- Page 2 and 3:

?UnderstandingSyntaxThird edition

- Page 4 and 5:

ContentsiiiUnderstandingSyntaxThird

- Page 6 and 7:

?For S.J. and Maggie the younger,th

- Page 8 and 9:

?ContentsAcknowledgementsNote to th

- Page 10 and 11:

Contentsix4.2 Where does the head o

- Page 12 and 13:

?AcknowledgementsOver the 13 years

- Page 14 and 15:

?Note to the studentThis book is an

- Page 16 and 17:

?List of abbreviations used in exam

- Page 18 and 19:

1What is syntax?1.1 Some concepts a

- Page 20 and 21:

What is syntax? 3way doesn’t func

- Page 22 and 23:

What is syntax? 5wonder why (7) is

- Page 24 and 25:

What is syntax? 7So if the word Has

- Page 26 and 27:

What is syntax? 9b. Why hydestow (i

- Page 28 and 29:

What is syntax? 11use of they in (2

- Page 30 and 31:

1.2.2 How to read linguistic exampl

- Page 32 and 33:

What is syntax? 15glosses contain o

- Page 34 and 35:

What is syntax? 17some third party,

- Page 36 and 37:

What is syntax? 19some of the examp

- Page 38 and 39:

What is syntax? 21need to be able t

- Page 40 and 41:

What is syntax? 23verb (counted out

- Page 42 and 43:

(49) a. I charged the battery up.b.

- Page 44 and 45:

What is syntax? 27Standard dialectm

- Page 46 and 47:

What is syntax? 29Republic of Vanua

- Page 48 and 49:

What is syntax? 31∑ Tinrin has a

- Page 50 and 51:

Words belong to different classes 3

- Page 52 and 53:

Words belong to different classes 3

- Page 54 and 55:

Words belong to different classes 3

- Page 56 and 57:

Words belong to different classes 3

- Page 58 and 59:

Words belong to different classes 4

- Page 60 and 61:

Words belong to different classes 4

- Page 62 and 63:

Words belong to different classes 4

- Page 64 and 65:

Words belong to different classes 4

- Page 66 and 67:

Words belong to different classes 4

- Page 68 and 69:

Words belong to different classes 5

- Page 70 and 71:

Words belong to different classes 5

- Page 72 and 73:

Words belong to different classes 5

- Page 74 and 75:

Words belong to different classes 5

- Page 76 and 77:

Words belong to different classes 5

- Page 78 and 79:

Words belong to different classes 6

- Page 80 and 81:

Words belong to different classes 6

- Page 82 and 83:

(82) I’ll see you right/straight/

- Page 84 and 85:

Words belong to different classes 6

- Page 86 and 87:

(11) I’m not that bothered about

- Page 88 and 89:

Words belong to different classes 7

- Page 90 and 91:

3Looking inside sentencesThis chapt

- Page 92 and 93:

Looking inside sentences 75grammati

- Page 94 and 95:

Looking inside sentences 77∑ Moda

- Page 96 and 97:

Looking inside sentences 79the same

- Page 98 and 99:

Looking inside sentences 81Look at

- Page 100 and 101:

Looking inside sentences 83in this

- Page 102 and 103:

Looking inside sentences 85claimed,

- Page 104 and 105:

Looking inside sentences 87clause

- Page 106 and 107:

Looking inside sentences 89Here are

- Page 108 and 109:

Looking inside sentences 91This is

- Page 110 and 111:

Looking inside sentences 93In (50),

- Page 112 and 113:

Looking inside sentences 95heard yo

- Page 114 and 115:

Looking inside sentences 97get *Mus

- Page 116 and 117:

Looking inside sentences 99for the

- Page 118 and 119:

Looking inside sentences 101(2) Dar

- Page 120 and 121:

(9) Deir sé [nach dtuigeann sé an

- Page 122 and 123:

Looking inside sentences 105(9) a.

- Page 124 and 125:

Looking inside sentences 107(5) ri

- Page 126 and 127:

Heads and their dependents 109quite

- Page 128 and 129:

Heads and their dependents 111Third

- Page 130 and 131:

Heads and their dependents 113in th

- Page 132 and 133:

Heads and their dependents 115∑Gi

- Page 134 and 135:

Heads and their dependents 117(15)

- Page 136 and 137:

Heads and their dependents 119Altho

- Page 138 and 139:

Heads and their dependents 121Tinri

- Page 140 and 141:

Heads and their dependents 123∑Nd

- Page 142 and 143:

Heads and their dependents 125(33)

- Page 144 and 145:

Heads and their dependents 127(39)

- Page 146 and 147:

4.3.4.2 Head-marking in the possess

- Page 148 and 149:

Heads and their dependents 131(48)

- Page 150 and 151:

Heads and their dependents 133is tr

- Page 152 and 153:

Heads and their dependents 135Exerc

- Page 154 and 155:

Heads and their dependents 1374. Th

- Page 156 and 157:

Heads and their dependents 139found

- Page 158 and 159:

5How do we identify constituents?Th

- Page 160 and 161:

How do we identify constituents? 14

- Page 162 and 163:

How do we identify constituents? 14

- Page 164 and 165:

(20) [Kim wrote [that book with the

- Page 166 and 167: How do we identify constituents? 14

- Page 168 and 169: How do we identify constituents? 15

- Page 170 and 171: How do we identify constituents? 15

- Page 172 and 173: How do we identify constituents? 15

- Page 174 and 175: How do we identify constituents? 15

- Page 176 and 177: 5.3.1.2 Tree structures for phrasal

- Page 178 and 179: How do we identify constituents? 16

- Page 180 and 181: How do we identify constituents? 16

- Page 182 and 183: How do we identify constituents? 16

- Page 184 and 185: How do we identify constituents? 16

- Page 186 and 187: How do we identify constituents? 16

- Page 188 and 189: How do we identify constituents? 17

- Page 190 and 191: Relationships within the clause 173

- Page 192 and 193: Relationships within the clause 175

- Page 194 and 195: Relationships within the clause 177

- Page 196 and 197: Relationships within the clause 179

- Page 198 and 199: Relationships within the clause 181

- Page 200 and 201: Relationships within the clause 183

- Page 202 and 203: Relationships within the clause 185

- Page 204 and 205: Relationships within the clause 187

- Page 206 and 207: Relationships within the clause 189

- Page 208 and 209: Relationships within the clause 191

- Page 210 and 211: Relationships within the clause 193

- Page 212 and 213: (54) Ruš‐a gadadi-z cük ga-na.g

- Page 214 and 215: Relationships within the clause 197

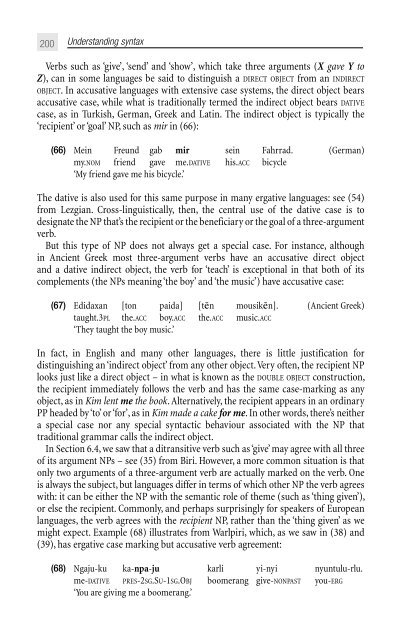

- Page 218 and 219: Relationships within the clause 201

- Page 220 and 221: Relationships within the clause 203

- Page 222 and 223: Relationships within the clause 205

- Page 224 and 225: (5) wičháša ki mathó óta w

- Page 226 and 227: Relationships within the clause 209

- Page 228 and 229: 7Processes that change grammatical

- Page 230 and 231: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 232 and 233: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 234 and 235: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 236 and 237: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 238 and 239: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 240 and 241: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 242 and 243: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 244 and 245: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 246 and 247: 7.4 The causative constructionProce

- Page 248 and 249: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 250 and 251: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 252 and 253: (2) Da rara hàmu da pàu.they be.r

- Page 254 and 255: (3) bey‐mu‐ban2sg(Su)/1sg(Obj)

- Page 256 and 257: A. Bare(1) a. [kwati i i-karuka tš

- Page 258 and 259: Processes that change grammatical r

- Page 260 and 261: 8Wh-constructions: Questions and re

- Page 262 and 263: Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 264 and 265: Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 266 and 267:

8.1.3 Multiple wh-questionsWh-const

- Page 268 and 269:

. Inona no novidin’ iza?what prt

- Page 270 and 271:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 272 and 273:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 274 and 275:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 276 and 277:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 278 and 279:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 280 and 281:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 282 and 283:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 284 and 285:

(2) a. Ddaru Mair weld y ffilm?aux.

- Page 286 and 287:

Wh-constructions: Questions and rel

- Page 288 and 289:

9Asking questions about syntaxThe t

- Page 290 and 291:

Asking questions about syntax 273su

- Page 292 and 293:

Asking questions about syntax 275(1

- Page 294 and 295:

(23) a. Cerddon nhw i ’r dre.walk

- Page 296 and 297:

Asking questions about syntax 279fu

- Page 298 and 299:

Asking questions about syntax 281Th

- Page 300 and 301:

Asking questions about syntax 283Is

- Page 302 and 303:

Asking questions about syntax 285un

- Page 304 and 305:

Sources of data used in examplesDat

- Page 306 and 307:

Sources of data used in examples 28

- Page 308 and 309:

GlossaryThis glossary contains brie

- Page 310 and 311:

Glossary 293This phenomenon is know

- Page 312 and 313:

Glossary 295proform: A word which s

- Page 314 and 315:

References 297Beale, Anthony (1974)

- Page 316 and 317:

References 299Dixon, R. M. W. and A

- Page 318 and 319:

References 301Levinson, Stephen C.

- Page 320 and 321:

References 303Sohn, Ho-Min (1999).

- Page 322 and 323:

Language index 305French (Romance:

- Page 324 and 325:

1Subject indexabsolutive case (see

- Page 326 and 327:

Subject index 309critical period 28

- Page 328 and 329:

Subject index 311double 200indirect