ANZCA Bulletin June 2012 - final.pdf - Australian and New Zealand ...

ANZCA Bulletin June 2012 - final.pdf - Australian and New Zealand ...

ANZCA Bulletin June 2012 - final.pdf - Australian and New Zealand ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

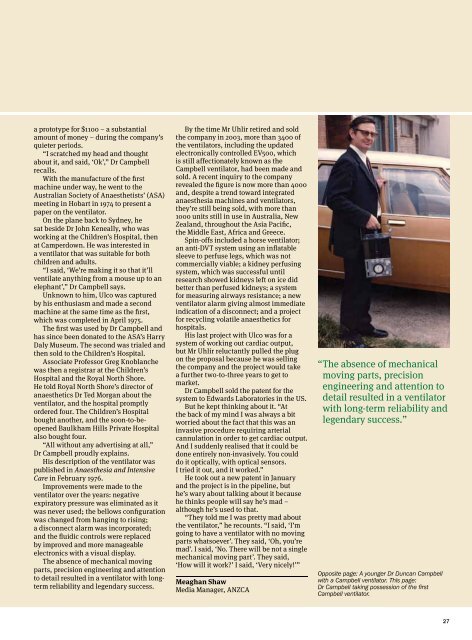

a prototype for $1100 – a substantialamount of money – during the company’squieter periods.“I scratched my head <strong>and</strong> thoughtabout it, <strong>and</strong> said, ‘Ok’,” Dr Campbellrecalls.With the manufacture of the firstmachine under way, he went to the<strong>Australian</strong> Society of Anaesthetists’ (ASA)meeting in Hobart in 1974 to present apaper on the ventilator.On the plane back to Sydney, hesat beside Dr John Keneally, who wasworking at the Children’s Hospital, thenat Camperdown. He was interested ina ventilator that was suitable for bothchildren <strong>and</strong> adults.“I said, ‘We’re making it so that it’llventilate anything from a mouse up to anelephant’,” Dr Campbell says.Unknown to him, Ulco was capturedby his enthusiasm <strong>and</strong> made a secondmachine at the same time as the first,which was completed in April 1975.The first was used by Dr Campbell <strong>and</strong>has since been donated to the ASA’s HarryDaly Museum. The second was trialed <strong>and</strong>then sold to the Children’s Hospital.Associate Professor Greg Knoblanchewas then a registrar at the Children’sHospital <strong>and</strong> the Royal North Shore.He told Royal North Shore’s director ofanaesthetics Dr Ted Morgan about theventilator, <strong>and</strong> the hospital promptlyordered four. The Children’s Hospitalbought another, <strong>and</strong> the soon-to-beopenedBaulkham Hills Private Hospitalalso bought four.“All without any advertising at all,”Dr Campbell proudly explains.His description of the ventilator waspublished in Anaesthesia <strong>and</strong> IntensiveCare in February 1976.Improvements were made to theventilator over the years: negativeexpiratory pressure was eliminated as itwas never used; the bellows configurationwas changed from hanging to rising;a disconnect alarm was incorporated;<strong>and</strong> the fluidic controls were replacedby improved <strong>and</strong> more manageableelectronics with a visual display.The absence of mechanical movingparts, precision engineering <strong>and</strong> attentionto detail resulted in a ventilator with longtermreliability <strong>and</strong> legendary success.By the time Mr Uhlir retired <strong>and</strong> soldthe company in 2003, more than 3400 ofthe ventilators, including the updatedelectronically controlled EV500, whichis still affectionately known as theCampbell ventilator, had been made <strong>and</strong>sold. A recent inquiry to the companyrevealed the figure is now more than 4000<strong>and</strong>, despite a trend toward integratedanaesthesia machines <strong>and</strong> ventilators,they’re still being sold, with more than1000 units still in use in Australia, <strong>New</strong>Zeal<strong>and</strong>, throughout the Asia Pacific,the Middle East, Africa <strong>and</strong> Greece.Spin-offs included a horse ventilator;an anti-DVT system using an inflatablesleeve to perfuse legs, which was notcommercially viable; a kidney perfusingsystem, which was successful untilresearch showed kidneys left on ice didbetter than perfused kidneys; a systemfor measuring airways resistance; a newventilator alarm giving almost immediateindication of a disconnect; <strong>and</strong> a projectfor recycling volatile anaesthetics forhospitals.His last project with Ulco was for asystem of working out cardiac output,but Mr Uhlir reluctantly pulled the plugon the proposal because he was sellingthe company <strong>and</strong> the project would takea further two-to-three years to get tomarket.Dr Campbell sold the patent for thesystem to Edwards Laboratories in the US.But he kept thinking about it. “Atthe back of my mind I was always a bitworried about the fact that this was aninvasive procedure requiring arterialcannulation in order to get cardiac output.And I suddenly realised that it could bedone entirely non-invasively. You coulddo it optically, with optical sensors.I tried it out, <strong>and</strong> it worked.”He took out a new patent in January<strong>and</strong> the project is in the pipeline, buthe’s wary about talking about it becausehe thinks people will say he’s mad –although he’s used to that.“They told me I was pretty mad aboutthe ventilator,” he recounts. “I said, ‘I’mgoing to have a ventilator with no movingparts whatsoever’. They said, ‘Oh, you’remad’. I said, ‘No. There will be not a singlemechanical moving part’. They said,‘How will it work?’ I said, ‘Very nicely!’”Meaghan ShawMedia Manager, <strong>ANZCA</strong>“ The absence of mechanicalmoving parts, precisionengineering <strong>and</strong> attention todetail resulted in a ventilatorwith long-term reliability <strong>and</strong>legendary success.”Opposite page: A younger Dr Duncan Campbellwith a Campbell ventilator. This page:Dr Campbell taking possession of the firstCampbell ventilator.27