M.-S. Fletcher, P.I. Moreno / Quaternary International 253 (2012) 32e46 3712 ka, peak<strong>in</strong>g at w8.5 ka and decreas<strong>in</strong>g toward 4 ka (Fig. 3a).Depositional hiatuses effectively term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>the</strong> record at w4 ka.3.2.3. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Alps glacier dynamicsThe temperate glaciers of New Zealand are sensitive to climatechange, although <strong>the</strong>re is some debate over what component ofclimate exerts <strong>the</strong> greatest <strong>in</strong>fluence over changes <strong>in</strong> glacier massbalance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region, with both temperature and precipitationpurported as <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ant control (Fitzharris et al., 1992;Anderson and Mack<strong>in</strong>tosh, 2006; Purdie et al., 2011). A significantrelationship between <strong>the</strong> strength of SWW flow and glacialmass balance was observed by Fitzharris et al. (1992) and it is clearthat westerly derived precipitation is an important factor <strong>in</strong> glacialdynamics <strong>in</strong> this region. A substantial body of work has beendevoted to establish<strong>in</strong>g a chronology of glacial fluctuations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Alps that reveals multi-millennial trends that most likelyreflect both precipitation and temperature effects (e.g. Gellatlyet al., 1988; Denton and Hendy, 1994; Fitzsimons, 1997; Barrowset al., 2007; McCarthy et al., 2008; Schaefer et al., 2009). A salientfeature of <strong>the</strong> glacial record (Fig. 3b) is a deep glacial recessionbetween w11 and 7 ka, which Shulmeister et al. (2004) arguereflects weak westerly flow across <strong>the</strong> region effectively starv<strong>in</strong>gglaciers of moisture. Increased westerly flow and/or lowertemperatures are sufficient to account for widespread and welladvanced glaciation between 14 and 11 ka and for neoglaciations<strong>in</strong>ce 7 ka (Moreno et al., 2009; Rojas and Moreno, 2010;Shulmeister et al., 2010).3.2.4. SummaryClear multi-millennial trends are evident <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> palaeoenvironmentaldata from New Zealand’s South Island: 14e11,11e8, 7.5e4.5, and 4.5e0 ka. The period between 14 and 11 ka ischaracterised by relatively high aquatic pollen content at OkaritoBog and glacial advances <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Alps, likely reflect<strong>in</strong>ga comb<strong>in</strong>ation of cool temperatures and strong westerly flow over<strong>the</strong> region. Between 11 and 8 ka, aquatic pollen content decl<strong>in</strong>essubstantially at Okarito Bog on <strong>the</strong> west coast and precipitation<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> Otago to a maximum at w8.5 ka. Anti-phas<strong>in</strong>g of westand east precipitation anomalies is consistent with <strong>the</strong> modernrelationship between South Island ra<strong>in</strong>fall and westerly w<strong>in</strong>d speedand <strong>the</strong> lack of (or very much limited) glacial advance at this time iscontemporaneous with weak westerly flow. A comb<strong>in</strong>ation ofmaximum Holocene aquatic pollen content at Okarito Bog anddecreas<strong>in</strong>g precipitation east of <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Alps <strong>in</strong> Otago,contemporaneous with renewed glaciation, suggests an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>westerly flow over <strong>the</strong> South Island between 7.5 and 4.5 ka. After4.5 ka, aquatic pollen content <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Okarito record shows a gradualdecl<strong>in</strong>e toward <strong>the</strong> present; suggest<strong>in</strong>g a possible decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> westerlyflow over <strong>the</strong> region, while, <strong>in</strong> contrast, <strong>the</strong> spread of <strong>the</strong>podocarpaceous tree Dacrydium cupress<strong>in</strong>um recorded acrossSouthland and Otago (South Island New Zealand) has been <strong>in</strong>terpretedas <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> westerly flow across <strong>the</strong> regionafter ca. 3 ka (McGlone et al., 1993).4. Sou<strong>the</strong>rn South America4.1. Present environmentSouth America stretches from north of <strong>the</strong> equator to 55 S,transgress<strong>in</strong>g a broad range of climatic zones, from warm equatorialto cold sub-Antarctic. In <strong>the</strong> zone of westerly <strong>in</strong>fluence, largeamounts of year-round ra<strong>in</strong>fall <strong>in</strong>undate areas west of <strong>the</strong> Andessouth of w38 S, while <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ra<strong>in</strong>-shadow east of <strong>the</strong> Andes, subhumidto semi-arid conditions result from persistent foehnw<strong>in</strong>ds. Abundant precipitation of westerly orig<strong>in</strong> susta<strong>in</strong>stemperate ra<strong>in</strong>forests on <strong>the</strong> Pacific side of <strong>the</strong> Patagonian Andes(<strong>the</strong> region south of 40 S <strong>in</strong> South America). Climatic segregation of<strong>the</strong> vegetation has led to <strong>the</strong> recognition of Valdivian, North Patagonian,and sub-Antarctic ra<strong>in</strong>forest communities <strong>in</strong> Patagoniaalong a gradient of <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g precipitation and w<strong>in</strong>d speeds, lowertemperatures and length of <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g season. Vegetation east of<strong>the</strong> Andes is dom<strong>in</strong>ated by <strong>the</strong> sub-humid to semi-arid PatagonianSteppe to <strong>the</strong> east as moisture decreases. Seasonal forc<strong>in</strong>g drives<strong>the</strong> SWW north (south) <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter (summer) relative to <strong>the</strong>ir coreregion of strongest w<strong>in</strong>d speeds (w50 S), result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a w<strong>in</strong>ter(summer) dom<strong>in</strong>ant ra<strong>in</strong>fall climate north (south) of w50 S.4.2. Palaeoenvironmental records4.2.1. Lake-levels4.2.1.1. West of <strong>the</strong> Andes e central Chile. Laguna Aculeo is located<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mediterranean climate zone of central Chile toward <strong>the</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn limits of <strong>the</strong> zone of westerly <strong>in</strong>fluence (33 S; Fig. 1a), anarea <strong>in</strong> which local precipitation is positively correlated withwesterly w<strong>in</strong>d speed (Fig. 1). The hydrologic balance of this relativelyclosed-bas<strong>in</strong> lake is dependent on <strong>the</strong> westerlies for recharge(Jenny et al., 2003). A precipitation curve spann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> last 10,000years has been derived from changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> lake-level of LagunaAculeo through this time that is characterised by <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>gsequence (Fig. 4f; Jenny et al., 2003): low effective precipitationbetween 10 and 8.6 ka; a slight <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> precipitation at 8.6 ka;a marked <strong>in</strong>crease at 5.6 ka that persists until 3 ka; after whicha variable and slightly <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g precipitation regime prevails until<strong>the</strong> present.Abarzúa et al. (2004) present stratigraphic evidence from LagoTahui (w43 S), a small closed-bas<strong>in</strong> lake located <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>termora<strong>in</strong>aldepression <strong>in</strong> east-central Isla Grande de Chiloé, NWPatagonia, a region <strong>in</strong> which precipitation is strongly correlated withwesterly w<strong>in</strong>d speed. The record <strong>in</strong>cludes piston cores obta<strong>in</strong>edalong a bathymetric transect, correlated on <strong>the</strong> basis of tephra layersand radiocarbon dates. Cores collected from <strong>the</strong> shallow portion of<strong>the</strong> lake revealed a basal silty gyttja overla<strong>in</strong> by woody gyttja (with>5 cm diameter tree trunks and branches), overla<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> turn bycoarseorganic detritus gyttja, and gyttja until <strong>the</strong> present. The authors<strong>in</strong>terpreted <strong>the</strong>se data as evidence for a regressive lake phase thatled to <strong>the</strong> centripetal expansion of a swamp forest environment at<strong>in</strong>termediate depths <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> lake, followed by a transgressive phaseand persistence of <strong>the</strong> lake until today (Abarzúa et al., 2004). Theavailable chronology <strong>in</strong>dicates that lake-levels <strong>in</strong> Lago Tahuirema<strong>in</strong>ed stationary below <strong>the</strong> modern elevation between 11.5 and7.8 ka, imply<strong>in</strong>g a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> regional precipitation delivered by <strong>the</strong>SWW dur<strong>in</strong>g that time (Abarzúa et al., 2004).4.2.1.2. East of <strong>the</strong> Andes e Argent<strong>in</strong>e Patagonia. Lago Cardiel isa deep and much studied closed-bas<strong>in</strong> lake located with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dryPatagonian Steppe of Argent<strong>in</strong>a (49 S; Fig. 1a), a region receiv<strong>in</strong>g aslittle as 150 mm of annual ra<strong>in</strong>fall (Markgraf et al., 2003; Gilli et al.,2005a; Ariztegui et al., 2009). The site lies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ra<strong>in</strong>-shadow eastof <strong>the</strong> Andes Cordillera close to <strong>the</strong> present-day zone of maximumSWW speeds (50 S), and displays a negative correlation betweenzonal w<strong>in</strong>d strength and local precipitation that results fromsignificant evaporative moisture loss as dry foehn w<strong>in</strong>ds stripmoisture from <strong>the</strong> region under strong westerly flow (Fig. 1b;Garreaud, 2007). A recent lake-level reconstruction from LagoCardiel reveals substantial lake-level changes s<strong>in</strong>ce 14 ka thatreflect changes <strong>in</strong> precipitation and evaporation (Ariztegui et al.,2009) (Fig. 4a). The lake was low between 14 and 12.3 ka, andwas followed by an abrupt transgressive phase that led to higherthan-modernlake-levels between w11e8 ka, represent<strong>in</strong>ga w100 m <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> lake-level and reflect<strong>in</strong>g a significant change

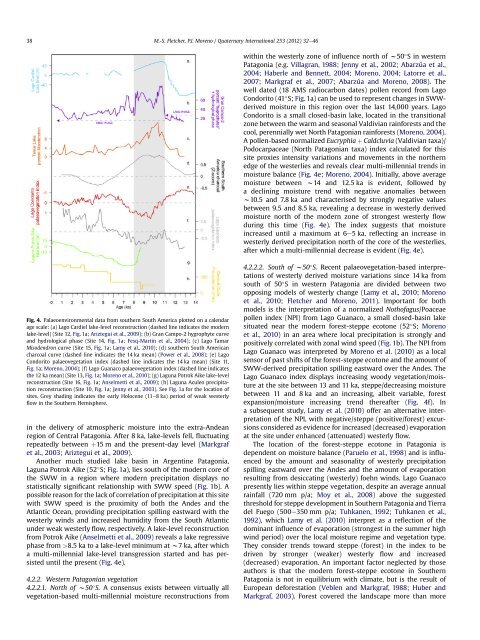

38M.-S. Fletcher, P.I. Moreno / Quaternary International 253 (2012) 32e46with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> westerly zone of <strong>in</strong>fluence north of w50 S <strong>in</strong> westernPatagonia (e.g. Villagran, 1988; Jenny et al., 2002; Abarzúa et al.,2004; Haberle and Bennett, 2004; Moreno, 2004; Latorre et al.,2007; Markgraf et al., 2007; Abarzúa and Moreno, 2008). Thewell dated (18 AMS radiocarbon dates) pollen record from LagoCondorito (41 S; Fig. 1a) can be used to represent changes <strong>in</strong> SWWderivedmoisture <strong>in</strong> this region over <strong>the</strong> last 14,000 years. LagoCondorito is a small closed-bas<strong>in</strong> lake, located <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> transitionalzone between <strong>the</strong> warm and seasonal Valdivian ra<strong>in</strong>forests and <strong>the</strong>cool, perennially wet North Patagonian ra<strong>in</strong>forests (Moreno, 2004).A pollen-based normalized Eucryphia þ Caldcluvia (Valdivian taxa)/Podocarpaceae (North Patagonian taxa) <strong>in</strong>dex calculated for thissite proxies <strong>in</strong>tensity variations and movements <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnedge of <strong>the</strong> westerlies and reveals clear multi-millennial trends <strong>in</strong>moisture balance (Fig. 4e; Moreno, 2004). Initially, above averagemoisture between w14 and 12.5 ka is evident, followed bya decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g moisture trend with negative anomalies betweenw10.5 and 7.8 ka and characterised by strongly negative valuesbetween 9.5 and 8.5 ka, reveal<strong>in</strong>g a decrease <strong>in</strong> westerly derivedmoisture north of <strong>the</strong> modern zone of strongest westerly flowdur<strong>in</strong>g this time (Fig. 4e). The <strong>in</strong>dex suggests that moisture<strong>in</strong>creased until a maximum at 6e5 ka, reflect<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>westerly derived precipitation north of <strong>the</strong> core of <strong>the</strong> westerlies,after which a multi-millennial decrease is evident (Fig. 4e).Fig. 4. Palaeoenvironmental data from sou<strong>the</strong>rn South America plotted on a calendarage scale: (a) Lago Cardiel lake-level reconstruction (dashed l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong> modernlake-level) (Site 12, Fig. 1a; Ariztegui et al., 2009); (b) Gran Campo-2 hygrophyte curveand hydrological phase (Site 14, Fig. 1a; Fesq-Mart<strong>in</strong> et al., 2004); (c) Lago TamarMisodendron curve (Site 15, Fig. 1a; Lamy et al., 2010); (d) sou<strong>the</strong>rn South Americancharcoal curve (dashed l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong> 14 ka mean) (Power et al., 2008); (e) LagoCondorito palaeovegetation <strong>in</strong>dex (dashed l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong> 14 ka mean) (Site 11,Fig. 1a; Moreno, 2004); (f) Lago Guanaco palaeovegetation <strong>in</strong>dex (dashed l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>dicates<strong>the</strong> 12 ka mean) (Site 13, Fig. 1a; Moreno et al., 2010); (g) Laguna Potrok Aike lake-levelreconstruction (Site 16, Fig. 1a; Anselmetti et al., 2009); (h) Laguna Aculeo precipitationreconstruction (Site 10, Fig. 1a; Jenny et al., 2003). See Fig. 1a for <strong>the</strong> location ofsites. Grey shad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong> early Holocene (11e8 ka) period of weak westerlyflow <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere.<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> delivery of atmospheric moisture <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> extra-Andeanregion of Central Patagonia. After 8 ka, lake-levels fell, fluctuat<strong>in</strong>grepeatedly between þ15 m and <strong>the</strong> present-day level (Markgrafet al., 2003; Ariztegui et al., 2009).Ano<strong>the</strong>r much studied lake bas<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> Argent<strong>in</strong>e Patagonia,Laguna Potrok Aike (52 S; Fig. 1a), lies south of <strong>the</strong> modern core of<strong>the</strong> SWW <strong>in</strong> a region where modern precipitation displays nostatistically significant relationship with SWW speed (Fig. 1b). Apossible reason for <strong>the</strong> lack of correlation of precipitation at this sitewith SWW speed is <strong>the</strong> proximity of both <strong>the</strong> Andes and <strong>the</strong>Atlantic Ocean, provid<strong>in</strong>g precipitation spill<strong>in</strong>g eastward with <strong>the</strong>westerly w<strong>in</strong>ds and <strong>in</strong>creased humidity from <strong>the</strong> South Atlanticunder weak westerly flow, respectively. A lake-level reconstructionfrom Potrok Aike (Anselmetti et al., 2009) reveals a lake regressivephase from >8.5 ka to a lake-level m<strong>in</strong>imum at w7 ka, after whicha multi-millennial lake-level transgression started and has persisteduntil <strong>the</strong> present (Fig. 4e).4.2.2. Western Patagonian vegetation4.2.2.1. North of w50 S. A consensus exists between virtually allvegetation-based multi-millennial moisture reconstructions from4.2.2.2. South of w50 S. Recent palaeovegetation-based <strong>in</strong>terpretationsof westerly derived moisture variations s<strong>in</strong>ce 14 ka fromsouth of 50 S <strong>in</strong> western Patagonia are divided between twooppos<strong>in</strong>g models of westerly change (Lamy et al., 2010; Morenoet al., 2010; Fletcher and Moreno, 2011). Important for bothmodels is <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation of a normalized Nothofagus/Poaceaepollen <strong>in</strong>dex (NPI) from Lago Guanaco, a small closed-bas<strong>in</strong> lakesituated near <strong>the</strong> modern forest-steppe ecotone (52 S; Morenoet al., 2010) <strong>in</strong> an area where local precipitation is strongly andpositively correlated with zonal w<strong>in</strong>d speed (Fig. 1b). The NPI fromLago Guanaco was <strong>in</strong>terpreted by Moreno et al. (2010) as a localsensor of past shifts of <strong>the</strong> forest-steppe ecotone and <strong>the</strong> amount ofSWW-derived precipitation spill<strong>in</strong>g eastward over <strong>the</strong> Andes. TheLago Guanaco <strong>in</strong>dex displays <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g woody vegetation/moistureat <strong>the</strong> site between 13 and 11 ka, steppe/decreas<strong>in</strong>g moisturebetween 11 and 8 ka and an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g, albeit variable, forestexpansion/moisture <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g trend <strong>the</strong>reafter (Fig. 4f). Ina subsequent study, Lamy et al. (2010) offer an alternative <strong>in</strong>terpretationof <strong>the</strong> NPI, with negative/steppe (positive/forest) excursionsconsidered as evidence for <strong>in</strong>creased (decreased) evaporationat <strong>the</strong> site under enhanced (attenuated) westerly flow.The location of <strong>the</strong> forest-steppe ecotone <strong>in</strong> Patagonia isdependent on moisture balance (Paruelo et al., 1998) and is <strong>in</strong>fluencedby <strong>the</strong> amount and seasonality of westerly precipitationspill<strong>in</strong>g eastward over <strong>the</strong> Andes and <strong>the</strong> amount of evaporationresult<strong>in</strong>g from desiccat<strong>in</strong>g (westerly) foehn w<strong>in</strong>ds. Lago Guanacopresently lies with<strong>in</strong> steppe vegetation, despite an average annualra<strong>in</strong>fall (720 mm p/a; Moy et al., 2008) above <strong>the</strong> suggestedthreshold for steppe development <strong>in</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Patagonia and Tierradel Fuego (500e350 mm p/a; Tuhkanen, 1992; Tuhkanen et al.,1992), which Lamy et al. (2010) <strong>in</strong>terpret as a reflection of <strong>the</strong>dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong>fluence of evaporation (strongest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> summer highw<strong>in</strong>d period) over <strong>the</strong> local moisture regime and vegetation type.They consider trends toward steppe (forest) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dex to bedriven by stronger (weaker) westerly flow and <strong>in</strong>creased(decreased) evaporation. An important factor neglected by thoseauthors is that <strong>the</strong> modern forest-steppe ecotone <strong>in</strong> Sou<strong>the</strong>rnPatagonia is not <strong>in</strong> equilibrium with climate, but is <strong>the</strong> result ofEuropean deforestation (Veblen and Markgraf, 1988; Huber andMarkgraf, 2003). Forest covered <strong>the</strong> landscape more than more