3. Education and fairnessRebecca HickmanCui bono – who benefits?It is familiar territory to consider the principle offairness in relation to public service delivery andoutcomes. The concept of fairness is sufficientlyvague to make it an appealing touchstonefor politicians of all hues. It is convenientlysusceptible to being invoked to lend credibilityto an ideologically driven political agenda andless often used to direct and shape the content ofthat agenda. As Roy Hattersley once commented,‘We all believe in fairness and define it accordingto taste.’So we need to define terms; craft a meaningfuldefinition of fairness, capable of a degree ofobjective application. To this end, in the sphereof education policy, the cui bono principleprovides us with a useful tool. Who stands tobenefit? Who do the structures, operation andrepercussions of a particular education systemreward, and who finds their starting position ofrelative disadvantage unchanged or worsened?Fairness would demand that everyone benefits,that outcomes improve across the board, whileinequality and socially determined attainmentreduce. In that case, our vision of fairness mightbe summed up as educational systems andprovision that redistribute opportunities, powerand resources across lifetimes and generations.Conversely, unfairness would be educationalsystems and provision that reproduce andentrench existing patterns of (dis)advantageand social inequality, thereby creating a kindof social closure. Crucially, this definition offairness clearly speaks of ends as well as means,destinations as well as journeys.The application of such a definition requiresattention to a number of questions. First, whereis the locus of responsibility: to what extent doesit rest with the state, and should the achievementof fairness ever depend on, say, the degree ofactive participation by parents? Second, mustfairness be universal: morally and practically,can it be achieved for one child if it has beendenied another? Third, what is the relationshipof fairness to democratic accountability at localand national levels? Fourth, in what respectsis fairness unavoidably eroded by a faithfulattachment to market mores, and what level ofempirical evidence must we demand of market orany other solutions?Markets and schoolingResearch suggests that the expansion in educationprovision of the past 60 years has helped the‘haves’ to entrench their privileged position atthe expense of the ‘have nots’ and that the relationshipbetween family income and educationalattainment in the UK has actually strengthenedover time. In other words, having notionally‘equal’ access to educational opportunity is notthe same thing as having equal prospects of benefitingfrom educational provision. To achieve thelatter, proactive interventions are required onbehalf of those who bring fewer resources andlesser know-how to the table.In education, the Conservatives havetraditionally focused more on the enablingstructures for equivalent learning inputs than onthe actual and measurable outputs of the system.In other words, they stand accused by Labour(and, once, the Liberal Democrats) of neglectingthe wider circumstances and factors that mediateeducational destinies – factors such as individualcapabilities, household income, family practicesand social capital. The Conservatives mightnonetheless argue that the system they create isfair – providing theoretical equal opportunities toprogress to children from all backgrounds.But the current Coalition Government’sunseemly dash towards all-out marketisationbetrays an idolatry of means that is not consistentwith a commitment to just outcomes. Cui bono?Who stands to benefit from academies, freeschools, diminished local education authoritiesand the proliferation of admissions authorities?Certainly central government. For all the rhetoricof localism, the secretary of state is taking back tohimself considerable direct powers over schools,exercised through funding agreements withacademies and free schools, not to mention directresponsibility for areas such as teacher trainingand curriculum and exams.Education for the good society | 19

1 In 2008, 15 per cent ofacademies and communitytechnology colleges wereestimated to use partial selectionby aptitude in subject, comparedwith less than 1 per cent ofcommunity and voluntarycontrolledsecondary schools.See Anne West, Eleanor Barhamand Audrey Hind, SecondarySchool Admissions in England:Policy and Practice, EducationResearch Group, London Schoolof Economics, 2009, p.18, www.risetrust.org.uk/Secondary.pdf.2 Jens Henrik Haahr, ExplainingStudent Performance: Evidencefrom the International PISA,TIMSS and PIRLS Surveys, DanishTechnological Institute, 2005,p.150, www.ec.europa.eu/education/pdf/doc282_en.pdf.Governing bodies may have an enhancedrole, but their statutory responsibilities extendprimarily to Whitehall, not to parents or thewider community. There is no requirement forschools to consult parents before converting toacademy status and while maintained schools arerequired to have at least three parent governors,academies must have only one. In fact, academiesonly have to have three governors in total, hardlya model of accountability to the local communitywhen, at the same time, the ability of localauthorities to plan for and support fairnessand quality across the board has been fatallyundermined. Academies also use selection byaptitude more than community and voluntarycontrolledschools, 1 so as academies spread, sowill selection; and by definition parents’ ability tochoose will be constrained.So if parents do not stand to benefit fromchoice and voice, will children benefit fromimproved quality of provision and attainmentlevels? The evidence suggests not. A 2005 metastudy by the Danish Technological Institute forthe European Commission considered threeinternational surveys of students’ skills, PISA,TIMSS and PIRLS, and found that:‘More differentiated school systems are associatedwith higher variance in student performance.…Students’ socio-economic background mattersmore for their performance in more differentiatedschool systems than in less differentiated schoolsystems. Or in other words: Less differentiated,more comprehensive school systems are moreefficient in adjusting for students’ socio-economicbackground and thus in providing equal learningopportunities for students.’ 2Markets have a multiplier effect – they do notredress the different resources and capabilitiesthat people bring to the table, they amplifythem. This is partly because markets rest onderegulation and choice, and when choice issupreme an equal ability to understand andnavigate the system is a precondition of fairoutcomes. But social capital is not and will neverbe evenly spread. So the increasingly clutteredlandscape of multiple school types and complexadmissions processes will continue to work to thebenefit of those parents with the understandingand wherewithal to engage most successfullywith the system. In other words, as a result ofthe superior social capital of the better-off, aneducational market simply becomes a mechanismfor them to bequeath their advantages to the nextgeneration.Furthermore, market logic requires thatschools are differentiated hierarchically notlaterally, in order to provide incentives. Or toput it more starkly, for educational marketsto operate effectively their own internal lawsdeem it desirable that some schools – andhence some children’s learning opportunities– are worse than others. As a result, our schoolsystem becomes unavoidably characterised bycompetition and struggle. Winners and losersare created as parents and children are forced toengage with the system as consumers pursuingrelative advantage, rather than as citizens witha crucial wider role to play as co-producers ofeducation in a collective project.Under the Conservatives’ market model,vital services provided centrally by educationauthorities for all local schools and particularlyvalued by those serving disadvantagedcatchments, such as educational welfare andethnic minority achievement, become unviable asbudgets are dispersed. At the same time, evidenceis emerging that local authority budgets are beingtop-sliced to pay for the costs of the academyscheme – resources being taken away from themajority to benefit the minority. We might callsuch a system educational Darwinism. If it is fair,it is the type of fairness propounded by those whobelieve that it is right and inevitable that only thestrong and able will succeed.The USA and Sweden have experimented withschool models akin to the academies and freeschools now being championed by the CoalitionGovernment. Not only is there evidence of fallingstandards in both countries, recent studies havealso pointed to greater racial and socio-economicsegregation between schools, as well as greaterdifferentiation in attainment between childrenfrom different backgrounds.In 2010, Swedish education minister BertilOstberg warned the UK against adopting hiscountry’s free schools model:‘We have actually seen a fall in the quality ofSwedish schools since the free schools wereintroduced. The free schools are generally20 | www.compassonline.org.uk

- Page 1 and 2: Educationfor theGoodSocietyThe valu

- Page 3 and 4: Acknowledgements:Compass would like

- Page 5 and 6: ContributorsLisa Nandy is Labour MP

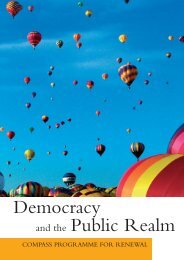

- Page 7 and 8: IntroductionEducation for the Good

- Page 9 and 10: 1 This article has been developedou

- Page 11 and 12: 8 See Ann Hodgson, Ken Spoursand Ma

- Page 13 and 14: 13 The most comprehensiverecent res

- Page 15 and 16: 1 See for example B. Simon, ‘Cane

- Page 17 and 18: 10 J. Martin, Making Socialists: Ma

- Page 19: the poorest homes (as measured by e

- Page 23 and 24: 1 Angela McRobbie, The Aftermathof

- Page 25 and 26: 8 Christine Skelton, Schooling theB

- Page 27 and 28: 1 See www.education.gov.uk/b0065507

- Page 29 and 30: 13 Barbara Fredrickson, ‘Therole

- Page 31 and 32: 6. Education forsustainabilityTeres

- Page 33 and 34: well as cognitively. Real understan

- Page 35 and 36: 7. Schools fordemocracyMichael Fiel

- Page 37 and 38: and joyful relations between person

- Page 39 and 40: 8 Wilfred Carr and AnthonyHartnett,

- Page 41 and 42: 1 Winston Churchill, quoted inNIACE

- Page 43 and 44: 9 See http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/ed

- Page 45 and 46: 1 The Learning Age: A Renaissancefo

- Page 47 and 48: nities, and not have the public-pri

- Page 49 and 50: 4 Engineering flexibility: a system

- Page 51 and 52: other countries to require their re

- Page 53 and 54: 6. Remember that many of the outcom

- Page 55 and 56: 2 Adrian Elliott, State SchoolsSinc

- Page 57 and 58: 4 Peter Hyman, ‘Fear on the front

- Page 59 and 60: 12. Rethinking thecomprehensive ide

- Page 61 and 62: training, be part of a local system

- Page 64: About CompassCompass is the democra

![[2012] UKUT 399 (TCC)](https://img.yumpu.com/51352289/1/184x260/2012-ukut-399-tcc.jpg?quality=85)

![Neutral Citation Number: [2009] EWHC 3198 (Ch) Case No: CH ...](https://img.yumpu.com/50120201/1/184x260/neutral-citation-number-2009-ewhc-3198-ch-case-no-ch-.jpg?quality=85)