Caribbean Beat — January/February 2017 (#143)

A calendar of events; music, film, and book reviews; travel features; people profiles, and much more.

A calendar of events; music, film, and book reviews; travel features; people profiles, and much more.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

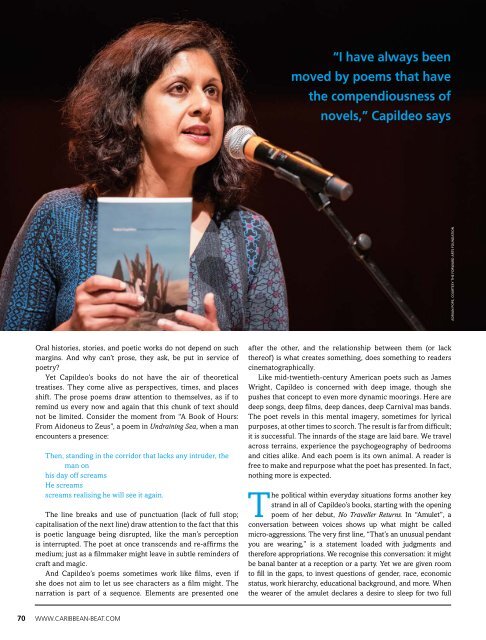

“I have always been<br />

moved by poems that have<br />

the compendiousness of<br />

novels,” Capildeo says<br />

Adrian Pope, courtesy the Forward Arts Foundation<br />

Oral histories, stories, and poetic works do not depend on such<br />

margins. And why can’t prose, they ask, be put in service of<br />

poetry?<br />

Yet Capildeo’s books do not have the air of theoretical<br />

treatises. They come alive as perspectives, times, and places<br />

shift. The prose poems draw attention to themselves, as if to<br />

remind us every now and again that this chunk of text should<br />

not be limited. Consider the moment from “A Book of Hours:<br />

From Aidoneus to Zeus”, a poem in Undraining Sea, when a man<br />

encounters a presence:<br />

Then, standing in the corridor that lacks any intruder, the<br />

man on<br />

his day off screams<br />

He screams<br />

screams realising he will see it again.<br />

The line breaks and use of punctuation (lack of full stop;<br />

capitalisation of the next line) draw attention to the fact that this<br />

is poetic language being disrupted, like the man’s perception<br />

is interrupted. The poet at once transcends and re-affirms the<br />

medium; just as a filmmaker might leave in subtle reminders of<br />

craft and magic.<br />

And Capildeo’s poems sometimes work like films, even if<br />

she does not aim to let us see characters as a film might. The<br />

narration is part of a sequence. Elements are presented one<br />

after the other, and the relationship between them (or lack<br />

thereof) is what creates something, does something to readers<br />

cinematographically.<br />

Like mid-twentieth-century American poets such as James<br />

Wright, Capildeo is concerned with deep image, though she<br />

pushes that concept to even more dynamic moorings. Here are<br />

deep songs, deep films, deep dances, deep Carnival mas bands.<br />

The poet revels in this mental imagery, sometimes for lyrical<br />

purposes, at other times to scorch. The result is far from difficult;<br />

it is successful. The innards of the stage are laid bare. We travel<br />

across terrains, experience the psychogeography of bedrooms<br />

and cities alike. And each poem is its own animal. A reader is<br />

free to make and repurpose what the poet has presented. In fact,<br />

nothing more is expected.<br />

The political within everyday situations forms another key<br />

strand in all of Capildeo’s books, starting with the opening<br />

poem of her debut, No Traveller Returns. In “Amulet”, a<br />

conversation between voices shows up what might be called<br />

micro-aggressions. The very first line, “That’s an unusual pendant<br />

you are wearing,” is a statement loaded with judgments and<br />

therefore appropriations. We recognise this conversation: it might<br />

be banal banter at a reception or a party. Yet we are given room<br />

to fill in the gaps, to invest questions of gender, race, economic<br />

status, work hierarchy, educational background, and more. When<br />

the wearer of the amulet declares a desire to sleep for two full<br />

70 WWW.CARIBBEAN-BEAT.COM