Army - Stimulating Simulation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

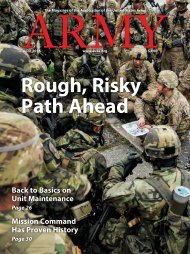

Command sergeants major work<br />

on problems during a course at<br />

Fort Leavenworth, Kan.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Jonathan ‘Jay’ Koester<br />

Accreditation of the academy, which has graduated more<br />

than 120,000 soldiers since its founding in 1972, is “long<br />

overdue,” Dailey said. “For years, we’ve been providing excellent<br />

training to our soldiers by way of tactical and technical<br />

education, but we haven’t done them justice in regards to certifying<br />

those courses within the equivalent civilian certifications<br />

and college credits. <strong>Army</strong> University is going to help us<br />

accomplish that goal.”<br />

Representatives of about 80 colleges and universities attended<br />

a December symposium to talk about ways of getting<br />

more credit for soldiers for the professional education they receive<br />

and how to increase rigor in training. Another meeting<br />

is planned for June.<br />

Schools represented at the meeting are already involved<br />

with training soldiers, with some offering distance-learning<br />

courses for college credit and others operating on-post. One<br />

of the vexing and unresolved issues facing soldiers is that<br />

credits earned through <strong>Army</strong> training and from schools affiliated<br />

with the <strong>Army</strong> do not always transfer to other colleges<br />

and universities, especially prestigious four-year schools. Improving<br />

the academic standing of the classes available to soldiers<br />

is seen as a way of trying to resolve this problem.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Not Alone<br />

However, this is not an <strong>Army</strong>-only problem. Nonmilitary<br />

students transferring from community colleges to four-year<br />

schools face similar problems receiving full credit for courses<br />

already taken. A 2015 Pell Institute study on inequities in<br />

higher education in the U.S. says transferring from one college<br />

to another is one of the factors affecting equity in education.<br />

The report called for state governments and schools to<br />

“do more to ensure that students can transfer across higher<br />

education institutions without loss of academic credit.”<br />

Columbia University’s Community College Research Center<br />

reports that students who transfer credits in efforts to earn<br />

a bachelor’s degree are less likely to complete the degree and<br />

take longer to complete the degree if they do finish, a problem<br />

well-known to soldiers who<br />

move from post to post collecting<br />

college credits. Taking longer to<br />

complete a degree is part of a nationwide<br />

trend that goes beyond<br />

the <strong>Army</strong>. A November report<br />

from the National Student Clearinghouse<br />

Research Center found<br />

just 53 percent of students who<br />

enrolled in college in 2009 completed<br />

a degree within six years.<br />

There are gains in getting credit.<br />

For example, the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Prime<br />

Power School at Fort Leonard<br />

Wood, Mo., provides up to 38<br />

college credits in math, applied<br />

physics, mechanical engineering and electrical engineering for<br />

graduates, something possible because the instructors are professors<br />

from nearby Lincoln University. The partnership created<br />

at Prime Power is an example of what the <strong>Army</strong> wants<br />

to duplicate in other professional education courses.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> University is not a new idea. It was first raised in 1949<br />

by Lt. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, a former instructor and later<br />

commandant of the <strong>Army</strong>’s Command and General Staff College,<br />

who pushed the idea to the War Department’s Military<br />

Education Board as part of a postwar overhaul. The Air Force<br />

had created Air University in 1946, essentially for the same<br />

reasons the <strong>Army</strong> is considering today.<br />

“It was hoped that the re-designation would help to correct<br />

the numerous problems that plagued the pre-war military education<br />

system,” according to Air University’s official history.<br />

“The schools that comprised the old system had operated independently<br />

and were poorly coordinated in scope, doctrine<br />

and curriculum.” Marine Corps University was established in<br />

1989; like <strong>Army</strong>U, it includes professional education for both<br />

officers and enlisted personnel.<br />

It is no coincidence that the <strong>Army</strong>, like the Air Force, is<br />

undertaking a postwar transformation of its education system.<br />

“History reveals that some of the best and longest-lasting<br />

transformations in military education occur in the aftermath<br />

of sustained conflicts,” the white paper notes. “The <strong>Army</strong> today<br />

is a veteran force with real-world experience derived from<br />

years of sustained combat. This experience informs our judgment<br />

and gives us a deep appreciation for the complex and<br />

unpredictable challenges ahead.”<br />

Since the <strong>Army</strong> isn’t building a physical university, costs for<br />

the initiative are low: around $4 million in fiscal 2016 and $3.7<br />

million in FY 2017, according to the business plan estimate.<br />

Dailey said he hopes for quick improvements. “I want to<br />

accomplish these goals in 18 months,” he said of the effort to<br />

get the Sergeants Major Academy accredited. “That’s really<br />

aggressive, but I feel like we are 240 years behind on this.” ✭<br />

—Ferdinand H. Thomas II contributed to this report.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 29