A land manager's guide to conserving habitat for forest birds in ...

A land manager's guide to conserving habitat for forest birds in ...

A land manager's guide to conserving habitat for forest birds in ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Male Northern Card<strong>in</strong>al feed<strong>in</strong>g recently<br />

fledged young — Pho<strong>to</strong>: Marie Read<br />

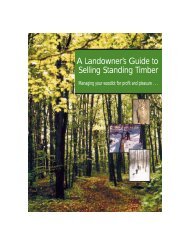

Ovenbird nest and<br />

surround<strong>in</strong>g <strong>habitat</strong><br />

— Pho<strong>to</strong>: Ken Elliott<br />

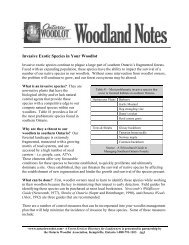

Close-up of<br />

Ovenbird nest —<br />

Pho<strong>to</strong>: Ken Elliott<br />

This <strong>in</strong> turn governs the range of <strong>habitat</strong>s available <strong>to</strong> different<br />

organisms. Generally, <strong>for</strong>ests that have many layers from the<br />

ground <strong>to</strong> the canopy will support a greater array of plant and<br />

animal species compared <strong>to</strong> <strong>for</strong>ests <strong>in</strong> which the vegetation is<br />

concentrated <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle layer. Lack of vegetation structure will<br />

have negative effects on species that rely on specific layers of<br />

vegetation <strong>for</strong> food or cover. Terri<strong>to</strong>ries of different species can<br />

overlap horizontally and vertically with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>for</strong>est.<br />

Suites of species that have similar <strong>habitat</strong> requirements are<br />

often grouped accord<strong>in</strong>g <strong>to</strong> a nest<strong>in</strong>g or <strong>for</strong>ag<strong>in</strong>g guild. Some <strong>birds</strong><br />

prefer open, shrubby <strong>habitat</strong> found <strong>in</strong> young <strong>for</strong>ests (i.e., early<br />

successional guild), whereas others prefer closed canopy <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

with large trees and belong <strong>to</strong> the mature <strong>for</strong>est. For an <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

bird, select<strong>in</strong>g suitable <strong>habitat</strong> can have the greatest <strong>in</strong>fluence on<br />

its ability <strong>to</strong> survive and reproduce. Faced with a multitude of<br />

possible choices <strong>in</strong> the <strong>land</strong>scape, how do <strong>birds</strong> choose the most<br />

appropriate <strong>habitat</strong>? They do this by mak<strong>in</strong>g a series of choices,<br />

first at very large or coarse scales (e.g., all of southern Ontario),<br />

then at <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly f<strong>in</strong>er, smaller scales. For example, an<br />

Ovenbird (a small ground nest<strong>in</strong>g bird with bold breast spots,<br />

that returns <strong>to</strong> breed <strong>in</strong> the woodlots of southern Ontario <strong>in</strong> the<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>g), first chooses a <strong>for</strong>est patch. This may be based on the<br />

size of the patch, the surround<strong>in</strong>g <strong>land</strong>scape features, and<br />

adjacent <strong>land</strong> uses. Next it will have <strong>to</strong> choose a terri<strong>to</strong>ry with<strong>in</strong><br />

that patch. This will be based on the structure of the <strong>for</strong>est and<br />

the availability of food with<strong>in</strong> it. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the Ovenbird will choose<br />

a nest site. Oven<strong>birds</strong> nest on the ground and will look <strong>for</strong><br />

particular vegetation features and structures that may hide the<br />

nest from preda<strong>to</strong>rs and cow<strong>birds</strong>.<br />

The Reproductive Challenge<br />

Although each bird attempts <strong>to</strong> raise as many young as possible<br />

over its lifetime, <strong>to</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a population, births must equal deaths.<br />

Each adult, with<strong>in</strong> its lifespan, must replace itself with an offspr<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of reproductive age. For most song<strong>birds</strong> this means a pair must<br />

produce one young that survives <strong>to</strong> the next breed<strong>in</strong>g season. This<br />

may not seem difficult over an average life span of two <strong>to</strong> three<br />

years, given that most <strong>birds</strong> lay three <strong>to</strong> four eggs per nest, and<br />

many can produce more than one successful nest per year (double<br />

brood<strong>in</strong>g). However, once you consider rates of nest failure (50–80<br />

percent) and losses due <strong>to</strong> parasitism (15–50 percent of nests are<br />

parasitized and fledge half as many young), the probability of<br />

those eggs successfully hatch<strong>in</strong>g and the young surviv<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>to</strong> return and breed is greatly reduced. As well, once a<br />

nestl<strong>in</strong>g has left the nest, its survival is often very poor with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

first week of life, never m<strong>in</strong>d the additional challenges of<br />

migration and over-w<strong>in</strong>ter survival!<br />

20<br />

Forest Birds <strong>in</strong> Ontario