Proceedings of the Untangled symposium: - WSPA

Proceedings of the Untangled symposium: - WSPA

Proceedings of the Untangled symposium: - WSPA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

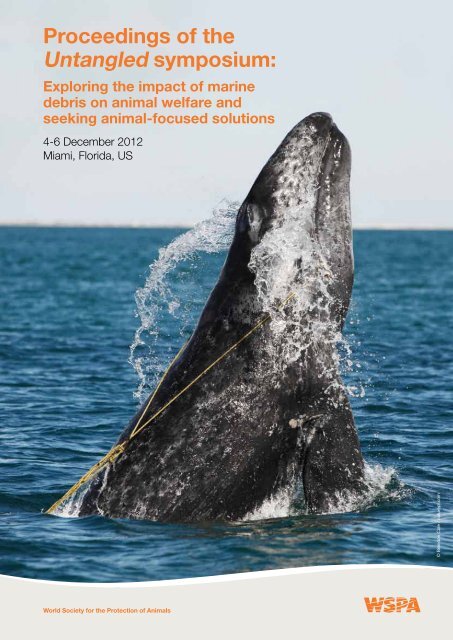

<strong>Proceedings</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Untangled</strong> <strong>symposium</strong>:Exploring <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> marinedebris on animal welfare andseeking animal-focused solutions4-6 December 2012Miami, Florida, US© Brandon Cole / naturepl.comWorld Society for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Animals

At <strong>the</strong> World Society for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Animals (<strong>WSPA</strong>),we have protected animals around <strong>the</strong> globe for more than 30 years.We use our collective skills and knowledge to move individuals,organisations and governments to transform animals’ lives. Our diversework includes ending <strong>the</strong> mass suffering <strong>of</strong> industrially farmed animals,preventing <strong>the</strong> pain <strong>of</strong> individual animals caught up in disasters,and making rabies-driven dog culls history by proving that a humaneresponse works best for animals and people.Working in more than 50 countries, we create positive change byexposing cruelty and pioneering sustainable solutions to animal suffering.We also act for animals at a global level, using our consultative status at<strong>the</strong> United Nations to make sure our message is heard: that <strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong>animals are inextricably linked to our own, and now more than ever is <strong>the</strong>time to stop <strong>the</strong>ir suffering.Suggested citation: World Society for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Animals.(2013). <strong>Proceedings</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Untangled</strong> <strong>symposium</strong>: Exploring <strong>the</strong>impact <strong>of</strong> marine debris on animal welfare and seeking animalfocusedsolutions. London: <strong>WSPA</strong>.

Contents1. Preface 52. Executive summary 63. Overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Untangled</strong> sessions 84. Summary <strong>of</strong> problem and 9solution workshop outcomesFishing gear 9Packaging/consumer debris 10Animal rescue/disentanglement 125. Acknowledgements 13Annex 1: <strong>Untangled</strong> Declaration 15Annex 2: Priority problems and solutions 16Table 1: Communication exercise – 23key messages and target audiencesAnnex 3: Knowledge gaps 25Annex 4: Submitted abstracts 30accompanying poster presentationsAnnex 5: Delegate contact details 61

1Preface<strong>Untangled</strong> was <strong>the</strong> first ever global <strong>symposium</strong> dedicatedto identifying <strong>the</strong> major problems that marine debrispresents to <strong>the</strong> welfare <strong>of</strong> animals and to seekinganimal-focused solutions. Held from 4-6 December2012 at <strong>the</strong> Marriott Biscayne Bay hotel in Miami,Florida, <strong>the</strong> <strong>symposium</strong> was organised and hosted by<strong>the</strong> World Society for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Animals (<strong>WSPA</strong>)with <strong>the</strong> support and endorsement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United NationsEnvironment Programme (UNEP). <strong>Untangled</strong> wasattended by over 60 experts from 20 countries, includingparticipants from governments, inter-governmentalorganisations, non-pr<strong>of</strong>it organisations, academiaand <strong>the</strong> fishing and plastics industries.These proceedings include: a summary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> topic,event and top level conclusions; an overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>sessions; an outline <strong>of</strong> workshop outcomes anddiscussions; and speakers’ abstracts. This documentintends to provide delegates and o<strong>the</strong>r interested partieswith details <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> analysis which took place at <strong>the</strong><strong>symposium</strong> in order to identify <strong>the</strong> key animal welfareproblems caused by marine debris, and which alloweddelegates to share and explore some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mostpractical and positive solutions to <strong>the</strong>se problems.<strong>WSPA</strong> wishes to thank all <strong>symposium</strong> delegates for<strong>the</strong>ir attendance, <strong>the</strong>ir enthusiasm and for contributing<strong>the</strong>ir valuable knowledge and expertise to create aproductive and successful action-orientated event.One <strong>of</strong> <strong>WSPA</strong>’s primary objectives in hosting <strong>Untangled</strong>was to understand and prioritise <strong>the</strong> animal-focusedproblems <strong>of</strong>, and solutions to, marine debris in orderto inform plans for a new campaign on this issue, andthis objective was certainly achieved. It is <strong>WSPA</strong>’s hopeand belief that <strong>the</strong> event and <strong>the</strong>se proceedings willalso prove useful for delegates and o<strong>the</strong>r stakeholdersinvolved in tackling <strong>the</strong> complex global problem <strong>of</strong>marine debris, and seeking to protect <strong>the</strong> animalsaffected by it.5

2Executive summaryThe issueMarine debris (also known as marine litter) is a trulyglobal problem gaining increasing attention and concernaround <strong>the</strong> world. Perhaps more commonly described asan environmental issue, <strong>the</strong> littering <strong>of</strong> our oceans alsohas disastrous consequences for <strong>the</strong> individual animalsliving <strong>the</strong>re, debilitating, mutilating and killing millions <strong>of</strong>birds, whales, dolphins, turtles and o<strong>the</strong>r marine wildlifeevery year.Defined by <strong>the</strong> Honolulu Strategy as ‘any anthropogenic,manufactured, or processed solid material (regardless<strong>of</strong> size) discarded, disposed <strong>of</strong>, or abandoned thatends up in <strong>the</strong> marine environment’ 1 , marine debriscan describe items as small as micro-plastic granulesor as large as shipping containers. From <strong>the</strong> scientificand grey literature summarised in <strong>WSPA</strong>’s <strong>Untangled</strong>report (2012), it is clear that certain types <strong>of</strong> marinedebris cause significant welfare problems for marineanimals. Fishing rope, nets and line, packing bandsand straps and plastic packaging can all entangleanimals, causing a range <strong>of</strong> problems including injuryand restricted movement and reduced feeding ability.These problems may persist for months or even years,in many cases eventually causing death due to infection,drowning or starvation. O<strong>the</strong>r types <strong>of</strong> litter, suchas plastic bags and cigarette lighters, are ingested,suffocating animals, preventing <strong>the</strong>m from feedingand causing internal injuries. This animal suffering issignificant, large-scale and avoidable.<strong>WSPA</strong> is developing a global campaign which aims tomake <strong>the</strong> oceans a safer home for animals – one in which<strong>the</strong>y are no longer at risk <strong>of</strong> being killed or injured byour dangerous debris. At a time when <strong>the</strong> environmentalimpacts <strong>of</strong> marine debris are gaining increasing globalinterest, <strong>WSPA</strong> believes it is also important to bringanimal welfare to <strong>the</strong> forefront <strong>of</strong> solution-focuseddiscussions. This goal was a primary motivation behindholding <strong>the</strong> <strong>symposium</strong>, providing its <strong>the</strong>me.1 A global framework for <strong>the</strong> prevention and management <strong>of</strong> marine debris,United Nations Environment Programme and National Oceanic andAtmospheric Administration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States. http://5imdc.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/honolulustrategy.pdf(accessed February 2013).The <strong>symposium</strong><strong>Untangled</strong> brought toge<strong>the</strong>r over 60 experts from a range<strong>of</strong> backgrounds. The rich diversity <strong>of</strong> delegates meantthat knowledge and experience was shared acrossregions, cultures and sectors, resulting in an impressivedegree <strong>of</strong> information exchange from many perspectives.The <strong>symposium</strong> hosted posters and ‘lightning talk’presentations by 40 experts. The talks highlighted veryclearly <strong>the</strong> magnitude, global scope and complexities<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> marine debris problem and <strong>the</strong> threat it poses to<strong>the</strong> welfare <strong>of</strong> animals. Through presentations under <strong>the</strong><strong>the</strong>mes <strong>of</strong> (1) reducing debris, (2) removing debris and(3) rescuing animals caught in debris, delegates learnedabout <strong>the</strong> animal welfare impacts <strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong>marine debris and <strong>the</strong> solutions being implemented insome parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world.In group sessions delegates were able to define priorityproblems (Annex 2), focusing on fishing-related debris,consumer/packaging-related debris, and rescue efforts.In fur<strong>the</strong>r group sessions delegates <strong>the</strong>n discussedand presented solutions (Annex 2), many <strong>of</strong> whichwere based on effective work already underway insome countries. Delegates with a scientific backgroundensured that discussions were scientifically robust,while delegates working at a policy level were able tohighlight <strong>the</strong> challenges presented by implementingpolicy changes on such a complex issue, but were alsoable to provide examples <strong>of</strong> policy changes already inplace and case studies <strong>of</strong> success. Representatives <strong>of</strong>key industries such as plastics and fishing were ableto convey both positive and realistic feedback to some<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> solutions that were suggested, as well as sharesome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> solutions that <strong>the</strong>se industries are alreadysupporting. Delegates with rescue response experienceshared <strong>the</strong> unique challenges <strong>the</strong>y face, some practicaland pragmatic solutions and <strong>the</strong> successes that <strong>the</strong>yhave had.Delegates approached <strong>the</strong> workshops and discussionswith optimism and energy, united by a sense <strong>of</strong> hopethat with co-ordinated action this problem can be solved.While knowledge gaps exist for some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues<strong>the</strong>re was a clear determination that <strong>the</strong> internationalcommunity and all relevant stakeholders must takeresponsibility and urgent action. Some common <strong>the</strong>meswere apparent throughout all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues discussed,including <strong>the</strong> need for greater political and industry6

2Executive summarycommitment on a global scale, increased co-ordinationbetween stakeholders, successful prevention/mitigation/rescue strategies to be implemented more widely,and better/more appropriate regulations, legislationand protocols to be put in place. Although delegatescame from diverse backgrounds, <strong>the</strong>re was a sharedrecognition that <strong>the</strong> animal welfare impacts <strong>of</strong> marinedebris are an issue <strong>of</strong> significance and importance. Acommitment to take action was demonstrated by <strong>the</strong>signing <strong>of</strong> a declaration (Annex 1).Key outcomes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Untangled</strong> <strong>symposium</strong>:1. The <strong>Untangled</strong> Declaration (Annex 1)2. Identification and clear definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> priority animalwelfare problems caused by marine debris (Annex 2)3. Proposed innovative and practical solutions for each<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> priority animal welfare problems caused bymarine debris (Annex 2)4. Suggested key messages for communicating <strong>the</strong>priority problems to identified stakeholders andpersuading <strong>the</strong>m to action <strong>the</strong> proposed solutions(Table 1)5. Identification <strong>of</strong> existing knowledge gaps that shouldbe addressed to enable effective delivery <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>proposed solutions (Annex 3).7

3Overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Untangled</strong> sessionsThe <strong>symposium</strong> was opened by Lyndall Stein, <strong>WSPA</strong>International Director <strong>of</strong> Campaigns, and Claire Bass,<strong>WSPA</strong> Oceans Campaign Leader, who welcomedand thanked delegates before providing an overview<strong>of</strong> <strong>WSPA</strong>’s interest and involvement in <strong>the</strong> globalmarine debris problem from an organisationalperspective, and set <strong>the</strong> animal welfare context for<strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>symposium</strong>.Vincent Sweeney <strong>of</strong> UNEP delivered an inspiringkeynote speech, providing <strong>the</strong> international context <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> problem and an overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work that UNEPis currently involved in, including <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>ir Global Partnership for Marine Litter (GPML). Laterin <strong>the</strong> evening, participants were treated to an upliftingpresentation from Holly Lohuis, Director <strong>of</strong> Jean-MichelCousteau’s Ocean Futures Society.During <strong>the</strong> first morning, presentations were structuredaround three solution-based <strong>the</strong>mes:• Reducing <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> entangling or animal-harmingdebris entering <strong>the</strong> marine environment• Removing marine debris which is already in <strong>the</strong> marineenvironment• Rescuing <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> animals already entangled inor affected by marine debris.During <strong>the</strong>se concurrent group sessions, 40 participantsgave poster presentations based on <strong>the</strong> above <strong>the</strong>mes,highlighting <strong>the</strong> animal welfare problems causedby marine debris in different parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong>challenges faced in solving <strong>the</strong>m, and examples <strong>of</strong>solution-orientated research and work. It was clear from<strong>the</strong>se sessions and <strong>the</strong> accompanying abstracts (Annex4) that <strong>the</strong>re are a significant number <strong>of</strong> organisationsand agencies, <strong>of</strong> all sizes, working hard to address <strong>the</strong>marine debris issue.Delegates were <strong>the</strong>n split again into three differentgroups, reflecting <strong>the</strong> two main types <strong>of</strong> debris in <strong>the</strong>marine environment that cause problems for animals and<strong>the</strong> need to respond to, and rescue, animals which havealready been affected by it:• Fishing gear – abandoned, lost or discardedfishing gear•Packaging/consumer litter – any form <strong>of</strong> packagingor consumer litter which ends up in <strong>the</strong> marineenvironment and causes animal welfare problems• Animal rescue/disentanglement – <strong>the</strong> actions <strong>of</strong>detecting, responding and rescuing animals injuredor entangled in any form <strong>of</strong> marine debris.Within <strong>the</strong>se groups delegates formed sub-groups andtook part in facilitated discussions to identify and definewhat <strong>the</strong>y felt were <strong>the</strong> priority animal welfare problemscaused by marine debris (Annex 2). Having defined <strong>the</strong>problems, <strong>the</strong> same sub-groups were asked to identifyappropriate and viable solutions to <strong>the</strong>se problems(Annex 2), including which key stakeholders would beresponsible and need to be involved, and <strong>the</strong> challengesthat would be encountered.A plenary session was convened to allow each groupto report back to <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>symposium</strong> delegates,giving an overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir prioritised problems andsolutions. Delegates in <strong>the</strong> audience were asked toplace <strong>the</strong>mselves in <strong>the</strong> mind-set <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> identified keystakeholders and ask questions to constructively critique<strong>the</strong> proposed solutions. The presentations promptedlively discussion, with many important points beingraised and relevant information exchanged by all.On <strong>the</strong> final day <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>symposium</strong> all delegatesattended a plenary session in which <strong>the</strong>y were taskedwith identifying key knowledge gaps that exist inrelation to <strong>the</strong> solutions that had been identified in <strong>the</strong>previous sessions. This resulted in a summary account<strong>of</strong> what is known and what is not, including suggestionsfor where missing knowledge might be obtained.Subsequently, a session on communication was heldin which <strong>the</strong> discussion focused on how key messagesabout <strong>the</strong> marine debris problem and its solutionscould be communicated effectively to differentaudiences. Delegates <strong>the</strong>n split into smaller groups,each tasked with a particular marine debris problem/solution and a stakeholder for whom <strong>the</strong>y had toidentify key messages.At <strong>the</strong> close <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>symposium</strong>, delegates stated <strong>the</strong>irshared concern for <strong>the</strong> animal welfare problems causedby marine debris and a commitment to take action bysigning up to a declaration which had been drafted by asmall group <strong>of</strong> delegates, from different sectors, over <strong>the</strong>three days (Annex 1).8

4Summary <strong>of</strong> problem and solutionworkshop outcomesFishing gearAbandoned, lost or discarded fishing nets, particularlygill/drift nets, were identified as a priority problemrequiring urgent action due to <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problems<strong>the</strong>y cause for animals (i.e. number <strong>of</strong> animals affected)and <strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong> injuries <strong>the</strong>y cause. Excess pot traps thatare lost and indiscriminately entrap or entangle wildlifewere also identified as a significant problem.A global ban on gill nets was proposed as <strong>the</strong> ultimatesolution to <strong>the</strong> problem, although <strong>the</strong> substantialchallenges that would arise in trying to achieve this banwere acknowledged. Despite <strong>the</strong>se challenges, many feltthat given <strong>the</strong> significant difference a ban would make,it was worth aiming for. The United Nations has banneddrift nets in international waters (although this ban is<strong>of</strong>ten circumvented) and <strong>the</strong>re are also moves by somenational governments, such as Argentina, to ban <strong>the</strong>recreational use <strong>of</strong> gill nets in <strong>the</strong>ir own territorial waters,meaning <strong>the</strong>re are precedents that could be built upon.A key source <strong>of</strong> concern is that <strong>the</strong>re are currently norealistic alternatives to gill nets and a ban is not likelyto stop people from using <strong>the</strong>m due to <strong>the</strong>ir efficacyfor catching fish. It was acknowledged that <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong>enforcement required to maintain <strong>the</strong> ban would be highall over <strong>the</strong> world.O<strong>the</strong>r solutions focused on a variety <strong>of</strong> means toenable and incentivise fishermen 2 to safely dispose<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir nets on land (for example, an increase in portwaste disposal and recycling facilities for nets) andintroducing better technology to make nets less likely toharm marine animals. Innovative solutions around <strong>the</strong>recovery <strong>of</strong> ‘ghost nets’ were put forward, emulatingschemes in places such as Norway, South Korea andHawaii where regular trawls take place to retrieve lostor discarded nets. The potential to recycle ‘end <strong>of</strong> life’nets (ei<strong>the</strong>r disposed <strong>of</strong> in dedicated port waste facilitiesor recovered from <strong>the</strong> sea via trawls) into energy oro<strong>the</strong>r materials was agreed to be a compelling factorin creating both economic and green incentives for netrecycling schemes.A lot <strong>of</strong> discussion was held about <strong>the</strong> potentialchallenges <strong>of</strong> implementing different types <strong>of</strong> incentiveschemes to prevent fishermen discarding <strong>the</strong>ir nets,in particular <strong>the</strong> fact that it may be difficult to securegovernment funding in many countries, althoughcorporate sponsorship may play a role in this solution.It was emphasised that it would be unlikely to be a ‘onesize fits all’ approach as solutions would have to becatered to <strong>the</strong> particular markets and circumstancesin different countries. One suggestion was that it couldbe a fisheries-driven process, using a governmentadministrated‘pay to play’ system, linking <strong>the</strong> cost<strong>of</strong> a license and possible rebates to a fisherman’s abilityto demonstrate that s/he has maintained <strong>the</strong>ir gear ingood condition. Within this system penalties wouldbe incurred for <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> gear. The situation forartisanal fishers would need to be looked at in greatdetail as in many cases <strong>the</strong>y are unlikely to be able toafford to pay extra fees and in such cases <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong>net ‘buy-back’ schemes was discussed as a potentialway <strong>of</strong> encouraging fishermen to maintain gear in agood state <strong>of</strong> repair, ra<strong>the</strong>r than using it until it fallsapart and is lost.With regard to traps, discussion centred on existing newtechnologies that can help make traps less <strong>of</strong> a danger tomarine animals; <strong>the</strong>se ranged from traps that require onlyone line to traps that have rings or panels that degradeafter a period <strong>of</strong> time. The use <strong>of</strong> stiffened line was alsodiscussed and it was noted that this only reduces welfareproblems for some species; it would for example notprevent all whale entanglements. Regulatory measuresto reduce fishing effort with particular regard to <strong>the</strong>number <strong>of</strong> traps that are set each year were alsodefined as necessary.2In this document <strong>the</strong> term ‘fishermen’ will be used to refer to people <strong>of</strong>both genders who fish ei<strong>the</strong>r commercially or recreationally.9

4Summary <strong>of</strong> problem and solutionworkshop outcomesPackaging/consumer debrisThis group identified that many countries lack basicwaste infrastructure, legislation and education, resultingin waste/debris entering <strong>the</strong> marine environment. Fourkey debris types were identified as priority problemscausing severe suffering to animals: plastic bags;plastic packing bands; plastic six-pack rings andplastic bottle caps.Solutions were quite specific to each debris type,but all required industry and consumer buy-in andsome additionally needed policy changes to introduceparticular legislation.There was discussion about whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> ultimate aimshould be <strong>the</strong> responsible disposal <strong>of</strong> plastic and o<strong>the</strong>rdebris or a substantial reduction <strong>of</strong> plastic use by societyoverall. Industry representatives in <strong>the</strong> group felt that itwas much more realistic to find disposal and recyclingfocusedsolutions, while o<strong>the</strong>rs emphasised that thisshould still go hand in hand with an effort to encouragepeople to live a less consumerist lifestyle and reduce oreliminate certain types <strong>of</strong> packaging altoge<strong>the</strong>r.Although plastic was clearly identified as a cause <strong>of</strong>many animal welfare problems in <strong>the</strong> oceans, it wasacknowledged that alternative materials <strong>of</strong>ten comewith <strong>the</strong>ir own set <strong>of</strong> problems (i.e. o<strong>the</strong>r environmentalimpacts, unsustainable sources etc.).There was considerable positive discussion aboutinitiatives to reduce or ban plastic bags, especially asthis is an issue that both <strong>the</strong> public and retailers arealready increasingly aware <strong>of</strong>. Examples were provided<strong>of</strong> countries, regions and cities banning plastic bagsaltoge<strong>the</strong>r whereas in o<strong>the</strong>rs a tax on <strong>the</strong> bags isimposed at <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> sale. Many delegates felt thatsuch initiatives can and should be replicated on a globalscale. Several important lessons have been learnedfrom existing schemes such as <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> initialsuccess in reducing plastic bag use by charging a feecan plateau; and in order to prevent this <strong>the</strong> fee needs toincrease incrementally over time. Although governmentshave a responsibility to enforce and administer legislationthat restricts or bans plastic bags, this has proven, atleast in some places, to be low cost compared to what<strong>the</strong>y have had to pay previously to clean up <strong>the</strong>ir waterways <strong>of</strong> plastic bags. One delegate reported that inIreland, where plastic bags have been banned, fishermenhave reported that <strong>the</strong>y no longer ‘catch’ plastic bagsin <strong>the</strong>ir nets, compared to Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Irish waters where<strong>the</strong>re is a very apparent problem – evidence that bansreally do reduce <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se items in <strong>the</strong>marine environment.The six-pack ring problem and solution discussion raisedcomments about how <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> packaginghas been reduced or even eliminated in some places,meaning it would not be a relevant issue to focus on inevery country.10

4Summary <strong>of</strong> problem and solutionworkshop outcomesSolutions which engaged industry in a positive way,such as <strong>the</strong> ‘Coca Cola Cap Challenge’ and ‘CorporateCoastline’, were generally viewed as potentiallyvery good initiatives with great public engagementopportunities. Some people questioned whe<strong>the</strong>r childrenare still interested in collecting things like bottle caps, but<strong>the</strong>re were also suggestions <strong>of</strong> ways to make <strong>the</strong>m morecollectable, such as putting a marine-related fact on <strong>the</strong>inside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bottle cap. It was mentioned that companiessuch as Apple, Schweppes and Shell have sponsoredbeaches and conducted beach clean-ups which <strong>the</strong>ypaid for <strong>the</strong>mselves (a model which could be replicated),and that <strong>the</strong> US-based Adopt a Highway initiative couldalso be used as a model given that it is a similar idea.Hotels situated on coastlines could also be asked toprovide funds for beach clean-ups.The group positively reviewed a campaign idea inwhich users <strong>of</strong> plastic packing bands are asked tocut <strong>the</strong>m after use via a ‘Cut if you Care’ logo printedon each band by <strong>the</strong> manufacturer. It would cost <strong>the</strong>manufacturers money to print on <strong>the</strong> band but in return<strong>the</strong>ir CSR reputation would be improved. The groupnoted that <strong>the</strong> message would ei<strong>the</strong>r need to be printedin different languages or be represented by symbolsto make it language neutral. It was highlighted thatan educational campaign focused on <strong>the</strong> problemsassociated with packing bands would need to runalongside <strong>the</strong> messaging that appeared on <strong>the</strong>bands <strong>the</strong>mselves.11

4Summary <strong>of</strong> problem and solutionworkshop outcomesAnimal rescue/disentanglementThe problems prioritised by <strong>the</strong> rescue groups werepredominantly centred on <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> capacity that <strong>the</strong>existing rescue community has, as a whole, to respondto animals affected by marine litter. Rescue networks donot exist in all areas where <strong>the</strong>y are needed and where<strong>the</strong>y do exist, people likely to come into contact wi<strong>the</strong>ntangled animals do not always know about <strong>the</strong>m orhow to contact <strong>the</strong>m. Legislation was also raised as anissue – ei<strong>the</strong>r a lack <strong>of</strong> it or too much <strong>of</strong> it in some caseswhich hampers rescue attempts.Solutions were focused on building <strong>the</strong> capacity <strong>of</strong>existing networks, both in terms <strong>of</strong> increasing <strong>the</strong> number<strong>of</strong> people actively working to respond to entanglementcases in parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world where it is needed, and also interms <strong>of</strong> introducing internationally agreed best practice/protocols to improve <strong>the</strong> efficiency <strong>of</strong> rescue efforts andprotect both animal and human welfare.During <strong>the</strong> plenary discussion delegates queried how <strong>the</strong>capacity-building <strong>of</strong> rescue networks would be funded,emphasising that it probably is not high priority for mostgovernments. Examples that can be used as persuasivecase studies were given, such as <strong>the</strong> successfulgovernment-funded whale disentanglement networksand training in <strong>the</strong> US. It was acknowledged that bestpractice for whale disentanglement already exists andwork at <strong>the</strong> International Whaling Commission (IWC)and within <strong>the</strong> US government is building upon this andtraining is starting to become available in o<strong>the</strong>r countries.However, for o<strong>the</strong>r species it was apparent that <strong>the</strong>re isa lack <strong>of</strong> agreed best practice and that a standing expertgroup would be beneficial in this regard. It is unfortunatethat <strong>the</strong>re is no intergovernmental body that focuses on<strong>the</strong> welfare <strong>of</strong> marine animals aside from whales (coveredby <strong>the</strong> IWC) as <strong>the</strong> involvement <strong>of</strong> a relevant IGO wouldbe useful in establishing and disseminating best practicefor disentanglement and rescue.12

5Acknowledgements<strong>WSPA</strong> would like to thank and acknowledge <strong>the</strong> followingpeople: all delegates who attended <strong>the</strong> <strong>Untangled</strong><strong>symposium</strong> and all those who submitted abstracts ando<strong>the</strong>r information relevant to <strong>the</strong> event; Andy Butterworthand Isabella Clegg, author and co-author <strong>of</strong> <strong>WSPA</strong>’s<strong>Untangled</strong> report; and Bernard Ross, Alice Hopkinsonand Alex Hamlin from The Management Centre for <strong>the</strong>irexcellent facilitation.13

Annex 1<strong>Untangled</strong> DeclarationWe are all concerned that marine litter is increasinglypolluting our oceans and killing millions <strong>of</strong> animalsevery year. Animals are ingesting and becomingentangled in debris originating from fisheries andconsumer-related waste, such as plastic packaging.These animals may suffer, sometimes for longperiods, and can experience painful deaths.Recognising our shared responsibility to protectanimals from unnecessary suffering, we urgeour governments, industry, intergovernmentalbodies and agencies, and <strong>the</strong> public worldwide,to commit to actions to: prevent our dangerouswaste, including that derived from fishing gear, fromreaching <strong>the</strong> oceans; to remove that which is already<strong>the</strong>re; and to rescue those animals caught in itsdeadly grip.In tackling <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> marine litter we all committo take action to protect marine animals fromneedless suffering.15

Annex 2Priority problems and solutionsSolution 3: A global ban on gill nets.• Target stakeholders: UN; governments• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): would save millions <strong>of</strong> animalsworldwide – decreased by-catch and marine debrisrelatedanimal suffering; level <strong>the</strong> playing field forall fishermen worldwide; would protect endangeredspecies (conservation incentive); increased health <strong>of</strong>global ocean ecosystem• Challenges: would have to be done globally so <strong>the</strong>reis no advantage to those who continue to use gillnets; huge economic impact on fisheries and fishingcommunities; lack <strong>of</strong> political will; impact on foodsupply and no alternative food sources in some areas;fishing industry revolt; lack <strong>of</strong> alternatives to gill nets;insufficient organisation <strong>of</strong> multiple stakeholders;financial resources to fight this fight; historical andcultural barriers• Time frame: 20 years.Packaging/consumer litterProblem 1: Single-use carrier bags (whe<strong>the</strong>rintentionally or accidently improperly disposed<strong>of</strong> by consumers) enter <strong>the</strong> waterways and oceanswhere <strong>the</strong>y are ingested by marine mammalsand turtles, causing gut blockage and internalcomplications resulting in decreased health <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> animal and/or death.Solution: Local to centralised governments impose afee for single-use plastic bags which would discourageexcessive use by retailers and consumers.• Target stakeholders: central government (municipal/state/federal)• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): revenue generated by <strong>the</strong>fee could subsidise government funded clean-up<strong>of</strong> waterways; compensate retailers for programmeparticipation; once in place this policy will make anear-immediate impact; good precedents are already inplace in some places, i.e. Washington DC – where <strong>the</strong>bag fee has raised $2 million towards cleaning up <strong>the</strong>river and a significant reduction in plastic bag waste;success in Maryland has been aided by consumers’ability to identify with <strong>the</strong> piece <strong>of</strong> water aimed at beingcleaned up; an analysis could be done to show <strong>the</strong>economic benefits <strong>of</strong> reduced use; increased marketing<strong>of</strong> reusable bags would get <strong>the</strong>se companies on side• Challenges: ingrained consumer behaviour/convenience lifestyle; lack <strong>of</strong> political will; resistancefrom plastics industry; easier to pass this legislation insome areas than in o<strong>the</strong>rs• Time frame: 1-2 years to introduce and pass legislation;1 year to require retailer compliance.18

Annex 2Priority problems and solutionsProblem 2: Plastic packing bands used by industrythat enter <strong>the</strong> marine ecosystem and threatento entangle marine animals including pinnipeds,cetaceans, turtles and large fish.Solution: ‘Cut after Use’, ‘Cut if you Care’campaigns – printing a logo/slogan on packingbands that highlights <strong>the</strong> need to <strong>the</strong> cut <strong>the</strong>bands prior to disposal.• Target stakeholders: fishing industry and o<strong>the</strong>r users<strong>of</strong> packing bands• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): better corporate image forcompanies who invest in printing <strong>the</strong> logo/slogan;consumers can be made aware that taking thissimple action will result in a tangible positive impacton animalsProblem 3: Plastic six-pack rings used for beveragecontainers may end up in oceans when ei<strong>the</strong>rintentionally or accidently improperly disposed <strong>of</strong>by consumers, injuring or strangling marine wildlife,causing suffering and/or death.Solution: Motivate consumers and retailers to collectand recycle six-pack rings at <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> sale to helplocal causes.• Target stakeholders: retailers and consumers• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): ‘recycling for a reason’(i.e. providing a strong motivator) will reduce <strong>the</strong>number <strong>of</strong> injuries to and incidences <strong>of</strong> strangling<strong>of</strong> sea-birds, turtles and fish by six-pack rings.• Challenges: will not work without industry involvementand investment.19

Annex 2Priority problems and solutionsProblem 4: Bottle caps and rings that end up in <strong>the</strong>marine environment can potentially cause digestionproblems when swallowed by animals, as well asresulting in death and toxin transfer fur<strong>the</strong>r up <strong>the</strong>food chain.Solution 1: ‘(Coca Cola) Cap Challenge’ – for everycap collected, industry would donate $X, so that fiftyper cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> funds goes to <strong>the</strong> school for educationalor sporting supplies and fifty per cent goes to aninternational NGO for marine animal welfare.• Target stakeholders: industry, educators and students• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): a fun and global collectioncompetition to increase recycling; caps could becomea ‘cool’ collectable item for kids; possible to makethis viral, using social media, idea <strong>of</strong> competition viaschool/community/country tallies or a competitionto use caps creatively – geographical mapping usingonline tools; CSR appeals to industry, a way to getindustry name in schools; some similar programmesalready exist (proven to be popular, potential partners)• Challenges: dependent on <strong>the</strong> appropriate corporatesupport; some kind <strong>of</strong> infrastructure will need to bein place to recycle <strong>the</strong> caps so need alignment wi<strong>the</strong>xisting operations or need to invest in new ones;some similar programmes already exist (not novel);demonstrating <strong>the</strong> scale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> animal welfare impact <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se items is difficult (i.e. requires data demonstratingconsumption <strong>of</strong> caps by animals)• Time frame: consideration would be around initial smallscale pilot project <strong>the</strong>n roll out globallySolution 3: ‘Keep Caps On’ – build upon North AmericanTrade Association efforts to strongly encourage recyclingfacilities to accept and adopt technology to properlyrecycle caps with bottles, so that consumers can placeboth in <strong>the</strong> recycling bins, and so reduce <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong>bottle caps littered.• Target stakeholders: recycling companies• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): NATA project already beingimplemented – industry is recognising that caps needto be recycled; can cut top <strong>of</strong>f bottle and ring quicklyand easily with new technology; caps are one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>most highly littered items• Challenges: value <strong>of</strong> plastic caps is not as high as<strong>the</strong> bottle.Solution 4: Extended producer responsibilityprogramme: building on <strong>the</strong> UNEP/NOAA HonoluluStrategy, governments could regulate industry to pay for<strong>the</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> litter products, change design <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>seproducts, or improve <strong>the</strong> existing bottle bill legislation toinclude caps, so that less are littered.• Target stakeholders: governments and o<strong>the</strong>r policymakers; industry• Challenges: requires companies to pay a fee for <strong>the</strong>collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir material and improved recyclingefforts – may not be popular with industry so <strong>the</strong>ymay try and block it; not all areas will implement thiskind <strong>of</strong> regulation.Solution 2: ‘Corporate Coastline’ – Corporationswould sponsor or adopt beaches/sections <strong>of</strong> coastlineglobally so that <strong>the</strong>y take pride in and responsibility for<strong>the</strong>m, engaging <strong>the</strong>ir staff to work with local communitiesto keep <strong>the</strong> area clean and free <strong>of</strong> bottle caps (and o<strong>the</strong>rdebris, e.g. nets).20

Annex 2Priority problems and solutionsAnimal rescue/disentanglementProblem 1: A lack <strong>of</strong> capacity in terms <strong>of</strong> training,infrastructure, responder networks and monitoringin <strong>the</strong> rescue community is hampering animalwelfare efforts.Solution 1: An international animal welfare NGO tocreate a standing expert group to develop, monitor andshare international protocols describing best practice inrescue training, infrastructure and evaluation with keyinfluential governments and relevant inter-governmentalorganisations, lobbying for <strong>of</strong>ficial adoption <strong>of</strong> bestpracticeprotocols into law. These protocols could alsobe disseminated to stakeholders and would enable aneffective approach to <strong>the</strong> successful rescue <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong>entangled marine animals around <strong>the</strong> world.• Target stakeholders: key influential governments andIGOs, i.e. US government, EU, CMS, IWC, UNEP, etc.Solution 3: The existing regional networks will identify,recruit and train new potential rescue organisations toincrease <strong>the</strong> coverage and <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> entangledanimals that can be detected and saved.• Target stakeholders: rescue organisations that arewilling and able to participate• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): <strong>the</strong> greater number <strong>of</strong> entangledanimals that could be detected and saved by having awider network• Challenges: regional networks not yet established at allin some places• Time frame: 2 years.• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): public opinion demandingeffective response to entangled wildlife; majority/influential government positions that o<strong>the</strong>r governmentsare likely to follow; case studies that demonstrate <strong>the</strong>protocols work• Challenges: competing priority issues; funds requiredto set up working groups within IGOs; lack <strong>of</strong> anexisting IGO with a remit for all marine wildlife andanimal welfare; conservation and development focusra<strong>the</strong>r than animal welfare• Time frame: 2-3 years.Solution 2: An international animal welfare NGO shouldestablish an expert group to identify best practice fortraining, infrastructure and monitoring.• Target stakeholders: an international animalwelfare NGO• Motivation (<strong>of</strong> targets): current lack <strong>of</strong>, and need for, aninternational cohesive and fully informed standardisedresponse to entangled animals• Challenges: competition between rescue groups,conflicting priorities, lack <strong>of</strong> funds to bringpeople toge<strong>the</strong>r• Time frame: 1 year.21

Annex 2Priority problems and solutionsProblem 2: A lack <strong>of</strong> adequate protocol infrastructureand knowledge to enable fishermen, coastalcommunities, workers and o<strong>the</strong>r ocean users totell <strong>the</strong> people equipped to take action about anentangled animal requiring rescue.Solution 1: Better awareness and understanding <strong>of</strong>marine animals and <strong>the</strong>ir role in <strong>the</strong> fisheries ecosystemwill better motivate fishermen to report incidences <strong>of</strong>marine animal entanglement.Solution 2: Joint initiatives linking detectors andresponders – perhaps mediated by NGOs and/or research organisations – will improve <strong>the</strong> trustrelationship and mutual benefit to all parties involved.Solution 3: The existence and awareness <strong>of</strong> a globalnetwork for reporting and monitoring marine animalrescue needs would increase <strong>the</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> respondersto reach more animals requiring rescue at <strong>the</strong> local andregional level, and would increase public engagementand motivation on <strong>the</strong> issue.Solution 4: Best practice for successful detection,response and rescue should be shared morewidely and effectively between government agenciesand responders.• Target stakeholders: agencies directly involved inanimal rescue/disentanglement, possibly academics• Time frame: 3 years.Problem 3: Marine animal rescues can becomplicated by a lack <strong>of</strong> efficient, appropriate andeffective government engagements (regulation/legislation etc.).Solution 1: To motivate governments to changelegislation with <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> improving response toentangled animals. An international animal welfare NGO(or a working group <strong>of</strong> several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m) should provide areview <strong>of</strong> current response/rescues. This would provideexamples <strong>of</strong> good and bad practice and compliance.Solution 2: In order to ensure human safety andanimal welfare in response efforts to entangled marineanimals, UNEP, FAO, IWC, CMS and o<strong>the</strong>r internationalgovernment entities should encourage member states tocreate effective regulations by convening a task force at<strong>the</strong>ir next meeting to review best practice (human safetyand animal welfare should be <strong>the</strong> guiding priorities ingovernment regulation).Solution 3: Country X should create legislation for <strong>the</strong>safe and effective rescue <strong>of</strong> entangled whales by seekingadvice and capacity building from international experts.This would demonstrate leadership on a regional issueand recognition <strong>of</strong> animal welfare as a topic <strong>of</strong> growingglobal concern.Solution 4: The US (or o<strong>the</strong>r countries where laws areimpeding or compromising effective response) shouldreview and modify outdated existing regulations whichprevent <strong>the</strong> effective response to entangled seals (oro<strong>the</strong>r species where relevant).22

Table 1Communication exercise – key messagesand target audiencesPriority problem Stakeholder Key messages to communicate Method/s Actions to ask <strong>the</strong>m to takeSingle-use carrier bags (whe<strong>the</strong>rintentionally or accidentlyimproperly disposed <strong>of</strong> byconsumers) enter <strong>the</strong> waterwaysand oceans where <strong>the</strong>y areingested by marine mammalsand turtles, causing gut blockageand internal complicationsresulting in decreased health <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> animal and/or deathPlastic packing bands usedby industry that enter <strong>the</strong>marine ecosystem and threatento entangle marine animalsincluding pinnipeds, cetaceans,turtles and large fishA lack <strong>of</strong> capacity in terms <strong>of</strong>training, infrastructure, respondernetworks and monitoring in <strong>the</strong>rescue community is hamperinganimal welfare effortsA lack <strong>of</strong> adequate protocolinfrastructure and knowledgeto enable fishermen, coastalcommunities, workers ando<strong>the</strong>r ocean users to tell <strong>the</strong>people equipped to take actionabout an entangled animalrequiring rescueA ten-yearoldPlasticindustryThegovernment<strong>of</strong>ficialConsumerGarbage in <strong>the</strong> oceans killsmillions <strong>of</strong> animals. The numberone item is plastic bags. Yourparents use plastic bags – this iskilling turtlesAre you aware <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problem?Are <strong>the</strong>re any advancesin technology to minimise<strong>the</strong> problem?Ensure that <strong>the</strong> problemstatement is stated at‘consumer level’The economic impact,e.g. tourismNegative impact for human/animal lifeMarine animals becomeentangled in debris and fishinggear and people that find <strong>the</strong>mdo not know what to do/ whoto informIn some places <strong>the</strong>re is no oneto call even though <strong>the</strong>re arean increasing number <strong>of</strong> rescuegroups around <strong>the</strong> worldThere needs to be more publicityabout problems and solutionsFace-to-faceconversationsEstablishingconstructivedialogue andrelationshipProtocols/facts/statisticsCase studieson <strong>the</strong> negativeimpactsCreate socialmedia network(Twitter,Facebook etc.)to inform public• It is really easy to fix this:Just say no! (in <strong>the</strong> shop)• Plastic bags become futuregarbage – let’s stop thistoge<strong>the</strong>r• Find out whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> industrybelieves any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> potentialsuggested solutions are viable• Find out what <strong>the</strong> barriers areto overcome from <strong>the</strong> industryperspective• Establish whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>company would be interestedin participating in extendedproducer responsibility• Set regulations• Set <strong>the</strong> local protocols• Organise <strong>the</strong> strandingnetworks• Funding <strong>the</strong> preventativeprogrammes• Establish a select committee• Benchmarks to highlightsuccess• Local participation andawarenessYou can help by finding out whatis being done locally and who isin chargeHuman safetyMarine animal rescues canbe complicated by a lack<strong>of</strong> efficient, appropriateand effective governmentengagements (regulation/legislation etc.)Thegovernment<strong>of</strong>ficialProvide solutionsto <strong>the</strong> problemsPlan programmesfor <strong>the</strong>m• Protocol/monitoring• Facilities• Enforcement agencies• Training and capacity-building• Institutional legislature24

Annex 3Knowledge gapsDelegates were provided with a random selection<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> prioritised problems and proposed solutionsand asked to think about (1) what knowledge we, asan international community, already have to enableus to tackle this problem and (2) what necessaryinformation is unknown and who/where <strong>the</strong> sources<strong>of</strong> this kind <strong>of</strong> information might be.Problem: Ghost fishing nets are responsible for <strong>the</strong>entanglement <strong>of</strong> unacceptably large numbers <strong>of</strong>marine animals.Solution: Governments and fishing industry to cometoge<strong>the</strong>r to develop a regulatory framework based oneconomic incentives to reduce gear loss to decreaseunintended entanglement/mortality <strong>of</strong> wildlife.What do we know?• Nets get lost in marine environment, both intentionallyand accidently – causing entanglement• Nets can be re-used (for o<strong>the</strong>r purposes) or recycled• Locally illegal but no enforcement• Broad range <strong>of</strong> species affected• Countries are opposed to regulationsWhat is unknown?• How much is lost?• How long do <strong>the</strong>se ghost nets ‘keep fishing’• Where in <strong>the</strong> world are <strong>the</strong> biggest problems?• What would prevent intentional disposal• Baseline data – monitoringWho knows it?• Fishing industry• Gear technology manufacturers• Coastal clean-up people• Enforcement agencies/governmentsWho might know?• Fishing community• Scientific community• Some government agencies• Some NGOs• Net owners (identification)Problem: Excess traps are used at a number <strong>of</strong>fisheries across <strong>the</strong> globe. Millions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se trapsare lost at sea every year and continue to fishindiscriminately for periods <strong>of</strong> months to years.They entangle and suffocate marine wildlifeincluding turtles and seabirds.Solution: Reduce <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> derelict traps byreducing <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> traps used.What do we know?• Impacts many species <strong>of</strong> animal on a global scale• Some key geographic locations• Trap limits exist in some areas• Effects <strong>of</strong> habitat on trap loss• There is local awareness <strong>of</strong> issue in some areasWhat is unknown?• Numbers <strong>of</strong> traps• How to prevent traps being lost• Impact on animal populations (conservation issues)• Long term datasets• Level <strong>of</strong> fisherman engagement – likely success• Relationship between number <strong>of</strong> pots used and <strong>the</strong>number lost• Mechanisms <strong>of</strong> entanglement• Level <strong>of</strong> reporting and enforcement• What species• Economic impact• What <strong>the</strong> best alternative technology available isWho knows it?• Fishermen, scientists, specialists• UK – IFCA• Some government agencies• Some NGOs• Development agenciesWho might know?• Fishermen, public, divers• Scientists• Government – fishing authorities• Fishing community• Some NGOs• Maritime authorities• Modellers, marine biologists• Trap manufacturers25

Annex 3Knowledge gapsProblem: A lack <strong>of</strong> capacity in terms <strong>of</strong> training,infrastructure, responder networks and monitoringin <strong>the</strong> rescue community is hampering animalwelfare efforts.Solution: An international animal welfare NGO shouldcreate a standing expert group to develop, monitor andshare international protocols describing best practice inrescue training, infrastructure and evaluation with keyinfluential governments and relevant intergovernmentalorganisations, lobbying for <strong>of</strong>ficial adoption <strong>of</strong> bestpracticeprotocols into law. These protocols could alsobe disseminated to stakeholders and would enable aneffective approach to <strong>the</strong> successful rescue <strong>of</strong> entangledmarine animals around <strong>the</strong> world.What do we know?• Local protocols exist• Protocols exist for whales• There is a lack <strong>of</strong> authority for this in some locationsWhat is unknown?• Who <strong>the</strong> key influential governments are• Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re is a key international veterinary organisation whocould endorse protocols once <strong>the</strong>y exist• Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re are any suitable coordinating bodies• What an expert panel should consist <strong>of</strong> and who shouldbe on it. Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re should be an expert panel per speciesor per group• Whe<strong>the</strong>r it is possible to create a best practice for all species• Euthanasia options for all species• Where <strong>the</strong> areas <strong>of</strong> greatest need are, and where lacks a rescuenetwork that needs one• Whe<strong>the</strong>r it is better to have localised best practice as opposedto globalWho knows it?• Response and rescue networks, BDMLR (UK), MARK (UK)• Law enforcement agencies• Marine Mammal Conservancy• Marine Mammal Stranding Network• IWC (whales)• Sea Turtles Restoration ProjectWho might know?• Existing rescue organisations/networks• Coast-guards• Veterinary associations may be able to advise on euthanasia• Local rescue organisations and networks should be able toadvise on <strong>the</strong>ir local conditionsProblem: A lack <strong>of</strong> adequate protocol, infrastructureand knowledge to enable fishermen, coastalcommunities, workers and o<strong>the</strong>r ocean users totell <strong>the</strong> people equipped to take action about anentangled animal requiring rescue.Solution: Best practice for successful detection,response and rescue should be shared more widelyand more effectively between government agenciesand responders.What do we know?• New and existing protocols• Contact details/numbers if an entangled animal is seen – insome places• That we need a no-blame culture on this issue• In water, humans risk deathWhat is unknown?• Who else is willing and able to participate• Reporting methods – not everyone has access to telephones• Unknown scale <strong>of</strong> entanglement over <strong>the</strong> world• What different protocols exist in different parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world• Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> existing protocols are <strong>the</strong> sameWho knows it?• NOAA, IWC, CWT, MSN (UK)• NOAA, PCCS, FWC, Coast Guard, NSRI, BDMLR, ONDB• Fishing representatives• New partners in <strong>the</strong> developing world, e.g. Brazil,<strong>the</strong> Philippines• UNEPWho might know?• Existing rescue networks• Stranding networks/databases: NOAA; Environment Agency(Argentina); SAWDN (South Africa)• Probably isn’t known without a review process28

Annex 3Knowledge gapsProblem: Marine animal rescues can becomplicated by a lack <strong>of</strong> efficient, appropriateand effective government engagements(regulation/legislation etc.).Solution: To motivate governments to change legislationwith <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> improving response to entangled animals.An international animal welfare NGO (or a working group<strong>of</strong> several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m) should provide a review <strong>of</strong> currentresponse/rescues. This would provide examples <strong>of</strong> goodand bad practice and compliance.What do we know?• Lack <strong>of</strong> regulation through to too much bureaucracy canhamper rescue efforts• There is a need for a global review <strong>of</strong> existing regulations• Rescue efforts do take place outside <strong>of</strong> existing protocols• Compliance is difficult• Compliance is unlikely in developing countriesWhat is unknown?• Existing regulations and protocols worldwide• Existing regulations and protocols worldwide• Actual number <strong>of</strong> entanglement cases• What <strong>the</strong> best practice guidelines are• Who would be best placed to undertake a review• What sort <strong>of</strong> legislation is needed in each place• Whe<strong>the</strong>r animal welfare is going to be a priority forany governments• Best practice for some species• What examples <strong>of</strong> best compliance are <strong>the</strong>re and what lessonscan be learnedWho knows it?• IWC, NOAA• NGOs and rescue groups• Government agenciesWho might know?• Fishing industry and fishermen• Coastal authorities• Holders <strong>of</strong> stranding databases• Public29

Annex 4Submitted abstracts accompanyingposter presentationsAbstracts are presented under <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>of</strong> reduce,remove, and rescue.Please note: all abstracts in Annex 4 are <strong>the</strong> intellectualproperty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> author and are presented here assubmitted. This annex does not contain content by<strong>WSPA</strong>; please contact individual authors for fur<strong>the</strong>rinformation or requests to quote.ReduceThe following abstracts are those submitted under <strong>the</strong><strong>the</strong>me <strong>of</strong> reducing <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> marine litter entering<strong>the</strong> oceans and harming animals.Regional cooperation and intergovernmentalagreements: key elements addressing marine debrisissues in <strong>the</strong> Wider Caribbean RegionAlessandra Vanzella-KhouriUnited Nations Environment Programme –Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP-CEP)14-20 Port Royal Street, Kingston, Jamaicaavk@cep.unep.orgThe Convention for <strong>the</strong> Protection and Development <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Marine Environment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wider Caribbean Region(Cartagena Convention, 1983) and its Protocols are <strong>the</strong>only legally binding environmental treaties for <strong>the</strong> WiderCaribbean Region and constitute a legal commitment by<strong>the</strong> participating governments to protect, develop andmanage <strong>the</strong>ir marine resources individually or jointly.Through <strong>the</strong> Protocol Concerning Specially ProtectedAreas and Wildlife (SPAW Protocol, 1990), coastal andmarine biodiversity issues are managed through anecosystem-based and integrated precautionary approachand supported through a comprehensive programme.Through <strong>the</strong> Protocol Concerning Land-based Pollutionand Activities (LBS Protocol, 1999), both point andnon-point sources <strong>of</strong> pollution, including marine debris,are addressed through an integrated environmentalprogramme, which also interacts with <strong>the</strong> GlobalProgramme <strong>of</strong> Action (GPA) on land-based pollution.The SPAW Protocol grants total protection to hundreds<strong>of</strong> species, including all species <strong>of</strong> sea turtles and marinemammals that inhabit <strong>the</strong> Wider Caribbeanand which are being affected by marine debris.A marine mammal Action Plan developed under SPAWhighlights entanglements and fisheries interactions asmajor threats to marine mammals. In this context, <strong>the</strong>UNEP administered Cartagena Convention and SPAWand LBS Protocols promote and facilitate regionalcooperation to address <strong>the</strong>se issues within a holisticframework developed and executed in partnership withgovernments, o<strong>the</strong>r UN agencies and initiatives, NGOs,<strong>the</strong> scientific community, <strong>the</strong> private sector and donorsand which supports assessments, capacity building,and management interventions.Private sector efforts to create effective,collaborative partnerships to reduce litterAshley Carlson, ConsultantAmerican Chemistry Council115 Chase Rd, Londonderry, NH 03053, USAAshley@ashleycarlsonconsulting.comOver <strong>the</strong> years numerous programs and approacheshave been developed by government agencies,industry groups and NGOs to increase public awarenessregarding marine debris, and to establish litter abatementand o<strong>the</strong>r programs to change behaviors that ultimatelylead to marine debris impacting coastal areas and<strong>the</strong> ocean.As producers <strong>of</strong> materials that have found <strong>the</strong>ir wayinto <strong>the</strong> marine environment, plastic makers are activelyinvolved in marine debris and litter prevention programsand are working with governments, scientists, retailers,anti-litter groups and consumers to devise solutions tohelp prevent marine debris.This presentation will highlight examples <strong>of</strong> severalsuccessful programs through <strong>the</strong> Declaration <strong>of</strong>Global Plastics Associations for Solutions on MarineLitter. With over 50 plastics organizations from30 countries signed on to <strong>the</strong> Declaration, thispresentation will explore global projects and partnershipsthat work to help reduce plastic from entering ourenvironment, such as <strong>the</strong> American Chemistry Council’spartnership to place nearly 700 recycling bins andeducational signage in 19 communities along <strong>the</strong>California coast; and a global industry stewardship30

Annex 4Submitted abstracts accompanyingposter presentationsImpacts <strong>of</strong> marine debris on manatees, sea turtles anddolphins in FloridaAdimey, N.M., Hudak, C., Powell, J., Bassos-Hull, K.and Minch, K.3915 Baymeadows Way, Jacksonville,Florida 32256, USANicole_Adimey@fws.govMarine debris is a global problem that has been anongoing concern for animal conservation. Entanglementin and ingestion <strong>of</strong> marine debris has been documentedin numerous marine mammal and sea turtle species(Laist, 1996). Marine debris in general can: restrictfeeding, cause starvation, restrict movement, drown orexhaust <strong>the</strong> animal, cause amputation, wounds and/or infection, decrease predator avoidance or introducetoxic chemicals into tissues (Laist, 1997). Although <strong>the</strong>reis a growing concern to mitigate <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> marinedebris on marine mammals and sea turtle populations(Johnson et al 2005), <strong>the</strong> true extent to which <strong>the</strong>secause morbidity, mortality, or population effects israrely known (Williams et al 2011). This study compiledand analyzed entanglement and ingestion data <strong>of</strong> bothactive and derelict fishing gear from dolphins, manateesand six species <strong>of</strong> sea turtles, using stranding recordsfrom Florida (1997-2009). Fishery-related gear wascategorized as follows: hook and line (HL) (fishing line,hooks, lures, etc.); trap pot gear (TPG) (any part <strong>of</strong> a trappot including buoy and line) and o<strong>the</strong>r known fishing gear(OG) not separated into <strong>the</strong> previous two categories (e.g.,net, rope). A combined total <strong>of</strong> 27323 cases among <strong>the</strong>three major groups were reported, <strong>of</strong> which 2412 wereT. truncatus, 4962 T. manatus, and 19949 Chelonioideaspp. From <strong>the</strong>se, a total <strong>of</strong> 1958 gear-on entanglementcases were analyzed; 132 T. truncatus, 433 T. manatus,and 1393 Chelonioidea spp. For all species, <strong>the</strong> majority<strong>of</strong> entanglements were ei<strong>the</strong>r ingested (I) (28.0%, n=548),occurred on <strong>the</strong> flipper (F) region (27.1% n=530) oroccurred in multiple body locations (ML) (16.3%, n=320).Overall, comparing gear versus location, 78.6% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Atlantic cases were HL (n=915) and 7.1% TPG (n=83),while in <strong>the</strong> Gulf region, 56.4% were HL (n=448) and27.1%TPG (n=215). Locations with <strong>the</strong> highest number<strong>of</strong> entanglement cases were grouped by watershedboundaries and termed “hotspots”. The overall hotspots<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> multi-species entanglements occurred in <strong>the</strong> IndianRiver / Mosquito Lagoon Complex (n=675), <strong>the</strong> FloridaKeys (n=218), and <strong>the</strong> Charlotte Harbor / Pine IslandSound Complex (n=146). The stranding data representedis a minimum estimate, as entanglement cases cango unreported or animals may be inaccessible.Management recommendations include: (1) increasededucation on impacts <strong>of</strong> fishing gear and appropriatedisposal practices, targeted especially on recreationalfishers that may not know impacts, rules and regulations;(2) coordination with industry to develop feasible gearmodification solutions such as stiffened line on crabtraps that will not allow coiling around animals (or parts);(3) <strong>the</strong> creation <strong>of</strong> a statewide entanglement coordinatorto actively work with conservation organizations toreduce entanglement hazards, assist agencies withreporting and response, and increase awareness;(4) active and regular surveillance and debris removalefforts in hotspots areas; and (5) a statewide outreachcampaign focused on <strong>the</strong> impacts and hazards <strong>of</strong>fishery-related debris on Florida wildlife, <strong>the</strong> environmentand <strong>the</strong> public.Entanglement along <strong>the</strong> Brazilian coastline:thousands <strong>of</strong> kilometers <strong>of</strong> impacts and threatsJuliana A. Ivar do Sul, Monica F. Costa andLuis Henrique B. AlvesDepartamento de Oceanografia,Universidade Federal de PernambucoAv. Arquitetura s/n Cidade Universitária,Recife, PE, Brazil. CEP 50.740-550julianasul@gmail.comStudies related to <strong>the</strong> occurrence <strong>of</strong> marine debrison beaches and coastal waters are been developedin Brazil, <strong>the</strong> largest country <strong>of</strong> South America (4°latN - 34°lat S) with more than 7,000km <strong>of</strong> a continuouscoastline, since <strong>the</strong> 1970’s. Since <strong>the</strong>n, scientists andconservationists observed and reported interactionsbetween plastics and marine animals. The most obviousis <strong>the</strong> entanglement <strong>of</strong> marine mammals, sea turtles,seabirds and fishes in nylon nets, ropes and o<strong>the</strong>rfishing-related debris. In <strong>the</strong> south region, from <strong>the</strong>frontier with Uruguay to <strong>the</strong> Peixes Lagoon, carcasses <strong>of</strong>seabirds (including albatrosses, petrels, gulls and terns,and <strong>the</strong> penguin Spheniscus magellanicus) as well asgreen sea turtles Chelonia mydas are <strong>of</strong>ten observedentangled mainly in plastic bags, ropes and nets32

Annex 4Submitted abstracts accompanyingposter presentationsdiscarded, abandoned or missed by fishery and ordinaryactivities. Individuals are also reported with plastics in<strong>the</strong>ir gastrointestinal content. In <strong>the</strong> continental platform<strong>of</strong> Rio Grande do Sul state and behind, blue sharksPrionace glauca are particularly affected by plasticrings discarded by <strong>the</strong> commercial fishing fleet. Aroundgills and/or mouth, rings hamper normal feeding andventilation, leaving animals to death. Fishing ropes andnets with several meters in length are reported at <strong>the</strong>Arvoredo Marine Biological Reserve (27°S). The Reserve,and <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn coast <strong>of</strong> Santa Catarina state, areimportant breeding areas to right whales Eubalaenaglacialis that are been reported entangled on mega(sized) debris mainly from fishing activities (includingartisanal fishery). In <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>ast region <strong>of</strong> Brazil (SãoPaulo state), rings identified as detachable lid partsfrom plastic bottles entangle carcharhinid shark species(Rhizoprionodon lalandii) and are probably related to <strong>the</strong>irdeath. In <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast region, marine invertebrates arebeing reported entangled at Todos os Santos Bay (13° S),Bahia state. Hard corals (Millepora spp.) are covered (andbroken) by nylon nets, fishing lines and o<strong>the</strong>r fishingrelateddebris. Benthic invertebrates (mollusks andcrustaceans) are also observed entangled in ordinaryobjects such as aluminum cans, glass bottles andplastic containers discarded mainly by beach users.One hundred kilometers to <strong>the</strong> north, sea turtlesEretmochelys imbricata have <strong>the</strong>ir nesting beachescontaminated by marine debris from land- and marinebasedsources. Females may become entangled on<strong>the</strong> beach during spawning. In Pernambuco state, <strong>the</strong>estuarine biota is also threatened by plastic pollution.In a small estuary (Goiana Estuary, 7°S) included in aMarine Extractive Reserve, catfishes and sea turtles areobserved entangled in nylon net fragments. Plastic bagsare observed on mangrove forests sealing <strong>of</strong> holes andobstructing crab’s passage. Since large areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Nor<strong>the</strong>ast (and North) coasts in Brazil are covered bymangrove forests, this pattern is probably spread over<strong>the</strong>se coasts. In Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (3°S,32°W), spinner dolphins Stenella longirostris interactwith plastic supermarket bags. Animals may not becomeentangled but registers are important evidences thatplastics are available to <strong>the</strong> marine biota in this protectedinsular environment. Finally, in <strong>the</strong> north region <strong>of</strong> Brazil,marine debris are already reported on beaches andriverine environments. The accidental fishery capturemarine manatees (Trichechus inunguis) and estuarinedolphins; since fishing-related debris are available <strong>the</strong>ymay entangle marine mammals on coasts and rivers,including <strong>the</strong> Amazon River. Plastic pollution along <strong>the</strong>Brazilian coastline is threating hard corals, crustaceans,mollusks, fishes, sea turtles, seabirds and marinemammals. Nowadays, few initiatives exist to reduceentanglement rates. These are almost restricted toindependent non-governmental organizations. Fishingrelateddebris are frequently pointed by researches as<strong>the</strong> main responsible for entanglements; consequently,initiatives to reduce amounts <strong>of</strong> fishing nets and nylonlines are urgently necessary and must include longlastingcampaigns and educational programs. To <strong>the</strong>accidental capture <strong>of</strong> sea turtles, seabirds and dolphinsalthough, more structured initiatives exist.Marine mammal entanglements along <strong>the</strong>United States West Coast: a reference guidefor gear identificationLauren Saez, D. Lawson, M. DeAngelis, E. Petras, S.Wilkin, and C. FahyContractor with Ocean Associates Inc. for NationalMarine Fisheries ServiceSouthwest Regional Office, Long Beach, CA 90802, USALauren.Saez@noaa.govMarine mammal, specifically large whale entanglementin commercial fishing gear <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> U.S. West Coast hasbeen identified as an issue <strong>of</strong> concern by <strong>the</strong> NationalMarine Fisheries Service (NMFS) because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> potentialimpacts to both marine mammals (individually and ata stock/population level) and <strong>the</strong> commercial fishingindustry. An average <strong>of</strong> 10 large whale entanglementswere reported per year (2000 to 2012) along <strong>the</strong> U.S.west coast, with humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae)and gray (Eschrichtius robustus) whales being <strong>the</strong>most frequently identified species. For many confirmedreports, an on-water response is not possible anda photograph or description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entanglement isall that can be obtained. For this reason, <strong>the</strong> origin<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entangling gear (active or marine debris) israrely identified for <strong>the</strong>se large whales. Therefore,NMFS created a Fixed Gear Guide to characterize <strong>the</strong>commercial fixed gear fisheries <strong>of</strong>f California, Oregon,and Washington to assist responders and managerswith identification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> entangling gear. Each fishery isthoroughly described using photos, diagrams, maps, and33