

Despite this long list of challenges, by migrat<strong>in</strong>g from one place <strong>to</strong> another, <strong>birds</strong><br />

have evolved a way <strong>to</strong> take advantage of food and shelter that is scarce <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong><br />

geographic areas at particular times. Habitats on the w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g grounds (like the<br />

Caribbean) offer feed<strong>in</strong>g opportunities that are not available dur<strong>in</strong>g the w<strong>in</strong>ter on the<br />

breed<strong>in</strong>g grounds (like southern Ontario) when freez<strong>in</strong>g temperatures elim<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong>sects<br />

and other food resources. Habitats on the breed<strong>in</strong>g grounds provide high <strong>in</strong>sect<br />

populations, long days, and breed<strong>in</strong>g opportunities with less competition, compared<br />

with the w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g grounds where migrants have <strong>to</strong> compete with residents and their<br />

preferred food sources become scarce. In the end, it pays <strong>for</strong> migrants <strong>to</strong> make the<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>t <strong>to</strong> relocate north <strong>to</strong> woodlots <strong>in</strong> southern Ontario each spr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> breed, where<br />

they can raise more offspr<strong>in</strong>g than if they had rema<strong>in</strong>ed on their w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g grounds <strong>to</strong><br />

compete with resident <strong>birds</strong> breed<strong>in</strong>g there.<br />

Breed<strong>in</strong>g Biology<br />

Each species has a unique nest<strong>in</strong>g strategy. Some, called cup nesters, build nests like<br />

those of the American Rob<strong>in</strong>, with sticks, leaves, plant fibres, strips of bark, mud,<br />

spider webs, or animal hair. These cup nesters will place well concealed nests on the<br />

ground, <strong>in</strong> shrubs or small sapl<strong>in</strong>gs, or high <strong>in</strong> the canopy, depend<strong>in</strong>g on the species<br />

and <strong>habitat</strong>. Others, called cavity nesters, build nests <strong>in</strong> tree holes. Cavity nesters are<br />

divided <strong>in</strong><strong>to</strong> two groups: primary cavity nesters, like the Pileated Woodpecker, which<br />

dig out their own hole; and secondary cavity nesters, like the Great Crested Flycatcher,<br />

which use exist<strong>in</strong>g cavities (often made by primary cavity nesters, but <strong>in</strong>clude natural<br />

tree holes) <strong>for</strong> their nest. Once a nest is constructed, <strong>birds</strong> will lay one egg a day until<br />

Pileated Woodpecker cavity —<br />

Pho<strong>to</strong>: OMNR<br />

Forest Birds <strong>in</strong> Ontario 15