NCC Magazine - Spring 2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SPRING <strong>2017</strong><br />

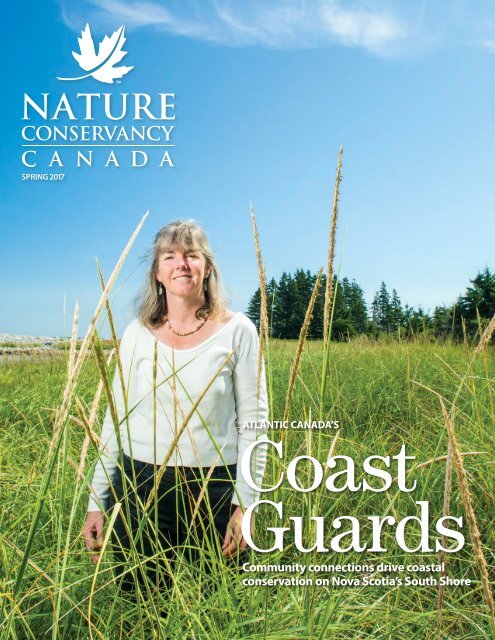

ATLANTIC CANADA’S<br />

Coast<br />

Guards<br />

Community connections drive coastal<br />

conservation on Nova Scotia’s South Shore

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong><br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

36 Eglinton Avenue West, Suite 400<br />

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4R 1A1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca<br />

Phone: 416.932.3202<br />

Toll-free: 800.465.0029<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

is the nation’s leading land conservation<br />

organization, working to protect our most<br />

important natural areas and the species<br />

they sustain. Since 1962, <strong>NCC</strong> and its partners<br />

have helped to protect 2.8 million acres (more<br />

than 1.1 million hectares), coast to coast.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is<br />

distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible for any calculations<br />

on saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed on Rolland Opaque paper, which<br />

contains 30% post-consumer fibre, is<br />

EcoLogo, Processed Chlorine Free certified<br />

and manufactured in Canada by Rolland<br />

using biogas energy. Printed in Canada with<br />

vegetable-based inks by Warrens Waterless<br />

Printing. This publication saved 29 trees and<br />

104,292 litres of water*.<br />

Design by Evermaven.<br />

COVER<br />

Danielle Robertson,<br />

Port Joli, Nova Scotia<br />

Photo by Aaron McKenzie Fraser.<br />

THIS PAGE<br />

Pointe Saint-Pierre, Quebec<br />

Photo by Mike Dembeck.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

GENERATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM<br />

*<br />

2 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Contents<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada SPRING <strong>2017</strong><br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

L-R, TOP TO BOTTOM: AARON MCKENZIE FRASER. SCOUTS CANADA. <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Hope and optimism<br />

Conservation is an effort of hope and<br />

optimism in the face of what can<br />

seem like unsurmountable obstacles.<br />

But just as the flap of a butterfly’s wings can<br />

have a large effect, so too can the actions of<br />

a single person buoyed by hope and optimism<br />

lead to great things.<br />

In the early sixties, J. Bruce Falls, a young<br />

zoology professor at the University of Toronto,<br />

was one of a small group of hopeful optimists<br />

who founded the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>). “We were seeing that many of<br />

the areas that we were interested in…were<br />

disappearing or being degraded,” said Falls<br />

in an interview a few years ago. “We thought,<br />

we’d better do something about it.”<br />

This past December, Falls’s contributions<br />

to Canadian conservation were recognized<br />

when he was named a member of the Order<br />

of Canada — a true testament to the impact<br />

of his hopeful vision more than 50 years ago.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s president and CEO, John Lounds,<br />

was also recently recognized with the<br />

Museum of Nature’s 2016 Nature Inspiration<br />

Award. Lounds has guided <strong>NCC</strong> since 1997.<br />

His vision of <strong>NCC</strong> as a national conservation<br />

organization with offices in all 10 provinces<br />

has defined the scope of our work, and helped<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> evolve into Canada’s leading land<br />

conservation charity. We congratulate him<br />

and Bruce Falls on their recent awards.<br />

In the pages that follow, you’ll read stories<br />

about other hopeful, optimistic individuals,<br />

without whom <strong>NCC</strong>’s conservation achievements<br />

would not be possible. People like<br />

Danielle Robertson and Dirk van Loon, who<br />

believe in the importance of protecting the<br />

lands on which they live. We celebrate them,<br />

and we thank you for all you do to support<br />

our shared vision for a natural Canada.<br />

CBT<br />

Christine Beevis Trickett,<br />

Managing Editor<br />

8<br />

7 14<br />

14 Small Acts of<br />

Conservation<br />

Five ways you can help nature in your<br />

backyard or on your balcony<br />

16 Yellow Quill<br />

Prairie Preserve<br />

This grassland property in Manitoba<br />

bears traces of an ancient trade route<br />

17 Scouts Canada<br />

Backpack Essentials<br />

National youth commissioner<br />

Caitlin Piton’s backpack must-haves1<br />

18 Feature Story:<br />

Coastal Roots<br />

Conservation in Port Joli, Nova Scotia,<br />

begins with the community<br />

12 Eel-grass<br />

This member of the seagrass family is<br />

declining in many parts of its range<br />

14 Project Updates<br />

Four ways <strong>NCC</strong> staff are collaborating<br />

with ranchers and farmers in Manitoba,<br />

Saskatchewan, Alberta and B.C.<br />

16 Richard Ivey:<br />

Family Values<br />

The Ivey family’s leadership has inspired<br />

conservation across Canada<br />

18 Remembering<br />

Stuart McLean<br />

A special story about one of <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

conservation projects, à la Vinyl Cafe<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

Small Acts of<br />

Conservation<br />

Five things you can do right now to help<br />

nature in your backyard or on your balcony<br />

Many of us steward a small piece of Canada. It could be a recreational<br />

property or a few square metres in an urban backyard. While these<br />

places are not a wilderness or a wildlife preserve, they are all still a part<br />

of nature, and they have a role in conservation.<br />

Here’s a checklist of five small acts of conservation we can all<br />

take to help nature, which will also benefit you and your community.<br />

GETTY IMAGES.<br />

4 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

2<br />

4<br />

ISTOCK.<br />

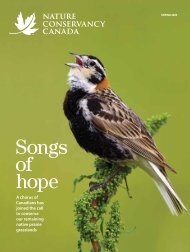

1Be for<br />

the birds<br />

The Baltimore oriole or<br />

scarlet tanager on your<br />

property today may have<br />

been in Venezuela when<br />

you were shoveling snow or<br />

skiing. Every year, billions of<br />

songbirds make the journey<br />

to Canada for one simple<br />

reason: the explosion of<br />

life that happens in our<br />

northern spring makes it a<br />

great place to raise a family.<br />

Sadly, migratory songbirds<br />

have been rapidly declining.<br />

While many species remain<br />

common, they are at risk<br />

because of steep population<br />

declines. For example,<br />

the wood thrush and barn<br />

swallow are both considered<br />

at risk because their populations<br />

in Canada have<br />

declined by more than<br />

75 per cent since 1970.<br />

You can help by creating<br />

migratory bird pit-stops<br />

on your property. Planting<br />

clusters of native shrubs or<br />

trees can provide important<br />

habitat. If every Canadian<br />

with a single-detached<br />

house provided just one<br />

small patch of vegetation for<br />

songbirds in their yard, we’d<br />

add more than 7 million new<br />

sites for nesting and resting.<br />

Soak it<br />

all in<br />

On many yards and<br />

properties, water no longer<br />

sits and soaks into the<br />

ground, but runs off roofs,<br />

driveways, fields and lawns<br />

into drains and eventually<br />

into our streams and lakes.<br />

One of the biggest issues for<br />

Canada’s freshwater is too<br />

much runoff, which carries<br />

sediments, nutrients and<br />

pollutants into our streams<br />

and lakes. This can clog<br />

streams with silt and cause<br />

algal blooms in even very<br />

big lakes, such as Lake Erie<br />

and Lake Winnipeg.<br />

Where you can, slow the<br />

flow. Hold water on your<br />

property in rain barrels, rain<br />

gardens, wetlands or other<br />

natural habitats. Make sure<br />

the water that leaves your<br />

property is as clean as it can<br />

be. Remember, the more<br />

water that infiltrates the<br />

ground on your property,<br />

the more you are helping<br />

to conserve Canada’s<br />

freshwater habitats.<br />

3Cover it up<br />

A study on the benefits of<br />

conserved forests by TD<br />

Bank Group and the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) found that an acre<br />

of conserved forest can<br />

provide up to $18,000 in<br />

important services, such as<br />

reducing floods, removing<br />

air pollution and sequestering<br />

carbon, every year.<br />

Not only are trees the<br />

original (and still the best)<br />

carbon capture and storage<br />

method ever developed,<br />

they literally create habitat<br />

in what was once thin air.<br />

When we fill that space<br />

above our heads with<br />

limb and leaf, we create<br />

new habitats.<br />

There are millions of places<br />

in our cities and around our<br />

homes that could support<br />

more trees. If you can, find<br />

a place to plant a native tree<br />

on your property, or support<br />

a forest restoration project<br />

at <strong>NCC</strong>. You’ll be helping<br />

create important habitats,<br />

and making the world<br />

a cooler place.<br />

Know<br />

your place<br />

Unfortunately, particularly<br />

for the eight in 10 Canadians<br />

who live in cities, we are<br />

losing our nature knowledge,<br />

and with it, an understanding<br />

of our connectedness<br />

to other living things and<br />

the natural world.<br />

The good news is that<br />

learning about nature<br />

is getting easier. While a<br />

walk through the woods<br />

or grasslands with an elder<br />

or experienced naturalist<br />

may still be the best way to<br />

learn, a few clicks on the<br />

internet can reveal not only<br />

the species in and around<br />

your home, but also how to<br />

identify them.<br />

Even learning about five<br />

new species a year can<br />

change the way you see the<br />

world. As you get to know<br />

wild things, they start to<br />

reveal themselves. What<br />

appears as a blanket of<br />

forest or prairie becomes<br />

a richer tapestry of life.<br />

Join us! This year’s Conservation<br />

Volunteers season launches April 24!<br />

conservationvolunteers.ca<br />

5Leave<br />

some wild<br />

Our challenge in Canada is<br />

that while we have the rare<br />

opportunity to protect some<br />

of the world’s last true<br />

wilderness in our northlands,<br />

we have lost significant<br />

amounts of our natural<br />

habitats in the south where<br />

most people live. This loss<br />

impacts both nature and<br />

the well-being of Canadians.<br />

We have nature in our cities<br />

and homes. It may not be<br />

the same nature that was<br />

there hundreds of years ago,<br />

but it can provide important<br />

habitat. There are hundreds<br />

of species that will share our<br />

space, if we provide room<br />

for them. This year, create or<br />

expand a small area of wild<br />

on your property and enjoy<br />

your nature neighbours.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 5

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

Learning about prairie skinks<br />

Visitors to this Manitoba property<br />

may still be able to catch a glimpse<br />

of a historic trade route.<br />

Yellow Quill<br />

Prairie Preserve<br />

This native mixed-grass prairie area in Manitoba conserves<br />

nature and our shared history of the land<br />

Ruffed grouse<br />

Long before European explorers and<br />

settlers arrived in North America,<br />

indigenous peoples had defined the<br />

most convenient routes to travel the landscape.<br />

Among them, the Yellow Quill Trail (named for<br />

Chief Yellow Quill of the Saulteaux First Nation<br />

during the late 1800s) connected Portage la<br />

Prairie, west of Winnipeg, with the Boundary<br />

Commission Trail, just past the western<br />

Saskatchewan border. Later, these trade routes<br />

were adopted by European settlers.<br />

Today, the Yellow Quill Prairie Preserve,<br />

south of Brandon in Manitoba, still bears faint<br />

traces of the Yellow Quill Trail. Here, the trail<br />

passes through a rolling, sandy prairie of<br />

mixed grasses, such as big and little bluestem,<br />

green needle grass and porcupine grass,<br />

interspersed with hazelnut, juniper, aspen, bur<br />

oak and white spruce.<br />

A NATURAL FAMILY LEGACY<br />

The Mooneys, fourth-generation descendants<br />

of the European pioneers who settled in the<br />

area in 1885, were the original owners of most<br />

of the lands: 1,440 acres (580 hectares) within<br />

the Yellow Quill project area. The family has<br />

leased the remaining 960 acres (390 hectares)<br />

from the provincial government.<br />

Over time, conversion of the neighbouring<br />

native grasslands all but eliminated these<br />

once-large tracts of native grasslands. But the<br />

Mooneys knew the ecological value of their<br />

lands. After being approached by <strong>NCC</strong>, they<br />

decided to fulfill the wishes of their departed<br />

father by selling the land to <strong>NCC</strong> in the<br />

hopes that their mixed-grass prairie would<br />

not be lost.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> purchased the lands from the<br />

Mooney family in 1999. Shortly after completing<br />

the purchase, <strong>NCC</strong> developed a management<br />

plan that incorporated traditional cattle<br />

grazing practices to maintain biodiversity.<br />

LANDSCAPE: <strong>NCC</strong>. SKINK: <strong>NCC</strong>. GROUSE: ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

6 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

Today, these areas continue to shelter native<br />

mixed-grass prairie.<br />

In 2016, <strong>NCC</strong>’s Manitoba Region expanded<br />

the original project with the addition of<br />

a further 320 acres (130 hectares).<br />

A UNIQUE LANDSCAPE<br />

These lands, nestled along the western<br />

boundary of the Assiniboine Delta in south<br />

central Manitoba, are representative of the<br />

vast prairies that once extended across<br />

southern Manitoba. The landforms resulted<br />

from the deposits of sediment in the delta,<br />

where the Assiniboine River flowed into<br />

glacial Lake Agassiz. As the waters receded<br />

about 10,000 years ago, the sediments were<br />

shaped into sandhill complexes, which remain<br />

the dominant feature on the landscape today.<br />

The unique sandhill landscape and occasional<br />

open dunes are some of the last refuges<br />

in the province where rare sandhill species<br />

exist. Over time, lack of disturbance has caused<br />

the historically open dunes to stabilize with<br />

the roots of plants and grasses. <strong>NCC</strong> staff are<br />

working to implement management programs<br />

that promote the stewardship and recovery of<br />

dune complexes, an important and increasingly<br />

rare ecosystem type in Manitoba.<br />

Visitors to the property may spot elk,<br />

coyote, moose, deer and fox. The Yellow<br />

Quill Prairie Preserve is a preferred site for<br />

birdwatchers wishing to see red-tailed hawk,<br />

ruffed grouse, sharp-tail grouse and mountain<br />

bluebird. It’s also important habitat for the<br />

endangered prairie skink.<br />

1<br />

5<br />

4<br />

Scout’s honour<br />

Caitlyn Piton, national youth commissioner & chair of<br />

Scouts Canada’s National Youth Network, shares her<br />

backpack must-haves<br />

3<br />

2<br />

ITEMS: JUAN LUNA. CAITLYN PITON: SCOUTS CANADA.<br />

TRAILS<br />

Length: approximately 4.5 km of access trails<br />

Difficulty: easy<br />

Terrain: rolling sandhills and native grasslands<br />

GETTING THERE<br />

The property is located 20 kilometres southeast<br />

of Brandon and two kilometres north of the<br />

junction of the Souris and Assiniboine rivers. It<br />

abuts the western boundary of the Canadian<br />

Forces Base Shilo. Visitors are asked to call<br />

1-866-683-6934 prior to visiting to ensure land<br />

management activities are not active on-site.A<br />

DOWNLOAD THE TRAIL MAP<br />

Visit natureconservancy.ca/yellowquill<br />

to download a trail map and directions.<br />

1. BEEF JERKY I tend to<br />

get hungry fairly easily,<br />

so a quick snack is<br />

a must or I might get<br />

grumpy (as my<br />

team knows).<br />

2. WATER FILTER<br />

This is much easier<br />

than having to carry<br />

around bottles of water,<br />

if there are streams along<br />

your way.<br />

3. LOOSE LEAF TEA I don’t think I could<br />

go a day without tea. It’s nice to have<br />

something comforting,<br />

especially if it’s raining<br />

(which it does a lot<br />

in Vancouver, where<br />

I’m from).<br />

4. FIRST AID KIT<br />

I’m a klutz, so this is<br />

an absolute must.<br />

5. KNIFE I have a knife<br />

that I absolutely love. It<br />

has engraving on it from some<br />

of the work I’ve done with Scouts<br />

Canada and is the most useful thing<br />

I’ve ever received!1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 7

Coastal<br />

roots<br />

A love for nature that runs<br />

as deep as the waters off<br />

Nova Scotia’s South Shore<br />

drives coastal conservation<br />

from the grassroots up<br />

BY Sandra Phinney<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY Aaron McKenzie Fraser<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

8 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Danielle Robertson has<br />

had a love affair with nature in<br />

general, and Port Joli, Nova<br />

Scotia, in particular, for as long as she can<br />

remember. Her roots run deep, as do those<br />

of her husband, Charles. The land they live<br />

on in Port Joli, nestled along Nova Scotia’s<br />

South Shore, has been in the family since 1786,<br />

when early settlers fished and farmed here.<br />

“You can still see old fence posts<br />

that were used to build platforms on the<br />

coastal marsh where they stored the hay,”<br />

says Robertson.<br />

Yet the places their ancestors knew and<br />

cared for over generations are increasingly<br />

under threat from habitat loss, climate change<br />

and the encroachment of invasive species,<br />

such as European green crab. Given that<br />

Canada’s East Coast is projected to experience<br />

rising sea levels of up to one metre by the end<br />

of the century, it comes as no surprise that the<br />

potential impacts of this latter threat on our<br />

coastal ecosystems and coastal communities<br />

are staggering.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has conserved close to 340 kilometres of marine coastal habitat in Canada, including here at Port Joli, Nova Scotia.<br />

For an interactive map showing the timeline of <strong>NCC</strong>’s work in Port Joli, visit: natureconservancy.ca/port-joli<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 9

One of the ways to safeguard these places,<br />

for the people and species that live in them, is<br />

for conservation organizations like the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) to work with<br />

people on the ground at the grassroots level.<br />

Support from local champions like Danielle<br />

Robertson and her family — people who are<br />

innately tied to the land and its history — is<br />

critical in helping ensure a future for these<br />

coastal landscapes.<br />

Robertson has spent decades digging her<br />

roots deeper, getting to know the natural<br />

and human history of Port Joli. Shortly after<br />

graduating from Mount Saint Vincent University<br />

in 1989, Robertson was hired to do research<br />

for the nearby Thomas Raddall Provincial<br />

Park, which further fuelled her passion for the<br />

region. In the process, she researched the<br />

park’s Mi’kmaq clam middens (areas where<br />

First Nations would dispose of clam shells<br />

after harvesting them), evidence of a rich<br />

human history dating back thousands of years.<br />

“I got obsessed with the sites,” she says,<br />

“and I also got serious about conservation.”<br />

Robertson was proud that Port Joli and<br />

neighbouring Port L’Hebert had four parks,<br />

It’s getting more and more important that Canada be<br />

the kind of country that protects the flora and fauna,<br />

and where you can go out into the wild and explore.<br />

DIRK VAN LOON (CENTRE, ABOVE ) BECAME A LAND DONOR AFTER DANIELLE ROBERTSON (OPENING<br />

SPREAD) OPENED THE DOOR TO WORKING WITH <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

a nature reserve and three migratory bird<br />

sanctuaries that were protected from development<br />

and managed by national and provincial<br />

government agencies — signs of the area’s<br />

natural and cultural significance. Yet she often<br />

thought how wonderful it would be for her<br />

family and next generations if even more<br />

land in the region could be protected from<br />

extensive housing developments, quarries<br />

and clear cutting.<br />

Thirteen years ago, she and Charles<br />

contacted <strong>NCC</strong>. Would the organization be<br />

interested in buying a piece of the Robertson<br />

family’s property if they donated a parcel?<br />

Shortly after opening the door, Robertson also<br />

provided contact information to <strong>NCC</strong> staff for<br />

other landowners in hopes that, down the<br />

road, <strong>NCC</strong> could help secure other lands in<br />

the area. And that’s exactly what transpired.<br />

Local champions<br />

Craig Smith, Nova Scotia program director with<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>, says that a number of factors influence<br />

whether the land conservation organization<br />

pursues work in a natural area or not.<br />

“One of them is: do you have local champions?<br />

When the Robertsons placed the call to<br />

us, it happened to coincide with <strong>NCC</strong> completing<br />

a survey of this region,” says Smith. <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

staff had identified southwest Nova Scotia<br />

as one of the areas that stood out as being<br />

particularly ecologically important because of<br />

its forests, diversity and rich coastal habitats.<br />

Another of the many special features of<br />

the area is that endangered mainland moose<br />

living in the Tobeatic Wilderness Area migrate<br />

to the Port Joli peninsula in the summer<br />

— perhaps for the cooler climate and for the<br />

salt content of the coastal marshes. Also, this<br />

10 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

AERIAL: MIKE DEMBECK.<br />

region is part of the South Shore (Port Joli<br />

sector) Important Bird Area, which provides<br />

valuable habitat for migrating shorebirds<br />

and waterfowl, and nesting habitat for the<br />

endangered piping plover.<br />

“Property owners like Danielle can be<br />

extremely helpful to bridge the divide and<br />

create a more nuanced understanding among<br />

other landowners about who we are and<br />

what we do,” Smith says.<br />

That knowledge of <strong>NCC</strong> came in handy<br />

when Robertson approached a neighbouring<br />

landowner, Dirk van Loon, who had moved<br />

to the area from the United States in 1969. He<br />

and his wife bought an old farm in Port Joli,<br />

where he homesteaded, wrote books and<br />

started a magazine.<br />

“Where I grew up back in the U.S. is now<br />

all developed. There is no wilderness there<br />

anymore,” says van Loon. “So it’s getting more<br />

and more important that Canada be the kind<br />

of country that protects the flora and fauna, and<br />

where you can go out into the wild and explore.”<br />

Many years ago, van Loon and two other<br />

like-minded families acquired 180 acres (70<br />

hectares) in Port Joli on the spectacular Sandy<br />

Bay Beach. They wanted to ensure the beach<br />

remained natural and undeveloped. Van Loon<br />

later handed down his portion of the beach to<br />

his son, and together, because of a shared ethic,<br />

the group of Sandy Bay landowners worked<br />

with <strong>NCC</strong> to bring the beach into conservation.<br />

In 2015, van Loon sold a substantial piece of<br />

his land in the same area to <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

The lands around Sandy Bay Beach have<br />

humid coastal forests, rare lichens and lots of<br />

Craig Smith, <strong>NCC</strong>’s Nova Scotia program director, surveys the coastline.<br />

wildlife. “I blame Danielle Robertson for<br />

getting us involved,” van Loon jokes. “She<br />

opened the door to working with <strong>NCC</strong>.”<br />

Now, <strong>NCC</strong> protects 1,627 acres (658<br />

hectares) in Port Joli and its surrounding<br />

region, thanks to landowners such as the<br />

Robertsons and van Loon, who know the<br />

land on which they live is a special place.<br />

Historical connections<br />

It’s now clear that this understanding of the<br />

area’s ecological richness was shared by First<br />

Nations communities that lived here thousands<br />

of years ago. Port Joli was a cultural landscape,<br />

where people expressed their customs as well<br />

as made a living.<br />

“In Port Joli, we’ve found hard evidence<br />

that the place was an ecological node (a place<br />

of special ecological diversity and productivity),”<br />

says Matthew Betts, PhD, and curator,<br />

eastern archaeology with the Canadian Museum<br />

of History. “The Mi’kmaq lived on the coast<br />

all year round, as opposed to the traditional<br />

model of spending winters in the interior and<br />

summers on the coast.”<br />

In Nova Scotia, where 90 per cent of<br />

the coastline is privately owned, these local<br />

connections with people who know the<br />

land are ever more important if these special<br />

places are to be protected. As <strong>NCC</strong> continues<br />

to conserve lands and waters across the<br />

country, working with people on the ground<br />

who have deep roots, like the Robertsons<br />

and van Loon, provides an excellent model<br />

of what can be done if Canadians<br />

work together.1<br />

PRESSURE RISING ON<br />

CANADA’S COASTS<br />

With over a quarter of a million<br />

kilometres of beaches, rocky shores,<br />

salt marshes, seagrass meadows and<br />

sea cliffs, Canada has more coastline<br />

than the U.S. and Russia combined.<br />

Canada’s coasts are the ecological<br />

interface between land and sea, and<br />

are equally essential for shorebirds<br />

and the close to 1,100 fish species<br />

that live in nearshore waters.<br />

Many coastal habitats are very sensitive.<br />

In addition to direct pressures, such<br />

as unsustainable recreational uses and<br />

invasive species, the health of coasts<br />

often reflects the health of surrounding<br />

lands and marine waters.<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

Climate change is increasing the<br />

pressures on our coasts. Rising sea<br />

levels and extreme storm surges are<br />

changing the forces that have shaped<br />

coastal ecosystems. Across Canada,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> is incorporating climate change<br />

impacts into our conservation actions<br />

to increase the resiliency of coastal<br />

habitats and to buffer coastal<br />

communities from the impacts<br />

of climate change.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Eel-grass<br />

This unassuming species plays a major role in Canada’s coastal ecosystems<br />

MARTIN ALMQVIST/ALAMY/ALL CANADA PHOTOS.<br />

12 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Eel-grass, a type of seagrass, first evolved as an aquatic algae,<br />

moved to land and then returned to the ocean. Its long,<br />

bright-green blades resemble underwater ribbons. The<br />

plant’s complex root system allows it to anchor itself to the floors of<br />

shallow bays, coves, lagoons and estuaries. By filtering and trapping<br />

sediment, pollutants and nutrients, the species helps improve water<br />

quality. Eel-grass beds support many marine invertebrates and provide<br />

spawning and nursery habitat for numerous fish, resulting in<br />

important feeding areas for marine birds and mammals.<br />

STRUCTURE AND REPRODUCTION<br />

Often mistaken for seaweed, eel-grass differs from it in several ways. For example,<br />

unlike seaweed, eel-grass roots not only anchor the plants, they also absorb<br />

nutrients. Eel-grass also has flowers and veins.<br />

Eel-grasses reproduce in two ways: asexually, through cloning, and sexually,<br />

by producing seeds. Like land grasses, eel-grass shoots are interconnected through<br />

an underground rhizome (a large, root-like structure) network. As rhizomes spread,<br />

they create new shoots that are clones of one another.<br />

To reproduce sexually, male eel-grass flowers release pollen into the water,<br />

which is then moved by underwater currents. The pollen grains, which are<br />

the longest of any plant species in the world, then fertilize female flowers and<br />

produce seeds.<br />

A SENSITIVE SPECIES<br />

Eel-grass is highly susceptible to human interference. Shade from docks, floating log<br />

booms and algae also threaten this species. “Wasting disease,” caused by a marine<br />

slime mold, affects some Atlantic populations. A relatively recent threat to eel-grass<br />

is the European green crab — an invasive species that arrived in Atlantic Canada<br />

in the 1950s in the ballast water of ships — which cuts the grasses while digging in<br />

sediment for food.<br />

FACT SHEET<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME<br />

Zostera marina<br />

SIZE AND WEIGHT<br />

Can reach lengths of up to 1 m.<br />

RANGE<br />

North America’s Atlantic and Pacific<br />

coasts, as well as Hudson Bay.<br />

POPULATION TREND<br />

Globally, eel-grass meadows have<br />

declined on average by about<br />

seven per cent per year since 1990.<br />

Some declines along Canada’s B.C.<br />

coast could have resulted from the<br />

introduction of the non-native Pacific<br />

oyster to the wild. In Newfoundland<br />

and Labrador, eel-grass abundance<br />

has increased over the past decade.<br />

STATUS IN CANADA<br />

No official status. NatureServe ranks it<br />

as imperilled in Ontario and Manitoba,<br />

and vulnerable in Quebec and Newfoundland<br />

and Labrador.<br />

DID YOU KNOW?<br />

Seagrasses are estimated to be<br />

responsible for 15 per cent of the total<br />

carbon storage in the ocean, even<br />

though they occupy only 0.2 per cent<br />

of the oceans.<br />

SCOTT LESLIE/MINDEN PICTURES.<br />

CONSERVATION EFFORTS<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) is protecting eel-grass habitat along<br />

Canada’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts. In 2014, staff in Nova Scotia partnered with<br />

the Province of Nova Scotia and used aircraft and satellite imagery to map and<br />

monitor eel-grass beds in the Pugwash Estuary and Musquodoboit Harbour. The<br />

following year, <strong>NCC</strong> trapped European green crabs at the Pugwash Estuary to<br />

determine this invasive species’ population size. In addition, <strong>NCC</strong> has acquired<br />

valuable coastal land along Nova Scotia’s Northumberland Strait, which includes<br />

important eel-grass beds.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has also protected upland areas around estuaries in New Brunswick, such<br />

as those at Tabusintac, where research is being conducted on eel-grass. Meanwhile,<br />

in Quebec's Malbaie salt marsh, <strong>NCC</strong> has conserved a property that shelters an<br />

eel-grass colony. Black ducks make stopovers here during their migration, to feed<br />

on the plant.<br />

In British Columbia, <strong>NCC</strong> has helped restore eel-grass populations in the<br />

Campbell River Estuary on Baikie Island by replanting native vegetation in<br />

marshes along rivers and streams. <strong>NCC</strong> staff have also identified eel-grass beds<br />

as a priority habitat for coastal conservation projects, such as Grace Islet,<br />

Clayoquot Island and the Gullchucks Conservation Area.1<br />

CRABBY TIME<br />

Green crabs are an invasive species that<br />

is now established in many locations<br />

in North America and is still expanding<br />

its range.<br />

Learn more at natureconservancy.ca/<br />

green-crab<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 13

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

1<br />

Cows and conservation<br />

ACROSS CANADA<br />

2<br />

3<br />

1<br />

4<br />

WANT TO LEARN MORE?<br />

Visit natureconservancy.ca/en/where-we-work<br />

to learn more about these and other <strong>NCC</strong> projects.<br />

What do cows and conservation have in common? The Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) membership in the Canadian<br />

Roundtable for Sustainable Beef (CRSB) is just one example of the<br />

many ways that <strong>NCC</strong> has established tangible working relationships<br />

with farmers and ranchers.<br />

The CRSB, a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on advancing<br />

sustainability within the Canadian beef industry, has established five<br />

key guiding principles. Among them is the goal of ensuring that beef<br />

producers adopt practices that sustain and restore ecosystem health.<br />

CRSB’s other principles include respect for people and the community,<br />

animal health and welfare, food quality, efficiency and innovation.<br />

Since 2015, <strong>NCC</strong> has provided technical and financial support to<br />

the CRSB to develop indicators that help ensure that the health of the<br />

grasslands in which ranchers graze livestock is maintained and, wherever<br />

possible, enhanced. <strong>NCC</strong> has also supported the CRSB’s development<br />

of a set of important environmental goals, including the enhancement<br />

of ecological services (such as flood control), improvement of stream<br />

health and reduction of the industry’s water and greenhouse gas<br />

footprints. <strong>NCC</strong> believes that the achievement of these goals is vital<br />

to the conservation of biodiversity.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> understands that our conservation work cannot operate in<br />

isolation, and that effective conservation needs partnerships. Our<br />

partnership with the CRSB will help positively influence biodiversity<br />

and ecosystem health within these working landscapes, on a very<br />

large and ecologically significant scale.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> believes partnerships are essential to effective conservation, and works with<br />

farmers and ranchers to ensure the sustainable management of Canada’s grasslands.<br />

INSET: <strong>NCC</strong>. LANDSCAPE: <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

14 SPRING <strong>2017</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

<strong>NCC</strong> and the Frolek family have worked<br />

together for close to a decade to protect<br />

this grassland habitat near Kamloops, B.C.<br />

2<br />

Conservation-minded ranchers<br />

KAMLOOPS, BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

Each summer, Barb Pryce and Ray Frolek head out into the grasslands near Kamloops,<br />

British Columbia, to check up on <strong>NCC</strong>’s conservation projects there. <strong>NCC</strong> and the Frolek<br />

Cattle Company have been collaborating on grassland conservation since 2008, when the<br />

B.C.<br />

two joined forces to conserve 7,828 acres (3,168 hectares) of this rare and ecologically<br />

significant habitat.<br />

“As a third-generation rancher, Ray sees how the land has changed over time,” says Pryce.<br />

“His understanding of past conditions adds important context to what we are seeing now.”<br />

Ranchers own a lot of private land in B.C.’s rare grassland valleys. Partnering with<br />

conservation-minded ranchers is essential to conserving this important habitat.<br />

“Our relationships with ranchers enable truly amazing conservation in Canada’s grasslands,” says Pryce.<br />

“We couldn’t do this work without them!”<br />

Partner<br />

Spotlight<br />

In 2014, Imperial pledged<br />

$1 million over four years to the<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) in support of the National<br />

Conservation Interns Program.<br />

The work of <strong>NCC</strong>’s conservation<br />

interns is diverse, ranging from<br />

forest and grassland restoration,<br />

to species inventories, trail maintenance<br />

and access. Interns can<br />

also participate in mapping with<br />

geographic information systems,<br />

data management, monitoring<br />

and relationship building with<br />

neighbours, stakeholders and<br />

communities.<br />

FROLEK FAMILY AND <strong>NCC</strong> STAFF: TESSA BUCHAN. CONSERVATION INTERN: <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

3<br />

Home on the range<br />

TWIN BUTTE, ALBERTA<br />

This past summer, <strong>NCC</strong>’s Alberta Region teamed up with a group of rangeland experts to<br />

learn the tricks of the ranching trade. The Rancher’s Rangeland Management Workshop<br />

was held at the Twin Butte Community Hall. The two-day workshop was attended by <strong>NCC</strong><br />

staff, and landowners and ranchers from the surrounding communities.<br />

Presenters included government experts, academics, private consultants and the<br />

landowners themselves. Participants discussed a wide range of topics, including principles<br />

of range management, grazing strategies, weed control and prevention, ecological<br />

services of grasslands and reducing wildlife-livestock conflicts.<br />

4<br />

A new lease on life<br />

WIDEVIEW, SASKATCHEWAN<br />

One of <strong>NCC</strong>’s newest properties in southwest Saskatchewan, Wideview, is now being grazed<br />

by a local rancher’s cattle. <strong>NCC</strong> creates these types of lease agreements on about 90 per cent<br />

of our properties in Saskatchewan, as a way of managing biodiversity while developing good<br />

relationships with our neighbours.<br />

Grazing by domestic cattle simulates the natural processes by which these grasslands<br />

would have historically been influenced by wildfire and herds of bison. This grazing, in<br />

turn, increases biodiversity and fertilizes the soil with manure. <strong>NCC</strong> monitors the grass to<br />

ensure that grazing is maintaining and improving the health of the prairie ecosystem.1<br />

ALTA.<br />

SASK.<br />

“<strong>NCC</strong>’s Conservation Interns<br />

Program provides outstanding<br />

experiences for university and<br />

college students in areas such as<br />

conservation science, land management<br />

and wildlife research,”<br />

says Erica Thompson, <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

senior director for national<br />

conservation engagement<br />

and development.<br />

Imperial is an integrated energy<br />

company committed to developing<br />

our nation’s resources responsibly.<br />

Working with partners like <strong>NCC</strong> to<br />

invest in tomorrow’s conservation<br />

leaders delivers a valuable, longterm<br />

contribution to Canada.<br />

Kim Fox<br />

Vice President of Public and<br />

Government Affairs, Imperial<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 15

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Family values<br />

Richard Ivey’s love for nature and passion for conservation over four decades<br />

have inspired a natural legacy for his family and for countless Canadians<br />

JOEL KIMMEL.<br />

16 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

On December 31, 1947, a family dream became a reality<br />

when Richard Ivey and his father established The Richard<br />

Ivey Foundation. Now known as the Ivey Foundation,<br />

this private, charitable foundation focuses on improving the<br />

well-being of Canadians and supports charitable organizations<br />

in areas such as the environment and climate change.<br />

SUZANNE COOK.<br />

Many people may not realize the importance of that initial collaboration, but today<br />

when you visit protected areas in Ontario, such as on Pelee Island, hike trails in<br />

Algonquin Provincial Park or go birding at Clear Creek Forest, much of these places<br />

are now conserved and available thanks to a family with a passion for nature.<br />

“Our family cottage was just north of Muskoka, along the Magnetawan River<br />

system, in an area surrounded by forest,” recalls Richard Ivey. “We spent several<br />

summers there in my youth. It was an excellent teacher of nature.”<br />

From those summers spent along the banks of the river, Ivey’s appreciation<br />

for nature grew and inspired a lifetime of work dedicated, in part, to protecting<br />

significant Canadian landscapes.<br />

“Throughout the 1970s we turned our attention to environmental grants, first to<br />

the Nature Conservancy of Canada,” wrote Ivey in his 2014 memoir, A Meaningful<br />

Life. “[My wife,] Beryl, was particularly drawn to the environment, and we started<br />

working with the Nature Conservancy [of Canada], helping them acquire and<br />

preserve unique properties in Ontario. One gentleman from the organization,<br />

Mr. Charles Sauriol, took us on tours of beautiful properties that the conservancy<br />

wanted to protect.”<br />

Charles Sauriol was the first director of the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>),<br />

from 1966 to 1987. Sauriol built a fond relationship with the Iveys and grew to know<br />

them well, says John Riley, former <strong>NCC</strong> chief science officer and current board<br />

member of <strong>NCC</strong>’s Ontario Region.<br />

Ivey’s time at the family cottage sparked<br />

an appreciation for nature and inspired<br />

a lifetime of work dedicated, in part, to<br />

protecting significant Canadian landscapes.<br />

“Charles once shared the story of how, in 1970, he took the train from Toronto<br />

to London and walked north to the Ivey home to introduce himself to Richard,”<br />

recalls Riley. “Richard and Beryl’s interest in the spectacular cliffs and waterfalls<br />

along the Niagara Escarpment, one of the conservation causes of the day, was<br />

stimulated as a result.”<br />

Richard Ivey and his family’s contribution through the Ivey Foundation were<br />

essential in helping <strong>NCC</strong> secure and protect vulnerable lands in Ontario’s<br />

Niagara Escarpment region. “With help from the Iveys, <strong>NCC</strong> started buying land<br />

immediately, but soon came up with the idea of a personal visit to John Robarts,<br />

Ontario’s premier at the time, to make a proposition,” says Riley. “Would the<br />

province fund land securement along the Niagara Escarpment on the basis of<br />

a match of $3 of public funding for each $1 of Ivey funding?”<br />

Richard and Beryl on safari in Kenya, 1974<br />

By 1983, more than 5,000 acres (2,020<br />

hectares) were conserved under this agreement,<br />

including in such familiar Ontario<br />

destinations as Spirit Rock, Fishing Islands,<br />

Cave <strong>Spring</strong>s, Silver Creek, Hilton Falls,<br />

Crawford Lake and Inglis Falls.<br />

The Iveys had a particular interest<br />

in protecting these lands, having shared<br />

a long-time connection with the area.<br />

“I could see the falls from the Ridley<br />

College campus, in St. Catharines, where<br />

I went to school,” remembers Ivey. “Shortly<br />

after we got married, my wife began acting<br />

in plays at the Grand Theatre and then<br />

became involved in the Shaw Festival, at<br />

Niagara-on-the-Lake. The area just became<br />

a part of our life together.”<br />

Ivey and his late wife, Beryl, have been<br />

particularly supportive of <strong>NCC</strong>’s work to<br />

conserve lands in southwestern Ontario.<br />

Together with their foundation, the Iveys<br />

have contributed millions of dollars to<br />

support land conservation in areas such as<br />

Pelee Island, Clear Creek Forest, Norfolk<br />

County and countless others.<br />

“This was the first of many great partnerships,<br />

over the years, thanks to which <strong>NCC</strong><br />

has helped realize the conservation dreams<br />

of its supporters,” reflects Riley. “The Ivey<br />

family’s leadership, which Richard Ivey<br />

continues to this day, has inspired conservation<br />

across Canada.”1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2017</strong> 17

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

Lake of Dreams<br />

By Stuart McLean, writer and broadcaster and <strong>NCC</strong> ambassador<br />

The Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) was saddened<br />

to learn of the passing of<br />

Stuart McLean on February<br />

15, <strong>2017</strong>. He was a great<br />

ambassador for <strong>NCC</strong>. In fact,<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> staff were thrilled when<br />

McLean, one of Canada’s<br />

most recognizable voices,<br />

agreed to record the voiceover<br />

for <strong>NCC</strong>’s public service<br />

announcement. He also kindly<br />

agreed to write and present<br />

a story (excerpted here) at<br />

our 50 th anniversary gala.<br />

READ THE FULL STORY<br />

natureconservancy.ca/<br />

stuart-mclean<br />

In the late 1960s Eric and Doris were living in<br />

Edmonton. They were modest people of modest<br />

means. Eric had already retired from his job at<br />

the Co-op. Doris was still working as a teacher.<br />

They were an outdoorsy couple. They had always<br />

enjoyed hiking and skiing and birding. And they were<br />

dreamers. They dreamed of having a place in the country.<br />

But they had never been able to afford one. So in<br />

November of 1971, when they were out for one of their drives,<br />

and they saw a small sign on a country road advertising land<br />

for sale, they stopped and read it. The sign said the wooded<br />

land they were looking at was owned by the Canadian Pacific<br />

Railway and was up for sale by public tender.<br />

Eric and Doris parked their car and walked through<br />

the bush to see what the land looked like. On their hike,<br />

they came across a beautiful and completely undeveloped<br />

lake. It was the lake of their dreams.<br />

Their golden pond.<br />

They went home and, with absolutely no hope of<br />

success, they cobbled together what they could and<br />

submitted a tender.<br />

When the bidding was done, it turned out Eric and<br />

Doris were the only bidders. It turned out they were now<br />

the owners of 320 acres of wooded wilderness: a quarter<br />

section of uncleared land that was home to elk, deer,<br />

moose and waterfowl. And a piece of Coyote Lake.<br />

They erected a little pre-fab house on the edge of the lake.<br />

For three decades, they lived there together. It became<br />

the place the family would gather: for family visits, for<br />

birthdays, to show off babies, to bring new partners or<br />

spouses for Christmas.<br />

The place where young and old would go hiking and<br />

skiing along the trails, canoeing on the lake, skating on<br />

the lake, bird watching beside the lake and star gazing.<br />

In other words, it became the family home.<br />

They thought, “It is so beautiful here. It should always<br />

be like this.”<br />

But there was a problem. Right across from their little<br />

house, there was a point of land that jutted into the lake.<br />

The point was owned by a man who lived in Calgary. Eric<br />

and Doris began to worry about what he might do to that<br />

point one day.<br />

So, Eric and Doris found their way to the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada. They suggested if the conservancy bought<br />

the point, it would mean the lake would be protected forever.<br />

The people from the conservancy explained that they<br />

would love to do that, but it would not mean the lake<br />

would be protected forever. It would mean half the lake<br />

would be protected forever.<br />

Eric and Doris said, “You are right.” And then they said,<br />

“If you will buy the point across the lake, we will give you our<br />

land, and then the whole lake will be protected. Forever.”<br />

It was like saying, “If you buy the point across from us,<br />

we will give you everything we have in the world.”<br />

The conservancy bought the point across the lake. And<br />

Doris and Eric were good to their word.1<br />

ILLUSTRATION: JACQUI OAKLEY. PHOTO: ILIA HORSBURGH.<br />

18 SPRING <strong>2017</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can<br />

define your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada, no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable<br />

habitats and the wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for<br />

generations to come.<br />

Learn more about leaving a gift in your Will at<br />

NatureConservancy.ca/legacy or 1-800-465-0029

YOUR<br />

VOICES<br />

Generations of caring<br />

“My 10-year-old granddaughter, Tanaeya, and I travelled from Ontario<br />

to Saskatchewan to volunteer at Old Man on His Back (OMB). I had the<br />

desire to visit OMB after reading Sharon Butala’s books, and discovering<br />

the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>'s) volunteer program made<br />

all of our travel plans easier. We could not only visit OMB, we could stay<br />

all weekend and they would feed us, too! All for the price of walking<br />

around in the prairie sunshine, putting cans on fence posts, putting<br />

markers on fence wires and meeting other caring Canadians. This<br />

experience showed us that by volunteering, ordinary Canadians can<br />

make a difference to help protect the<br />

land. I wish every child and grandmother<br />

could have the experience of sleeping<br />

under the stars and waking up to<br />

a Saskatchewan sunrise!”<br />

~ Jean Kendall, Brantford, Ontario<br />

Nature for all!<br />

“For me, nature and the prairies are exotic! I am<br />

originally from Vancouver. While there is Stanley Park,<br />

and many other smaller parks for Vancouver residents,<br />

as a child I never got to experience nature very often.<br />

The first time I volunteered for <strong>NCC</strong>, it was on a field trip that involved<br />

the local multicultural society, allowing new Canadians to see the natural<br />

prairie landscape that was now their new home. I support the conservancy<br />

with my donations and time because it preserves what remains<br />

of the wilderness and teaches all of us to appreciate the grasses, trees, air,<br />

gophers, deer, moose and insects — even mosquitoes — that live with us!<br />

We need to appreciate what we have, and the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada teaches us how.”<br />

~ Gail Chin, Regina, Saskatchewan<br />

Front lines of conservation<br />

“As an <strong>NCC</strong> volunteer and land donor in west<br />

Quebec, I appreciate the intrinsic value of<br />

protected spaces. My wife, Charlotte, and I have<br />

donated to <strong>NCC</strong> approximately 300 acres (120<br />

hectares) of property in the Ottawa River watershed.<br />

It’s not a huge property, but it can now<br />

continue to mature as a protected natural<br />

forest and productive wetlands. Perhaps, when<br />

combined with other properties, it will contribute<br />

to an important wildlife corridor.<br />

“I also volunteer at other <strong>NCC</strong> properties along the<br />

Ottawa River — in Breckenridge, Clarendon and<br />

Bristol, Quebec. I greatly enjoy the opportunities<br />

to learn from other volunteers as well as fisheries<br />

biologists and ornithologists as they survey<br />

properties to guide conservation efforts.<br />

“I spent the final years of my career [as an assistant<br />

deputy minister for Environment Canada]<br />

working on environmental policies and regulations.<br />

Now, to be on the front lines, working on<br />

the properties, gives me great satisfaction.”<br />

~ Barry Stemshorn, Gatineau, Quebec<br />

MARK TAYLOR. GAIL CHIN. <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

Send us your stories! magazine@natureconservancy.ca<br />

NATURE CONSERVANCY OF CANADA<br />

36 Eglinton Avenue West, Suite 400, Toronto, Ontario M4R 1A1