44 Europe <strong>The</strong> <strong>Economist</strong> <strong>April</strong> <strong>19</strong>th <strong>2014</strong>CharlemagneRussia’s friends in blackWhy Europe’s populists and radicals admire VladimirPutinIF EUROPE’S far-right parties do as well as many expect in May’sEuropean election, no world leader will be happier than VladimirPutin. For a man who claims to be defending Russian-speakersin Ukraine against fascists and Nazis, the Russian presidenthas some curious bedfellows on the fringes of European politics,ranging from the creepy uniformed followers ofJobbikin Hungaryto the more scrubbed-up National Front in France.<strong>The</strong>re was a time when Russia’s friends were principally onthe left. <strong>The</strong>re are still some pro-Moscow communists, for instancein Greece. Butthese daysthe Kremlin’schumsare mostvisibleon the populist right. <strong>The</strong> crisis in Ukraine has brought outtheir pro-Russian sympathies, most overtly when a motley groupof radicals was invited to vouch for Crimea’s referendum on rejoiningRussia. <strong>The</strong> “observers” included members ofthe NationalFront, Jobbik, the Vlaams Belangin Belgium, Austria’s FreedomParty (FPÖ) and Italy’s Northern League, as well as leftists fromGreece and Germany and an assortment of eccentrics. <strong>The</strong>y declaredthat the ballot, denounced by most Western governmentsas illegitimate, had been exemplary.So what does Europe’s farright see in MrPutin? As nationalistsof various stripes, their sympathies might have lain with theirUkrainian fellows fighting to escape Russian influence. In fact, arguesPeter Kreko of Political Capital, a Hungarian think-tank, beyondfavourable treatment in Russian-sponsored media, manyare attracted by Mr Putin’s muscular assertion of national interests,his emphasis on Christian tradition, his opposition to homosexualityand the way he has brought vital economic sectors understate control. For some, pan-Slavic ideas in eastern Europeplay a role. A common thread is that many on the far right shareMr Putin’s hatred for an order dominated by America and theEuropean Union. For Mr Putin, support from the far right offers asecond channel for influence in Europe.<strong>The</strong> flirtation with Russia first became apparent in eastern Europesome yearsago, despite memoriesofSovietoccupation. Jobbik,which took 20% of the vote in Hungary’s recent election, denouncedRussian riots in Estonia afterthe removal ofa Sovietwarmemorial in 2007. Buta yearlateritbacked Russia’smilitaryinterventionin Georgia. Far-right parties in Bulgaria and Slovakia alsosupported Russia. Since then, Russian influence has become apparentin western Europe, too. Marine Le Pen, leader of the NationalFront, has been given red-carpet treatment in Moscow andeven visited Crimea last year. At December’s congress of Italy’sNorthern League, pro-Putin officials were applauded when theyspoke of sharing “common Christian European values”. Amongthose attending were three nascent allies: Geert Wilders of theNetherlands’ Party for Freedom, Heinz-Christian Strache of theFPÖ, and Ludovic de Danne, Ms Le Pen’s European adviser.ForMrde Danne the parties share an aversion to the euro and,more widely, to the EU’s federalist dream. <strong>The</strong>y oppose globalisationand favour protectionism. <strong>The</strong>y seek a “Europe of homelands”,stretching from Lisbon to Vladivostok. As for Ukraine, hecalls the revolution in Kiev “illegitimate” and says the referendumin Crimea was justified by the pro-Russian sentiment of theCrimean population. By attaching themselves to the EU andAmerica, Ukraine’s new rulers expose their country to IMF oppressionand the pillage of its natural resources. Such dalliancewith MrPutin may create trouble forMrWilders, who sees the EUas a monster but is a strong supporter of gay rights. According toMr de Danne, the Eurosceptic alliance has agreed to co-ordinateonly on internal EU matters, not international affairs.A degree of admiration for Mr Putin also stretches to Britain’sUK Independence Party (UKIP). It sees Ms Le Pen and Mr Wildersas too tainted by racism and is parting ways with the NorthernLeague. But UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, while insisting he dislikesMr Putin’s methods, thinks the Russian leader has skilfullywrong-footed America and Europe. <strong>The</strong> EU, he declared in a televiseddebate, “hasblood on itshands” forraisingUkraine’shopesof EU membership and provoking Mr Putin. Mr Farage’s critiqueis perhaps a way of attacking the EU’s enlargement policy, whichis now linked by many to immigration. Yet it is also an implicit admissionthat the club remains attractive to those outside it.Hello, ComradeMr Putin is too clever to rely only on Europe’s insurgent parties,successful as some may be. So as well as cultivating anti-establishmentgroups, he has worked to entice national elites. WhileJobbikadvocates closer economic relations with the east, Hungary’sprime minister, Viktor Orban, is already doing it. A veteran ofthe struggle against communism, embodying the catchphrase“Goodbye, Comrade”, Mr Orban recently signed a deal with Russiato expand a nuclear-power plant, financed by a €10 billion($14 billion) Russian loan. He has sought to weaken Europeansanctions against Russia. In Italy the Northern League’s leader,Matteo Salvini, may shout “viva the referendum in Crimea”, butMatteo Renzi, the centre-left prime minister, has also been assiduousin resisting tough sanctions.Anti-EU parties will no doubt become stronger and noisier,but they lack the numbers and the cohesion fundamentally tochange EU business in the European Parliament. <strong>The</strong>ir effect willbe more subtle. <strong>The</strong>y may force mainstream parties in the parliamentinto more backroom deals, deepening the EU’s democraticdeficit. <strong>The</strong>ir agitation is more likely to influence national politicsand to push governments into more Eurosceptic positions. Andthey will provide an echo chamber for Mr Putin, making it harderstill for the Europeans to come up with a firm and united responseto Mr Putin’s military challenge to the post-war order inEurope. <strong>The</strong>re is more at stake in May than a protest vote. 7<strong>Economist</strong>.com/blogs/charlemagne

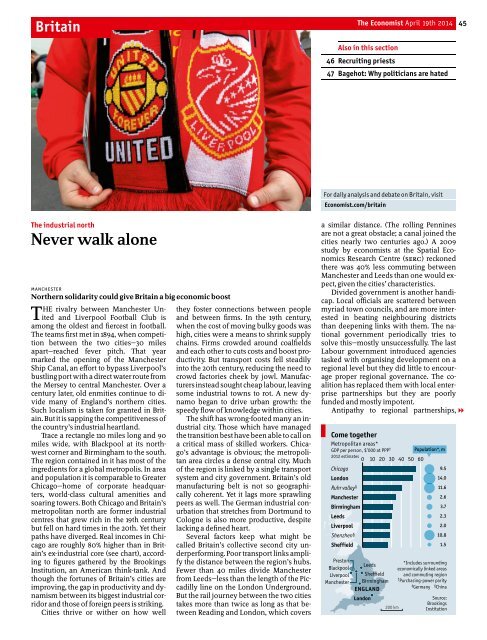

Britain<strong>The</strong> <strong>Economist</strong> <strong>April</strong> <strong>19</strong>th <strong>2014</strong> 45Also in this section46 Recruiting priests47 Bagehot: Why politicians are hatedFor daily analysis and debate on Britain, visit<strong>Economist</strong>.com/britain<strong>The</strong> industrial northNever walk aloneMANCHESTERNorthern solidarity could give Britain a big economic boostTHE rivalry between Manchester Unitedand Liverpool Football Club isamong the oldest and fiercest in football.<strong>The</strong> teams first met in 1894, when competitionbetween the two cities—30 milesapart—reached fever pitch. That yearmarked the opening of the ManchesterShip Canal, an effort to bypass Liverpool’sbustlingportwith a directwaterroute fromthe Mersey to central Manchester. Over acentury later, old enmities continue to dividemany of England’s northern cities.Such localism is taken for granted in Britain.But it is sappingthe competitiveness ofthe country’s industrial heartland.Trace a rectangle 110 miles long and 90miles wide, with Blackpool at its northwestcorner and Birmingham to the south.<strong>The</strong> region contained in it has most of theingredients for a global metropolis. In areaand population it is comparable to GreaterChicago—home of corporate headquarters,world-class cultural amenities andsoaring towers. Both Chicago and Britain’smetropolitan north are former industrialcentres that grew rich in the <strong>19</strong>th centurybut fell on hard times in the 20th. Yet theirpaths have diverged. Real incomes in Chicagoare roughly 80% higher than in Britain’sex-industrial core (see chart), accordingto figures gathered by the BrookingsInstitution, an American think-tank. Andthough the fortunes of Britain’s cities areimproving, the gap in productivity and dynamismbetween its biggest industrial corridorand those offoreign peers is striking.Cities thrive or wither on how wellthey foster connections between peopleand between firms. In the <strong>19</strong>th century,when the cost of moving bulky goods washigh, cities were a means to shrink supplychains. Firms crowded around coalfieldsand each other to cuts costs and boost productivity.But transport costs fell steadilyinto the 20th century, reducing the need tocrowd factories cheek by jowl. Manufacturersinstead sought cheap labour, leavingsome industrial towns to rot. A new dynamobegan to drive urban growth: thespeedy flow ofknowledge within cities.<strong>The</strong> shift has wrong-footed many an industrialcity. Those which have managedthe transition best have been able to call ona critical mass of skilled workers. Chicago’sadvantage is obvious; the metropolitanarea circles a dense central city. Muchof the region is linked by a single transportsystem and city government. Britain’s oldmanufacturing belt is not so geographicallycoherent. Yet it lags more sprawlingpeers as well. <strong>The</strong> German industrial conurbationthat stretches from Dortmund toCologne is also more productive, despitelacking a defined heart.Several factors keep what might becalled Britain’s collective second city underperforming.Poor transport links amplifythe distance between the region’s hubs.Fewer than 40 miles divide Manchesterfrom Leeds—less than the length of the Piccadillyline on the London Underground.But the rail journey between the two citiestakes more than twice as long as that betweenReading and London, which coversa similar distance. (<strong>The</strong> rolling Penninesare not a great obstacle; a canal joined thecities nearly two centuries ago.) A 2009study by economists at the Spatial EconomicsResearch Centre (SERC) reckonedthere was 40% less commuting betweenManchester and Leeds than one would expect,given the cities’ characteristics.Divided government is another handicap.Local officials are scattered betweenmyriad town councils, and are more interestedin beating neighbouring districtsthan deepening links with them. <strong>The</strong> nationalgovernment periodically tries tosolve this—mostly unsuccessfully. <strong>The</strong> lastLabour government introduced agenciestasked with organising development on aregional level but they did little to encourageproper regional governance. <strong>The</strong> coalitionhas replaced them with local enterprisepartnerships but they are poorlyfunded and mostly impotent.Antipathy to regional partnerships, 1Come togetherMetropolitan areas*GDP per person, $’000 at PPP †Population*, m2012 estimates0 10 20 30 40 50 60Chicago9.5London14.0Ruhr valley ‡11.6Manchester2.6Birmingham3.7Leeds2.3Liverpool2.0Shenzhen §10.8Sheffield1.5PrestonLeedsBlackpoolLiverpool SheffieldManchester BirminghamENGLANDLondon200 km*Includes surroundingeconomically linked areasand commuting region† Purchasing-power parity‡ Germany § ChinaSource:BrookingsInstitution