Guidelines on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris ... - Cardio

Guidelines on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris ... - Cardio

Guidelines on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris ... - Cardio

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> 3societies and translated into <strong>the</strong> local language, whennecessary.All in all, <strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong> writing <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> or ExpertC<strong>on</strong>sensus Document covers not <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>the</strong> integrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>most recent research but also <strong>the</strong> creati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> educati<strong>on</strong>altools and implementati<strong>on</strong> programmes for <strong>the</strong> recommendati<strong>on</strong>s.The loop between clinical research, writing <strong>of</strong>guidelines, and implementing <strong>the</strong>m into clinical practicecan <strong>the</strong>n <strong>on</strong>ly be completed if surveys and registries areorganized to verify that actual clinical practice is inkeeping with what is recommended in <strong>the</strong> guidelines. Suchsurveys and registries also make it possible to check <strong>the</strong>impact <strong>of</strong> strict implementati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> guidelines <strong>on</strong>patient outcome.Classes <strong>of</strong> Recommendati<strong>on</strong>sClass IClass IIClass IIaClass IIbClass IIIEvidence and/or general agreement that a givendiagnostic procedure/treatment is beneficial,useful, and effectiveC<strong>on</strong>flicting evidence and/or a divergence <strong>of</strong> opini<strong>on</strong>about <strong>the</strong> usefulness/efficacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> treatmentor procedureWeight <strong>of</strong> evidence/opini<strong>on</strong> is in favour <strong>of</strong>usefulness/efficacyUsefulness/efficacy is less well established byevidence/opini<strong>on</strong>Evidence or general agreement that <strong>the</strong> treatmentor procedure is not useful/effective and, in somecases, may be harmfulLevel <strong>of</strong> evidence A Data derived from multiple randomizedclinical trials or meta-analysesLevel <strong>of</strong> evidence B Data derived from a single randomizedclinical trial or large n<strong>on</strong>-randomizedstudiesLevel <strong>of</strong> evidence C C<strong>on</strong>sensus <strong>of</strong> opini<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> experts and/orsmall studies, retrospective studies, andregistriesIntroducti<strong>on</strong><strong>Stable</strong> angina pectoris is a comm<strong>on</strong> and disabling disorder.However, <strong>the</strong> management <strong>of</strong> stable angina has not beensubjected to <strong>the</strong> same scrutiny by large randomized trialsas has, for example, that <strong>of</strong> acute cor<strong>on</strong>ary syndromes(ACS) including unstable angina and myocardial infarcti<strong>on</strong>(MI). The optimal strategy <strong>of</strong> investigati<strong>on</strong> and treatmentis difficult to define, and <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> new tools for<strong>the</strong> diagnostic and prognostic assessment <strong>of</strong> patients,al<strong>on</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tinually evolving evidence base forvarious treatment strategies, mandates that <strong>the</strong> existingguidelines be revised and updated. The Task Force has<strong>the</strong>refore obtained opini<strong>on</strong>s from a wide variety <strong>of</strong> expertsand has tried to achieve agreement <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> best c<strong>on</strong>temporaryapproaches to <strong>the</strong> care <strong>of</strong> stable angina pectoris, bearingin mind not <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>the</strong> efficacy and safety <strong>of</strong> treatments butalso <strong>the</strong> cost and <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> resources. The TaskForce has taken <strong>the</strong> view that <strong>the</strong>se guidelines shouldreflect <strong>the</strong> pathophysiology and management <strong>of</strong> angina pectoris,namely myocardial ischaemia due to cor<strong>on</strong>ary arterydisease (CAD), usually macrovascular, i.e. involving largecor<strong>on</strong>ary arteries, but also microvascular in some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>patients. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, this Task Force does not deal withprimary preventi<strong>on</strong>, which has already been covered ino<strong>the</strong>r recently published guidelines 1 and has limited its discussi<strong>on</strong><strong>on</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>dary preventi<strong>on</strong>. Recently published guidelinesand c<strong>on</strong>sensus statements that overlap to ac<strong>on</strong>siderable extent with <strong>the</strong> remit <strong>of</strong> this document arelisted in Table 1.Definiti<strong>on</strong> and pathophysiology<strong>Stable</strong> angina is a clinical syndrome characterized bydiscomfort in <strong>the</strong> chest, jaw, shoulder, back, or arms, typicallyelicited by exerti<strong>on</strong> or emoti<strong>on</strong>al stress and relievedby rest or nitroglycerin. Less typically, discomfort mayoccur in <strong>the</strong> epigastric area. William Heberden first introduced<strong>the</strong> term ‘angina pectoris’ in 1772 2 to characterizea syndrome in which <strong>the</strong>re was ‘a sense <strong>of</strong> strangling andanxiety’ in <strong>the</strong> chest, especially associated with exercise,although its pathological aetiology was not recognizeduntil some years later. 3 It is now usual to c<strong>on</strong>fine <strong>the</strong>term to cases in which <strong>the</strong> syndrome can be attributed tomyocardial ischaemia, although essentially similar symptomscan be caused by disorders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oesophagus,lungs, or chest wall. Although <strong>the</strong> most comm<strong>on</strong> cause <strong>of</strong>myocardial ischaemia is a<strong>the</strong>rosclerotic CAD, dem<strong>on</strong>strablemyocardial ischaemia may be induced in <strong>the</strong> abscence byhypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis,or o<strong>the</strong>r rare cardiac c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> obstructivea<strong>the</strong>romatous cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease, which are notc<strong>on</strong>sidered in this document.Myocardial ischaemia is caused by an imbalance betweenmyocardial oxygen supply and myocardial oxygen c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong>.Myocardial oxygen supply is determined by arterialoxygen saturati<strong>on</strong> and myocardial oxygen extracti<strong>on</strong>,which are relatively fixed under normal circumstances,and cor<strong>on</strong>ary flow, which is dependent <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> luminal crosssecti<strong>on</strong>alarea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary artery and cor<strong>on</strong>ary arteriolart<strong>on</strong>e. Both cross-secti<strong>on</strong>al area and arterioloar t<strong>on</strong>e may bedramatically altered by <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> a<strong>the</strong>roscleroticplaque within <strong>the</strong> vessel wall, leading to imbalancebetween supply and demand when myocardial oxygendemands increase, as during exerti<strong>on</strong>, related to increasesin heart rate, myocardial c<strong>on</strong>tractility, and wall stress.Ischaemia-induced sympa<strong>the</strong>tic activati<strong>on</strong> can fur<strong>the</strong>rincrease <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> ischaemia through a variety <strong>of</strong>mechanisms including a fur<strong>the</strong>r increase <strong>of</strong> myocardialoxygen c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> and cor<strong>on</strong>ary vasoc<strong>on</strong>stricti<strong>on</strong>. Theischaemic cascade is characterized by a sequence <strong>of</strong>events, resulting in metabolic abnormalities, perfusi<strong>on</strong> mismatch,regi<strong>on</strong>al and <strong>the</strong>n global diastolic and systolic dysfuncti<strong>on</strong>,electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, and angina.Adenosine released by ischaemic myocardium appears tobe <strong>the</strong> main mediator <strong>of</strong> angina (chest pain) through stimulati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> A1 receptors located <strong>on</strong> cardiac nerve endings. 4Ischaemia is followed by reversible c<strong>on</strong>tractile dysfuncti<strong>on</strong>known as ‘stunning’. Recurrent episodes <strong>of</strong> ischaemia and

ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> 5or at rest. 11 MI is characterized by prol<strong>on</strong>ged angina(.30 min) associated with myocardial necrosis. 12 Bothn<strong>on</strong>-ST-elevati<strong>on</strong> and ST-elevati<strong>on</strong> MI are frequently precededby a period <strong>of</strong> days, or even weeks, <strong>of</strong> unstable symptoms.The comm<strong>on</strong> pathological background <strong>of</strong> ACS is erosi<strong>on</strong>,fissure, or rupture <strong>of</strong> an a<strong>the</strong>rosclerotic cor<strong>on</strong>ary plaqueassociated with platelet aggregati<strong>on</strong>, leading to subtotal ortotal thrombotic cor<strong>on</strong>ary occlusi<strong>on</strong>. Activated plateletsrelease a number <strong>of</strong> vasoc<strong>on</strong>strictors, which may fur<strong>the</strong>rimpair cor<strong>on</strong>ary flow through <strong>the</strong> stimulati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> vascularsmooth muscle cells both locally and distally. The haemodynamicseverity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> a<strong>the</strong>rosclerotic plaque prior to destabilizati<strong>on</strong>is frequently mild and <strong>the</strong> plaques are lipid filledwith foam cells. Intravascular ultrasound studies haveshown that so-called vulnerable plaques (i.e. at risk <strong>of</strong> caprupture) that are ,50% in diameter both precede andpredict future acute syndromes occurring precisely in <strong>the</strong>irneighbourhood. 13 Activati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> inflammatory cells within<strong>the</strong> a<strong>the</strong>rosclerotic plaque appears to play an importantrole in <strong>the</strong> destabilizati<strong>on</strong> process, 14 leading to plaqueerosi<strong>on</strong>, fissure, or rupture. More recently, <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cept <strong>of</strong> asingle vulnerable plaque causing an ACS has been challengedin favour <strong>of</strong> a more generalized inflammatory resp<strong>on</strong>se. 15EpidemiologyAs angina is essentially a diagnosis based <strong>on</strong> history, and<strong>the</strong>refore subjective, it is understandable that its prevalenceand incidence have been difficult to assess and mayvary between studies dependent <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> definiti<strong>on</strong> that hasbeen used.For epidemiological purposes, <strong>the</strong> L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong> School <strong>of</strong>Hygiene and Tropical Medicine cardiovascular questi<strong>on</strong>naire,devised by Rose and Blackburn 16 and adopted by <strong>the</strong> WHO,has been widely used. It defines angina as chest pain,pressure, or heaviness that limits exerti<strong>on</strong>, is situated over<strong>the</strong> sternum or in <strong>the</strong> left chest and left arm, and is relievedwithin 10 min <strong>of</strong> rest. The questi<strong>on</strong>naire allows a subdivisi<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> symptoms into definite and possible angina, which can befur<strong>the</strong>r subdivided into grade 1 and grade 2. 17 It should berecognized that this questi<strong>on</strong>naire is a screening tool andnot a diagnostic test.Rose angina questi<strong>on</strong>naire predicts cardiovascular morbidityand mortality in European 18,19 and American populati<strong>on</strong>s, 20independent <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r risk factors. Therefore, it has beenindirectly validated. It has been compared with o<strong>the</strong>rstandards including a clinical diagnosis, 21 ECG findings, 22radi<strong>on</strong>uclide tests, 23 and cor<strong>on</strong>ary arteriography. 24 On <strong>the</strong>basis <strong>of</strong> such comparis<strong>on</strong>s, its specificity is 80–95% but itssensitivity varies greatly from 20 to 80%. The exerti<strong>on</strong>alcomp<strong>on</strong>ent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> symptoms is crucial to <strong>the</strong> diagnosticaccuracy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> questi<strong>on</strong>aire, 18 and its performance seemsto be less accurate in women. 25The prevalence <strong>of</strong> angina in community studies increasessharply with age in both sexes from 0.1–1% in women aged45–54 to 10–15% in women aged 65–74 and from 2–5% inmen aged 45–54 to 10–20% in men aged 65–74. 26–33Therefore, it can be estimated that in most Europeancountries, 20 000–40 000 individuals <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> permilli<strong>on</strong> suffer from angina.Community-based informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> incidence <strong>of</strong> anginapectoris is derived from prospective, epidemiologic studieswith repeated examinati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cohort. Such studieshave been scarce over recent years. Available data, from<strong>the</strong> Seven Countries study, 34 studies in <strong>the</strong> UK, 35,36 <strong>the</strong>Israel Ischaemic Heart Disease study, 37 <strong>the</strong> H<strong>on</strong>olulu Heartstudy, 38 <strong>the</strong> Framingham study 39,40 and o<strong>the</strong>rs, 41 suggestan annual incidence <strong>of</strong> uncomplicated angina pectoris<strong>of</strong> 0.5% in western populati<strong>on</strong>s aged .40, but withgeographic variati<strong>on</strong>s evident.A more recent study, using a different definiti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> anginabased <strong>on</strong> case descripti<strong>on</strong> by clinicians, which definedangina pectoris as <strong>the</strong> associati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> chest pain at rest or<strong>on</strong> exerti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>on</strong>e positive finding from a cardiovascularexaminati<strong>on</strong> such as arteriography, scintigraphy, exercisetesting, or resting ECG, 42 c<strong>on</strong>firm geographical variati<strong>on</strong>sin <strong>the</strong> incidence <strong>of</strong> angina which occur in parallel withobserved internati<strong>on</strong>al differences in cor<strong>on</strong>ary heartdisease (CHD) mortality. The incidence <strong>of</strong> angina pectorisas a first cor<strong>on</strong>ary event was approximately twice high inBelfast compared with France (5.4 per 1000 pers<strong>on</strong>-yearscompared with 2.6).Temporal trends suggest a decrease in <strong>the</strong> prevalence <strong>of</strong>angina pectoris in recent decades 35,43 in line with falling cardiovascularmortality rates observed in <strong>the</strong> MONICA 44 study.However, <strong>the</strong> prevalence <strong>of</strong> a history <strong>of</strong> diagnosed CHD doesnot appear to have decreased, suggesting that althoughfewer people are developing angina due to changes in lifestyleand risk factors, those who have cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease areliving l<strong>on</strong>ger with <strong>the</strong> disease. Improved sensitivity <strong>of</strong> diagnostictools may additi<strong>on</strong>ally c<strong>on</strong>tribute to <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>temporaryhigh prevalence <strong>of</strong> diagnosed CHD.Natural history and prognosisInformati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> prognosis associated with chr<strong>on</strong>ic stableangina is derived from l<strong>on</strong>g-term prospective, populati<strong>on</strong>basedstudies, clinical trials <strong>of</strong> antianginal <strong>the</strong>rapy, andobservati<strong>on</strong>al registries, with selecti<strong>on</strong> bias an importantfactor to c<strong>on</strong>sider when evaluating and comparing <strong>the</strong> availabledata. European data estimate <strong>the</strong> cardiovasculardisease (CVD) mortality rate and CHD mortality rates formen with Rose questi<strong>on</strong>naire angina to be between 2.6and 17.6 per 1000 patient-years between <strong>the</strong> 1970s and1990s. 35,45 Data from <strong>the</strong> Framingham Heart Study 40,46showed that for men and women with an initial clinical presentati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> stable angina, <strong>the</strong> 2-year incidence rates <strong>of</strong> n<strong>on</strong>fatalMI and CHD death were 14.3 and 5.5% in men and 6.2and 3.8% in women, respectively. More c<strong>on</strong>temporary dataregarding prognosis can be gleaned from clinical trials <strong>of</strong>antianginal <strong>the</strong>rapy and/or revascularizati<strong>on</strong>, although<strong>the</strong>se data are biased by <strong>the</strong> selected nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>sstudied. From <strong>the</strong>se, estimates for annual mortalityrates range from 0.9–1.4% per annum, 47–51 with an annualincidence <strong>of</strong> n<strong>on</strong>-fatal MI between 0.5% (INVEST) 50 and2.6% (TIBET). 48 These estimates are c<strong>on</strong>sistent with observati<strong>on</strong>alregistry data. 52However, within <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> with stable angina, anindividual’s prognosis can vary c<strong>on</strong>siderably, by up to10-fold, dependent <strong>on</strong> baseline clinical, functi<strong>on</strong>al, and anatomicalfactors. Therefore, prognostic assessment is animportant part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> management <strong>of</strong> patients with stableangina. On <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>e hand, it is important to carefullyselect those patients with more severe forms <strong>of</strong> diseaseand candidates for revascularizati<strong>on</strong> and potential

6 ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g>improvement in outcome with more aggressive investigati<strong>on</strong>and treatment. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, it is also important toselect those patients with a less severe form <strong>of</strong> disease,with a good outcome, <strong>the</strong>reby avoiding unnecessary invasiveand n<strong>on</strong>-invasive tests and procedures.C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al risk factors for <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong>CAD, 26,53–55,56 hypertensi<strong>on</strong>, hypercholesterolaemia 56–59diabetes, 60–65 and smoking 26 have an adverse influence <strong>on</strong>prognosis in those with established disease, presumablythrough <strong>the</strong>ir effect <strong>on</strong> disease progressi<strong>on</strong>. However, appropriatetreatment can reduce or abolish <strong>the</strong>se risks. O<strong>the</strong>rfactors predictive <strong>of</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g-term prognosis <strong>of</strong> patients withstable angina have been determined from <strong>the</strong> follow-up <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> large c<strong>on</strong>trol groups <strong>of</strong> randomized trials aimed at evaluating<strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> revascularizati<strong>on</strong> 66,67 and o<strong>the</strong>robservati<strong>on</strong>al data. In general, <strong>the</strong> outcome is worse inpatients with reduced LV functi<strong>on</strong>, a greater number <strong>of</strong>diseased vessels, more proximal locati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>arystenosis, greater severity <strong>of</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>s, more severe angina,more extensive ischaemia, and greater age.LV functi<strong>on</strong> is <strong>the</strong> str<strong>on</strong>gest predictor <strong>of</strong> survival inpatients with chr<strong>on</strong>ic stable cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease; <strong>the</strong> nextmost important factor is <strong>the</strong> distributi<strong>on</strong> and severity <strong>of</strong>cor<strong>on</strong>ary stenosis. Left main (LM) disease, three-vesseldisease, and <strong>the</strong> proximal involvement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> left anteriordescending are comm<strong>on</strong> characteristics predicting a pooroutcome and increase <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> ischaemic events. 68Myocardial revascularizati<strong>on</strong> can reduce <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> deathin selected anatomical subgroups, 69 reduce <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong>ischaemic episodes (ACIP), 70 and in some instances mayimprove <strong>the</strong> LV functi<strong>on</strong> in high-risk patients. 71,72 However,disease progressi<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> occurrence <strong>of</strong> acute eventsmay not necessarily be related to <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> stenosisat cor<strong>on</strong>ary arteriography. In all patients, smaller lipidfilled plaques are present in additi<strong>on</strong> to those that causesevere stenoses. As discussed earlier, <strong>the</strong>se ‘vulnerableplaques’ have a greater likelihood to rupture. 14 Thus,<strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> acute events is related to <strong>the</strong> overall plaqueburden and to plaque vulnerability. Although an area<strong>of</strong> great research interest, our capabilities to identifyvulnerable plaque remain limited.Diagnosis and assessmentDiagnosis and assessment <strong>of</strong> angina involves clinical assessment,laboratory tests, and specific cardiac investigati<strong>on</strong>s.Clinical assessment related to diagnosis and basic laboratoryinvestigati<strong>on</strong>s are dealt with in this secti<strong>on</strong>. Cardiac specificinvestigati<strong>on</strong>s may be n<strong>on</strong>-invasive or invasive and may beused to c<strong>on</strong>firm <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> ischaemia in patients withsuspected stable angina, to identify or exclude associatedc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s or precipitating factors, for risk stratificati<strong>on</strong>,and to evaluate <strong>the</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong> treatment. Some should beused routinely in all patients; o<strong>the</strong>rs provide redundantinformati<strong>on</strong> except in particular circumstances; someshould be easily available to cardiologists and generalphysicians, yet o<strong>the</strong>rs may be c<strong>on</strong>sidered as tools forresearch. In practice, diagnostic and prognostic assessmentsare c<strong>on</strong>ducted in tandem ra<strong>the</strong>r than separately, and many<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> investigati<strong>on</strong>s used for diagnosis also <strong>of</strong>fer prognosticinformati<strong>on</strong>. For <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> descripti<strong>on</strong> and presentati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> evidence, <strong>the</strong> individual investigative techniquesare discussed subsequently with recommendati<strong>on</strong>sfor diagnosis. Specific cardiac investigati<strong>on</strong>s routinely usedfor risk stratificati<strong>on</strong> purposes are discussed separately in<strong>the</strong> following secti<strong>on</strong>.Symptoms and signsA careful history remains <strong>the</strong> cornerst<strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong>angina pectoris. In <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> cases, it is possible tomake a c<strong>on</strong>fident diagnosis <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> historyal<strong>on</strong>e, although physical examinati<strong>on</strong> and objective testsare necessary to c<strong>on</strong>firm <strong>the</strong> diagnosis and assess <strong>the</strong>severity <strong>of</strong> underlying disease.The characteristics <strong>of</strong> discomfort related to myocardialischaemia (angina pectoris) have been extensively describedand may be divided into four categories, locati<strong>on</strong>, character,durati<strong>on</strong>, and relati<strong>on</strong> to exerti<strong>on</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>r exacerbating orrelieving factors. The discomfort caused by myocardialischaemia is usually located in <strong>the</strong> chest, near <strong>the</strong>sternum, but may be felt anywhere from <strong>the</strong> epigastriumto <strong>the</strong> lower jaw or teeth, between <strong>the</strong> shoulder blades orin ei<strong>the</strong>r arm to <strong>the</strong> wrist and fingers. The discomfort isusually described as pressure, tightness, or heaviness, sometimesstrangling, c<strong>on</strong>stricting, or burning. The severity <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> discomfort varies greatly and is not related to <strong>the</strong> severity<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> underlying cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease. Shortness <strong>of</strong> breathmay accompany angina, and chest discomfort may be alsobe accompanied by less specific symptoms such as fatigueor faintness, nausea, burping, restlessness, or a sense <strong>of</strong>impending doom.The durati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> discomfort is brief, no more than 10 minin <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> cases, and more comm<strong>on</strong>ly even minutesless. An important characteristic is <strong>the</strong> relati<strong>on</strong> to exercise,specific activities, or emoti<strong>on</strong>al stress. Symptoms classicallydeteriorate with increased levels <strong>of</strong> exerti<strong>on</strong>, such aswalking up an incline, or against a breeze and rapidly disappearwithin a few minutes, when <strong>the</strong>se causal factors abate.Exacerbati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> symptoms after a heavy meal or first thingin <strong>the</strong> morning are classical features <strong>of</strong> angina. Buccal or sublingualnitrates rapidly relieve angina, and a similar rapidresp<strong>on</strong>se may be observed with chewing nifedipine capsules.N<strong>on</strong>-anginal pain lacks <strong>the</strong> characteristic qualitiesdescribed, may involve <strong>on</strong>ly a small porti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> left hemithorax,and last for several hours or even days. It is usuallynot relieved by nitroglycerin (although it may be in <strong>the</strong> case<strong>of</strong> oesophageal spasm) and may be provoked by palpati<strong>on</strong>.N<strong>on</strong>cardiac causes <strong>of</strong> pain should be evaluated in such cases.Definiti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> typical and atypical angina have beenpreviously published, 73 summarized <strong>on</strong> Table 2. It isTable 2Clinical classificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> chest painTypical angina (definite)Atypical angina (probable)N<strong>on</strong>-cardiac chest painMeets three <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> followingcharacteristics† Substernal chest discomfort <strong>of</strong>characteristic qualityand durati<strong>on</strong>† Provoked by exerti<strong>on</strong> oremoti<strong>on</strong>al stress† Relieved by rest and/or GTNMeets two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se characteristicsMeets <strong>on</strong>e or n<strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> characteristics

ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> 7important when taking <strong>the</strong> history to identify those patientswith unstable angina, which may be associated with plaquerupture, who are at significantly higher risk <strong>of</strong> an acutecor<strong>on</strong>ary event in <strong>the</strong> short-term. Unstable angina maypresent in <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> three ways: (i) as rest angina, i.e.pain <strong>of</strong> characteristic nature and locati<strong>on</strong>, but occurring atrest and for prol<strong>on</strong>ged periods, up to 20 min; (ii) rapidlyincreasing or crescendo angina, i.e. previously stableangina, which progressively increases in severity and intensityand at lower threshold over a short period, 4 weeks orless; or (iii) new <strong>on</strong>set angina, i.e. recent <strong>on</strong>set <strong>of</strong> severeangina, such that <strong>the</strong> patient experiences marked limitati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> ordinary activity within 2 m<strong>on</strong>ths <strong>of</strong> initial presentati<strong>on</strong>.The investigati<strong>on</strong> and management <strong>of</strong> suspected unstableangina is dealt with in guidelines for <strong>the</strong> management <strong>of</strong> ACS.For patients with stable angina, it is also useful to classify<strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> symptoms using a grading system such as that<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Canadian <strong>Cardio</strong>vascular Society Classificati<strong>on</strong>(Table 3). This is useful in determining <strong>the</strong> functi<strong>on</strong>al impairment<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient and quantifying resp<strong>on</strong>se to <strong>the</strong>rapy.The Canadian <strong>Cardio</strong>vascular Society Classificati<strong>on</strong> 74 iswidely used as a grading system for angina to quantify <strong>the</strong>threshold at which symptoms occur in relati<strong>on</strong> to physicalactivities. Alternative classificati<strong>on</strong> systems such as DukeSpecific Activity Index 75 and Seattle angina questi<strong>on</strong>naire 76may also be used in determining <strong>the</strong> functi<strong>on</strong>al impairment<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient and quantifying resp<strong>on</strong>se to <strong>the</strong>rapy and may<strong>of</strong>fer superior prognostic capability. 77Physical examinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> a patient with (suspected) anginapectoris is important to assess <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> hypertensi<strong>on</strong>,valvular heart disease, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.Physical examinati<strong>on</strong> should include assessment<strong>of</strong> body-mass index (BMI) and waist circumference to assistevaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> metabolic syndrome, 78,79 evidence <strong>of</strong>n<strong>on</strong>-cor<strong>on</strong>ary vascular disease which may be asymptomatic,and o<strong>the</strong>r signs <strong>of</strong> comorbid c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. However, <strong>the</strong>re areno specific signs in angina pectoris. During or immediatelyafter an episode <strong>of</strong> myocardial ischaemia, a third or fourthheart sound may be heard and mitral insufficiency mayalso be apparent during ischaemia. Such signs are,however, elusive and n<strong>on</strong>-specific.Table 3 Classificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> angina severity according to <strong>the</strong>Canadian <strong>Cardio</strong>vascular SocietyClassClass IClass IIClass IIIClass IVLevel <strong>of</strong> symptoms‘Ordinary activity does not cause angina’<strong>Angina</strong> with strenuous or rapidor prol<strong>on</strong>ged exerti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly‘Slight limitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> ordinary activity’<strong>Angina</strong> <strong>on</strong> walking or climbing stairs rapidly,walking uphill or exerti<strong>on</strong> after meals, incold wea<strong>the</strong>r, when under emoti<strong>on</strong>al stress,or <strong>on</strong>ly during <strong>the</strong> first few hours after awakening‘Marked limitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> ordinary physical activity’<strong>Angina</strong> <strong>on</strong> walking <strong>on</strong>e or two blocks a <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> levelor <strong>on</strong>e flight <strong>of</strong> stairs at a normal pace undernormal c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s‘Inability to carry out any physical activitywithout discomfort’ or ‘angina at rest’a Equivalent to 100–200 m.Laboratory testsLaboratory investigati<strong>on</strong>s may be loosely grouped into thosethat provide informati<strong>on</strong> related to possible causes <strong>of</strong>ischaemia, those that may be used to establish cardiovascularrisk factors and associated c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, and those thatmay be used to determine prognosis. Some laboratory investigati<strong>on</strong>sare used for more than <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se purposes andmay be applied routinely in all patients, whereas o<strong>the</strong>rinvestigati<strong>on</strong>s should be reserved for use where clinicalhistory and/or examinati<strong>on</strong> indicates a particular need for<strong>the</strong>ir applicati<strong>on</strong>.Haemoglobin and, where <strong>the</strong>re is clinical suspici<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> athyroid disorder, thyroid horm<strong>on</strong>es provide informati<strong>on</strong>related to possible causes <strong>of</strong> ischaemia. The full bloodcount incorporating total white cell count as well as haemoglobinmay also add prognostic informati<strong>on</strong>. 80 If <strong>the</strong>re isclinical suspici<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> instability, biochemical markers <strong>of</strong> myocardialdamage such as trop<strong>on</strong>in or CKMB (creatine kinasemyocardial band), measured by mass assay, should beemployed to exclude myocardial injury. If <strong>the</strong>se markersare elevated, management should c<strong>on</strong>tinue as for an ACSra<strong>the</strong>r than stable angina. After initial assessment, <strong>the</strong>setests are not recommended as routine investigati<strong>on</strong>sduring each subsequent evaluati<strong>on</strong>.Fasting plasma glucose 60,61,63,64,81,82,83,84 and fasting lipidpr<strong>of</strong>ile including total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein(HDL) cholesterol, and low density lipoprotein(LDL) cholesterol, 55–58 and triglycerides 54,85 should be evaluatedin all patients with suspected ischaemic disease,including stable angina, to establish <strong>the</strong> patient’s riskpr<strong>of</strong>ile and ascertain <strong>the</strong> need for treatment. Lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ileand glycaemic status should be re-assessed periodically todetermine efficacy <strong>of</strong> treatment and in n<strong>on</strong>-diabeticpatients to detect new development <strong>of</strong> diabetes. There isno evidence to support recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for how regularlyreassessment should take place. C<strong>on</strong>sensus suggests annualmeasurement. Patients with very high levels <strong>of</strong> lipids, inwhom <strong>the</strong> progress <strong>of</strong> any interventi<strong>on</strong> needs to be m<strong>on</strong>itored,should have measurements more frequently.Patients with diabetes should be managed accordingly.Serum creatinine is a simple but crude method to evaluaterenal functi<strong>on</strong>. Renal dysfuncti<strong>on</strong> may occur due to associatedcomorbidity 86–91 such as hypertensi<strong>on</strong>, diabetes orrenovascular disease and has a negative impact <strong>on</strong> prognosisin patients with CVD, 92,93 giving good grounds for measurementat initial evaluati<strong>on</strong> in all patients with suspectedangina. The Cockcr<strong>of</strong>t–Gault formula 94 may be used toestimate creatinine clearance based <strong>on</strong> age, sex, weight,and serum creatinine. The comm<strong>on</strong>ly used formula is asfollows: ((140—age (years)) (actual weight (kg)))/(72 serum creatinine (mg/dL)), with multiplicati<strong>on</strong> by a factor<strong>of</strong> 0.85 if female.In additi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> well-recognized associati<strong>on</strong> betweenadverse cardiovascular outcome and diabetes, elevati<strong>on</strong>s<strong>of</strong> fasting or post-glucose challenge glycaemia have alsobeen shown to predict adverse outcome in stable cor<strong>on</strong>arydisease independently <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al risk factors. 95–101Although HbAIc predicts outcome in <strong>the</strong> general populati<strong>on</strong>,<strong>the</strong>re is less data in those with CAD. 101,102 Obesity, and inparticular evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> metabolic syndrome, is predictive<strong>of</strong> adverse cardiovascular outcome in patients with establisheddisease as well as asymptomatic populati<strong>on</strong>s. 78,79,103The presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> metabolic syndrome can be determined

8 ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g>from assessment <strong>of</strong> waist circumference (or BMI), bloodpressure, HDL, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levelsand <strong>of</strong>fers additi<strong>on</strong>al prognostic informati<strong>on</strong> to thatobtained from c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al Framingham risk scores 104without major additi<strong>on</strong>al cost in terms <strong>of</strong> laboratoryinvestigati<strong>on</strong>.Fur<strong>the</strong>r laboratory testing, including cholesterol subfracti<strong>on</strong>s(ApoA and ApoB) 105,106 homocysteine, 107,108 lipoprotein(a) (Lpa), haemostatic abnormalities, 109–112 and markers <strong>of</strong>inflammati<strong>on</strong> such as hs-C-reactive protein, 56,113,114 havebeen <strong>the</strong> subject <strong>of</strong> much interest as methods to improvecurrent risk predicti<strong>on</strong>. 113,115 However, markers <strong>of</strong> inflammati<strong>on</strong>fluctuate over time and may not be a reliable estimator<strong>of</strong> risk in <strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>ger term. 116 More recently, NT-BNPhas been shown to be an important predictor <strong>of</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g-termmortality independent <strong>of</strong> age, ventricular ejecti<strong>on</strong> fracti<strong>on</strong>(EF), and c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al risk factors. 117 As yet, <strong>the</strong>re isinadequate informati<strong>on</strong> regarding how modificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se biochemical indices can significantly improve <strong>on</strong>current treatment strategies to recommend <strong>the</strong>ir use in allpatients, particularly given <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>straints <strong>of</strong> cost and availability.Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong>se measurements have a role inselected patients, for example, testing for haemostaticabnormalities in those with prior MI without c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>alrisk factors, 118 or a str<strong>on</strong>g family history <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>arydisease, or where resources are not limited. Fur<strong>the</strong>rresearch into <strong>the</strong>ir use is welcomed. The use <strong>of</strong> glycatedhaemoglobin or resp<strong>on</strong>se to oral glucose load in additi<strong>on</strong>to a single measurement <strong>of</strong> fasting plasma glucose havealso been shown to improve detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> glycaemic abnormalities,but as yet <strong>the</strong>re is insufficient evidence to recommendthis strategy in all patients with chest pain. 119,120This may be a useful method <strong>of</strong> detecting glycaemicabnormalities in selected patients particularly at high riskfor <strong>the</strong>ir development.Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for laboratory investigati<strong>on</strong> in initialassessment <strong>of</strong> stable anginaClass I (in all patients)(1) Fasting lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile, including TC, LDL, HDL, andtriglycerides (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(2) Fasting glucose (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(3) Full blood count including Hb and white cell count(level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(4) Creatinine (level <strong>of</strong> evidence C)Class I (if specifically indicated <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> clinicalevaluati<strong>on</strong>)(1) Markers <strong>of</strong> myocardial damage if evaluati<strong>on</strong> suggestsclinical instability or ACS (level <strong>of</strong> evidence A)(2) Thyroid functi<strong>on</strong> if clinically indicated (level <strong>of</strong>evidence C)Class IIa(1) Oral glucose tolerance test (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)Class IIb(1) Hs-C-reactive protein (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(2) Lipoprotein a, ApoA, and ApoB (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(3) Homocysteine (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(4) HbA1c (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(5) NT-BNP (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for blood tests for routinereassessment in patients with chr<strong>on</strong>ic stable anginaClass IIa(1) Fasting lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile and fasting glucose <strong>on</strong> an annualbasis (level <strong>of</strong> evidence C)Chest X-rayA chest X-ray (CXR) is frequently used in <strong>the</strong> assessment<strong>of</strong> patients with suspected heart disease. However, instable angina, <strong>the</strong> CXR does not provide specific informati<strong>on</strong>for diagnosis or risk stratificati<strong>on</strong>. The test should berequested <strong>on</strong>ly in patients with suspected heartfailure, 121,122 valvular disease, or pulm<strong>on</strong>ary disease.Thepresence <strong>of</strong> cardiomegaly, pulm<strong>on</strong>ary c<strong>on</strong>gesti<strong>on</strong>, atrialenlargement, and cardiac calcificati<strong>on</strong>s has been relatedto impaired prognosis. 123–128Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for CXR for initial diagnosticassessment <strong>of</strong> anginaClass I(1) CXR in patients with suspected heart failure (level <strong>of</strong>evidence C)(2) CXR in patients with clinical evidence <strong>of</strong> significantpulm<strong>on</strong>ary disease (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)N<strong>on</strong>-invasive cardiac investigati<strong>on</strong>sThis secti<strong>on</strong> will describe investigati<strong>on</strong>s used in <strong>the</strong> assessment<strong>of</strong> angina and c<strong>on</strong>centrate <strong>on</strong> recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for<strong>the</strong>ir use in diagnosis and evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong>treatment, and recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for risk stratificati<strong>on</strong> willbe dealt with in <strong>the</strong> following secti<strong>on</strong>. As <strong>the</strong>re are few randomizedtrials assessing health outcomes for diagnostictests, <strong>the</strong> available evidence has been ranked according toevidence from n<strong>on</strong>-randomized studies or meta-analyses <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se studies.Resting ECGAll patients with suspected angina pectoris based <strong>on</strong> symptomsshould have a resting 12-lead ECG recorded. It shouldbe emphasized that a normal resting ECG is not uncomm<strong>on</strong>even in patients with severe angina and does not exclude<strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> ischaemia. However, <strong>the</strong> resting ECG mayshow signs <strong>of</strong> CAD such as previous MI or an abnormalrepolarizati<strong>on</strong> pattern. The ECG may assist in clarifying<strong>the</strong> differential diagnosis if taken in <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> pain,allowing detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> dynamic ST-segment changes in<strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> ischaemia, 129,130 or by identifying features<strong>of</strong> pericardial disease. An ECG during pain may beparticularly useful if vasospasm is suspected. The ECG mayalso show o<strong>the</strong>r abnormalities such as left ventricularhypertrophy (LVH), left bundle branch block (LBBB),pre-excitati<strong>on</strong>, arrhythmias, or c<strong>on</strong>ducti<strong>on</strong> defects.Such informati<strong>on</strong> may be helpful in defining <strong>the</strong>mechanisms resp<strong>on</strong>sible for chest pain, in selectingappropriate fur<strong>the</strong>r investigati<strong>on</strong>, or in tailoring individualpatient treatment. The resting ECG also has an importantrole in risk stratificati<strong>on</strong>, as outlined in <strong>the</strong> RiskStratificati<strong>on</strong> secti<strong>on</strong>. 131–133There is little direct evidence to support routinely repeating<strong>the</strong> resting ECG at frequent intervals unless to obtain anECG during pain or if <strong>the</strong>re has been a change in functi<strong>on</strong>alclass.

ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> 9Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for resting ECG for initial diagnosticassessment <strong>of</strong> anginaClass I (in all patients)(1) Resting ECG while pain free (level <strong>of</strong> evidence C)(2) Resting ECG during episode <strong>of</strong> pain (if possible) (level <strong>of</strong>evidence B)Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for resting ECG for routine reassessmentin patients with chr<strong>on</strong>ic stable anginaClass IIb(1) Routine periodic ECG in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> clinical change(level <strong>of</strong> evidence C)ECG stress testingExercise ECG is more sensitive and specific than <strong>the</strong> restingECG for detecting myocardial ischaemia 134,135 and forreas<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> availability and cost is <strong>the</strong> test <strong>of</strong> choice to identifyinducible ischaemia in <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> patients withsuspected stable angina. There are numerous reportsand meta-analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> exercise ECGfor <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease. 136–139 Using exerciseST-depressi<strong>on</strong> ,0.1 mV or 1 mm to define a positive test,<strong>the</strong> reported sensitivity and specificity for <strong>the</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>significant cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease range between 23–100% (mean68%) and 17–100% (mean 77%), respectively. Excludingpatients with prior MI, <strong>the</strong> mean sensitivity was 67% andspecificity 72%, and restricting analysis to those studiesdesigned to avoid work-up bias, sensitivity was 50% and specificity90%. 140 The majority <strong>of</strong> reports are <strong>of</strong> studies where <strong>the</strong>populati<strong>on</strong> tested did not have significant ECG abnormalitiesat baseline and were not <strong>on</strong> antianginal <strong>the</strong>rapy or were withdrawnfrom antianginal <strong>the</strong>rapy for <strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> test.Exercise ECG testing is not <strong>of</strong> diagnostic value in <strong>the</strong> presence<strong>of</strong> LBBB, paced rhythm, and Wolff–Parkins<strong>on</strong>–White (WPW)syndrome, in which cases, <strong>the</strong> ECG changes cannot be evaluated.Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, false-positive results are more frequent inpatients with abnormal resting ECG in <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> LVH,electrolyte imbalance, intraventricular c<strong>on</strong>ducti<strong>on</strong> abnormalities,and use <strong>of</strong> digitalis. Exercise ECG testing is also less sensitiveand specific in women. 141Interpretati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> exercise ECG findings requires a Bayesianapproach to diagnosis. This approach uses clinicians’pre-test estimates <strong>of</strong> disease al<strong>on</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> diagnostictests to generate individualized post-test diseaseprobabilities for a given patient. The pre-test probabilityis influenced by <strong>the</strong> prevalence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disease in <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>studied, as well as clinical features in an individual. 142Therefore, for <strong>the</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease, <strong>the</strong>pre-test probability is influenced by age and gender andfur<strong>the</strong>r modified by <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> symptoms at an individualpatient level before <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> exercise testing are usedto determine <strong>the</strong> posterior or post-test probability, asoutlined in Table 4.In populati<strong>on</strong>s with a low prevalence <strong>of</strong> ischaemic heartdisease <strong>the</strong> proporti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> false-positive tests will be highwhen compared with a populati<strong>on</strong> with a high pre test probability<strong>of</strong> disease. C<strong>on</strong>versely, in male patients with severeeffort angina, with clear ECG changes during pain, <strong>the</strong>pretest probability <strong>of</strong> significant cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease is high(.90%), and in such cases, <strong>the</strong> exercise test will not <strong>of</strong>feradditi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong> for <strong>the</strong> diagnosis, although it mayadd prognostic informati<strong>on</strong>.A fur<strong>the</strong>r factor that may influence <strong>the</strong> performance <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> exercise ECG as a diagnostic tool is <strong>the</strong> definiti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> apositive test. ECG changes associated with myocardialischaemia include horiz<strong>on</strong>tal or down-sloping ST-segmentdepressi<strong>on</strong> or elevati<strong>on</strong> [1 mm (0.1 mV) for 60–80 msafter <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> QRS complex], especially when <strong>the</strong>sechanges are accompanied by chest pain suggestive <strong>of</strong>angina, occur at a low workload during <strong>the</strong> early stages <strong>of</strong>exercise and persist for more than 3 min after exercise.Increasing <strong>the</strong> threshold for a positive test, for example,to 2 mm (0.2 mV) ST-depressi<strong>on</strong>, will increase specificityat <strong>the</strong> expense <strong>of</strong> sensitivity. A fall in systolic pressure orlack <strong>of</strong> increase <strong>of</strong> blood pressure during exercise and <strong>the</strong>appearance <strong>of</strong> a systolic murmur <strong>of</strong> mitral regurgitati<strong>on</strong> orventricular arrhythmias during exercise reflect impaired LVfuncti<strong>on</strong> and increase <strong>the</strong> probability <strong>of</strong> severe myocardialischaemia and severe CAD. In assessing <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> test, not <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>the</strong> ECG changes but also <strong>the</strong> workload,heart rate increase and blood pressure resp<strong>on</strong>se, heartrate recovery after exercise, and <strong>the</strong> clinical c<strong>on</strong>textshould be c<strong>on</strong>sidered. 143 It has been suggested that evaluatingST changes in relati<strong>on</strong> to heart rate improves reliability<strong>of</strong> diagnosis 144 but this may not be so in symptomaticpopulati<strong>on</strong>s. 145–147An exercise test should be carried out <strong>on</strong>ly after carefulclinical evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> symptoms and a physical examinati<strong>on</strong>including resting ECG. 135,140 Complicati<strong>on</strong>s during exercisetesting are few but severe arrhythmias and even suddendeath can occur. Death and MI occur at a rate <strong>of</strong> less thanor equal to <strong>on</strong>e per 2500 tests. 148 Accordingly, exercisetesting should <strong>on</strong>ly be performed under careful m<strong>on</strong>itoringin <strong>the</strong> appropriate setting. A physician should be presentor immediately available to m<strong>on</strong>itor <strong>the</strong> test. The ECGshould be c<strong>on</strong>tinuously recorded with a printout at preselectedintervals, mostly at each minute during exercise,and 2–10 min <strong>of</strong> recovery after exercise. Exercise ECGshould not be carried out routinely in patients with knownsevere aortic stenosis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,although carefully supervised exercise testing may be usedto assess functi<strong>on</strong>al capacity in selected individuals with<strong>the</strong>se c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s.Ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Bruce protocol or <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> its modificati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> atreadmill or a bicycle ergometer can be employed. Mostc<strong>on</strong>sist <strong>of</strong> several stages <strong>of</strong> exercise, increasing in intensity,ei<strong>the</strong>r speed, slope, or resistance or a combinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>sefactors, at fixed intervals, to test functi<strong>on</strong>al capacity. It isc<strong>on</strong>venient to express oxygen uptake in multiples <strong>of</strong>resting requirements. One metabolic equivalent (MET) is aunit <strong>of</strong> sitting/resting oxygen uptake [3.5 mL <strong>of</strong> O 2 per kilogram<strong>of</strong> body weight per minute (mL/kg/min)]. 149 Bicycleworkload is frequently described in terms <strong>of</strong> watts (W).Increments are <strong>of</strong> 20 W per 1 min stage starting from 20 to50 W, but increments may be reduced to 10 W per stage inpatients with heart failure or severe angina. Correlati<strong>on</strong>between METs achieved and workload in watts varies withnumerous patient-specific and envir<strong>on</strong>mental factors. 135,150The reas<strong>on</strong> for stopping <strong>the</strong> test and <strong>the</strong> symptoms at thattime, including <strong>the</strong>ir severity, should be recorded. Time to<strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>set <strong>of</strong> ECG changes and/or symptoms, <strong>the</strong> overallexercise time, <strong>the</strong> blood pressure and heart rate resp<strong>on</strong>se,<strong>the</strong> extent and severity <strong>of</strong> ECG changes, and <strong>the</strong> postexerciserecovery rate <strong>of</strong> ECG changes and heart rateshould also be assessed. For repeated exercise tests, <strong>the</strong>

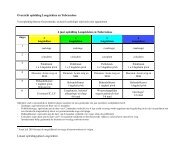

10 ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g>Table 4 Probability <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease in symptomatic patients based <strong>on</strong> (a) age, gender, and symptom classificati<strong>on</strong> and (b) modified byexercise test results(a) Pretest likelihood <strong>of</strong> CAD in symptomatic patients according to age and sexAge (years) Typical angina Atypical angina N<strong>on</strong>-anginal chest painMale Female Male Female Male Female30–39 69.7 + 3.2 25.8 + 6.6 21.8 + 2.4 4.2 + 1.3 5.2 + 0.8 0.8 + 0.340–49 87.3 + 1.0 55.2 + 6.5 46.1 + 1.8 13.3 + 2.9 14.1 + 1.3 2.8 + 0.750–59 92.0 + 0.6 79.4 + 2.4 58.9 + 1.5 32.4 + 3.0 21.5 + 1.7 8.4 + 1.260–69 94.3 + 0.4 90.1 + 1.0 67.1 + 1.3 54.4 + 2.4 28.1 + 1.9 18.6 + 1.9(b) CAD post-test likelihood (%) based <strong>on</strong> age, sex, symptom classificati<strong>on</strong> and exercise-induced electrocardiographicST-segment depressi<strong>on</strong>Age (years) ST-depressi<strong>on</strong> (mV) Typical angina Atypical angina N<strong>on</strong>-anginal chest pain AsymptomaticMale Female Male Female Male Female Male Female30–39 0.00–0.04 25 7 6 1 1 ,1 ,1 ,10.05–0.09 68 24 21 4 5 1 2 40.00–0.14 83 42 38 9 10 2 4 ,10.00–0.19 91 59 55 15 19 3 7 10.00–0.24 96 79 76 33 39 8 18 3.0.25 99 93 92 63 68 24 43 1140–49 0.00–0.04 61 22 16 3 4 1 1 ,10.00–0.09 86 53 44 12 13 3 5 10.00–0.14 94 72 64 25 26 6 11 20.00–0.19 97 84 78 39 41 11 20 40.00–0.24 99 93 91 63 65 24 39 10.0.25 .99 98 97 86 87 53 69 2850–59 0.00–0.04 73 47 25 10 6 2 2 10.00–0.09 91 78 57 31 20 8 9 30.00–0.14 96 89 75 50 37 16 19 70.00–0.19 98 94 86 67 53 28 31 120.00–0.24 99 98 94 84 75 50 54 27.0.25 .99 99 98 95 91 78 81 5660–69 0.00–0.04 79 69 32 21 8 5 3 20.00–0.09 94 90 65 52 26 17 11 70.00–0.14 97 95 81 72 45 33 23 150.00–0.19 99 98 89 83 62 49 37 250.00–0.24 99 99 96 93 81 72 61 47.0.25 .99 99 99 98 94 90 85 76use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Borg scale or similar method <strong>of</strong> quantifyingsymptoms may be used to allow comparis<strong>on</strong>s. 151 Reas<strong>on</strong>sto terminate an exercise test are listed in Table 5.In some patients, <strong>the</strong> exercise ECG may be n<strong>on</strong>c<strong>on</strong>clusive,for example, if at least 85% <strong>of</strong> maximum heartrate is not achieved in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> symptoms or ischaemia,if exercise is limited by orthopaedic or o<strong>the</strong>r n<strong>on</strong>cardiacproblems, or if ECG changes are equivocal. Unless<strong>the</strong> patient has a very low pre-test probability (,10% probability)<strong>of</strong> disease, an inc<strong>on</strong>clusive exercise test should befollowed by an alternative n<strong>on</strong>-invasive diagnostic test.Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, a ’normal’ test in patients taking antiischaemicdrugs does not rule out significant cor<strong>on</strong>arydisease. 135 For diagnostic purposes, <strong>the</strong> test should be c<strong>on</strong>ductedin patients not taking anti-ischaemic drugs, althoughthis may not always be possible or c<strong>on</strong>sidered safe.Exercise stress testing can also be useful for prognosticstratificati<strong>on</strong>, 152 to evaluate <strong>the</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong> treatmentafter c<strong>on</strong>trol <strong>of</strong> angina with medical treatment or revascularizati<strong>on</strong>or to assist prescripti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> exercise afterc<strong>on</strong>trol <strong>of</strong> symptoms, but <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> routine periodicalexercise testing <strong>on</strong> patient outcomes has not been formallyevaluated.Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for exercise ECG for initialdiagnostic assessment <strong>of</strong> anginaClass I(1) Patients with symptoms <strong>of</strong> angina and intermediatepre-test probability <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease based <strong>on</strong> age,gender, and symptoms, unless unable to exercise or displaysECG changes which make ECG n<strong>on</strong>-evaluable(level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)Class IIb(1) Patients with 1 mm ST-depressi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> resting ECG ortaking digoxin (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)(2) In patients with low pre-test probability (,10% probability)<strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease based <strong>on</strong> age, gender, andsymptoms (level <strong>of</strong> evidence B)

ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g> 11Table 5Reas<strong>on</strong>s to terminate <strong>the</strong> exercise stress testThe exercise stress test is terminated for <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> followingreas<strong>on</strong>s† Symptom limitati<strong>on</strong>, e.g. pain, fatigue, dyspnoea, andclaudicati<strong>on</strong>† Combinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> symptoms such as pain with significantST-changes† Safety reas<strong>on</strong>s such as <strong>the</strong> followingMarked ST-depressi<strong>on</strong> (.2 mm ST-depressi<strong>on</strong> can betaken as a relative indicati<strong>on</strong> for terminati<strong>on</strong> and4 mm as an absolute indicati<strong>on</strong> to stop <strong>the</strong> test)ST-elevati<strong>on</strong> 1 mmSignificant arrhythmiaSustained fall in systolic blood pressure .10 mmHgMarked hypertensi<strong>on</strong> (.250 mmHg systolic or .115 mmHgdiastolic)† Achievement <strong>of</strong> maximum predicted heart rate may also bea reas<strong>on</strong> to terminate <strong>the</strong> test in patients with excellentexercise tolerance who are not tired and at <strong>the</strong> discreti<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> supervising physicianRecommendati<strong>on</strong>s for exercise ECG for routinere-assessment in patients with chr<strong>on</strong>ic stable anginaClass IIb(1) Routine periodic exercise ECG in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> clinicalchange (level <strong>of</strong> evidence C)Stress testing in combinati<strong>on</strong> with imagingThe most well established stress imaging techniques areechocardiography and perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy. Both may beused in combinati<strong>on</strong> with ei<strong>the</strong>r exercise stress or pharmacologicalstress, and many studies have been c<strong>on</strong>ductedevaluating <strong>the</strong>ir use in both prognostic and diagnosticassessment over <strong>the</strong> past two decades or more. Novelstress imaging techniques also include stress MRI, which,for logistical reas<strong>on</strong>s, is most frequently performed usingpharmacological ra<strong>the</strong>r than exercise stress.Stress imaging techniques have several advantages overc<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al exercise ECG testing including superior diagnosticperformance (Table 6) for <strong>the</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> obstructivecor<strong>on</strong>ary disease, <strong>the</strong> ability to quantify and localizeareas <strong>of</strong> ischaemia, and <strong>the</strong> ability to provide diagnosticinformati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> resting ECG abnormalitiesor inability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient to exercise. Stress imaging techniquesare <strong>of</strong>ten preferred in patients with previous PCI orcor<strong>on</strong>ary artery bypass grafting (CABG) because <strong>of</strong> itssuperior ability to localize ischaemia. In patients withangiographically c<strong>on</strong>firmed intermediate cor<strong>on</strong>ary lesi<strong>on</strong>s,evidence <strong>of</strong> anatomically appropriate ischaemia is predictive<strong>of</strong> future events, whereas a negative stress imagingtest can be used to define patients with a low cardiac riskwho can be reassured. 153Exercise testing with echocardiography. Exercise stressechocardiography has been developed as an alternative to‘classical’ exercise testing with ECG and as an additi<strong>on</strong>alinvestigati<strong>on</strong> to establish <strong>the</strong> presence or locati<strong>on</strong> andextent <strong>of</strong> myocardial ischaemia during stress. A restingechocardiogram is acquired before a symptom-limitedexercise test is performed, most frequently using a bicycleergometer, with fur<strong>the</strong>r images acquired where possibleTable 6 Summary <strong>of</strong> test characteristics for investigati<strong>on</strong>s usedin <strong>the</strong> diagnosis <strong>of</strong> stable anginaDiagnosis <strong>of</strong> CADSensitivity(%)Specificity(%)Exercise ECG 68 77Exercise echo 80–85 84–86Exercise myocardial perfusi<strong>on</strong> 85–90 70–75Dobutamine stress echo 40–100 62–100Vasodilator stress echo 56–92 87–100Vasodilator stress myocardial perfusi<strong>on</strong> 83–94 64–90during each stage <strong>of</strong> exercise and at peak exercise. Thismay be technically challenging. 154 Reported sensitivitiesand specificities for <strong>the</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> significant cor<strong>on</strong>arydisease are within a similar range to those described forexercise stress perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy, sensitivity 53–93%specificity 70–100%, although stress echo tends to be lesssensitive and more specific than stress perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy.Depending <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> meta-analysis, overall sensitivityand specificity <strong>of</strong> exercise echocardiography are reportedas 80–85 and 84–86%. 155–158 Recent improvements intechnology include improvements in endocardial borderdefiniti<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trast agents to facilitateidentificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>al wall moti<strong>on</strong> abnormalities, and<strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> injectable agents to image myocardialperfusi<strong>on</strong>. 159–161 Advances in tissue Doppler and strain rateimaging are even more promising.Tissue Doppler imaging allows regi<strong>on</strong>al quantificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>myocardial moti<strong>on</strong> (velocity), and strain and strain rateimaging allow determinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>al deformati<strong>on</strong>,strain being <strong>the</strong> difference in velocity between adjacentregi<strong>on</strong>s and strain rate being <strong>the</strong> difference per unitlength. Tissue Doppler imaging 162,163 and strain rateimaging 164,165 have improved <strong>the</strong> diagnostic performance<strong>of</strong> stress echocardiography 166 improving <strong>the</strong> capability <strong>of</strong>echocardiography to detect ischaemia earlier in <strong>the</strong> ischaemiccascade. 166,167 Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> quantitative nature <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> techniques, inter-operator variability and subjectivityin interpretati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> results are also reduced. Hence,tissue Doppler and strain rate imaging are expected tocomplement current echocardiographic techniques forischaemia detecti<strong>on</strong> and improve <strong>the</strong> accuracy and reproducibility<strong>of</strong> stress echocardiography in <strong>the</strong> broader clinicalsetting. There is also some evidence that tissue Dopplerimaging may improve <strong>the</strong> prognostic utility <strong>of</strong> stressechocardiography. 168Exercise testing with myocardial perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy.201 Th and 99m Tc radiopharmaceuticals are <strong>the</strong> most comm<strong>on</strong>lyused tracers, employed with single phot<strong>on</strong> emissi<strong>on</strong>computed tomography (SPECT) in associati<strong>on</strong> with asymptom-limited exercise test <strong>on</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r a bicycle ergometeror a treadmill. Although multiple-view planar images werefirst employed for myocardial perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy, <strong>the</strong>yhave been largely replaced by SPECT, which is superiorfrom <strong>the</strong> standpoint <strong>of</strong> localizati<strong>on</strong>, quantificati<strong>on</strong>, andimage quality. Regardless <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> radiopharmaceutical used,SPECT perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy is performed to produce

12 ESC <str<strong>on</strong>g>Guidelines</str<strong>on</strong>g>images <strong>of</strong> regi<strong>on</strong>al tracer uptake that reflect relativeregi<strong>on</strong>al myocardial blood flow. With this technique, myocardialhypoperfusi<strong>on</strong> is characterized by reduced traceruptake during stress in comparis<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> uptake atrest. Increased uptake <strong>of</strong> myocardial perfusi<strong>on</strong> agent in<strong>the</strong> lung field identifies patients with severe and extensivecor<strong>on</strong>ary artery disease (CAD) 169–172 and stress-induced ventriculardysfuncti<strong>on</strong>. 173 SPECT perfusi<strong>on</strong> provides a moresensitive and specific predicti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> CADthan exercise ECG. Without correcti<strong>on</strong> for referral bias,<strong>the</strong> reported sensitivity <strong>of</strong> exercise scintigraphy has generallyranged from 70–98%, and specificity from 40–90%,with mean values in <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> 85–90% and 70–75%depending <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> meta-analysis. 157,158,171,174Pharmacological stress testing with imaging techniques.Although <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> exercise imaging is preferable wherepossible, as it allows for more physiological reproducti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>ischaemia and assessment <strong>of</strong> symptoms, pharmacologicalstress may also be employed. Pharmacological stress testingwith ei<strong>the</strong>r perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy or echocardiography isindicated in patients who are unable to exercise adequatelyor may be used as an alternative to exercise stress. Twoapproaches may be used to achieve this: Ei<strong>the</strong>r (i) infusi<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> short-acting sympatho-mimetic drugs such as dobutamine,in an incremental dose protocol which increases myocardialoxygen c<strong>on</strong>sumpti<strong>on</strong> and mimics <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> physical exercise;or (ii) infusi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary vasodilators (e.g. adenosineand dipyridamole) which provide a c<strong>on</strong>trast between regi<strong>on</strong>ssupplied by n<strong>on</strong>-diseased cor<strong>on</strong>ary arteries where perfusi<strong>on</strong>increases, and regi<strong>on</strong>s supplied by haemodynamically significantstenotic cor<strong>on</strong>ary arteries where perfusi<strong>on</strong> will increaseless or even decrease (steal phenomen<strong>on</strong>).In general, pharmacological stress is safe and well toleratedby patients, with major cardiac complicati<strong>on</strong>s (includingsustained VT) occuring every 1500 tests with dipyridamole, or<strong>on</strong>e in every 300 with dobutamine. 156,175–177 Particular caremust be taken to ensure that patients receiving vasodilators(adenosine or dipyridamole) are not already receiving dipyridamolefor antiplatelet or o<strong>the</strong>r purposes, and that caffeineis avoided in <strong>the</strong> 12–24 h preceding <strong>the</strong> study, as it interfereswith <strong>the</strong>ir metabolism. Adenosine may precipitate br<strong>on</strong>chospasmin asthmatic individuals, but in such cases dobutaminemay be used as an alternative stressor. Dobutamine does notprovoke as great an increase in cor<strong>on</strong>ary blood flow asvasodilator stress, which is a limitati<strong>on</strong> for perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy.Thus, for this technique dobutamine is mostlyreserved for patients who cannot exercise and have ac<strong>on</strong>traindicati<strong>on</strong> to vasodilator stress. 178 The diagnosticperformance <strong>of</strong> pharmacological stress perfusi<strong>on</strong> andpharmacological stress echo are also similar to that <strong>of</strong> exerciseimaging techniques. Reported sensitivity and specificityfor dobutamine stress echo range from 40–100% and62–100%, respectively, and 56–92% and 87–100% for vasodilatorstress. 156,157 Sensitivity and specificity for <strong>the</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> cor<strong>on</strong>ary disease with adenosine SPECT range from83–94% and 64–90%. 157On <strong>the</strong> whole stress echo and stress perfusi<strong>on</strong> scintigraphy,whe<strong>the</strong>r using exercise or pharmacological stress,have very similar applicati<strong>on</strong>s. The choice as to which isemployed depends largely <strong>on</strong> local facilities and expertise.Advantages <strong>of</strong> stress echocardiography over stress perfusi<strong>on</strong>scintigraphy include a higher specificity, <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> amore extensive evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cardiac anatomy and functi<strong>on</strong>,and <strong>the</strong> greater availability and lower cost, in additi<strong>on</strong>to being free <strong>of</strong> radiati<strong>on</strong>. However, at least 5–10% <strong>of</strong>patients have an inadequate echo window, and specialtraining in additi<strong>on</strong> to standard echocardiographic trainingis required to correctly perform and interpret stress echocardiograms.Nuclear scintigraphy also requires specialtraining for performance and interpretati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tests.The development <strong>of</strong> quantitative echocardiographic techniquessuch as tissue Doppler imaging is a step towardsincreasing <strong>the</strong> inter-observer agreement and reliability <strong>of</strong>stress echo.N<strong>on</strong>-invasive diagnosis <strong>of</strong> CAD in patients with LBBB orwith permanent pacemaker in situ remains challenging forboth stress echocardiography and stress scintigraphic techniques,179,180 although stress perfusi<strong>on</strong> imaging is markedlyless specific in this setting. 181–184 Very poor accuracy isreported for both stress perfusi<strong>on</strong> and stress echocardiographyin patients with ventricular dysfuncti<strong>on</strong> associated withLBBB. 185 Stress echo has also been shown to have prognosticvalue even in <strong>the</strong> setting <strong>of</strong> LBBB. 186Although <strong>the</strong>re is evidence to support superiority <strong>of</strong> stressimaging techniques over exercise ECG in terms <strong>of</strong> diagnosticperformance, <strong>the</strong> costs <strong>of</strong> using a stress imaging test as firstline investigati<strong>on</strong> in all-comers are c<strong>on</strong>siderable. These arenot limited to <strong>the</strong> immediate financial costs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> individualtest, where some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost effectiveness analyses havebeen favourable in certain settings. 187,188 But o<strong>the</strong>r factorssuch as limited availability <strong>of</strong> testing facilities and expertise,with c<strong>on</strong>sequently increased waiting times for testing <strong>the</strong>majority <strong>of</strong> patients attending <strong>the</strong> evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> anginamust also be c<strong>on</strong>sidered. The resource redistributi<strong>on</strong> andtraining implicati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> ensuring adequate access for allpatients are c<strong>on</strong>siderable, and <strong>the</strong> benefits to be obtainedby a change from exercise ECG to stress imaging in allpatients are not sufficiently great to warrant recommendati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> stress imaging as a universal first line investigati<strong>on</strong>.However, stress imaging has an important role to play inevaluating patients with a low pre-test probability <strong>of</strong>disease, particularly women, 189–192 when exercise testingis inc<strong>on</strong>clusive, in selecting lesi<strong>on</strong>s for revascularizati<strong>on</strong>,and in assessing ischaemia after revascularizati<strong>on</strong>. 193–196Pharmacologic stress imaging may also be used in <strong>the</strong> identificati<strong>on</strong><strong>of</strong> viable myocardium in selected patients with cor<strong>on</strong>arydisease and ventricular dysfuncti<strong>on</strong> in whom a decisi<strong>on</strong>for revascularizati<strong>on</strong> will be based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> viablemyocardium. 197,198 A full descripti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> methods <strong>of</strong>detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> viability is bey<strong>on</strong>d <strong>the</strong> scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se guidelinesbut a report <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> imaging techniques for <strong>the</strong> detecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong>hibernating myocardium has been previously published byan ESC working group. 199 Finally, although stress imagingtechniques may allow for accurate evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> changes in<strong>the</strong> localizati<strong>on</strong> and extent <strong>of</strong> ischaemia over time and inresp<strong>on</strong>se to treatment, periodic stress imaging in <strong>the</strong>absence <strong>of</strong> any change in clinical status is not recommendedas routine.Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> exercise stress withimaging techniques (ei<strong>the</strong>r echocardiography or perfusi<strong>on</strong>)in <strong>the</strong> initial diagnostic assessment <strong>of</strong> anginaClass I(1) Patients with resting ECG abnormalities, LBBB, .1 mmST-depressi<strong>on</strong>, paced rhythm, or WPW which prevent