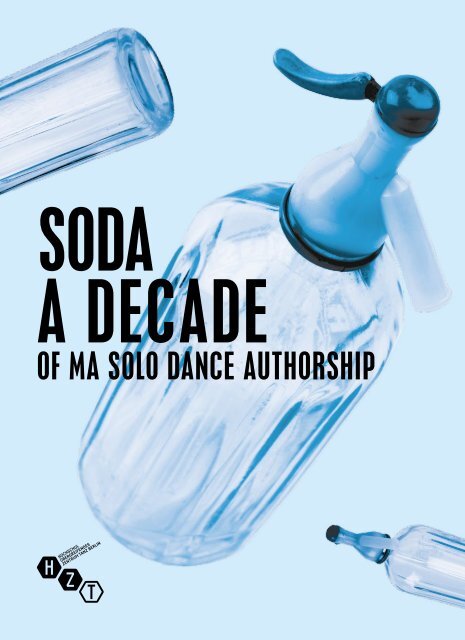

A Decade of MA Solo Dance Authorship

In the frame of the 10th anniversary of MA SODA in 2017, the independent writer, editor and consultant and former guest professor Richard Allsopp edited the publication “SODA – A DECADE OF MA SOLO DANCE AUTHORSHIP”. “The aim of this book on a decade of SODA at the HZT Berlin is to provide a retrospective insight into the imaginative, discursive and educational spaces that the SODA programme has opened-up since its beginning in 2007. [...]" Ric Allsopp, November 2017

In the frame of the 10th anniversary of MA SODA in 2017, the independent writer, editor and consultant and former guest professor Richard Allsopp edited the publication “SODA – A DECADE OF MA SOLO DANCE AUTHORSHIP”.

“The aim of this book on a decade of SODA at the HZT Berlin is to provide a retrospective insight into the imaginative, discursive and educational spaces that the SODA programme has opened-up since its beginning in 2007. [...]" Ric Allsopp, November 2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SODA<br />

A DECADE<br />

OF <strong>MA</strong> SOLO DANCE AUTHORSHIP

2

SODA<br />

A DECADE<br />

OF <strong>MA</strong> SOLO DANCE AUTHORSHIP<br />

Inter-University Centre for <strong>Dance</strong> Berlin (HZT)<br />

3

After all, what is history if it is not an imagined past –<br />

a collection <strong>of</strong> facts, which are viewed and interpreted in the light<br />

<strong>of</strong> our own experiences?<br />

Shirley Baker – Photographer, 1932–2014<br />

The making <strong>of</strong> art is highly individual, possibly spontaneous and<br />

to some extent always intuitive – sometimes even contradictory.<br />

Is it possible to define the conditions in which the various art forms<br />

can optimally develop? And if so, can we translate them into a<br />

structured pedagogical system?<br />

Georg Weinand – SODA Symposium, 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

1<br />

5<br />

21<br />

35<br />

55<br />

Preface<br />

Introduction<br />

Beginnings (2005-2006)<br />

Development (2006-2007)<br />

SODA Draft Curriculum (2006)<br />

Ethos & Poetics<br />

Locations<br />

Programme<br />

Student Handbook Extracts (2010-2017)<br />

Core Approaches<br />

Course Structure<br />

Workbooks & Framing Statements<br />

Extracts I<br />

Introduction<br />

Céline Cartillier (2012–2014)<br />

Felix Marchand (2007–2009)<br />

Flavio Ribeiro (2012–2014)<br />

Kat Válastur (2007–2009)<br />

Jee-Ae Lim (2011–2013)<br />

Maria Baroncea (2012–2014)<br />

Mirko Winkel (2007–2009)<br />

SODA Pilot Group Workbooks (2007–2009)<br />

Networks<br />

SODA Postgraduate Platform (2009)<br />

Erasmus Intensive Project (2011–2013)<br />

Erasmus IP Report (2012) – Litó Walkey<br />

Capturing <strong>Dance</strong>: Berlin - Cologne (2015–2016)<br />

Exchange Project: Berlin - Stockholm -<br />

Montpellier (2015)

73<br />

89<br />

95<br />

129<br />

134<br />

137<br />

138<br />

Extracts II<br />

Sophia New – ‘Refreshing Experience’<br />

Boyan Manchev – ‘Educational Micropolitics’<br />

Litó Walkey – ‘Performance Directives’<br />

Ric Allsopp – ‘Spaces <strong>of</strong> Appearance’<br />

Sophia New – ‘Expanding Notions Through Experience’<br />

Interview<br />

Interview with Rhys Martin (July 2017)<br />

Extracts III<br />

Ana Monteiro (2010–2012)<br />

Andrew Wass (2011–2013)<br />

Willy Prager (2011–2013)<br />

Daniel Kok (2010–2012)<br />

Enrico D. Wey (2015–2017)<br />

Yaron Maïm & Group<strong>Solo</strong> (2016–2018)<br />

Katrin Memmer (2012–2014)<br />

Ixchel Mendoza Hernandez (2013–2015)<br />

Elisabete Finger (2010–2012)<br />

Helena Botto (2013–2015)<br />

Kyla Avery Kegler (2013–2015)<br />

Mădălina Dan (2014–2016)<br />

Sheena McGrandles (2010–2012)<br />

Liad Hussein Kantorowicz (2015–2017)<br />

Addenda<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA Students (2007–2017)<br />

Exchange & Guest Students (2010–2016)<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA Staff (2007–2017)<br />

HZT Direction & Administration (2006–2017)<br />

SODA WORKS (2009–2017)<br />

Visiting Guests & Mentors (2007–2017)<br />

External Examiners (2009–2017)<br />

Erasmus Intensive Project Staff (2011–2013)<br />

SODA Staff Biographies<br />

References<br />

Colophon

PREFACE<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> this book on a decade <strong>of</strong> SODA at the HZT Berlin is to<br />

provide a retrospective insight into the imaginative, discursive<br />

and educational spaces that the SODA programme has opened-up<br />

since its beginnings in 2007. The book is not intended to be a definitive<br />

history or a celebration <strong>of</strong> special achievements (<strong>of</strong> which<br />

there have been many on both individual and institutional levels)<br />

but as more <strong>of</strong> a glimpse, an aide memoire for those involved, a<br />

partial insight for those at a distance. It <strong>of</strong>fers a set <strong>of</strong> links and<br />

connections to current and past work by students, staff and alumni;<br />

a graphic play <strong>of</strong> extracts, texts and images, a vade mecum for<br />

the curious or perplexed that tracks some <strong>of</strong> the choreographic,<br />

poetic and performative spaces that SODA has explored. As the<br />

second SODA group (2010–2012) outlined in ‘Anything but <strong>Solo</strong>’,<br />

the introduction to their final SODA Works programme:<br />

One <strong>of</strong> our first SODA lectures dealt with dance as an<br />

open concept. Reading Eco and Barthes as a group not<br />

only quickly led us to question our preconceived notions<br />

regarding authorship, but also established a common language<br />

for us to communicate with in the months to come.<br />

What is ‘open’? Open to what? And for whom? These<br />

were precisely the kinds <strong>of</strong> questions that we would busy<br />

ourselves with in practical workshops as well a table<br />

discussions.<br />

One gift that a programme like SODA <strong>of</strong>fers is time – the<br />

time to sharpen and redefine our artistic methodologies,<br />

the time to ponder over feedback about our work, and<br />

perhaps more importantly, the time to reflect critically on<br />

the very conditions <strong>of</strong> performance creation and production.<br />

By challenging ourselves to reconsider the contextual<br />

frameworks that surround art making, we have sought<br />

to leave little taken for granted while asserting our independent<br />

practices as critical research. [...]<br />

(SODA Works 2011: 3)<br />

Uferstudios Backgrounds (2011) Photo © Sven Hagolani<br />

1

This is an appropriate place to thank all those who have contributed<br />

in a multitude <strong>of</strong> ways to making the SODA programme the<br />

dynamic, contested, and at times infuriating or ecstatic focus for<br />

postgraduate dance and body-based performance education<br />

over the last decade; and an opportunity to thank all those who<br />

have contributed to the making <strong>of</strong> this book in the hope that it<br />

might provide a further stepping stone for the future directions <strong>of</strong><br />

SODA; especially Yaron Maïm and all the current (2016–2019)<br />

SODA students for their collaborative ‘groupsolo’ contribution<br />

and energies which carry SODA forward; Eva-Maria Hoerster,<br />

Sabine Trautwein and the indomitable Rhys Martin, without whom<br />

SODA would have remained but a sweet fizzy confection in a bottle;<br />

and Pierre Becker at Ta-Trung for his generous collaborative<br />

design work on this book.<br />

Ric Allsopp, November 2017<br />

A supplementary digital version <strong>of</strong> SODA: A <strong>Decade</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Solo</strong> <strong>Dance</strong> <strong>Authorship</strong> is published on ISSUU –<br />

www.issuu.com/hztberlin – and contains hyper-links to all aspects <strong>of</strong> the SODA programme and its histories<br />

currently available online – www.hzt-berlin.de<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA Events 2010–2017 – www.hzt-berlin.de/SODA-events – is an online digital file that contains all<br />

SODA related materials that have been posted to the HZT website from 2010 to the present - and includes<br />

descriptions and information <strong>of</strong> the SODA Lectures Series / Workshops / SODA Works / 301 Research<br />

presentations and other events.<br />

2

HZT 10 th Anniversary Party (April 2017) Photo © Marion Borriss<br />

3

INTRODUCTION<br />

Initiated as one <strong>of</strong> two postgraduate programmes <strong>of</strong> the Inter-<br />

University Centre for <strong>Dance</strong>, Berlin (HZT) <strong>MA</strong> SODA was developed<br />

alongside <strong>MA</strong> Choreography as a generative artistic and educational<br />

framework under the auspices <strong>of</strong> the University <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Arts (UdK) and the Ernst Busch Academy <strong>of</strong> Dramatic Arts (HfS),<br />

Berlin. 1<br />

SODA: A <strong>Decade</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>MA</strong> <strong>Solo</strong> <strong>Dance</strong> <strong>Authorship</strong> traces the work <strong>of</strong><br />

the SODA programme over its first 10 years and marks its contribution<br />

to the rethinking and expansion <strong>of</strong> dance and performance<br />

discourses, practices and educational frameworks that continue<br />

to reshape contemporary cultural and artistic environments. The<br />

book, and its partner publication drawing from what falls next to<br />

you (HZT, 2017) provides an insight into the diverse directions that<br />

the work <strong>of</strong> SODA’s past and present students have taken, the international<br />

networks that the programme has contributed to, and<br />

the educational framework and approach that the artists, theorists<br />

and academics involved with the programme have developed<br />

with the students.<br />

The SODA programme has enabled its students and staff, as<br />

artists, thinkers and makers, to explore the unstable and contested<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> ‘solo’, ‘dance’ and ‘authorship’, which provided the<br />

acronym SODA, within the framework <strong>of</strong> a two-year postgraduate<br />

focus on the individual, collaborative and body-based processes<br />

<strong>of</strong> dance and performance making. SODA draws on performative,<br />

philosophical and theoretical strategies informed by choreographic,<br />

somatic, performance and fine arts practices, to situate<br />

its educational and artistic practice in relation to the field <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

performance and culture.<br />

Uferstudios Backgrounds (2011) Photo © Sven Hagolani<br />

5

BEGINNINGS (2005–2006)<br />

The SODA programme emerged as a key feature <strong>of</strong> the HZT project<br />

and in relation to an educational design zeitgeist that was perhaps<br />

characteristic <strong>of</strong> the early years <strong>of</strong> the new century. It built<br />

on the links and experiences <strong>of</strong> other European programmes and<br />

initiatives that were concerned with experimental educational<br />

models for dance and performance arts including the School for<br />

New <strong>Dance</strong> Development (SNDO) and DAS Arts in Amsterdam,<br />

ArtEZ in Arnhem, and Dartington College <strong>of</strong> Arts in England.<br />

It set out to develop a transdisciplinary programme in ‘solo, dance /<br />

choreographic authorship’ as can be seen in the initial proposal<br />

outlined in November 2005 by Rhys Martin, then Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Dance</strong> and Choreography within the Musical / Show programme<br />

at the UdK, and in response to Tanzplan Deutschland, an initiative<br />

<strong>of</strong> the German Federal Cultural Foundation which provided<br />

infra-structural funding (2005–2010) to improve the basic conditions<br />

for dance across Germany and to strengthen it as an art form<br />

in public and cultural policy perception.<br />

The Berlin application for funding from Tanzplan Deutschland<br />

brought together the UdK and the HfS with TanzRaum, a network <strong>of</strong><br />

the Berlin pr<strong>of</strong>essional dance scene, in a single project to integrate<br />

higher education in dance in Berlin with the independent dance<br />

sector under a ‘co-operative centre for dance’ which became the<br />

HZT (Inter-University Centre for <strong>Dance</strong>, Berlin) in April 2006.<br />

The initial SODA proposal suggested a ‘post-graduate two year,<br />

full-time transdisciplinary <strong>MA</strong> degree in solo, dance / choreographic<br />

authorship, at the Department <strong>of</strong> Performing Arts UdK,<br />

Berlin; to be initially installed as a pilot project beginning Autumn<br />

2006.’ (Martin, 2005)<br />

6

Its aims were to:<br />

• pursue intellectual agility <strong>of</strong> purpose, process, artistic excellence<br />

and maturity <strong>of</strong> performance<br />

• establish a new state <strong>of</strong> the art, unique performative oriented<br />

postgraduate degree designed to situate solo dance performance<br />

into the transdisciplinary artistic contexts <strong>of</strong> the twentyfirst<br />

century<br />

• draw on the pre-war legacy <strong>of</strong> Germany as a leading innovator in<br />

contemporary dance and Berlin’s unique role as a pioneer <strong>of</strong> solo<br />

dance performance<br />

•reposition Berlin as a dynamic international protagonist in this<br />

rapidly developing innovative contemporary art form<br />

• foster the self-driven development <strong>of</strong> qualified candidates and<br />

independent authors <strong>of</strong> contemporary solo dance performance<br />

and to equip them with postgraduate research techniques and<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> diverse artistic processes<br />

• position those authors firmly at the centre <strong>of</strong> current trends <strong>of</strong><br />

artistic practice by exposure to a wide range <strong>of</strong> established contemporary<br />

artists, innovative thinkers and practitioners <strong>of</strong> performance<br />

related disciplines<br />

• provide an understanding <strong>of</strong> the major contours <strong>of</strong> international<br />

research and develop their capacity for critical evaluation <strong>of</strong><br />

relevant scholarly literature<br />

• provide structural positioning for project-based higher degrees<br />

(PhD, Research Fellowships) and to develop creative partnerships<br />

with European and international educational institutions<br />

and pr<strong>of</strong>essional practitioners. (Martin, 2005)<br />

7

Uferstudios and the Panke from Badstrasse (2010) Photo © he.he<br />

In the initial research phase (2005–2006) and in advance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

SODA pilot project, Rhys Martin initiated several conversations<br />

with choreographers and academics that give a sense <strong>of</strong> prevalent<br />

educational concerns and provided some guidelines for the<br />

conceptualisation <strong>of</strong> the programme. William Forsythe argued that<br />

‘the learning process <strong>of</strong> a dance education is central, so the<br />

question ‘how do we know something’ must be the focus’. Xavier<br />

Le Roy also noted that ‘the most important question is not the<br />

content <strong>of</strong> the lessons, but the form. The ‘how’ must stand clearly<br />

before the ‘what’. He went on to ask whether art can be taught at<br />

all: ‘an ideal education institute creates more a situation in which<br />

questions about art can be asked.’ Johannes Odenthal considered<br />

that any future-oriented dance education ‘must be able to<br />

liberate itself from the aesthetic restrictions <strong>of</strong> style determination’.<br />

(SODA Archives, 2005–06)<br />

A SODA Working Group 2 was set up to convene a Symposium on<br />

<strong>Solo</strong> <strong>Dance</strong> <strong>Authorship</strong> (25–27 August 2006). The three-day<br />

Symposium was designed as a forum for solo dance performers /<br />

choreographers, artists and theoreticians, representatives <strong>of</strong><br />

postgraduate courses in the field <strong>of</strong> contemporary dance / choreography<br />

and partners from other disciplines who were interested<br />

in solo dance authorship. The Symposium was hosted by Rhys<br />

Martin in collaboration with the International Festival Tanz im<br />

August and included <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the key figures in contemporary<br />

dance, choreography, performance and education in Europe who<br />

8

were invited on the strength <strong>of</strong> ‘their involvement with solo performance,<br />

authorship questions or experience in postgraduate<br />

study programmes.’ 3<br />

The Symposium also exposed some <strong>of</strong> the fundamental ideas,<br />

issues and areas <strong>of</strong> contention implicit in an educational programme<br />

exploring ‘solo, dance, authorship’, ideas which would<br />

directly and indirectly inform the direction <strong>of</strong> the programme and<br />

form a substrate and a catalyst for its development, establishing<br />

at least a problematic ground from which SODA could operate. The<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> a ‘problematic’ as a basis for a postgraduate programme<br />

drew on an educational idea <strong>of</strong> a common research project (equally<br />

involving both staff and students) that addresses the terms <strong>of</strong><br />

its title – in this case solo, dance and authorship.<br />

In September 2006 Franz-Anton Cramer drew up a summary report<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Symposium based on notes and transcripts which amongst<br />

other observations and remarks, noted a ‘growing discomfort with<br />

the idea <strong>of</strong> working on solo dance authorship.’ (Cramer, 2006:25)<br />

Regardless <strong>of</strong> the difficulties in defining what solo as a performance<br />

format would be, whether it is relevant to contemporary<br />

practice or transports too much <strong>of</strong> pre-contemporary concerns<br />

and working methods; regardless also <strong>of</strong> the question whether<br />

education should focus on solo or rather on artistic development<br />

in a more general, and less determining sense, the following categories<br />

<strong>of</strong> solo work were formulated:<br />

• Being a soloist in a group<br />

• <strong>Solo</strong> as part <strong>of</strong> a process<br />

• <strong>Solo</strong> as a way <strong>of</strong> studying<br />

• <strong>Solo</strong> making for others<br />

• <strong>Solo</strong> for the self<br />

• <strong>Solo</strong> as self-exploration. (Cramer, 2006:24–25)<br />

9

The Symposium also exposed the more general tensions and disagreements<br />

that continue to exist in approaches to practice-led<br />

education and artistic research particularly at postgraduate level:<br />

whether art can be taught or not, and the relationships between<br />

teaching and learning, perhaps exemplified in Rosemary Butcher’s<br />

remarks which insisted that<br />

... there should be no vision. Education should rather be understood<br />

as a process, like a journey. It should be about submerging<br />

oneself into what one wants to learn; not about the multiplicity <strong>of</strong><br />

possibilities but about insisting on your own process. If education<br />

generally relies on the past and that which is known in order to<br />

enable and direct that which is to come, it nevertheless seems<br />

necessary to insist on ‘not doing what history made, but knowing<br />

what history gave. (Rosemary Butcher in Cramer, 2006: 24)<br />

If the programme title - solo, dance, authorship - and the issues<br />

around the categories and potentials <strong>of</strong> solo work left the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> the programme unresolved, the Symposium had at<br />

least provided the ground work for a programme whose title could<br />

form the basis for exploration. As Franz-Anton Cramer noted ‘the<br />

notion <strong>of</strong> solo as an historic fact being beyond doubt, its transferability<br />

to contemporary concerns need[ed] more clarification’.<br />

(Cramer, 2006:25) The dramaturg Myriam van Imshoot summarised<br />

the symposium ‘impasse’ as follows: ‘If we cannot talk about the<br />

essential scope and content <strong>of</strong> the education project, how can we<br />

try to talk about the structural surroundings?’ Such a discussion<br />

was to be the next phase <strong>of</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> SODA. Responding<br />

to the Symposium summary, Rhys Martin commented:<br />

Is there a divide here between academia and practice? In view <strong>of</strong><br />

these conflicting reactions to the general proposal it will be advisable<br />

and necessary to look at the whole idea again in greater<br />

detail. Certainly, there is a potential in the title to create a negative<br />

perception <strong>of</strong> the programme. Does this lie in the name itself or<br />

the substance <strong>of</strong> the course structure espoused, or with the central<br />

idea itself? Without doubt, there is a need to examine this in<br />

detail and redraft [the SODA proposal] where necessary. The<br />

Symposium was designed to draw out these possible areas <strong>of</strong><br />

difference and disagreement as well as suggestions for innovation<br />

and development. While I believe that upon further analysis,<br />

the fundamental thrust <strong>of</strong> the programme reflects many <strong>of</strong> the<br />

artistic concerns and practices present at the Symposium, there<br />

is nevertheless a strong case to reappraise the current proposal<br />

to incorporate those concerns addressed. (Cramer, 2006: 29)<br />

10

Uferhallen from the back <strong>of</strong> the Alte Kantine (2010) Photo © Ric Allsopp<br />

DEVELOPMENT (2006–2007)<br />

Following the Symposium two further steps <strong>of</strong> the SODA research<br />

phase took place in 2006 and early 2007. In November 2006, an<br />

experimental laboratory was conducted to test and evaluate the<br />

learning structures for the proposed Artistic Reference Frame<br />

(ARF) Choreographer Plus - a module envisioned for the SODA<br />

pilot programme which ‘concentrat[ed] on the individual processes<br />

<strong>of</strong> the artist / choreographer and the development <strong>of</strong> their<br />

authorial concerns in a transdisciplinary context’. The first ARF<br />

was a one-week research laboratory for which a leading choreographer<br />

(Deborah Hay, USA) was invited to choose two peer artists<br />

or partners (Margaret Cameron, AUS; and Rosa Casado, ES) to<br />

form an artistic reference frame. This <strong>of</strong>fered highly experienced,<br />

artistic resources to eight SODA ‘test candidates’ (through an<br />

open call for participation) to enhance, focus and facilitate their<br />

research skills and artistic practice. A second ARF Choreographer<br />

Plus laboratory was convened in January 2007 and lead by Ibrahim<br />

Quarishi (USA/F) with Gabriel Smeets (NL).<br />

11

Uferstudios Chimney (2011) Photo © he.he<br />

A revised SODA Working Group was extended to concentrate on<br />

the SODA programme and curriculum development, and included<br />

consultancy from Susan Melrose (Middlesex University), Pirkko<br />

Huseman (HAU), Heike Roms (Aberystwyth University) and others.<br />

At the same time an International Advisory Board (IAB) (2006–<br />

2010) was convened to advise on the general development <strong>of</strong> the<br />

HZT project as well as on the development <strong>of</strong> its educational<br />

programmes and their curricula. 4 A Fachkommission (Expert Committee)<br />

had been set up by the Berlin Senate right at the beginning<br />

<strong>of</strong> the HZT pilot phase. Its function was to advise on the<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> the HZT and on the development <strong>of</strong> the HZT curricula<br />

on a regular basis, meeting at least once a month, sometimes<br />

more <strong>of</strong>ten; whereas the function <strong>of</strong> the IAB was to provide an<br />

outside, overview perspective. The members <strong>of</strong> the Fachkommission<br />

also represented the institutions involved. 5<br />

In its initial phase the HZT project was given the go-ahead to<br />

research and develop two new study programmes commencing in<br />

April 2007: the BA in Contemporary <strong>Dance</strong> & Choreography and in<br />

October 2007, the <strong>MA</strong> SODA which (subject to accreditation) were<br />

then incorporated into the HZT from 2010 alongside the <strong>MA</strong> in<br />

Choreography (<strong>MA</strong>C) which developed from the existing HfS Ernst<br />

Busch Diploma programme, and started in October 2008. The<br />

SODA programme that emerged between 2006 and 2010 can be<br />

seen as a slow process <strong>of</strong> working through the paradoxes and<br />

entanglements that emerged from the first Symposium.<br />

12

SODA DRAFT CURRICULUM (2006)<br />

An essential element <strong>of</strong> the curriculum proposal is the perceived<br />

need to install a dynamic educational platform that will allow<br />

students to access contemporary practice as it is found in the<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ession. It is intended to do this through the high frequency <strong>of</strong><br />

guest teachers and mentors constantly replenished subject to<br />

availability and suitability for the candidates currently in the programme.<br />

Maximum flexibility is required to <strong>of</strong>fer the broadest<br />

range <strong>of</strong> artistic leadership. However, continuity will be provided<br />

through ongoing mentor supervision. (Martin, 2006)<br />

Semester 1: Embodied Thought - Block 1 (6 weeks)<br />

A high impact concentration <strong>of</strong> diverse theoretical and practical<br />

knowledge will be identified and coordinated in a varied programme<br />

<strong>of</strong> lectures, seminars, tutorials, discussions and classes.<br />

The body and its readings provide a metaphorical structure to<br />

stimulate discovery <strong>of</strong> new knowledge bases and un-researched<br />

themes. They are not courses in the traditional sense, but more<br />

akin to a reference library through which the students acquire<br />

useful tools and directions for their own work - new starting points<br />

and impulses.<br />

For example: External Embodiment: motion capture, life model<br />

drawing, choreography techniques, martial arts; Visual / Eyes:<br />

graphic 2D-3D, digital technology, prototyping; Acoustic / Ear: sound<br />

studies composition; Tactile / Hand: dramaturgy, sign-language,<br />

hermeneutics, critical writing and documentation; Cognitive / Brain:<br />

theory <strong>of</strong> aesthetics performance, sociology, psychology, contextualization;<br />

Internal Embodiment: anatomy, body- mind-centering,<br />

Pilates, yoga, meditation.<br />

Lectures are planned in cooperation with various departments <strong>of</strong><br />

the UdK and other Berlin universities, and with invited specialists.<br />

During the Embodied Thought block a daily movement class will<br />

be <strong>of</strong>fered by guest teachers.<br />

13

Semester 1: Laboratory Series 1 (Fremdgehen [externalize]) –<br />

Block 2 (8 weeks)<br />

An intensive work-phase consisting <strong>of</strong> 8 x 1 week-long laboratories<br />

with leading non-dance artists. In order to allow creative<br />

space to develop an individual choreographic voice, it is proposed<br />

that students first attempt to understand and participate in the<br />

aesthetics and methods <strong>of</strong> practice <strong>of</strong> artists <strong>of</strong> other disciplines.<br />

These think-tanks / workshops aim to generate a wide experience<br />

base <strong>of</strong> creative thought processes and applications. The content<br />

<strong>of</strong> the laboratory is determined by the leader in negotiation with<br />

students. It’s fundamental premise is that knowledge is embedded<br />

in the practitioner and is not separated into subject and teacher.<br />

Semester 2: Laboratory Series 2 - Choreographer Plus (8 weeks)<br />

A second intensive work-phase <strong>of</strong> 8 x 1 week-long laboratories<br />

with leading choreographers. After students have had the opportunity<br />

to familiarize with other approaches and research fields,<br />

they will be encouraged to develop their own access to research<br />

and develop their skills to critically discuss and if necessary<br />

defend their own ideas and viewpoints with established pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

artists and mentors. The choreographers will lead the laboratory<br />

with two other peer artists / creative collaborators. Creative<br />

teams will be built with other students from appropriate courses<br />

from affiliated programmes.<br />

Semester 3: Independent Trajectory<br />

Students will be required to articulate and formulate a chosen<br />

path <strong>of</strong> artistic enquiry. The aim <strong>of</strong> the semester is to identify and<br />

consolidate a personal research question that will lead to a final<br />

project in Semester 4. Students may attend the laboratories <strong>of</strong><br />

Semester 2. However, a mentoring system will be developed that<br />

will best serve the needs <strong>of</strong> the now independent researcher.<br />

Semester 4: Final Project<br />

The final project is the equivalent <strong>of</strong> a written thesis in conventional<br />

postgraduate programmes. It can take the form <strong>of</strong> a full-length<br />

performance or equivalent – for example an installation, film,<br />

multi-media project etc. Following the first academic year and its<br />

intensive study programme, the second academic year is targeted<br />

at individual research and realization <strong>of</strong> individual projects.<br />

14

Alte Kantine Garden (2011) Photo © Ric Allsopp

Mime Centrum Entrance<br />

(2008)<br />

Photo © Ric Allsopp<br />

The curriculum that was formulated for the pilot phase <strong>of</strong> SODA in<br />

2006 perhaps predictably underwent some considerable rethinking<br />

and remodelling in response to the realities, reactions and<br />

critical feedback from the pilot SODA group between 2007–2009.<br />

Ric Allsopp - a member <strong>of</strong> the International Advisory Board - was<br />

co-opted to join Rhys Martin in the delivery <strong>of</strong> the pilot phase from<br />

October 2007 and, between July 2009 and March 2010, to work on<br />

the further development <strong>of</strong> a programme handbook and curriculum<br />

for the first ‘incorporated’ <strong>MA</strong> SODA student intake (2010–<br />

2012) in April 2010. The ‘scope and content <strong>of</strong> the education project’<br />

that was to be developed over this period established the<br />

terms ‘solo dance authorship’ as a generative problematic to be<br />

understood, experienced and transformed at the level <strong>of</strong> the individual<br />

within a flexible institutional framework. The ‘structural<br />

surroundings’ <strong>of</strong> the HZT as Franz-Anton Cramer put it, the proximity<br />

<strong>of</strong>, and interaction with the independent dance scene, students<br />

and staff from other academic disciplines, faculties and institutions<br />

and the wider cultural, artistic and social resources and<br />

opportunities <strong>of</strong> Berlin also began to seed collaborative crosspollination<br />

- for example in the SODA WORK flyer (July 2009), and<br />

the student organised network / artist / student meetings and<br />

performances (see Networks). The international artistic and educational<br />

networks that both staff and students could draw on underpinned<br />

the gradual shift from the initial ideas <strong>of</strong> ‘solo dance<br />

authorship’ to ‘body-based practices’. The aims set out in the<br />

2006 draft stated that:<br />

The course shall be learner driven. The program has as its focus<br />

the enabling <strong>of</strong> a highly skilled autonomous contemporary dance<br />

performance / choreographer as both researcher and artist. It will<br />

provide opportunities to extend knowledge, competence and understanding<br />

in the theory and practice <strong>of</strong> dance as an art. It recognises<br />

the creative and intellectual freedom <strong>of</strong> talented individuals<br />

to seek out, develop and determine those areas <strong>of</strong> knowledge that<br />

will best serve their own field <strong>of</strong> enquiry and which facilitate their<br />

artistic development. It recognises the primary importance <strong>of</strong><br />

establishing and encouraging a unique artistic sensibility and<br />

voice in new practitioners. (Cramer, 2006: 22)<br />

16

In the most recent (July 2017) SODA Admissions vimeo 6 Rhys Martin<br />

and Sophia New affirm that the SODA programme is looking for<br />

postgraduates ‘who are interested in being challenged, who want<br />

to work within a community <strong>of</strong> artists, people who have a strong<br />

sense <strong>of</strong> performance identity, who are fluent in English and international<br />

in attitude’ and in terms <strong>of</strong> dance, for people ‘who have a<br />

body-based practice - and we understand dance in a very expanded<br />

sense’. The aims and curriculum in the current (2017–19) SODA<br />

Handbook [see Programme] remain close in form and content to<br />

the initial 2010–2012 version.<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA aims to provide a distinctive, practice-led postgraduate<br />

level education for practitioners and graduates who wish to make<br />

dance and body-based performance work in relation to embodied<br />

and conceptual practice, and engage with and reflect on the physical,<br />

compositional, intellectual and cultural processes involved.<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA is aimed at dancers, performers, artists and makers who<br />

have already established a motivated (but not necessarily pr<strong>of</strong>essional)<br />

practice in dance and performance, who wish to extend<br />

and develop the forms, contexts and intellectual range <strong>of</strong> their<br />

work, and who wish to engage with the contexts, challenges and<br />

environments <strong>of</strong> contemporary practice.<br />

17

ETHOS AND POETICS<br />

If SODA has established itself over the last decade not so much as<br />

a singular vision but as a flexible structure, then like any postgraduate<br />

programme that builds a certain reputation for experimentation<br />

and risk-taking within the constraints <strong>of</strong> an institution, it has<br />

also established an ethos over time. Perhaps it is a ‘choreographic<br />

unconscious’ 7 that we inherit from the collaborative, collective<br />

and individual experiences that have formed and shaped the diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the SODA histories so far, but perhaps it is also an ethos<br />

which, as Nicolas Ridout puts it, is concerned with the realisation<br />

<strong>of</strong> individual and social potential, <strong>of</strong> an orientation towards the<br />

‘other’; as a concern with process and form rather than content,<br />

characterised by ‘an openness to the future and the unpredictable<br />

rather than a closure around a specific ethical position’ and<br />

the ‘production <strong>of</strong> ethical relations and situations’ rather than a<br />

concern with aesthetics. (Ridout, 2009: 49). It might also, from a programme<br />

point <strong>of</strong> view point towards a poetics: ‘an approach to<br />

acts <strong>of</strong> dance- and performance-making that proposes the possibilities<br />

<strong>of</strong> a radical coherence – how things might hold together<br />

without falling into conventional forms and flows. It considers thinking,<br />

dancing bodies [...] as forms <strong>of</strong> such radical coherence – that<br />

is, as a means <strong>of</strong> proposing conditions for the emergence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unforeseen, the unimagined, and the remarkable.’ (Allsopp, 2015: 24)<br />

The work <strong>of</strong> SODA thought <strong>of</strong> as a sense <strong>of</strong> potential ‘coherence’<br />

based not in argument but in imaginative possibility.<br />

LOCATIONS<br />

Mime Centrum Library<br />

(2008)<br />

Photo © Ric Allsopp<br />

The character <strong>of</strong> the SODA programme - like any intensive, practice-based<br />

course - takes in part its direction and dynamic from<br />

the physical environments that it interacts with. The pilot phase<br />

starting in October 2007 was based around a large table at the<br />

Mime Centre in Schoenhauser Allee and had to make use <strong>of</strong><br />

studio-space in various locations including the HfS studios in Immanuelkirchstrasse,<br />

and the Malersaal <strong>of</strong> the Komische Oper at<br />

Zehdenicker Strasse. Whilst the Mime Centre possessed a comprehensive<br />

video documentation <strong>of</strong> contemporary performance<br />

and dance in Berlin which provided an appropriate research<br />

resource for the programme, the dispersed feel <strong>of</strong> the pilot phase<br />

underlined the educational need for a more permanent location<br />

from which to develop the SODA programme.<br />

18

The move to the Alte Kantine at Uferhallen (2010) whilst the 1920s<br />

buildings <strong>of</strong> the old central workshops <strong>of</strong> the BVG (Berlin Public<br />

Transport system) that were to become Uferstudios were being<br />

refurbished, provided a more focussed location for the programme<br />

with a dividable studio space, an <strong>of</strong>fice / kitchen and a small garden<br />

that enabled a sense <strong>of</strong> a ‘home-ground’ for the new SODA<br />

(2010–2012) group starting in April 2010. The <strong>of</strong>ficial move to the<br />

newly refurbished Uferstudios housing the three HZT programmes,<br />

as well as Tanzfabrik Berlin, ada Studio, Tanzbüro and the independent<br />

sector, was in October 2010 with the SODA programme<br />

moving into shared studio space from April 2011 with the start <strong>of</strong><br />

the new SODA (2011–2013) group.<br />

1. Since its initial pilot phase which ran between<br />

October 2007 and July 2009, <strong>MA</strong> SODA has been regulated<br />

by the UdK, and the <strong>MA</strong> Choreography (<strong>MA</strong>C)<br />

which started in October 2008, regulated by the HfS.<br />

2. The SODA Working Group consisted <strong>of</strong> Rhys Martin,<br />

Eva-Maria Hoerster (Managing Director, HZT, 2006–<br />

2013), André Thériault (Artistic Director, Tanz im August)<br />

and Sabine Trautwein, HZT Administrator, 2006– present)<br />

with the choreographer Thomas Lehmen as consultant.<br />

3. The Symposium included live and video contributions<br />

from: Gabriele Brandstetter, Carol Brown, Rosemary<br />

Butcher, Alice Chauchat, Franz-Anton Cramer (reportage),<br />

Scott deLahunta, Jeroen Fabius, Joao Fiadeiro,<br />

Susan Leigh Foster, Deborah Hay, Claudia Henne (moderator),<br />

Pirkko Husemann (moderator), Myriam van<br />

Imschoot, Mette Ingvartsen, Benoit Lachambre,<br />

Hans-Thies Lehmann, Thomas Lehmen, [whose studio<br />

the symposium took place in] Xavier LeRoy, Susanne<br />

Linke, Mark Tompkins, and Georg Weinand.<br />

4. The IAB was formed by William Forsythe (choreographer),<br />

Scott deLahunta (dance researcher),<br />

Gabriele Klein (Hamburg University), Ric Allsopp<br />

(MMU) Marijke Hoogenboom (AHK) joining in July<br />

2009, and Anita Donaldson (HKAPA).<br />

5. The Fachkommission consisted <strong>of</strong> Rhys Martin<br />

(UdK), Helge Musial (HfS) (substitute: Ingo<br />

Reulecke), Thilo Wittenbecher & Martin Nachbar<br />

(Tanz RaumBerlin), Gabriele Brandstetter (Free<br />

University, Berlin) (substitute: Mieke Matzke),<br />

and Eva-Maria Hoerster (Managing Director, HZT).<br />

6. See www.hzt-berlin.de<br />

7. A term drawing on Frederik Jameson’s notion <strong>of</strong> a<br />

‘political unconscious’ (1981) and explored by Sergej<br />

Pristaš for his 2012 workshop Helsinki – [see Networks].<br />

19

20

PROGRAMME<br />

Developing from the initial pilot phase (2007–2009) the core programme<br />

structure has provided a flexible framework within which<br />

SODA students and staff have explored the tensions, trajectories<br />

and directions that SODA has taken within the institutional and<br />

educational frameworks that it has had to operate within or find<br />

ways <strong>of</strong> accommodating. SODA in many respects tracks the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> the dance, performance and art worlds and reflects the<br />

more recent impact <strong>of</strong> social media. This includes not only the<br />

various ‘turns’ since the 1990s in the field <strong>of</strong> dance and performance<br />

- linguistic, conceptual, digital, educational, affective, sensory<br />

and so forth; but also (as primarily an international programme)<br />

the experiential, educational and artistic backgrounds<br />

and assumptions <strong>of</strong> the staff, students, visiting artists and mentors<br />

(see Lists) who have shaped the broader directions and ethos<br />

<strong>of</strong> SODA. As Sabine Huschka indicated in the 2006 Symposium<br />

‘the choice <strong>of</strong> teachers and their respective pr<strong>of</strong>iles would determine<br />

largely the contents <strong>of</strong> the education’ (Cramer, 2006:24)<br />

As things change and transform over time, so then do attitudes<br />

and approaches to the core terms <strong>of</strong> the programme – solo, dance,<br />

and authorship. If the title (in 2006) presented a potential problem<br />

to the artists and theorists who attended the Symposium,<br />

then the shift <strong>of</strong> approach to the title not as a problem but as a<br />

problematic through the experience <strong>of</strong> the pilot programme<br />

(2007–2009) became not only a memorable and useful acronym,<br />

but also a useful and productive point <strong>of</strong> discussion and disagreement<br />

in both practical and conceptual modes, a catalyst for positioning<br />

and integrating both practical and theoretical approaches<br />

to making art work. This would confirm a sense (in both educational<br />

and artistic environments) that how we think <strong>of</strong> arts practice<br />

and how we receive arts practice has been contested since<br />

antiquity as a source <strong>of</strong> both pleasure, disagreement, censorship<br />

and emancipation.<br />

Uferstudios Backgrounds (2011) Photo © Sven Hagolani<br />

21

The development <strong>of</strong> the initial educational framework for SODA<br />

(2010–2012) that incorporated the experience <strong>of</strong> both the 2006<br />

Symposium and the two-year pilot phase, produced a programme<br />

structure that has remained substantially in place with few alterations<br />

over eight annual intakes <strong>of</strong> students including the most<br />

recent SODA intake (2017–19).<br />

STUDENT HANDBOOK EXTRACTS (2010–2017)<br />

What is ‘solo / dance / authorship’?<br />

As an <strong>MA</strong> program that proposes as its basis an open, interrogative<br />

field <strong>of</strong> enquiry, rather than a fixed set <strong>of</strong> references, the terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> its enquiry - ‘solo / dance / authorship’ - are contained in the<br />

program’s title. As a set <strong>of</strong> references ‘solo dance authorship’<br />

might conventionally be understood as the authoring <strong>of</strong> solo<br />

dance - a form or genre which points to an established history<br />

and tradition <strong>of</strong> dance performance. But in the context <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

and emergent practice, the three terms can be additionally<br />

or equally understood as a nexus <strong>of</strong> unstable and contested<br />

meanings. Together they suggest a mode <strong>of</strong> enquiry into embodied<br />

compositional practice that separates the individual terms –<br />

solo / dance / authorship – and their possible relationships, a<br />

territory signified by the slash that indicates both difference and<br />

interdependency.<br />

The terms can be read as inclusive <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> associations:<br />

‘solo’ as: unaccompanied, independent, solitary, single, individual,<br />

alone, virtuosic; ‘dance’ as: movement, gesture, motion; ‘authorship’<br />

as authority, authenticity, control, origination. They can also<br />

be read for what they might exclude or veil: collaboration, participation,<br />

co-operation, everyday movement, anonymity, openness,<br />

informality, and so on. In the context <strong>of</strong> <strong>MA</strong> SODA ‘solo / dance /<br />

authorship’ is proposed as a field <strong>of</strong> enquiry that sets up conditions<br />

for embodied and conceptual engagements from which<br />

contemporary compositional practices can emerge and which<br />

forms a platform for research, exploration and production.<br />

22

In this sense ‘solo / dance / authorship’ forms a poetics: a means<br />

<strong>of</strong> making; a compositional approach to contemporary practice. It<br />

questions the terms <strong>of</strong> its own constitution and in doing so opens<br />

potential and generative areas <strong>of</strong> enquiry. The <strong>MA</strong> SODA does not<br />

therefore propose a restricted approach to solo dance making, but<br />

sets up the conditions that allow students to identify and develop<br />

for themselves and with others their compositional and embodied<br />

practice and its contexts. ‘<strong>Solo</strong> / dance / authorship’ as a mode <strong>of</strong><br />

enquiry does not seek to establish a definition <strong>of</strong> its terms but proposes<br />

an increasing understanding <strong>of</strong> the range <strong>of</strong> its possible<br />

manifestations, contexts and applications.<br />

What is the approach to learning?<br />

The two-year <strong>MA</strong> SODA course combines a taught program with<br />

individual performance-making and independent research, tutorial<br />

and mentoring support. Emphasis throughout is placed on<br />

individual motivation and approaches to learning which underpin<br />

the student’s ability to:<br />

• articulate their practice to themselves, to their peers<br />

and to a public - through presentations, performances,<br />

and the sharing <strong>of</strong> processes; through the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> a Workbook - a document that maps the progress<br />

and process <strong>of</strong> individual performance making –<br />

and through critical framing statements and other<br />

modes <strong>of</strong> verbal presentation and writing that contextualize,<br />

extend and inform their work;<br />

• develop practice-based and intellectual research<br />

skills – through engagement in seminars, critiques,<br />

lectures, and intensive workshops lead by choreographers,<br />

performance art-makers, media-artists, theorists<br />

and creative writers;<br />

• identify specific learning needs in order to develop<br />

their work and understand the contexts <strong>of</strong> its production<br />

and dissemination.<br />

23

CORE APPROACHES<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA focuses on a number <strong>of</strong> core approaches that support<br />

and develop each student’s individual trajectory through the<br />

course. Independent work and the development <strong>of</strong> the student’s<br />

own reflective practice is the main focus and point <strong>of</strong> reference<br />

throughout the course.<br />

• Contemporary Arts Practice: A key proposition <strong>of</strong> the studycourse<br />

is that students are engaged with dance and body-based<br />

performance practices that are concerned with current and<br />

emergent cultural, artistic and aesthetic circumstances and<br />

contexts, and the reciprocal impact that such contexts and practice<br />

have on each other in terms <strong>of</strong> form, process and reception.<br />

The contemporary in this sense is an engagement with and<br />

reflection on what is happening now. <strong>MA</strong> SODA suggests that<br />

contemporary arts practice can usefully and productively be<br />

seen through the lens <strong>of</strong> ‘solo / dance / authorship’ and composition<br />

both in historical readings <strong>of</strong> these terms and as focus<br />

for research.<br />

24

Sonja Pregrad (2011) Wall Writings in Studio 8 Photo © Ric Allsopp<br />

• Theory: The approach to theory is designed to ensure that the<br />

theoretical issues emerging within an individual student’s practice<br />

can be located in relation to current arts discourses. It is<br />

concerned both with the methodological implications <strong>of</strong> theoretical<br />

enquiry by practitioners as well as with specific bodies <strong>of</strong><br />

theory. It addresses the possibilities and limitations <strong>of</strong> shared<br />

theoretical discourse across subject fields. Linked to this it poses<br />

questions about the relation <strong>of</strong> subject-specific fields <strong>of</strong> enquiry<br />

to contemporary meta-discourses.<br />

• Practices / Making New Work: <strong>MA</strong> SODA guides and enables the<br />

student to work towards the thinking and making <strong>of</strong> a substantial<br />

practical work (or set <strong>of</strong> works) <strong>of</strong> their own devising, designed<br />

to define their own position within their field <strong>of</strong> practice by the<br />

end <strong>of</strong> the study course. This is achieved through a series <strong>of</strong><br />

shorter formal, informal and / or intensive engagements with the<br />

methods, processes and contexts <strong>of</strong> making and thinking about<br />

work. Small performance ‘studies’ are planned, encouraging the<br />

student to test ideas, for an audience <strong>of</strong> peers, during their<br />

development, as part <strong>of</strong> the process towards a resolved work.<br />

25

• Contexts: A ‘given’ <strong>of</strong> the <strong>MA</strong> SODA study course is that arts<br />

practices do not take place outside <strong>of</strong> a set <strong>of</strong> contexts – cultural,<br />

political, environmental, social, aesthetic, historical, personal –<br />

and that a key relationship between making, thinking and doing<br />

is not only a formal one, but a contextual one. A central question<br />

then is always ‘for whom?’ What are the circumstances and imperatives<br />

<strong>of</strong> making work, <strong>of</strong> engaging with a particular poetic or<br />

compositional approach?<br />

• Composition: The term ‘composition’ is used – as opposed to<br />

‘choreography’ or ‘dramaturgy’ – to suggest that much contemporary<br />

arts practice employs a very plural and diverse range <strong>of</strong><br />

strategies and tactics for making relations between the material<br />

and immaterial ‘stuff’ <strong>of</strong> performance; and draws increasingly on<br />

cross-disciplinary and cross-media methods, approaches and<br />

discourses. The current (at least Western) performance arts<br />

context <strong>of</strong> ‘making work’ could indeed be said to be post-disciplinary<br />

and inter-medial.<br />

• Diagnostics: Diagnostics is designed to underpin an approach<br />

to <strong>MA</strong> level study that works for a productive relationship<br />

between practice and theory through systematic self- and peerevaluation,<br />

and an engagement with a range <strong>of</strong> methodologies<br />

for learning, practice and research. It is also designed to mobilize<br />

the student group as a cross-disciplinary resource for all<br />

students. The diagnostic part <strong>of</strong> the first Semester takes as its<br />

main focus the student’s own analytical account <strong>of</strong> their<br />

engagement with performance practices and associated discourses.<br />

Each student will describe and present their past work,<br />

present position and their aspirations. They will reflect on their<br />

working and learning practices, and consider and respond to<br />

feedback from peers and tutors. They will <strong>of</strong>fer considered feedback<br />

to peers. As an integral part <strong>of</strong> the learning process, each<br />

student makes a presentation to the group and participates in<br />

formative peer-assessment as part <strong>of</strong> their engagement with the<br />

work <strong>of</strong> peers. Diagnostics uses critique and feedback as a part<br />

<strong>of</strong> its methodology.<br />

26

• Critiques & Feedback: Group critiques are meetings in which<br />

participants discuss each other’s work or research. These meetings<br />

take place on a regular basis throughout the first two semesters.<br />

Students present their work for a group discussion at least<br />

once a semester. All students are expected to take part in all<br />

group critiques; since the critiques are about looking at work<br />

and thinking through artistic questions together, their success<br />

as a stimulating and supporting course element depends on<br />

everyone’s commitment to participate and make them productive.<br />

In presenting individual work to the group, the group critique<br />

functions as a forum for critical reflection on individual<br />

practice, and allows students to test their work, intentions and<br />

way <strong>of</strong> looking and contextualizing on an audience <strong>of</strong> peers.<br />

Being confronted with the way others read individual work or<br />

comment on the way it is framed may help in making artistic decisions<br />

or opening up new perspectives. Vice versa, discussing<br />

the work <strong>of</strong> other students is an exercise in reading art / performance<br />

works, in thinking out loud and testing and comparing different<br />

perspectives.<br />

• Modes <strong>of</strong> Writing: The exploration <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> modalities <strong>of</strong><br />

writing in relation to performance making takes as its assumption<br />

that language (as both speech and writing) is not distinct or<br />

separated from dance and body-based performance forms, but is<br />

an integral part <strong>of</strong> any form <strong>of</strong> embodied thinking and making.<br />

Writing and orality are therefore approached as a means <strong>of</strong> opening<br />

up our understandings, interpretations and engagements<br />

with performance thinking and making. Modes <strong>of</strong> writing would<br />

include writing as, for, or with, performance; its implications for<br />

compositional structures and for forms <strong>of</strong> writing in relation to<br />

performance; critical and discursive writings; descriptive writings<br />

and so on.<br />

• Textual Practice(s): The exploration and engagement with structures<br />

<strong>of</strong> language (that is, forms <strong>of</strong> textual practice) in relation to<br />

writing, provides a bridge between body-based and dance practices<br />

and their articulation and exploration by other means. This<br />

might include critical readings and evaluations <strong>of</strong> the work <strong>of</strong><br />

contemporary practitioners in both script- and art-based writings;<br />

the exploration <strong>of</strong> procedures, textures, assemblages, compositional<br />

structures, forms, scripted performance behaviors, and<br />

editorial approaches leading to sustainable writing / textual<br />

practice(s); live, visual, sonic, spatial and digital treatments <strong>of</strong><br />

writing in its relation to performance.<br />

27

• Research for Artists: Research for artists proposes that thinking<br />

and making in the field <strong>of</strong> performance requires approaches and<br />

methods beyond academic, analytic and objective methods, and<br />

that individual artistic practice <strong>of</strong>ten involves an eclectic range<br />

<strong>of</strong> generative knowledges. Some (conventional) methodologies<br />

are taught or demonstrated. Others are examined critically, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

using a case-study approach that reviews methodology from<br />

the point <strong>of</strong> view <strong>of</strong> both intention (or framework <strong>of</strong> assumptions)<br />

and <strong>of</strong> outcome. The range <strong>of</strong> methodologies examined<br />

will include: postgraduate level study skills; methodologies for<br />

academic research; practice as research / practice as learning;<br />

research requirements <strong>of</strong> practical projects; documentation;<br />

collaborative work.<br />

<br />

Yaron Maïm (2017) from Material for a <strong>Solo</strong> VIII - XCVZ, eXit the Cage <strong>of</strong> the Virtual Zoo Photo © Ric Allsopp<br />

28

COURSE STRUCTURE<br />

The <strong>MA</strong> uses both formal and informal structures as the basis for<br />

its enquiry. As well as a modular format, these include participation<br />

in local and international networks enabling exchange research<br />

and dialogue; opportunities for students to curate single<br />

workshops, seminars, and lectures with invited artists, and visiting<br />

exhibitions, performances and other relevant cultural and<br />

educational activities in Berlin and elsewhere.<br />

Semester 1: Questions <strong>of</strong> Practice 1: Diagnostics /<br />

Writing Practices / Making New Work<br />

takes three key approaches to making and thinking practice:<br />

diagnostics – the ability to share processes <strong>of</strong> making work;<br />

writing & research for artists – the ability to place practice in relation<br />

to language and identify and utilize appropriate research<br />

methods with which to develop practice; making new work - the<br />

ability to identify and develop new approaches to making and<br />

thinking practice.<br />

Negotiating <strong>Solo</strong> / <strong>Dance</strong> / <strong>Authorship</strong>: Lecture / Seminar Series 1<br />

explores critical, contextual, and theoretical understandings <strong>of</strong><br />

key terms <strong>of</strong> the course. The first series <strong>of</strong> lecture / seminars addresses<br />

the contexts, implications and relationships <strong>of</strong> the key<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> the <strong>MA</strong> - ‘solo’, ‘dance’ and ‘authorship’ - in relation to<br />

contemporary arts practice and theory.<br />

Semester 2: Questions <strong>of</strong> Practice 2:<br />

Compositional Strategies & Tactics<br />

examines the work process <strong>of</strong> composition as research through<br />

artistic practice by exploring and testing various compositional<br />

strategies, tactics and work processes and analyzing the aesthetic<br />

and cultural contexts that make them possible and support them.<br />

Compositional Practices & Contexts: Lecture / Seminar Series 2<br />

addresses questions <strong>of</strong> thinking and making contemporary practice<br />

in relation to the histories and strategies <strong>of</strong> 20 th and 21 st century<br />

compositional practice and contexts.<br />

Semester 3: Independent & Collaborative Research<br />

following an initial independent research proposal at the end <strong>of</strong><br />

Semester 2, you embark on a sustained program <strong>of</strong> individual<br />

research designed and structured in discussion with tutors.<br />

29

Semester 4: Final SODA Project & Documentation<br />

The Final SODA Project involves the production <strong>of</strong> a performance<br />

work that engages with solo and/or collaborative dance authorship,<br />

that can be performed or presented in the public arena, and<br />

meets conceptual, aesthetic and production criteria that apply in<br />

wider pr<strong>of</strong>essional arts communities and / or the cultural location<br />

for which the work is designed. Students prepare an initial proposal<br />

for their project at the end <strong>of</strong> Semester 3 which is negotiated<br />

and finalized with tutors / mentors toward the beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

final Semester 4. The project is shown publicly as a part <strong>of</strong> a negotiated<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA performance platform. This final module also provides<br />

an opportunity for students to engage in a detailed documentation<br />

and reflection on their work. The documentation takes<br />

the form <strong>of</strong> a substantial critical framing statement that positions<br />

the work in relation to the student’s own experience and to wider<br />

cultural and aesthetic questions and conditions, and a final workbook<br />

devoted to the compositional, conceptual and contextual<br />

processes <strong>of</strong> the project.<br />

Igor Koruga (2012) from Come Quickly, My Happiness is at Stake Photo © Igor Koruga<br />

30

WORKBOOKS & FRAMING STATEMENTS<br />

Modes <strong>of</strong> written work and documentation are integral to the development<br />

<strong>of</strong> your practice within <strong>MA</strong> SODA. These take the form<br />

<strong>of</strong> workbooks (process documentation) and written papers (essays<br />

and written framing statements).<br />

Workbooks<br />

Writing as a way <strong>of</strong> engaging research through practice plays a<br />

vital role in <strong>MA</strong> SODA from the outset. The emphasis is on developing<br />

an ongoing practice <strong>of</strong> writing as a tool, and its employment<br />

in the processes <strong>of</strong> research and artistic exploration. The Workbook<br />

is to be thought <strong>of</strong> as integral and integrated space for writing<br />

in the context <strong>of</strong> the <strong>MA</strong>.<br />

The Workbook is a term (and material form) that has a long history<br />

in fine art and choreographic practice – from Leonardo to Marcel<br />

Duchamp to Tracey Emin; from Raoul Auger Feuillet to Yvonne<br />

Rainer to William Forsythe. Within the Art School tradition, the<br />

Workbook is presented alongside the final artwork as a commentary<br />

on the process <strong>of</strong> making. In the context <strong>of</strong> <strong>MA</strong> SODA the<br />

Workbook is a selection or collection <strong>of</strong> different writings, notes,<br />

texts, graphic materials, sound or video files gathered together<br />

and displayed in a book, a folder, and/or stored on, screened<br />

through, digital media.<br />

The Workbook is imagined as a cross-media working space whose<br />

contents are not expected to have coherence as a single piece <strong>of</strong><br />

writing. They should have instead the coherence <strong>of</strong> a learning process<br />

that relates to the experience and processes <strong>of</strong> <strong>MA</strong> SODA.<br />

The overall form <strong>of</strong> the Workbook is not prescriptive. It is an open<br />

work whose form and content document and extend the practice-led<br />

research <strong>of</strong> the individual student. It is a document that<br />

assembles the processes <strong>of</strong> making and research, and whose<br />

multiple contents provides a descriptive, critical and interrogative<br />

commentary for the individual’s practice.<br />

The Workbook maps the research trajectories <strong>of</strong> its maker using<br />

different modes <strong>of</strong> documentation, writing and graphic representation.<br />

It enables the reader / user to explore the way individual<br />

students might effectively represent their own processes<br />

<strong>of</strong> inquiry, their production processes, and those <strong>of</strong> other artists.<br />

The process <strong>of</strong> making the Workbook is not in any essential sense<br />

separate from the processes <strong>of</strong> making art / performance work –<br />

both provide a means <strong>of</strong> questioning, exploring, and reflecting on<br />

the act <strong>of</strong> composition, <strong>of</strong> bringing material into dialogue with a<br />

spectator, a reader, an audience.<br />

31

Marcio Carvalho (2011)<br />

from Workbook 401<br />

Photos © Marcio Carvahlo<br />

32

The more complex the Workbook becomes, the more it needs (in<br />

the context <strong>of</strong> <strong>MA</strong> SODA) a means <strong>of</strong> navigation for the reader<br />

which might include: contents pages, indexes, introductions,<br />

sections, pagination, framing statements, glossaries, acknowledgements,<br />

colophons – the paratextual paraphernalia <strong>of</strong> the<br />

making and research processes. Like any writing the Workbook<br />

is a formalization <strong>of</strong> memory – both prospective and retrospective<br />

– and care should always be taken in selection, commentary<br />

and presentation.<br />

The Workbook is a key formal element <strong>of</strong> assessment throughout<br />

the <strong>MA</strong> SODA course. The objectives <strong>of</strong> the Workbook include<br />

self-reflexive written accounts <strong>of</strong> performance making; the production<br />

<strong>of</strong> performance documentation; and facility with writing<br />

appropriate to interpretation and explanation. In terms <strong>of</strong> assessment<br />

the Workbook will provide evidence <strong>of</strong> the making processes<br />

and the individual student’s ability to articulate their own practice<br />

in critical and reflective modes.<br />

Framing Statements<br />

The written Framing Statement which forms an integral part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Final Project assessment is a concisely articulated and considered<br />

written statement that informs a reader <strong>of</strong> the contexts,<br />

research questions and processes that inform the work; provides<br />

an overview <strong>of</strong> the intentions, aims and positioning <strong>of</strong> the work;<br />

and gives the reader a frame <strong>of</strong> reference - descriptive, discursive,<br />

critical, theoretical - through which to engage with the work.<br />

The Framing Statement should link or refer to the aims and intentions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Final Project Proposal.<br />

As a part <strong>of</strong> the creative process <strong>of</strong> <strong>MA</strong> SODA, the Framing Statements<br />

(both Verbal and Written) and the Workbook should find<br />

their own forms appropriate to the individual students’ learning<br />

process and the development <strong>of</strong> an articulated, critical and reflective<br />

practice. In the Final Project module (401) it is suggested that<br />

the Framing Statement might take the form <strong>of</strong> a performance program<br />

or exhibition catalogue as appropriate.<br />

33

EXTRACTS I<br />

The contributions that constitute the three sections <strong>of</strong> Extracts –<br />

from student workbooks, from alumni and current students, and<br />

from staff – are in response to an invitation send out in July<br />

2017 to all the SODA graduates and staff from (2007–2016). It<br />

invited some help, direction and information with some or all, <strong>of</strong><br />

the following:<br />

• a short thought (max. 150 words) that distils the ‘essence’ <strong>of</strong> your<br />

SODA educational / artistic / conceptual / or social experience<br />

• what hyperlinks to your own current (and past) work can you <strong>of</strong>fer?<br />

• what imaginative / discursive / poetic / educational / transdisciplinary<br />

/ philosophical / artistic spaces have been opened-up for you<br />

by SODA over the last decade?<br />

• what examples / brief extracts / images can you <strong>of</strong>fer from SODA<br />

workbooks, lecture series, workshops, performance that have<br />

made an impact on you, or remain in memory as distinctive or<br />

exemplary <strong>of</strong> the SODA programme?<br />

Given the format and timescale <strong>of</strong> the printed book, it has only<br />

been possible to include a selection <strong>of</strong> the ideas, images and<br />

extracts that have been contributed or that have emerged during<br />

its compilation. The digital version (www.issuu.com/hztberlin)<br />

enables hyperlinks to SODA student and staff work listed in the<br />

Addenda or elsewhere in the book.<br />

Uferstudios Backgrounds (2011) Photo © Sven Hagolani<br />

35

Céline Cartillier<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA 2012–2014<br />

Céline Cartillier (2013) from Pathfinder’s Rhapsody Photo © Marion Borriss<br />

Rhapsody for Pathfinders is a collection <strong>of</strong> texts which trace the r e-<br />

search and creation process I have been undertaking and developing<br />

mostly during the third semester <strong>of</strong> the SODA program. This documentation<br />

presents the different aspects and steps <strong>of</strong> the work I have<br />

been doing in this period and the materials that enriched the performance<br />

practice. There are writings, readings, quotes, notes inspired<br />

by books and movies. There are scores and performance directives<br />

directly connected to a physical and vocal training. There are texts<br />

and poems that I wrote on the perspective <strong>of</strong> the performance. Some<br />

<strong>of</strong> them don't appear in the performance. But they are like the companions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the whole process.<br />

Rhapsody for Pathfinders is also the title I choose to give to the research<br />

presentation <strong>of</strong> the third semester.<br />

I entered in the SODA program with intentions for a project I called for<br />

an ideal theatre. Since April 2012 I dedicated my work to search for<br />

relations between ideal and representation in the frame <strong>of</strong> a performance<br />

practice.<br />

I took this research semester as an opportunity to reconsider what<br />

the components <strong>of</strong> an ideal theatre are to me. What do I mean by ideal?<br />

What do I mean by theatre? What do I mean by an ideal theatre? I<br />

went back to the original meaning <strong>of</strong> those words. The seat <strong>of</strong> an ideal<br />

theatre is obviously the idea. An ideal theatre is consequently a theatre<br />

that gives precedence to the mind and the imagination. Originally<br />

theatre comes from the ancient greek verb théaô which means ‘to<br />

see’. In the third term <strong>of</strong> the research I deeply measured how all my<br />

inquiries for an ideal theatre embedded a phenomenological dimension,<br />

a phenomenology <strong>of</strong> the gaze. An ideal theatre, a place to see<br />

from the imagination.<br />

From Rhapsody for Pathfinders – a workbook (April–July 2013)<br />

36

dearest one,<br />

things happen behind your back.<br />

a lot <strong>of</strong> things. happen.<br />

words are said. eyes are riveted.<br />

some words are bitter, some eyes are warm.<br />

there is a zone in your neck, precisely –<br />

a crevasse, called the door <strong>of</strong> the wind.<br />

from there, drafts enter.<br />

from there, you can hear the voices haunting the icy wind.<br />

from there, you can feel the gaze penetrate you.<br />

there are parts <strong>of</strong> your body that you cannot see.<br />

your back is one <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

you are ahead <strong>of</strong> it and yet it escapes you.<br />

your back is your missing image.<br />

ô no no not the only one missing....!<br />

one <strong>of</strong> those images that looks back at us,<br />

your back is the invisible stranger that follows you.

Felix Marchand<br />

<strong>MA</strong> SODA 2007–2009<br />

Felix Marchand (2009) from<br />

Awareness Etudes<br />

Photos © Felix Marchand<br />

38

Awareness Etude for 6 performers and an Audience (2009)<br />

Awareness Etude 1 – Bones<br />

Map the pathway <strong>of</strong> the bones in one specific body part (hand, foot, head...). Use the<br />

floor to give you the feedback where you are. The rest <strong>of</strong> the body follows the initiation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mapping. Moments <strong>of</strong> stillness can happen by the consequence <strong>of</strong> the mapping<br />

or by a conscious decision. The generated shape allows two possibilities to continue:<br />

continue mapping the bones; traveling through space in the shape you are in.<br />

Awareness Etude 2 – Skin and Nerve system<br />

Create a movement phrase, which is based on what your body remembers from past<br />