ANZCA Bulletin June 2012 - final.pdf - Australian and New Zealand ...

ANZCA Bulletin June 2012 - final.pdf - Australian and New Zealand ...

ANZCA Bulletin June 2012 - final.pdf - Australian and New Zealand ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

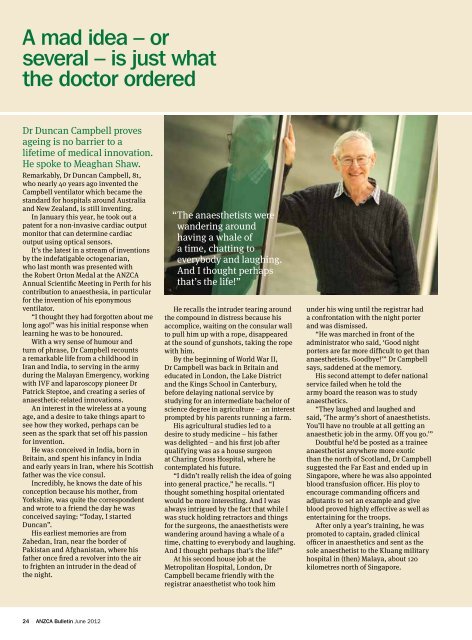

A mad idea – orseveral – is just whatthe doctor orderedDr Duncan Campbell provesageing is no barrier to alifetime of medical innovation.He spoke to Meaghan Shaw.Remarkably, Dr Duncan Campbell, 81,who nearly 40 years ago invented theCampbell ventilator which became thest<strong>and</strong>ard for hospitals around Australia<strong>and</strong> <strong>New</strong> Zeal<strong>and</strong>, is still inventing.In January this year, he took out apatent for a non-invasive cardiac outputmonitor that can determine cardiacoutput using optical sensors.It’s the latest in a stream of inventionsby the indefatigable octogenarian,who last month was presented withthe Robert Orton Medal at the <strong>ANZCA</strong>Annual Scientific Meeting in Perth for hiscontribution to anaesthesia, in particularfor the invention of his eponymousventilator.“I thought they had forgotten about melong ago!” was his initial response whenlearning he was to be honoured.With a wry sense of humour <strong>and</strong>turn of phrase, Dr Campbell recountsa remarkable life from a childhood inIran <strong>and</strong> India, to serving in the armyduring the Malayan Emergency, workingwith IVF <strong>and</strong> laparoscopy pioneer DrPatrick Steptoe, <strong>and</strong> creating a series ofanaesthetic-related innovations.An interest in the wireless at a youngage, <strong>and</strong> a desire to take things apart tosee how they worked, perhaps can beseen as the spark that set off his passionfor invention.He was conceived in India, born inBritain, <strong>and</strong> spent his infancy in India<strong>and</strong> early years in Iran, where his Scottishfather was the vice consul.Incredibly, he knows the date of hisconception because his mother, fromYorkshire, was quite the correspondent<strong>and</strong> wrote to a friend the day he wasconceived saying: “Today, I startedDuncan”.His earliest memories are fromZahedan, Iran, near the border ofPakistan <strong>and</strong> Afghanistan, where hisfather once fired a revolver into the airto frighten an intruder in the dead ofthe night.“ The anaesthetists werew<strong>and</strong>ering aroundhaving a whale ofa time, chatting toeverybody <strong>and</strong> laughing.And I thought perhapsthat’s the life!”He recalls the intruder tearing aroundthe compound in distress because hisaccomplice, waiting on the consular wallto pull him up with a rope, disappearedat the sound of gunshots, taking the ropewith him.By the beginning of World War II,Dr Campbell was back in Britain <strong>and</strong>educated in London, the Lake District<strong>and</strong> the Kings School in Canterbury,before delaying national service bystudying for an intermediate bachelor ofscience degree in agriculture – an interestprompted by his parents running a farm.His agricultural studies led to adesire to study medicine – his fatherwas delighted – <strong>and</strong> his first job afterqualifying was as a house surgeonat Charing Cross Hospital, where hecontemplated his future.“I didn’t really relish the idea of goinginto general practice,” he recalls. “Ithought something hospital orientatedwould be more interesting. And I wasalways intrigued by the fact that while Iwas stuck holding retractors <strong>and</strong> thingsfor the surgeons, the anaesthetists werew<strong>and</strong>ering around having a whale of atime, chatting to everybody <strong>and</strong> laughing.And I thought perhaps that’s the life!”At his second house job at theMetropolitan Hospital, London, DrCampbell became friendly with theregistrar anaesthetist who took himunder his wing until the registrar hada confrontation with the night porter<strong>and</strong> was dismissed.“He was marched in front of theadministrator who said, ‘Good nightporters are far more difficult to get thananaesthetists. Goodbye!’” Dr Campbellsays, saddened at the memory.His second attempt to defer nationalservice failed when he told thearmy board the reason was to studyanaesthetics.“They laughed <strong>and</strong> laughed <strong>and</strong>said, ‘The army’s short of anaesthetists.You’ll have no trouble at all getting ananaesthetic job in the army. Off you go.’”Doubtful he’d be posted as a traineeanaesthetist anywhere more exoticthan the north of Scotl<strong>and</strong>, Dr Campbellsuggested the Far East <strong>and</strong> ended up inSingapore, where he was also appointedblood transfusion officer. His ploy toencourage comm<strong>and</strong>ing officers <strong>and</strong>adjutants to set an example <strong>and</strong> giveblood proved highly effective as well asentertaining for the troops.After only a year’s training, he waspromoted to captain, graded clinicalofficer in anaesthetics <strong>and</strong> sent as thesole anaesthetist to the Kluang militaryhospital in (then) Malaya, about 120kilometres north of Singapore.24 <strong>ANZCA</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> <strong>June</strong> <strong>2012</strong>